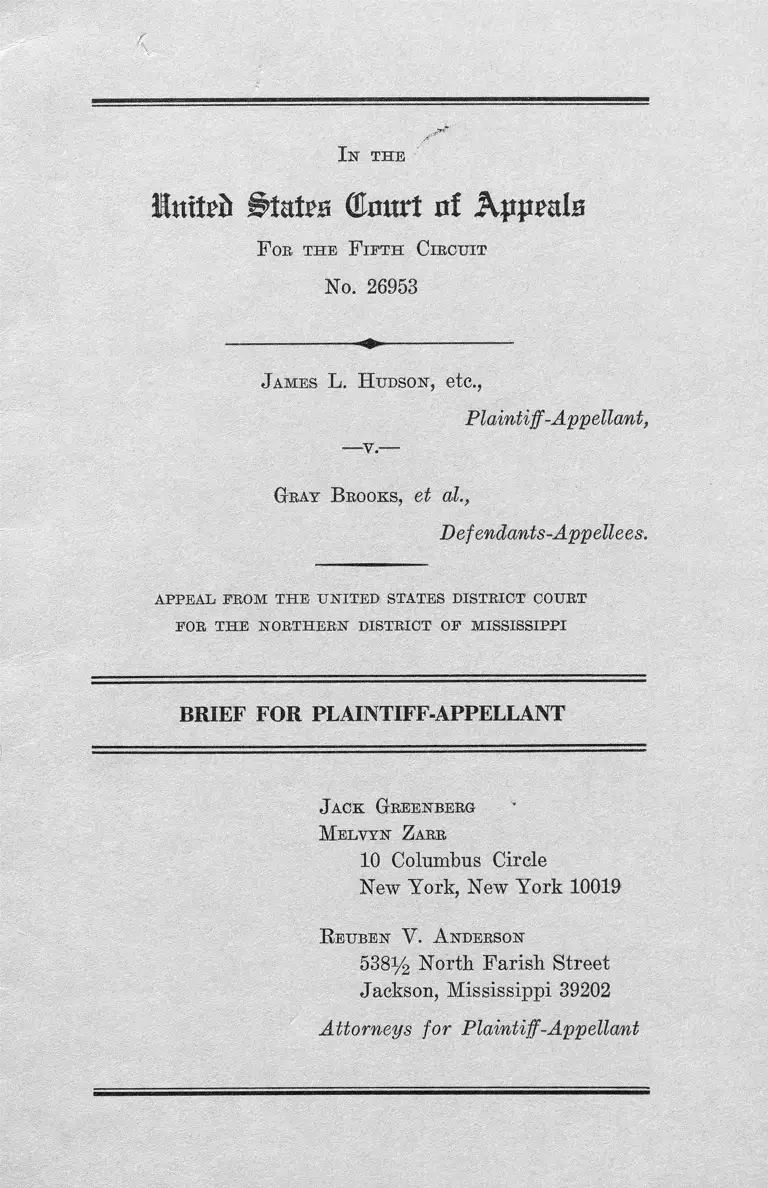

Hudson v. Brooks Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hudson v. Brooks Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant, 1969. 97289191-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/008ae078-48c3-4b6a-8570-e36995030b01/hudson-v-brooks-brief-for-plaintiff-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

luttefc Bintm (Emtrt of Appeals

F ob the F ifth Circuit

No. 26953

I n the

J ames L. H udson, etc.,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Gray Brooks, et at.,

Defendants-Appettees.

APPEAL FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E NO RTH ERN DISTRICT O F M IS SIS SIPP I

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

J ack Greenberg

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Reuben Y. A nderson

538% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

I N D E X

PAGE

Issue Presented............................................................... 1

Statement of the Case................................... ................. 1

Argument

I. Plaintiff Stated a Claim for Relief Under 42

U. S. C. §1985(3) ........................................ 6

II. Plaintiff Stated a Claim for Relief Under 42

U. S. C. §1985(2) ...... 20

Conclusion .......................................................................... 22

T able of Cases

Brewer v. Hoxie School District No. 46, 238 F. 2d 91

(8th Cir. 1956) ........................................................... 18

Bullock v. United States, 265 F. 2d 683 (6th Cir. 1959),

cert, denied, 360 U. S. 909 (1959) ............................. 19

Collins v. Hardyman, 341 IT. S. 651 (1951) ................6, 7, 8

Congress of Racial Equality v. Clemmons, 323 F. 2d

54 (5th Cir. 1963), cert, denied 275 U. S. 992

(1964) ................................................................. 3,9,17,18

Cunningham v. Grenada Municipal Separate School

District, ----- F. Supp. ----- , C. A. No. WC 6633

(1966) 2,3

11

PAGE

Farkas v. Texas Instrument, Inc., 375 F. 2d 629 (5th

Cir. 1967) ............................. ....................................... 9

