Gibbs v. Arras Brothers, Inc. Respondent's Brief in Support of Motion for Reargument

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1918

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gibbs v. Arras Brothers, Inc. Respondent's Brief in Support of Motion for Reargument, 1918. b24dfd40-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/013e20de-6fd7-4dd5-abb0-1c91b230344a/gibbs-v-arras-brothers-inc-respondents-brief-in-support-of-motion-for-reargument. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

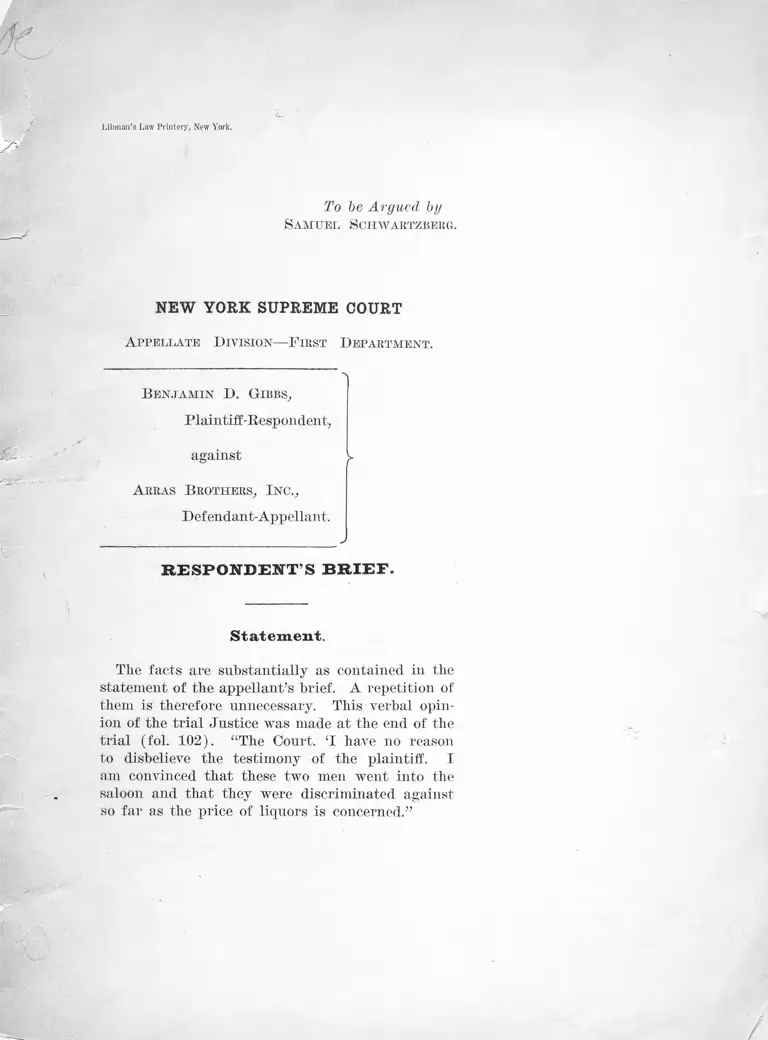

Libman’s Law Printery, New York.

To be Argued by

Samuel Schwabtzbeug.

NEW YORK SUPREME COURT

Appellate D ivision—F irst Department.

Benjam in D. Gibbs,

Plaintiff-Respondent,

against v

Arras Brothers, I nc.,

Defendant-Appellant.

________ __________ _________ _ ^

RESPONDENT’S B R IE F.

Statement.

The facts are substantially as contained in the

statem ent of the appellant’s brief. A repetition of

them is therefore unnecessary. This verbal opin

ion of the tr ia l Justice was made a t the end of the

tr ia l (fol. 102). “The Court. ‘I have no reason

to disbelieve the testimony of the plaintiff. I

am convinced th a t these two men went into the

saloon and th a t they were discriminated against

so far as the price of liquors is concerned.”

2

POINT I.

A saloon is a place of public accom

modation.

I t is a m atter of common knowledge and it

certainly was in the mind of the learned tria l

Justice, tha t all liquor saloons, in the City of

New York besides serving liquid refreshments,

m aintain free lunch counters for their customers

and also a lunch counter or tables or both, where

customers a t lunch time are served with meals,

with or w ithout drinks for which they pay, of

course. That such saloons also m aintain public

comfort stations, which as a m atter of fact the

“man on the street” may and frequently does

use for his convenience w ithout any charge, or

necessity for any consideration. I t Is also well

known tha t most saloons have news and stock

tickers, public telephones, Bullinger’s guides and

numerous other conveniences for the general pub

lic. In short, the saloons of this city as they are

conducted to-day, if not the most, are certainly

one of the most democratic of our institutions.

And it is well so, and for th a t reason they are

called “the poor man’s club”, for which the only

initiation or membership fee is the price of a

d rin k ; and so eager have saloon keepers been to

postpone the immediate payment thereof, tha t our

beneficent statutes have penalized such conduct

by barring suits by saloon keepers for the pay

ment of drinks had on their premises. To sum

it up, i t must be fairly conceded tha t in fact, a t

any rate, if not in law, saloons as a t present

conducted, are and are known to be places of

public accommodation in the fullest sense of the

word.

B ut notwithstanding this, the defendant urges

tha t the “poor man’s club” is not a place of

public accommodation. The sanctuary of the free

3

/

lunch and inspiration of the Raines Law Hotel,

assumes unto itself an exclusiveness, which would

bar from participating in its manifold benefits,

any one of whose race, creed or color its pro

prietor might not approve.

And to sustain this contention, the appellant

invokes two rules of statu tory construction,

namely, the rule of cjusdem generis and also the

rule of expressio unius est exclusio alterius, and

places complete reliance upon two analagous cases

in foreign jurisdictions, namely, Rhone v. Loomis,

74 Minn. 200; and K ellar v. Koerber, 61 Ohio St.

388;. and also in the case of Cecil v. Green, 161

111. 265. Such foreign decisions are, a t best, a

very slender reed to lean upon, because for almost

every decision of the courts of this .state, foreign

decisions can always be found diametrically on-

posed. And concerning the statute under dis

cussion and as a concrete example in point, in

the cases of People v. King, 110 K. Y. 418, and

Jones v. Broadway Roller Rink Co., 136 Wise.

