Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Flaherty Brief for the Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1994

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Flaherty Brief for the Appellant, 1994. b729f407-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/00191d96-f92a-4020-b564-16a785357f04/commonwealth-of-pennsylvania-v-flaherty-brief-for-the-appellant. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

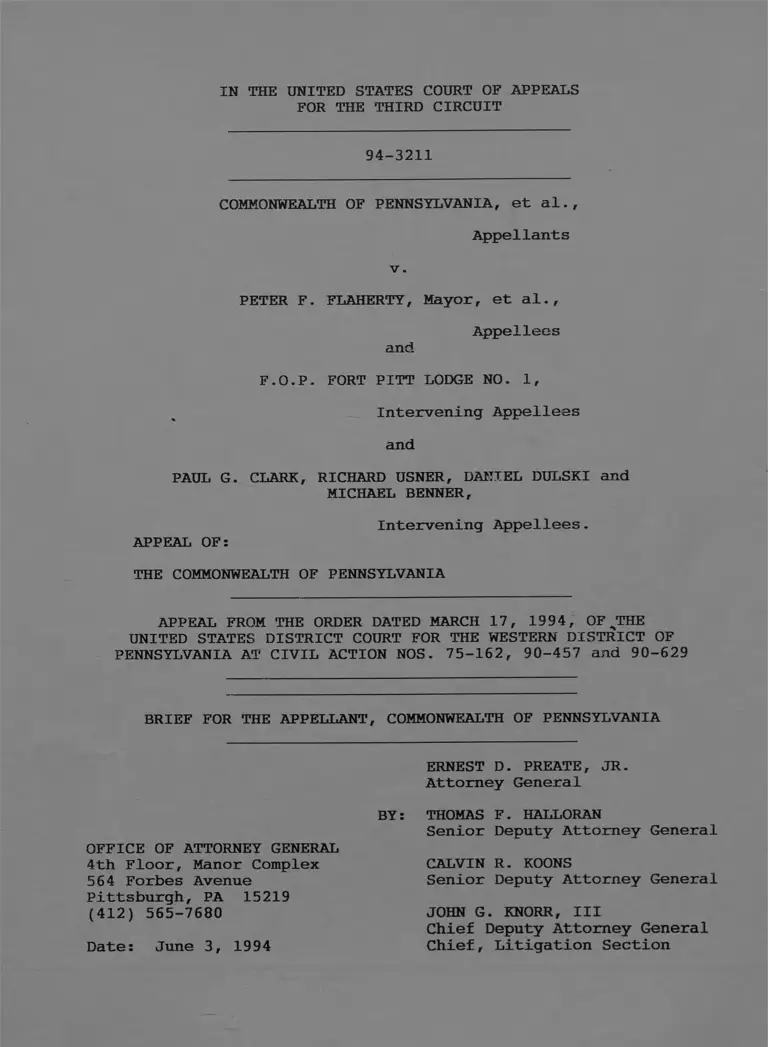

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

94-3211

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, et al..

Appellants

v.

PETER F. FLAHERTY, Mayor, et al.,

Appellees

and

F.O.P. FORT PITT LODGE NO. 1,

Intervening Appellees

and

PAUL G. CLARK, RICHARD USNER, DANIEL DULSKI and

MICHAEL BENNER,

Intervening Appellees.

APPEAL OF:

THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA

APPEAL FROM THE ORDER DATED MARCH 17, 1994, OF ̂ THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF

PENNSYLVANIA AT CIVIL ACTION NOS. 75-162, 90-457 and 90-629

BRIEF FOR THE APPELLANT, COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA

ERNEST D. PREATE, JR.

Attorney General

BY: THOMAS F. HALLORAN

Senior Deputy Attorney General

CALVIN R. KOONS

Senior Deputy Attorney General

JOHN G. KNORR, III

Chief Deputy Attorney General

Chief, Litigation Section

OFFICE OF ATTORNEY GENERAL

4th Floor, Manor Complex

564 Forbes Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

(412) 565-7680

Date: June 3, 1994

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF CITATIONS............................................ ii

STATEMENT OF JURSI DICTION.................................... 1

STATEMENT OF ISSUE PRESENTED FOR REVIEW...................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE........................................ 3

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS....................................... 4

STATEMENT OF RELATED CASES AND PROCEEDINGS................... 9

STATEMENT OF THE STANDARD OR SCOPE OF REVIEW................. 10

ARGUMENT:

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN HOLDING

THAT THE COMMONWEALTH OF

PENNSYLVANIA A CIVIL RIGHTS

PLAINTIFF DEFENDING AN INJUNCTION

ENTERED BY THE DISTRICT COURT TO

ALLOW WOMEN AND AFRICAN AMERICANS TO

BE PITTSBURGH POLICE OFFICERS,

SHOULD BE LIABLE FOR 75% OF THE

INTERVENING DEFENDANTS' ATTORNEYS

FEES WITHOUT FINDING THAT THE

COMMONWEALTH'S ACTION WAS FRIVOLOUS,

UNREASONABLE OR WITHOUT FOUNDATION........... 10

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN HOLDING

THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA

LIABLE FOR ATTORNEYS FEES OF THE

INTERVENING DEFENDANTS PURSUANT TO

FED.R.CIV.P. 41(b).......................... 16

CONCLUSION.................................................... 19

OPINIONS OF THE DISTRICT COURT - September 9, 19 91.....

- December 16, 1991.....

- August 23, 1993.......

- March 17, 1994........

CERTIFICATE OF ADMISSION TO THE BAR OF THE THIRD CIRCUIT

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

1

<! CQ U

Q

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Page

Cases:

Baum v. Masloff,

C.A. No. 90-60 (W.D. Pa)............................... 9

Christiansburq Garment Co. v. EEOC,

434 U.S. 412 (1978)........................10,11,12,14,15,16

Commonwealth v. Flaherty,

983 F . 2d 1267 (1993)............................ 8,9,10,15,16

Commonwealth v. Flaherty,

404 F. Supp. 1022 (W.D. Pa. 1975)...................... 4

Commonwealth v. Flaherty,

760 F.Supp. 472 (W.D. Pa. 1991)........................ 6,7

Hayman Cash Register Co. v. Sarokin,

669 F . 2d 165 (1982).................................... 17

Newman v. Piqqie Park Enterprises, Inc.,

308 U.S. 400 (1968).................................... 11

Poulis v. State Farm Fire & Gas Co.,

747 F . 2d 868-69 (3d Cir. 1984)......................... 18

Slater v. City of Pittsburgh,

C.A. No. 90-457 (W.D. Pa.)............................. 9

Swietlowich v. County of Bucks.

610 F . 2d 1164 (3d Cir. 1979 ).....................1 .... 18

Washington v. Davis.

426 U.S. 229 (1976 ).................................... 4,5

Statutes;

28 U.S.C. § 1291................

28 U.S.C. § 1331................

28 U.S.C. § 1343 ...............

42 U.S.C. § 1988.......... .....

Rules:

Fed.R.Civ.P. 41(b) 2,3,8,16,17,18

ii

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

This is an appeal from a final judgment over which this

Court has jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1291. The

jurisdiction of the district court was based upon 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331

and 1343. The District entered the Order quantifying an award of

attorneys fees against the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania plaintiffs

in this civil rights action and in favor of the intervening

defendants on March 17, 1994. The notice of appeal was filed on

April 15, 1994.

1

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

I. WHETHER THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN HOLDING

THAT THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, A CIVIL

RIGHTS PLAINTIFF DEFENDING AN INJUNCTION

ENTERED BY THE DISTRICT COURT TO ALLOW WOMEN

AND AFRICAN AMERICANS TO BE PITTSBURGH POLICE

OFFICERS, SHOULD BE LIABLE FOR 75% OF THE

INTERVENING DEFENDANTS' ATTORNEYS FEES WITHOUT

FINDING THAT THE COMMONWEALTH'S ACTION WAS

FRIVOLOUS, UNREASONABLE OR WITHOUT FOUNDATION?

The issue was framed by the intervening defendants'

Motion for Award of Attorneys Fees and the Commonwealth's

responses. (A - 238, 270, 326, 331). The district court granted

the motions. (Opinions dated September 9, 1991), and denied

subsequent motions to alter or amend or for reconsideration.

