Aikens v. California Respondent's Brief

Public Court Documents

September 24, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Aikens v. California Respondent's Brief, 1971. 6c5e6920-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/02171f78-5d9b-4df3-a53b-7089268e6248/aikens-v-california-respondents-brief. Accessed February 18, 2026.

Copied!

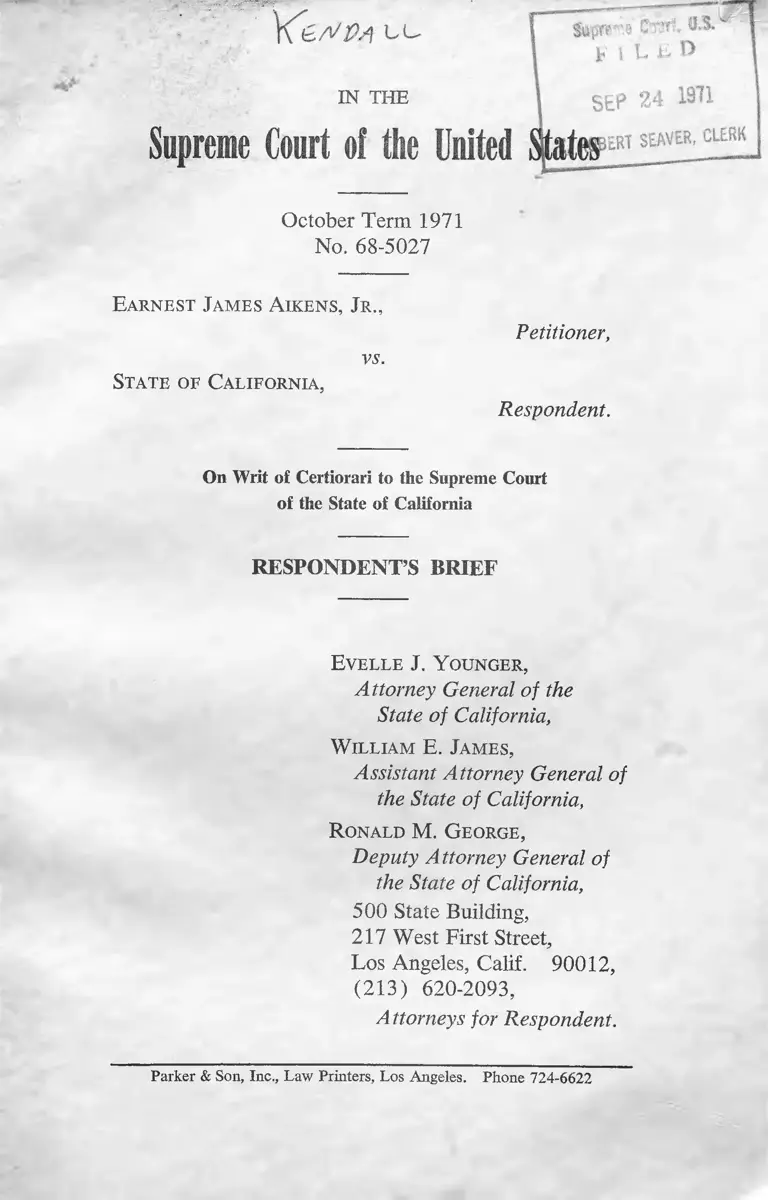

October Term 1971

No. 68-5027

Earnest James Aikens, Jr.,

vs.

State of California,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of California

RESPONDENT’S BRIEF

Evelle J. Younger,

Attorney General of the

State of California,

William E. James,

Assistant Attorney General of

the State of California,

R onald M. George,

Deputy Attorney General of

the State of California,

500 State Building,

217 West First Street,

Los Angeles, Calif. 90012,

(213) 620-2093,

Attorneys for Respondent.

Parker & Son, Inc., Law Printers, Los Angeles. Phone 724-6622

SUBJECT INDEX

Page

Question Presented ..................................................... 1

Statement of the Case ............................................... 1

A. History of the Case .................................... 1

B. Evidence Received at the Proceedings on

the Issue of Petitioner’s Guilt ................ 5

1. The Murder of Kathleen Nell Dodd .. 5

2. The Murder of Mary Winifred Eaton

.................................................................... 7

3. Statements and Conduct of Petitioner

Implicating Him in the Dodd and

Eaton Murders ..................................... 9

C. Evidence Received at the Proceedings on

the Issue of Penalty ..................................... 19

1. The Murder of Clyde J. Hardaway .. 19

2. Other Felonious Conduct by Peti

tioner: Burglaries, Attempted Rape,

and Assault With Intent to Commit

R ape........................................................ 22

3. Psychiatric and Psychological Evi

dence .................................................... 24

4. Defense Evidence Related to Peti

tioner’s Background............................... 26

5. Findings of the Trial Court in Fixing

the Punishment at D eath ...................... 29

Summary of Argument ......................................... 34

Argument ................................................................... 38

11.

