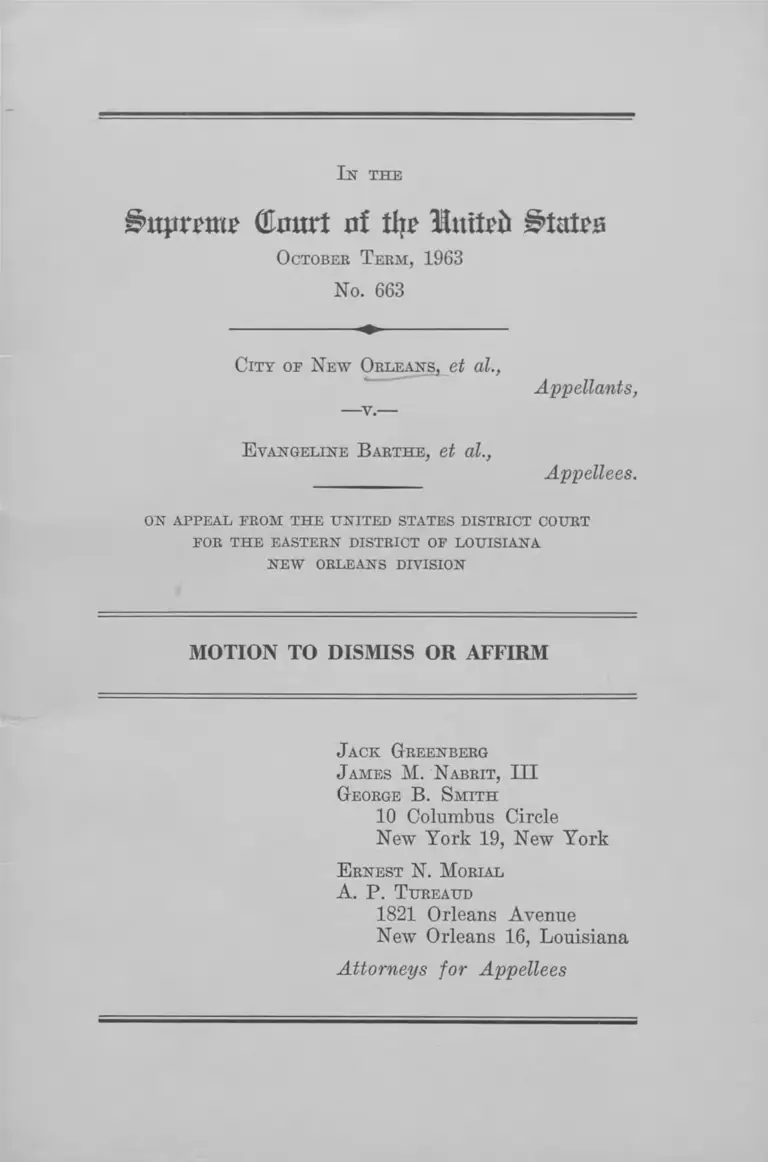

City of New Orleans v. Barthe Motion to Dismiss or Affirm

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of New Orleans v. Barthe Motion to Dismiss or Affirm, 1963. 8b44d364-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/01c5e3ca-4414-4706-82a7-0076739f066e/city-of-new-orleans-v-barthe-motion-to-dismiss-or-affirm. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

I n THE

G Im trt o f % Mnxttb S t a t e s

O cto ber T e r m , 1963

No. 663

C i t y o f N e w O r l e a n s , et al.,

—v.—

Appellants,

E v a n g e l in e B a r t h e , et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

MOTION TO DISMISS OR AFFIRM

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

J a m e s M . N a b r it , I I I

G eorge B . S m i t h

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

E r n e s t N. M o r ia l

A. P. T u r e a u d

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellees

I N D E X

Motion to Dismiss or Affirm.............................................. 1

Opinion B elow ....................................................... 1

Statute ................................................................................. 1

Questions Presented........................................................... 2

Statement ............................................................................. 2

A r g u m e n t :

PAGE

I. This Court Lacks Jurisdiction of This Appeal

Because No Three-Judge Court Was Neces

sary for Disposition Below. However, It

Should Take Certiorari Jurisdiction and Ren

der Judgment on the Merits ............................ 5

II. The Questions Presented by Appellants Are

Unsubstantial ...................................................... 7

C o n c l u s io n ..................................................... 12

T a b l e op C ases

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 3 1 .................................... 6

Barthe v. City of New Orleans, 219 F. Supp. 788 ...........6,11

Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University v.