595, the highest Courts of this state and of W is

consin respectively have held tha t a skating rink

is a place of public amusement, whereas the con

trary was held by the highest court of Iowa in

the case of Bowlin v. Lyon, et al. 67 Iowa 536,

and furtherm ore while the Courts of Ohio held in

K ellar v. Koerber (supra), th a t a saloon was not

a place of public accommodation, they on the

other hand in the case of Johnson v, Humphrey

Pop Corn Co. 24 Ohio Circuit Court, 135, held

th a t a bowling alley was a place of public accom

modation.

In fact after examining the appellant’s brief

upon this ; ppcai respondent's counsel was sorely

tempted to adopt i t as his own, and submit the

proposition solely upon the appellant’s brief.

W ere it not for the fact th a t this question now

appears before this Court for the first time, and

is of greater magnitude than the particular parties

4

involved in this action and affects millions of

the citizens of this State, of different races, creeds

and color, respondent would have so submitted.

But the im portance of the question involved com

pels a t least a passing review of the main cases

relied upon by the appellant.

Thus, at page 7 of appellant’s brief the follow

ing is quoted from the case of Rhone v. Loomis

( s u p ra ) :

“B ut here is a case where the legislature

has specifically enumerated in a somewhat

descending order according to rank or im

portance EVERY K1 NI> OF PLACE OF

REFRESH M EN T W H ICH WAS PR E SE N T

LY IN MIND TO W H ICH THEY IN TEN D

ED TH E ACT TO APPLY, but have omitted,

APPARENTLY PURPOSELY, to enumerate

places where intoxicating liquors are sold as

a beverage.”

Is such a condition present in our own statu te?

Obviously not. In this connection the statu te

sued upon only provides,

“All persons within the jurisdiction of this

State shall be entitled to the full and equal

accommodations, advantages, and privileges

of A N Y PLACE OF PUBLIC ACCOMMODA

TION, resort or amusement, subject only to

the conditions and limitations established by

law and applicable alike to all persons. * * *

“A place of public accommodation, resort

or amusement w ithin the meaning of this

article, shall he deemed to include any inn,

tavern, or hotel whether conducted for the

entertainm ent of transient guests or for the

accommodation of those seeking health,

recreation or rest, any restaurant, eating-

house, public conveyance, on land or water,

bath-house, barber shop, theatre, and music

hall.”

5

[Note th a t among these there is no place men

tioned where drinks alone are customarily served.

In the Minnesota statute, soda w ater fountains

and ice-cream soda parlors are mentioned. In

view of th a t fact the Minnesota Court’s ruling

has a certain amount of justification.

In referring to K ellar v. Koerber (supra) ap

pellant on page 9 of his brief says,

“For, reasoned the Court, the general policy

of the law is, and always has been, to dis

courage the sale of liquor—not to encourage

it—and a penalty will not be imposed for the

) sale of th a t which it has always been sought

to stop.”

A ppellant however does not go further, and

contend as he logically should tha t such is the

general policy of the law of this state. And far

be it from the appellant of all persons to claim

th a t i t is so, for once such a dictum finds lodg

ment in our decisions it will not profit the

calling of the appellant, but will in time rebound

against him as a boomerange.

The substance of the decision of the Illinois

Court in Cecil vs. Green (supra) is. contained in

the concluding paragraph thereof, which is quoted

as page 10 of appellant’s brief. That case holds

nothing more than th a t a drug store with or w ith

out a soda fountain is not a place of public ac

commodation. Reading this decision carefully

will disclose th a t it does not hold th a t a soda

w ater fountain conducted independently or an

ice-cream soda parlor is not a place of public

accommodation. W hat, therefore, does i t prove in

connection with a saloon? Surely, putting a soda

fountain in a drug store which deals in, and is

engaged in compounding, drugs and medical

preparations does not make such a. drug store any

more a place of public accommodation than the

selling or serving of bromo seltzer or zoolak by

. §

saloon keepers, makes the saloon a drug store.

W ould a saloon which serves such a drink be com

pelled to m aintain a registered drug clerk and

comply w ith the other provisions regarding a drug

store, simply for the reason th a t an occasional

customer orders such a drink, perhaps to over

come the effects of indulging “not too wisely but

too well” in other drinks obtained in the same

place?

And while examining the cases relied upon by

the appellant it may be well to point out their

inherent weakness, which is best done in the words

of the dissenting judges who sat upon them. In

Rhone v. Loomis (supra) a t page 206, Chief

Justice S ta rt of the S tate of Minnesota says:

“The statu te was intended to cover places

other than those specifically mentioned. E f

fect must be given to the general terms and

other places held to be w ithin the purview

of the statute. W hat other places of refresh

ment and accommodation? Clearly places of

the same general classes or kind as those spe

cifically enumerated, blow, a restaurant and

saloon are ejusdem generis when the words

are used in the ordinary meaning, as they

are in the statute. They are places to which

the public are invited for refreshments in

the form of food or drink, or both, as is often

the case with restaurants. Why saloons were

not specifically mentioned in the statute, I

do not know, unless i t was for the purpose of

euphemising the legislative in ten t as to them.

IS a t w hatever m ay have been the

reason, l am of the opinion th a t the

s ta tu te w ill not adm it of any reason

able construction which w ill exclude

saloons f rom its general item s,”

and Associate Justice Collins of the same Court

a t page 207 w rites :

7

“The purpose of the state, if it has any at

all, is to confer equal rights upon the colored

man in all public places. I t expressly pro

vides tha t colored persons shall have equal

accommodations, advantages, privileges and

facilities a t all inns, hotels, restaurants, and

'other places of public resort, refreshment,

accommodation or entertainm ent.’ In view of

this positive enactment, would i t be held that

an inn or a hotel, or a restaurant in which

liquors are kept for the express purpose of

serving a t tables when called for, could law

fully refuse to furnish those articles to a man,

properly seated a t a table, because of his

color? I TH IN K NOT; and if so, it seems

as if the saloon is to be regarded as a sort of

sanctuary, not to be profaned by the admis

sion and entertainm ent of the colored man.

