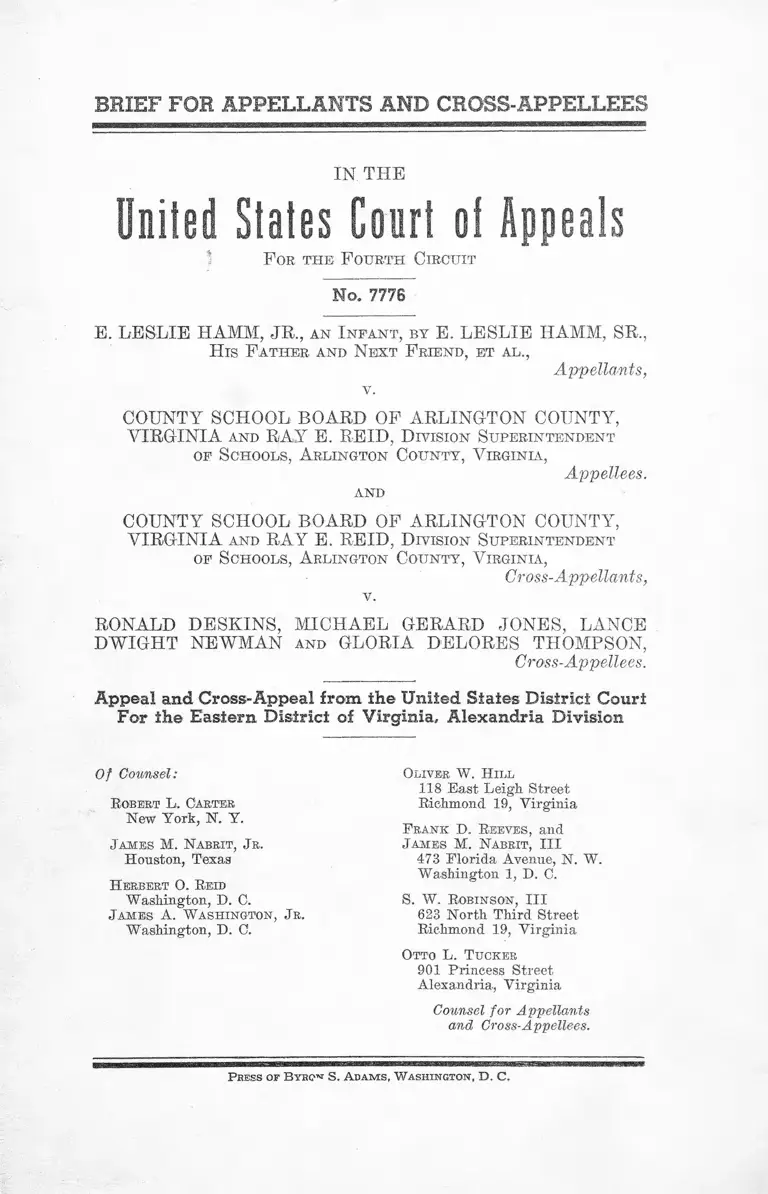

Hamm v. Arlington County, VA School Board Brief for Appellants and Cross-Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hamm v. Arlington County, VA School Board Brief for Appellants and Cross-Appellees, 1958. 8812da4c-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/01ccaf3b-12e7-463c-99fe-49062aa45773/hamm-v-arlington-county-va-school-board-brief-for-appellants-and-cross-appellees. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

BRIEF FOB APPELLANTS AND CROSS-APPELLEES

IN TH E

Dni led S t a t e s Cour t oi Appea l s

1 F ob t h e F ourth C ircuit

No. 7776

E. L E SL IE HAMM, JR ., an I n f a n t , by E. L E SL IE HAMM, S R ,

His F a th er and N ex t F rien d , e t a h ,

Appellants,

v.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF ARLINGTON COUNTY,

VIRGINIA and RAY E. REID , D iv ision S u per in ten d en t

of S chools, A rlington Co u n ty , V ir ginia ,

Appellees.

a n d

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF ARLINGTON COUNTY,

V IRGINIA and R A Y E. REID, D ivision S u per in ten d en t

of S chools, A rlington Co u n ty , V ir ginia ,

Cross-Appellants,

v.

RONALD DESKINS, M ICHAEL GERARD JONES, LANCE

DW IGHT NEWMAN and GLORIA DELORES THOMPSON,

Cross-Appellees.

Appeal and Cross-Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Eastern District of Virginia, Alexandria Division

Of Counsel:

Robert L. Carter

New York, N. Y.

J ames M. Nabr.it, J r.

H ouston, Texas

H erbert O. Reid

W ashington, D. C.

J ames A. Washington, J r.

W ashington, I). C.

Oliver W. H ill

118 E as t L eigh S treet

Biehmond 19, V irg in ia

F rank D. Beeves, and

J ames M. Nabrit, I I I

473 F lo rid a Avenue, N . W.

W ashington 1, D, C.

S. W. Bobinson, I I I

623 N orth T h ird S treet

Biehmond 19, V irg in ia

Otto L . T ucker

901 Princess S treet

Alexandria., V irg in ia

Counsel fo r Appellants

and Cross-Appellees.

P ress of B yrc™ S . A d a m s , W a s h in g t o n , D . C .

Statement of the Case

INDEX

Page

. 1

Questions Presented .............................................. 3

Statement of the Facts:

I. Prior Proceedings................................................. 4

II. Statement of Facts on the Instant A ppeal......... 7

III. Historical Background .................................. .. 14

Argument:

I. The manner in which appellees acted upon ap

pellants applications for admission to “ white”

schools is racial discrimination in contravention

of appellants constitutionally guaranteed rights

to due process and equal protection of the laws .. 18

II. The court below erroneously considered appellees’

rejection of appellants applications for admission,

enrollment and education in designated “ white”

schools as “ administrative determinations” to be

reviewed pursuant to the “ substantial evidence”

doctrine and, having thus limited its scope of in

quiry, failed to discharge its obligation to make

an independent evaluation and determination of

the facts decisive of appellants’ constitutional

claim that their exclusion from said schools was

because of race or co lo r...................................... 28

III. Review and consideration of the Available and

pertinent evidence compels the conclusion that the

reasons advanced by appellees for their rejection

of appellants’ applications for admission, enroll

ment and education in “ white” schools were

based upon considerations of race or color in con

travention of appellants’ constitutionally guaran

teed rights of due process and equal protection

and in violation of the prior orders of the court .. 33

Response to appellee’s cross-appeal.................... 39

11 Index Continued

IV. The court’s previous judgment, affirmed on ap

peal, that five appellants were qualified for and

could not be refused admission to designated

“ white” schools, may not be nullified, in subse

quent proceedings for its enforcement, on the

ground of appellants’ alleged disqualification for

reasons available to but not urged by appellees

in the prior proceedings...................................... 41

V. The court below erred in postponing until the

second semester of the school session of 1958-59,

the effective date of its order restraining and en

joining appellees from refusing to admit four of

appellants in the “ white” school from which they

Page

had been improperly excluded ........................... 45

Conclusion ..................................................................... 50

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases :

Aaron v. Cooper, F.2d , (8th Cir. No. 16094,

10 November 1958) .............................................. 26,35

Adkins v. School Board of the City of Newport News,

148 F. Supp. 430 (E.D.Va. 1957), aff’d 246 F.2d

325 (4th Cir. 1957) ................................................. 15

Baltimore & Ohio RR Co. v. United States, 298 U.S.

349 (1936) .............................................................. 32

Baltimore S.S. Co. v. Phillips, 274 U.S. 316 (1927) 42

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) .................... 24

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ;

349 U.S. 294 (1955) ................................... 24,34,47,49

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917) ............. 24,26

Carter v. School Board of Arlington County, 182 F.

2d 531 (4th Cir. 1950) .......................................... 39

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 (1950)........................ 26

Child Labor Tax Case, 259 U.S. 20 (1922) ............. 21

City and Town of Beloit v. Morgan, 74 U.S. (7 Wall.)