Petitioner’s Sentence of Death and Pending

Execution, Resulting From His Conviction of

First Degree Murder, Do Not Comprise Cruel

and Unusual Punishment ................. ............. 38

A. Execution Is a Form of Punishment Ex

pressly Recognized by Provisions of the

Constitution and Upheld as Constitu

tional in a Long Line of Decisions by

This Court ...... ............ ............................ 38

B. Capital Punishment Is Widely Accepted

and Used in American Society and Com

ports With Contemporary “Standards of

Decency” .................................... ............. 51

C. In View of Petitioner’s Inability to Make

a Clear Showing That the Death Pen

alty Serves No Legitimate Function, the

Federal Constitution Leaves the People

of the State of California Free to De

termine Through Their Elected Repre

sentatives That the Protection of Society

Under Present Conditions Requires

Death as a Form of Punishment for

Certain Serious Offenses ...................... 71

D. The Death Penalty Is Not Arbitrarily or

Discriminatorily Imposed Upon Racial

Minorities, the Poor, or the Uneducated

in California; Prisoners Under Sentence

of Death Constitute a Representative

Cross-Section of California’s Criminal

Population ........... .................................. 103

E. Death Is Not a Cruel and Unusual Pun

ishment for Petitioner, the Unrepentant

111.

Page

Perpetrator of Three Known, Separate

Murders Committed for Pecuniary Gain

and Sexual Gratification ........................ 114

Conclusion ......................................................... ..... 117

Appendix. Defendants Under Sentence of Death

Reviewed by the California Supreme Court,

1965-1971 ............................................. App. p. 1

IV.

TABLE INDEX Page

Table A Public Opinion Polls on the Death Pen

alty: California—United States ............. ........... 56

Table B December 1970 Illinois Referendum on

Whether to Abolish the Death Penalty ............ 57

Table C Number of Prisoners Received in Prison

Under Death Sentence .......................................... 64

Table D Los Angeles Police Department Study

of the Deterrent Effect of the Death Penalty,

February, 1971 .................................................... 87

Table E Homicides in California Prisons, 1965-

1971, Committed by Adult Felons ....................... 99

Table F Race and the Imposition of the Death

Penalty in California........................ 105

Table G Race and the Commutation of Death

Sentences in California 1959-1971 ................. 108

Table H Defendants Under Sentence of Death

Reviewed by the California Supreme Court,

1965-1971 ..................... ....................._.App. p. 1

V.

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases Page

Aikens v. California, cert, granted, __ U.S. __ ,

91 S. Ct. 2280.... .......... ............ ..................... 1, 4

Coolidge v. New Hampshire, __ U.S. __ , 91

S. Ct. 2022 ____________- ............................... 71

Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459 ..... .......... -46, 50

In re Anderson, 69 Cal. 2d 613, 447 P.2d 117

(1968) ............ —- ................................. 50, 70

In re Cathey, 55 Cal. 2d 679, 361 P.2d 426

(1961) ............................. 96

In re Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436 ................39, 45, 50

In re Morse, 70 Cal. 2d 702, 452 P.2d 601

(1969) ............................................................ 100

In re Seiterle, 61 Cal. 2d 61, 394 P.2d 556

(1964), cert, denied, 379 U.S. 992 .................. 68

In re Seiterle, 71 Cal. 2d 698, 456 P.2d 129

(1969) ................................................................ 68

In re Terry, 4 Cal. 3d 911, 484 P.2d 1375

(1971) .................. .............................................. 68

Jackman v. Rosenbaum Co., 260 U.S. 22 ............ 71

Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 U.S. 262 ............................. 63

Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 F.2d 138 (8th Cir.

1968), vac’d, 398 U.S. 262 ..................— 77, 117

McGautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183 ..................

............................ 38, 42, 52, 63, 71, 75, 112, 118

McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420 .................... 101

People v. Aikens, 70 Cal. 2d 369, 450 P.2d 258

(1969) ............... ............ ........ ......................... 4

People v. Chessman, 52 Cal. 2d 467, 341 P.2d

679 (1959), cert, denied, 361 U.S. 925 ......... 70

VI.

Page

People v. Daniels, 71 Cal. 2d 1119, 459 P.2d 225

(1969) ...................................... ............. ........74, 113

People v. Daugherty, 40 Cal. 2d 876, 256 P.2d

911 (1953), cert, denied, 346 U.S. 827 ............ 50

People v. Friend, 47 Cal. 2d 749, 306 P.2d 463

(1957) ................................................................ 75

People v. Gilbert, 63 Cal. 2d 690, 408 P.2d 365

(1965), vac’d, 388 U.S. 263 .......................96, 97

People v. Goodridge, 70 Cal. 2d 824, 452 P.2d

637 (1969) ......... .....63, 67

People v. Hall, 199 Cal. 451, 249 P. 859 (1926)

..... -----........... .......... ...................... ..................... 97

People v. Jensen, 43 Cal. 2d 572, 275 P.2d 25

(1954) 96, 97

People v. Love, 56 Cal. 2d 720, 336 P.2d 33

(1961) ..................62, 80, 85, 91, 92, 93, 101, 118

People v. Morse, 60 Cal. 2d 631, 388 P.2d 33

(1964) 66, 100

People v. Morse, 70 Cal. 2d 711, 452 P.2d 607

(1969) , cert, denied, 397 U.S. 944 . 100

People v. Mutch, 4 Cal. 3d 389, 482 P.2d 633

(1971) ................................................................... 74

People v. Peete, 28 Cal. 2d 306, 169 P.2d 924

(1946), cert, denied, 329 U.S. 790 ................. 95

People v. Purvis, 52 Cal. 2d 871, 346 P.2d 22

(1959) ................................................................... 96

People v. Robinson, 61 Cal. 2d 373, 392 P.2d

970 (1964) .......................................................... 67

People v. Robles, 2 Cal. 3d 205, 466 P.2d 710

(1970) .................................................................. 96

V1X.