(Opinions dated December 16, 1991 and August 23, 1993). Fees were

quantified by order of March 17, 1994 (Opinion dated March 17,

1994). The standard of review is whether or not the district court

applied correct legal precepts in reaching the conclusion that the

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, a civil rights plaintiff, should be

liable for attorneys fees and costs under 42 U.S.C. § 1988.

II. WHETHER THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN HOLDING

THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA LIABLE 75% OF

THE ATTORNEYS FEES OF THE INTERVENING

DEFENDANTS PURSUANT TO FED.R.CIV.P. 41(b) AS

AN ALTERNATIVE TO DISMISSAL AFTER THE DISTRICT

COURT DENIED THE MOTION TO DISMISS FOR FAILURE

TO PROSECUTE AND THAT DECISION WAS AFFIRMED B.Y

THIS COURT?

This issue was presented to the district court in the

intervening defendants' Motion to Dismiss for Failure to Prosecute

(A - 234), which was denied. (Opinion dated September 9, 1991).

In an opinion addressing the Motion for Reconsideration of the

Commonwealth regarding the award of attorneys fees against it, the

district court relied upon Fed.R.Civ.P. 41(b). (Opinion dated

August 23, 1993). The standard of review is whether or not the

district court applied correct legal precepts in holding the

Commonwealth liable for attorneys fees as a sanction under

Fed.R.Civ.P. 41(b).

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The appellant herein and one of the plaintiffs below is

the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Appellees are the intervening

defendants below, four white male applicants for the Pittsburgh

Police Department.1 This is the Commonwealth's appeal from the

March 17, 1994 order of the district court quantifying an award of

attorneys fees in favor of the four white males and the orders

establishing that liability. (Copies of the Orders dated September

9, 1991, December 16, 1991, August 23, 1993, and March 17, 1994 are

attached).

This case, now in its last stage, evolves from the

district court's order dissolving its 1975 preliminary injunction

that altered the way the City of Pittsburgh hired its police

officers. The question presented by this appeal is whether the

district court's decision to impose attorneys fees against the

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the plaintiff in this action was

correct. The district court awarded fees pursuant to § 1988 of the

Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1988, but did not find”*the action

frivolous, unreasonable or without foundation. It also held that

fees were an appropriate sanction under Fed.R.Civ.P. 41(b) as an

alternative to dismissal although the motion to dismiss had

previously been denied. *

Additional plaintiffs in the district court included the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the

Guardians of Greater Pittsburgh, and the National Organization of

Women. They were not ordered to pay any attorney fees. Additional

defendants below include the City of Pittsburgh and its officials,

and the Fraternal Order of Police, also an intervening defendant.

3

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. 1975 Injunction - Flaherty I

In 1975 an injunction was issued by the district court

based upon its finding that the hiring practices of the Pittsburgh

Police Department violated §§ 19 81 and 19 83 of the Federal Civil

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1981 and § 19 83, and the thirteenth and

fourteenth amendments. See Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v.

Flaherty, 404 F.Supp. 1022 (W.D. Pa. 1975) ("Flaherty I").

One of the plaintiffs and parties moving for the

injunction was the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. After hearing,

the district court in Flaherty I found that the City had virtually

eliminated the hiring of African Americans and women as police

officers. The district court required the City, for every white

male hired, to hire one white female, one black female, and one

black male.

The City did not appeal the preliminary injunction order.

However, over the years the order withstood challenges from

applicants to the police force and the Fraternal Order of Police.

In 1977, the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP), an intervening

defendant, moved to dissolve the injunction relying on the Supreme

Court's 1976 in Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976). The

district court denied the motion to dissolve the preliminary

injunction based upon Washington v. Davis because the FOP did not

have standing. No appeal was taken. (A - 93 through 100).

4

The injunction withstood another challenge in 1984 when

a white male who had continously applied for a position as a

Pittsburgh Police Officer since 1975 moved to intervene in this

action to challenge the injunction. The district court denied the

motion, finding it was untimely, failed to allege changes in

circumstances or law which effected the basis of the original

order, and that the intervening defendant had failed to advance any

argument that had not been thoroughly presented and considered

before entry of the original order. The district court also

observed that when it granted the preliminary injunction in 1975,

it had recognized that although it was only affording interim

relief, the remedy would require a long period of time because of

the small number of vacancies that ocur in the police department.

The district court also noted that the motion to intervene failed

to allege that the disproportion, which was a result of past

discriminatory hiring practices, had ended. (A - 101 through 113).

This Court affirmed the decision of the district court.

(No. 84-3639). Mulvey filed a petition for writ of certiorari to

the United States Supreme Court at No. 85-136, referring to

Washington v. Davis as a change in the law supporting the

injunction's dissolution. The Supreme Court denied the petition.

5

B. 1991 - Dissolution of the Injunction - Flaherty II

Commonwealth v. Flaherty, 760 F.Supp. 472 (W.D. Pa. 1991)

In 1990, Paul G. Clark, Richard Usner, Michael Benner and

Daniel Dulski, white male applicants and intervening appellees,

filed two separate complaints against the City of Pittsburgh and

its officials challenging the hiring system imposed by the

preliminary injunction. (A - 114, 119). The four applicants also

moved to intervene in this 1975 action. Their motions were

granted. (A - 143, 154, 161, 168, 178). The two separate lawsuits

were consolidated with this 1975 action.

By order dated March 20, 1991, the district court granted

the intervening defendants' motion to dissolve the injunction.2

Prior to that decision, the district court noted that "We no longer

have the original presiding judge with us, and we just had a

preliminary injunction that was treated by everybody as the law."

That is, as a permanent injunction. (A - 806, 831). Ruling on the

motion to dissolve the injunction, the district court noted that

although it had before it the Commonwealth's "persuasive case that

reliance on examination scores as the primary factor in hiring will

favor whites and males over minorities and women," Flaherty II,

760 F.Supp. at 488, and evidence which supported its finding that

2The Honorable Gerald Weber issued the original injunction in

1975. After Judge Weber's death, the case was transferred to the

Honorable Maurice B. Cohill, Jr., Chief Judge of the united States

District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania, who

presided over the hearing and entered the decision and order

dissolving the injunction, as well as the order entering partial

summary judgment and attorney fees. The subject of this appeal is

the award of attorneys fees.

6

there was "no doubt that should the injunction be dissolved, it

will have an [adverse] impact on the hiring of blacks and women."

(Id.]. The court also found, "[i]f the preliminary injunction is

dissolved, the most likely result will be most police officers

hired will be white males, a few will be black males, and very few

will be women." Flaherty II, 760 F.Supp. at 480. The Commonwealth

appealed the dissolution of the injunction to this Court at No. 91-

3303. That appeal was dismissed as moot because the district court

granted the intervening defendants' Motion for Partial Summary

Judgment while the appeal was pending.

C. The September 9, 1991 Entry of Partial Summary

Judgment and Attorney Fee Award_______________

On September 9, 1991, the district court granted partial

summary judgment in favor of the intervening defendants and the

City on the claim of discrimination in the hiring of police

officers and denied the intervening defendants' motion to dismiss

for failure to prosecute. The summary judgment granted was only

partial because it related only to the portion of ^litigation

relating to the hiring of police officers and did not effect the

portion of the case relating to police officer promotions. The

district court also granted the intervening defendants' petitions

for attorney fees incurred in obtaining the dissolution of the

injunction, assessing 75% of the fees against the plaintiff

Commonwealth, and 25% against the defendant City of Pittsburgh.

The district court concluded that the parties should be realigned

so that the intervening defendants should be treated as plaintiffs

and the plaintiff Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the defendant

7

City of Pittsburgh should be treated as defendants for the purposes

of awarding fees under 42 U.S.C. § 1988. (Opinion dated September

9, 1991).

On appeal, both the granting of summary judgment and

denial of the motion to dismiss for failure to prosecute were

affirmed. The appeal of attorneys fees award was dismissed because

it had not been quantified and was therefore not a final order.

Commonwealth v. Flaherty, 983 F.2d 1267 (1993).

D . 1993 Denial of the Commonwealth's Motion for Reconsideration

On remand, the Commonwealth moved for reconsideration of

the district court's order granting fees. Although the district

court "granted" the motion for reconsideration,3 it did so merely

to reaffirm its order of attorneys fees against plaintiff

Commonwealth on the basis of 42 U.S.C. § 1988 and added reliance

upon Fed.R.Civ.P. 41(b). (A - 388 and Opinion dated August 23,

1993) . Subsequently, the attorneys fees requested by the

intervening defendants were quantified at a total of "$80,000.00,

the Commonwealth to pay $60,000.00. (Opinion dated March 18,

1994) . This appeal followed.

