Hills v. Gautreaux Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 15, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hills v. Gautreaux Brief Amici Curiae, 1975. 57d56e36-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/00009808-23a5-437b-8d59-d8420eadd57e/hills-v-gautreaux-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

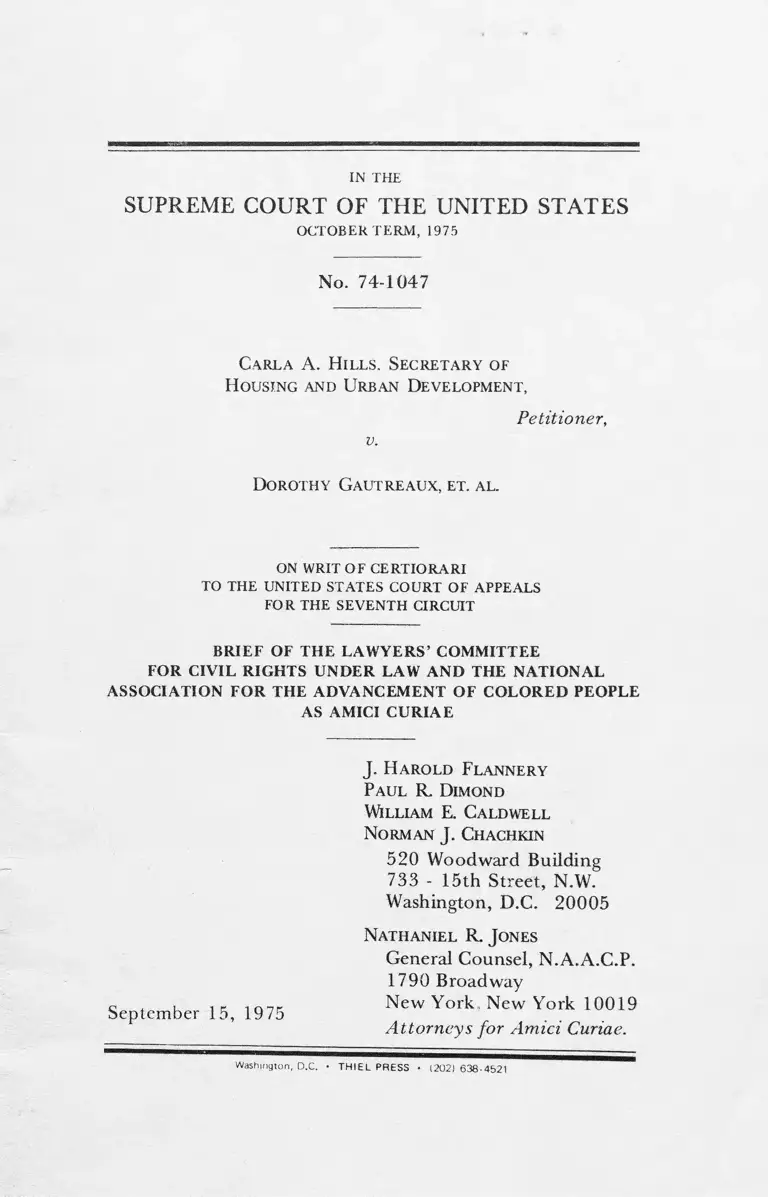

SU PR E M E C O U R T O F T H E U N IT E D S T A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1975

IN THE

No. 74-1047

Carla A. H ills. Secretary of

H ousing and Urban Development,

v.

Petitioner,

Dorothy Gautreaux, et. al.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AND THE NATIONAL

ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

AS AMICI CURIAE

September 15, 1975

J. H arold Flannery

Paul R. Dimond

William E. Caldwell

Norman J . Chachkin

520 Woodward Building

733 - 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Nathaniel R. J ones

General Counsel, N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York New York 10019

A ttorn eys for Am ici Curiae.

Washington, D.C. • THIEL PRESS ■ 12021638-4521

(0

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES............................................................. i

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE .................................... ................1

STATEMENT OF FACTS............................................................. .. . 4

ARGUMENT

Introduction ......................................................................................13

I. The Writ of Certiorari Should Be Dismissed And

Review o f This Matter Postponed Until After

Further Proceedings in the Trial C ou rt.............................. 14

A. Petitioner Does Not Have Standing To Attack

the Judgment of the Court of Appeals on the

Grounds Raised in its Petition and Brief . . . . . . . . 14

B. The Record in This Matter is Insufficient To

Permit Decision of the Constitutional Claim

Raised by Petitioner............................................... 19

II. Should This Court Reach the Merits, the Judgment

Below Should be Affirmed Because It is Consistent

With Milliken v. Bradley ..........................................................25

CONCLUSION................................................................ 27

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Adams v. Richardson, 351 F. Supp. 636 (D.D.C. 1972),

356 F. Supp. 92 (D.D.C.), modified in part and

aff’d, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.D.C. 1973)....................................... 8n

Alabama State Federation of Labor v. McAdory, 325

U.S. 450 (1 9 4 5 ) ............................................... .. ......................... 25

CIO v. McAdory, 325 U.S. 472 (1 9 4 5 )....................................... 25

County Court of Braxton County v. State ex rel.

Dillon, 208 U.S. 192 (1 9 0 8 )..................................................... 18

Diaz v. Patterson, 263 U.S. 399 ( 1 9 2 3 ) ......................... 18

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, 503 F.2d

930 (7th Cir. 1974), cert, granted, 44 L.Ed.2d

448 (1 9 7 5 ).................................................................. 12, 16n, 21

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, 436 F.2d

306 (7th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 992

(1 9 7 1 )............................................................................................... 9n

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, 384 F. Supp.

37 (N.D. 111. 1974), mandamus denied, 411 F.2d

82 (7th Cir. 1975).................................................... .. ................ 9n

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, 342 F. Supp.

827 (N.D. 111. 1972), aff’d sub nom. Gautreaux v.

City of Chicago, 480 F.2d 210 (7th Cir. 1973),

cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1144 (1974)........................................... 9n

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, 304 F. Supp.

736 (N.D. 111. 1969)............................................................... 6, 7n

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, 296 F. Supp.

736 (N.D. 111. 1969)..........................................................................5

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, 265 F. Supp.

582 (N.D. 111. 1967).......................................................................... 5

Gautreaux v. Romney, 448 F.2d 731 (7th Cir. 1971) . . . . ,7, 8

Gautreaux v. Romney, 363 F. Supp. 690 (N.D. 111.

1973). ................................................................................ 11

Gautreaux v. Romney, 332 F. Supp. 366 (N.D. 111.