Page

People v. St. Martin, 1 Cal. 3d 524, 463 P.2d

390 (1970) .............................. 96

People v. Seiterle, 56 Cal. 2d 320, 363 P.2d 913

(1961) ............................ 68

People v. Seiterle, 59 Cal. 2d 703, 381 P.2d 947

(1963) , cert, denied, 375 U.S. 887 ............. 68

People v. Seiterle, 65 Cal. 2d 333, 420 P.2d 217

(1966), cert, denied, 387 U.S. 912 .................. 68

People v. Stanworth, 71 Cal. 2d 820, 457 P,2d

889 (1969) ......................... 67

People v. Terry, 57 Cal. 2d 538, 370 P.2d 985

(1962) , cert, denied, 375 U.S. 960 ............... 68

People v. Terry, 61 Cal. 2d 137, 390 P.2d 381

(1964) , cert, denied, 379 U.S. 866 ......... ........ 68

People v. Terry, 70 Cal. 2d 410, 454 P.2d 36

(1969), cert, denied, 399 U.S. 811 ............... 68

People v. Thornton, L.A. Super. Ct. No. 328445

............................................................................... 60

People v. Vaughn, 71 Cal. 2d 406, 455 P.2d 122

(1969) ................................. 96

Powell v. Texas, 392 U.S. 5 14 .... ............... ............

..............................................49, 72, 75, 93, 95, 102

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 ..............49, 51

Robinson v. United States, 324 U.S. 282 .............. 92

Rudolph v. Alabama, 375 U.S. 889 ..................... . 76

Seiterle v. Superior Court, 57 Cal. 2d 397, 369 P.

2d 697 (1962) ...................... ............................. 68

Stein v. New York, 346 U.S. 156 ......................... 113

Spencer v. Texas, 385 U.S. 554 ................... ......... 118

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 ..... 35, 40, 47, 48, 51

............................................ ......52, 54, 63, 70, 76

V lll.

Page

United States ex rel. Townsend v. Twomey, 322 F.

Supp. 158 (N.D. 111. 1971) ...... ............. ............ 68

Walz v. Tax Commission, 397 U.S. 664 ................ 71

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 __ 41, 45, 46

.................................................-................ 48, 51, 71

Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 ........................ 44, 50

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241 ..66, 75, 76, 113

Williams v. Oklahoma, 358 U.S. 576 ..... .............. 48

Winston v. United States, 172 U.S. 303 ................ 75

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 .............. 55, 66

Statutes

Act of April 30, 1790, ch. 9, §§ 1, 3, 8, 14, 33,

1 Stat. 112 .................................................... 43

Act of April 2, 1792, ch. 16, § 19, 1 Stat. 246 .... 43

Cal. Code Civ. Proc. § 170.6 ................................... 2

Cal. Mil. & Vet. Code § 1670 ........................ 73

Cal. Mil. & Vet. Code § 1672(a) ........................... 73

Cal. Pen. Code:

§ 37 ......... 73

§ 128 ............................ 73

§ 187 ............... ............. ......... ..........................2, 3

§ 188......................... ................... ........................ 3

§ 189 .......................................... 3

§ 190 ................................................................ 3, 73

§ 190.1 ................. ......................................3, 4, 103

§ 209 ......................... ............. ............ 73, 74, 95

§ 2 1 3 ..................................................................... 90

§ 2 1 9 ............................................................. 73

§ 461 ............................................................. 90

IX .

Pag©

§ 671 .......... 90

§§ 1026-27 .......................................................... 103

§ 1181(6) (7) .................. 113

§ 1193 ...................................... 4, 69

§ 1227 ........................................................ ......... 69

§ 1239 .................................... ............... .............. 67

§ 1239(b) ................................................. ......4, 113

§§ 1368-70 .................................... ............ ........... 103

§ 3046 ................ 95, 99

§ 3604 ....................................... 4

§§ 3700-06 ........................... 103

§ 4500 ..................... 73

§§ 4800-06 ........................................................ 103

§ 4801 .............................. 113

§ 4812 .................... 113

§ 12310 ....................................... 62, 73

18 U.S.C. § 1751 ......................................... .......... 62

49 U.S.C. § 1472(i) .............................................. 62

Constitutions

Cal. Const. Art. I, § 6 ...............

Cal. Const. Art. V, § 8 ............

U.S. Const. Art. I, § 9 ...............

U.S. Const. Art. II, § 2 ...............

U.S. Const. Art. Ill, § 3 .............