* * * I am. decidedly of the opinion that- the

saloon is one of the 'other places of public

accommodation or entertainm ent’ mentioned

in the law. IF IT IS NOT, w h a t p la c e

is?

Furtherm ore in considering the decisions of

foreign jurisdictions, there is nothing before this

Court to show th a t saloons are conducted in the

same manner in Ohio and Minnesota as they are

here in New York. They surely have not the-

same Excise Laws th a t we have, and i t may be

tha t in these States saloons have not the same

accommodations above outlined present in saloons

in this state, showing the strong sim ilarity be

tween saloons and restaurants in New York City

particularly. Concerning the case of Rhone v.

Loomis (supra) and Keller v. Koerber (supra)

Lewis’ Sutherland's S tatutory Construction, page

842 says:

“The general words were held not to include

saloons, although THEY WOULD SEEM TO

BE EJU SD EM G EN ERIS.”

8

In the case of Babb v. El,singer, which was

argued before the Appellate Term in this D epart

ment, a t the January 1914 term, th a t Court

squarely decided in April, 1914 th a t a saloon was

a place of public accommodation within the Civil

Bights Law then in existence which was Chapter

14 of the Consolidated Laws. That deecision was

rendered by the unanimous Court affirming upon

the opinion in the Court below and while not

officially reported, i t appears in 147 K. Y. Supp.

98 and was also published in the INew York Law

Journal, on April 25th, 1914. In th a t case which

was tried in the Municipal Court before Mr.

Justice Spiegelberg and a Jury , the defendant

after a verdict brought in for the plaintiff, made

a motion to set the same aside on the usual

grounds and on the further ground th a t a saloon

was not a place of public accommodation within

the law. The learned tria l Justice reserved his

decision on the motion insofar as i t involved the

question concerning a saloon being a place of

public accommodation and thereafter handed down

his decision denying the motion and holding tha t

a saloon was such a place. In view of the fact

th a t this decision was adopted by the Appellate

Term in its unanimous affirmance, and it fully

considered and discussed the authorities now re

lied upon by the appellant i t would not be amiss

to quote from the same. A ppellant’s authorities

are commented upon as follows:

“I t is true in the only two cases which I

was able to find where a similar question,

as in this case, has arisen, i t was held tha t

the term ‘saloon’ was not included w ithin the

meaning of statutes containing similar pro

visions as in our Civil Rights Law. Kell a r

v. Koerber, 61 Ohio St. 388, Rhone v. Loomis,

74 Minn. 200. In the Ohio case, the reason

is squarely placed upon the theory th a t the

9

liquor traffic is an evil which, should be dis

couraged and restricted, and th a t the Civil

Rights act should not be construed as en

couraging a traffic which the clearly defined

policy of the State of Ohio discourages. In

the Minnesota case, the Court by a bare

m ajority seems to have adopted the same view.

* * * I am not aware th a t such a theory has

found lodgment in the policy of the State

of Yew York. The other reasons set forth

by the m ajority of the Court in Rhone v.

Loomis, supra, in my opinion are neither

persuasive nor logical, and are fully met in.

the two dissenting opinions. * * *

Y or is the case of Cecil v. Green 161 111.

265, applicable. In tha t case it was held tha t

a soda fountain kept in a drug store was not

a public place w ithin the meaning of the

statute, for the reason th a t 'tha t such places

can be considered places of accommodation

or amusement to no greater extent than a

place where dry goods or clothing boots or

shoes, hats and caps, or groceries are dis

pensed.’ * * * Sufficient perhaps too much

has been said to show that, i f any place, a

saloon is a place of public accommo

dation w ith in the scope of the civil

rights ac t.”

The Appellate Term of this Departm ent had

also by inference held in the case of Fuller v. Mc

Derm ott which is not officially reported but ap

pears in 87 Y. Y. Supp. 536, th a t a cause of action

against a saloon keeper would lie for a refusal

to serve a colored man with a glass of beer a t a

liquor saloon because of his race or color. This

was under the Laws of 1895 Chapter 1042, Page

974. Outside of these two decisions by Courts

of lower jurisdiction, the only other decisions

reported in this S tate passing upon the question

as to any places not specified being included

10

w ithin the purview of the statu te are those of

People v. King, 110 N. Y. 418 and Burks v. Bosso

180 N. Y. 341.

In the case of People v. King (supra), the Court

of Appeals sustained a conviction of the defendant

under the penal statu te for discrim inating against

a colored man in connection w ith a skating rink,

which it held was a place of public amusement.

In the case of Burks v. Bosso (supra), the

Court of Appeals reversing the Appellate Division

held th a t a bootblack stand in the hall of an

office building was not a place of public accommo

dation. In this case, the Court of Appeals con

tra ry to the in terpretation placed on its decision

by the appellant, signified its intention and desire

NOT TO LIM IT or confine the number or kind

of places to which the Law applies and 'NOT to

narrow itself by any application of the doctrine

of EJU SD EM G E N E SIS or any other principle

of construction, so th a t each case should be con

sidered solely upon its merits, as appears a t page

344 in the opinion of W erner, J :

“We do not deem it necessary a t this time

to enter into a discussion as to how far the

sovereign power may go in restricting the in

dividual rights and privileges which inhere

in some of the callings enumerated in the

statu te under consideration, because we are

of the opinion th a t the phrase ‘and all other

places of public accommodation’ does not

include bootblacking stands.”

There is surely a vast difference between a boot-

black stand in a hall of an office building and a

saloon; an office building, w ith or w ithout a boot-

black stand is strictly a private place, although

throngs may enter and leave i t in the course of a

day; whilst a saloon, even in the most isolated

place and w ith a minimum of patrons is never the-

11

less a public place and of c-onrse a place of public

accommodation.