Wilson, 340 U. S. 909 ...................................................... 10

Bohler v. Lane, 204 F. Supp. 168 (S. D. Fla. 1962) ....... 8, 9

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ................... 6

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 ............... 10

Brown v. South Carolina State Forestry Commission

(No. 774, E. D. S. C. July 10, 1963) .......................... 8

11

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 .................................... 6

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 .................................................................................... 6, 8

City of Greenboro v. Simkins, 149 F. Supp. 562 (M. D.

N. C. 1957), aff’d 246 F. 2d 425 (4th Cir. 1957) ......... 8

City of St. Petersburg v. Alsup, 238 F. 2d 830 (5th Cir.

1956) ................................................................................. 8

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsborough, 228

F. 2d 853 (6th Cir. 1956) ............................................. 10

Department of Conservation v. Tate, 231 F. 2d 615

(4th Cir. 1955), aff’d 350 U. S. 877 .............................. 7-8

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202 ........................................ 10

Fayson v. Beard, 134 F. Supp. 379 (E. D. Tex. 1955) .... 8

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 ...................................... 6

Gilmore v. The City of Montgomery, 176 F. Supp. 776

(M. D. Ala. 1959), aff’d 277 F. 2d 364 (5th Cir.

1960) ................................................................................. 8

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U. S. 321 ................................ 10

Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission, 284 F. 2d 631

(4th Cir. 1960) ............................................................... 10

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 124 F. Supp. 290 (N. D. Ga.

1954), aff’d 223 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir. 1955), rev’d 350

U. S. 879 ........................................................................... 6, 8

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 6 1 .................................... 6, 8

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore City v. Dawson,

350 U. S. 877 ................................................................... 6, 9

PAGE

Moorhead v. City of Fort Lauderdale, 152 F. Supp. 131

(S. D. Fla. 1957), aff’d 248 F. 2d 544 (5th Cir.

1957) ................................................................................. 8

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Association, 347

U. S. 971, vacating and remanding 202 F. 2d 275 (6th

Cir. 1953) ......................................................................... 8

New Orleans City Park Improvement Association v.

Detiege, 252 F. 2d 122 (5th Cir. 1958), aff’d 358

U. S. 5 4 ............................................................................. 6, 7

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156

(5th Cir. 1957) .............................................................. 10

Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 U. S. 395 ................. 10

Shuttlesworth v. Gaylord, 202 F. Supp. 59 (N. D. Ala.

1961), aff’d 310 F. 2d 303 (5th Cir. 1962) ................... 8, 9

Smith v. Swormstedt, 16 How. (57 U. S.) 288 ............... 10

Stainback v. Mo Hock Ke Lok Po, 336 U. S. 368 ........... 7

State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey, 359 U. S. 533 .... 6

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 ....................... 6, 7

United States v. Corrick, 298 U. S. 435 ......................... 10

Ward v. City of Miami, Florida, 151 F. Supp. 593 (S. D.

