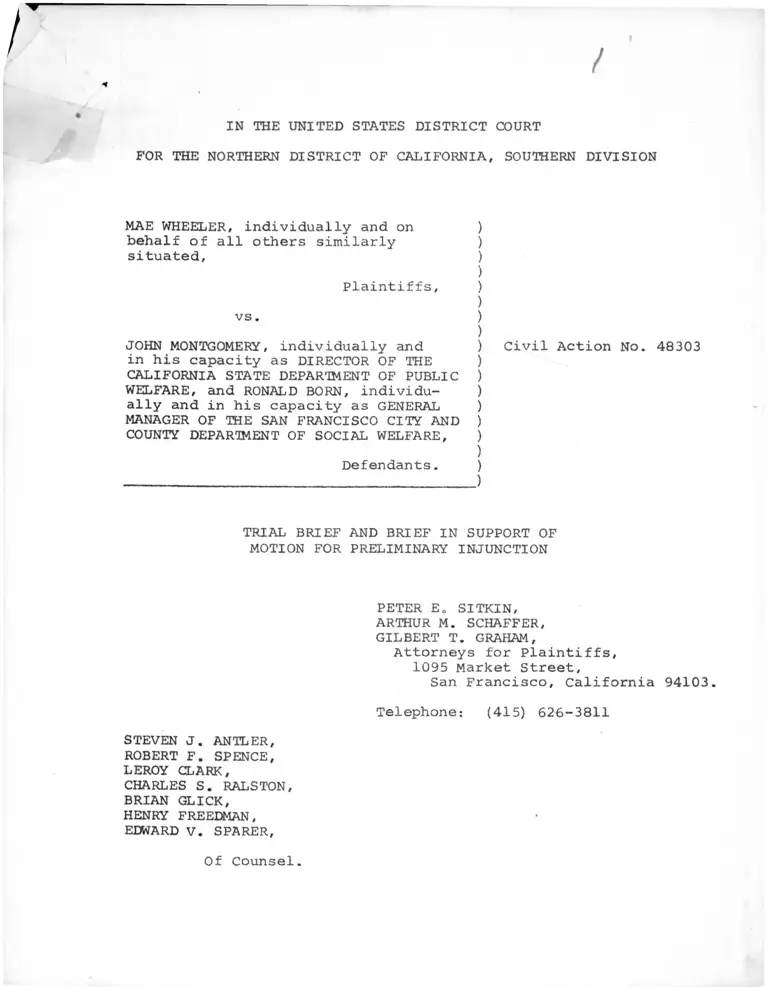

Wheeler v. Montgomery Trial Brief and Brief in Support of Motion for Preliminary Injunction

Public Court Documents

March 15, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wheeler v. Montgomery Trial Brief and Brief in Support of Motion for Preliminary Injunction, 1968. 78107ce6-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0070de0d-0596-4c72-a549-4208c36947c8/wheeler-v-montgomery-trial-brief-and-brief-in-support-of-motion-for-preliminary-injunction. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

/

/

1

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA, SOUTHERN DIVISION

MAE WHEELER, individually and on )

behalf of all others similarly )

situated, )

)Plaintiffs, )

)

vs. )

)JOHN MONTGOMERY, individually and ) Civil Action No. 48303in his capacity as DIRECTOR OF THE )

CALIFORNIA STATE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC )

WELFARE, and RONALD BORN, individu- )ally and in his capacity as GENERAL )

MANAGER OF THE SAN FRANCISCO CITY AND )

COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL WELFARE, )

)Defendants. )

______________________________________________ )

TRIAL BRIEF AND BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF

MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

PETER Eo SITKIN,

ARTHUR M. SCHAFFER,

GILBERT T. GRAHAM,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs,

1095 Market Street,

San Francisco, California 94103.

Telephone: (415) 626-3811

STEVEN J. ANTLER,

ROBERT F. SPENCE,

LEROY CLARK,

CHARLES S. RALSTON,

BRIAN GLICK,

HENRY FREEDMAN,

EDWARD V. SPARER,

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Number

STATEMENT OF THE CASE,..0. » • « o » • « 1

JURISDICTION. 2

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 3

STATEMENT OF FACTS. o • • • • • • 5

ISSUES PRESENTED. 8

STATUTES INVOLVED

POINT ONE

POINT TWO

POINT THREE

OAS RECIPIENTS RECEIVE PUBLIC

ASSISTANCE AS A MATTER OF

STATUTORY RIGHT..................

TERMINATION OF THE GRANTS OF OAS

RECIPIENTS WITHOUT AN OPPORTUNITY

FOR A HEARING PRIOR THERETO VIO

LATES THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE OF

THE FOURTEENTH AMENEMENT........ .

THE TYPE OF HEARING DUE PROCESS

REQUIRES MUST BE DETERMINED WITHIN

THE CONTEXT OF THE SYSTEM IN WHICH IT WILL OPERATE...................

9

10

12

14

A. The specific application of due process

to the welfare system....................... 14

B. The recipient and the welfare system......... 14

C. The fair hearing system.................. .. . ig

D. Due process requires this court to order

that public assistance must be granted

to a recipient who appeals the threat

ened termination of his aid until the

state renders its fair hearing decision..... 18

POINT FOUR - DEFENDANTS' ADOPTED REGULATION DOES

NOT MEET THE MINIMUM STANDARDS OFDUE PROCESS. .... ..................... 2 3

A. Impartial state referee..................... 24

B. Notice.......... ............................ 27

ii

C. Burden of proof..... 28

D. Record...................... 29

E. Confrontation and cross-examination....... 29

F. Defendants are in error in relying on

Thorpe and Dixon to sustain their

regulation................................ 31

1. Thorpe v. Housing Authority,

368 U.S. 670 (1967)................... 31

2. Dixon v. Alabama State Board of

Education, supra...................... 33

POINT FIVE - A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION IS REQUIRED

TO PROTECT THE CLASS OF OAS RECIPIENTS

WHICH PLAINTIFF REPRESENTS FROM

IRREPARABLE INJURY........ . . .......... 3 5

A. Preliminary relief sought................... 35

B. The prerequisites for bringing a classaction have been met...................... 35

C. Preliminary relief should be grantedin the instant case....................... 37

1• Terminated recipients awaiting a

fair hearing decision................. 38

2. Recently terminated recipients.......... 39

3. Future terminations..................... 39

Page

Number

Conclusion 42

ill

Table of Authorities

1. Abrams v. Jones,

35 Idaho 532, 207 Pac. 724 (1922)............. 25

2. Armstrong v. Manzo,

380 U.S. 545, 552 (1965)...................... 20

3. Beard v. Stahr,

370 U„S„ 41 (1962)............................ 28

4. Bell Lines, Inc, v. U.S,,

263 F. Supp. 40 (S.D. W. Va. 1967)............ 29

5. Birnbaum v. Trussel,

371 F.2d 672 (2d Cir. 1966)................... 13

6. Board of Social Welfare v. County of Los Angeles,

27 Cal. 2d 81, 162 P.2d 630 (1945)........... . 10

7. Cole v. Young,

351 U.S. 536 (1956)........................... 13

8. Colletti Travel Service, Inc, v. U.S.,

263 F. Supp. 302 (U.S.D.C. Rhode Island 1966).. 29

9. County of Alameda v. Janssen,

16 Cal. 2d 276 (1940)......................... 10

10. County of Los Angeles v. Frisbee,

19 Cal. 2d 634 (1942)......................... 11

11. County of Los Angeles v, Payne,

8 Cal. 2d 563 (1937).......................... 10

12. County of Sacramento v. Chambers,

33 Cal. App. 142 (1917)......r ............... 10

13. Damico v. California,

88 S. Ct. 526, 19 L. Ed. 2d 647 (1967)........ 2

14. Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education,.