1971), rev’d 457 F.2d 124 (7th Cir. 1 9 7 2 ) ........... .. 9n

ICC v. Chicago, R.I. & P.R. Co., 218 U.S. 88 (1 9 1 0 ).............. 19

Kelsey v. Weinberger, 498 F.2d 701 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) ........... ,23

Massachusetts v. Mellon, 262 U.S. 447 (1 9 2 3 )............................. ,19

Massachusetts v. Painten, 389 U.S. 560 (1968).............. .. 21n

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1 9 7 4 ) ...............................passim

Parker v. County of Los Angeles, 338 U.S. 327

(1949) .............................................................................................. 25

Penfield Co. v. SEC, 330 U.S. 585 (1947)................................. 19

Rescue Army v. Municipal Court, 331 U.S. 549

(1 9 4 7 ).................................. .......................................................... 25

Shannon v. HUD, 436 F.2d 809 (3d Cir. 1 9 7 0 )......................... 2

Southern Burlington County NAACPv. Township

of Mt. Laurel, 67 N.J. 1 5 7 ,___A.2d___ (1975).......................2

Cases, continued: Page

Cases, continued:

Warth v. Seldin, 45 L„Ed.2d 343 (1975)

Wheeler v. Barrera, 417 U.S. 402 (1974)

14, 15, 18, 19

. . . . 24n, 25

Page

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. § § 1437f(b)(l)-(2). .............................................22n, 23n

42 U.S.C. § § 1439(a)(3)-(4).......................................................... 22n

42 U.S.C. §2000d ................................................. 5n

42 U.S.C. §5301(c)(6 ).................................... .. ........................ .. . 22n

42 U.S.C. §5304(a)(4)(c)(ii)......................... .. .............................. 22n

Other Authorities:

Northeastern Illinois Planning Commission, Moderate and

Low-Income Housing, A Ten Year Estimate of Regional

Needs ( 1 9 7 3 ) ................................ 10n

K. & A. Taeuber, Negroes in Cities (1965)......................................... 3

S. Rep. No. 200, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. (1970)................................ 3

U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, The Federal Civil Rights

Enforcement Effort (1 9 7 4 )................... .....................................3

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1975

No. 74-1047

Ca rla A. H il l s . Sec r eta r y of

H ousing and U rban Dev elo pm en t ,

v.

Petitioner,

D o ro th y G a u tr ea u x , e t . a l .

on writ o f c e r tio r a r i

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AND THE NATIONAL

ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

AS AMICI CURIAE

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE*

The Law yers’ Com m ittee for Civil Rights U nder Law

was organized on June 21, 1963 following a conference

of lawyers called at the White House by the President.

The C om m ittee’s principal mission is to involve private

*Both the Petitioner and the Respondents have consented to

the filing of this brief. Copies of letters from their counsel to

this effect have been filed with the Clerk of this Court pursuant

to Rule 42(2).

i

2

lawyers th roughout the country in the struggle to assure

all citizens o f their civil rights through the legal process,

in particular by affording legal services otherwise unavail

able to Black and o ther m inority Americans pursuing

claims for equal trea tm ent under law. The Law yers’

Com m ittee is a nonprofit, private corporation whose

Board o f Trustees includes th irteen past presidents of the

Am erican Bar Association, three form er A ttorneys G en

eral, and tw o form er Solicitors General.

The N ational Association for the A dvancem ent of

Colored People (NAACP) is a nonprofit m embership

association representing the interests o f approxim ately

500,000 members in 1800 branches throughout the

U nited States. Since 1909, the NAACP has sought

through the courts to establish and p ro tec t the civil rights

of m inority citizens. In this respect, the NAACP has

often appeared before this C ourt as an amicus in cases

involving school desegregation, em ploym ent, voting

rights, ju ry selection, capital punishm ent, and o ther cases

involving fundam ental hum an rights.

The NAACP and the Law yers’ Com m ittee, and their

local com m ittees, affiliates, branches, and volunteer

lawyers, have long been actively engaged in providing

legal representation to those seeking free and nondiscrim-

inatory access to decent housing. Their litigation has

concerned issues similar to those in the instan t case.

See, e.g., Shannon v. HUD, 436 F ,2d 809 (3d Cir. 1970);

Southern Burlington County NAACP v. Township o f Mt.

Laurel, 67 N .J. 157, A .2d (1975). Along w ith

o ther in terested organizations, the Law yers’ Com m ittee

on D ecem ber 9, 1969 subm itted a brief amicus curiae in

the D istrict C ourt in the com panion case to this one. {See

Record [Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority file],

Vol. I, Item No. 50).

3

The experience of amici in these cases has am ply

dem onstrated to us the validity of the tw o central

findings reiterated in num erous academic and official

studies o f housing patterns in the U nited States: first,

tha t racial residential segregation is neither accidental nor

desired by Black Americans, b u t is the p ro d u c t of

discrim ination against them ; and second, th a t govern

m ental policies — including, since 1937, the num erous,

diversified, and om nipresent activities in the housing

m arket o f the Petitioner HUD and its predecessor

agencies—are responsible in significant measure for the

exacerbation and perpetuation o f such racial discrim ina

tion and resulting racial residential segregation. E.g.,

K. & A. Taeuber, Negroes in Cities (1965); II U.S.

Com m ’n on Civil Rights, The Federal Civil Rights

Enforcem ent E ffort (1974); c f Statem ent o f HUD

Secretary Rom ney, S. Rep. No. 200, 92d Cong., 2d Sess.

121 et seq. (1970). Indeed, the segregative effects o f the

federal governm ent’s policies have been the m ore severe

because their form ulation and im plem entation coincided

with the period o f greatest expansion of housing and of

suburban developm ent in the U nited States, and because

such policies served as a m odel for racially discrim inatory

actions of o ther governmental agencies and private

parties.1

In the instan t case, Petitioner seeks to have this C ourt

confine, w ithin the boundary lines o f individual political

subdivisions, the equitable powers o f federal courts to *

* See Record (Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority file),

Vol. II, Item No. 76 (Stipulation dated June 29, 1968), Exhibit

3: “The Chicago Housing Authority, at the time of its organization,

adopted a policy that had been established by the [federal] PWA

Housing Division — namely, that the Authority would not permit

a housing project to change the racial make-up of the neighborhood

in which it was located . . . .”

4

rem edy governm ental discrim ination which was never so

lim ited in execution or effect. A ny absolute lim itation of

this sort w ould cripple our efforts, and those of others, to

open to m inority Americans housing opportunities which

until now have been closed to them because of their race.

The NAACP and the Law yers’ C om m ittee accordingly

have a vital in terest in the disposition of this m atter.

Because we believe th a t Petitioner has m isapprehended

the effect o f the ruling below and because, in any event,

the posture of this case is unsuited for disposition of the

u ltim ate rem edial questions before this C ourt, we subm it

this Brief as friends of the C ourt urging tha t the w rit of

certiorari heretofore granted be dismissed for lack of

standing or as having been im providently granted.2

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The parties have set forth the intricate procedural

h istory and related factual setting o f this m atter in their

respective briefs. For the purposes o f this amici sub

mission, however, we summarize the salient facts below.