Quoting again from decision, in the case of Babb

v. Elsinger (supra) :

“In discussing the statu te (St. 5 and 0

Edw ard VI, ch. 25), dealing with visitorial

powers over ale houses,, i t is said in a note

in Stephens v. Watson, Salk 45: ‘This statu te

extends not to inns, for they are for lodging

of travelers; but if an inn degenerate to an

alehouse by suffering disorderly tippling, etc.,

i t shall be deemed as such.’ And in Over

seers of the Poor v. W arner, supra, 3 Hill,

a t page 157, i t is said: ‘A t common law, any

i person may erect an inn for the public accom

modation, without a license ; as the lSeeeping

of i t is not a franchise, bu t a lawful trade,

open to- every citizen.’ I f an inn is a place

of public accommodation, why not a place

where intoxicating liquors are sold in which

the public has, from the earliest times, shown

greater solicitude than in inns? I t is of the

greatest significance tha t in England the

equivalent of the word ‘saloon’ as used in this

country is the word ‘public house.’ The Ox

ford English Dictionary gives the following

definition of public house: ‘A house for the

1 entertainm ent of any member of the com

munity, in consideration of payment. (a)

An inn or hostelry providing acommodation

(food and lodging,, or light refreshments) for

travelers or members of the general public,

usually licensed for the supply of ale, wines

and spirits. isTo<w commonly merged in ‘b’.

(b) in current restricted application: A

. house of which the principal business is- the

sale of alcoholic liquors to be consumed on

the premises; a tavern.’

I t may not be amiss to add th a t while in

12

this country the term ‘tavern’ is a synonym

of inn and hotel (People v. Jones, supra),

in England it signified ‘a house in which per

sons are regaled with wines and other liquors,

but not with the more substantial entertain

ment of the victualing house.’ ( Will cock

Laws of Inns, p. 1. 1; see also, Oxford English

Diet., sub. Tavern). ,

I t is well known th a t hotels and restau

ran ts usually contain saloons or drinking

bars. If, therefore, the contention of the

learned counsel for the defendant is correct,

we would be confronted w ith the anomalous

situation th a t a proprietor of a saloon may

discriminate against a colored citizen, so long

as it is detached from a restauran t or a

hotel, bu t comes w ithin the prohibition of the

statu te if the saloon is located in a restau

ran t or hotel.”

I t is thus shown th a t the resemblance between

a saloon and a restaurant, inn, tavern or hotel

is now and since the time of King Edw ard VI,

has been recognized as being more than super

ficial as contended by appellant.

In the light of all the decisions set forth find of

the reasoning of the authorities, is it too much

to claim tha t a liquor saloon as conducted in this

City is as much, if not more a place of public

accommodation, as a skating rink is a place of

public amusement. (See People v. King, supra.)

POINT II.

Section 40 of Chapter 265 of the Taws

of 1913, include saloons.

A ppellant contends (appellant’s brief p. 17)

tha t because of the change in the statute caused

1 o

it)

by the amendment to the previous Civil Rights

Law,

“tha t the statem ent of the specified places,

following as i t does, the general statement

brings this statute within the well settled

rule th a t the mentioning of some, excludes

all others.”

In view of the decision of the Court of Appeals

in the case of People v. King (supra) which holds

tha t a skating rink (which is not specified in the

statu te) is nevertheless included w ithin i t

as a place of public amusement, in order to arrive

a t the conclusion which the appellant does, it

m ust be necessary to assume th a t the legislature

in passing the present statu te repealed the former

one under which th a t decision was rendered. Any

other conclusion would be inconsistent w ith ap

pellant’s contention.

In the recent case of People v. Dwyer, et al.

which is reported in the New York Law Journal

of May 20th, 1915, the Court of Appeals laid down

the following rule regarding repeal by implication.

“The general rule is tha t a statu te £is not

repealed by implication, unless the two

statutes are manifestly repugnant, and in

consistent, or the la ter statu te covers the

whole subject m atter and was intended as a

substitute for the former. * * * A repeal of

a statu te by implication is not favored, and

is only allowed when the inconsistency and

repugnancy of the two acts are plain and

unavoidable. * * * The intent of the Legisla

tu re must prevail, and a statu te will not be

deemed to have been repealed by a la ter

statute, if the two are not clearly repugnant,

unless the in ten t to repeal is clearly ind i

cated.’ (Citing Mongeon v. People, 55 N.

Y., 613, 615; Smith v. People, 47 N. Y., 330;

see Bowen v. Lease, 5 H ill, 221; Davis v.

Supreme Lodge, K. of H., 165 N. Y., 159;

14

P ra tt Institu te v. City of New York, 183

N. Y., 151; People v. H arris, 123 N. Y. TO.)

On this point also Lewis’ Sutherland, on S ta tu

tory Construction on page 458 (Section 24(5)

s ta te s :

“A repeal will take effect from any sub

sequent statu te in which the legislature gives

a clear expression of its will for th a t pu r

pose.”

and again a t page 4(51 (Section 247) says further,

“Such repeals are recognized as intended

by the legislature and its intention to repeal

is ascertained as the legislative in ten t is as

certained in other respects, when not ex

pressly declared, by construction. An im

plied repeal results from some enactments,

the terms and necessary operation of which

cannot be harmonized with the term s and

necessary effect of an earlier act.

(P. 464) The intention to repeal however,

will not be presumed, nor the effect of repeal

admitted, unless the inconsistency is un

avoidable, and only to the extent of the re

pugnance.”

In comparing the two- statutes, can anything

be found in the present statu te whereby the terms

and necessary operation thereof cannot be har

monized with the terms and necessary effect of the

former act as construed in Babb v. Elsinger, supra.

There is surely no repugnance between the pro

visions of the former statutes and the present

one, the only effect of the amendment being: to

specifically include within- the scope of the statute,

certain places concerning which there may have

been a question under the former statutes and for

bidding the doing, of certain things in addition

to those prohibited in the former Civil Rights

Law.

The prim ary rule of statu tory construction as

15

laid down by Lord Bacon (IV Lord Bacon’s

Works, 1.87) is thus expounded:

“I would wish”, says Lord Bacon, “all

readers tha t expound statutes to do as scho

lars are willed- to do; th a t is, first to seek

out the principal verb; th a t is to note and

single the m aterial words whereupon the

statu te is framed; for there are in every s ta t

ute certain words; which are as veins where

the life and blood of the Statute cometh and

where all doubts do arise.”