294 F.2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961).................. 3, 16, 33

15. Goldsmith v. Board of Tax Appeals,

270 U.S. 117, 123 (1926)...................... 13

PageNumber

I V

16. Gonzales v. Freeman, 13,

334 F.2d 570 (D.C. Cir. 1964)................. 30

17. Greene v. McElroy, 13,

360 U.S. 474 (1959)........................... 29

18. Henry v. Greenville Airport Comm'n,

284 F.2d 631, 633 (4th Cir. 1960)............. 38

19. Hornsby v. Allen, 13,326 F . 2 d 605 (5th Cir. 1954).................. 30

20. In Re Murchison,349 U.S. 133,' 136, 137 (1955)................. 25

21. Johnson v. Robinson,____ F. Supp. ____-(Civil Action No. 67-C-1883,

N.D. 111., December 29, 196 7).............. . 41

22. Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v, McGrath, 14,

341 U.S. 123, 163............................... 33

23. Kwong Hai Chew v. Colding,

344 U.S. 590, 597-598 (1953)..................... 13

24. Londoner v. Denver,

210 U.S. 373 (1908)............................. 12

25. Mantell v. Dandridge,____ F. Supp. ____ (Civil Action No. 18792,

D. Md. , December 4, 1967).................... 41

26. McNeese v. Board of Education,

373 U.S. 668 (1963)............................. 2

27. Monroe v. Pape,

365 U.S. 167 (1961).........*.............. 2

28. Morgan v. U.S.,

298 U.S. 468 (1936)....................... 14

29. Morgan v. United States,

304 U.S. 1, 18, 19 (1937)..................... 12

Page

Number

V

30. Nash v. Florida Industrial Commission,

____ U.S. ____ (1968) (36 Law Week 4046)...... 21

Page

Number

31. National Labor Relations Board v. Prettyman, 14,

117 F.2d 786 (6th Cir. 1941).................. 27, 29

32. Ohio Bell Telephone v. Public

Utilities Commission,

301 U.S. 292 (1937)........................... 20

33. Ohio Bell Telephone v. Public

Utilities Commission of Ohio, 25,

301 U.S. 292 (1932).................... ....... 29

34. Opp Cotton Mills v. Administrator, 12,

312 U.S. 126 (1941)............................. 33

35. Perry v. Perry, 37,

190 Fo2d 601, 602 (D.C. Cir. 1951).......... . . 38

36. Ramos v. Health and Social Services Board,

(Civil Action No. 67-C-329,

EoD. Wise., November 7, 1967)................ . 40

37 o Ramos v. Health & Social Services Board

of State of Wis.,

276 Fo Supp. 474 (E.D„ Wis. 1967)............. 41

38. Rios v. Hackney,

____ F. Supp. ____ (Civil Action No. CA 3-1852,

N.D. Texas, November 30, 1967).................. 30

39. Slochower v. Board of Education,

350 U.S. 551 (1956)............................. 13

40. Smith v. King,

277 F. Supp. 31, 38 (N.D. Ala* 1967).......... 11

41. Thorpe v. Housing Authority,

368 U.S. 670 (1967).................... ....... 31

42. United States v. Illinois Central R. Co.,'

291 U.S. 457, 463 (1934)...................... 12

VI

43. U.S. v. Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul

and Pacific Railroad Company,

294 U.S. 499 (1935).......................... 29

44. Wasson v. Trowbridge,

382 F .2d 807 (2d Cir. 1967)................... 25

45. Willner v. Committee on Character and Fitness,

373 U.S. 96 (1963)............................ 13

46. Wong Yang Sung v. McGrath,

339 U.S. 33 (1950)............................ 26

47. Wood v. Hoy,266 F.2d 825 (9th Cir. 1959).................. 28

48. Yakus v. United States,

321 U.S. 414, 441 (1944)...................... 37

49. Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer,

103 F. Supp. 569 (D. D.C. 1952), aff'd

(on other grounds) , 343 U.S. 579 (1952)....... 38

50. Zwickler v. Koota, , .

88 S. Ct. 391, 19 L. Ed. 2d 444 (1967)........ 2

Other Authorities

1. Briar, Welfare from Below; Recipients1

Views of the Welfare System, 14,

54 Calif. L . R. 370 (1966)..................... 16

2. Burris, Constitutional Due Process Hearing Require

ments in the Administration of Public Assistance,

16 Am. U.L. Rev. 199, 218 ff.« (1967).......... 23

3. Federal Handbook of Public Assistance 18,

Administration, 25,§ 62 00(3) (d).................................. Appendix

4. Note, Federal Judicial Review of State

Welfare Practices,

67 Colum.L. Rev. 84 (1967)...................... 2

Page

Number

V 1 1

Page

Number

5. Note, Withdrawal of Public Welfare;

The Right to a Prior Hearing,

76 Yale L. J. 1234, 1244 (1967)............... 22

6. Note, 76 Yale L.J. 1242 ......................... 19

7. Reich, Midnight Searches and the

Social Security Act,

72 Yale L.J. 1347, 1359-1360 (1963)........... 15

8. Scholz, Hearings in Public Assistance,

Social Security Bulletin, July 1948 at p. 3.... 18

9. Schottland, The Social Security Program

in the United States,

at page 94 (1963)............................. 11

10. Silver, How to Handle a Welfare Case,

IV Law in Transition Quarterly,94 Fn. 31 (1967).............................. 16

11. Wedemeyer & Moore, The American Welfare System,

54 Calif. L.Ro 326 (1966)..................... 14

♦

1

This is a suit for injunctive and declaratory relief

authorized by Title 42, U„S0C., § 1983, to secure rights, priv

ileges and immunities established by the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States and the Social Security

Act, Title 42, U„S„C., §§ 301, et seq., and the regulations

promulgated thereunder.

The injunctive and declaratory relief sought relates

to the procedure set forth in California Welfare and Institu

tions Code, §§ 12200, 12201 and 10950, et. seq., and the regula

tions promulgated thereunder, on their face and as interpreted

and applied by defendants, wherein financial aid provided to

plaintiff Mae Wheeler and others similarly situated, through

the Old Age Security (OAS) program is terminated without ade

quate and reasonable notice and an opportunity for a prior

hearing which satisfies the standards of due process of law

and the Social Security Act.

This suit was commenced on November 30, 1967. On

December 6, 1967, a temporary restraining order was issued

by Judge Alfonso J. Zirpoli, to avoid irreparable injury to

the named plaintiff, restraining the defendants:

" . . . from enforcing against the plaintiff the pro

visions of Welfare and Institutions Code, Sections 12200, 12201 and 10950, et seq. and the implementing rules and

regulations of the State Department of Social Welfare so

chat Old Age Assistance (OAS) shall be restored to plain

tiff Mae Wheeler forthwith . . . until such time as a

determination is made by this Court regarding plaintiff's

application for convening a Three Judge Court pursuant to

Title 28, U.S.C., §§ 2281 and 2284."

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

2

On December 20, 1967, Judge Zirpoli granted plain

tiff's application for the convening of a three-judge court

to determine the matters herein and also ordered that pursu

ant to Fed. R. Civ. P0 23 (a), (b)(2), (c)(1) and (d)(2):

". o .a class action for declaratory and injunc

tive relief may be maintained, the class to consist of all recipients of old age benefits subject to California

termination statutes."

JURISDICTION

The jurisdiction of this court is invoked under

Title 28 UoS.C. §§ 1343(3) and 1343(4), providing for orig

inal jurisdiction of this court in suits authorized by Title

42 U.S„C. § 1983; jurisdiction is further conferred on this

court by Title 28 U.S.C. §§ 2201 and 2202 relating to decla

ratory judgments. In accordance with Title 28 U.S.C. §§ 2281

and 2284, a three-judge court has been convened to determine

the issues herein. This being an action authorized by Title

42 U.S.C. § 1983, abundant jurisdictional precedent exists.

See, e.g., Zwickler v. Koota, 88 S. Ct. 391, 19 L. Ed. 2d 444

(1967); McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U 0S. 668 (1963);

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961). For a useful review

of the jurisdictional basis, plaintiffs respectfully refer

the court to the Note, Federal Judicial Review of State Welfare

Practices, 67 Colum. L 0 Rev. 84 (1967). The Supreme Court

most recently passed upon the jurisdiction of 'federal courts

in public assistance cases in Damico v. California, 88 S. Ct.

526, 19 L. Ed. 2d 647 (1967).

3

In California a recipient of OAS receives public

assistance as a matter of right. As in the case of plain

tiff Mae Wheeler, an elderly diabetic woman of 75, regular

monthly OAS payments make the difference between subsistence

and starvation. All parties to this action now agree that

opportunity for a hearing must precede termination of public

assistance. At present, the state fair hearing comes well

after termination of aid.

Since the financial assistance provided by OAS is

necessary for recipients to have even minimally adequate

health, care, food and other necessities, the subsequent

hearing— even though it may vindicate the recipient legally—

cannot possibly recompense the recipient for the hunger and

suffering resulting from the termination of aid without a

prior hearing.