Jones v. Mayer, 392 U. S. 409 (1968) ....10,12,13,14,17, 21

Kasper v. Brittain, 245 F. 2d 92 (6th Cir. 1957), cert.

denied 355 U. S. 834 (1967) .......... ............................. 19

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U. S. 641 (1966) ................ 17

Mitchell v. Greenough, 100 F. 2d 184 (9th Cir. 1938),

cert, denied 306 U. S. 659 (1939) ................................ 21

Monroe v. Pape, 365 IT. S. 167 (1961) ...........................7,12

Paynes v. Lee, 377 F. 2d 61 (5th Cir. 1967) ............... 7

United States v. Guest, 383 U. S. 745 (1966) ............. 16,17

Van Meter v. Sanford, 152 F. 2d 961 (5th Cir. 1946) .... 21

F ederal S tatutes

Act of April 9, 1866, c. 31, 14 Stat. 2 7 .......... ................ 13

Act of April 20, 1871, c. 22, 17 Stat. 13 .......................10,11

Rev. Stat. §1978 (1874) .................................................. 13

Rev. Stat. §1980 (1874) ... ............................................... 10

18 TJ. S. C. §242 .............................................. 13

28 U. S. C. §1343 ............................................ 3

42 U. S. C. §1982 ............................................. 13

42 U. S. C. §1983 ............................................ 12

42 U. S. C. §1985(2) . Passim

42 U. S. C. §1985(3) ................................. Passim

Other Authorities

p a g e

Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess. (1871) ................... 14,15

Cox, Constitutional Adjudication and Promotion of

Human Eights, 80 Harv. L. Eev. 91 (1966) .............. 16

Note, Federal Civil Action Against Private Individuals

for Crimes Involving Civil Eights, 74 Yale L. J. 1462

(1967) .......................................................................... 15

Eeport of the United States Commission on Civil

Eights, Southern School Desegregation, 1966-67,

pp. 74-108 (July, 1967) ............................................. 20

I n' the

Hmti'ii States Court of Appeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 26953

J ames L. H udson, etc.,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Gray Brooks, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

APPEAL PROM T H E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E NO RTH ERN DISTRICT OF M ISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

Issue Presented

Did plaintiff-appellant sufficiently state a claim for relief

under 42 U. S. C. §§1985(2) and 1985(3)!

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Mississippi dis

missing plaintiff-appellant’s complaint for failure to state

a claimed denial of federal civil rights for which relief

2

could be granted pursuant to 42 U. S. C. §§1985(2) and

1985(3).

The following facts were taken to be true by the court

below in rendering its decision. Plaintiff James Hudson

is a Negro high school student in Grenada, Mississippi who,

prior to the 1966-67 school year, was required by law to

attend a segregated public school (A. 2-3). On July 26,1966,

the court below ordered the Grenada school board to de

segregate and, on August 26, 1966, it accepted the board’s

“freedom of choice” plan (A. 2). Cmmingham v. Grenada

Municipal Separate School District, ----- F. Supp. ——,

Civil Action No. WC 6633. Plaintiff chose to attend the

formerly all-white John Bundle High School and enrolled

on or about September 14, 1966 (A. 2-3).

By November 8, 1966, conditions in the Grenada public

schools had become such as to require the court below to

order the school board to protect Negro children attending

desegregated schools “from violence, intimidation or abuse”

(A. 2). Cunningham v. Grenada Municipal Separate School

District, supra.

On December 9, 1966, in a classroom at the John Bundle

High School, defendant Gray Brooks, a white student, pur

suant to a conspiracy with other white students, threw a

metal object at plaintiff and fractured his skull (A. 3-5).

The purpose of the conspiracy was to injure the plaintiff

and other Negro students for lawfully attempting to enforce

their right to attend a desegregated school and to prevent

and hinder the school board officials from securing to the

plaintiff and other Negro students a desegregated educa

tion (A. 25-26). Because of his injury, plaintiff was forced

3

to withdraw from school for the remainder of the school

year (A. 4).1 2

Plaintiff’s complaint was filed March 30, 1967 by his

mother as next friend against Gray Brooks and his parents,

claiming, inter alia/ a violation of his rights under 42

U. S. C. §1985 (A. 1-6).

Defendants moved to dismiss the complaint on the ground

that no claim for federal relief had been stated.3

On October 2, 1967, (then) District Judge Claude F.

Clayton dismissed the complaint for failure to state a claim

for federal relief holding, inter alia, that plaintiff failed to

state a claim under 42 U. S. C. §1985 because there was

no allegation of state action (A. 22-24). Judge Clayton

granted plaintiff leave to file an amended complaint within

30 days of the order (A. 24-25).

1 Sixty-two Negroes had elected to attend the John Bundle High

School for the 1966-67 school year (together with approximately

650 white students). That number dwindled to 37 by the 1967-

68 school year and to 20 by the 1968-69 school year. Cunningham,

supra.