3An interlocutory appeal at No. 93-8084 was requested. The

request was denied on October 13, 1993.

8

STATEMENT OF RELATED CASES AND PROCEEDINGS

Counsel for appellant is unaware of any case presently on

appeal or about to be presented that involves the same or similar

issues as those raised in this appeal. This case has previously

been appealed at Court of Appeals Nos. 79-2706, 82-5629, 83-5570,

84-3095, 84-3639, 91-3303 (dismissed as moot), 92-3031, and 93-8084

(Petition for Allowance of Appeal denied). The only reported

decision on appeal was at No. 92-3031, 983 F.2d 1267 (3d Cir.

1993) .

Two cases Slater v. City of Pittsburgh, C.A. No. 90-457

(W.D. Pa.) and Boehm v. Masloff, C.A. No. 90-69 (W.D. Pa.) were

consolidated with Commonwealth v. Flaherty, C.A. No. 75-162 (W.D.

Pa.). Prior to consolidation, however, this Court heard an appeal

at No. 90-3411, affirming the district court's dismissal of Michael

Slater as an intervening defendant for lack of standing. The

Commonwealth was not a party to C.A. Nos. 90-457 and 90-629.

9

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN HOLDING

THAT THE COMMONWEALTH OF

PENNSYLVANIA, A CIVIL RIGHTS

PLAINTIFF PROTECTING THE RIGHTS OF

AFRICAN AMERICANS AND WOMEN TO BE

PITTSBURH POLICE OFFICERS, SHOULD BE

LIABLE FOR 75% OF THE INTERVENING

DEFENDANTS' ATTORNEYS FEES WITHOUT

FINDING THAT THE COMMONWEALTH'S

ACTION WAS FRIVOLOUS, UNREASONABLE

OR WITHOUT FOUNDATION.

In a decision which this Court has characterized as

"highly unusual" (983 F.2d at 1275) and which the district court

has itself characterized as "perhaps unprecedented" (Opinion dated

August 23, 1990, p. 7) the district court imposed attorneys fees

against the Commonwealth, the plaintiff in a civil rights action

brought to vindicate the rights of women and African Americans.

The district court did not find that the Commonwealth had brought

a frivolous action, but rather that fees were appropriate because

it failed to take action to dissolve what had become a "legally

guestionable" preliminary injunction which had sixteen years

earlier been entered in its favor. The court's holding is in

direct conflict with decision in Christiansburg Garment Co. v.

EEOC, 434 U.S. 412 (1978) in which the court cautioned that "post

hoc reasoning" and "hindsight logic" should not be used to award

fees against a civil rights plaintiff unless the lawsuit filed is

found to have been unreasonable or without foundation. Id. at 420.

The district court did not and could not have made such a finding

and its judgment must now be reversed.

In relevant part, 42 U.S.C. § 1988 provides that "in any

10

action or proceeding to enforce the provisions of §§ 1981, 1982

1983, 1985 and 1986 of this title, . . . the court, in its

discretion may allow the prevailing party, other than the United

States a reasonable attorneys' fee as part of the cost." Newman v.

Piqqie Park Enterprises, Inc., 308 U.S. 400 (1968). Although §

1988 does not expressly distinguish between plaintiff or defendant,

but rather speaks in terms only of the "prevailing party" the

court, in Christiansburq, 434 U.S. at 419, clearly established the

rule that a defendant is not entitled to the same accomodation as

a prevailing civil rights plaintiff with regard to the award of

attorney fees. For example, in Christiansburq, the Court stated,

"'these policy considerations which support the award of fees to a

prevailing plaintiff are not present in the case of a prevailing

defendant.'" 434 U.S. at 419 (quoting Christiansburq, at 550 F .2d

949, 951 (4th Cir. 1977) .

The Christiansburq rule was developed to favor the

plaintiff in a civil rights action over the defendant because it is

the defendant who is the identified violator of federal "law and who

therefore should bear the responsibility for the plaintiff's

attorney fees when the plaintiff prevails. However, the opposite

is not true. A prevailing defendant cannot suggest that the

plaintiff stands before the court as the violator of federal law,

and, therefore, attorney fees are awarded to the defendant only

"upon a finding that the plaintiff's action was frivolous,

unreasonable or without foundation, even though not brought in

subjective bad faith." Id. 434 U.S. at 421. In passing § 1988,

11

Congress cannot have meant to discourage actions brought on behalf

of minorities, as this action was.

The district court's award of attorneys fees to

intervening defendants pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1988 evolved from

its stance that the Commonwealth was no longer the plaintiff in

this action, but rather "took on the characteristics of a civil

rights defendant for purposes of imposing attorney fees." Opinion

dated Sept. 9, 1991, at p. 15. The district court also

rationalized the award of attorney fees by virtue of the City and

the Commonwealth's role "in creating a need for litigation to

overturn a legally unjustifiable injunction." Id. at p. 16 The

district court acknowledged that . . . "Requiring the original

plaintiff in a civil rights action to pay a portion of the

Intervenors' attorney fees is, perhaps, unprecedented." Opinion

dated August 23, 1993 at p. 7.

This is a legally insufficient basis to warrant the award

of attorney fees against a plaintiff. The Commonwealth initially

prevailed and continued to protect the rights of African Americans

and women from unlawful discrimination through what the district

court itself noted was a persuasive case. The question which the

district court was compelled to decide was not whether the

Commonwealth's position was ultimately successful, but, rather,

whether the lawsuit met the criteria of the Christiansburg rule for

an award of fees against a plaintiff. In Christiansburg the Court

noted:

12

In applying these criteria, it is important

that a district court resist the

understandable temptation to engage in post

hoc reasoning by concluding that, because a

plaintiff did not ultimately prevail, his

action must have been unreasonable or without

foundation. This kind of hindsight logic

could discourage all but the most airtight

claims, for seldom can a prospective plaintiff

be sure of ultimate success. No matter how

honest one's belief that he has been the

victim of discrimination, no matter how

meritorious one's claim may appear at the

outset, the course of litigation is rarely

predictable. Decisive facts may not emerge

until discovery or trial. The law may change

or clarify in the midst of litigation.

434 U.S. at 420.

Indeed, in the Brenner and Dulski fee petition,

particularly at paragraphs 16 and 18, those intervening defendants

asserted a claim for a contingency multiplier because they were

seeking to challenge a preliminary injunction that had been in

place for fifteen years, had not yet resulted in a perfectly

balanced police force, and essentially enjoined the use of the

City's written examination which continued to have some

differential impact across racial and gender groups. "(A - 243).

They further indicated that numerous litigants had attempted to

achieve the results achieved in this case during the past fifteen

years and failed. These representations simply do not establish

the foundation of maintaining any claim that could be construed as

frivolous or unreasonable. These parargraphs also seem to concede

that it was the Commonwealth in this case who was seeking to

enforce a federal law by eliminating the differential impact across

racial and gender lines caused by the City's written examination

13

and also, a balanced police force to remedy the vestiges of past

discrimination.

In this case, the Commonwealth vindicated the

constitutional rights of both African Americans and women and

sought to protect against continuing racial and sex discrimination

in the hiring of City police officers. The district court's

observation that the Commonwealth took on the characteristics of a

civil rights defendant and created a need for litigation by

defending the injunction it obtained flies directly in the face of

both § 19 88 and the Christiansburq rule. The terms of § 19 88

provide that fees may be awarded to the prevailing party in an

action or proceeding to enforce the provisions of § 1981, 1982,

1983, 1985 and 1986 of this title. 42 U.S.C. § 1988. In this

case, in the district court (No. 75-162) it was only the

Commonwealth who initiated an action or proceeding to enforce those

provisions. After that enforcement action, the Commonwealth

obtained an injunction and from that point forward defended the

injunction through various court proceedings that continuously

affirmed the propriety of that injunction. The intervening

defendants were plaintiffs only in civil rights actions to which

the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania was not a party, Nos. 90-457 and

90-629.