Fla. 1957) ......................................................................... 8

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 ...................6, 7, 9

Willie v. Harris County, Texas, 202 F. Supp. 549

(S. D. Tex. 1962) ................ 8,9

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s

Federal Rule 23(a)(3) Pomeroy’s Equity Jurispru

dence (5th Ed. 1941 Symons), Vol. 1, §§260, 261 a-m .. 10

in

PAGE

In t h e

Isatprm? dmtrt rtf tlje United States

O c to ber T e r m , 1963

No. 663

C it y of N e w O r l e a n s , et al.,

—v.—

Appellants,

E v a n g e l in e B a r t h e , et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

MOTION TO DISMISS OR AFFIRM

Appellees, pursuant to Buie 16 of the Revised Rules of

the Supreme Court of the United States, move that this

appeal be dismissed on the ground that this Court lacks

jurisdiction, or that the final judgment and decree of the

District Court be affirmed on the ground that the questions

are so unsubstantial as not to warrant further argument.

Opinion Below

The opinion below is reported at 219 F. Supp. 788.

Statute

The statute declared unconstitutional by the District

Court is Section 33:4558.1 of the Revised Statutes of Louisi

ana of 1950.

2

Questions Presented

For the purposes of this motion, appellees adopt the

questions as presented by appellants at page 6 of their

Statement as to Jurisdiction and add the following:

Whether this Court has jurisdiction of this appeal?

Statement

This appeal is from the judgment of the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, en

tered on September 27, 1963, declaring unconstitutional

LSA-R.S. 33:4558.1, which requires racial segregation in

public parks and recreational facilities in the State of

Louisiana, and enjoining appellants from acting pursuant

thereto.

There is no dispute whatsoever that the park and recre

ational facilities and the entire recreational program of the

City of New Orleans are segregated on the basis of race.

This was admitted by the Director of the New Orleans

Recreation Department (NORD) as well as by the Super

intendent of the New Orleans Park and Parkway Commis

sion (R. 14, 49, 50). When the Director of NORD was

asked if this was the result of a law, custom, or policy

of the department, he replied:

Well, we consider it by law and by custom and by

policy of the depai'tment (R. 14).

There are ninety-five playgrounds for whites and nine

teen playgrounds for Negroes administered by NORD (R.

13). In addition, appellant New Orleans Parkway and Park

Commission administers two parks—one, Portchartrain,

for Negroes and another, West End, for whites (R. 48).

The Director of NORD testified that there was a need for

3

additional white and Negro playgrounds but that there was

a “bigger need” for Negro playgrounds (R. 43).

All of the recreational programs undertaken by NORD

are divided into white and Negro divisions (R. 23) and ad

ministered on a completely segregated basis (R. 14). Al

though the NORD director testified that all of the programs

available to whites are available to Negroes on a segre

gated basis except for the soap box derby, further testimony

from him and from the Negro recreational supervisor in

dicated that there was no NORD All-American baseball

league for Negroes, fine arts festival, charm school, bowl

ing activities, travel theatre, or civic orchestra (R. 32, 33,

99). NORD’s director contended that such things would be

provided for Negroes if they asked (R. 32, 33), but very

few NORD programs are initiated by this method (R. 99).

Advertising of programs is made on a racial basis (R. 21,

22). Of the two hundred fifty employees in the NORD pro

gram, fifty to sixty of them are Negro but none is in an

administrative position (R. 23).

The evidence contained a long procession of accounts of

denials, insults and discriminations against Negroes seek

ing to use white parks. A Negro who sought to enter the

soap box derby, the national winner of which receives a

college scholarship, was refused entrance on the basis of

race (R. 31, 76, 80, 81). One of the plaintiffs testified that

his son, a minor Negro plaintiff, Gary Burns, had com

peted in a NORD-sponsored track race, emerged the victor,

and then been ejected from the field, without his trophy,

because he was Negro (R. 66-71). A group of Negroes

playing baseball in the white Taylor Park was arrested even

though there was enough room for white and Negro young

sters to play (R. 83, 84, 86-89). Other Negroes playing

basketball were also arrested at Taylor Park (R. 90). The

charges against the latter group were dismissed when the

4

police did not show up for the trial (R. 91). Still other

Negroes were arrested or chased from public recreational

areas (R. 105, 106, 107, 109, 110). Moreover, several white

persons were refused permission to play golf on the all

Negro Portehartrain Park (R. 49, 50).