2 The complaint also claimed violations of rights under the

Fourteenth Amendment and 42 U. S. C. §1983, the federal court

orders in Cunningham, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

and the Mississippi assault and battery statute. A further claim

under 18 U. S. C. §1509 was added by amendment on May 11,

1967 (A. 8-9).

3 Defendants also moved to dismiss on jurisdictional grounds,

claiming that there was neither federal question nor diversity

jurisdiction. Diversity jurisdiction was not invoked by the plain

tiff and the court below correctly found that it had federal question

jurisdiction (A. 16-17). Plaintiff also invoked, and the district

court had, jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C. §1343 (A, 1, 9). Congress

of Racial Equality v. Clemmons, 323 F. 2d 54, 58-60 (5th Cir.

1963), cert, denied 275 U. S. 992 (1964).

4

In an amended complaint filed October 17, 1967, plaintiff

claimed with greater particularity the violation of his rights

under 42 U. S. C. §1985, alleging a conspiracy in violation

of 42 U. S. C. §1985(2) “to injure plaintiff and other Negro

students in their persons and property for lawfully en

forcing and attempting to enforce their rights to the equal

protection of the laws” (A. 25-26) and a conspiracy in vio

lation of 42 U. S. C. §1985(3) to “ [prevent and hinder]

the officials of the Grenada Municipal Separate School

District from giving and securing to plaintiff and other

Negro students the equal protection of the laws, by punish

ing plaintiff and other Negro students for choosing to

attend and attending John Bundle High School and coercing

them to withdraw from that school” (A. 26).* 2 3 4

442 U. S. C. §§1985(2) and 1985(3) provide as follows:

(2) If two or more persons in any State or Territory con

spire to deter, by force, intimidation, or threat, any party or

witness in any court of the United States from attending such

court, or from testifying to any matter pending therein, freely,

fully, and truthfully, or to injure such party or witness in

his person or property on account of his having so attended

or testified, or to influence the verdict, presentment, or indict

ment of any grand or petit juror in any such court, or to in

jure such juror in his person or property on account of any

verdict, presentment, or indictment lawfully assented to by

him, or of his being or having been such juror; or if two or

more persons conspire for the purpose of impeding, hindering,

obstructing, or defeating, in any manner, the due course of

justice in any State or Territory, with intent to deny to any

citizen the equal protection of the laws, or to injure him or

his property for lawfully enforcing, or attempting to enforce,

the right of any person, or class of persons, to the equal pro

tection of the laws;

(3) If two or more persons in any State or Territory con

spire or go in disguise on the highway or on the premises of

another, for the purpose of depriving, either directly or in

directly, any person or class of persons of the equal protection

of the laws, or of equal privileges and immunities under the

laws; or for the purpose of preventing or hindering the con

stituted authorities of any State or Territory from giving or

5

Defendants again moved to dismiss for failure to state

a claim for federal relief (A. 27).

Circuit Judge Clayton having become physically disabled,

the case was reassigned to District Judge William C. Keady

who, on October 2, 1968, dismissed the complaint as

amended “for jurisdictional failure to state a claim upon

which relief can be granted” (A. 31-32). Judge Keady

agreed with Judge Clayton “that there exists no such an

cillary right as that asserted here to money damages from

an individual, absent any claim of state action of any kind”

(A. 31).

Plaintiff’s timely appeal to this Court followed (A. 32).

securing to all persons within such State or Territory the

equal protection of the laws; or if two or more persons con

spire to prevent by force, intimidation, or threat, any citizen

who is lawfully entitled to vote, from giving his support or

advocacy in a legal manner, toward or in favor of the election

of any lawfully qualified person as an elector for President

or Vice President, or as a Member of Congress of the United

States; or to injure any citizen in person or property on ac

count of such support or advocacy; in any case of conspiracy

set forth in this section, if one or more persons engaged therein

do, or cause to be done, any act in furtherance of the object

of such conspiracy, whereby another is injured in his person

or property, or deprived of having and exercising any right

or privilege of a citizen of the United States, the party so

injured or deprived may have an action for the recovery of

damages, occasioned by such injury or deprivation, against any

one or more of the conspirators.

6

A R G U M E N T

I.

Plaintiff Stated a Claim for R elief Under 42 U. S. C.

§ 1 9 8 5 (3 ) .

As analyzed by the Supreme Court of the United States

in Collins v. Hardyman, 341 U. S. 651, 660 (1951), 42 U. S. C.

§1985(3) proscribes each of the following four classes of

conspiracies:

(1) For the purpose of depriving any person or class

of persons of the equal protection of the laws, or of

equal privileges and immunities under the law; or

(2) For the purpose of preventing or hindering the

constituted authorities from giving or securing to all

persons the equal protection of the laws; or

(3) To prevent by force, intimidation, or threat, any

citizen entitled to vote from giving his support or

advocacy in a legal manner toward election of an elector

for President or a member of Congress; or

(4) To injure any citizen in person or property on

account of such support or advocacy.