This case (and the com panion suit w ith which it was

consolidated in 1971) was institu ted in 1966. Plaintiffs

are Negro residents of, or applicants for admission to ,

public housing constructed or operated by the Chicago

Housing A uthority [hereinafter “CH A ”] and approved

and financed by the U nited States through Petitioner

9

As we suggest infra pp. 25-27, we believe that Respondents

should prevail before this Court should the matter be considered

on its merits, because the remand ordered by the Court of Appeals

is not in any way inconsistent with nor does it foreclose applica

tion of the substantive ruling in Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S.

717 (1974), as Petitioner seems to believe. To the contrary, the

Seventh Circuit’s remand specifically requires District Court con

sideration of Milliken.

5

HUD and its predecessors. Both suits a ttacked the local

and federal defendants’ historic policies and practices of

locating m ost public housing in the C ity of Chicago

w ithin areas of existing m inority concen tration , so as to

m aintain and aggravate racial residential segregation.

Plaintiffs seek the opportun ity to reside in public housing

which has n o t been deliberately restric ted to predom i

nantly Black residential areas.3

Following extensive discovery in the action against the

CHA (proceedings in the HUD case having been stayed),

the D istrict C ourt granted sum m ary judgm ent in favor of

the plaintiffs. The C ourt found th a t the four Chicago

housing projects located in w hite neighborhoods had

quotas to lim it the admission o f Negro tenants, and th a t

CHA used a m ethod of site selection clearance which

resulted in the veto of “ substantial num bers o f sites [in

white neighborhoods] on racial grounds.”4 The D istrict

Court rejected the possible rem edy o f term inating federal

financial assistance to the CHA5 because “ it is n o t clear

w hether even a tem porary denial o f federal funds w ould

no t im pede the developm ent of public housing and thus

damage the very persons this suit was b rought to

p ro tec t.” 6 Instead, the C ourt d irected the parties to

propose appropriate injunctive relief constitu ting “a

com prehensive plan to p roh ib it the fu ture use and to

rem edy the past effects of CHA’s unconstitu tional site

selection and tenan t assignment procedures.” 7

3

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, 265 F. Supp. 582,

583 (N.D. 111. 1967) (denying motion to dismiss).

4Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority,296 F. Supp. 907,

909, 913 (N.D. 111. 1969)

5See 42 U.S.C. §2000d (Section 601, Civil Rights Act of

1964).

6 296 F. Supp., at 915.

7Id., at 914.

6

On Ju ly 1, 1969, the D istrict C ourt entered its initial

remedial order against CHA. The decree established a new

tenan t assignment procedure for CHA projects as well as

guidelines for location o f fu ture public housing. The City

of Chicago was divided in to a “ Lim ited Public Housing

A rea” and a “ General Public Housing A rea” based upon

existing racial residential concentrations; CHA was en

jo ined from locating any additional public housing in the

(more heavily Black) “ Lim ited Public Housing A rea” of

the city. Thereafter, at least 75% of all new public

housing was to be located w ithin the “ General Public

Housing A rea” o f the c ity .8 CHA was fu rther authorized

to locate one-third of this am ount (25% of all new units

after the initial 700):

. . . in the General Public Housing A rea of the

C ounty o f Cook in the S tate of Illinois, outside of

the City o f Chicago, provided th a t (w hether or no t

constructed by CHA) the same are m ade available

for occupancy by CHA to, and are occupied by,

residents of the C ity o f Chicago who have applied

for housing to CHA. . . .9

8 Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, 304 F. Supp. 736,

738-40 (N.D. 111. 1969). At the time the 1969 order was entered,

local housing authorities submitted estimates of public housing

need to HUD and received “reservations” from the agency for

specific numbers of public housing units, prior to undertaking the

processes of site location and design; 700 units of a prior reser

vation to CHA remained. The District Court’s order thus required

that the balance of that reservation be located within predom

inantly white areas of Chicago, and that three-quarters of all

public housing units built pursuant to future reservations from

HUD be located in predominantly white areas. Cf. p. 10, infra.

In 1969 CHA received a reservation for 1500 additional units

from HUD, after making a request for 5000 units. Record,

Transcript o f Proceedings, September 28, 1972, at 188.

9Id,., at 739. To locate public housing for Chicago residents

outside the city limits under the order, CHA not only had to enter

[ fo o tn o te con tinued]

7

The order also contained provisions describing the type

o f public housing units CHA could build (to avoid undue

concentration o f public housing in any location), p rohib i

ting CHA from using the pre-clearance site selection p ro

cedure which had in the past resulted in discrim inatory

location o f housing, and—to ensure tha t a rem edy was

actually p rov ided10- requiring CHA to use its best efforts

“ to increase the supply o f Dwelling Units as rapidly as

possible. . . .” 11 No appeal was taken from the D istrict

C ourt’s sum m ary judgm ent or from its rem edial order.

Proceedings in the com panion litigation against HUD

were then resumed. Plaintiffs pressed their claim for relief

requiring the federal agency to assist in rem edying the

proven discrim ination, while Petitioner HUD sought

dismissal o f the case. On Septem ber, 1, 1970, the D istrict

Court granted the governm ent’s request; b u t on appeal,

summary judgm ent in favor of plaintiffs against HUD was

directed .12 The C ourt of Appeals found th a t

into a cooperative relationship with the Cook County Housing

Authority (which it did), but also had to secure agreement from

the governing body of any local political subdivision in Cook

County within whose boundaries such housing was proposed to

be located. See Brief for Petitioner, pp. 7, 29-30, 31-34. These

agreements were never secured and under the 1969 order CHA

has located no public housing outside the city limits of Chicago.

10 “-pjjg c ourt . [has] determined that the several provisions

of this judgment order are necessary to prohibit the future use and

to remedy the past effects of the defendant Chicago Housing

Authority’s unconstitutional site selection and tenant assignment

procedures, to the end that plaintiffs and the class o f persons

represented by them, Negro tenants o f and applicants for public

housing in Chicago, shall have the full equitable relief to which

they are entitled,” 304 F. Supp., at 737. See text at note 5

supra.

**304 F. Supp., at 739, 741.

12Gautreaux v. Romney, 448 F.2d 731 (7th Cir. 1971).