The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

requires that the hearing afforded welfare recipients be

adopted to their particular needs. Fortunately, within the

welfare system a hearing designed to provide the elements

of fundamental fairness already exists. This hearing— the

fair hearing— has been developed and refined by the Depart

ment of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) over the past

thirty years.

Defendants have attempted to meet the obvious con

stitutional violation in their procedures by adopting a

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

4

regulation which at best can be interpreted as providing for

an informal prehearing conference. The regulation is wholly

inadequate to the task before it, that is, to provide an OAS

recipient before termination with a hearing at which a fair

determination can be made. Plaintiffs contend that nothing

short of the existing fair hearing, now provided after termi

nation, will meet the minimum standards of due process.

When a vital interest, such as the right to life

or to receive minimum subsistence is at stake, the procedural

safeguards afforded the individual must be great. This is

especially so when viewed in light of the resources and abil

ities of the individuals affected, and when viewed against

the fact that no state interest, other than economy, is

threatened.

Finally, plaintiffs contend that the probability

of success on the merits in this action is sufficiently

strong in light of the serious constitutional violations

already acknowledged to exist by defendants to warrant the

granting of a preliminary injunction.

5

Plaintiff, Mae Wheeler, a 75-year old widow, had

been receiving OAS continuously and in varying amounts since

December 1959, to supplement her Social Security benefits,

currently in the amount of $44.60 per month. Although suffer

ing from a heart condition and diabetes, she lives alone in a

San Francisco Housing Authority apartment. [Defendants'

Exhibit A, p. 3.]

Defendant county received an anonymous telephone

call on August 30, 1967, concerning plaintiff's eligibility

for OAS. Plaintiff was contacted by defendant county on

August 30, 1967, and in that telephone conversation plaintiff

stated that she had received and subsequently transferred

during April 196 7, the proceeds of a check in the sum of

$4,582.15 to her grandson, Bobby Lee Wheeler, in accordance

with her deceased son's deathbed wish. [Pre-Trial Order

(hereinafter sometimes called PTO), p. 5.]

Defendant county discontinued Mrs. Wheeler's OAS

grant effective August 31, 1967. [Defendants' Exhibit A,

p. 2.] During September, October and November 1967, Mrs.

Wheeler did not receive any public assistance. [PTO, p. 5.]

Mrs. Wheeler, with the help of a social worker from

the Public Housing Authority attended numerous conferences

with county welfare personnel to explain the disposition of

the funds she had received and to attempt to have her aid

restored. [Ibid.]

STATEMENT OF FACTS

6

On November 2, 1967, the county, having weighed the

evidence presented, concluded that Mrs. Wheeler's transfer of

her son's insurance was, in fact, to maintain her eligibility

for OAS. The county, therefore, confirmed its discontinuance

of Mrs. Wheeler's OAS and requested repayment of assistance

granted between May 1, 1967 and August 31, 1967. [Defendants'

Exhibit A, p. 4.]

On November 16, 1967, plaintiff filed an appeal

with defendant John Montgomery, Director of the Department

of Social Welfare, and requested a fair hearing, together

with a further request that her aid be restored and continued

pending a decision after said hearing. The hearing was held

on December 22, 1967. [PTO, p. 6.]

On January 12, 1968, defendant John Montgomery

adopted the proposed decision of the hearing officer.

[Defendants' Exhibit A.] The hearing officer concluded that

the county department had erroneously terminated Mrs. Wheeler

as there were no inconsistencies or any other evidence to

contradict the sworn statements of Mrs. Wheeler or her grand

son. He found that Mrs. Wheeler's deceased son owed her

grandson $4,200.00 and that just prior to his death, he had

asked Mrs. Wheeler to repay this debt from the proceeds of

his veteran's insurance policy. Because of this deathbed

request, the hearing officer found that Mrs. Wheeler felt

she had a moral, if not legal, duty to transfer the proceeds

of the insurance policy to her grandson.

7

Defendants' withdrawal and termination of Mrs.

Wheeler's OAS grant caused her immediate and irreparable

injury in that she did not have sufficient funds with which

to subsist on a day-to-day basis without her full OAS grant.

[PTO, p. 5.] All of the actions of the county with respect

to Mrs. Wheeler were taken pursuant to the California Welfare

and Institutions Code and the regulations thereunder. [PTO,

p. 6. ]

In order to receive federal funds for the state

OAS program, California statutes and regulations are required

to confrom to the requirements of the Social Security Act and

the United States Constitution. [PTO, pp. 4-5.] While the

defendant county is authorized to grant financial assistance

under the OAS program, it may do so only in accordance with

the rules and regulations of the State Department of Social

Welfare (hereinafter sometimes called SDSW) which are manda

tory upon all counties. [Declaration of Defendant Born, pp. 2-3.]

If their grants are terminated, OAS recipients have

a right to a fair hearing before state referees who have the

power to rule on the validity and constitutionality of OAS

statutes and regulations. [PTO, pp. 5-7.] However, state

law and regulations do not permit the continuation of assist

ance pending the fair hearing. [Declaration of Defendant

Born, p. 3.] As of January 1968, the average'time from fair

hearing requests to decision was six months. [PTO, p. 7.]

There were, as of December 1967, 13,964 recipients

8

of OAS in San Francisco County. [Plaintiffs' Exhibit 9.]

Mrs. Wheeler was one of 111 OAS recipients in San Francisco

County who were discontinued in 1967 because of increased

personal property holdings. [Plaintiffs' Exhibit 8.] She

was one of 44 San Francisco OAS recipients who requested a

fair hearing in 1967. [Plaintiffs' Exhibit 10.]

During fiscal 1967,* on the average of 285,174 indi

viduals received OAS cash grants monthly in California. The

average monthly amount granted was $101.51. During the year

there were 3,164 requests for fair hearings* of these, 382

requests were filed by OAS recipients; 1,766 requests were

finally determined by fair hearings and 1,279 requests were

resolved by other means. [PTO, pp. 6-7.]

On December 1, 1967, there were 1,210 requests for

fair hearings pending, 116 in the OAS category, including

the request filed by Mrs. Wheeler. [PTO, p. 7.]

ISSUES PRESENTED

The initial issue presented by the litigation is

whether the termination, withdrawal or suspension of the

grants of OAS recipients without an opportunity for adequate

and reasonable notice and a hearing prior thereto violates

the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

*This is the latest period for which the complete sta

tistics are available.

9

Defendants agree with plaintiffs' contention that

due process requires a hearing prior to the termination,

withdrawal or suspension of aid to recipients of the cate

gorical aid programs.

Thus, the ultimate issue for this court is the scope

of the hearing required by the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment and the Social Security Act.

STATUTES INVOLVED

The statutes of the State of California, the appli

cation of which plaintiffs seek to enjoin, are California

Welfare and Institutions Code, §§ 12200, 12201 and 10950,

et seq„, and the regulations adopted thereunder.

10

POINT ONE

OAS RECIPIENTS RECEIVE PUBLIC

ASSISTANCE AS A MATTER OF STATUTORY RIGHT.

Under both federal and California law, a person once

found eligible receives OAS as a matter of right. Pursuant to

the requirements set forth in the Social Security Act, the

California Welfare and Institutions Code states that aid shall

be granted to any eligibile person. [See § 12050.]

In Board of Social Welfare v. County of Los Angeles,

27 Cal. 2d 81, 162 P.2d 630 (1945), the California Supreme

Court held that the county had a mandatory duty to furnish aid

to an individual as of the date of his eligibility for OAS.

A similar result was reached as early as 1914 in Sacramento

Orphans & Children's Home v. Chambers, 25 Cal. App. 536, 144

P. 317 (1914), where it was stated that " . . . the duty of

the state to aid helpless minors is affirmed, or at least

recognized in the California Constitution. . . . " [At p.

543.] In the same case the court further said that " . . .

'welfare appropriations‘ are not to be regarded in light of

charity proceeding." [At p. 544.] See also County of Los

Angeles v. Payne, 8 Cal. 2d 563 (1937) and County of Sacra

mento v. chambers, 33 Cal. App» 142 (1917). California cases

which establish the duty to provide assistance also establish

the correlative right to receive assistance once one is found

to be eligible. See Board of Social Welfare v. Los Angeles

County, supra, at page 86; County of Alameda v. Janseen, 16

11

Cal. 2d 276 (1940) at page 281; County of Los Angeles v.