619 (1869)........................... 42

Clemmons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, Ohio,

228 F. 2d 853 (6th Cir. 1956), cert den. 350 U.S.

1006 (1956) ..................................................... 35,49,50

Chicot County Drainage Dist. v. Baxter State Bank

308 U.S. 371 (1940) ............................................. 43

C. I. R. v. Sunnen, 333 U.S. 591 (1948) ................ 43

Index Continued iii

Page

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) . . . .24, 34, 45, 48, 49

Cromwell v. Sac County, 94 U.S. 351 (1877) ......... 42

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S.D. Ala., S.D.

1949) ...................................................................... 21

Dowell v. Applegate, 152 U.S. 327 (1894) ................ 42

Ex Parte Endo, 323 U.S. 283 (1944) .....................24,38

Feiner v. New York, 340 U.S. 315 (1951) ................ 33

Gould y. Evansville & C. R. Co., 91 U.S. 526 (1876) 43

Grubb v. Public Utilities Commission of Ohio, 281

U.S. 470 (1930) ..................................................... 43

Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400 (1942) ........................... 26

Hooven & Allison Co. v. Evatt, 324 U.S. 652 (1945) 32

Hopkins v. Lee, 19 U.S. (6 Wheat.) 109 (1821) . . . . 43

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944) .. 23

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939) ........................23, 25

Maggio v. Zeitz, 333 U.S. 56 (1948) ........................ 43

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501 (1946) ................ 32

McCullough v. Virginia, 172 U.S. 102 (1898) ......... 44

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 948 (4th Cir.

1951), cert. den. 341 U.S. 951 (1951) ................ 38,49

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637

(1950) .................................... ........................ 24,44,47

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923) ................. 38

Morgan v. United States, 304 U.S. 1 (1938) ......... 30

NAACP v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 (E.D.Va. 1958) 15

National Labor Relations Board v. Babcock & Wilcox

Co., 351 U.S. 105 (1956) ...................................... 39

Ng Fung Ho v. White, 259 U.S. 276 (1922) ............. 32

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268 (1951) ......... 33

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U.S. 536 (1927) ................ 24

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) ................ 32

Ohio Valley Water Co. v. Ben Avon Borough, 253

U.S. 287' (1920) .......................................... ' ......... 32

Oriel v. Russell, 278 U.S. 358 (1929) ........................ 43

Perry v. Cyphers, 186 F. 2d 608 (5th Cir. 1951) . . . . 26

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925) . . . . 38

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354 (1939) .............33,49

Radio Corp. of America v. United States, 341 U.S.

412 (1951) ........................................... ................. 39

Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387 (4th Cir. 1947), cert.

den. 333 U.S. 875 (1948) ...................................... 26

Secretary of Agriculture v. Central Roig Refining

Co., 338 U.S. 604 (1950) ....................................... 39

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948)...................25, 45

IV Index Continued

Sibbald v. United States, 37 U.S. (12 Pet.) 488 (1838) 42

Sipnel v. Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631 (1948) . .24, 47

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942) ............. 24

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944) ................. 26

Smith v. Cahoon, 283 U.S. 553 (1931) .................... 23

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) ........................ 26

Sonthern. Garment Mfr’s. Ass’n v. Fleming, 122 F

2d 622 (D.C. Cir. 1941) ........................ . . . . . . . 30

Sparrow v. Strong, 70 U.S. (3 Wall.) 97 (1866)__ 21

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R.R. Co., 323 U.S

192 (1944) .............................................................. 23

St. Joseph Stock Yards Co. v. United States, 298

Page

U.S. 38 (1936) ............................................. . 32

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) ................ 24,47

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953) .................... 26

The Haytian Republic, 154 U.S. 118 (1894) ............. 42

Thompson v. School Board of Arlington County, 144

F. Supp. 239 (E.D.Va. 1956), aff’d, 240 F. 2d 59

(4th Cir. 1956), cert. den. 353 U.S. 910 (1957) ;

159 F. Supp. 567 (E.D.Va. 1957), aff’d, 252 F. 2d

929 (4th Cir. 1958), cert. den. 356 U.S. 958

(1958) ..............................................................2, 5, 6, 25

United States v. Munsingwear, Inc., 340 U.S. * 36

(1950) ......................................... 43

United States v. Peters, 9 U.S. (5 Cranch) 115

(1809) ............................................................. 44

Washington Bridge Co. v. Stewart, 44 U.S. (3 How )

413 (1845) ................................................ 42

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U.S. 49 (1949) ....................21 32

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) . .24, 34, 36,’ 37

S outhern* S chool N e w s :

Vol. 2, No. 8, Feb. 1956, p. 1 4 .................................. 15

Vol. 2, No. 9, March 1956, p. 1 4 ........... 16

Vol. 2, No. 10, April 1956, p. 13 ......................” ” 17

Vol. 2, No. 12, June 1956, p. 1 3 ............................... 18

IN THE

Uni ted S t a t e s Cour t oi Appeals

F ob t h e F ourth Circuit

No. 7776

E. LE SL IE HAMM, JR ., an I n f a n t , by E. L E SL IE HAMM, SR.,

His F a th er and N ex t F rien d , et a l .,

Appellants,

v.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF ARLINGTON COUNTY,

VIRGINIA and RAY E. REID , D iv ision S u per in ten d en t

of S chools, A rlington Cou n ty , V ir ginia ,

Appellees.

and

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF ARLINGTON COUNTY,

VIRGINIA and RAY E. REID , D ivision S u p er in ten d en t

of S chools, A rlington Cou n ty , V ir ginia ,

Cross-App ellants,

v.

RONALD DESKINS, M ICHAEL GERARD JONES, LANCE

DW IGHT NEWMAN and GLORIA DELORES THOMPSON,

Cross-Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS AND CROSS-APPELLEES

Appeal and Cross-Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Eastern District of Virginia, Alexandria Division

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On 31 July 1956 the court below entered an Order of

Injunction restraining and enjoining appellees from refus

ing on account of race or color to admit, enroll and educate

in any school under their operation, control, direction or

supervision (i.e. the public schools of Arlington County,

Virginia) any child otherwise qualified. A Supplemental

2

Decree of Injunction entered by the court below on 14

September 1957, restrained and enjoined appellees from

refusing to admit, enroll and educate these seven children

in the schools to which they had applied, effective 23 Sep

tember 1957. Both of these prior judgments were affirmed

on previous appeals to this Court, and petitions for writs

of certiorari were denied.

The instant and third appeal in this case is from the

Supplementary Order of Injunction entered by the court

below on 22 September 1958, upon appellants’ complaint

in intervention and motion for further relief under the

prior orders, in which the court (i) approved, as being

based upon valid evidence of disqualification and untainted

by considerations of race or color, appellees’ rejection of

the applications by twenty-five appellants, including five

of the seven previously ordered admitted, for admission

to designated “ white” schools; and (ii) delayed until the

commencement of the second semester of the current school

term, the effective date of its decree insofar as it restrained

and enjoined appellees from refusing to admit, enroll and

educate four of the appellants in the “ white” Stratford

Junior High School, the rejection of whose applications

by appellees the court found unjustified by the evidence.

The appellees have filed a cross-appeal from the order

of the court below restraining and enjoining them from

refusing to admit the four appellants in Stratford Junior

High School, and a separate brief in connection with that

cross-appeal. In lieu of a separate responsive brief, a

designated portion of this brief, infra, is addressed to

the issues presented by the cross-appeal.

The previous decisions in the instant case have been

reported sub nom., Thompson v. School Board of Arlington

County as follows: 144 F. Supp. 239 (E.D. Va. 1956),

aff’d, 240 F. 2d 59 (4th Cir. 1956), cert. den. 353 U.S. 910

(1957); 159 F. Supp. 567 (E.D. Va. 1957), aff’d, 252 F. 2d

929 (4th Cir. 1958), cert, den., 356 U.S. 958 (1958). The

opinion of the court below is reported at 166 F. Supp. 529

and included in the Joint Appendix herein at pp. 11-24.

3

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The questions presented on this appeal are as follows:

1. Whether appellees’ action in refusing to admit, enroll

and educate appellants in the “ white” schools to which

they applied, on the basis of appellees ’ ex parte determina

tion, that appellants were not qualified for admission, en

rollment and education in said schools by the application

of standards not similarly applied to white pupils admitted,

enrolled and educated in the same schools, contravened

appellants’ rights to due process and equal protection of

the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment.