Collins v. Hardyman dealt solely with an alleged con

spiracy of the first class. There, the plaintiffs’ political

club meeting was broken up by a gang of toughs; the inci

dent giving rise to the suit was characterized by the Su

preme Court as “a lawless political brawl, precipitated by

a handful of white citizens against other white citizens”

(341 U. S. at 662). The plaintiffs claimed a denial of their

“equal privileges and immunities under the laws” ; for all

7

that appears, they did not claim a denial of equal protec

tion of the laws (341 U. S. at 654-55). The Supreme Court

held that the complaint failed to sufficiently state a claim

for relief under §1985(3) because it lacked the essential

allegation of the denial of a right to equality, stating (341

IT. S. at 661):

The only inequality suggested is that the defendants

broke up plaintiff’s meeting and did not break up meet

ings of others with whose sentiments they agreed. To

be sure, this is not equal injury, but it is no more a

deprivation of ‘equal protection’ or of ‘equal privileges

and immunities’ than it would be for one to assault one

neighbor without assaulting them all, or to libel some

persons without mention of others.5 6

A conspiracy involving class 3 or 4, i.e., involving fed

erally protected voting rights, was before this Court in

Paynes v. Lee, 377 F. 2d 61 (5th Cir. 1967).6

This case involves a conspiracy of class 2.

5 In dictum, the Court went on to say that, even if a right to

equality had been alleged, it would have had to be of massive pro

portions (341 U. S. at 662) :

We do not say that no conspiracy by private individuals

could be of such magnitude and effect as to work a depriva

tion of equal protection of the laws, or of equal privileges

and immunities under laws. Indeed, the post-civil war Ku

Klux Klan, against which this Act was fashioned, may have,

or may reasonably have been thought to have, done so.

Whatever the validity of this dictum as to a class 1 conspiracy,

its implied limitation cannot properly be imposed upon a class 2

conspiracy. See Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167, 200, note 9 (1961)

(concurring opinion of Justices Harlan and Stewart). See also

note 12, infra.

6 In dictum, this Court stated (377 F. 2d at 63) :

The denial of a Federal remedy against persons not acting

under color of state law is only in cases where the asserted

8

Plaintiff alleged that the conspiracy was “for the pur

pose of preventing and hindering the officials of the Grenada

Municipal Separate School District from giving and se

curing to plaintiff and other Negro students the equal

protection of the laws, by punishing plaintiff and other

Negro students for choosing to attend and attending John

Bundle High School and coercing them to withdraw from

that school” (A. 26).

Since the constituted school authorities had elected to

employ the “freedom of choice” method of desegregation,

and since the alleged conspiracy was utterly destructive of

free choice and of desegregation, plaintiff clearly appeared

to allege a class 2 conspiracy. Put another way, plaintiff

clearly appeared to state a claim under the following pro

vision of §1985(3):

If two or more persons in any State or Territory

conspire or go in disguise on the highway or on the.

premises of another . . . for the purpose of preventing

or hindering the constituted authorities of any State

or Territory from giving or securing to all persons

within such state or territory the equal protection of

the laws . . . ; in any case of conspiracy set forth in

this section, if one or more persons engaged therein

do, or cause to be done, any act in furtherance of the

object of such conspiracy, whereby another is injured

in his person or property, or deprived of having and

right stems from the Fourteenth Amendment and the claim

is for damages resulting from an abridgment of privileges or

immunities or a denial of equal protection of the laws. Such

was the case of Collins v. Hardyman, supra.

For reasons previously stated, this is not a correct statement of

Collins v. Hardyman, nor, for reasons hereinafter to he developed,

is it a correct statement of the law.

9

exercising any right or privilege of a citizen of the

United States, the party so injured or deprived may

have an action for the recovery of damages, occasioned

by such injury or deprivation, against any one or more

of the conspirators.

However, the court below ruled otherwise, holding that

a claim under §1985(3) could not be stated absent an

allegation of state action (A. 22-23, 31). The court below

relied upon the following language from this Court’s alter

native holding in Congress of Racial Equality v. Clem

mons, 323 F. 2d 54, 62 (5th Cir. 1963), cert, denied 275

U. S. 992 (1964):

A fatal third weakness in the plaintiffs’ case is that

the defendants are private persons. It is still the law

that the Fourteenth Amendment and the statutes en

acted pursuant to it, including 42 U. S. C. A. §1985,

apply only when there is state action. Collins v. Hardy-

man.1

Plaintiff submits that this language from the alternative

holding in Congress of Racial Equality v. Clemmons is not

a correct statement of the law insofar as it refers to a

conspiracy of class 2 under §1985(3). Specifically plaintiff

submits:

1. On its face, the invoked portion of §1985(3) reaches

conspiracies by private individuals, absent any claim of

state action; 7

7 This language was repeated in Farkas v. Texas Instrument,

Inc., 375 F. 2d 629, 634 (5th Cir. 1967), also cited by the court

below (A. 23). Farkas claimed a conspiracy of the first class,

alleging that his former employer and a potential employer had

conspired to deny him employment because of his national origin.