Frisbee, 19 Cal. 2d 634 (1942) at page 639.

A number of commentaries by Social Security Admin

istration and HEW personnel declare public assistance to be a

statutory right. Charles I. Schottland, a government official,

who was privy to the enactment and effectuation of the statute,

writing in 1963, stated that in all federally-aided public

assistance programs " . . . regular monthly payments are made

to needy persons and such persons have a right to such assist

ance— a right that will be enforced by the courts." Schott

land, The Social Security Program in the United States, at

page 94 (1963) . See also Attmeyer, The Formative Years of

Social Security, at page 58 (1966)„

Recently, a three-judge federal court stated with

respect to the Alabama Aid to Dependent Children program

that:

"As noted earlier, Aid to Dependent Children finan

cial assistance is a statutory entitlement under both

the laws of Alabama and the federal Social Security Act,

and where the child meets the statutory eligibility

requirements he has a right to receive financial bene

fits under the program." Smith v. King, 277 F. Supp.

31, 38 (N.D. Ala. 1967).

Indeed, defendants themselves have conceded that once eligible,

a recipient receives OAS as a matter of statutory right. [PTO,

p. 4, and Deposition, Mr. Frank Vasquez, Chief Referee, SDSW,

at page 28,]

12

POINT TWO

TERMINATION OF THE GRANTS OF OAS RECIPIENTS WITHOUT

AN OPPORTUNITY FOR A HEARING PRIOR THERETO

VIOLATES THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE OF

THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT.

Plaintiffs assert and defendants concede that due

process requires a hearing prior to the termination, with

drawal or suspension of public assistance. [Pre-Trial Order,

p. 23].

The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that where

the individual's essential interests are at stake, final

government action must await an opportunity for a hearing.

The Court met this issue as early as 1908 in Londoner v.

Denver, 210 U.S. 373 (1908), which involved the assessment

of a municipal street improvement tax. The taxpayer had the

right to be heard "before the tax became irrevocably fixed."

210 U.S. at 385. In Opp Cotton Mills v. Administrator, 312

U.S. 126 (1941), the Court, in upholding the application of

the minimum-wage standards of the Fair Labor Standards Act

to a textile manufacturer, stated that due process does "not

require a hearing at the initial stage or at any particular

point . . . in an administrative proceeding so long as the

requisite hearing is held before the final order becomes

effective." 312 U.S. at 152-53. Accord, United States v.

Illinois Central R. Co., 291 U.S. 457, 463 (19.34); Morgan,_v._

United States, 304 U.S. 1, 18-19 (1937) .

More recently the Court has held that due process

13

requires the government to grant opportunity for a hearing

before it terminates a man's employment, Slochower v. Board

of Education, 350 U.S. 551 (1956); Cole v. Young, 351 U.S.

536 (1956); cf. Greene v. McElroy, 360 U.S. 474 (1959);

before it may expel a resident alien, Kwong Hai Chew v^

Colding, 344 U.S. 590, 597-598 (1953) ; before it may deny a

man a license, or certificate of admission, to practice his

profession, Willner v. Committee on Character and Fitne_ss,

373 U.S. 96 (1963); Goldsmith v. Board of Tax Appeals, 270

U.S. 117, 123 (1926). In addition, a number of recent court

of appeals' decisions have required a hearing before an

individual is disbarred from receiving government contracts,

Gonzales v. Freeman, 334 F.2d 570 (D„C. Cir. 1964); before

a student may be expelled from a state university, Dixon, v̂

Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F.2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961),

cert denied, 368 U.S „ 930 (1961); before a municipal hospital

terminates a doctor's employment; Birnbaum v. Trussel, 371

F.2d 672 (2d Cir. 1966); before a liquor license may be

denied. Hornsby v. Allen, 326 F.2d 605 (5th Cir. 1964),

rehearing denied, 330 F. 2d 55 (5th Cir. 1964) 0

14

POTNT THREE

THE TYPE OF HEARING DUE PROCESS REQUIRES MUST

BE DETERMINED WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF THE

SYSTEM IN WHICH IT WILL OPERATE.

A. The specific application of due process to the welfare system.

It is axiomatic that the safeguards embodied in a

due process hearing for welfare recipients can only be deter

mined after careful study of the particular system within

which such a hearing will operate. Joint Anti-Fascist

Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123, 163 (concurring

opinion, Mr. Justice Frankfurter); National Labor Relations

Board v. Prettyman, 117 F.2d 786 (6th Cir. 1941); Morgan v.

U.S., 298 U.S. 468 (1936).

B. The recipient and the welfare system.*

By definition, welfare recipients must be poor.

They are also likely to be uneducated, ignorant of their

legal rights and dependent upon the welfare agency. [Briar,

Welfare from Below: Recipients' Views of the Welfare System,

54 Calif. L.R0 370 (1966).] Although one purpose of public

assistance is to rehabilitate recipients and return them to

*See, generally, Wedemeyer & Moore, The American Welfare

System, 54 Calif. L „R. 326 (1966).

15

the mainstream of society, the welfare system often further

isolates and segregates recipients. As President Lyndon B.

Johnson recently said:

"The welfare system today pleases no one. it is

criticized by liberals and conservatives, by the poor

and the wealthy, by social workers and politicians, by

whites and Negroes in every area of the nation."

[Speech, San Antonio, Texas, January 2, 1968.]

Present laws and regulations require that welfare

department personnel investigate the intimate details of

recipients' lives in order to continually be sure that reci

pients are eligible for the aid they receive. Reich, Midnight

Searches and the Social Security Act, 72 Yale L.J. 1347, 1359-

1360 (1963). When the county department errs it errs by

prematurely terminating aid. In five percent (5%) of the

cases studied by the State Eligibility Control Unit adult

recipients were erroneously terminated. [Eligibility Control

Letter, No. 2064, Plaintiffs' Exhibit 2.] The Control Unit

concluded that assuming their findings were reflective of the

universe of such actions, several thousand recipients had their

grants terminated prematurely. [At p. 1.]

Recipients have one primary remedy to contest

adverse action by the county welfare department — the fair

hearing. However, this remedy is rarely employed. Even

though there were 23,555 OAS recipients terminated for reasons

°ther than death in fiscal 1967, only 382 OAS recipients

filed for hearings. This figure is 1.1 appeals per thousand

active cases. [See State Department of Social Welfare Annual

16

Report, 1966-1967, Table 61, Plaintiffs' Exhibit 4.] Also,

termination is only one of several grounds for appeal.

A number of factors explain why appeals are not very

frequently filed by welfare recipients. Many recipients do

not know about the appeal process. [Briar, supra, at p. 379.]

Appeals take a long time from request to decision. [Welfare

and Institutions Code, §§ 10952, 10958, 10959; Deposition

of Mr. Frank Vasquez, p. 43.] Even when victorious, the claim

ant's aid is only reinstated as of the date the check was

illegally withheld and the county department is not penalized

in any way. [Silver, How to Handle a Welfare Case, IV Law

in Transition Quarterly, 94 Fn. 31 (1967).] Assistance from

lawyers and independent social workers is not available to

most recipients. Another reason for few appeals was suggested

in a recent article:

"Finally, the brutal need of the recipient erro

neously denied assistance will make him all the less

able to pursue the subsequent hearing now available.

Faced with the need to live somehow, he can scarcely

devote the time and energy necessary to effectively

show his continued eligibility on appeal. Because of

this, it is hardly surprising that recipients rarely

even request a hearing after the administrator stops

payments. In Illinois, for instance, appeals were

filed in less than one-third of one percent of the

33,000 public assistance cases closed between July,

1963 and June, 1964 for reasons other than death of

the recipient." Note 76 Yale L.J0 1239, 1244 (1967).

C. The fair hearing system.

Courts, when faced with cases raising the right to

a hearing, have had no established hearing procedure to rely

upon. See, e.g., Dixon, supra. These courts in an attempt

17

to reach a just result have, -therefore, analogized to comparable

situations, balanced the individuals' interests with the inter

ests of the public body or applied equitable doctrines.

In contrast, in the present case, the federal govern

ment has developed, through 30 years1 experience, a hearing

procedure particularly suited to the welfare system. The

special disabilities of welfare recipients and their utter

dependence on the system for their minimum subsistence led to

the development of the procedural rights of the present fair

hearing system,, This system was instituted by HEW in order

to meet the particular needs of public assistance adminis

tration.