This Court's review of the grant of summary judgment

against the Commonwealth and other plaintiffs demonstrates that the

Christiansburq rule for awarding attorneys fees against a plaintiff

has not been met. The court opined that "it is undisputed that

14

dissolution of the preliminary injunction and denial of a permanent

injunction would almost certainly result in a return to white males

predominating on the police force, notwithstanding the City's

vigorous recruitment efforts aimed at minorities and women. 983

F . 2d at 127 2. This Court's conclusion was simply that the

Commonwealth has not met its burden of showing intentional

discrimination and the City's hiring procedures therefore cannot be

said to violate the Constitution. Id. at 1275. This determination

is not the foundation for an award of attorneys fees against a

civil rights plaintiff.

In light of this Court's observation that the award of

attorneys fees against the Commonwealth, a civil rights plaintiff,

was "highly unusual" (983 F .2d at 1275) the Commonwealth filed a

motion for reconsideration. In denying that motion, the district

court acknowledged there is simply no precedent cited to justify an

award of attorneys fees against the Commonwealth under § 1988. See

Opinion dated August 23, 1993 at p. 7. This decision is contrary

to the terms of § 1988 and the controlling Christiansburq rule.

This decision evidences a district court not only failing to resist

the temptation to engage in post hoc reasoning by concluding that

because a plaintiff did not prevail his action must have been

unreasonable or without foundation, but a district court applying

that standard against a plaintiff who in fact has prevailed,

obtained an injunction, and defended that injunction successfully

in appeals to this Court and the United States Supreme Court.

15

Christiansburg, 434 U.S. at 420. Accordingly, the award of

attorneys fees to the intervening defendants should be reversed.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN HOLDING

THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA

LIABLE FOR ATTORNEYS FEES OF THE

INTERVENING DEFENDANTS PURSUANT TO

FED.R.CIV.P. 41(b)

Initially, there is nothing in the language of

Fed.R.Civ.P. 41(b) that provides an award of attorneys fees as "an

appropriate alternative to dismissing this case." (Opinion dated

August 23, 1993 at p. 7). It is the Commonwealth's position that

Rull 41(b) simply does not provide for an award of attorneys fees

against a civil rights plaintiff as was ordered by the district

court.

The sole basis of the district court's opinion of

September 9, 1991 as it relates to attorneys fees was its

application of § 1988. In that opinion the motion to dismiss for

failure to prosecute was denied and the motion for summary judgment

was granted. Further, in its opinion of December 16, 1991 the

district court simply reaffirmed its position with regard to

plaintiff Commonwealth's attorneys fees liability under § 1988.

This Court affirmed the grant of summary judgment and the denial of

the motion to dismiss for failure to prosecute and commented on the

highly unusual action of the district court holding the

Commonwealth liable for fees before dismissing that portion of the

appeal. 983 F.2d 1267, 1275 (3d Cir. 1993).

16

The Commonwealth then filed a motion for reconsideration

based upon this Court's characterization of the Commonwealth's fee

liability. In effectively denying the motion for reconsideration,

the district court affirmed its decision awarding attorneys fees

pursuant to § 1988 against the plaintiff Commonwealth and indicated

that it was relying upon Rule 42 (sic 41)(b) as an alternative to

the drastic action of dismissal of the case for failure to

prosecute. Opinion dated August 23, 1994 at p. 6. This order was

entered after this Court affirmed the denial of the motion to

dismiss for failure to prosecute. The Commonwealth contends that,

because this Court had affirmed the denial of the motion to dismiss

for failure to prosecute, the district court could not subsequently

rely upon Rule 41(b) to impose the sanction of attorneys fees

against the Commonwealth as an alternative to dismissal.

The law of the case doctrine is that once an issue is

decided, it will not be relitigated in the same case, except in

unusual circumstances. Havman Cash Register Co. v. Sarokin, 669

F . 2d 162, 165 (1982). Havman arose in a dispute between judges and

different district courts regarding personal jurisidiction and

venue. In this case, the district court denied the motion to

dismiss for failure to prosecute and this Court affirmed. This

occurred prior to the district court's order of August 23, 1993 in

which the district court directly invoked Rule 41(b). Although the

doctrine of law of the case does not preclude the district court

from clarifying or correcting an earlier ambiguous ruling, the

record is clear that the district court denied the motion to

17

dismiss for failure to prosecute and the record is clear that this

Court affirmed that decision. See Swietlowich v. County of Bucks,

610 F.2d 1157, 1164 (3d Cir. 1979 ). The September 9, 1991 decision

of the district court awarding attorneys fees that the court relies

upon § 1988.

Assuming arguendo, that the district court could have

assessed attorneys fees as an alternative sanction to dismissal

under Rule 41(b) after it denied that motion, the district court

would still be required to comply with the requirements for the

imposition of such a sanction.

The district court did not apply the factors required for

sanctions. See Poulis v. State Farm Fire & Cas. Co., 747 F .2d 863,

868-69 (3d Cir. 1984). Further, under the facts of this case there

is no basis under which such an award would have been authorized.

The Commonwealth complied with all orders of court and presented a

case in defense of the injunction that the district court itself

found to be "persuasive" . There is no consistent violation of time

limits imposed by the court. There is no bad faith. The

determination that the Commonwealth was liable for fees is more

than an abuse of discretion, it is an error of law.

For the above reasons, the order of the district court

relying upon Rule 41(b) to award attorneys fees against the

Commonwealth should be reversed.

18

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the decision of the district

court awarding attorneys fees against the Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania and in favor of the intervening defendants should be

reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

ERNEST D. PREATE, JR.

Attorney General

BY:

THOMAS F. HALLORAN

Senior Deputy Attorney General

CALVIN R. KOONS

Senior Deputuy Attorney General

JOHN G. KNORR, III

Chief Deputy Attorney General

Chief, Litigation Section

OFFICE OF ATTORNEY GENERAL

4TH Floor, Manor Complex

564 Forbes Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

Date: June 3, 1994

19

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA;

GUARDIAN OF GREATER PITTSBURGH

INC.; N .A .A .C.P.; N . O . W . ;

et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

PETER F. FLAHERTY, Mayor,

et al.,

Defendants.

and

F.O.P. for FORT PITT LODGE

No. 1,

Intervening Defendant.

MICHAEL C. SLATER,

Plaintiff,

v .

CITY OF PITTSBURGH,

a municipal corporation,

Defendant.

CHARLES H. BOEHM; PAUL G. CLARK

and RICHARD USNER, on behalf of

themselves and all others

similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

v .

SOPHIE MASLOFF, MAYOR OF THE CITY

OF PITTSBURGH; MELANIE J. SMITH,

DIRECTOR OF PERSONNEL OF THE CITY

OF PITTSBURGH; THE PITTSBURGH

CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION and

THE CITY OF PITTSBURGH,

Defendants.

) •

)

)

)) CIVIL ACTION NO. 75-162

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)) CIVIL ACTION NO. 90-457

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)) CIVIL ACTION NO. 90-629

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

A

OPINION

COHILL, Chief Judge.

Intervenors in Commonwealth v. Flaherty successfully

obtained dissolution of a preliminary injunction requiring race-

and gender-based quota hiring in the Pittsburgh police department.

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania has appealed that ruling.

Intervenors have now moved for an award of attorney's fees, and

also for dismissal for failure to prosecute, or in the alternative,

for summary judgment.

Commonwealth moved to stay consideration of these

motions pending the outcome of its appeal of our decision

dissolving the preliminary injunction. For reasons we explain more

fully below, we denied the motion for stay and scheduled a hearing

for July 24, 1991. Upon agreement of counsel, this hearing

considered only the legal issues presented by the pending motions.

Discovery concerning factual issues was deferred pending our ruling

on the legal issues.

For the following reasons, we will grant the

intervenors' motion for summary judgment and rule that intervenors

may recover attorney's fees from the City and Commonwealth in an

amount to be determined. I.

I. Motion for Stay

An appeal normally divests the district court of

jurisdiction to take further action in the case pending the outcome

of the appeal. Griggs v. Provident Consumer Discount Co. . 459 U.S.

2

56 (1982) (per curiam). But "in an appeal from an order granting

or denying a preliminary injunction, a district court may

nevertheless proceed to determine the action on the merits."

United States v. Price, 688 F.2d 204, 215 (3d Cir. 1982). Since

our March 20, 1991 Order in this case amounted to the denial of a

preliminary injunction, we believe it is appropriate to move ahead

to consideration of the motions for dismissal and for summary

judgment.