1 0

2. Congress meant what it said;

3. Congress had the power under §5 of the Fourteenth

Amendment to enact it, as construed;

4. The 'principal holding of Congress of Racial Equality

v. Clemmons supports plaintiff’s right to relief; and,

5. “The fact that the statute lay partially dormant for

many years cannot be held to diminish its force today”

{Jones v. Mayer, 392 U. S. 409, 437 (1968)).

Jones v. Mayer, 392 U. S. 409 (1968), teaches that courts

must be extremely hesitant to find an implied limitation on

federal civil rights legislation where none appears on its

face. On its face, the invoked provision of §1985(3) is not

limited to conspiracies in which officials participate. In

deed, to be blunt, such a reading makes little sense. State

officials skulking along the highway to harass other state

officials cannot have been the sole concern and object of

this legislation. Nor was it.

§1985(3) was enacted as part of the Ku Klux Act of

1871. Act of April 20, 1871, c. 22, 17 Stat. 13; codified

as §1980(3) of the Revised Statutes of 1874. The Ku Klux

Act, as its name implies, was enacted in reaction to the

wave of Klan terror sweeping the South. See, e.g., Jones

v. Mayer, supra, 392 TJ. S. at 435.

The structure of the Ku Klux Act is crucial to its con

struction. §1985(3) was enacted as part of §2 of the Ku

Klux Act.8 Section 1 of that Act, which became the present

8 §2 provided, in relevant p a r t:

That if two or more persons within any State or Territory

of the United States shall conspire together . . . by force, in-

11

42 U. S. C. §1983, specifically proscribed conduct taken

“under color of law.” 9 The comparison is extremely sig-

timidation, or threat to deter any party or witness in any

court of the United States from attending such court, or from

testifying in any matter pending in such court fully, freely,

and truthfully, or to injure any such party or witness in his

person or property on account of his having so attended or

testified, or by force, intimidation, or threat to influence the

verdict, presentment, or indictment, of any juror or grand

juror in any court of the United States, or to injure such

juror in his person or property on account of any verdict,

presentment, or indictment lawfully assented to by him, or on

account of his being or having been such juror, or shall con

spire together, or go in disguise upon the public highway or

upon the premises of another for the purpose, either directly

or indirectly, of depriving any person or any class of persons

of the equal protection of the laws, or of equal privileges or

immunities under the laws, or for the purpose of preventing

or hindering the constituted authorities of any State from

giving or securing to all persons within such State the equal

protection of the laws, or shall eonspire together for the pur

pose of in any manner impeding, hindering, obstructing, or

defeating the due course of justice in any State or Territory,

with intent to deny to any citizen of the United States the

due and equal protection of the laws, or to injure any person

in his person or his property for lawfully enforcing the right

of any person or class of persons to the equal protection of

the laws, or by force, intimidation, or threat to prevent any

citizen of the United States lawfully entitled to vote from giv

ing his support or advocacy in a lawful manner towards or

in favor of the election of any lawfully qualified person as an

elector of President or Vice-President of the United States,

or as a member of the Congress of the United States, or to

injure any such citizen in his person or property on account

of such support or advocacy. . . . And if any one or more

persons engaged in any such conspiracy shall do, or cause to

be done, any act in furtherance of the object of such con

spiracy, whereby any person shall be injured in his person

or property, or deprived of having and exercising any right

or privilege of a citizen of the United States, the person so

injured or deprived of such rights and privileges may have

and maintain an action for the recovery of damages occasioned

by such injury or deprivation of rights and privileges against

any one or more of the persons engaged in such conspiracy.

9 §1 provided:

That any person who, under color of any law, statute, ordi

nance, regulation, custom, or usage of any State, shall subject,

1 2

nificant: when Congress intended to limit civil rights

legislation to deal only with conduct under color of state

law, it did so in unmistakable terms.

In comparing §§1 and 2 of the Ku Klux Act of 1871,

Justices Harlan and Stewart, concurring in Monroe v.

Pape, 365 U. S. 167, 200 (1961), expressed their belief that

a class 2 conspiracy can encompass wholly private action:

Indeed it is difficult to attribute to a Congress which

forbade two private citizens from hindering an offi

cial’s giving of equal protection an intent to leave that

official free to deny equal protection of his own ac

cord.7

7 Compare the statement of Representative Burchard:

“If the refusal of a State officer, acting for the State, to

accord equality of civil rights renders him amenable to pun

ishment for the offense under United States law, conspirators

who attempt to prevent such officers from performing such

duty are also clearly liable.” Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess.

App. 315.