2. Whether the court below erred in failing and refusing

to exercise its independent judgment on those issues of

fact which were decisive of appellants’ claim that appellees

refused, on account of race or color and in contravention

of appellants’ constitutional rights, to admit, enroll and

educate appellants in the “ white” schools for which they

applied.

3. Whether the court below erred in failing and refusing

to hold, upon the available and pertinent evidence, that the

reasons advanced by appellees for their rejection of appel

lants’ applications for admission, enrollment and education

in the schools to which they had applied were based upon

considerations of race or color in contravention of appel

lants’ constitutionally guaranteed rights of due process

and equal protection dnd in violation of the prior orders

of the court.

4. Whether five appellants, previously found by the

court to be qualified and ordered admitted and enrolled

in designated “ white” schools, can now be refused admis

sion and enrollment in said schools, after appeal and

affirmance of the court’s order, on the basis of their alleged

disqualification for reasons available to but not urged by

appellees until said appellants sought enforcement of the

prior order in the proceedings below".

5. WThether the court below erred in postponing, until

the commencement of the second semester of the 1958-1959

4

school term (2 February 1959), the effective date of its

order, entered (22 September 1958) two weeks after the

beginning of the first semester (8 September 1958), re

straining and enjoining appellees from refusing to admit,

enroll and educate four appellants in the “ white” schools

from which they unlawfully had been excluded.

These questions are raised in the record by the court’s

Supplementary Order of Injunction entered 22 September

1958 (JA 224), based upon its Findings of Fact and Con

clusions of Law entered 17 September 1958 (JA 11-24),

denying the relief sought in the Motion for Further Relief,

filed 26 August 1958 (JA 1-5) in behalf of eight of the

present appellants then parties to the suit (A, B, C, D, E,

1, 13, and 22),1 and the Complaint in Intervention, filed

26 August 1958 in behalf of twenty-two Negro children

not theretofore parties (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 14, 15,

16, 17,2 18, 19, 20, and 21).

STATEM ENT OF THE FACTS

The consideration and determination of this appeal

requires a review of the background and prior proceedings

in this case, as follows:

I. PRIOR PROCEEDINGS

On 31 July 1956, the court below, acting upon the com

plaint of plaintiff Negro children of school age resident

in Arlington County, Virginia, and their parents or

guardians, for themselves and others similarly situated,

entered the following Order Granting Injunction (R.

179, 181) :

. . . A djudged , Ordered, an d D ecreed th a t effective

a t th e tim es a n d su b jec t to th e co n d itio n s h e re in a f te r

1 Throughout the testim ony, the exhibits and the c o u rt’s F ind ings of F a c t

and Conclusions of Law, the indiv idual pupil-p lain tiffs are referred to by

letters , iden tify ing those who were ordered adm itted to designated “ w h ite”

schools in Septem ber 1957, and by num bers iden tify ing those whose admission

to designated ‘ ‘ white ’ ’ schools was before the court fo r th e first tim e. The

nam es of these individual p lain tiffs1 a re re la ted to the le tte rs and num bers

in a “ Code fo r Spot M ap s” ( JA 284-285.)

2 This p la in tiff has le f t th e ju risd ic tion and, therefore, is no t included

am ong the p resen t appellants.

5

stated, the defendants, their successors in office, agents,

representatives, servants and employees be, and each

of them is hereby, restrained, and enjoined from re

fusing on account of race or color to admit to, or

enroll or educate in, any school under their operation,

control, direction, or supervision any child otherwise

qualified for admission to, and enrollment and educa

tion in, such school.

# # # #

. . . the injunction hereinbefore granted should be,

and it is hereby made, effective in respect to elementary

schools at the beginning of the second semester of the

1956-1957 session, to wit, January 31, 1957, and in

respect to junior and senior high schools at the com

mencement of the regular session for 1957-1958 in

September 1957.

This judgment was affirmed by this Court on 31 December

1956 (R. 188). Writ of certiorari was denied 25 March

1957. See 353 TI.S. 910.

No Negro pupils having been admitted to or enrolled

in the theretofore white schools pursuant to this judgment,

on 29 July 1957, the court below entered an order on

plaintiffs’ motion to amend the original decree, as follows

(R, 206):

That the injunction specified in said judgment become

in respect to both elementary and secondary schools

effective at the commencement of the regular school

term for 1957-1958 commencing in September 1957.

On 4 September 1957, the court below, in granting plain

tiffs’ motion for further relief, found that

Seven Negro children of school age were refused

admission as pupils in the public schools of Arlington

County, Virginia on the opening day of the current

session. . . . (R. 239)

# # * #

Nothing in the evidence indicates that any of the

plaintiffs is not qualified in his studies to enter the

school which he sought to enter . . . Anyway, no

6

intimation of disqualification appeared as to any ap

plicant. (R. 243-244)

A review of the evidence is convincing that the only

ground . . . for the rejection of plaintiffs was that they

were of the Negro race. The rejection was simply

the adherence to the prior practice of segregation.

No other hypothesis can be sustained in any of the

seven instances. . . . (R. 244)

Whereupon, on 14 September 1957, the court below entered

a Supplemental Decree of Injunction, as follows (R. 248-

249) :

Ordered th a t th e d e fen d an ts , th e ir su ccesso rs in

office, a g e n ts , re p re s e n ta tiv e s , s e rv a n ts , a n d em ployees

be, and each of th em is h e reb y r e s tr a in e d a n d en jo in ed

fro m re fu s in g to ad m it th e sa id m o v an ts to , o r en ro ll

a n d ed u ca te th em in, th e sa id schools to w hich th e y

h av e m ad e a p p lic a tio n fo r ad m issio n , th a t is :

# # # *

3. Robert A. Eldridge III in the Fillmore School or

the Patrick Henry School;

4. Oeorge Tyrone Nelson in the Stratford Junior

High School; or the Swanson Junior High School;

5. E. Leslie Hamm, Jr. in the Stratford Junior

High School or the Swanson Junior High School;

6. Louis George Turner in the Swanson Junior High

School;

7. Melvin H. Turner in the Swanson Junior High

School; upon the presentation by the said movants of

themselves for admission, enrollment and education

in the said schools commencing at the opening of said

schools on the morning of September 23, 1957.

This injunction was suspended pending appeal (R. 256)

and, on 12 February 1958, was affirmed by this Court (R.

399). Writ of certiorari was denied 19 May 1958. See

356 H.S. 958.

Against this background, we present the factual basis

for the instant appeal.

7

II. STATEMENT OF FACTS ON THE INSTANT APPEAL

Subsequent to the close of the 1957-58 school term, appel

lants, Negro pupils attending the Arlington County, Vir

ginia, public schools, through their parents and guardians,

applied to the appellees, the School Board and the Division

Superintendent of Schools of Arlington County, Virginia,

for admission and enrollment at the commencement of the

next school term on 4 September 1958 in designated schools

theretofore maintained exclusively for white students, “ or

to such other school his [or her] assignment to which may

properly be determined on the basis of objective considera

tions without regard to his [or her] race or color.” This

group of thirty pupils included five of the seven students

who had been ordered admitted to designated schools by

the Supplemental Order of Injunction entered by the court

belowT on 14 September 1957, supra.

The parents or guardians of each of these infant appel

lants received a letter dated 7 August 1958 from the Pupil

Placement Board of the Commonwealth of Virginia request

ing that they appear with their children for personal

interviews to be conducted by that agency [PL Ex. 7,

T. 359]. All declined to attend the interviews, but they

again requested the appellees to assign their children in

accordance with their previous requests, offering to co

operate in furnishing necessary information to appellees

[Def. Ex. 13, T. 356]. Subsequently, the appellees and

the Pupil Placement Board jointly summoned the appel

lants to personal interviews [PI. Ex. 8, T. 359]. Each of

the pupils, accompanied by one or both parents, attended

one of the interviews which wrere conducted jointly by the

state and local authorities on 18, 19, and 29 August 1958,

and each applicant was subsequently notified by appellees

that their requests (for assignment to ‘‘white’’ schools)

had been denied by the Pupil Placement Board.