As for the petition for attorney fees, the United States

Supreme Court has held that such a petition presents an issue

"uniquely separable" from a decision on the merits. White v. New

Hampshire Deo11 of Employment Sec., 455 U.S. 445, 451-52 (1982).

The Court made it clear that a district court may consider a fee

petition even when a decision on the merits has been appealed. Id.

at 454. In deciding whether to entertain a fee application after

an appeal has been taken, the district court must balance "the

inconvenience and costs of piecemeal review on the one hand and the

danger of denying justice by delay on the other." West v. Keve,

721 F. 2d 91, 95 (3d Cir. 1983). In this case, we believe

consideration of the legal issue of entitlement to attorney's fees

serves the policy of judicial efficiency described by the United

States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit:

Rather than misusing scarce resources, timely filing and

disposition of [certain post-judgment] motions should

conserve judicial energies. In the district court,

resolution of the issue before the inevitable delay of

the appellate process will be more efficient because of

current familiarity with the matter. Similarly,

concurrent consideration of [separately appealed issues]

avoids the invariable demand on two separate appellate

3

panels to acquaint themselves with the underlying facts

and the parties' respective legal positions.

Mary Ann Pensiero, Inc, v. Lingle. 847 F.2d 90, 99 (3d

Cir. 1988) (involving a post-appeal motion for Rule 11

sanctions).

A determination of appropriate fee awards, however, will

require the parties to conduct discovery and the court to engage

in detailed evaluation of fee petitions. This effort would be

wasted if the appeals court were to reverse on the merits. In

addition,

[a] petition for statutory counsel fees routinely

requests payment for relevant services performed during

the whole course of the litigation. There is, thus,

good reason to wait until the lawsuit has been concluded

before calculating the proper fee amount. The

computation of attorney's fees in this context is

frequently a detailed and prolonged undertaking,

requiring thorough review by the trial judge and a

sometimes lengthy hearing.

Id. at 98-99.

We conclude that the interest of judicial economy is

best served by deciding the legal issue of entitlement to fees at

this time (thus facilitating a unitary appeal), while deferring

factual findings on fee amounts until after the merits of the case

have been resolved on appeal. II.

II. Motion to Dismiss for Failure to Prosecute

Intervenors have moved to dismiss this action for

failure to prosecute, or alternatively, for summary judgment. We

will consider the issue of summary judgment in the next section.

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 41(b) provides that

"[f]or failure of the plaintiff to prosecute or to comply with

4

these rules or any order of court, a defendant may move for

dismissal of an action or of any claim against the defendant." The

United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit has warned

that

dismissal in this context is a drastic tool and may be

appropriately invoked only after careful analysis of

several factors, including,

(1) the extent of the party's personal

responsibility; (2) the prejudice to the adversary

caused by the failure to meet the scheduling

orders and respond to discovery; (3) a history of

dilatoriness; (4) whether the conduct of the party

or the attorney was willful or in bad faith; (5)

the effectiveness of sanctions other than

dismissal, which entails an analysis of

alternative sanctions; and (6) the meritoriousness

of the claim or defense.

Dunbar v. Triangle Lumber and Supply Co., 816 F.2d 126,

128 (3d Cir. 1987) (quoting Poulis v. State Farm Fire

and Casualty Co. . 747 F.2d 863, 868 (3d Cir. 1984)

(emphasis omitted).

The basis for the Intervenors1 motion is their

contention that once Judge Weber entered a preliminary injunction

in this action, the plaintiffs, satisfied with their victory, never

moved for a full hearing on the merits or pushed -the Court to

scrutinize the City's attempts to validate its hiring procedures

despite numerous opportunities to do so. They further allege that

the City, content to have the Court dictate its hiring procedures,

never appealed the ruling or sought release from the injunction.

Indeed, as the Intervenors point out, both parties opposed the

intervention of parties seeking to dissolve the injunction.

Intervenors submit that both the plaintiffs and the City knew, or

should have known, that this unspoken arrangement was contrary to

changes in relevant case law, and served to deny intervenors a fair

5

opportunity to seek employment as police officers, free from race

or sex discrimination.

The Commonwealth argues that dismissal would hardly be

appropriate where, as here, the court docket shows activity in this

case for nearly every year since its inception. An examination of

the docket, however, reveals that most of this activity concerned

defense of the injunction from attack, or was related to an aspect

of the case other than hiring. There is no indication that

plaintiffs ever sought further discovery relating to intentional

discrimination or petitioned the Court for a permanent injunction.

Plaintiffs argue further that the preliminary injunction

required the City to validate its hiring procedures, and that the

City has yet to accomplish that directive satisfactorily.

While intervenors1 arguments are not without merit, we

believe dismissal for failure to prosecute would be inappropriate

in this situation. The intervenors suggest that the plaintiffs

should have kept abreast of changes in civil rights law,

anticipated the possible effect these changes could have in

undermining the legal underpinnings of the preliminary injunction,

and comprehended the effect the injunction was having on third

parties. While such action would have been admirable on

plaintiffs' part, we cannot say that their failure to petition the

Court for further action or for a permanent injunction was so

willful or in such bad faith as to justify dismissal.

In addition, Dunbar requires the Court to consider

alternatives to the sanction of dismissal. We will discuss the

6

impact of the City's and Commonwealth's respective roles in this

litigation as part of our consideration of attorney's fees. The

merits of this action will be considered in the next section,

dealing with summary judgment.

Ill. Summary Judgment

Intervenors, as the moving party, bear the burden of

showing that they are entitled to summary judgment. This burden

"may be discharged by 'showing'— that is, pointing out to the

district court— that there is an absence of evidence to support the

nonmoving party's case." Celotex Coro, v. Catrett. 477 U.S. 317,

325 (1986); Chipollini v. Spencer Gifts. Inc.. 814 F.2d 893, 896

(3d Cir. 1987) . In support of their motion, the Intervenors point

out that this Court found no evidence of intentional discrimination

sufficient to support even a preliminary injunction against the

City of Pittsburgh. The City adds that both judges considering the

need for a preliminary injunction took extensive amounts of

evidence, and that if any further evidence of discrimination

existed, it should have already been presented by the Commonwealth.

Plaintiffs argue that they should have the opportunity

to conduct additional discovery and present their full case on the

merits. They contend that evidence presented at the January

hearing on the Intervenors' petition to dissolve the preliminary

injunction raised genuine issues of material fact as to evidence

of intentional discrimination, the validity or invalidity of the

City's hiring procedures, and the existence of vestiges of past

7

unlawful discrimination. They submit that Chipollini warns against

summary judgment when discriminatory intent is an issue in the

case.

In evaluating the Commonwealth's contentions, we note

that "[sjummary judgment procedure is properly regarded not as a

disfavored procedural shortcut, but rather as an integral part of

the Federal Rules as a whole, which are designed 'to secure the

just, speedy and inexpensive determination of every action.'"

Celotex. 477 U.S. at 327 (quoting Fed. R. Civ. P. 1). The

Commonwealth argues that factual disputes between the parties

remain. But "the mere existence of some alleged factual dispute

between the parties will not defeat an otherwise properly supported

motion for summary judgment; the requirement is that there be no

genuine issue of material fact." Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc.

477 U.S. 242, 247-48 (1986) (emphasis in original). The

Commonwealth must show such "sufficient evidence supporting the

claimed factual dispute. . .to require a jury or judge to resolve

the parties' differing version of the truth at trial." First Nat' 1

Bank v. Cities Service Co., 391 U.S. 253, 288-89 (1968). However,

"[i]f the evidence is merely colorable, or is not significantly

probative, summary judgment may be granted." Anderson. 477 U.S.

at 249-250 (citations omitted).

We believe plaintiffs have failed to meet their burden

of showing sufficient evidence of intentional discrimination to

require the time and expense of further evidentiary hearings. As

we noted in our March 20, 1991 Opinion, plaintiffs brought suit

8

under the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981, not Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ("Title VII"). Washington v.

Davis. 426 U.S. 229 (1976), thus requires plaintiffs to show

intentional discrimination on the part of the City before a

judicial remedy is appropriate. Evidence of "vestiges of past

unlawful discrimination" and the invalidity of hiring procedures

are relevant only insofar as they tend to support allegations of

intentional discrimination.