8

. . . the Secretary exercised the above described

pow ers in a m anner which perpetuated a racially

discrim inatory housing system in Chicago, . . . . The

fact th a t HUD knew of such circum stances is borne

ou t by the D istrict C o u rt’s specific finding in this

suit th a t HUD tried to block “ the activity com

plained of, succeeded in some respects, b u t con

tinued funding know ing of the possible action the

City Council w ould take .’’13

These HUD actions, said the C ourt o f Appeals, “ consti

tu ted racially discrim inatory conduct in their own

righ t.” 14

When the case returned to the trial court, it was

consolidated w ith the CHA litigation and plaintiffs

moved for fu rther relief, asking th a t all defendants be

required to subm it a com prehensive plan “ to rem edy the

past effects of unconstitu tional site selection in the

Chicago public housing system. . . .” Record, Vol. II,

Item No. 3 .15 The m otion alleged th a t some 30,000 units

13 Id., at 739.

14 Id. There is thus no warrant for Petitioner’s suggestion

(Brief, p. 20 n.16) that there has been “no finding o f active

misconduct by HUD.” The Court of Appeals expressly noted

that HUD had failed to undertake appropriate action to enforce

nondiscrimination by CHA, as required by the 1964 Civil Rights

Act. Id.., at 737-38. Cf. Adams v. Richardson, 351 F. Supp. 636

(D.D.C. 1972), 356 F. Supp. 92 (D.D.C.), modified in part and

aff’d, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973).

13In the interim, litigation to enforce the 1969 decree against

CHA continued. In 1970, plaintiffs’ counsel brought to the atten

tion o f the District Court the fact that, despite the injunction to

use its “best efforts” to increase the supply of dwelling units in

Chicago, and despite the specific requirement that 700 units of

public housing be built in the “General Public Housing Area,”

and despite HUD’s approval of CHA site recommendations for

1500 additional units o f public housing, CHA had as yet failed to

recommend any new sites to the Chicago City Council. Following

[ fo o tn o te continued]

9

of public housing had been im properly located in

segregated Negro neighborhoods as a result o f defendan ts’

discrim inatory policies, and th a t an appropriate m easure

of relief was therefore the location o f an additional

an extensive series of conferences between Court and counsel — at

which CHA announced that it did not wish to submit new sites

until after the April 1971 mayoralty election in Chicago — the

District Court modified its “best efforts” order by establishing

a specific timetable requiring CHA to submit site recommendations

to the City Council. CHA appealed the denial o f its motion to

vacate the timetable order, which was stayed pending its appeal,

but the Seventh Circuit affirmed the District Court’s judgment.

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, 436 F.2d 306 (7th Cir.

1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 922 (1971).

Thereafter, although CHA submitted recommendations, very

few sites in the “General Public Housing Area” received City Coun

cil approval. Upon motion, the District Court enjoined HUD

from distributing federal Model Cities program funds to the City

of Chicago until 700 public housing units in white areas had been

approved by the Mayor and Council. On appeal, entry of this

decree was held to be an abuse of discretion because HUD’s dis

criminatory activities had occurred in the context of public hous

ing, and not Model Cities, programs. Gautreaux v. Romney, 332 F.

Supp. 366 (N.D. 111. 1971), rev’d 457 F 2d 124 (7th Cir. 1972).

Following that appellate ruling, the District Court dealt

directly with the City Council’s unexplained and unjustified failure

to process CHA site recommendations in white areas by super

seding, for the purposes of this case, the Illinois statutory require

ment that CHA’s site selections be approved by the Chicago City

Council. This order was affirmed and this Court denied review.

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, 342 F. Supp. 827 (N.D.

111. 1972), a ff’d sub nom. Gautreaux v. City of Chicago, 480 F.2d

210 (7th Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1144 (1974).

As of June 30, 1975 — six years after the entry o f the first

remedial order — only nine units of public housing located in other

than predominantly Black areas of Chicago have been constructed.

(CHA Report No. 17, p, 2). The District Court has referred the

matter to a Master in an effort to determine responsibility for

this lack o f progress. Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority,

384 F. Supp. 37 (N.D. 111. 1974). mandamus denied, 511 I .2d

82 (7th Cir. 1975).

10

30,000 public housing units in integrated neighbor

hoods.16 However, it recited, the “ General Public H ous

ing A rea” rem aining w ith the city limits o f Chicago was

insufficient to support such a num ber o f additional

public housing units located in accordance w ith the 1969

decree. Hence, plaintiffs suggested th a t relief involving

construction of additional public housing w ithou t the

City of Chicago should be granted, and no ted tha t all

parties had previously expressed agreem ent upon the

desirability of a “m etropo litan” rem edy. Following fur

ther proceedings, plaintiffs on Septem ber 24, 1972

subm itted a proposed Judgm ent O rder em bodying a form

of “ m etropo litan” relief17 and hearings were held Sep

tem ber 28-29 and Novem ber 27-28, 1972.

On Septem ber 28, 1972, the CHA D irector testified

tha t CHA was applying for a new reservation o f 3500

units from HUD b u t tha t, in his opinion, 7 5% of the units

could n o t be located in w hat rem ained of the “ General

Public Housing A rea” in Chicago, as defined by the

C ourt’s 1969 decree.18 On N ovem ber 27, 1972, an

expert dem ographer tendered by plaintiffs described the

rapidly shifting racial com position of Chicago’s popula-

1 Chicago’s 1973-1980 public housing needs have been esti

mated at 67,000 new units. Northeastern Illinois Planning Com

mission, Moderate and Low-Income Housing, A Ten Year Esti

mate o f Regional Needs 12 (1973).

1 *7

Plaintiffs’ proposed decree was modeled upon the 1969

remedial order. It defined a “Limited” and “General” public

housing area in terms of the Chicago Urbanized Area rather than

the city limits, and established floors and percentages for future

site location within those areas. It suggested a mechanism whereby

the District Court might vest CHA with authority to locate units

outside the City o f Chicago if voluntary agreement o f local agen

cies could not be secured.

1 8 Record, Transcript of Proceedings, September 28, 1972, at

6 5 .

11

tion, and estim ated th a t the “ General Public Housing

A rea” as defined in the 1969 decree was being rapidly

elim inated and w ould disappear entirely by about the

year 2000 .19 Finally, plaintiffs presented a form er U.S.

Civil Rights Commission official w ho described the

pervasive role of HUD and its predecessor agencies in

creating and perpetuating racial residential segregation in

private, as well as public, housing.20 (This testim ony,

however, was stricken by the trial co u rt.)21 On Septem

ber 11, 1973, the D istrict C ourt entered its M em orandum

O pinion and Order, in which it refused even to consider

some form of “ m etropo litan” relief because

the wrongs were com m itted w ith in the lim its of

Chicago and solely against residents of the City. It

has never been alleged th a t CHA and HUD discrimi

nated or fostered racial discrim ination in the sub

urbs and, given the limits of CHA’s jurisdiction, such

claim could never be proved against the principal

offender herein .22

On appeal, the C ourt below (per Mr. Justice Clark, sitting

by designation) held tha t “m etropo litan” relief was

necessary and equitable under the facts of the case, and

was n o t inconsistent w ith this C o u rt’s decision in Milliken

v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974). The initial opinion of

the panel directed a remand

*9 Record, Transcript of Proceedings, November 27, 1972, at

85-86.