HEW's regulations contain the elements of a hearing

which meet the requirements of fundamental fairness. Every

state welfare plan must contain, in part, the following pro

visions:

"l. For specific designation of responsibility within the agency for conduct of hearings,

"2. For rendering decisions that are binding on the State and local agency, and

"3. For establishing hearing procedures to assurethat:

"d. The hearing will be conducted by an im

partial official (or officials) of the State agency.

"g. The claimant has the opportunity (1) to

examine all documents and records used at the hear

ing; (2) at his option, to present his case himself

or with the aid of others, including counsel; (3) to bring witnesses; (4) to establish all pertinent

18

facts and circumstances; (5) to advance any arguments

without undue interference; and (6) to question or refute any testimony or evidence."

(See Appendix attached hereto for the full federal Handbook

of Public Assistance Administration sections governing fair

hearings.)

In 1935, when the Social Security Act went into

effect, there were no precedents for hearings in public assis

tance. The states each drafted their own hearing procedures.

"After 6 years of operation, the Social Security Board issued a set of recommended standards to be used

by State agencies as a guide in clarifying their proce

dures. After 6 more years of observing, comparing,

analyzing and weighing the various procedures developed

by the States, the Social Security Administration issued

a new policy statement on hearings. This release estab

lished definite procedural requirements based on the

experience gained." Scholz, Bernard W., Hearinqs in

Public Assistance, Social Security Bulletin, July 1948, at page 3.

Any termination of aid without the provision of a

hearing embodying the standards of the "fair hearing" is a

sham and a fraud. Given the needs of the terminated welfare

recipients this court should order more safeguards for the

recipients rather than less.

D. Due process requires this court to order that public

assistance must be granted to a recipient who appeals

the threatened termination of his aid until the state renders its fair hearing decision.

Public assistance benefits are calculated to meet

recipients1 minimum needs for living after all other income

is considered. Therefore, during the period of time in which

the recipient is waiting for a hearing decision, he is living

19

below the level which defendants themselves state to be

necessary for survival and decency. Such suffering, danger

ous to the maintenance of life, cannot be remedied once

endured. As noted in a recent Yale Law Journal article:

"The dispositive consideration is that a subsequent

hearing cannot rectify a prior mistake if the needy reci

pient was in fact eligible, and if the state guessed

wrong in terminating or suspending his assistance, he will

have been denied the aid necessary for his basic suste

nance. The requirement in all states that those seeking

public assistance dispose of all their assets in excess

of a stated amount makes this danger all the more real.

"This factor does more than show the stark need the

recipient will face when payments are erroneously denied.

In all cases where he has disposed of assets to become

eligible for assistance, the individual has a strong

reliance claim to a due process hearing before his pay

ments are cut off. The government has induced him to

change his position and has therefore incurred a special

obligation to treat him fairly." 76 Yale L.J. 1242.

In cases involving less compelling interests than

the right to life and minimal subsistence, courts have held

that due process requires a full adjudicatory hearing. Thus,

for example, the Supreme Court, in ruling that a hearing was

required prior to the entry of an order by the Public Utilities

Commission directing a telephone rate refund, stated:

"Regulatory commissions have been invested with

broad powers within the sphere of duty assigned to them by law. Even in Quasi-judicial proceedings their in

formed and expert judgment exacts and receives a proper

deference from courts when it has been reached with due

submission to constitutional restraints. Indeed, much

that they do within the realm of administrative discre

tion is exempt from supervision if those restraints

have been obeyed. All the more insistent is the need,

when power has been bestowed so freely, that the 1inex-

plorable safeguard1 of a fair and open hearing be main

tained in its integrity. The right to such a hearing

20

is one of the rudiments of fair play assured to every

litigant by the 14th Amendment as a minimal requirement.

There can be no compromise on footing of convenience or

expediency, or because of a natural desire to be rid of

harassing delay, when that minimal requirement has been

neglected or ignored." Ohio Bell Telephone Co. v. Public

Utilities Comm., 301 U.S. 292 (1937).

The facts in the instant case demonstrate the import

ance of a fair hearing before aid is terminated. Here, the

county decision to terminate was found to be in error by the

impartial state referee presiding at the fair hearing. In

fact, the hearing officer, in his decision indicated that no

evidence had been presented by the county to support the

termination of Mae Wheeler's aid. Mrs. Wheeler underwent

severe hardships as a result of the termination of her OAS.

Without court intervention, Mrs. Wheeler would, in all proba

bility, still be waiting for a hearing decision. She would

be without her OAS even though she was given an opportunity

to provide the county with evidence of her eligibility at

an informal conference held before a responsible county offi

cial .

As the Supreme Court said in Armstrong v. Manzo,

380 U.S. 545, 552 (1965), the opportunity to be heard ". . .

must be granted at a meaningful time and in a meaningful

manner." California would grant the opportunity for a fair

hearing only after a welfare department had acted to alter

radically the claimant's position vis-a-vis the agency. The

process of appeal makes the claimant sustain more than the

burden of proof, it imposing the burden of life itself.

The Supreme Court recently recognized that a future

21

award of money can mean little to a person of modest means

faced with immediate economic hardship. Nash v. Florida

Industrial Commission, ______ U.S.______(1968) (36 Law Week

4046) .

Since the fair hearing system is already an integral

and required part of welfare administration, the State's re

sistance to continuing aid until the fair hearing decision

appears to be based on economic considerations.* The two

items of increased cost for the State will be additional

referees and hearing expenses and the additional amount of

aid paid to recipients pending the hearing decision.

The major portion of this increased cost will be

borne by the federal government which contributes approxi

mately 50% of the administrative and assistance costs in the

categorical aid program. HEW has specifically stated that

federal financial participation is available to California

if aid payments continue until a fair hearing decision is

rendered. [Letter of St. John Barrett, Deputy General Counsel,

HEW, to Peter E. Sitkin, Plaintiff's Exhibit 1.]

*It should be noted that any hearing before termination

of assistance will cost the State some money. Even the informal

conference provided in the State's regulation will require an

amount of caseworkers' time and, therefore, require the hiring

of additional caseworkers.

22

The State of Mississippi recently proposed a prior

fair hearing system which gives the recipient ten days notice

of the county's intention to terminate. If a recipient requests

a hearing within the ten days, aid will be continued pending

the decision; if no hearing is requested aid will be termina

ted. *

New York State, which holds a large number of fair

hearings, requires that a full fair hearing in cases of sus

pension or discontinuance be held within ten working days from

receipt of the hearing request, and that a decision must be

rendered within 12 working days from the hearing date. [18

NYCRR 84.6, 84.15.] If New York can observe these time limits

then so can California. On this basis if aid were continued,

a recipient would only receive, at most, one additional wel

fare check while awaiting the fair hearing decision. After

reviewing the balance between individual deprivation and the

public purse, one author has concluded:

"Taken together, these considerations compel the

conclusion that the government interest in guarding the

public treasury by postponing hearings should not justi

fy subordination of the private interest in the indivi

dual case, and, _a fortiori, in the totality of cases.

The recipient should have a constitutional right to a

hearing before his welfare payments are discontinued."

Note: Withdrawal of Public Welfare: The Right to a

Prior Hearing, 76 Yale L„J. 1234, 1244 (1967).

♦Memorandum to Mississippi County Welfare Depart

ments. Re: Changes ih Policy on Appeals and Fair Hearings -

Revisions for Public Assistance Manual dated November 15, 1967.

23

POINT FOUR

DEFENDANTS' ADOPTED REGULATION DOES NOT MEET THE

MINIMUM STANDARDS OF DUE PROCESS.

Due process requires that nothing less than the

opportunity for a Social Security Act "fair hearing" be affor

ded OAS recipients before the termination of their grants.

Indeed, an analysis of existing authority indicates that a

compelling constitutional argument can be made for a hearing

which provides a welfare recipient more procedural safeguards

than is presently provided in the "fair hearing." The

authors of a recent article in the American University Law

Review concluded after extensive research that a public

assistance hearing must contain, at a minimum, the following

elements: notice, discovery, right to counsel, oral hearing,

confrontation, cross-examination, impartial tribunal, decision

on the record and judicial review. Constitutional Due Process

Hearing Requirements in the Administration of Public Assist

ance, 16 Am. U.L. Rev. 199, 218 ff. (1967). It has also been

forcefully asserted that a welfare recipient has the right to

a "full trial type hearing." Note: Withdrawal of Public

Welfare: The Right to a Prior Hearing, 76 Yale L.J. 1234,

1239 (1967).