On 26 August 1958, twenty-two of the applicants who

had not previously been parties to this action filed a Com

plaint in Intervention (E. 408), which complaint, as did

the Motion for Further Belief simultaneously filed in be

8

half of the eight applicants already parties herein (JA 1-5),

prayed for specific injunctive relief in enforcement of

the previous orders entered herein. On the same day

appellees filed a Report and Request for Guidance, describ

ing the course of events subsequent to the filing of the

Mandate and Opinion of this Court on the previous appeal,

and stating that they intended to make no assignments of

the appellants unless directed to do so by the court below

(JA 6-9).

On the evening of 28 August 1958, having studied and

familiarized themselves, upon advice of counsel, with sum

maries of data prepared from the cumulative folders of

each of the appellants, appellee School Board met in closed

session and, after discussion, determined that the appli

cations submitted by appellants fell into five different prob

lem areas on the basis of which, by vote of appellee School

Board, each of the applications would be rejected if the

court should determine that appellees had the legal re

sponsibility for assigning appellants to Arlington County

public schools (JA 43-44). Appellees’ “ proposed” rejec

tion of appellants’ applications for admission to “ white”

schools and the reasons therefor were first disclosed to

appellants and the public on 2 September 1958 at the

hearing before the court below. {Ibid.)

The five problem areas into which appellants’ applica

tions fell and on the basis of which all were rejected by

appellee School Board were described as follows: I. At

tendance Area; II Overcrowding at Washington and Lee

High School; III Academic Achievement; IV Psycho

logical Problems; and V Adaptability {Ibid.).

The procedure followed by appellees in the consideration

and rejection of appellants’ applications, was a procedure

developed and used only with respect to those pupils who

sought to enter schools attended by pupils of the opposite

race (JA 32, 74-78).

The evidence presented at the hearing with specific

reference to appellees’ consideration of each of the afore

9

mentioned problem areas as reasons for rejecting appel

lants’ applications is as follows:

Attendance Area

Rejection of the applications of eleven appellants (2, 3,

4, 9, 14, 15, 17, 18, 23, 24, 25) was voted by appellee School

Board on the basis of problems related to attendance area

(JA 44-49). These eleven pupils were residents of the

attendance area prescribed for the Hoffman-Boston School,

and were reassigned by the Pupil Placement Board and

appellees to that school. The Hoffman-Boston School has

heretofore enrolled and now enrolls Negro pupils only

(JA 90-91, 99-100), and houses both elementary and sec

ondary grades. The boundaries of this attendance area

were established prior to this litigation (JA 90), and for

the specific purpose of serving the Negro pupils within

its confines (R. 374). The portion of Arlington County

embraced by the Hoffman-Boston attendance area bound

aries is occupied almost exclusively by Negroes, but the

few white pupils residing therein are assigned to schools

other than Hoffman-Boston (JA 91-92, 142-146).

Four of the pupils affected by this reason for rejection

are high school students seeking admission to Wakefield

School. For high school zoning purposes, the Hoffman-

Boston area forms an elongated enclave within the Wake

field (“ white” ) attendance area (Def. Ex. 7, T. 101). The

seven remaining pupils sought admission to Kenmore,

Gfunston, and Thomas Jefferson (“ white” ) Junior High

Schools. These schools are located closer to their respec

tive residences than Hoffman-Boston, the latter school

being located at one end of the district and their residences

at the other end (Def. Ex. 6, T. 101).

Each of the rejections based upon Attendance Area was

approved by the court below.

Overcrowding at W ashington and Lee High School

Five pupils (D, 1, 12, 19, 21) were denied assignment to

the Washington and Lee (“ white” ) High School on the

10

ground that Washington and Lee was overcrowded (JA

50, 53). These students are residents of an area referred

to as the North Hoffrnan- Boston area. This area which

was entirely surrounded by the Washington and Lee at

tendance area, and was widely separated from the Hoffman-

Boston school and Hoffman-Boston attendance area above-

described, was reported to have been abolished for assign

ment purposes by the appellee School Board at the same

meeting at which the appellee School Board considered and

rejected appellants’ applications. The area was made

a part of the Washington and Lee attendance area for

high school students and a part of the Stratford attendance

area for junior high school students (JA 46, 48).

For the 1958-59 school term Washington and Lee had

a planned enrollment of 2600 and a capacity of 2000;

Wakefield had a planned enrollment of 2540, with a capacity

of 2000; and Hoffman-Boston had a combined elementary

and secondary enrollment of 575, with a capacity of 375,

increased by 100 through the use of temporary facilities,

and with facilities for 100 more students under construc

tion and estimated for completion in January 1959 (PI.

Ex. 5, JA 225).

In a prior action unrelated to appellants’ request for

admission to Washington and Lee, the appellee School

Board had assigned all 10th grade students residing in the

northwestern sector of the Washington and Lee attend-

and area, numbering 250, to attend the Wakefield School,

in order to equalize the burden of overcrowding between

Washington and Lee and Wakefield, pending completion

of a proposed new high school (JA 50-51). The area from

which these 250 white 10th grade students were siphoned-

off from Washington and Lee to Wakefield abuts but

does not embrace the “ abolished” North Hoffman-Boston

attendance area where the affected appellants reside (JA

53). The five affected appellants, four of whom were

10th grade students, were assigned to the Hoffman-Boston

School.

11

The court below approved this reason as the basis for

rejection of these five requests for assignment to Washing

ton and Lee, or other appropriate “ white” high school.

Academic Achievement

Twenty-two appellants (B, C, D, E, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10,

11, 12, 14, 15, 17, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25) were refused admission

and enrollment, in “ white” schools on the basis of academic

accomplishment (JA. 54-62). These included all of the

pupils rejected for reasons of Attendance Area and Over

crowding except for Nos. 1, 18, and 19, in addition to nine

others not previously mentioned.

The data used by the Board in connection with this reason

for rejection consisted of the latest available scores at

tained by the appellants on the California Achievement

Test. This test is given annually in the county schools to

children in grades 3, 5, 7, and 9 (JA 54). The individual

pupil’s test scores were compared with statistical data indi

cating the median achievement levels of typical junior and

senior high school classes at Ho f'f man -Boston (Negro)

School, and with similar data for Stratford Junior High

and Washington and Lee Senior High (white) Schools.

This data indicated that in the two all-white schools seventy

percent of the pupils scored above the national norm,

while at Hoffman-Boston only twenty percent of the

students scored above the national norm (JA 56). In

Arlington County the median score at the white schools

ranged above and at the Negro school below the national

norm (JA 55).

The applicants who had scored below the national norm

and who, consequently, fell below the median score of the

typical class at the white school to which they applied

were rejected. The scores of these applicants fell within

the lower one-third of the typical white class to which they

were seeking admission (JA 116).

An expert witness called by appellants testified that the

California Achievement tests are extremely limited as a

means of determining the proper grade placement of pupils

12

(JA 148) ; that the national norm published by the authors

of the test does not represent a minimum standard of

achievement for pupils in a particular grade because fifty

percent of all pupils will score above and fifty percent

below this median score or national norm (Ibid.) • and

that within any typical class of a given grade tested,

there would normally be a variation of scores within the

middle sixty percent of such class of two to three years

in grade equivalent (JA 148-149). This witness concluded

that, upon examination of the school records of the appel

lants, all but three of them scored within the range of

achievement of this middle sixty percent (JA 167), and

were qualified for advancement to the next grade in any

school (JA 153-166) ; and that the three students who

scored within the bottom twenty percent probably needed

remedial work (JA 167-171). The witness stated that in

his opinion the gap between the achievement of pupils in

segregated Negro and white schools tended to increase with

the passage of time, and thus to be greater in the higher

than in the lower grades (JA 171).

The court below approved the rejections based upon the

Academic Achievement reason and the consequent assign

ment of these appellants to Hoffman-Boston School.

Psychological Problems

Seven appellants (C, 1, 2, 6, 8, 21, 24) who were also

disqualified for admission to the “ white” schools they

sought to enter for one or both of the reasons described

above, where rejected because of alleged psychological

problems (JA 65). The appellee School Board explained

that it had relied upon the conclusions of the State Di

rector of Psychological Services, which conclusions were

based upon his examination of appellants’ school records.

