Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Brief Amicus Curiae, 1971. 1f9a2fed-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/01e90ae7-da5c-46e7-b7cf-e9bbb0aaa3b1/keyes-v-school-district-no-1-denver-co-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

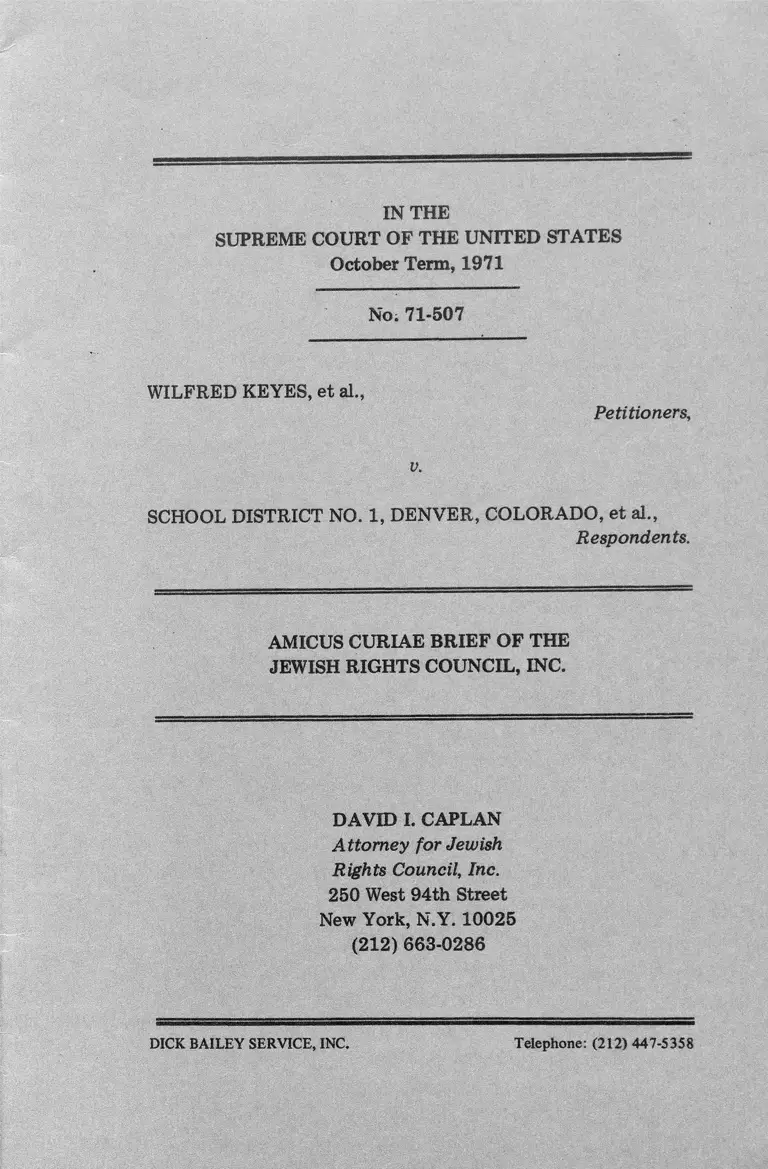

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1971

No. 71-507

WILFRED KEYES, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, DENVER, COLORADO, et al.,

Respondents.

AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF OF THE

JEWISH RIGHTS COUNCIL, INC.

DAVID I. CAPLAN

Attorney for Jewish

Rights Council, Inc.

250 West 94th Street

New York, N.Y. 10025

(212) 663-0286

DICK BAILEY SERVICE, INC. Telephone: (212) 447-5358

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Interest of the Amicus............................................................ 1

Consent to Filing.................................................................... 3

Opinions Below...................................................................... 3

Statement of the Case ............................................................ 3

ARGUMENT ........................................................................... 4

POINT I — A Federal Court Has No Power to Require a

School Board to Adopt a Plan to Achieve Ethnic Quotas of

Pupils in Neighborhood Schools ........................................... 4

Conclusion............................................................................... 10

AUTHORITIES

Page

Court’s Cases

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ...................................... 2 ,4 ,6 , 7,9

Cassel v. Texas, 3$9 U.S. 282 (1950) .............................................................................. 9

Hughes v. Superior Court o f California, 339 U.S. 460 (1950) ............................. 6, 9 ,10

Larry P. v. Riles, 41 LW 2033 (D.N. Cal, June 21,1972) .............................................. 7

Milky Way v. Leary, 305 F. Supp. 288, 292 (S.D.N.Y., 1969) ....................................5

Tinker v. Des Moines Community School District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969) ..................... 5

Other Authorities

Cahn, “Jurisprudence” , 1954 Annual Survey o f American Law ....................................7

Coleman, Equality o f Educational Opportunity (U.S.