Applying this test to the statu te in question,

the present Civil Rights Law, i t becomes manifest

th a t the principal verb contained in Section 40

is “shall be deemed to include.”

“The word ‘include’ has two meanings,

the first which accords with its etymology,

from ‘eland,ere’ ‘to shut, is to confine w ith in ;

to shut up ; to hold,—as, the shell of a nu t

includes the kernel; a pearl is included in

a shell.’ W ebster’s Dictionary. The second

and derivative meaning is ‘to comprehend;

as, a genus the species, the whole, a p a rt’.”

Hibberd v. Slack 84 Fed. 571, 576, 577.

“The word ' include’ has two shades of

m eaning.. I t may apply where th a t which

is affected is the only thing included * * *

I t is also used to express the idea tha t the

thing in question constitutes a p a rt only .

of the contents of some other thing.’ THE

LATTER SENSE W E CONSIDER the

most usual.” Dumas v. Boutin, McGloin

(La.) 274, 277, 278.

According to the context the term is often used

as. a word of extension and not of limitation.

See in this connection Reg. v. Kershaw, 6 E. &

B. 999. 1007; 2 Ju r. N. S. 1139: 26 L. J. M. C.

19; 5 Wldy. Rep. 53; 88 E. C. L. 999.

The words “shall include” (in statute) are

16

not identical with or put for “shall mean;’

Reg. v. Hermann, 4 Q. B. D. 284, 288; 14 Cox.

C. C. 279; 48 L. J . M. C. 106; 40 L. T. Rep.

2ST. S. 268, 27 Wklv. Rep. 475.

Including” is not a word of limitation.

Rather is it a word of enlargement, and in ordi

nary signification implies th a t something else has

been given beyond the general language which

precedes it. N E IT H E R 18 IT A WORD OF

EN U M E R A TIO N as by the express terms of the

language of gift. In a bequest “of all my personal

property” including furniture, plates, etc., the

word “including” was not held to limit the

bequest to the property enumerated after the

wording, but to cover all of the testa to r’s prop

erty. In Re Goetz, 71 App. Hiv. 272.

“Including” as used in Comp. St. p. 578,

Sec. 9, providing th a t the clerk m ust insert in

the entry of judgment the necessary disburse

ments “including the fees of officers allowed

by law, the fees of witnesses, of commissions,

the compensation of referees, and the expenses

of prin ting papers on appeal”, does not neces

sarily confine the items of disbursements re

coverable to those enumerated.

Cooper v. Stinson, 5 Minn. 522.

I t cannot therefore be seriously urged th a t

judicial construction limits application of a s ta t

ute in which the word “include” is used only

to those places enumerated because of the appear

ance of th a t word. N either does the application

of the doctrine expressio unius eat exclmio

alterius so lim it a statute.

Lewis’ Sutherland on S tatutory Construction

a t page 916 states as follows:

“E X PR ESIO UNIUS EST EXCLUSIO

ALTERIUS. This maxim, like all rules of

construction is applicable under certain con

ditions to determine the intention of the law

maker, when it is not otherwise manifest.

Under these conditions it leads to safe and

17

satisfactory conclusion. BUT OTHERW ISE

the expression of one or more things is not

a negation or exclusion of other things.”

And again, a t page. 924, the same author fu r

th e r s ta te s :

“The maxim does not apply to a statu te

the language of which may fairly compre

hend many different cases, in which some

only are expressly mentioned by way of

example merely, and not as excluding others

of a. similar nature. The mention of one

thing is not exclusive when the context shows

a different intention.

See also the case of Grubbe v. Grubhe, 26

Oreg. 363, in which the Court holds tha t

the principle is not of universal application,

and tha t great caution should be exercised in

its use.”

As stated by th e same author, Volume 2 a t

page 693 (Sec. 363):

“The in tent is the vital part, the essence of

the law and the primary rule of construction

is to ascertain and give effect to th a t in

ten t.” (See the numerous authorites quoted

there.)

And the Court of Appeals in the case of

M anhattan Co. v. Kaldenberg, 165 1ST. Y., a t page

7, reiterates and amplifies this principle of con

struction in the following w ords:

“In constructing statutes the proper course

is to s ta rt out and follow the true in tent

of the Legislature and to adopt th a t sense

which harmonizes best with the context and

promotes in the fullest manner the apparent

; policy and object of the legislature.’

I t therefore becomes absolutely necessary to

examine into the policy and the in ten t of the

legislature in enacting the Civil Rights Statutes

18

in spite of the statem ent of the appellant (page

18) “th a t with the intention of the legislature we

cannot conjure.”

The Court of Appeals has announced in the

rase of People v. King, 110 N. Y. 418, at page

424, the following as the intent of the legislature

in passing this law.

“IT CANNOT BE DOUBTED THAT IT

WAS ENACTED W ITH SPECIAL R E F E R

ENCE TO CITIZENS OF AFRICAN DE-

SC'ENT, NOR IS TH ERE ANY DOUBT

THAT THE POLICY W H ICH DICTATED

THE LEGISLATION WAS TO SECURE

TO SUCH PERSONS EQUAL RIGHTS

W ITH W H IT E PERSONS TO TH E FA CIL

IT IE S FU R N ISH ED BY CARRIERS, IN N

K EEPER S, THEATRES, SCHOOLS AND

PLACES OF PUBLIC AMUSEMENT.”

Similarly in the case of Joyner v. Moore W ig

gins Co., 152 App. Div., 260, (recently unanimous

ly affirmed by the Court of Appeals, 211 N. Y.,

522), a t page 268, holds,

“TH E IN TEN T AND OBJECT OF THE

STATUTE WAS TO SECURE TO ALL

PERSONS, REGARDLESS OF RACE,

CREED OR COLOR, FULL AND EQUAL

ENJOYM ENT OF TH E PR IV ILEG ES AND

FA C IL IT IE S TH ER EIN SET FORTH.”

In going into the causes and history of the s ta t

ute the Court of Appeals, in the case of People v.

King, supra, says:

“The race prejudice against persons of

color, whch had its root, in p a rt at least, in

the system of slavery, was by no means ex

tinguished when, by law, the slaves became

citizens and freemen. They became entitled

to all the privileges of citizenship, although

the great mass of them were poorly prepared

to discharge its obligations. The nation se

19

cured the inviolability of the freedom of the

colored race and their rights as citizens by

the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and F ifteenth

Amendments of the Constitution of the United

States.”