Judge Weber, in his 1975 Opinion establishing the

preliminary injunction, based his determination of race and sex

discrimination not on a finding of intentional discrimination, but

rather on the disparate impact of the City's hiring procedures upon

women and minorities. Pennsylvania v. Flaherty, 404 F. Supp. 1022,

1028-30 (W.D. Pa. 1975). When this Court examined the City's

current hiring methods and its attitude toward the hiring of women

and minorities, we found no evidence of intentional discrimination.

On the contrary, testimony of City officials at our two-day hearing

demonstrated a genuine commitment on the part of the City toward

hiring greater numbers of qualified women and minorities, and

concern over the practical problems the City faced in doing so.

The Commonwealth stipulated that if the injunction were lifted, the

City would continue to "take all reasonable and appropriate steps

to recruit applicants for the position of police officer from all

racial and gender groups, including specifically black and female

applicants." Second Set of Stipulations.

9

Although this is not a Title VII case, this Court in

January nevertheless considered a substanital amount of testimony

about the validation of hiring procedures. We gave careful

consideration to every allowable inference to be drawn from this

testimony and found it showed, at most, that validation of hiring

procedures could have been done with more statistical accuracy.

We found no indication that the City's validation efforts were so

insubstantial that an inference of discriminatory intent could be

drawn. Nor did we find the testimony of the Commonwealth's

witnesses sufficient to support an inference of intentional

discrimination.

We fail to see what evidence plaintiffs would pursue if

this Court were to deny summary judgment and allow further

discovery and yet another evidentiary hearing. Do they hope to

find some "smoking gun" contradicting the City's stated commitment

to affirmative action and unbiased testing of recruits? Do they

believe further examination of the City's testing procedures and

its attempts to validate those procedures will reveal the whole

process as a sham to cover up intentional discrimination? What

other evidence awaits discovery that will present a genuine issue

of past or present intentional discrimination? After 16 years,

discovery of such evidence is unlikely, particularly after the

"extensive stipulation of facts" and the consideration of

"additional evidence" before Judge Weber, and this judge's

examination of a substantial amount of evidence last January.

10

The Commonwealth suggests that summary judgment is

inappropriate when the Court has heard evidence only in

consideration of a preliminary injunction. While this argument

might be effective in the early stages of a fairly new case, the

passage of time and the amount of activity directed toward

determining the existence of intentional discrimination make this

argument untenable. We see no reason to allow plaintiffs to

continue pursuing an obviously insubstantial claim.

Chipollini does not compel a different result. In that

case, the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

overturned a district court grant of summary judgment based on an

absence of direct evidence of discriminatory intent. The appellate

court held that summary judgment was inappropriate when an

inference of discriminatory intent could be drawn from indirect

evidence. 814 F.2d at 900-01. Evidence in the instant case, even

when viewed in the light most favorable to the plaintiffs, "would

be insufficient to carry the [plaintiff]1s burden of proof at

trial." Id. at 896. See also. Healv v. New York Life Ins. Co,, 860

F. 2d 1209, 1218-20 (3d Cir. 1988).

Partial summary judgment will therefore be entered on

plaintiff's claim of discrimination in the hiring of police

officers. As we noted at oral argument, the City remains under an

unchallenged injunction governing the promotion of police officers.

Pennsylvania v. Flaherty, 477 F. Supp. 1263 (W.D. Pa. 1979).

11

IV. Petition for Fees

As mentioned previously, we will rule on the

Intervenors' petitions for attorney fees only as to their

entitlement to those fees.

In an action to enforce certain civil rights provisions

of federal law, "the court, in its discretion, may allow the

prevailing party, other than the United States, a reasonable

attorney's fee as part of the costs." 42 U.S.C. § 1988. The

matter of attorney's fees in this case presents an unusual legal

question. We conclude that the Intervenors are prevailing parties,

since they achieved their objective of dissolving a preliminary

injunction that they claimed unfairly discriminated against white

males. However, they seek to recover fees against a civil rights

plaintiff who won (at least for a time) an injunction on behalf of

women and minorities, and against a defendant that was ultimately

found not to have intentionally discriminated on the basis of race

or sex.

The Supreme Court has adhered to the rule that

prevailing plaintiffs and prevailing defendants receive different

treatment under the civil rights fee provision.

Prevailing plaintiffs in civil rights cases win fee

awards unless 'special circumstances would render such

an award unjust,' Newman v. Piqqie Park Enterprises,

Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 402, 19 L Ed 2d 1263, 88 S Ct 964

(1968) (per curiam), but a prevailing defendant may be

awarded counsel fees only when the plaintiff's

underlying claim is 'frivolous, unreasonable, or

groundless.' Christiansburcr Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434

U.S. 412, 422, 54 L.Ed.2d 648, 98 S Ct 694 (1978).

Roadway Express. Inc, v. Piper. 447 U.S. 752, 762

(1980) .

12

At first glance, it would appear to run counter to the

Supreme Court's holding to award fees against a vindicated

defendant and a plaintiff who has not brought a frivolous or

groundless claim. But "[t]he fee provisions of the civil rights

laws are acutely sensitive to the merits of an action and to

antidiscrimination policy." Id. Looking beyond the party labels

to an examination of the course this case has taken over the years

convinces us that the Intervenors should receive a fee award under

42 U.S.C. § 1988 since they prevailed in the position of a civil

rights plaintiff and there are no "special circumstances [that]

would render such an award unjust." Piggie Park. 390 U.S. at 402.

Intervenors in Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, C.A. 75-

162, are also plaintiffs in their own actions against the City,

Slater, et al. v. City of Pittsburgh. C.A. 90-457, and Boehm, et

al. v. Masloff. C.A. 90-629. They are clearly "prevailing

parties," since their objective— the dissolution of the preliminary

injunction— has been accomplished and since they were the moving

force behind that change. Henslev v. Eckerhart. 461 U.S. 424, 433

(1983) ; Associated Builders & Contractors v. Orleans Parish School

Board. 919 F.2d 374, 378 (5th Cir. 1990). The fact that they

intervened in this action does not diminish their right to receive

a fee award. Donnell v. United States. 682 F.2d 240 (D.C. Cir.

1982) . Nor does the fact that intervenors are non-minorities.

Commons v. Montgomery Ward & Co.. 614 F. Supp. 443 (D. Kan. 1985).

Thus, intervenors should receive a fee award unless special

13

circumstances exist that would render such an award unjust. Pigqie

Park. 390 U.S. at 402.

While the fact that the intervenors seek to recover from

a civil rights plaintiff and a vindicated defendant is an unusual

circumstance, we find that an award of fees in this situation would

not be unjust. As the intervenors argued in their motion to

dismiss for lack of prosecution, the plaintiffs and the City of

Pittsburgh let the issue of hiring lie in a state of legal

dormancy, even after case law undermined the support for the

preliminary injunction, to the prejudice of third parties like the

intervenors. Less than a year after the preliminary injunction

took effect, the Supreme Court announced in Washington v. Davis

that plaintiffs suing under § 1981 must show intentional

discrimination in order to invoke a court's eguitable remedial

powers. Since Judge Weber based his injunction on the disparate

impact of the City's hiring procedures rather than on a finding of

intentional discrimination, the viability of the injunction after

1976 was doubtful. Several years later, the Supreme Court

undermined the rationale for the injunction's separate hiring lists

for men and women. The Court ruled, contrary to Judge Weber's

holding, that the use of veterans preferences in public employment

hiring does not violate egual protection. Personnel Adm'r of Mass,

v. Feeney. 442 U.S. 256 (1979). Yet the Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania, the plaintiff that has carried primary responsibility

in prosecuting this action, never sought a final adjudication on

the merits under the newly announced standards.

14

The Commonwealth argues that under the terms of Judge

Weber's injunction, it was up to the City to establish properly

validated hiring procedures and to prove it had eliminated the

vestiges of past discrimination. But we find no indication that

the Commonwealth ever pressed the Court to address this issue,

despite opportunities to do so. A consulting firm hired by the

City completed validation studies in 1977, 1983 and 1988. While

the Commonwealth now questions these studies, it apparently made

no effort previously to have the Court review the City's efforts

at eliminating discriminatory practices. Intervenors argue that

the Commonwealth, apparently content with its injunction, failed

to move ahead with the case as it should have.