He did not testify, but the report he submitted to the

appellee School Board stated that the records of the pupils

discussed evidenced such things as “ instability”, “ lack

of self-control” , “ extreme shyness” , etc., and he con

cluded that it would be unwise to subject these pupils to

the pressures of attending a school with children of another

13

race (JA 64-65 and Def. Ex. 10, JA 286). Accordingly,

these appellants would remain at Hoffman-Boston School.

An expert witness called by appellants testified that there

was insufficient data in the School Board’s cumulative

records on the individual pupils to justify any clinical

judgment with respect to their psychological problems

(JA 211-213), but that, on the evidence available, conclu

sions opposite to those made by appellees were justified

(JA 198-199).

With respect to Psychological Problems, the court below

concluded as follows (JA 21):

3. The reasons given for disqualifying the seven

students upon the test of the Psychological Problems

obviously give consideration to race or color. On

the other hand, the rejection was not due solely to these

features. The court, however, does not rule on the

evidence to be accorded this test because the evidence

before it upon the point is too scant. . . . Therefore,

this test must be disregarded for this case.

Adaptability

The remaining appellants, who had not been disqualified

for any of the foregoing reasons (A, 7, 13, 16, 20), were

rejected by the School Board for lack of adaptability to

new situations (JA 66). The appellee Division Super

intendent of Schools defined this reason as the ability to

accept and conform to the new and different educational

environment occasioned by entering a school predominantly

occupied by pupils and teachers of another race (JA 70-72).

The sole evidence upon which the appellee School Board

acted in the application of this “ standard” was the Super

intendent’s opinion that, if these five students were ad

mitted and enrolled in the “ white” schools they sought

to enter, they would lose the position of leadership and

scholastic superiority which they enjoyed in the all-Negro

schools they attended, as well as their “ sense of belong

ing”, that this loss would be discouraging and possibly

emotionally disturbing to them (Ibid.), and that only

superior gifted Negro children could adapt to desegregated

14

schools (JA 71, 80-81). An expert witness for the appel

lants expressed a contrary view (JA 213-218).

The court below concluded that there was no ground in

the record to bar four appellants (7, 13, 16 and 20) from

the school to which they had applied for the Adaptability

reason. However, as to one appellant (A), the court

said (JA 23):

. . . In certain circumstances, undoubtedly, the line

of demarcation between it [adaptability] and racial

discrimination can he so clearly drawn, that it can be

the foundation for withholding a transfer. Pupil A

exemplifies this hypothesis.

At the conclusion of the hearing before the court below,

the court stated that it had no objection to the operation

of the schools on the basis of the assignments proposed by

appellees (i.e. to Hoffman-Boston School) pending the

court’s decision (JA 222). The 1958-1959 school term com

menced on 8 September 1958, the School Board having

once postponed the opening scheduled originally for 4

September 1958, Although the court below in its Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law, filed on 17 September

1958, disapproved appellees’ rejection of the applications

by four of the appellants for admission and enrollment in

the “ white” Stratford Junior High School, it postponed

until the commencement of the second semester of the

current school term in January 1959,3 the effective date of

its decree, entered 22 September 1958, restraining and en

joining appellees from refusing to admit, enroll and educate

these four appellants in said school (JA 11-12, 224-225)

III. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Following the decision of the Supreme Court in Brown

v. Board of Education the official, declared and operative

policy and practice of the government of the Common

wealth of Virginia became and continue to be “ massive

resistance” to desegregation. The first official action in

furtherance of this policy and practice was the Governor’s

3 The second sem ester is scheduled to commence on 2 F eb ru ary 1959.

15

appointment of the Gray Commission on Public Education,

to study and make recommendations concerning public

school desegregation. That Commission’s report was sub

mitted in November 1955. The nature of that report and

the subsequent history of “ massive resistance” is exhaus

tively treated in NAACP v. Patty, 159 F. Supp, 503, 511-

518 (E. D. Va. 1958). See also Adkins v. School Board of

the City of Newport News, 148 F. Supp. 430, 434-442

(E.D. Ya. 1957), aff’d. 246 F. 2d 325. (4th Cir. 1947).

Pursuant to the “ massive resistance” policy, the

legislature of the Commonwealth of Virginia, acting upon

recommendations by the Governor, has enacted twenty-odd

statutes designed and intended to thwart desegregation,

including provisions—already invoked—for the closing of

schools desegregated by court order, cutting-off funds for

such schools, and creating the Pupil Placement Board. See

Adkins v. School Board of the City of Newport News, and

NAACP v. Patty, supra.

The “ massive resistance” policy has had a direct bear

ing and impact upon Arlington County, Virginia and

appellees, as is indicated by the following excerpts from

the Southern School News:

Item 1—Southern School News, Vol. 2, No. 8, Feb. 1956,

p. 14:

The Arlington County School Board has adopted a

plan to integrate county schools . . .

# * ^ #

The plan presented by Supt, T. Edward Butter,

and unanimously approved by the Board, based on

the assumption that the Gray Commission proposals

will become law. The Gray plan is designed to prevent

enforced integration but not to prevent a locality from

integrating if it chooses to do so.

# # # *

Here is the text of the statement adopted by the Arling

ton Board:

“ The Arlington School Board interprets the Gray

Commission recommendation and the vote Monday,

Jan. 9, 1956, for the Constitutional Convention in Vir

ginia, to mean that no child in Virginia shall be forced

16

to attend a school in which children of both white and

Negro races are enrolled. The Arlington public

schools as a division of the public school system of

Virginia will comply with any action taken by the

State Legislature.

The Arlington School Board also believes that legis

lation will be enacted to carry out the proposed Gray

Plan and that in order to meet the Supreme Court’s

decree for ‘deliberate speed’ desegregation, it will be

necessary to provide schools, in which children of both

races may attend classes.

_ “ Assuming that the legislature will enact the provi

sions recommended by the Gray Commission, the

Arlington School Board adopts the following policy:

“ Integration will be permitted in certain elementary

schools in the Fall of 1956.

‘‘The Arlington School Board will continue the

policy of determining elementary school attendance

areas on a geographical basis.

“ Children whose parents object to their attendance

at an integrated school will be assigned to a school

that is not integrated.

“ Parents who ask to have their children assigned

to schools outside their own school district will be

responsible for their children’s transportation to and

from school.

“ Certain Arlington junior high schools will be inte

grated in the fall of 1958; certain senior high schools

will be integrated in the fall of 1958. For these grade

levels, also, a plan will be put into effect permitting

transfer of those students whose parents object to

their attending integrated schools.

“ Any child in Arlington may attend a non-segre-

gated school if his parents so desire. The Arlington

School Board does not anticipate the necessity of pay

ing tuition grants for children to attend private

schools.”

Item 2—Southern School News, Vol. 2, No. 9, Mar. 1956

p. 14:

_ Overwhelming approval of an interposition resolu

tion and consideration of another resolution to con

tinue segregation during the 1956-57 school year high

lighted February’s deliberations of the Virginia Gen

eral Assembly.

17

The Arlington County School Board’s announced

intention of beginning desegregation next fall . . . also

touched^ off a bitter controversy in the Assembly.

The fight revolved around a bill which would take

away from Arlington its right to elect its school board

members by popular vote. Arlington is the only county

in the State in which school board members are

elected.

* * # #

By a vote of 90-5 in the House of Delegates and 36-2

in the State Senate, the General Assembly on Feb. 1

adopt a resolution “ interposing the sovereignty of

Virginia against encroachment upon the reserved

powers of this state, and appealing to sister states to

resolve a question of contested power.

̂ ̂ #

The Arlington county controversy in the Assembly

centered around a bill introduced by delegate Frank

Moncure of Stafford County (a county with 14%

Negro school enrollment) to take from Arlington its

privilege of electing its school board members.

# # # ■%.

Delegate Moncure’s bill, as introduced, would pro

vide for replacing the present board members by the

system used in most Virginia counties. Under this

system, the Circuit Judge appoints a school trustee

electoral board, which in turn appoint the school board.