And lastly in the case of Burks v. Bosso, 81

App. Div., 530, Mr. Justice Spring, w riting the

prevailing opinion, states the policy and construc

tion of the statu te as follows:

“I am mindful th a t a statu te both criminal

and penal in its im port is ordinarily to be

construed strictly. TH E LEGISLA TIV E

INTENT, HOW EVER, MUST CONTROL.

W here th a t in ten t has been unvaryingly mani

fested in one direction and th a t in prohibition

of discrimination against a large class of

citizens, the Courts should not hesitate to

keep pace w ith the legislative purpose. We

must remember th a t the slightest trace of

African, places a man under the ban belong

ing to th a t race. However respectable and

worthy he may be, he is ostracized socially,

and when the policy of the law is AGAINST

extending the prohibition to his civil rights,

a liberal ra ther than a narrow interpretation

should be given to enactments evidencing the

IN TEN T to eliminate race discrimination, as

far as th a t can be accomplished by legisla

tive intervention.”

I t is needless and unprofitable to go any further

into this point, but i t cannot be closed without

reference to the learned opinion of Mr. Justice

H arlan, of the United States Supreme Court, in

the case of Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S., 3, and

more especially a t page 48, and also the strong

dissenting opinion of Justice Collins, in Rhone v.

Loomis, supra, above quoted. (See also Joyner v.

Wiggins, 152'App. Div., 266, p. 268).

Another significant fact which the Court should

consider in this connection is th a t the policy of

20

the legislature, as evidenced by the statu te sued

upon, is to broaden rather than lim it the scope

of the former statutes, by making it a crime to ad

vertise the doing of anything prohibited in the

statute, and specifically extending the scope there

of to summer hotels and health resorts, as well

as making a cause of action thereunder assign

able. Surely this does not indicate on the part

of the Legislature any in ten t to lim it the scope

of the statu te in question within the narrow con

fines of the places specifically enumerated in it.

If the legislature had intended to reverse the ef

fect of the decision of the Court of Appeals in

People v. King, i t would surely have indicated its

intention to do so in a more pronounced and cer

ta in manner than by broadening the scope of the

statu te in the manner stated.

In conclusion, a word of reply to the veiled

strictures against the race of plaintiff, contained

a t page 22 of appellant’s brief, would not be out

of place. True it is, and it would be miraculous

were i t otherwise, th a t there are disorderly and

criminal colored men as there are whites. W hat

the poportion is, as far as this State is concerned,

we are in no position to state. However, a race

which w ithin two generations after its freedom

from slavery, has accomplished the achievements

and reached the heights attained by many of its

members in every branch of the arts, science, le t

ters and industries, does not require in its behalf

our feeble efforts as apologist or defender. And

fa r be i t from us to place in the shadow the ef

fect, upon the colored race, of such a narrow'

minded and bigotted construction of this statute

as is sought by the appellant, and to put into a

stronger light the effect thereof upon the mem

bers of other different races, creeds or colors. But

although appellant’s counsel “conjectures” tha t

one reason wrhy saloons are not specified in the

act is tha t the legislature had in mind th a t “if

colored and white people are perm itted to mix

and be served a t the same bar i t may not always

21

mean th a t they will fraternize,” the fact still re

mains tha t such an argument can be advanced

against enforcing the present statute in reference

to every place specified in i t and discrimination

in public places teas forbidden by the common

law (Faulkner v. Solazzi, 79 Conn., 541).

W hat right has appellant to assume th a t the

legislature would not believe the police force of

this city competent to meet any case of ordinary

disorder occurrng in a saloon used by colored men

or by white men. And in this great State of New

York and in the City of New York, which con

tains most of the colored people of the State, what

proportion of them go into saloons, much less sa

loons frequented by whites. I t is well known and

may not be wrong to call the Court’s attention to

the fact, th a t saloon keepers in localities where

colored patrons are not desired, under the present

statute, (which most of them believe covers sa

loons), are making i t extremely disagreeable for

any such colored patrons.

F inally in view of the decisions of the Courts of

this State, declaring its policy in reference to dis

crimination against the colored race as far as

their civil rights are concerned, how can any logi

cal argum ent be advanced in aid of the contention

th a t only such places as are specified within the

law are covered by it.

POINT III.

The appeal from the judgment should

be dismissed and the judgment in favor

of the plaintiff affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

SAMUEL SCHWARTZBERG,

A ttorney for Plaintiff-Respondent.

[933]

P r e ss of F r e m o n t P a y n e , 47 B ro a d S t.— ’P h o n e s , 2277-78-79 B ro ad .

To be Argued by

I. Maurice W ormser.

(Emtrt of Appeals

State of New York.

Benjamin D. Gibbs,

Plaintiff-Respondent,

against

Arras Brothers, I nc.,

Defendant-Appellant.

RESPONDENT’S BRIEF IN SUPPORT

OF MOTION FOR REARGUMENT.

This brief is respectfully submitted on bebalf

of plaintiff-respondent on his motion submitted

herewith for a reargument of the appeal herein.

The case was decided by this Court on January

15, 1918, the opinion of the m ajority being w ritten

by Judge Collin. Three judges dissented, with

out opinion.

The case is one of great public importance and,

unfortunately, was submitted to this Court by the

appellant w ithout oral argument. We respectfully

submit th a t the following points were inadvert-

2

(‘lit ly overlooked by this Court, and that, therefore,

a reargument should be g ran ted :

(1) That this Court inadvertently overlooked

the fact tha t a saloon is a place of public resort

even if not a place of public accommodation. The

S tatu te (Civ. Eights L., Sec. 40), declares th a t all

persons shall be entitled to the full and equal ac

commodations of any place of public resort, and,

with the utmost deference to this Court, we suggest

th a t a saloon surely must be regarded as a place of

public resort, even if not, perhaps, technically, a

place of public accommodation,

(2) That this Court inadvertently overlooked

the fact th a t the case of Burks vs. Bosso, 180 1ST. Y.,

341, upon which it relies in its opinion, was de

cided under the Laws of 1895, ch. 1042, before the

amendment of 1913, L, 1913, ch. 265, now consti

tu ting Civil Rights Law, Sec. 40-41, and that, in

point of fact, the amendment of 1913 was enacted

in order to give greater efficacy to the policy of the

original statutes.