Office of Education, 1966) ........................................................................................ 8

Glazer, “Is Bussing Necessary?” , Commentary, Vol. 53, No. 3,

p. 39, March, 1972 ................................................................................................... 6,9

N.Y. Times, March 24, 1972, p. 54, col. 1 ....................................................................... 8

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1971

No. 71-507

WILFRED KEYES, et al„

Petitioners,

v.

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, DENVER, COLORADO, et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

BRIEF OF JEWISH RIGHTS COUNCIL, INC.

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Interest of the Amicus

The Jewish Rights Council, Amicus, was founded in 1971

for the purpose of ensuring and promoting equality of all

persons before the law, and in that manner to strengthen and

1

preserve the security and constitutional rights of Jews in

America through the preservation of the rights of all Americans.

The Jewish Rights Council believes that the welfare of Jews in

the United States is inseparably related to and dependent upon

the equality of treatment of all Americans. The Jewish Rights

Council’s membership includes over one hundred Rabbis from

over a dozen States, representing Orthodox, Conservative, and

Reforiq^Congregations.

The instant case raises an important, if not crucial, issue

under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, involving the imposition by a Federal Court upon an

elected School Board of ethnic quotas of pupils in public

schools. Public education has been one of the keystones for the

unprecedented success of the Jew and other minorities in this

country, and therefore the Jewish Rights Council has a

particular interest in quality as well as equality in public

educational facilities. Being composed of members of a perse

cuted minority, the membership of the Jewish Rights Council is

especially sensitive to any and all forms of discriminations based

upon race, religion, or ethnic background. On the other hand,

the Jewish Rights Council believes that it is extremely impor

tant for the preservation of our American way of life with its

concomitant “American dream” that the rights of one group of

persons shall not be sacrificed in the name of the promotion of

another minority group. In so doing, the Jewish Rights Council

wishes to make it crystal clear that there must never be any

retreat from the principle of Brown v. Board o f Education, 347

U.S. 483 (1954), that a State should not be able to keep a

person out of a public school (or other facility) merely on the

basis of race, religion, or ethnic background.

2

Consent to Filing

This Brief is being filed with the consent of all parties to the

proceeding.

Opinions Below

The opinions of the District Court are reported at 303 F.

Supp. 279; 313 F. Supp. 61; and 313 F. Supp. 90. The opinion

of the Court of Appeals is reported at 445 F.2d 990.

Statement of the Case

This case arose when a newly elected school board rescinded

Resolutions 1520, 1524 and 1531 of the previous school board

in Denver, Colorado; and the newly elected school board

instituted Resolution 1533 instead. The rescinded Resolutions

1520, 1524 and 1531 sought to achieve a system of ethnic

quotas in the pupil compositions of various schools by means of

redistricting their respective boundaries; whereas the newly

instituted Resolution 1533 provided for a voluntary pupil

exchange program between various districts.

The plaintiffs below brought a Civil Rights action against

the school board in two causes of action which are pertinent

here:

Cause I: The rescission of Resolutions 1520, 1524, and

1531 constituted a violation of the Constitution.

Cause II: Count 1: both old and new defendant school

boards were guilty of deliberate segregation in a

“core” area of the City of Denver.

3

Count 2: The defendants had purposely maintained

inferior schools in certain designated predominantly

minority schools.

Count 3: The defendants’ neighborhood school policy

was a violation of the Constitution.

The District Court held for the plaintiffs on Cause I and on

Cause II, Count 2 only. The Court of Appeals affirmed the

judgment of the District Court, except for Cause II, Count 2 on

which the Court of Appeals reversed the judgment of the

District Court.

ARGUMENT

POINT I

A Federal Court Has No Power to Require a School

Board to Adopt a Plan to Achieve Ethnic Quotas of

Pupils in Neighborhood Schools.