20 Id,., at 134 et seq.

Q 1

Id., at 185-86. The parties disagree on whether other evi

dence before the District Court is indicative of area-wide viola

tions by HUD. See, e.g., Brief for Petitioner, at pp. 21, 23-24.

22 Gautreaux v. Romney, 363 F. Supp. 690, 691 (N.D. 111.

1973).

12

. . . for fu rther consideration in the light o f this

opinion, to w it: the adoption o f a comprehensive

m etropolitan area plan th a t will n o t only disestab

lish the segregated public housing system in the City

of Chicago which has resulted from CHA’s and

H U D ’s unconstitu tional site selection and tenan t

assignm ent procedures b u t will increase the supply

of dwelling units as rapidly as possible.23

However, upon petition for rehearing, the C ourt of

Appeals significantly narrow ed its holding. I t reaffirm ed

its “view th a t the trial judge should n o t have refused to

‘consider the p ropriety of m etropolitan area relief’ ” 24

b u t rem anded the case

fo r additional evidence and fo r further consideration

o f the issue o f metropolitan area relief in light o f

this opinion and that o f the Supreme Court in

Milliken v. Bradley. In the m eantim e, intra-city relief

should proceed apace w ithou t further delay.25

On May 12, 1975, this C ourt granted H UD ’s petition for

a w rit of certiorari to review the C ourt of A ppeals’

judgm ent and rem and.26

28 Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, 503 F.2d 930,

939 (7th Cir. 1974).

24 Id., at 939.

25 Id., at 940 (emphasis added).

26 44 L.Ed.2d 448 (1975).

13

ARGUMENT

INTRODUCTION

Decision of the question presented for review in this

case will have broad and im portan t im plications for the

future conduct o f governmental housing program s and

related activities which have, in this and o ther instances,

been instrum ental in the past in creating or exacerbating

racial residential segregation. A fter careful consideration

of the positions taken by the respective parties and study

of the record in this m atter, however, amici have

concluded th a t the issues raised by Petitioner are n o t

appropriately presented on this record; we very respect

fully suggest th a t this C ourt should dismiss the w rit of

certiorari so tha t the m atter m ay be re tu rned to the trial

court for the taking o f evidence and fu rther proceedings

as directed by the Seventh C ircuit’s order on P etitioner’s

request for rehearing below.

Such a course o f action is appropriate here fo r tw o

reasons: first, the Petitioner in this m a tte r is so little

directly concerned w ith m ost o f the various detailed

aspects of a po ten tial remedial decree about which it

speculates and com plains, th a t it should n o t be accorded

standing to raise those issues; second, the “ scope” o f any

supposed “ in ter-d istric t” rem edy which m ay ultim ately

be fashioned in this case is so com pletely undefined on

this record tha t issues relating to its sufficiency or

justifiability are simply n o t ripe for decision by this

Court. Further proceedings in the trial court will n o t only

com plete the record, bu t will also provide ample o p po rtu

nity for the parties w ho m ight be d irectly affected to be

heard and to themselves seek such appellate review as

they deem appropriate, following the shaping o f an

equitable decree by the D istrict C ourt.

14

I.

THE WRIT OF CERTIORARI SHOULD BE DISMISSED

AND REVIEW OF THIS MATTER POSTPONED UNTIL

AFTER FURTHER PROCEEDINGS IN THE TRIAL

COURT

A. Petitioner Does N ot Have Standing To A ttack

The Judgm en t O f The C ourt O f Appeals On the

G rounds Raised In Its Petition And Brief

Because this is a case involving racial discrim ination by

the Petitioner HUD, and because the plaintiffs have

continously pressed for H U D ’s participation in a rem edy

designed to alleviate the effects of th a t discrim ination,

there is a t first blush little reason to doub t H U D ’s right to

attack, in this C ourt, a judgm ent which sends the case

back to the D istrict C ourt for reconsideration o f the kind

of rem edy w hich should be ordered. However, Petitioner

attacks n o t so m uch the C ourt of A ppeals’ judgm ent of

rem and as it does certain consequences to others which

Petitioner speculates m ay occur as the result of tha t

remand. Petitioner’s standing to seek this C o u rt’s opinion

about the po ten tia l orders which m ay be entered by the

D istrict C ourt on rem and m ust therefore be carefully

considered, for “ the question of standing is w hether the

litigant is en titled to have the court decide the m erits of

the dispute or o f particular issues.” Warth v. Seldin, 45

L .Ed.2d 343, 354 (1975) (emphasis added).

We respectfully subm it th a t Petitioner lacks the neces

sary concrete adversary interests to w arrant exercise o f

this C o u rt’s certiorari jurisdiction. The contours o f the

analysis are described in Warth, supra, 45 L .Ed.2d at

354-55:

This inquiry involves b o th constitu tional lim itations

on federal court jurisdiction and prudential lim ita

tions on its exercise. . . .

15

In its constitu tional dim ension, standing im ports

justiciability: w hether the p la in tiff has m ade ou t a

“ case or controversy” betw een him self and th a t

defendant w ithin the m eaning of A rt. III. . . . The

A rt. I ll judicial pow er exists only to redress or

otherwise to p ro tec t against injury to the com plain

ing party , even though the c o u rt’s judgm ent m ay

benefit others collaterally. . . .

. . . [T] his C ourt has recognized o ther lim its on the

class of persons who may invoke the co u rt’s

decisional and remedial powers. . . . [E] ven when

the p la in tiff has alleged injury sufficient to m eet the

“ case or controversy” requirem ent, this C ourt has

held tha t the p lain tiff generally m ust assert his own

legal rights and interests, and cannot rest his claim

to relief on the legal rights or interests o f th ird

parties. . . .

The “prudential considerations” o f Wurth apply to

Petitioner here. See 45 L .Ed.2d, at 355-56, n. 12 and

accom panying tex t. The question, therefore, is w hether

Petitioner can dem onstrate sufficient “ in ju ry” to HUD to

entitle it to litigate the issue it presents:

W hether in light of Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S.

717, it is inappropriate for a federal court to order

inter-district relief for discrim ination in public hous

ing in the absence of a finding o f an inter-district

violation. [Brief for Petitioner, at p. 2.]

Petitioner points to no language o f the C ourt o f

Appeals which com pels an order on rem and restricting

HUD in any particular w ay.27 A lthough Petitioner

°7A Consider Petitioner’s description of the trial court proceed-

ings which led to the Seventh Circuit reversal:

In the order underlying the present Petition, the dis

trict court directed HUD to use its “best efforts to

[ fo o tn o te con tinued]

16

makes m uch o f the fact that, in its view, the C ourt of

Appeals has m andated an “ in ter-d istric t” rem edy w ithou t

finding an “ inter-district v io lation” or an “ inter-district

effect” (Brief for Petitioner, a t pp. 15-28),* 28 it now here

cooperate with CHA in its efforts to increase the

supply o f dwelling units, in conformity with” all appli

cable federal statutes, HUD rules and regulations, and

the provisions of the judgment against CHA and all

other final orders in this litigation . . . .