A House committee, however, voted to amend the

Bill to permit appointment of the school board by the

county’s governing body, the Arlington County Board.

This is the system used in all Virginia cities and in a

few counties.

Item 3—Southern School News, Vol. 2, No. 10, April

1956, p. 13:

Meanwhile in addition to approving an interposition

resolution—the Assembly’s other action dealing with

the segregation issue included:

1) Arranging for a Constitutional Convention, sub

sequently held March 5-7, to amend the State Constitu

tion to permit the payments of public money tuition-

grants to children attending private non-sectarian

schools.

18

2) Adoption of a resolution opposing racially-mixed

competition involving public school athletes.

3) Adoption of a bill to take away from Arlington

County residents the power to elect their school board.

The Arlington Board is the only one in Virginia to

announce definite plans to begin integration next

school year.

Item 4—Southern School News, Vol. 2, No. 12, June 1956,

p. 13:

Virginia has temporarily shelved—and conceivably

may abandon—its much-publicized Gray Plan for solv

ing the School Segregation problem.

* * * *

Suits seeking to force an end to racial segregation

in the schools at the start of the fall term have now

been filed against five Virginia localities—Prince Ed

ward and Arlington Counties and the cities of Nor

folk, Newport News, and Charlottesville. All cases

are in Federal District Courts.

In this context, appellants submit and urge the Court’s

consideration of their contentions in this case.

ARGUMENT

I.

THE MANNER IN WHICH APPELLEES ACTED UPON APPEL

LANTS' APPLICATIONS FOR ADMISSION TO "WHITE"

SCHOOLS IS RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN CONTRAVEN

TION OF APPELLANTS' CONSTITUTIONAL GUARANTEED

RIGHTS TO DUE PROCESS AND EQUAL PROTECTION OF

THE LAWS.

A. In the attem pted exercise of their right to enjoy educational

opportunities provided by appellees, appellants w ere su b

jected to terms and conditions based solely upon race or

color.

The elimination of race or color as a factor in the assign

ment of pupils to the public schools of Arlington County,

Virginia was decreed by the court below in July 1956. In

September 1957 the court below made a judicial finding

that appellees were still adhering to the prior practice of

racial segregation. As late as 26 August 1958', appellees

19

made the following admissions: (1 ) that they had solicited

and referred to the State Pupil Placement Board all appli

cations from pupils seeking to enjoy the constitutional

rights decreed by the court; (2) that they had cooperated

with the Pupil Placement Board in furnishing information

and in interviewing these applicants; (3) that the Pupil

Placement Board had rejected all of these applications;

and (4) that they had made and would make no assign

ments of these applicants and would admit them only to

the [Negro] schools to which they had been assigned by

the Pupil Placement Board, unless directed otherwise by

the court. This course of action appellees ‘ ‘ felt ’ ’ was com

pliance with the order of the court. (Report and Request

for Guidance, JA 7-9)

Meanwhile, on 26 August 1958, appellants filed their

Complaint in Intervention and Motion for Further Relief,

alleging, in effect, that appellees were still adhering to

their prior practice of racial segregation. Consequently,

on 28 August 1958—five days before said complaint and

motion and appellees’ report and request for guidance

were scheduled to be heard by the court and seven days

before the scheduled commencement of the 1958-1959 school

term—appellee School Board met in closed session and,

having studied and familiarized themselves, on advice of

counsel, with summaries of information pertaining to the

30 applications of Negro pupils seeking admission to

“ white” schools, found that these 30 cases fell into certain

“ groupings” or “ problem areas”, upon the basis of which

the appellee School Board voted to reject each of appel

lants’ applications (JA 43-44).

It is vital to an understanding of this proceeding to

note that these “ problem areas”, “ groupings”, “ criteria”,

“ tests” , or “ categories”, as they are referred to, were

not a “ plan”, “ assignment regulations”, or “ formal cri

teria” adopted, promulgated and published by appellees

in the regular course and discharge of their lawful duties

and responsibilities in the operation and maintenance of

the Arlington County public schools. These “ problem

areas” were formulated and used by appellees solely as

20

reasons to explain or justify their rejection of the thirty

applications which were involved in the pending litigation.

They were first disclosed and tendered to the court at the

hearing below, not as formally adopted ‘ ‘ criteria for as

signment ’ ’ applicable to all pupils seeking admission to a

school other than that in which he had theretofore been en

rolled, but as the basis upon which appellees would refuse

to assign the thirty appellants to the schools in which they

sought admission.

Thus, as appellees appeared before the court below on

2 September 1958, racial segregation in the public schools

of Arlington County, Virginia, remained an accomplished

fact. This result is consistent with the Commonwealth

of Virginia’s declared official policy of “ massive re

sistance” to desegregation and appellees ’ prior judi

cially declared adherence to the maintenance and operation

of racially segregated schools.

The pattern of “ different” treatment afforded to the

Negro appellants is patent. The evidence in the record

discloses that, notwithstanding appellees’ alleged adoption

of “ an administrative procedure applicable to all . . . ap

plicants for transfer to a school other than the one at

tended at the end of the 1957-1958 session” (Report and

Request for Guidance, JA 7), the only pupils in the Arling

ton County public school system whose requests for trans

fer were subjected to (1 ) the preparation and submission

of data to the State Pupil Placement Board (JA 25, 32);

(2) personal interviews by representatives of appellees

and the Pupil Placement Board (Report and Request for

Guidance, JA 8) ; and (3) application of the five “ criteria”

or ‘ ‘ standards ’ ’ upon the basis of which their individual re

quests were rejected, were the thirty Negroes and two

white students seeking transfers to schools theretofore at

tended exclusively by pupils of the other race (JA 74-76).

The court below specifically rejected appellants ’ conten

tion that the very formulation and use of these “ criteria”,

as well as the other special treatment accorded appellants’

applications, was racial discrimination (JA 20). This con

clusion the court justified on the basis that there was no

21

previous necessity for the use of such tests and their use

represented a new method for assignment of pupils which

was “ not discriminatory as born of a social change.”

This argument disregards the essential realities of the

situation as disclosed by the record in this case. The dif

ferent treatment accorded to appellants was not part of a

“ plan” designed or intended to facilitate and accommodate

a ‘ ‘ social change ’ ’. On the contrary, it operated, as it was

intended, to maintain the status quo. The failure and re

fusal of the court below to discern this obvious fact recalls

the expression by Chief Justice Taft in the Child Labor

Tax Case, 259 U. S. 20, 37 (1922) :

. . . All others can see and understand this. How

can we properly shut our minds to it 1

Gf. Sparroiv v. Strong, 70 IT. S. (3 Wall.) 97, 104 (1866);

Watts v. Indiana, 338 IT. S. 49, 52 (1949); Davis v. Schnell,

81 F. Supp. 872, 881 (S.D. Ala., S. I). 1949).

The evidence in this record emphatically and indisput

ably demonstrates that the method by which appellants’

transfer requests were handled applies only in those cases

that are differentiated from all others by the factor of

race alone. The limited operation of what the court below

chose to call “ assignment regulations” and an “ assign

ment plan” is underscored by the uncontradicted testimony

of appellees’ witnesses, supra, that these ‘‘assignment

regulations” had no application to any student other than

a Negro student seeking enrollment in a previously “ all-

white” school, or a white student seeking enrollment in a

previously “ all-Negro” school (JA 74-76).

As respects those to whom applied, the “ assignment

regulations” in issue establish standards and procedures

significantly variant from those normally applicable to

other children. Ordinarily, in cases other than those in

volving ‘ ‘ racial ’ ’ transfers, assignments are accomplished

routinely, without personal interviews, school board con

sideration and action, or special procedures. And, al

though it is only in cases where children seek admission

and enrollment in a school populated by pupils of the op

22

posite race that appellees applied the special standards

or criteria here involved (JA 77-78), the conrt below con

cluded this does not prove discrimination.

It is beyond question that the “ assignment plan” under

consideration subjects all Negro applicants for nonsegre-

gated education to a searching scrutiny and a survival of

disqualifying phenomena not present in ordinary cases.