The stigma of racial segregation, caused by a school board’s

refusal to allow a single person of a given ethnic or racial

background to attend a public school, is intolerable in America

under the Fourteenth Amendment. Brown v. Board o f Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). Such segregation prevents, for

example, a Black person from ever attending a certain school no

matter what ability the Black person may possess, no matter

where he lives, no matter how hard he tries. It is simply

intolerable in a society such as ours under the Fourteenth

Amendment. An entirely different question is presented where

a school board merely continues a long-standing and traditional

neutral policy of neighborhood schools in the name of public

safety, health, welfare and morals; for these objectives of a

4

society under ordered liberty axe the primary responsibility of

the States of which the school board is an agent. The State has

plenary “police power” with regard to these functions; and

there is no Federal jurisdiction which can properly operate in

this area, so long as the State and its agents remain neutral with

. regard to race, religion, and ethnic origin.

There are many legitimate “police” functions served by the

neighborhood school. With the increasing problem of groups of

students “all over the land [who] are already running loose,

conducting break-ins, sit-ins, lie-ins, and smash-ins” (Black, J.

dissenting in Tinker v. Des Moines Community School District,

393 U.S. 503 at 525; 1969), a Federal Court should be

especially careful not to undermine the primary authority of

the school board. Moreover, the neighborhood school ensures

that pupils and teachers know each other better, so that outside

untoward influences, such as drug-peddlers, are easier to detect,

isolate and eradicate. Thus, the role of the Federal judiciary

should be most sensitive to the needs of the legitimate local

“police” functions and responsibilities of school boards; and

therefore the courts should limit the scope of appropriate

judicial function and interference in the workings of the school

boards accordingly, lest the judiciary unintentionally undermine

the whole system of public education. Clearly the Federal

Courts are ill-equipped to cope with the day to day exigencies

faced by school boards.

In view of the foregoing, it seems imperative that a great

deal more than a mere preponderance of the “sharp conflict” of

evidence (445 F.2d 990, 1001) should be required before a

Federal Court intervene in the internal affairs of a school board.

See: Milky Way v. Leary, 305 F. Supp. 288, 292 (S.D.N.Y.,

1969), affd 397 U.S. 98 (1970).

5

It should be stressed repeatedly that this case emphatically

is not a case of segregation, but rather is a case involving a

finding of de facto racial “ imbalance” brought about by

housing patterns resulting from private choices. The judicial

finding below of a racial or ethnic “imbalance” necessarily

implies a finding of a departure from some arbitrarily

conjectured ethnic quota. Yet this Court itself has warned of

the tremendous difficulties and chaos which would result

from the imposition of such quotas in “a population made up

of so many diverse groups as ours? Hughes v. Superior Court

o f California, 339 U.S. 460, 464 (1950). And racial quotas

themselves may exacerbate “community tensions and

conflicts” particularly among the non-quota minorities

“through the whole gamut of racial and religious

concentrations”. Ibid.

The instant case does not at all raise a “segregation” issue as

in Brown v. Board o f Education, supra, but merely poses the

question of the appropriateness of a Federal remedy of ethnic

quotas to change ethnic pupil ratios brought about by private

housing patterns in a neighborhood school system.

The interference of the District Court below in the affairs of

the school board would not be so serious were it not for the

fact that the forgotten child in all of this is the poor black,

Hispanic, etc. or white pupil in the predominantly white school

who is “being conscripted only on the basis of income” and who

may not “escape”, as may his more affluent neighbor, either to

the suburbs or to a private school. Nathan Glazer, “Is Busing

Necessary?”, Commentary, Vol. 53 Number 3, March 1972, p.

39 at 45-46 (published by the American Jewish Committee, one

of the Amici jointly with the Anti-Defamation League in this

case). Especially is this state of affairs compounded by the fact

6

that the District Court put heavy reliance upon the relatively

low Achievement Test results of students in “designated

schools” (445 F.2d 990 at 1003). Just the other day, a

California District Court held that IQ tests were unconstitu

tionally used by a school district because they resulted in a

disproportionately large number of Black children being sent to

mentally retarded classes. Larry P. v. Riles, 41 LW 2033 (D.N.

Cal, June 21, 1972). Can constitutional rights depend upon the

latest fashions in educational testing?

Many years ago, just after the Brown, supra, decision, the

late Professor Edmond Cahn cautioned against using “expert”

sociological testimony for any purpose other than to support

legislative action or merely to reinforce common knowledge:

“It is one thing to use the current scientific findings,

however ephemeral they may be, in order to ascertain

whether the legislature has acted reasonably in adopting

some scheme of social or economic regulation; deference

here is shown not so much to the findings as to the

legislature. It would be quite another thing to have our

fundamental rights rise, fall, or change along with the

latest fashions of psychological literature. Today the social

psychologists — at least the leaders of the discipline — are

liberal and egalitarian in basic approach. Suppose, a

generation hence, some of their successors were to revert

to the ethnic mysticism of the very recent past; ... What

then would be the state of our constitutional rights?”