At best, the adopted regulation can be interpreted

to provide only for an informal conference prior to termina

tion. In no event can it be considered to meet minimum due

process standards. The regulation:

24

(a) fails to provide for an impartial state

referee;

(b) does not permit a recipient adequate time to

prepare for the conference;

(c) places the burden of proof on the recipient;

(d) does not require a record or a decision based

upon the evidence adduced at the conference; and

(e) significantly does not provide for confronta

tion and cross-examination.

A. Impartial State Referee.

The adopted regulation provides for an informal

conference before the "caseworker or another responsible

person in the county department."

As has been noted earlier, Mrs. Wheeler was affor

ded an opportunity to have an informal conference with her

caseworker and another responsible person in the county depart

ment (the county appeals officer). Her request for restora

tion was denied even though no evidence contrary to her posi

tion was presented. The informal conference provided in

defendants1 regulation has been offered to terminated OAS

recipients as a matter of general practice in San Francisco.*

Informal conferences (presided over by the very indi

viduals who either made the initial decision to terminate or

*Deposition of Mary Jane Rand discussing the notice and

informal conference provided Mae Wheeler and the fact that

such notice and conference is given as a matter of general

practice, January 15, 1968, pp. 8 to 16.

25

who, in the alternative, will assert the county's position

against the recipient in a subsequent fair hearing) are lack

ing in impartiality. In Wasson v. Trowbridge, 382 F.2d 807

(2d Cir. 1967), the court recognized:

"It is too clear to require argument or citation

that a fair hearing presupposes an impartial trier of

fact and that prior official involvement in a case

renders impartiality most difficult to maintain."(P. 813.]

Due process requires a referee who is not both investigator

and judge, arbiter and advocate in the same cause. Ohio Bell

Telephone v. Public Utilities Commission of Ohio, 301 U.S. 292

<1932)‘ In re Murchison, 349 U.S. 133, 136-137 (1955); Abrams

v. Jones, 35 Idaho 532, 207 Pac. 724 (1922).

This principle of separation of function finds

clear expression in the HEW fair hearing regulations which

require the states to have their hearings conducted by an

impartial official (or officials) of the state agency."

Federal Handbook, § 6200(3)(d). The HEW interpretation of

this section states:

"Impartial official means that the hearing officer has not been involved in any way with the action in

question. Any person who had advised or given consul

tation in any way on the question at issue is disquali

fied as the hearing officer on that case. For example,

a field supervisor who has advised the local agency in

the handling of the case would be disqualified." [§ 6334.]

Similar requirements are placed on all federal administrative

agencies by Section 5(c) of the Administrative Procedure Act.

5 U.SoC0, § 1004 (1964) „ So important is this principle of

separation of function to administrative fairness, that Justice

26

Jackson in Wong Yang Sung v. McGrath, 339 U.S. 33 (1950) said

it was the basic purpose and principal contribution of the

Administrative Procedure Act.

County personnel cannot adequately function as

hearing officers because of the relationship of the counties

to the SDSW. Day-to-day administration of the OAS program is

left to the counties while the policy and regulations are made

at the state level.

County personnel are unable to independently resolve

many issues which arise in fair hearing requests, because they

are obliged to follow the rules and regulations of the SDSW.

[Declaration of Ronald Born, pp. 2-3; see also PTO, p.6.]

For example, see the statement by Mary Jane Rand explaining

that because of Welfare and Institutions Code, § 15001; "The

County could not resolve the issue with our client. There

fore the situation had to go to a Fair Hearing." [Emphasis

added.] [Statement of Mary Jane Rand, enclosed with statis

tics, p. 3, Plaintiffs' Exhibit 10.]

State fair hearing referees, on the other hand, have

the power and authority to rule upon the validity of both

state regulations and statutes. [Deposition of Frank Vasquez,

p. 15) see also PTO, p. 7.] Thus, if a recipient had to

challenge the validity of a statute or regulation asserted

by the county to deny her benefits, she would-be unable to

receive a hearing on such an issue until after termination.

27

B. Notice.

The regulation focuses almost exclusively on the

type of notice given a recipient. Yet, the regulation

utterly fails to provide a reasonable period of time to pre

pare for the hearing.

Davis, in his Treatise on Administrative Law, Vol.

1, § 8.05, states: ”. . . the key to pleading and notice in

the administrative process is adequate opportunity to pre

pare . . . " [At p. 530.] See also N 0L .R„B. v. Prettyman.

--uPr-̂ ' j i i A r _v. American Potash & Chemical Corp., 98 F.2d

488 (9th Cir. 1938); Armstrong v. Manzo. supra.

The regulation provides that a recipient who is to

be terminated will receive at least three days' notice prior

to the withholding of a warrant. PSSM 44-325.43. The regul

ation further provides that the notice shall inform the

recipient, .inter alia, that least one day prior to the with

holding date, an informal conference will be held. Thus,

a recipient must be able to prepare all of the information

required to reestablish eligibility within a period of two

days or have his grant withheld. Not even summary eviction

proceedings usually involving only the issue of nonpayment

of rent are resolved this promptly. Moreover, the recipient

has no time to engage in discovery or review the evidence to

28

be presented against him prior to the informal conference.

Present fair hearing procedure provides the recipient

with at least ten days'notice before the date of the hear

ing. Welfare and Institutions Code § 10952.

C. Burden of Proof.

Contrary to the provisions of the adopted regula

tion, the burden of proof must be on the county to establish

ineligibility. Beard v. Stahr, 370 U.S„ 41 (1962) (dissent

ing opinion); Kwong Hai chew v. Rogers, supra; Wood v. Hoy,

266 F.2d 825 (9th Cir. 1959).

In Beard, supra, the court majority dismissed

the complaint ruling that the case was premature, but

Justices Black and Douglas, dissenting, reached the merits

of plaintiff's contention that an army officer should not

carry the burden of proof in dismissal proceedings and

stated:

"Dismissal is one thing; dismissal with stigma., as here, is quite another,, in comparable situations

the Court has been required to carry the burden of

proof. Unless this burden is meticulously maintained,

discharge for race, for religion, for political

opinion, or for beliefs may masquerade under unproved

charges. This right, like the right to be heard, is

basic to our society." [At p. 43.]

The regulation clearly places the burden of proof

on the recipient to "reestablish eligibility" at the informal

conference even though an OAS recipient, once found eligible,

29

has a statutory right to welfare; the regulation provides that

the withheld warrant will be delivered as soon as there is

eligibility to receive it. [PSSM 44:325.432.] Under the

regulation, on the basis of an _ex parte decision of the

county welfare department, a recipient will be found to be

ineligible and unless the recipient can sustain the burden of

reestablishing eligibility her warrant will be withheld.

D. Record.

Ihe regulation also fails to provide for a record or

for a decision which is supported by the evidence adduced at

the conference. Colletti Travel Service, Inc, v. U.S., 263

F. Supp. 302 (UoS.D.C. Rhode Island, 1966); Ohio Bell Telephone

Co. v. Public Utilities Commission of Ohio, supra; Bell Lines,

Inc, v. U.S., 263 F. Supp. 40 (S„D. W. Va. 1967); U. S„ v.

Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad Company,

294 U.S. 499 (1935) .

Eo Confrontation and Cross-Examination.

A number of recent court decisions establish the

right to confront and cross-examine at administrative hear

ings. Willner v. Committee on Character & Fitness, supra,

p. 103, involving right of confrontation of Bar applicant

by his accussors; Greene v. McElroy, supra, p. 496, involving

right of confrontation by government contractor's employee;

N.L.R.Bo v. Prettyman, supra, p. 70, involving right of

employer to cross-examine witnesses in a National Labor

30

>1

Relations Board hearing,* Gonzales v. Freeman, supra, p. 578,

involving right to cross-examine adverse witnesses in a debar

ment from participating in governmental contracts.

Where a county welfare department had established

its case at a fair hearing solely on the basis of hearsay evi

dence contained in the report of a social worker, a Texas

federal district court reversed the denial of public assist-

ance* £.4p.g. v* Hackney,____F. Supp. _____ (civil Action No.