[Petitioner has expressed no objection to this decree.]

The district court rejected the order proposed by

Respondents, which would have directed CHA and

HUD to use their best efforts to provide dwelling

units outside the City of Chicago in Cook, DuPage

and Lake Counties, and refused to conduct additional

proceedings designed to develop a plan of metropol

itan area-wide relief . . . .

(Brief for Petitioner, at pp. 9, 10). The Court of Appeals, however,

did not direct the District Court to enter the order proposed by

the plaintiffs (see note 16 supra). It did not direct the lower

court to require HUD to use its best efforts to provide dwelling

units outside Chicago without regard to “all applicable federal

statutes, HUD rules and regulations,” etc. It merely directed the

trial court to conduct further proceedings in light o f its opinion

and that of this Court in Milliken v. Bradley, supra.

28 The Seventh Circuit’s remand does not require a metro

politan housing remedy, but rather reconsideration in light of

Milliken v. Bradley, supra. Any doubt on this score was resolved

by the Court’s Order on Rehearing, which deliberately omitted

language describing the result which was to flow from the further

proceedings. 503 F.2d, at 940. The Order (mandate) o f the Court

of Appeals, issued August 26, 1974, merely states that the District

Court’s judgment is reversed and

this cause be and the same is hereby REMANDED to

the said District Court for further consideration in

accordance with the opinion of this Court filed this

day.

(No separate order was issued following consideration and dis

position of HUD’s petition for rehearing, although the opinion

of the Court was amended as described above, p. 12, supra.)

[ fo o tn o te con tinued]

17

indicates how the specific provisions of the decree

affecting HUD will differ as a result o f the Seventh

C ircuit’s rem and. Of course, it cannot, since no particular

form of rem edy has been directed pending reconsidera

tion of the m atter by the trial court.

Petitioner instead attacks the rem and on tw o grounds.

The first—tha t the record does no t, in P e titioner’s view,

m eet the Milliken standards for “ in ter-d istric t” relief—is

considered infra, pp. 19-25. The second is Petitioner’s

claim th a t an inter-district rem edy which requires the

construction of public housing outside Chicago, over the

objection of local agencies or jurisdictions, will entail

immense practical difficulties. But the practical problem s

discussed at great length in P etitioner’s b rief (pp.

28-40) all affect th ird parties, none o f whom is before

this C o u r t . N o plan will be form ulated or ordered until 29

Petitioner thus errs in opening its argument by contending

that the Seventh Circuit remanded this case “for ‘the adoption of

a comprehensive metropolitan area plan’ (Pet. App. 59a)” as though

that statement in the initial opinion of the panel were not modified

by the terms o f the Order denying HUD’s petition for rehearing.

29

Petitioner opens its argument on the merits as follows (Brief,

pp. 15-16):

The court of appeals, by remanding this case to the

district court for “the adoption of a comprehensive

metropolitan area plan” (Pet. App. 59a), has departed

from the long-standing rule of federal equity practice

that “the nature of the violation determines the scope

of the remedy.” Swann v. Board o f Education, 402

U.S. 1, 16. See also Brown v. Board o f Education,

349 U.S. 294, 300. The state and local agencies that

are made subject to the district court’s remedial orders

by that decision (see p. 12, supra), with the exception

of CHA itself, have not been implicated in any unlaw

ful discrimination; they have in effect been consoli

dated for remedial purposes by the court of appeals

apparently solely because the court believed that met

[ fo o tn o te c o n tinued]

18

after such parties have been jo ined and heard (see Brief

for Petitioner, at p. 12).30 Clearly, in this case nothing

respecting “ m etropo litan” relief has yet occurred which

so d irectly affects Petitioner’s interests as to w arrant this

C ourt in reviewing the judgm ent below at Petitioner’s

request. Possible injury to third parties does no t confer

standing upon a litigant unless very unusual circumstances

(not present here) make direct assertion of a claim by

the injured parties im probable. Warth v. Seldin, supra,

45 L .Ed.2d, at 355-56.

The Petitioner, despite H lJD ’s ongoing relationship

w ith local agencies and political subdivisions, is no t

en titled to judicial recognition as the p ro tec to r of their

interests in litigation which does n o t directly affect HUD.

See County Court o f Braxton County v. State ex rel.

Dillon, 208 U.S. 192 (1908) (county governing body

m em bers have no standing to attack, in Supreme Court,

West Virginia sta tu te whose effect will be to require

co u n ty ’s default on bonds; only bondholders w ould have

standing); Diaz v. Patterson, 263 U.S. 399 (1923)

(fraudulent titleholder w ho unsuccessfully sued to estab

lish his claim m ay n o t a ttack judgm ent of trial court on

ground tha t court did n o t determ ine w hether th ird

ropolitan area-wide residential desegregation is a desir

able goal of social policy. That judicial view of

desirable social policy does not, standing alone, jus

tify the award of inter-district relief. Milliken v.

Bradley, 418 U.S. 717. [Emphasis added.]

30 We do not interpret Judge Austin’s Order permitting the

filing o f the Second Supplemental Complaint and adding additional

parties defendant as an adjudication on the merits against these

parties. Rather, it seems to us, the District Court has wisely

determined to have all potentially affected parties before it when

it reconsiders the question o f metropolitan relief pursuant to the

Seventh Circuit’s remand. Cf. Milliken v. Bradley, supra, 418

U.S., at 752.

19

parties m ay have had b e tte r title than defendant); ICC v.

Chicago, R.I. & P.R. Co., 218 U.S. 88 (1910) (railroad

may n o t a ttack ICC judgm ent reducing through rates on

petition o f shippers on ground tha t ICC left local rates

unaltered, since effect of fu rther action by ICC w ould

no t benefit, bu t further injure, railroads); c f Massa

chusetts v. M ellon , 262 U.S. 447 (1923).

The only direct effect upon Petitioner o f the Seventh

C ircuit’s order is to lift from it an injunctive decree to

which it did n o t object. (See no te 27 supra.) A fter

further proceedings take place, Petitioner may becom e

subject to another injunctive decree, bu t there will be

ample o p po rtun ity a t tha t tim e to seek review of its

provisions. There is, in sum, no th ing about which

Petitioner m ay properly com plain since the C ourt of

Appeals neither im posed any restrictions upon Petitioner

nor denied relief which Petitioner sought. Thus, the

“prudential considerations” identified in Warth counsel

against according standing to HUD to litigate the “ in ter

district” issues it fears the D istrict C ourt may address

on rem and. Since Petitioner lacks standing, the w rit o f

certiorari should be dismissed. Pen fie Id Co. v. SEC, 330

U.S. 585 (1947).