.............................. 44

....-........................ 95

.......................................... 39

.............................. 38

.......................................... 39

U.S. Const. Amend. V ..................................... 34, 39

U.S. Const. Amend. VIII ....34, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45

.........................46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 65, 70, 102, 117

U.S. Const. Amend. X ............................................ 39

U.S. Const. Amend. XIV ............ 40, 46, 49, 70, 118

X.

Texts Page

American Bar Association, Section of Criminal

Law Proceedings— 1959 ...................... 85

Amsterdam, Comment, Racism in Capital Punish

ment: Impact of McGautha v. California, 1

Black L. J. 185 (1971) ....... ........... ............... 306

2 Basic Writings of St. Thomas Aquinas 712, 843

(Pegis ed. 1945) ...................... 54

Bedau, Death Sentences in New Jersey 1907-1960,

19 Rutgers L. Rev. 1 (1964) ............. ...106, 107

Bedau, The Death Penalty in America 6, 20,

123, 130, 154 (rev. ed. 1967) ..........39, 58, 80, 94

Black’s Law Dictionary 1466 (4th ed. 1951) ..... 39

4 Blackstone, Commentaries 18 (Tucker ed. 1803)

........... 91

California Assembly, Report of the Select Com

mittee on the Administration of Justice, Parole

Board Reform in California 13 (1970) .............. 98

California Bureau of Criminal Statistics, Crime

and Delinquency in California— 1969 (1970) .. 105

California Bureau of Criminal Statistics, Death in

Custody—California 1962-1968 (1969) ........... 114

California Department of Corrections, California

Prisoners— 1970 (197..) ................................... 105

California Department of Corrections, California

Prisoners— 1968 (1969) ...............................64, 111

California Department of Corrections, Executions

in California 1943 Through 1963 (1965) ....79, 94

..............................................96, 109, 111, 112, 114

California Legislature, Final Calendar of Legisla

tive Business: Regular Session 1970, Assembly

Final History (Bill 20) 52 ........... 62

XI.

Page

California Legislature, Legislative Index (August

17 ,1971)................................. .......................... 62

California Legislature, Senate Weekly History

(September 9, 1971) .................. ....................... 62

California Senate, Hearing Report and Testimony

on Senate Bill No. 1, 1960 Second Extraordi

nary Session, Which Proposed to Abolish the

Death Penalty in California and to Substitute

Life Imprisonment Without Possibility of Parole

133-35, 149-54, 156, 161 (March 9, 1960) ..92, 96

Coakley, Capital Punishment, 1 Am. Crim. L. Q.

27 (May, 1963) ........ .........................85, 110, 111

Erskine, The Polls: Capital Punishment, 34 Pub.

Op. Q. 290 (1970) .................. ................ 56, 109

Federal Bureau of Investigation, Uniform Crime

Reports—-1970, 7-8, 118, 131 (August 31,

1971) ........................................... 78, 106, 108, 117

Florida Special Commission for the Study of Abo

lition of Death Penalty in Capital Cases, Re

port 31 (1965) ................... ...........................58, 81

Goldberg & Dershowitz, Declaring the Death Pen

alty Unconstitutional, 83 Harv. L. Rev. 1773

(1970) .............................................................. 44

Granucci, “Nor Cruel and Unusual Punishments

Inflicted:” The Original Meaning, 57 Calif. L.

Rev. 839 (1969) ................... 40

Holy Bible (King James version) ........ 53

Illinois Secretary of State, Constitution of the State

of Illinois & United States 13 (1971) ..... ...... 57

Laurence, A History of Capital Punishment 1

(1932) ............... 52

Xll.

Page

Legislative Drafting Research Fund, Columbia

University, Index Digest of State Constitutions

343 (2d ed. 1959) ..... ............. ......... .............. 44

Legislative Reference Service, Library of Congress,

Constitution of the United States of America 28

(rev. ann. ed. 1964) .......................................... 38

National Commission on Reform of Federal Crim

inal Laws, 2 Working Papers 1359 (n. 47)

0970) ................................................................. 75

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on C rim inal

Laws and Procedures of the Senate Committee

on the Judiciary on S. 1760, To Abolish the

Death Penalty, 90th Cong., 2d Sess. 212

(1970) ................................................................. 74

Note, The Effectiveness of the Eighth Amendment:

An Appraisal of Cruel and Unusual Punish

ment, 36 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 846 (1961) .......... 40, 44

Packer, Comment, Making the Punishment Fit the

Crime, 77 Harv. L. Rev. 1071 (1964) ....65, 66, 75

Post—Conviction Remedies in California Death

Penalty Cases, 11 Stan. L. Rev. 94 (1958) .. 69

Powers, Crime and Punishment in Early Massa

chusetts 308 (1966)........ 42

Report of New Jersey Commission to Study Capi

tal Punishment 8, 9-10 (October, 1964) ..94, 106

- ............................................................................................................. 110, 112

Royal Commission on Capital Punishment 1949-

1953 Report, 24, 274, 335, 340 (1953) ....... 78

........................................ -............................... 85, 92

St. Augustine, City of God 27 [Book I, ch. 21]

(Mod. Library ed. 1950) ................................. 54

XIII.