This conclusion is made inescapable by the Supreme

Court’s decision in Jones v. Mayer, supra. There, the

or cause to be subjected, any person within the jurisdiction

of the United States to the deprivation of any rights, privi

leges, or immunities secured by the Constitution of the United

States, shall, any such law, statute, ordinance, regulation,

custom, or usage of the State to the contrary notwithstanding,

be liable to the party injured in any action at law, suit in

equity, or other proper proceeding for redress . . .

Present §1983 provides:

Every person -who, under color of any statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory, sub

jects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United

States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the

deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by

the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured

in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding

for redress.

13

Court was called upon to construe 42 U. S. C. §1982/°

which had been enacted as part of §1 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1866. Act of April 9, 1866, c. 31, §1, 14 Stat. 27,

re-enacted by §18 of the Act of May 31, 1870, c. 114, §18,

16 Stat. 140, 144; codified in §§1977 and 1978 of the Re

vised Statutes of 1874. There was no limitation to govern

mental action on the face of §1982, and the Court held that

none was to be implied (392 U. S. at 420-436). This con

clusion was held compelled by the fact that §2 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1866, which became 18 U. S. C. §242,“ ex

plicitly contained a “color of law” requirement. The Court

held: “Indeed, if §1 had been intended to grant nothing

more than an immunity from governmental interference,

then much of §2 would have made no sense at all” (392

U. S. at 424). (Emphasis Court’s). The Court continued;

“Hence the structure of the 1866 Act, as well as its lan

guage, points to the conclusion urged by the petitioners

in this case—that §1 was meant to prohibit all racially

motivated deprivations of the rights enumerated in the

statute, although only those deprivations perpetrated ‘un- 10 11

10 §1982 provides:

All citizens of the United States shall have the same right,

in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by white citizens

thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real

and personal property.

11 §242 provides:

Whoever, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regula

tion, or custom, willfully subjects any inhabitant of any State,

Territory, or District to the deprivation of any rights, privi

leges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution

or laws of the United States, or to different punishments,

pains, or penalties, on account of such inhabitant being an

alien, or by reason of his color, or race, than are prescribed

for the punishment of citizens, shall be fined not more than

$1,000 or imprisoned not more than one year, or both. . . .

14

der color of law’ were to be criminally punishable under

§2” (392 U. S. at 426) (Emphasis Court’s).

The relevant legislative history supports the conclusion

that Congress intended to reach nongovernmental con

duct. The Act was entitled “An Act to Enforce the Pro

visions of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, and for Other Purposes.” As origi

nally introduced, §1985(3) was not limited to protect sim

ply rights to equality. Accordingly, it was complained that

the provision, as drafted, would subvert the entire criminal

jurisdiction of the States. In order to meet this criticism,

the provision was amended to protect only rights to equal

ity. Representative Shellabarger, the floor leader, ex

plained the amendment in these terms (Cong. Globe, 42nd

Cong., 1st Sess., 478 (1871)) :

The object of the amendment is . . . to confine the au

thority of this law to the prevention of deprivations

which attack the equality of rights of American citi

zens; that any violation of the right, the animus and

effect of which is to strike down the citizen, to the end

that he may not enjoy equality of rights as contrasted

with his and other citizens’ rights shall be within the

scope of the remedies of this section.

This amendment satisfied an earlier critic, Representa

tive Poland, who endorsed the amended bill in these terms

(Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 1st Sess., 514 (1871)):

But I do agree that if a State shall deny the equal

protection of the laws, or if a State make proper laws

and have proper officers to enforce those laws, and

somebody undertakes to step in and clog justice by

preventing the State authorities from carrying out this

constitutional provision, then I do claim that we have

the right to make such interference an offense against

the United States; that the Constitution does empower

us to aid in carrying out this injunction, which, by

the Constitution, we have laid upon the States, that

they shall afford the equal protection of the laws to

all their citizens. When the State has provided the

law, and has provided the officer to carry out the law,

then we have the right to say that anybody who under

takes to interfere and prevent the execution of that

State law is amenable to this provision of the Con

stitution, and to the law that we may make under

it declaring it to be an offense against the United

States.12

This amendment also satisfied a majority of Congress.

The legislative debates are traced in Note, Federal Civil

Action Against Private Individuals for Crimes Involving

Civil Bights, 74 Yale L. J. 1462, 1467-70 (1965). The Note

concludes that “Congress wished to act to the full extent

of its constitutional power [under §5 of the Fourteenth

12 An opponent of the provision was, if anything, even clearer

in expressing his understanding of the coverage of the provision:

. . . It does not requii'e that the combination shall be one

that the State cannot put down; it does not require that it

shall amount to anything like insurrection. If three persons

combine for the purpose of preventing or hindering the con

stituted authorities of any State from extending to all persons

the equal protection of the laws, although those persons may

be taken by the first sheriff who can catch them or the first

constable, although every citizen in the country may be ready

to aid as a posse, yet this statute applies. It is no case of

domestic violence, no case of insurrection, and no case, there

fore, for the interference of the Federal Government, much

less its interference where there is no call made upon it by the

Governor or the Legislature of the State. Id, at App 218

(Senator Thurman); see also id, at 514 (Rep Farnsworth).