On or about June 8, 1962, approximately one thousand

Negroes, including the adult plaintiffs in this suit, submitted

a petition to the appellants, Mayor, Councilmen of the City

of New Orleans, and the Director of NORD, asking for

desegregation of the park and recreational facilities. The

same petition was submitted to the appellant New Orleans

Park and Parkway Commission on or about October 31,

1962. The facilities were not desegregated.

On September 27,1963, the lower court issued a judgment

declaring LSA-R.S. 33:4558.1 unconstitutional and enjoin

ing appellants from acting pursuant thereto. Appellants

subsequently filed this appeal. They also filed a notice of

appeal to the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit.

5

A R G U M E N T

I.

This Court Lacks Jurisdiction of This Appeal Because

No Three Judge Court Was Necessary for Disposition

Below. However, It Should Take Certiorari Jurisdiction

and Render Judgment on the Merits.

This case involves the validity of a state statute requiring

segregation in parks and recreational facilities in the State

of Louisiana. The statute, LSA-R.S. 33:4558.1, reads as fol

lows :

Separation of white and colored races

A. All public parks, recreation centers, playgrounds,

community centers and other such facilities at which

swimming, dancing, golfing, skating or other recrea

tional activities are conducted shall be operated sepa

rately for members of the white and colored races. This

shall not preclude mixed audiences at such facilities,

provided separated sections and rest room facilities are

reserved for members of white and colored races. This

provision is made in the exercise of the state’s police

power and for the purpose of protecting the public

health, morals and the peace and good order in the state

and not because of race.

B. “ Public” parks and other recreational facilities as

used herein shall mean any and all recreational facili

ties operated by the State of Louisiana or any of its

parishes, municipalities or other subdivisions of the

state.

C. Any person, firm or corporation violating any of

the provisions of this Section shall be deemed guilty of

6

a misdemeanor and upon conviction therefor by a court

of competent jurisdiction for each such violation shall

be fined not less than five hundred dollars nor more

than one thousand dollars, or sentenced to imprison

ment in the parish jail not less than ninety days nor

more than six months, or both, fined and imprisoned

as above, at the discretion of the court. Acts 1956,

No. 14, §§1-3.

Similar statutes and regulations have been repeatedly de

clared unconstitutional by this Court. Watson v. City of

Memphis, 373 U. S. 526; Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61;

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715;

State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey, 359 U. S. 533; New

Orleans City Park Improvement Association v. Detiege, 358

U. S. 54; Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903; Holmes v. City of

Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879; Mayor and City Council of Baltimore

City v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 877; Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U. S. 483; Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60.

It follows that a three judge court was not required in

this instance where “ prior decisions make frivolous any

claim that a state statute on its face is not unconstitutional.”

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31, 33; Turner v. City of

Memphis, 369 U. S. 350.1 Jurisdiction of this appeal is in

the Court of Appeals and not in this Court. Turner v. City

of Memphis, 369 U. S. 350, 353.

Nevertheless, appellees submit that there are compelling

reasons for this Court to treat the jurisdictional statement

as a petition for certiorari and to decide the issues on the

merits prior to judgment in the Court of Appeals. It is

1 In the instant ease the court below expressed doubt that a

three judge court was necessary but nevertheless decided the case.

The single district court judge who would otherwise have heard

the case also adopted the findings and conclusions as his own.

Barthe v. City of New Orleans, 219 F . Supp. 788, 789.

7

clear that this Court has such authority. 28 U. S. C. §§1254

(1), 2101(e); Turner v. City of Memphis, supra; Stainback

v. Mo Hock Ke Lok Po, 336 U. S. 368. The statute is plainly

unconstitutional and there is no dispute as to the facts. A

decision by this Court on the merits will serve the interest

of proper judicial administration by disposing of this liti

gation as expeditiously as possible and rendering extended

proceedings in the Court of Appeals unnecessary.

n.