Pago

Special Issue, A Study of the California Penalty

Jury in First-Degree Murder Cases, 21 Stan. L.

Rev. 1297 (1969) ........ ........... .............. '...106, 109

Schuessler, The Deterrent Influence of the Death

Penalty, 284 Annals of the Am. Acad, of Pol.

and Soc. Sci. 54 (Nov. 1952) ............................ 106

State of California, Joint Legislative Committee

for Revision of the Penal Code, The Criminal

Code §315(a)(1) (Staff Digest) 18 (1971) .. 62

United Nations, Department of Economic and So

cial Affairs, Capital Punishment 9 (1968) .. 65

U.S. Bureau of Prisons, National Prisoner Statis

tics Bulletin: Capital Punishment 1930-1968

(August, 1969) 7 (Table I), 11 (Table 3), 12

(Table 4), 30 (Table 15) ........44, 62, 64, 68

.................................................................. 74, 79, 105

Van Den Haag, On Deterrence and the Death

Penalty, 60 J. Crim. L. C. & P. S. 141 (June,

1969) ..................................... 77, 86, 101, 110, 113

Miscellaneous

Allen, Capital Punishment: A Matter of Human

and Divine Justice, The Police Chief, vol. 27

(March, 1960) 1 ...................... .....................54, 59

Allen, Capital Punishment: Your Protection and

Mine, the Police Chief, Vol. 27 (June, 1960)

2 2 ........................................... .................... -......... 59

California State Prison at San Quentin, Capital

Punishment in California 3 (August 1, 1970) .. 70

California State Prison at San Quentin, Execution

Data (September 1, 1971) ............................67, 104

Christianity Today, vol. IV, No. 1 (October 12,

1959) 7 .......... ................... ....... ........ ....... ....... 58

District Attorneys’ and County Counsels’ Associa

tion of California, Official Position on Capital

Punishment 1 (September 2, 1971) .................. 86

XIV.

Page

Field Research Corporation, The California Poll,

Release No. 635 (May 22, 1969) ...... .............. . 56

Field Research Corporation, The California Poll,

Release No. 726 (September 14, 1971) ............ 56

Gallup International Inc., Gallup Opinion Index 15

(Report No. 45, March, 1969) ......................... 56

Los Angeles Police Department, Detective Bu

reau, Administrative Analysis Section, A Study

by the Los Angeles Police Department on

Capital Punishment 3, 11 (February, 1971) ....

....................... .................. .............—.86, 87, 88, 89

Los Angeles Times:

Part I, p. 1 (Dec. 13, 1958) ............................. 96

Part I, p. 8 (Feb. 14, 1959) ...... 57

Part I, p. 1 (Aug. 10, 1963) ............................. 58

Part I, p. 21 (Nov. 16, 1966) ............ 59

Part II, p. 6 (May 26, 1967) ......... I l l

Part III, p. 8 (July 15, 1967) ............................ 58

Part I, p. 20 (Dec. 18, 1969) ........................... 58

Part I, p. 1 (Aug. 8, 1970).......... 97

Part I, p. 3 (Jan. 31, 1971) ........................... 98

Part I, pp. 1, 3 (June 23, 1971) ................59, 92

Part I, p. 15 (Aug. 12, 1971) ...................... 65

P arti, p. 1 (Aug. 22, 1971) ............................... 97

Part I, p. 3 (Aug. 25, 1971) ........................... 97

Part I, p. 1 (Sept. 14, 1971) ................. 98

Part I, p. 1 (Sept. 15, 1971) ................. ...59, 98

New York Times, p. 31 (July 23, 1971) .............. 69

Sacramento Bee (May 5, 1967) .......................... 86

The American Scholar, vol. 31, No. 2 (Spring

1962) 181-91 ____ _________ ___ ___ ______ 59

The New Leader, vol. 44 (April 3, 1961) 18 __ 59

The Tidings 9 (Feb. 13, 1959) ...................... 54, 59

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term 1971

No. 68-5027

Earnest James A ikens, Jr .,

vs.

State of California,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of California

RESPONDENT’S BRIEF

QUESTION PRESENTED

The petition for writ of certiorari was granted lim

ited to the following question:

“ ‘Does the imposition and carrying out of the

death penalty in this case constitute cruel and un

usual punishment in violation of the Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments?’ ,n

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. History of the Case

In an indictment returned by the Grand Jury of

Ventura County, State of California, on April 30, 1965,

petitioner was charged with the murder of Mary Wini-

K... U.S......, 91 S. Ct. 2280.

—-2—

fred Eaton on April 26, 1965, a violation of California

Penal Code section 187. [R., Cl. Tr. I, p. I .]2 The

same grand jury on August 13, 1965, indicted peti

tioner for a second violation of the same provision, the

murder of Kathleen Nell Dodd on April 4, 1962. [R.,

Cl. Tr. Ill, p. 1.]

In each case two attorneys were appointed to rep

resent petitioner. [R., Cl. Tr. I, pp. 4, 6; Cl. Tr. Ill,

p. 3.] On motion of defense counsel the court ordered

that $750 might be expended by said counsel for in

vestigation purposes, $350 for employment of a psy

chiatrist, and $750 for an electroencephalographer.