16

Amendment] in order to satisfy the Radical Republicans.”

(Id. at 1469.)

Any doubt as to the constitutional power of Congress to

do what it did in enacting §1985(3) has been dispelled by

the statement of views of Mr. Justice Brennan, speaking

for 6 members of the Court, in United States v. Guest,

383 U. S. 745, 782-84 (1966):

A majority of the members of the Court expresses

the view today that §5 empowers Congress to enact

laws punishing all conspiracies to interfere with the

exercise of Fourteenth Amendment rights, whether or

not state officers or others acting under the color of

state law are implicated in the conspiracy. Although

the Fourteenth Amendment itself, according to estab

lished doctrine, ‘speaks to the state or to those acting

under the color of its authority,’ legislation protect

ing rights created by that amendment, such as the

right to equal utilization of state facilities, need not

be confined to punishing conspiracies in which state

officers participate. Rather, §5 authorizes Congress to

make laws that it concludes are reasonably necessary

to protect a right created by and arising under that

amendment; and Congress is thus fully empowered to

determine that punishment of private conspiracies

interfering with the exercise of such a right is neces

sary to its full protection.

In his foreword to the review of the Supreme Court’s

1965 Term, former Solicitor General Archibald Cox put

the matter in practical terms (Cox, Constitutional Adjudi

cation and the Promotion of Human Bights, 80 Harv. L.

Rev. 91, 112 (1966)) :

17

It makes little difference to the Negro child or his

parents whether white thugs overwhelm the janitor and

bar the child at the schoolhouse door or stand a block

down the street threatening violence to children on

the way to school. The case is the same when parents

are threatened with loss of their homes, credit or em

ployment if their child attends a desegregated school.

The practical objective of the constitutional guarantee

is that Negroes should receive equal opportunities for

the use of facilities that the State provides. The na

tional interest is equally in the provision and enjoy

ment of the state facilities. From this standpoint,

there is just as much reason for Congress to have

power to deal with conspiracies and other private ac

tivities aimed at defeating enjoyment of the constitu

tional right as there is for it to proscribe private

interference with the State’s performance of its duty.

And Jones v. Mayer, supra, which gave wide scope to

the Enabling Clause of the Thirteenth Amendment, cer

tainly ratifies the view of the Enabling Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment expressed in United States v. Guest,

supra. See also Katsenbach v. Morgan, 384 IT. S. 641,

648-51 (1966).

The principal holding of Congress of Racial Equality v.

Clemmons, supra, supports plaintiffs right to relief.

There, the Mayor and law enforcement officials of the City

of Baton Rouge, Louisiana brought suit against C. 0. R. E.

under §1985(3), on the theory that C. 0. R. E.’s protest

demonstrations required so much police involvement that

other citizens received diminished police protection and

therefore were denied equal protection of the laws. This

Court replied (323 F. 2d at 61): “The contention has the

18

earmarks of a bad pun.” This Court went on to hold (323 F.

2d at 61):

The absence of a purpose on the part of the defen

dants to deprive anyone of rights to equal protection

of the laws distinguishes this case from Brewer v.

Hoxie School District, 8 Cir., 1956, 238 F. 2d 91. In

Brewer v. Hoxie, an Arkansas school district, which

had desegregated, was forced to close its schools be

cause of the activities of the defendants, who had en

gaged in a campaign of violence and intimidation. The

school district, its directors, and superintendent ob

tained an injunction in the federal district court

against the White Citizens Council and other organiza

tions and individuals from continuing interference

with their desegregation efforts. On appeal, the Eighth

Circuit refused to order the action dismissed. In the

Arkansas case the defendants made no bones about

their purpose. Their avowed object was to close the

Hoxie School in order to deprive the Negro children

of their right, under the Equal Protection Clause, to

attend a desegregated school. Here, unlike Brewer v.

Hoxie, there is no allegation in the complaint and no

evidence to suggest that the defendants purposefully

deprived others of their right to equal protection of

the laws.

In Brewer v. Hoxie School District No. 46, 238 F. 2d 91

(8th Cir. 1956), the desegregating school board sued the

members of private segregationist vigilante groups such as

“White America, Inc.,” “Citizens’ Committee Representing

Segregation in the Hoxie Schools” and “White Citizens’

Council of Arkansas.” There was no claim made that these

19

groups operated with any official participation.13 Among

other things, the school board alleged and proved that the

defendants “attempted by fear and persuasion to deter the

children from attendance at schools of the district” (238

F. 2d at 94). The Court of Appeals approved an injunction

restraining the defendants “from in any manner deterring

the attendance at school of children within said school dis

trict” (238 F. 2d at 94). In holding that the action was

properly brought under §1985(3), the Court of Appeals

held that the school board could sue to protect the rights

of the children (238 F. 2d at 104):

Action taken by private individuals against a school

board to prevent it from according equal protection

of the laws to the school children would result in a

deprivation of the school children’s rights under the

Fourteenth Amendment. . . .