The Questions Presented by Appellants Are Unsub

stantial.

This case presents once again the simple issue of whether

a state may exclude Negroes from public recreational facili

ties. There is no dispute that the facilities involved are

segregated. Such exclusion, based solely on race and color,

has been repeatedly condemned as a violation of the Four

teenth Amendment:

Discrimination in the use and enjoyment of public rec

reational facilities of any kind or nature owned and op

erated or owned and leased by the City, whether under

color of law, statute, ordinance, policy, custom, or

usage, is violative of the Equal Protection of the Laws

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States. Shuttlesworth v. Gaylord,

202 F. Supp. 59, 62 (N. D. Ala. 1961), aff’d 310 F. 2d

303 (5th Cir. 1962).

See also Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526; New

Orleans City Park Improvement Association v. Detiege,

252 F. 2d 122 (5th Cir. 1958), aff’d 358 U. S. 54 (outlawing

segregation in one park in New Orleans); Department of

Conservation v. Tate, 231 F. 2d 615 (4th Cir. 1955), aff’d

8

350 U. S. 877; Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Associ

ation, 347 U. S. 971, vacating and remanding 202 F. 2d 275

(6th Cir. 1953); Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 124 F. Supp. 290

(N. D. Ga. 1954), aff’d 223 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir. 1955), rev’d

350 U. S. 879; Gilmore v. The City of Montgomery, 176 F.

Supp. 776 (M. D. Ala. 1959), aff’d 277 F. 2d 364 (5th Cir.

1960); City of St. Petersburg v. Alsup, 238 F. 2d 830 (5th

Cir. 1956); Moorhead v. City of Fort Lauderdale, 152 F.

Supp. 131 (S. D. Fla. 1957), aff’d 248 F. 2d 544 (5th Cir.

1957); City of Greensboro v. Simkins, 149 F. Supp. 562

(M. D. N. C. 1957), aff’d 246 F. 2d 425 (4th Cir. 1957);

Brown v. South Carolina State Forestry Comm., ------ F.

Supp.------ (No. 774, E. D. S. C. July 10, 1963); Bohler v.

Lane, 204 F. Supp. 168 (S. D. Fla. 1962); Willie v. Harris

County, Texas, 202 F. Supp. 549 (S. D. Tex. 1962); Ward

v. City of Miami, Florida, 151 F. Supp. 593 (S. D. Fla.

1957); Fayson v. Beard, 134 F. Supp. 379 (E. D. Texas

1955).

Moreover, these cases are no more than specific applica

tions of the broader principles that public facilities may not

be segregated, Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61, and that

discriminatory classification based exclusively on color does

not meet constitutional commands. Burton v. Wilmington

Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715.

Despite this long line of cases, appellants seek a reversal

of the decision of the lower court on the grounds that (1)

LSA-E.S. 33:4558.1, which requires segregation of the races

in parks and recreational facilities, is a valid exercise of

the state’s police power, (2) appellees have not shown that

this is a proper class action, and (3) no preliminary injunc

tion should have issued. None of these arguments is novel.

All have been rejected expressly and by implication in pre

vious cases, cited herein.

9

Appellants seek to use the police power of the state to

justify racial segregation. As long ago as Buchanan v.

Warley, 245 U. S. 60, this Court decided that the police

power could not be so used. That case, like tills, involved

the constitutionality of a statute requiring segregation. In

the action for the specific performance of a contract to buy

a house, the Negro defendant contended that the contract

terms had not been met because the ordinance prevented his

occupancy of the house. Rejecting an argument that the

statute was a proper exercise of the state’s police power,

this Court stated (at page 74):

The authority of the state to pass laws in the exercise

of the police power, having for their object the promo

tion of the public health, safety and welfare, is very

broad, as has been affirmed in numerous and recent de

cisions of this court . . . But it is equally well estab

lished that the police power, broad as it is, cannot jus

tify the passage of a law or ordinance which runs

counter to the limitations of the Federal Constitution.