CA 3-1852, N«,D„ Texas, November 30, 1967) . The court held

as a matter of due process:

The evidence contained in the caseworker's report could not in any manner be relied upon as a basis for

J^yiHg the relief sought in the absence of the plain

tiff s being given an opportunity to cross-examine the

persons who made the statements contained in the report." [Citing Hornsby v. Allen, supra. 1 Slip opinion at p. 3.*

The Rios court also expressly incorporated the due process safe

guards set forth in Hornsby v, Allen into the requirements

for a public assistance fair hearing.

The adopted regulation contemplates only a meeting

with the county welfare personnel and not with the third

parties who provided the information which prompted county

action.

If the recipient meets with "another responsible

person" he will "learn" the information upon which the

county relies only through second or third party hearsay.

The individual facing termination will "discuss the matter

informally," but will be unable to question, confront or

effectively meet the "evidence"

tution requires.

against him as the Consti-

31

Fo D t̂-g-n<̂ an^s are in error in relying on Thorpe and Dixon sustain their regulation.

1* Thorpe v. Housing Authority, 368 U.S. 670

(1967).

Defendants ’ reliance on the Thorpe case is wholly-

misplaced. Mrs. Thorpe had been notified of the termination

of her tenancy by the local public housing authority one day

after she was elected president of a tenant's organization.

Judgment of eviction was obtained on the basis of termination

of the lease although she claimed she had a right to proper

notice of the charges against her and a hearing. While the

case was pending in the United States Supreme Court the U. S.

Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) issued a

binding circular, which led counsel for the tenant to argue

that the judgment of eviction could be reversed, without any

reference to the constitutional issues raised, for failure to

comply with the circular. The Supreme Court stated:

[ T jhe basic procedure [the circular] prescribes

is to be followed in all eviction proceedings that have not become final. if this procedure were accorded to

the petitioner, her case would assume a posture quite

different from the one now presented." [At p. 67 .]

The court then remanded the case to the North Carolina Supreme

Court for a construction of the circular. The state Supreme

Court held the circular not to be applicable to the termina

tion of Mrs. Thorpe’s tenancy, 157 S.E.2d 147 (1967). The

case is again before the Supreme Court, certiorari being

granted on March 5, 1968. [36 L.W. 3346.]

32

The Supreme Court never reached the question of what

minimum notice and hearing standards were required prior to

termination of Mrs. Thorpe's tenancy. it carefully refrained

from any comment on the procedural issues raised and did not

in any way indicate that the HUD requirement would meet due

process standards.

The text of the adopted welfare regulation and the

letter to Judge Zirpoli from Deputy Attorney General Mayers,

dated January 5, 1968, indicate that defendants are attempting

to meet due process with a Thorpe circular-type regulation;

that is, the welfare department, prior to termination, will

tell the recipient of the nature of the information, the

reason for withholding of a warrant, and will discuss the

matter "informally" for purposes of "clarification" and

"possibly resolution." Even assuming, arguendo, that the

Thorpe circular is sufficient in the public housing area,

it will not suffice in the case of the termination of welfare

assistance. When a person is being evicted from public

housing he has a full judicial hearing before the eviction

notice becomes final and he loses his apartment. Regardless

of whether or not he gets a hearing in the Housing Authority,

he gets one in court.

It may be, as was argued in Thorpe, that the court

hearing is limited in scope, but at least issues concerning

the legality of the eviction may be raised. In any event,

the basic standard enunciated by the Supreme Court that a full

hearing must be given somewhere before the decision of the

administrative agency becomes final is pro forma satisfied.

Opp Cotton Mills v. Administrator, supra.

33

2. Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, supra.

The Dixon guidelines, standing alone, appear not to

require a prior state "fair" hearing or the minimum elements

asserted by plaintiffs to be required by due process standards.

However, Fifth Circuit guidelines were established only with

respect to the type of "hearing required prior to the expul

sion from a state college or university." [At p„ 158.] The

court, throughout the opinion, recognizes that its view of

what due process requires is limited to an examination of the

particular "circumstances and interests of the parties in

volved,," [At p. 155.]

The test, indeed the analysis undertaken by the

court, was derived directly from Joint Anti-Fascist Committee

v. McGrath, supra. The Dixon court, after reviewing the cir

cumstances of the case and balancing the interests of the

students and the university, rendered a decision favorable

to the students. When commenting that no "full dress judicial

hearing, with the right to cross-examine witnesses, is

required," the Court specifically states:

"Such a hearing, with the attending publicity and

disturbance of college activities, might be detrimental

to the college's educational atmosphere qnd impractical

to carry out. Nevertheless, the rudiments of an adver

sary proceeding may be preserved without encroaching upon

the interests of the college." [At p. 159.]

34

No state interest, comparable to protecting the educational

atmosphere exists in the instant case and without such a

compelling interest, a full trial-type hearing is required

and would have been required, it is submitted, by the Fifth

Circuit in Dixon.

Finally, in viewing the interests of the students

Dixon and the interest of a recipient such as Mrs. wheeler

who faced irreparable injury as a result of the termination

her welfare grant, it is abundantly clear that greater due

process protection is required in the case of a recipient

facing the loss of her only means of survival than is required

in the case of a student facing the loss of his right to

attend a public educational institution.

Moreover, not even the requirements of Dixon are not

met by the adopted regulation. The regulation provides for

nothing more than an informal conference before the client's

caseworker or other responsible county official. pixon

requires "something more than an administrative interview

with an administrative authority of the college." [At p. 158.]

35

POINT FIVE

A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION IS REQUIRED TO PROTECT

THE CLASS OF OAS RECIPIENTS WHICH PLAINTIFF

REPRESENTS FROM IRREPARABLE INJURY.

A. Preliminary Relief Sought.

Plaintiffs seek at the time of trial a preliminary

injunction ordering defendants, their successors in office,

agents and employees:

(i) to cease immediately from terminating, with

holding, suspending or revoking any OAS recipient's

grant prior to the granting of adequate and reasonable

notice and the opportunity for a hearing which satisfies

the standards of due process of law and the Social Secur

ity Act;

(ii) to notify all recently terminated OAS reci

pients (other than those terminated by reason of death)

that if they believe that their OAS was wrongfully ter

minated that they may request a due process hearing and

that pending the hearing and decision that their OAS will

be restored; and

(iii) to immediately resume OAS payments to all

terminated OAS recipients who have requested a fair

hearing to challenge the termination of their grants and

who are now awaiting final determination of their claims.

B* The Prerequisites For Bringing a Class Action Have Been Met. :

As stated by Judge Zirpoli in his memorandum opinion

36

in the instant case dated December 20, 1967:

"The prayer for declaratory injunctive relief raises

common questions of law for each member of the class;

namely, whether a termination of benefits without a prior

hearing denies a recipient his rights under the United

States Constitution- All members of the class are gov

erned by the same California procedure and statutes.

"The court concludes that the prerequisites of

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(a) are satisfied. Similarly, the

requirement of Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b) is satisfied."

[At p. 5.]

Judge Zirpoli also found that the named plaintiff,

Mae Wheeler, was an adequate representative of the class of

OAS recipients and ". . . that the rights of all members of

the class will be protected without the intervention."

[At p. 6.]

Plaintiffs' claims properly form the basis of a

class action under Rule 23(b)(2) in that the defendants have

acted or refuse to act on grounds generally applicable to the

class. The Advisory Committee Note states that Subdivision

(b)(2) applies when:

" . . . Action or inaction is directed to a class

within the meaning of this subdivision even if it has

taken effect or is threatened only as to one or a few

members of the class, provided it is based on grounds

which have general application to the class. Illustra

tive are various actions in the civil rights field

where a party is charged with discriminating unlawfully

against a class, usually one whose members are incapable

of specific enumeration." [Citations omitted.]

The class herein consists of OAS recipients in

California. Defendants do not contest plaintiffs' assertion

that all OAS recipients are similarly affected by the statutes

and regulations challenged herein. [PTO, pp. 6, 8.] The

latest available statistics indicate that during the year

ending June 1967, there were on the average 285,174 recipi

ents of OAS cash grants monthly.

37

C. Preliminary relief should be granted in the instant case.

Plaintiffs' action raises serious issues of consti

tutional law and there is a substantial possibility that plain

tiffs will prevail upon the merits of this action. Indeed,

defendants have already conceded the validity of one of plain

tiffs' principal contentions.

Plaintiffs bring this action not only to vindicate

their own private rights but in the public interest as well.