B. The Record In This M atter Is Insufficient To

Perm it Decision O f The C onstitu tional Claim Raised

By Petitioner.

Petitioner seeks to have this C ourt answer a legal

question which was never resolved by the trial court,

which is posed in the abstract because it was never

the focus of evidentiary p resen ta tion ,31 and which will

SI -The District Court explicitly refused to consider the very

evidence which Petitioner now asserts is essential. Sec text at

notes 19, 20, supra.

20

be the subject o f inquiry by the trial court pursuant

to the judgm ent below. Because this record is inade

quate to perm it a reasoned disposition of the claim

presented by Petitioner, the w rit o f certiorari should be

dismissed as im providently granted.

This record could hardly be m ore opaque w ith respect

to the question presented by Petitioner to this C ourt:

W hether, in light of Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S.

717, i t is inappropriate for a federal court to order

inter-district relief for discrim ination in public hous

ing in the absence of a finding of an inter-district

violation.

(Brief for Petitioners, at p. 2.) As we earlier po in ted

o u t,32 the C ourt of A ppeals’ disposition o f this m atter

did not require adoption o f a “m etropolitan area p lan .”

Its judgm ent did n o t “m a [k ]e subject to the district

c o u rt’s rem edial orders” the additional parties jo ined

upon m otion o f the plaintiffs (compare Brief for Peti

tioners, at p. 15). T hat judgm ent certainly did not direct

th a t injunctive decrees be entered against these parties

irrespective o f their “ im plication in any unlaw ful discrim

ination [or its effects] ” (id.) bu t instead instructed the

trial cou rt to decide w hether relief against such parties

was appropriate under the principles of this C ourt’s

decision in Milliken v. Bradley. A nd by no stretch of the

im agination can the C ourt of A ppeals’ ruling be said to

have “ consolidated” either the fourteen new parties

defendant or the “ m ore than 3 00” political jurisdictions

to which Petitioner subsequently refers in the course of

the in terrorem argum ent which it constructs (Brief for

Petitioner, at p. 36.)

32 See no te 28 supra.

21

If the “ finding” of an “ in ter-d istric t” violation or

effect (Milliken v. Bradley, supra) is critical, then the

C ourt of Appeals was em inently correct in rem anding the

case so as to perm it the parties to present evidence and

the D istrict C ourt to make such a finding if w arranted by

tha t evidence.33 Since the case was heard in the D istrict

C ourt long before Milliken was decided, neither the court

nor the parties (including HUD) anticipated the poten tial

relevance of such a finding. Cf, 503 F.2d, a t 934 .34 The

C ourt of Appeals reversed and rem anded no t because it

posited “ in ter-d istric t” relief w ithou t the necessary find

ing, b u t because the D istrict C ourt im properly refused

even to consider such relief. Id,, a t 939. Plainly, the issue

described by Petitioner is no t in this case because the

C ourt of Appeals has done no m ore than afford an

opportun ity for the D istrict C ourt to receive evidence

and to make such findings as are w arranted by the

evidence.

O f even greater significance is the absence of specific

remedial directions in the rem and. N ot only does the

C ourt o f A ppeals’ order fail ipso facto to subject agencies

who were n o t parties to the suit to fu tu re remedial

33 See note 31 supra.

34 See Massachusetts v. Painten, 389 U.S. 560, 561 (1968):

At the time of respondents’ trial in 1958, Massachu

setts did not have an exclusionary rule for evidence

obtained by an illegal search or seizure . . . and the

parties did not focus upon the issue now before us.

After oral argument and study o f the record, we have

reached the conclusion that the record is not suffic

iently dear and specific to permit decision o f the im

portant constitutional questions involved in this case.

The writ is therefore dismissed as improvidently granted

22

decrees, or to “ consolidate” them , b u t it leaves wholly

undefined the nature and scope of any “m etropo litan”

plan which m ight be ordered on rem and. It is far from

unreasonable to assume—especially in light o f the

D istrict C ourt’s cautious, step-by-step approach to rem

edy th roughou t the course o f this litigation35 — th a t the

court m ay fashion “ m etropo litan” relief which is no t

“ in ter-d istric t” in the Mil liken sense. F or instance, as the

Brief o f R espondents details, Petitioner HUD adm inisters

its housing programs by “ m arket areas,” of which the

Chicago Housing M arket A rea is an exam ple. Consistent

w ith existing sta tu to ry law ,36 the D istrict C ourt m ight

on rem and restrain HUD from financing housing p ro

grams th roughou t the entire Chicago Housing M arket

A rea unless they m eet the siting and tenan t assignment

requirem ents established in the 1969 intra-Chicago de

cree.

Such a rem edy w ould be “m etropo litan” or area-wide,

b u t it w ould involve no decrees against new parties to the

lawsuit, and it would n o t be “ in ter-distric t” in the

Milliken sense. I t w ould n o t take away from local

jurisdictions any rights they have to determ ine w hether

to participate in federal housing programs (see Brief for

Petitioner, a t p. 36).37 It would simply amplify the

conditions (which local public housing programs already

D See pp. 6-9, supra.

36 42 U.S.C. §5301 (c)(6): “ . . . Federal assistance provided

in this chapter is for the support of community development

activities which are directed toward . . . the spatial deconcen

tration of housing opportunities for persons of lower income . . . .”

See also, 42 U.S.C. §§1439(a)(3)-(4), 5304(a)(4)(c)(ii).

0 7

3 The Housing and Community Development Act o f 1974

authorizes HUD to bypass local governmental entities in some

instances. Sec 42 U.S.C. § § 1437f(b)(l)-(2).

23

m ust m eet) to be considered by a locality when

m aking its decision. Cf. Kelsey v. Weinberger, 498 F .2d

701 (D.C. Cir. 1974). Such a decree w ould n o t “ subject

suburban governm ental agencies . . . to substantial finan

cial and adm inistrative burdens” (id., at p. 35) unless

those agencies undertook to participate in federal housing

programs. What such a decree would do is to require

HUD to operate federal housing program s w ithin the

Chicago Housing M arket Area in such a fashion as to

alleviate the racial residential segregation which it helped

to create.

A variety o f o ther rem edial approaches is appropriate

under the judgm ent of rem and entered by the C ourt of

Appeals. For exam ple, the D istrict C ourt m ight direct

HUD to act directly to provide additional housing units

outside the City of Chicago pursuant to the “bypass”

provisions o f the Housing and C om m unity D evelopm ent

A ct of 1974.38 39 * * 42

These rem edial steps are a long way from the h ypo the

tical decree which Petitioner assumes will be entered on

rem and (Brief for Petitioner, at pp. 35-40). Petitioner

suggests tha t the C ourt of A ppeals’ ruling will necessarily

deprive local jurisdictions of decision-making pow er w ith

respect to undertaking public housing program s, over

zoning and land use control, for provision of public

services, etc., so as to constitu te the D istrict C ourt, “ in

38 See Brief for Respondents in Opposition to Certiorari, at

p. 13.

aq

42 U.S.C. §1437f(b)(l) provides: “ . . . In areas where . . . the

Secretary determines that a public housing agency is unable to

implement the provisions of this section, the Secretary is author

ized to enter into such contracts and to perform the other func

tions assigned to a public housing agency by this section.” See

also, 42 U.S.C. § 1437(b)(2).