Similarly, the argument was rejected last term in Watson

v. Memphis, supra, in which it was argued that the state’s

obligation to prevent violence and disorder justified a delay

in the desegregation of the recreational facilities of Mem

phis, Tennessee. See also Dawson v. Mayor and City Coun

cil of Baltimore City, supra, 220 F. 2d at 387; Shuttlesworth

v. Gaylord, supra, 202 F. Supp. at 62; Bohler v. Lane, supra,

at 173.

Equally untenable is the argument that no foundation

was laid to show a proper class action. All of the recrea

tion cases cited herein were class actions brought in the

same manner as this case. As stated in Willie v. Harris

County, Texas, supra, 202 F. Supp. 549, 555:

10

But this court is not familiar with any principle which

would prevent relief from extending to all members

of the class similarly situated with the plaintiffs. The

operation of the park on a segregated basis is admitted

—the wrong extends to the entire class of which the

plaintiffs are representative, and it is plainly within

the sound discretion of this court to grant relief coter

minous with the wrong.

See also Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202; Orleans Parish

School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156, 165 (5th Cir. 1957).

Cf. Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294; Hecht

Co. v. Bowles, 321 U. S. 321, 329; Porter v. Warner Hold

ing Co., 328 U. S. 395, 398. Federal Rule 23 (a) (3) was

intended to deal with just such situations in order to avoid

a multiplicity of actions. Cf. Pomeroy’s Equity Jurispru

dence (5th Ed. Symons 1941), Vol. 1, §§260, 261 a-m;

Smith v. Swormstedt, 16 How. (57 U. S.) 288.

The lower court’s decision to grant a preliminary injunc

tion cannot be disturbed without a showing of a clear abuse

of discretion. United States v. Corrick, 298 U. S. 435, 437.

Appellants, however, have made no such showing. Instead

they contend that the appellants are “high class men” and

that there is no showing that they would disobey the lower

court’s ruling that LSA-R.S. 33:4558.1 is unconstitutional.

But appellees were entitled to relief by preliminary injunc

tion from the moment they established that their constitu

tional rights were being violated. Henry Greenville Airport

Commission, 284 F. 2d 631 (4th Cir. 1960); Clemons v.

Board of Education of Hillsborough, 228 F. 2d 853, 857

(6th Cir. 1956); Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State

University v. Wilson, 340 U. S. 909.

Appellants could not make a showing of abuse of discre

tion given the uncontradicted evidence of their discrimina

11

tory practices. Facilities and programs were maintained

on a racially segregated basis “ by law and by custom and

by policy of the department” (R. 14). Only nineteen play

grounds wrere available to Negroes as opposed to ninety-five

for whites (R. 13). Negro facilities were “by no means

equal to those available to white persons.” Barthe v. City

of New Orleans, 219 F. Supp. 788, 789. Many programs

available to whites were unavailable to Negroes, including

the soap box derby, the NORD All-American Baseball

League, fine arts festival, charm school, bowling activities,

traveling theatre, and civic orchestra (R. 31, 32, 33, 99).

Program advertising was on a racial basis (R. 21, 22).

Employment was rigidly segregated and no Negro was in

an administrative position (R. 23). Witness after witness

testified to insulting denials of the use of white facilities:

at least one park was closed (R. 25, 26); one boy was ejected

from a field without his trophy after winning a race (R. 66,

71); another could not compete for a college scholarship

in the soap box derby (R. 76, 80, 81); and many Negroes

were arrested while playing on white facilities (R. 83, 84,

86, 88, 89-91,105-107,109-110).

Thus the lower court was entirely justified in issuing

its order for preliminary injunction. In doing so it simply

followed long-standing precedents in which similar relief

had been given. See cases cited at pages 7, 8, supra.

12

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that this Motion to Dismiss or Affirm should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

J a m e s M . N a b r it , III

G eorge B. S m i t h

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

E r n e s t N. M o r ia l

A. P . T u r e a u d

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellees

3 8