First, the constant and vigilant application of federal con

stitutional and statutory standards to state legislation is

£er JL® a matter of the greatest public concern. Second, the

well-being of those of our citizens who are most helpless is

of substantial public interest. Courts have been more liberal

in granting preliminary relief when the public interest is

involved:

"Courts of equity may, and frequently do, go much

further both to give and withhold relief in furtherance

of the public interest than they are accustomed to go

when only private interests are involved." Stone, C.J.,

in Yakus v. United States, 321 U.S. 414, 441 (1944).

The decision to grant a preliminary injunction is

based upon a balancing of many factors:

" . . . the relative importance of the rights asserted

and the acts sought to be enjoined, the irreparable nature

of the injury allegedly flowing from denial of preliminary

relief, the probability of the ultimate success or failure

of the suit, the balancing of damage and convenience gen

erally. . . . " Perry v. Perry, 190 F.2d 601, 602 (D.C. Cir. 1951).

38

iQie stronger the plaintiff's showing of a likeli

hood of ultimately prevailing on the merits, the less of a

showing need he make on the "balancing of the equities."

Perry v. Perry, supra. In Henry v. Greenville Airport Comm'n,

284 F.2d 631, 633 (4th Cir. 1960), the court stated: "The

District Court has no discretion to deny relief by prelimin

ary injunction to a person who clearly establishes by undis

puted evidence that he is being denied a constitutional right."

See also Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 103 F. Supp.

569 (D. D.C. 1952), aff1d (on other grounds) 343 U.S. 579

(1952).

1. Terminated recipients awaiting a fair hearing

decision.

There is no question that the constitutional rights

OAS recipients who are now awaiting fair hearing decisions

have been violated. These OAS recipients did not receive any

hearing before termination. Defendants have conceded that

termination of an OAS recipient's aid without a prior hearing

violates due process.

The immediate reinstatement of all those OAS

recipients who are presently awaiting state fair hearing or

hearings decisions is required. This relief is capable of

practical and expedious enforcement and control. The names

and addresses of such individuals are presently within the

control of the Chief Referee of the State Department of

Social Welfare. [Deposition of Frank Vasquez at page 64.]

39

2. Recently terminated recipients.

Plaintiffs request that all recipients terminated

since the entry of the temporary restraining order in this

case who have not requested fair hearings be notified immedi

ately that if they believe termination to be illegal or

erroneous they may apply for a fair hearing to contest their

termination and that their aid will be reinstated pending a

fair hearing decision. The names and addresses of such indi

viduals are in the possession of each county welfare depart

ment. See, e.g., Deposition of Mary Jane Rand, pages 42-43.

If a hearing were then requested by a terminated recipient,

the State Department of Social Welfare, to whom such a request

would be sent, could direct the appropriate county to restore

the recipient to aid pending the fair hearing decision.

3. Future terminations.

Plaintiffs request a preliminary injunction to pre

vent future terminations under the challenged statutes and

regulations. in terms of interim relief plaintiffs suggest

that the statutes be enjoined to the extent that before ter

mination, recipients be given ten days notice of their right

to request a fair hearing and if such a hearing is requested,

then aid should continue, pending the fair hearing decision.

Such a procedure has recently been proposed for adoption by

the Mississippi Department of Public Welfare._ (Memorandum to

Mississippi County Welfare Departments, supra.)

Plaintiffs have shown irreparable injury to have

40

been caused to the named plaintiff Mae Wheeler and Mrs. Wheeler

has been found to be an adequate representative ofthe class.

The Advisory Committee comments to Civil Practice Rule 23(b)(2)

indicates that action is directed to the class within the mean

ing of the subdivision "even if it has taken effect or is threat

ened only as to one or a few members of the class provided it is

based on grounds which have general application to the class."

This interpretation has been applied on behalf of classes com

posed of welfare recipients by a number of federal courts in

cases involving the public assistance durational residency

requirements.

A three-judge federal court in Wisconsin, after

irreparable injury was shown only with respect to the named

plaintiff, granted a class temporary restraining order pro

hibiting the application of Wisconsin's one-year residency

requirement in categorical public assistance programs. Ramos

v. Health and Social Services Board (Civil Action No. 67-C-329,

E.D. Wise., November 7, 1967). The court stated (Judges Fair-

child, Gordon and Reynolds):

"This Court requires further time for consideration

of the application for preliminary injunction. Plaintiff

Loretta Ramos has no source of income and no financial

resources available to her, and she is unable to sustain

herself and her children. She faces eviction for nonpay

ment of rent. There will be irreparable damage to her and

to her children if defendants continue to deny her assist

ance without determining her eligibility on other grounds.

These facts appear in an affidavit on file and have not

been refuted. There has been no claim that plaintiff is,

in fact, ineligible for any other reason. The number of

applicants denied for lack of one year's residence is

sufficient that there are undoubtedly others in danger of

irreparable injury if no restraining order is issued."

[Emphasis supplied.]

41

Two weeks later a preliminary injunction was granted by the

Ramos court on behalf of the class even though the court noted

that the order would require "disbursing public funds in such

interim with little possibility of recovery in the event the

state ultimately wins." Ramos v. Health & Social Services

Board of State of Wis., 276 F. Supp. 474 (E.D. Wis. 1967).

Similar relief for the class of potential public assistance

recipients has been granted in Johnson v. Robinson, ____ F.

Supp. ____ (Civil Action No. 67-C-1883, N.D. 111., December

29, 1967) and Mantell v. Dandridge, ____ F. Supp. ____ (Civil

Action No. 18792, D.Md., December 4, 1967).

The analogy of these cases to the instant one is

clear. in each, a substantial constitutional question had

been raised. In each, preliminary relief was granted to the

class on the basis of a showing of irreparable injury to the

one individual or a small number of individuals. There was

no need for the plaintiffs in those cases to demonstrate wide

spread irreparable injury; it being assumed that since the

actions of the welfare department apply equally to all recipi

ents and since such action resulted in actual irreparable

injury to named individuals who represented the class, a proper

case for preliminary relief had been made. Furthermore, the

relief was granted in the face of the fact that the interim

order would require the state to dispurse funds without

chance of recovery.

Finally, the court should be aware that plaintiffs

42

attempted to ascertain the names of recently terminated OAS

recipients and/or terminated recipients who are awaiting fair

hearing decisions. Plaintiffs were frustrated in this attempt,

both at the state and county level, by the refusal of defend

ants 1 counsel to make available such information in their

possession on the grounds of confidentiality.

Since no facts are at issue, the preliminary injunc

tion should properly be granted at the time of trial on the

basis of the papers and evidence before the court. The con

tinued infringement of plaintiffs' constitutional rights

should be immediately enjoined to prevent further injury.

Conclusion

For the reasons set forth above, the plaintiffs

respectfully request that the relief requested be granted,

together with such other and further relief as the court

deems just and proper under the circumstances.

Dated: March 15, 1968.

Respectfully submitted,

'1

Peter E„ Sitkin

APPENDIX

6000

Part IV______________________ Eligibility, Assistance, and Services

~36o o-6999" .. Fair Hearings 7/9/5$

Handbook of Public Assistance Administration

6000. Fair Hearings

6l00. Provisions of the Act

Sections 2(a)(k), to2(a)(k), 1002(a) (1*), 1402(a)(4), and l602(a)(k)

read as follows:

"A State plan . . . must . . . provide for granting an opportunity

for a fair hearing before the State agency to any individual whose

claim for (aid or assistance under the plan) is denied or is not

acted upon with reasonable promptness

Section 406(b)(2) authorizes Federal participation in protective payments "but only with respect to a State whose State plan

approved under section iK>2 includes provision for . . .

"(F) opportunity for a fair hearing before the State agency on

the determination (of need for protective payment) for any

individual with respect to whom it Is made

6200. Requirements for State Plans

A State plan under titles I, IV, X, XIV, and XVI must provide:

1. For specific designation of responsibility within the agency

for conduct of hearings,

2. For rendering decisions that are binding on the State and

local agency, and

3 . For establishing hearing procedures to assure that:

a. Every claimant may demand and obtain a hearing before the

State agency in relation to any agency action or failure

to act on his claim with reasonable promptness as defined

in the State plan. (See IV-A-2331, item 1, and IV-2232,

items 2 and 3.)

b. Every claimant is informed in writing at the time of ap

plication and at the time of any agency action affecting his claim, of his right to a fair hearing and of the method

by which he may obtain a hearing.

H.T. No. 56

o200-p.2

Part iv_________ _____________ Eligibility, Assistance, and Services