24

significant ways . . . the m aster m etropolitan govern

m en t” {id., a t 27). Such an assum ption is unw arranted

on this record.

U nquestionably, this C ourt’s judgm ent about the

appropriateness, under Milliken v. Bradley, o f a decree

which m ay be en tered by the D istrict C ourt pursuant to

the Seventh C ircuit’s rem and in this case will depend

upon the exact natu re of th a t decree. The questions of

constitu tional pow er and equitable discretion posed on

the one hand by a decree against HUD alone, and on the

o ther hand by a decree which purports to restric t the

governm ental powers o f local jurisdictions in the m anner

suggested by Petitioner, will be m arkedly dissimilar.40

But the record in this case, in its present form , is simply

inadequate to perm it the C ourt to determ ine exactly

w hat sort o f decree the trial court will in fact enter.

T raditionally, where such uncertain ty of interpreting

the opinion or judgm ent below has becom e apparent, and 40

40 Thus, the issue presented by Petitioner is not ripe for review.

Wheeler v. Barrera, 417 U.S. 402, 426-27 (1974):

The second major issue is whether the Establishment

Clause of the First Amendment prohibits Missouri from

sending public school teachers paid with Title I funds

into parochial schools to teach remedial courses. The

Court o f Appeals . . . [held] the matter was not ripe

for review. We agree. As has been pointed out above,

it is possible for the petitioners to comply with Title

I without utilizing on-the-premises parochial school

instruction. Moreover, even if, on remand, the state

and local agencies do exercise their discretion in favor

of such instruction, the range of possibilities is a broad

one and the First Amendment implications may vary

according to the precise contours of the plan that is

formulated . . . .

. . . A federal court does not sit to render a decision

on hypothetical facts . . . .

25

where tha t uncertain ty can be clarified by fu rther

proceedings in the same, or even another, m atter, this

C ourt has declined to pass upon constitu tional questions

in the abstract and has dismissed writs of certiorari as

im providently granted. E.g., Parker v. County o f Los

Angeles, 338 U.S. 327 (1949); Rescue A rm y v. Municipal

Court, 331 U.S. 549 (1947); Alabama State Federation

o f Labor v. M cAdory, 325 U.S. 450 (1945); CIO v.

M cAdory, 325 U.S. 472 (1945); c f Wheeler v. Barrera,

note 39 supra. That, we suggest, is the m ost appropriate

disposition in this m atter as well.

II.

SHOULD THIS COURT REACH THE MERITS, THE JUDG

MENT BELOW SHOULD BE AFFIRMED BECAUSE IT IS

CONSISTENT WITH MILLIKEN V. BRADLEY

We have suggested above th a t the proper disposition of

this case is to dismiss the w rit o f certiorari, b o th because

Petitioner lacks standing to argue the issue it presents for

review and because this record is an insufficient basis

upon which to determ ine the constitu tional question

presented by Petitioner. Should the C ourt consider the

case on the m erits, however, we believe th a t Respondents

are entitled to prevail.

The thesis o f the P etitioner’s argum ent is th a t the

Seventh C ircuit’s ruling in this case conflicts w ith, or

erroneously in terprets, the opinion in Milliken v. Bradley,

supra. Since (as we have explained above) the judgm ent

of the C ourt o f Appeals m erely rem ands to the D istrict

C ourt for reconsideration o f “ m etropo litan” relief in

light, inter alia, of Milliken, there is no basis upon which

to alter tha t judgm ent. A lthough the opinion of the

C ourt of Appeals is strongly supportive o f the concept of

m etropolitan relief, the rem and order anticipates tha t the

26

D istrict C ourt will receive additional evidence and make

specific findings before undertaking a fresh determ ination

on rem edy. Thus, Petitioner will have an adequate

opportun ity on rem and to disprove w hat it has term ed

m istaken assum ptions or erroneous factual in terpreta

tions by the C ourt o f A ppeals.41 Should the case then be

reappealed b y any party , we tru st tha t the record would

contain specific factual findings by the D istrict C ourt on

the subjects of inquiry necessitated by b o th the Seventh

C ircuit’s opinion and M ilhken .42 Such a record would

perm it com plete appellate review.

In contrast, reversal o f the judgm ent below w ould

am ount to a holding by this C ourt tha t “m etropo litan ,”

“ in ter-d istric t,” or “ area-wide” relief in a segregation case

is never appropriate, w hether “ inter-district violations,”

“ inter-district effects,” or simply “ area-wide” discrimina

41

Neither the parties nor the District Court can be faulted for

the present inadequate state of the record on the subject of “inter-

district effects,” since the evidentiary hearing which led to the

District Court’s order took place in September and November,

1972 — a year and a half before this Court rendered its opinion

in Milliken. Pursuant to the Court of Appeals’ remand, plaintiffs

may offer additional evidence about HUD’s area-wide violation and

the appropriate remedy therefor, in addition to the evidence pre

viously offered but refused by the District Court. HUD, or any

added party, may attempt to rebut both the present evidence of

record and any such additional evidence, or may propose such

remedial alternatives as it deems fit. The District Court will then,

for the first time in this litigation, make specific findings on the

relevant issues.

42 No longer bound by its unnecessarily narrow, pre-Milliken

view o f the case, the District Court will consider the nature and

scope of the violations by HUD or any other parties, the range of

remedies available against HUD and/or any other parties, and the

appropriateness of those remedies to vindicate plaintiffs’ rights

to nondiscriminatory housing opportunities guaranteed by, inter

alia, the Thirteenth Amendment, the 19b4 and 1968 Civil Rights

Acts, and the 1974 Housing and Community Development Act.

27

tion can be proved. We do n o t believe the C ourt w ent so

far in Milliken, nor tha t the door to m eaningful relief

from unlaw ful housing segregation should be so firmly,

and precipitously, shut in this case. A ccordingly, we

subm it tha t if the case is considered on its m erits, the

judgm ent below m ust be affirm ed.

CONCLUSION

W HEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, amici re

spectfully suggest tha t the w rit of certiorari herein should

be dismissed, or in the alternative th a t the judgm ent

rem anding the case for fu rther proceedings should be

affirm ed.

Respectfully subm itted,

J. Ha r o l d F la nn ery

Paul R . D im ond

Willia m E . C aldw ell

N orman J . Chachkin

520 W oodward Building

733 - 15th S treet, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

N a th a n iel R. J ones

General Counsel, N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys fo r Amici Curiae.