[R., Cl. Tr. I, pp. 6, 20; Cl. Tr. Ill, p. 19.] Petitioner’s

motions for discovery of the prosecution’s evidence were

also granted. [R., Cl. Tr. Ill, p. 19; Cl. Tr. II, p. 115.1

Petitioner pleaded not guilty to each charge, and the

two cases were consolidated for trial. [R., Cl. Tr. I,

pp. 21, 54; Cl. Tr. II, p. 8.] Petitioner then exercised

his right under California law3 to disqualify the judge

to whom the case was initially assigned for trial. [R.,

Cl. Tr. Ill, pp. 43-44.] Thereafter on three occasions

petitioner personally, both his counsel, and the prose

cuting attorney waived trial by jury. [R., Cl. Tr. I, pp.

72, 77, 96-100, 109-13; Cl. Tr. II, p. 115.]

After presentation of the evidence on the issue of

guilt and extensive arguments thereon, the court found

References are to the record in the state proceedings. Pend

ing is a motion filed by respondent, with petitioner’s acquiescence,

requesting that the Court consider this case upon the original

record and dispense with the printing of an appendix, since the

record comprises several thousand pages. The designations Cl.

Tr. I and II refer to the two volumes of clerk’s transcript in

case CR 5527 and the designation Cl. Tr. I l l to the single vol

ume of clerk’s transcript in case CR 5705.

sCal. Code Civ. Proc. § 170.6.

—3

petitioner guilty of murder4 as charged in both in

dictments and found the offenses to be in the first de

gree.5 [R., Cl. Tr. II, p. 209. |

During the course of the further proceedings which

took place on the issue of penalty,B a difference of

opinion arose between petitioner and his counsel7 as

to whether petitioner should take the stand in his own

behalf, and the trial court appointed a third attorney

for the limited purpose of advising petitioner of his

rights and the consequences of taking the stand. After

consultation with counsel, and a day’s deliberation, pe

titioner chose to abide by the advice of counsel not to

testify. [R., Cl. Tr. II, pp. 269-70.]

After presentation of the evidence on the issue of

penalty and extensive argument thereon by counsel

(and by petitioner personally, by leave of the court),

the court fixed the penalty at death on the Eaton mur

der. [R., Cl. Tr. II, pp. 274, 296.] After argument on

petitioner’s motions for new trial or for reduction of

punishment, including argument by petitioner person-

4Until its amendment in 1970 to include feticide, California

Penal Code section 187 provided: “Murder is the unlawful

killing of a human being, with malice aforethought.” Malice is

defined in California Penal Code section 188.

"Premediated and deliberate murder, as well as murder com

mitted in the perpetration of certain felonies (e . g robbery, bur

glary, or rape), is murder in the first degree. Cal. Pen. Code

§ 189.

''■First degree murder is pupishable in California in the alter

native by death or life imprisonment, at the discretion of the

trier of fact, while second degree murder is punishable by im

prisonment from five years to life. Cal. Pen. Code § 190. Cali

fornia provides for bifurcated proceedings on the issues of guilt

and penalty in capital cases. Cal. Pen. Code § 190.1,

7One of petitioner’s two appointed attorneys became ill during

the course of the penalty proceedings, which continued in his

absence at the request of petitioner’s other attorney. [R., Cl.

Tr. II, p. 244.]

4

ally, said motions were denied by the trial court. [R.,

Cl. Tr. II, p. 299.] On April 7, 1966, petitioner was

sentenced to death" on the Eaton murder and to

life imprisonment on the Dodd murder,9 the sentences

being ordered to run concurrently. [R., Cl. Tr. II, p.

300; Cl. Tr. Ill, pp. 134-35.]

Petitioner filed notice of appeal from the judgment

imposing the punishment of life imprisonment. [R.,

Cl. Tr. Ill, p. 137.] Appeal to the California Supreme

Court from a judgment imposing the death penalty is

automatic under California law.10 On February 18,

1969, the California Supreme Court, in a unanimous

opinion written by Justice Peters, affirmed the judg

ment in its entirety. People v. Aikens, 70 Cal. 2d 369

[450 P. 2d 258] (1969). On March 25, 1969, the

trial court fixed June 4, 1969, as the date for peti

tioner’s execution.11

Justice Douglas extended the time for filing a peti

tion for writ of certiorari until May 30, 1969, and on

May 23, 1969, stayed petitioner’s execution. The pe

tition was filed on May 29, 1969, and, with petitioner’s

motion for leave to proceed in forma pauperis, was

granted on June 28, 1971.12

"California Penal Code section 3604 provides: “The punish

ment of death shall be inflicted by the administration of a lethal

gas.”

California Penal Code section 190.1 provides in part: “The

death penalty shall not be imposed, however, upon any person

who was under the age of 18 years at the time of the commission

of the crime.” The record (reporter’s transcript, references to

which are cited herein as R.) indicates that petitioner’s age was

several days under 17 years at the time of the Dodd murder, and

20 years at the time of the Eaton murder. [R. 4474.]

10Cal. Pen. Code § 1239(b).

n See Cal. Pen. Code § 1193.