While we have found this pattern of behavior

insufficient to justify the drastic sanction of dismissal, we

believe it removes any claim that the Commonwealth's position as

plaintiff protects it from the imposition of attorney fees. By-

allowing what had become a legally questionable preliminary

•**

injunction to remain the status quo for some 16 years, to the

detriment of third parties' civil rights, the Commonwealth took on

the characteristics of a civil rights defendant for purposes of

imposing attorney fees. We are not persuaded by the Commonwealth's

reliance on Christiansburg Garment, in which the Supreme Court held

that attorney's fees should not be imposed upon civil rights

plaintiffs except "where the action brought is found to be

unreasonable, frivolous, meritless or vexatious." 434 U.S. at 421.

The Supreme Court has clarified that "[t]his distinction [between

15

civil rights plaintiffs and defendants] advances the congressional

purpose to encourage suits by victims of discrimination while

deterring frivolous litigation." Roadway Express. 447 U.S. at 762.

An award of fees in this situation would further the purpose of

encouraging antidiscrimination suits without improperly

contravening the Supreme Court's policy of protecting civil rights

plaintiffs that lose a nonfrivolous case.

The City of Pittsburgh is not entirely blameless,

either, in creating the set of circumstances that required

intervenors to resort to litigation to reverse a discriminatory

injunction. The City never appealed Judge Weber's preliminary

injunction nor asked the Court to re-examine the validity of the

injunction after Davis and Feeney. Intervenors suggest that the

City and Commonwealth in effect colluded to maintain a status quo

that placed the responsibility for dealing with sensitive race and

gender issues with the Court, rather than with bodies accountable

to the voters. We refrain from ascribing such motives to the City

or Commonwealth.

Here we are concerned with effectuating the

congressional goal of encouraging meritorious civil rights

litigation, and the role of the City and Commonwealth in creating

a need for litigation to overturn a legally unjustifiable

injunction. Government bodies have a responsibility to serve the

people fairly, and issues of race and gender discrimination call

for responsible leadership. When a government entity, by action

or inaction, leaves in place a hiring system that unfairly hinders

16

the civil rights of any group, the congressional purpose behind 42

U.S.C. § 1988 justifies the imposition of attorney's fees. The

City's compliance with court orders and its ultimate release from

injunction do not bar the imposition of attorney's fees.

"[L]imiting assessments to those cases where bad faith is shown

unduly narrows the discretion granted to the district judges."

Lieb v. Topstone Industries. Inc.. 788 F.2d 151, 155 (3d Cir.

1986). See also. Martin v. Heckler. 773 F.2d 1145, 1150 (11th

Cir. 1985) (holding that a defendant's "good faith, lack of

culpability, or prompt remedial action [did] not warrant a denial

of fees under the special circumstances preclusion.") The

conclusion we reach today conforms to the Supreme Court's

pronouncements that fees should be awarded so as to further

congressional purposes behind the enactment of fee-shifting

statutes. These include "the general policy that wrongdoers make

whole those whom they have injured" and the policy of "deterring

employers from engaging in discriminatory practices." Independent

Federation of Flioht Attendants v. Zipes, 491 U.S. 754, 762 (1989).

Exercising our discretion under § 1988, we rule that the

Commonwealth should bear 75% of the attorney's fees and the City

25%. We find that the Commonwealth, the chief plaintiff in this

action, bore primary responsibility to prosecute this action

vigorously and in the interests of all racial and gender groups.

While the City complied with court orders and made efforts to

validate its hiring procedures, it should not have been blind to

17

changes in the law and the tendency of the preliminary injunction

to discriminate unfairly under the law.

V. Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, we will bring to a close a

long period of judicial supervision over the hiring of Pittsburgh

police officers. We will grant summary judgment for the City and

the Intervenors on the issue of police hiring, and will reguire the

City and Commonwealth to share the Intervenors' attorney's fees.

A determination of fee amounts, however, will be deferred until the

court of appeals rules on the Commonwealth's pending appeal. There

have been no recent reguests to have the Court address the City's

actions in the area of police promotions. We will therefore direct

the Clerk of Courts to mark this case closed. Any appropriate

party may reopen the case, without an additional fee, upon an

appropriate motion.

An appropriate Order will issue.

Maurice B. cohill, Jr.

Chief Judge

18

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA;

GUARDIAN OF GREATER PITTSBURGH

INC.; N .A .A .C .P.; N . O . W . ;

et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

PETER F. FLAHERTY, Mayor,

et al.,

Defendants.

and

F.O.P. for FORT PITT LODGE

No. 1,

Intervening Defendant.

)

)

)

)) CIVIL ACTION NO. 75-162

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

MICHAEL C. SLATER,

Plaintiff,

v .

CITY OF PITTSBURGH,

a municipal corporation,

Defendant.

)

)

)) CIVIL ACTION NO. 90-457

)

)

)

)

CHARLES H. BOEHM; PAUL G. CLARK

and RICHARD USNER, on behalf of

themselves and all others

similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

v.

SOPHIE MASLOFF, MAYOR OF THE CITY

OF PITTSBURGH; MELANIE J. SMITH,

DIRECTOR OF PERSONNEL OF THE CITY

OF PITTSBURGH; THE PITTSBURGH

CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION and

THE CITY OF PITTSBURGH,

Defendants.

)

)

)

)

)

)) CIVIL ACTION NO. 90-629

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

ORDER

C5 U *:AND NOW, to-wxt, this 7 day of September, 1991, in

accordance with the foregoing Opinion, it is ORDERED, ADJUDGED, and

DECREED that:

1. Intervenors' motions to dismiss for failure to

prosecute be and hereby are DENIED.

2. Intervenors' motions for summary judgment be and

hereby are GRANTED. Summary judgment be and hereby is entered

against the plaintiffs on the issue of police hiring procedures

only.

3. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the City of

Pittsburgh shall be liable for the Intervenors1 attorney's fees in

an amount to be determined and in the following proportion:

Commonwealth, 75%; City, 25%.

4. Further proceedings on attorney's fees be and hereby

are STAYED until further order of this Court.

J k CO* turn. V-

Maurice B. Cohill, Jr.

Chief Judge

cc: Robert B. Smith, Esq.

Joseph F. Quinn, Esg.

Mary K. Conturo, Esq.

City of Pittsburgh

Law Department

313 City-County Building

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

A. Bryan Campbell, Esq.

3100 Grant Building

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

2

Thomas J. Henderson, Esq.

Suite 1002

Law & Finance Building

429 Fourth Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

Robert L. Potter, Esq.

Ronald D. Barber, Esq.

Strassburger, McKenna, Gutnick & Potter

322 Blvd. of the Allies

Pittsburgh, PA 15222

Neighborhood Legal Services

928 Penn Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15222

N.A.A.C.P

2203 Wylie Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

Samuel J. Cordes, Esq.

Philip A. Ignelzi, Esq.

Ogg, Jones, Desimone & Ignelzi

245 Fort Pitt Boulevard

Pittsburgh, PA 15222

Thomas Halloran, Esq.

Manor Building

4th Floor, 564 Forbes Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

Paul D. Boas, Esq.

Berlin, Boas & Isaacson

5th Floor, Law & Finance Bldg.

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

3

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA;

GUARDIAN OF GREATER PITTSBURGH

INC.; N .A .A .C.P.; N .O.W .;

et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

PETER F. FLAHERTY, Mayor,

et al.,

Defendants.

and

F.O.P. for FORT PITT LODGE

No. 1,

Intervening Defendant.

MICHAEL C. SLATER,

Plaintiff,

v .

CITY OF PITTSBURGH,

a municipal corporation,

Defendant.

CHARLES H. BOEHM; PAUL G. CLARK

and RICHARD USNER, on behalf of

themselves and all others

similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

v .

SOPHIE MASLOFF, MAYOR OF THE CITY

OF PITTSBURGH; MELANIE J. SMITH,

DIRECTOR OF PERSONNEL OF THE CITY

OF PITTSBURGH; THE PITTSBURGH

CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION and

THE CITY OF PITTSBURGH,

Defendants.

)

)

)

)) CIVIL ACTION NO. 75-162

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)) CIVIL ACTION NO. 90-457

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)) CIVIL ACTION NO. 90-629

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

B

MEMORANDUM ORDER

Before the Court is the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania's

Motion to Alter or Amend Judgment. For the following reasons, we

will deny the Commonwealth's Motion.