# * # * #

The school board having the duty to afford the chil

dren the equal protection of the law has the correlative

right, as has been pointed out, to protection in per

formance of its function. Its right is thus intimately

identified with the right of the children themselves.

A fortiori, a child can sue to protect his own rights.

This is made clear by the language of §1985(3) itself: The

right of action is broadly given to “the party so injured

or deprived,” not simply to the “constituted authorities of

any State or Territory.”

13 See also Kasper v. Brittain, 245 F. 2d 92 (6th Cir. 1957), cert,

denied, 355 U. S. 834 (1957) and Bullock v. United States, 265

F. 2d 683 (6th Cir. 1959), cert, denied, 360 U. S. 909, 932 (1959).

2 0

Finally, it should be observed that the past inutility of

the statute stands in sharp contrast to the continuing need

to protect the citizen’s right to equal protection of the laws

—and particularly his right to a desegregated education—

from private violence. Anyone who has read the report of

the United States Commission on Civil Rights, Southern

School Desegregation, 1966-67, pp. 74-108 (July, 1967), can

have no doubt that private violence and intimidation re

main important barriers to desegregated education today.

To sum u p : the statutory language and history—and

reason and authority—compel a holding which will restore

§1985(3) as an enforceable instrument of Congressional

policy. The day is late, but not too late to keep the promise

the Nation made a century ago.

II.

Plaintiff Stated a Claim for R elief Under 42 U. S. C.

§ 1 9 8 5 (2 ) .

Plaintiff alleged that the purpose of the claimed con

spiracy was “to injure plaintiff and other Negro students

in their persons and property for lawfully enforcing and

attempting to enforce their rights to the equal protection

of the laws” (A. 25-26).

Since plaintiff had lawfully attempted to enforce his

right to a desegregated education as specifically guaranteed

by a federal court order, plaintiff clearly appeared to state

a claim under the following provision of §1985(2):

[I] f two or more persons conspire for the purpose of

impeding, hindering, obstructing, or defeating, in any

manner, the due course of justice in any State or Terri

21

tory, with intent to deny to any citizen the equal pro

tection of the laws, or to injure him or his property

for lawfully enforcing, or attempting to enforce, the

right of any person, or class of persons, to the equal

protection of the laws. . . ,14

But the court below held that plaintiff could not state a

sufficient claim under the invoked portion of §1985(2), ab

sent an allegation of state action. Neither reason nor au

thority supports this holding.

On its face, the invoked portion of §1985(2) fits this

case like a glove. By its plain language, it appears specifi

cally drafted to reach conspirators who act to impede the

enforcement of a court order guaranteeing a citizen’s right

to the equal protection of the laws. Given the background

of the Ku Klux Act of 1871, as previously analyzed, it

makes little sense to suppose that Congress intended to

reach only official conspirators in enacting this provision

as part of §2 of that act.

Nor do the few decided cases discussing the scope of this

statutory provision support the holding below. None of

them dealt with a claimed right to equality.15

This Court should enforce the provision according to its

plain meaning. Jones v. Mayer, supra, 392 U. S. at 420-22.

14 The enforcement clause is contained in §1985(3), set out

note 4, supra.

15 In Van Meter v. Sanford, 152 F. 2d 961 (5th Cir. 1946), re

lief was denied on the ground that “there is nothing said in the

petition about the equal protection of the laws, and petitioner is a

white man, and not of the race specially intended to be protected

by the statute” (152 F. 2d at 962). See also Mitchell v. Greenough,

100 F. 2d 184 (9th Cir. 1938), cert, denied 306 U. S. 659 (1939)

(Held: No showing of a purpose to deprive the plaintiff of equal

protection of the laws).

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, a federal court cannot refuse

to hear proof of claims of such denials of federally pro

tected civil rights as depicted by this ugly incident. If

plaintiff proves his case, he should have his remedy at

law. That is little enough, considering that, this case is

merely exemplary of a much broader wrong. The broader

remedy lies in the judicial recognition that, in many areas

of this Circuit, the “freedom of choice” method of school

desegregation does not work. Until this Court strikes at

the system which produced plaintiff’s injury, he and others

like him will be limited to their remedy at law. But at least

they should have that. The judgment below should be re

versed and plaintiff’s complaint reinstated.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Reuben V. A nderson

538% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on January 1969, I served two

copies of the foregoing Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant upon

T. H. Freeland, III, Esq., attorney for defendants-appel-

lees, by United States airmail, postage prepaid at Box 269,

Oxford, Mississippi 38655.

Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellant

RECORD PRESS, INC. — 95 Morton Street — New York, N. Y. 10014 — (212) 243-5775

38