U.S......, 91 S. Ct. 2280.

B. Evidence Received at the Proceedings on the Issue

of Petitioner’s Guilt

1. The Murder of Kathleen Nell Dodd

In April of 1962 Kathleen Nell Dodd, a 25-year-old

Caucasian woman, lived in the City of Ventura, Cali

fornia, with her husband, Ventura County Deputy

Sheriff Robert Dodd, and their two daughters, aged

three and one. [R. 57-58, 61, 88, 2860, 2882.] Mrs.

Dodd was five months pregnant at that time. [R. 127.]

Mrs. Dodd had expressed concern over the type of

neighborhood in which she lived. Shortly before her

death, a two- to three-foot length of pipe was thrown

through her front window while her husband was away

at work, and during the week or two preceding her

death she had observed a brown Dodge or Chevrolet

parked nightly near her residence between midnight and

5:00 a.m. She always locked her doors and before

opening them always ascertained the identity of her

visitors even when their arrival was expected. She had

even told a neighbor that in the event a criminal were

to intrude into her house, she would run outside in

order to lead him away from her children. [R. 59,

2001-02, 2006, 2021-22.]

At 6:30 p.m. on April 3, 1962, Deputy Dodd left

to attend his evening college classes. [R. 62.] About

midnight Mrs. Clair McWilliams, a resident in the area,

was awakened by “a very high, shrill, prolonged scream.

It had a very unearthly sound to it.” She ran to the

driveway on the adjoining property and observed a

figure running toward the gate of the patio in a rapid

zig-zag motion. She also heard the sound of twigs crack

ling to her left. As Mrs. McWilliams approached with

her 17-year-old son, who was armed with a rifle, and

her small dog, she realized that the figure was that of

—6—

a woman, from whom a steady stream of blood was

flowing, emitting the sound of a running faucet. The

blood-covered body immediately collapsed, and the

woman, later identified as Mrs. Dodd, appeared to be

dead. [R. 24-33, 54.]

Upon his return to the Dodd residence at 1:30 a.m.

after visiting some friends, Deputy Dodd had noticed

that the back door was unlocked; the television was

on; the two little girls were asleep, but Mrs. Dodd was

absent. Wet stains which he noticed on the floor, the

coffee table, and two chairs appeared to be tea stains.

Sixty dollars from a drawer, and a knife normally in

a kitchen knife rack, were missing. After several tele

phone calls to various friends to ascertain the where

abouts of his wife, Deputy Dodd contacted the Ven

tura Police Department. [R. 62-64, 67-68, 72, 80, 83,

85.]

Police inspection of the neighborhood disclosed the

following. Marks in the driveway where Mrs. Dodd’s

body was found were indicative of a struggle. A pack

of matches and a package of Salem cigarettes (a brand

smoked by both Mrs. Dodd and petitioner) were found

in this area. A trail of blood led from them to the lo

cation of the body. Across from the driveway in a

grassy area were signs of a person’s having crawled

along the ground. [R. 92, 140, 154-55, 1321-22, 1491.]

On a railroad embankment about 600 feet from

the Dodd home, the police found the missing knife be

longing to the Dodds, a pair of panties, and Mrs. Dodd’s

eyeglasses. An indentation in the soil suggested that a

person had been sitting or lying with his head at the

top of the embankment, and further down another

indentation suggested the former presence of a kneeling

-7—

person. Other marks indicated that someone had gone

up the side of the embankment and slipped backward.

[R. 83, 86, 142-43, 148-49, 153.]

The autopsy performed on Mrs. Dodd’s remains dis

closed several knife wounds in the neck penetrating

the carotid artery, the thyroid, and the voice box, caus

ing extensive hemorrhaging. There were also pressure

mark abrasions on the neck, bruises on the arms and

legs, and knife wounds on one arm and three fingers

and in the chest, one of the lungs, the abdomen, the

liver, and the back. The autopsy verified the presence

of a 5-month-old male fetus and in the vaginal area the

presence of sperm and acid phosphatase, a chemical

substance produced by the male sexual organs. In the

opinion of the pathologist, sexual intercourse had oc

curred no longer than two to three days prior to death.

[R. 180-205, 210, 215-16, 677.] Deputy Dodd last

had sexual intercourse with his wife about nine days

prior to her death. [R. 125.] Soil deposited in the

crease between the deceased’s buttocks was similar in

type to that found on the railroad embankment. [R.

217, 616-19, 677-78.]

2. The Murder of Mary Winifred Eaton

In April of 1965 Mary Winifred Eaton, a Caucasian

woman in her sixties, lived with her husband Frank

Eaton in the City of Ventura, California, with their

adopted children, Eddie Eaton and Susan Mann, and

Susan’s husband, David Mann. [R. 1128-A, 1740-41,

1802-03, 2860.] On April 26, 1965, Mr. Eaton left

for work at 7:35 a.m. and Susan, David, and Eddie left

the house at 8:20 a.m. [R. 848, 1741.] At that time

Mrs. Eaton told Susan that she was going to wax the

floors, as she apparently began to do later in the morn-

— 8

ing. [R. 1742, 1749-50.] A commercial census taker

who had previously known Mrs. Eaton received no

answer upon knocking at the Eaton residence at 10:00

a.m. but did speak to Mrs. Eaton on a second visit that

morning between 11:00 and 11:30. No witness testi

fied to seeing her alive after that hour. [R. 771-75.]