“Jurisprudence”, 1954 Annual Survey o f American Law,

809 at 826.

Implicit in the notion of racial quotas, to change racial

mixes brought about by private housing patterns, is the idea

that a certain mix of races in certain proportions is constitu

tionally required in order to enable the members of certain

7

minority groups to learn better in public schools. However, the

interpretation of the statistics used to validate this notion fails

to consider that there are reasons unrelated to ethnic balance

which account for the fact that a significant proportion of

Black students who attend predominantly White neighborhood

schools seem to learn better. For these Black students tend to

come from middle-class Black homes, and it may well be the

home environment which accounts for their learning better in

their neighborhood school. It is a well-established fact that

“socioeconomic factors bear a strong relation to academic

achievement” and that “schools as they have been generally run

in this country do not make much difference in the educational

achievement of students, that what is more important is the

home and community environment of children.” Equality o f

Educational Opportunity (“Coleman Report”), 1966, U.S.

Office of Education, OE 38000, at p. 21; N.Y. Times, March

24, 1972, p. 54, col. 1. Thus, purely on a socioeconomic basis,

i.e. the type of homes that Black students in neighborhood

White schools come from, it would be expected that Black

students in White neighborhood schools should achieve better

results than the poor Black students in Black neighborhood

schools, for reasons which are independent of the racial

composition of the student body in the respective schools but

which are dependent upon the type of homes the Black

students come from. Thus, it is neither invidious discrimination

nor the racial ratios in neighborhood schools which necessarily

accounts for the differences in achievement levels of Black

students in Black vs. White neighborhood schools. Moreover,

the expectations of experts regarding the educational benefits

of ethnic quotas in public schools have not been realized in

practice. N.Y. Times, ibid.

Thus, this case thrusts upon us the spectre of legally

8

mandated social experimentation. Surely the Constitution does

not require the State to perform such experiments. Particularly

is this experimentation, under the coercion of a Federal Court

order, totally unnecessary in a case where, as here, the school

board has instituted a voluntary transfer program, which can

more easily be policed by the school authorities, so that each

parent may decide for himself whether he wishes his own child

to take part in the experiment for the sake of a hoped-for better

education. There simply is no room in a case like this for any

coercion by the Court below in its judicial legislation of

school boundaries to achieve what it believes to be a proper

system of “ethnic group quotas”. Glazer, supra, 53

Commentary at 52. For the promise of Brown, supra, already

“is being realized” without such ethnic quotas. Ibid.

Ethnic quotas on Grand Juries have long ago been con

demned as unconstitutional by this Court. Cassel v. Texas, 339

U.S. 282 (1950). Likewise, this Court has held the States to be

free to ban the picketing of a business establishment for the

purpose of pressuring the hiring of employees on a racial quota

basis. Hughes v. Superior Court o f California, 339 U.S. 460

(1950). Pupil assignments on a racial basis in public schools

likewise should be avoided by school boards, and certainly not

coerced by the federal judiciary.

While the judiciary has the duty and power to implement

the negative command of the Equal Protection clause of section

1 of the Fourteenth Amendment, only the Congress is given the

authority to implement the affirmative power of section 5 of

the Fourteenth Amendment. If such a departure from tradition

al practice, as racial pupil quotas, is to become a part of our

national scheme, then at the very least it should be the Congress

which decree such a policy after appropriate hearings in depth.

9

Yet the Congress has explicitly legislated against such a policy

in enacting the Civil Rights Act, 42 USC 2000c — 6 (a)(2).

Thus, Congress has re-affirmed a policy against racial or ethnic

quotas as set forth by this Court in Hughes, supra. There is

simply no reason in law or policy why this Court should not

now likewise continue our national commitment of equality for

all, with quotas for none.

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals should be affirmed,

except insofar as the Court of Appeals affirmed the judgment of

the District Court on the First Cause of Action and in this

respect the judgment of the Court of Appeals should be

reversed; and the cause should be remanded to the District

Court with directions to dismiss the complaint.

Respectfully submitted,

David I. Caplan

250 West 94th Street

New York, N.Y. 10025

Attorney for

Jewish Rights Council, Inc.

10