(3) That this Court inadvertently overlooked

the fact th a t the Law of 1895, under which the

decision in Burks vs. Bosso, 180 hi. Y., 341, was

made, did not extend to places of “public resort,”

but only mentioned “places of public accommoda

tion or amusement.” Whereas the amendment of

1913 under which the present suit was brought, ap

plies to places of public resort as well as to places

of public accommodation or amusement, and the

present statute, while it states tha t certain places

shall be deemed to be included, does not exclude

other places provided they come within the general

term “public resort.”

(4) That this Court inadvertently overlooked

the interpretation placed upon statutes of this kind

by this Court itself in the leading case of People

Vs. King, 110 N. Y>, 418, particularly a t pages 425-

427, in which case the opinion was w ritten by

Judge Charles Andrews, a recognized authority

Upon, questions of public policy and the police

power.

(5) That this Court inadvertently overlooked

the fact tha t the word ‘Tavern” has been judicially

defined to be a house to which a license to sell

liquors in small quantities to be drunk on the spot

has been granted, and th a t it has been held tha t

the term “tavern” is practically synonymous with

“barroom” or “drinking shop.”

3

POINT 1.

This Court inadvertently over

looked the fact that a saloon is a

place of public resort, even if not a

place of public accommodation. The

Statute (Civ. Rights !>., Sec. 40), de

clares that all persons shall be en

titled to the full and equal accommo

dations of any place of public resort,

and, with the utmost deference to

this Court, we Suggest that a saloon

surely must be regarded as a place

of public RESORT, even if not, per

haps, technically a place of public

accommodation.

A saloon, we respectfully submit, is a place of

public resort, even if not a place of public accom

modation. The present statu te (Civ. Eights L.,

4

Sec. 40) declares tha t places of public resort, as

well as places of public accommodation or amuse

ment, are included. A saloon, even if not a place

of public accommodation, is a place of public re

sort. Judicial notice should be taken of this cir

cumstance. In fact, in England, a saloon is known

as a public house. In this country, many of us be

lieve tha t saloons are not desirable, but whether

we think so or do not think so, it is respectfully

submitted th a t a saloon is surely a place of public

resort. In point of fact, the circumstance th a t a

saloon is a place of public resort is one of the very

reasons why many of us object to saloons and re

gard them with disfavor.

In the opinion, w ritten on behalf of this Court,

by Judge Collin, no mention is made of saloons as

places of public resort, and it would seem th a t the

m ajority of this Court inadvertently overlooked the

changed terminology of the present statute.

A t the outset of the m ajority opinion, this Court

states tha t the question herein is: “Is a liquor

saloon a\ place of public accommodation, w ithin the

intendment of the statute.” W ith all deference, we

respectfully submit th a t this is not a t all the ques

tion involved. The question is rather, “Is a liquor

saloon a place of public resort or public accommo

dation w ithin the intendment of the statute.”

I t seems to the w riter tha t careful consideration

should be given by this Court to the proposition

whether a saloon may not reasonably and fairly be

deemed to be a place of public resort, even if not a

place of public accommodation.

I t has been held th a t where intoxicating liquors

are kept in a house and sales are made therein, it

may properly be regarded as “a place of public

resort.”

i n

state vs. Madison, 23 S. Dak., 584, 122 1ST.

W., 647, 650.

And surely, on reason and on sound principle, a

saloon should be regarded as “a place of public re

sort.” If it is not, then w hat is?

POINT II.

The majority of this Court in its

©pinion, relies upon the case of Burks

vs, Boss©, 180 N. IT., 841, which was

decided under the Statute of 1895

(1. 1895, eh. 1042). The Statute of

1895, quoted by this Court in its opin

ion, applied to “places of public ac

commodation or amusement.” It did

not extend to “places of public

resort.”

The present statute (L. 1913, Oh, 265, now Sec.

40 of Civ. Rights Law), extends to places of public

resort as well as to places of public accommoda

tion or amusement. The present statu te reads, in

part, as follows:

"All persons w ithin the jurisdiction of this

state shall be entitled to the full and equal

accommodations, advantages and privileges

of any place of public accommodation, resort

or amusement, subject only to the conditions

and limitations established by law and appli

cable alike to all persons.”

We call careful attention to this insertion in the

present statute, whereas the earlier statute merely

read as follows:

6

“All persons within the jurisdiction of this

State shall be entitled to the full and equal

accommodations, advantages, and privileges of

inns, restaurants, hotels, eating-houses, bath

houses, barber shops, theatres, music halls,

public conveyances on land and water, and

all places of public accommodation or amuse

ment, subject only to the conditions and lim ita

tions established by law and applicable alike

to all citizens.”

The addition in the present statute is of obvious

significance.

POINT III.

This Court inadvertently over

looked. the fact that the Law of 1895,

under which the decision in Burks

vs. Boss©, 189 N. Y., 841, was made,

did not extend to places of “public

resort” but only mentioned, “places

of public accommodation or amuse

ment. Whereas the amendment of

1918 under which the present suit

was brought, applies to places of

public resort as well as to places of

public accommodation or amuse

ment, and the present Statute, while

it states that certain places shall be

deemed to be included, does not ex

clude other places provided they

come within the general term “pub

lic resort.”

The Burks vs. Bosso case was decided before the

amendment in 1913, which was made to include

places of public resort, and in point of fact, the

7

amendment of 1913 was framed by able counsel

and was enacted by the legislature in order to meet

the lim itations of the 1895 statu te and in order to

give greater efficacy to the original statu te in this

state (see Woolecott vs. Shubert, 217 N. Y., 219).