On September 9, 1991, this Court granted intervenor's

motion for partial summary judgment. We held that although the

late Judge Weber and this Court took extensive amounts of evidence,

the plaintiffs failed to meet their burden of showing sufficient

evidence of intentional discrimination to require the time and

expense of further evidentiary hearings. We noted that Judge

Weber, in his 1975 opinion establishing the preliminary injunction

at issue here, based his determination of race and sex

discrimination not on a finding of intentional discrimination, but

rather on the disparate impact of the City's hiring procedures upon

women and minorities.

By our September 9, 1991 Order, we also awarded the

intervenors attorney's fees against the Commonwealth. We held that

although United States Supreme Court held in Christiansburah

Garment Co. v. EEOC. 434 U.S. 412 (1978) and Roadway Express, Inc,

v. Piper. 447 U.S. 752 (1980), that prevailing defendants in civil

rights cases can only obtain attorney's fees if the plaintiff's

claims are frivolous, unreasonable, or groundless, the intervenors

were nonetheless entitled to attorney's fees. We held that by

granting attorney's fees to the intervenors in this case we were

acting consistent with the underlying rationale of the

Christiansburqh opinion. That is, we were acting pursuant to

2

congress' goal of encouraging victims of discrimination to sue

while discouraging frivolous litigation. See Roadway Express. 447

U.S. at 762.

In its Motion to Alter or Amend Judgment, the

Commonwealth argues that this Court erroneously concluded that

there was no genuine issue of material fact. In partial support

of this argument, the Commonwealth points out that we incorrectly

concluded that the Commonwealth stipulated that if the injunction

were dissolved, the City would continue to recruit applicants for

the position of police officer from all racial and gender groups.

In addition, the Commonwealth argues that this Court

misapplied Chipollini v. Spencer Gifts. Inc.. 814 F.2d 893 (3d Cir.

1987) . Chipollini holds that direct evidence of discriminatory

intent is not required to defeat a defendant's motion for summary

judgment and that the plaintiff is entitled to the benefit of all

reasonable inferences to be drawn from the evidence of record and

by resolving disputed issues of fact.

After carefully considering the plaintiff's arguments,

we reaffirm our September 9, 1991 Opinion and Order. Throughout

the course of this litigation, the plaintiffs have not shown

sufficient evidence of intentional discrimination to justify

further evidentiary hearings in this matter. Although we

acknowledge that we erroneously concluded the plaintiffs had

stipulated that the City would continue to take steps to recruit

applicants from all racial and gender groups, we do not find that

this fact affects our decision. We also reaffirm our prior opinion

3

that the intervenors are entitled to attorney's fees and that this

decision is consistent with the rational of the Supreme Court of

the Unites States and the United States Congress. Thus we will

deny the Commonwealth's Motion to Alter or Amend Judgment.

AND NOW, to-wit, this j It ̂ day of December, 1991 it is

ORDERED, ADJUDGED and DECREED that the Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania's Motion to Alter or Amend Judgment be and hereby is

DENIED.

Maurice B. Cohill, Jr.

Chief Judge

cc: Thomas Halloran, Esq.

Manor Building

4th Floor, 564 Forbes Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

Robert B. Smith, Esq.

Joseph F. Quinn, Esq.

Mary K. Conturo, Esq.

City of Pittsburgh

Law Department

313 City-County Building

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

A. Bryan Campbell, Esq.

3100 Grant Building

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

Robert L. Potter, Esq.

Ronald D. Barber, Esq.

Strassburger, McKenna,

Gutnick & Potter

322 Blvd. of the Allies

Pittsburgh, PA 15222

Samuel J. Cordes, Esq.

Philip A. Ignelzi, Esq.

Ogg, Jones, Desimone & Ignelzi

245 Fort Pitt Boulevard

Pittsburgh, PA 15222

4

Mary P. Portis, Esq.

Portis & Associates

Three Gateway Center

Suite 1890

Pittsburgh, PA 15222

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA;

GUARDIANS OF GREATER PITTSBURGH

INC.; N.A.A.C.P.; N .0.W .;

et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

PETER F. FLAHERTY, Mayor,

et al. ,

Defendants.

and

F.O.P. for FORT PITT LODGE

No. 1,

Intervening Defendant.

MICHAEL C. SLATER,

Plaintiff,

v .

CITY OF PITTSBURGH,

a municipal corporation,

Defendant.

CHARLES H. BOEHM; PAUL G. CLARK

and RICHARD USNER, on behalf of

themselves and all others

similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

v .

SOPHIE MASLOFF, MAYOR OF THE CITY

OF PITTSBURGH; MELANIE J. SMITH,

DIRECTOR OF PERSONNEL OF THE CITY

OF PITTSBURGH; THE PITTSBURGH

CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION and

THE CITY OF PITTSBURGH,

Defendants.

)

)

)

)

) CIVIL ACTION NO. 75-162

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

) CIVIL ACTION NO. 90-457

)

)

)

)

)

j

)

)

)) CIVIL ACTION NO. 90-629

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

|0 72A

Pev. 0/82)

c

OPINION

COHILL, D.J.

Before the Court is the Commonwealth's "Motion for

Reconsideration of the Orders of September 9, 1991 and December 16,

1991." The Commonwealth's Motion for Reconsideration applies to

decisions made prior to our granting its motion to withdraw from

the case.

We will grant the Commonwealth's motion to reconsider

but, for the reasons stated below, we decline to reverse our ruling

that the Commonwealth should pay 75% of the Intervenors ' attorney's

fees and that the City should pay 25%.

MOTIONS TO RECONSIDER AWARD OF ATTORNEY'S FEES

By Opinion and Order dated March 20, 1991 this Court-

granted a motion by four white male police officers who intervened

in civil action number 75-162 (Intervenors) to dissolve an

injunction imposing a quota hiring system within the City of

Pittsburgh Police Department. Commonwealth v. Flaherty. 760

F.Supp. 472, (W.D. Pa. 1991). The Injunction and quota system were

imposed in 1975 by the late Judge Gerald Weber as an interim hiring

method to remain in effect until final disposition of the

plaintiff's request for permanent injunctive relief or until

further order of court. Commonwealth v. Flaherty. 404 F.Supp.

1022, 1031 (W.D.Pa. 1975). Fifteen years later this "interim

hiring method" was still in effect.

After they achieved a dissolution of the injunction, the

Intervenors filed a motion to dismiss for lack of prosecution or

2

in the alternative a motion for summary judgement. By Opinion and

Order dated September 10, 1991, we declined to take the drastic

action of dismissal under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 42(b).

We noted, however, that the Commonwealth's inaction permitted the

hiring injunction to continue long after significant changes in

federal law which invalidated the injunction. Therefore we

determined that the Commonwealth should not be insulated from

paying attorney fees under section 1988 simply because it bore the

label of plaintiff. We then granted a petition for fees submitted

by the Intervenors as the prevailing party in the litigation. It

was the Intervenors, after all, who successfully sought and brought

about the dissolution of a preliminary induction requiring race and

gender-based hiring in the Pittsburgh Police Department.

In our Opinion we noted that in an action to enforce

certain civil rights provisions of federal law, "the court, in its

discretion, may allow the prevailing party, other than the United

States, a reasonable attorney's fee as part of the costs."

September 10 Opinion at 12, citing. 42 U.S.Ch § 1988. We

determined that the Intervenors were prevailing parties because

they achieved their objective of dissolving the preliminary

induction which they claimed unfairly discriminated against white

males. We also noted, however, that the Intervenors' request for

fees from the plaintiff and the defendant was unusual.

Prevailing plaintiffs in civil rights cases are awarded

attorney fees unless such an award would be unjust. Prevailing

defendants are awarded attorney fees only when the plaintiff's

3

claim is frivolous, unreasonable or groundless. Id. citing. Roadway

Express, Inc, v. Piper, 447 U.S. 752, 762 (1980). To award

attorney fees to a prevailing intervenor against a civil rights

plaintiff and defendant at first glance would appear to penalize I

a defendant without a finding of liability and would appear to

penalize a plaintiff without a finding that his or her claim was!

frivolous, unreasonable or groundless. We found, however, than

doing so in this case would further the underlying purpose behinc.

awarding attorney fees in civil rights actions, that is,

discouraging discrimination.

We stated that the Intervenors should be treated as