This is more than merely the inconveniences, loss of time

and trouble incidental to compliance with the special “ as

signment” procedures which were applied. It is necessary

that the Negro child satisfy requirements additional to and

different from those established for and applied in all other

cases. For the Negro child, rejections may follow from

either a lack of special abilities and qualifications, or the

presence of special circumstances. The difference in treat

ment of Negro applications under the approved “ assign

ment regulations” appears plainly from the fact that no

white child is excluded from the schools to which the Negro

appellants seek admission because his academic ability is

rated below the median of the typical class in that school,

or because he has “ psychological problems”, or because

he is not “ adaptable.”

These “ criteria,” the analyses of individual records, and

interviews4 utilized in consideration of “ racial” transfer

requests, all accumulate their weight to make exceedingly

heavier demands of the Negro applicant to a white school.

The validity of this observation is amply demonstrated by

the fact that of the thirty Negro applicants submitted to

appellees’ “ assignment regulations” , all were denied the

requested transfers. This result is not remarkable when

it is considered that the “ plan” necessarily operates in

such fashion that while the Negro child, if exceptional, may

survive application of the other criteria, he is doomed to

failure under the Adaptability standard if he is not excep

4 A tran sc rip t of the personal interview s conducted by appellees and the

S ta te P up il P lacem ent B oard appears in th e record as P la in tiffs E xhib its

1, 2, 3, 4. (T . 349). The character of these interview s is exemplified by a

question asked of each p a ren t in substan tia lly the following w ords: ‘ ‘ Are

you seeking th is tra n s fe r solely because of your so-called constitutional rights

under the M ay 17, 1954 decision.”

23

tionally gifted or superior (JA 80-81). The vice in its

operation is accentuated by the consideration that the

Negro applicant to a Negro school or the white applicant to

a white school need not be special but is admitted as a

matter of course.

In the context in which these “ problem areas” were

conveniently contrived in a hastily called night meeting

five days before the trial below, and in light of the fact that

only Negro pupils were placed in such “ groupings,” and

that the entire state is politically united in “ massive

resistance” to desegregation, any consideration of these

so called “ groupings” must be with suspicious scrutiny.

Cf. Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214 (1944).

In the light of these facts and its own previous and

present experience with appellees’ efforts to thwart the

court’s prior order by disclaiming responsibility for appel

lants’ assignments, the court’s legal justification for appel

lees’ continued successful defiance of the constitutional

mandate for non-segregated public school education makes

the following statement from the concurring opinion by the

late Mr. Justice Murphy in Steele v. Louisville <fc Nashville

R. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192, 208 (1944) peculiarly apposite

here :

The utter disregard for the dignity and the well

being of colored citizens shown by this record is so

pronounced as to demand the invocation of constitu

tional condemnation. To decide the case and to analyze

the statute solely upon the basis of legal niceties, while

remaining mute and placid as to the obvious and

oppressive deprivation of constitutional guarantees,

is to make the judicial function something less than

it should be.

B. The difference betw een the treatm ent accorded appellants and

others similarly situated, based upon race alone, invokes the

condem nation of the due process and equal protection guar

antees of the Fourteenth Amendment.

J#: The equal protection clause does not leave the state free

to unjustifiably impose upon the exercise of rights by one

group requirements not applicable to other groups. Smith

v. Cahoon, 283 U. S. 553 (1931). See also Lane v. Wilson,

24

307 U. 8. 268 (1939). Classifications violate the Constitu

tion when they unjustifiably increase the group burdens,

or depreciate the group benefits, of public education.

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950); McLaurin v. Okla

homa State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 (1950); Sipuel v. Board

of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 (1948). And it is hardly neces

sary to state that the difference in treatment^ cannot be

justified upon grounds of race, Broivn v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U. S. 483 (1954); Sweatt v. Painter, supra; Ex

parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283 (1944); Skinner v. Oklahoma,

316 U. S. 535 (1942), at 541; Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S.

536 (1927), at 541. Where, as here, such requirements are

enforced at all, they must be enforced without unequal

results among groups identically situated despite differ

ence as to race^'Here the “ special” requirements con

tained in the “ plan” under consideration are imposed only

upon Negro children seeking to enter white schools, and

white 'children seeking entry to Negro schools. The single

factor determinative of its operation in particular cases

is the difference in race between the appellants and those

already in the school. Subjection to the “ plan” thus de

pends solely on race—“ simply that and nothing more.”

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 IT. S. 60, 73 (1917).

//Neither the making of classifications based upon race,

nor different treatment (by imposition of burdens or grant

of benefits) to groups defined by racial considerations,

have any reasonable relation to any legitimate purpose of

the appellee School Board. Such discriminations by the

school board constitute deprivations of liberty without

the due process of law and denials of the equal protection

of the laws in violation of the 14th Amendment. Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 IT. S. 483 (1954); Bolling v.

Sharpe, 347 IT. S. 497 (1954), Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT. S. 1

(1958).

An unjust discrimination not expressly made by the

“ standards” adopted by appellees, but made possible by

them, is nevertheless a denial of equal protection. Tick

Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) is the classic state

ment of the rights of persons aggrieved by discriminatory

25

administration of schemes appearing innocent on the sur

face, where, at pp. 373-374, the court said:

. . . Though the law itself he fair on its face and

impartial in appearance, yet, if it is applied and

administered by public authority with an evil eye and

an unequal hand, so as practically to make unjust and

illegal discriminations between persons in similar cir

cumstances, material to their rights, the denial of

equal justice is still within the prohibition of the Con

stitution.

The fact that this different treatment may apply to

white children who seek enrollment in “ Negro” schools,

as well as to Negro applicants to “ white” schools, is en

tirely beside the point. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1,

21-22 (1948). In any event, in all of its ramifications the

“ plan” here involved applied only to Negroes.

The fact that the “ plan” may not absolutely preclude

all Negro children, and that oseaptidnally-gifted: children

may survive its operation, does not save it from constitu

tional condemnation. Indisputably, it discriminates against

the class that included the Negro appellants here by im

posing greater demands upon them than upon others. This

vice in its operation alone suffices to render it invalid. As

the Court in Lane v. Wilson, supra at 275, stated in

treating another constitutional right

The [Fifteenth Amendment] nullifies sophisticated

as well as simple-minded modes of discrimination. It

hits onerous procedural requirements which effectively

handicap exercise of the franchise by the colored race

although the abstract right to vote may remain unre

stricted as to race.

Nor is the decision to be affected by the consideration

that the discrimination resulting from the operation of the

plan may not have been intended by the defendants. “ It

is immaterial that the defendants may not have intended

to deny admission on account of race or color. The inquiry

is purely objective. The result, not the intendment, of

their acts is determinative. ’ ’ Thompson v. County School

Board of Arlington County, Mupm. Non-intentional dis-

26

crimination is nonetheless unconstitutional. Cassell v.

Texas, 339 XT. S. 282 (1950); Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400

(1942); Smith v. Texas, 311 IT. S. 128 (1940). The fact

that appellee School Board sought to achieve, by the means

employed, compliance with the previous orders of the court

below is equally impotent. However, well-intended their

efforts may be, this objective cannot be attained by a device

that denies rights created or protected by the Federal

Constitution. Buchanan v. Warley, supra, at 81. //

C. The failure of the court below to recognize and condemn the

paten t discrimination in the method by which appellees acted

upon appellants' applications is inconsistent with cases in

other a reas in which State action h as been pierced and

found to represent a stratagem or device resorted to for

purposes of preserving racial discrimination.

See Terry v. Adams, 345 IT. S. 461 (1953); Smith v. All-

wright, 321 U. >S. 649 (1944); Perry v. Cyphers, 186 F. 2d.

608 (5th Cir. 1951); Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387 (4th Cir.

1947), cert. den. 333 XL S. 875 (1948). Singularly apposite

is the following excerpt from the recent opinion of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit in

Aaron v. Cooper, F.2d (8th Cir., No. 16,094, 10 No

vember 1958):

The effect of all these cases [cited above], in their

relation to the present situation has been epitomized

by the Supreme Court in Cooper v. Aaron, 78 S. Ct.