I t follows th a t the Bosso case, as an authority,

is of little, if any, weight in the decision of the in

stan t case. I t interprets an entirely different s ta t

ute—in fact, a statute which was insufficient and

Which was la ter amended in order to meet the

insufficiencies and inadequacies in i t which this

Court pointed out in the case of Burks vs. Bosso

(supra) . I f the statute, as it now stands, is in

adequate and insufficient, it is hard to conceive

how an adequate statu te could be framed, because

the in ten t of the present sta tu te was absolutely

to include all places of public resort as well

as of public accommodation and amusement.

While the present statute, i t is true, states th a t cer

ta in places shall be deemed to be included, it does

not exclude other places provided they come w ith

in the purview of the general term, “public resort.”

POINT IV.

Tills Court inadvertently over

looked the interpretation placed

upon Statutes of this kind by this

Court itself in the leading- case of

People vs. King, 110 N. Y., 418, partic

ularly at pages 425-427, in which case

the opinion was written by Judge

Charles Andrews, a recognized - au

thority upon questions of public pol

icy and the police power.

In the leading case of People vs. King (supra),

this Court took occasion to say through Judge An

drews :

8

' “The race prejudice against persons of color,

which had its root, in part at least, in the sys

tem of slavery, was by no means extinguished

when, by law, the slaves became free men and

citizens

Tlie Court thus took notice tha t the purpose of

these statutes was to protect citizens of African

descent and to- confer upon them civil rights from

which they should not be excluded by reason of

their race or color.. I t is elementary th a t in the in-*

terpretation of a statute, a Court should bear in

mind the mischiefs and evils which the statute was

enacted in order to- suppress, and should consider

the statu te with reference, to the objects it had in

view.

In People ex rel. Wood vs. Ltteombe, 99 N. Y.,

43, 49, this Court sa id :

“In tlie interpretation o f statutes, the great

principle which is to control is the intention

of the legislature in passing the same, which

intention is to be ascertained from the cause

or necessity of making the statute, as well as

other circumstances.*’

In Republic of Honduras vs. Soto, 112 N. Y., 310,

313, -this Court sa id :

“The statute m ust be construed with refer-

ence to the object i t had in view, the evils in

tended to be remedied and the benefits expect

ed' to be derived from it.”

Chancellor K ent said in his Commentaries (page

495) :

“I t is the duty of judges to make such a con

struction as should suppress the mischief and

advance the remedy.”

9

Tn the leading case of People vs. King, 110 N. Y.,

418, this Court pointed out tha t the purpose of these

statutes under present discussion is to free colored

people from any brand of inferiority. Judge An

drews said (pages 426-627) :

“The members of the African race, born or

naturalized in this country, are citizens of the

state where they reside and of the United

States. Uotii justice and the public interest

concur in a policy which shall elevate them as

individuals and relieve them from oppressive

or degrading discrimination, and wTkich shall

encourage and cultivate a spirit which will

make them self-respecting, contented and loyal

citizens, and give them a fair chance in tne

struggle of life, weighted, as they are a t best,

with so many disadvantages, i t is evident

that to exclude colored people from places of

public resort on account of their race is to fix

upon them a brand of inferiority, and tends to

fix their position as a servile and dependent

people. I t is, of course, impossible to enforce

social equality by law. B ut the law in question

simply insures to colored citizens the right to

admission, on equal terms with others, to public

resorts and to equal enjoyment of privileges of

a quasi public character.”

This language is surely equally applicable in the

instan t case. I f a saloon is not a place of public

resort, what is f

We further beg to refer most respectfully to the

failure of the opinion of this Court to consider the

leading case of People vs. King (supra), and the

rules of construction of statutes of this kind laid

down by the Court in th a t case. While this Court

refers to Burks vs. Bosso, 180 N. Y., 341, it makes

no mention of Judge Andrews' epoch-making deci

30

sion in the case of People vs. King.. If a skating

rink may fairly be deemed a place of public amuse

ment, surely a saloon may fairly be deemed a place

of public resort, if not of public accommodation.

P O IN T V ,

Tliis Court inadvertently over-*

looked the fact that the word “tav

ern” lias bees judicially defined to he

a house to which a license to sell li

quors in small quantities to toe drunk:

on the spot lias been granted, and

that it has been held that the term

'“tavern” is practically sym & iiyiK Lons

with “barroom” or “drinking Shop.’”

The m ajority of this Court, in its opinion, as

sumes “th a t the legislature did not specifically de

clare a liquor saloon included.” I t is true th a t the

sta tu te does not specifically use the word “saloon.”

It, however, does mention the term “tavern.”

. The word “tavern” has been judicially defined to

be a house to which a license to sell liquors in small

iquantities to be drunk on the spot has been granted.

.The term “tavern” is practically synonymous with

.“barroom” or “drinking shop.”

In re Schneider, 11 Ore., 288, 297; 8 I'ac.,

289, 290.

State vs. Chamhli/ss, Chews (S. Car.)

220; 34 Am. Dee., 593.

. And, of course, “saloon” is synonymous with

“barroom” or “drinking shop.”

, In the case of In re Schneider (supra) , W atson,

C. J., said (page 297) :

“There can be no essential difference be

tween the original meaning: of the word

11

“tavern” and the word “barroom” or “drinking

shop.”

I t is true tha t the term “tavern” is not in com

mon use. But the w riter’s judgment would be tha t

a tavern as distinguished from an inn or hotel is a

place which sells liquors in small quantities pu r

suant to license.

This point deserves consideration, because the

term “saloon” does not appear to be used in s ta t

utes of this kind in this State. The greater in

cludes the less, and if colored people are entitled

to purchase liquors in inns, why should they not be

entitled a fortiori to purchase liquors in taverns

and saloons without discrimination?

FINAL POINT.

For all of the reasons above out

lined, it is respectfully submitted

that this Court should grant a rear*

gument of the appeal herein, espe

cially because the original appeal

was submitted without argument.

The question involved is one of great

public importance and the case has

aroused much discussion, and the

points inadvertently overlooked by

the opinion of this Court, seem to de

mand consideration. The writer

yields to no man in respect for this

Court, but the proposition of law in

volved in this case demands further

consideration.

Respectfully submitted,

SAMUEL SCHWARTZBERG,

Attorney for Plaintiff-Respondent.

I. Maurice W ormser,

of Counsel on present motion.

■ . r . i c C /;.• Vih.

ill