1401, 1409, as follows: “ In short, the constitutional

rights of children not to be discriminated against in

school admission on grounds of race or color declared

by this Court in the Brown case can neither be nullified

openly or directly by state legislators or state execu

tive or judicial officers, nor nullified indirectly by them

through evasive schemes for segregation whether at

tempted ‘ingeniously or ingenuously’ ” .

D. The court's conclusion that appellees' rejection of appellants'

applications w as not based upon race or color is incon

sistent with its findings that two of the reasons for rejection

involved racial considerations.

In its examination of the five reasons or “ criteria” ten

dered by appellees in justification of the rejection of ap

pellants’ applications, the court below concluded that

27

“ 'The reasons given for disqualifying the seven stu

dents upon the test of Psychological Problems ob

viously give consideration to race or color . . . (JA

21)

and with reference to the testimony of appellee Division

Superintendent in his definition and opinion concerning the

Adaptability test, the court said:

. . . Race or color is not the basis for his opinion,

though, he owns, the necessity for his decision is oc

casioned by the removal of racial bars (JA 20)

These are express findings that race or color was involved

in at least two of the reasons given by the appellee School

Board. There is an apparent inconsistency between the

court’s opinion that “ it would be almost a mental impos

sibility for a witness to say how* much weight he gave to

any one of the several factors” (JA 113) and the rationale

by which the court itself found that two of the factors

“ obviously give considerations to race and color” , but con

cluded that the other three were ‘ ‘ valid criteria, free of

taint of race or color.” (JA 22)

It is submitted that the foregoing considerations sup

port only one credible conclusion, namely, that appellees ’

action upon appellants’ applications is designed and ad

ministered to accomplish, pursuant to the policy, practice

and custom of the Commonwealth of Virginia, perpetua

tion of racial segregation in the Arlington County public

schools, in contravention of appellants’ constitutionally

guaranteed rights to due process and equal protection of

the laws.

t

f

II.

THE COURT ERRONEOUSLY CONSIDERED APPELLEES' REJEC

TION OF APPELLANTS' APPLICATIONS FOR ADMISSION,

ENROLLMENT AND EDUCATION IN DESIGNATED "WHITE"

SCHOOLS AS "ADMINISTRATIVE DETERMINATIONS" TO BE

REVIEWED PURSUANT TO THE "SUBSTANTIAL EVIDENCE"

DOCTRINE AND, HAVING THUS LIMITED ITS SCOPE OF

INQUIRY, FAILED TO DISCHARGE ITS OBLIGATION TO

MAKE AN INDEPENDENT EVALUATION AND DETERMINA

TION OF THE FACTS DECISIVE OF APPELLANTS' CONSTI

TUTIONAL CLAIM THAT THEIR EXCLUSION FROM SAID

SCHOOLS WAS BECAUSE OF RACE OR COLOR.

As this case came on for hearing in the court below, the

only issues presented upon the pleadings filed by the par

ties were: (i) appellants’ demand for the enforcement

and implementation of the previous orders of the court re

straining and enjoining appellees from refusing to admit,

enroll and educate appellants in any public school in Ar

lington County on account of race or color; and (ii) ap

pellees ’ request for guidance, in the light of their contention

that all power and authority to assign pupils to schools in

Arlington County was vested in the Pupil Placement

Board. However, at the hearing below, appellees were al

lowed to present evidence as to the action they would take

upon appellants’ applications if the court should reject ap

pellees ’ disclaimer of authority to make pupil assignments.

Thus appellees’ witness testified that appellee School Board

met, upon advice of counnsel, five days before the hearing

below, considered appellants’ applications, and voted to re

ject all of them because they fell into five “ problem areas.”

It was during cross-examination of appellees ’ principal

witness that the court below first indicated its concept of

the scope of the inquiry in the instant proceedings, as fol

lows :

The Court: As I understand the case now, it has

been channeled and reduced to the point where the

Court is actually reviewing administrative action, and

the inquiry of the Court is not whether the Court would

have done this or that, but whether there is evidence

to support what has been done; that is, that it is

neither capricious, arbitrary or unlawful . . . (JA 82)

[Emphasis supplied]

29

Having thus indicated the limits of the scope of the judi

cial inquiry in this matter, the court below, in its Finding’s

of Fact and Conclusions of Law of 17 September 1958,

stated (JA 11) :

. . . Decision is restricted to an administrative re

view. . . .

A. Appellees' action w as not such an "adm inistrative determ ina

tion" as would justify application of the “substantial evi

dence" doctrine.

In concluding that appellees’ action upon appellants’

applications was an “ administrative determination” en

titled to conclusive respect if based upon substantial evi

dence, the court below relied upon premises which are not

supported by the record in this case. More specifically,

the court stated (JA 11) :

The case signally demonstrates the soundness and

workability of these propositions: (1) that the Federal

requirement of avoiding racial exclusiveness in the

public schools—loosely termed the requirement of inte

gration—can be fulfilled reasonably and with justice

if the guide adopted is the circumstances of each child,

individually and relatively; (2) that it may he

achieved through the pursuit of any method wherein

the regulatory body can, and does, act after a fair

hearing and upon evidence; and (3) that when a con

clusion is so reached in good faith, without influence

of race, though it be erroneous, the assignment is no

longer a concern of the United States courts.

Tested by the existing record in this case appellants

contend, and argue elsewhere in this brief, that the first

and third of the above-stated “ propositions” are not sus

tained. However, the second “ proposition” is the basis

upon which the court limited the scope of its inquiry to

an “ administrative review” and commands our immediate

attention.

To justify the court’s conclusion in this case it must

appear that appellees’ action was based upon a “ fair hear

ing” . The barest essentials of a “ fair hearing” would be

notice, an opportunity to he heard, and findings based

30

upon the evidence. The fact that appellees acted ex parte,

in closed session, without notice to appellants, or an oppor

tunity for them to he heard in their own behalf is uncon

troverted in this record. As stated in one of the leading-

cases in this area, Morgan v. United States, 304 U. S. 1,

18-19 (1938):

. . . The right to a hearing embraces not only the

right to present evidence but also a reasonable oppor

tunity to know the claims of the opposing party and

to meet them . . . Those who are brought into contest

with the Government in a quasi-judicial proceeding

aimed at the control of their activities are entitled to

be fairly advised of what the Government proposes

and to be heard upon its proposals before it issues its

final command.

No such reasonable opportunity was accorded appel

lants. [Emphasis supplied]

The fundamental rationale upon which administrative

determinations are accorded respect by the courts is the

fairness and adequacy of the procedure before the admin

istrative agency. In Southern Garment Mfrs. Ass’n. v.

Fleming, 122 P. 2d 622, 632 (D.C. Cir. 1941) the stand

ards are set forth which, applied to the record in this case,

conclusively demonstrate the court’s error:

The scope of judicial review should depend largely

upon the adequacy of the preceding process. Here the

process was fair and complete. The 'Committee and

the Administrator did work that was authorized by

Congress and they did it the way that body directed.

The Committee heard evidence and deliberated. Its

report went to the Administrator. There, the proceed

ing was upon narrow, well-defined issues; the consid

eration was detailed; the affected parties or their

representatives were present; specific wage orders re

sulted. These elements, inter alia, caused the Supreme

Court, in the Opp ease to call this proceeding judicial

in character. A court, under such circumstances,

should hesitate long before nullifying the resultant

classification.

It is submitted, therefore, that the “ administrative de

termination” here was not entitled to the conclusive effect

31

and application of the “ substantial evidence” doctrine

accorded it by the court below.

B. Moreover, appellants' claim that appellees had excluded them

from the schools to which they applied, on account of their

race or color, in violation of constitutionally guaran teed

rights, obligated the court below to m ake an independent

evaluation and determ ination of the factual issues decisive

ol appellants' claim.

Accordingly, the court below was required to make its

own independent evaluation and determination, upon all

of the available and pertinent evidence, of the decisive

factual issue; viz., whether appellees refused on account

of race or color to admit, enroll and educate appellants,

who were otherwise qualified, in the “ white” schools for

which they applied. Thus, the issue of appellants’ qualifi

cations, or lack thereof, was decisive of their claimed con

stitutional right. The court was obliged to examine the

evidence on this issue not merely to determine “ whether