Upon returning home about 3:40 p.m., Susan and

David were greeted by petitioner from across the street.

[R. 1742-43.] Mr. Eaton returned home about 5:00

p.m. |R. 849-50.] The Eaton family became concerned

when Mrs. Eaton did not return, and they began a

search of the house. Her automobile was in the garage,

and a door between two adjoining garages, usually kept

closed, was open. [R. 857-59.] Money was missing

from a grocery purse, and a vacuum cleaner was over

turned. [R. 852, 856-57, 1746, 1763-65.] At 6:45

p.m. Mrs. Eaton’s body, initially overlooked because it

was mostly covered with bedding, was discovered by

her husband in Eddie’s bedroom. [R. 861.]

Mrs. Eaton’s hands were bound behind her with a

belt, and another belt was tied around her neck. [R.

902-04, 1358-59.] An autopsy revealed that a knife,

apparently taken from a drawer in the Eaton residence,

had been used to stab her repeatedly; the major cause

of death was hemorrhage and shock caused by a large

wound in the neck severing the jugular vein and the

trachea and reaching the spine. Other knife wounds

were located in the back of the neck and the chest,

with five entries into the heart. A vaginal smear taken

from Mrs. Eaton disclosed the presence of sperm and

seminal fluid. [R. 1631-38, 1643-46, 1649, 1662, 1807,

1834, 1839.] Mrs. Eaton had last had sexual relations

with her husband seven days prior to her death, and

—9—

apparently he was physiologically incapable of pro

ducing sperm. [R. 867, 1596.]

Mrs. Eaton’s body had been partially covered with

bedding, and an attempt had been made by her assail

ant to remove blood from the knife prior to replacing it

in the kitchen drawer. [R. 861, 1288-89, 1839.] Two

purses were found near her body. [R. 862-63.]

3. Statements and Conduct of Petitioner Implicating Him in the

Dodd and Eaton Murders

On August 25, 1961, petitioner, a Negro, was de

livered to the Southern Reception Center of the Cali

fornia Youth Authority at Norwalk; he was transferred

to the Preston School of Industry on October 10, 1961,

and paroled on March 12, 1962. [R. 1966-67, 2850. ]

On March 27, 1962, petitioner’s mother, Mrs. Liller

Lewis, purchased a brown and tan 1953 Chevrolet from

McMonica Motors. Thereafter petitioner stopped by the

agency frequently; he was driving the vehicle. [R. 2432-

37, 2479-81.]

On April 3, 1962, petitioner asked Mike Dixon to

drive him home from the residence of a friend named

Carter. When Dixon refused, petitioner pulled a knife

on him, but Dixon viewed the incident as a joke, and

he and Thomas Chambers drove petitioner home about

11:00 p.m. Petitioner told Dixon that he had a date

with a “white woman” that evening. [R. 495-99, 508-

09, 512-13.] Three or four days earlier petitioner had

spoken to Chambers about a “white woman” and had

stated that “she had a good pussy.” [R. 238.]

Dixon saw petitioner at police headquarters on the

morning after the Dodd murder, at which time peti

tioner related that he was being held on suspicion of

- 10-

having killed Mrs. Dodd. [R. 502-03. j On the fol

lowing day, at Carter’s house, petitioner told Dixon,

“ ‘I killed the Dodd woman’ ” because “ ‘[s]he was

going to cut me loose.’ ” Asked about a scratch on his

face that had not been there the evening before, peti

tioner replied, “ ‘Nothin’ but that good lovin’.’ ” When

petitioner removed his shirt while washing an automo

bile, scratches on his back were apparent. Asked about

them, he reiterated his previous remark. [R. 503, 505-

07.]

However, on the evening after the Dodd murder

Chambers had seen petitioner at Carter’s house and

had asked him about the scratch on petitioner’s face.

Petitioner replied that Ida Spellman, a policewoman,

had slapped him (which in her testimony she denied).

[R. 240-41, 607-08. j Two or three days later petitioner

told Dixon, as well as petitioner’s parole officer, that

he had scratched his face on a nail in a garage. |R.

241, 601, 605.] When Dixon and Carter confronted

him with his inconsistent explanations concerning the

scratch, petitioner said he did not wish to discuss the

matter. About this time petitioner was present when

the Dodd murder was discussed and said he did not

want to hear about it. Petitioner had money at this

time, and four or five days after the Dodd murder he

apparently lost $75 or $80 gambling. [R. 241-43.]

Three months after the murder, Deputy Dodd saw pe

titioner at the booking office of the Ventura County

Jail. At that time Deputy Dodd was not investigating

any crime involving petitioner, nor did he interrogate

him. Petitioner initiated a conversation and asked Depu

ty Dodd if he was the deputy sheriff whose wife had

recently been killed. When Deputy Dodd replied af

firmatively, petitioner declared, “ ‘It must have been a

— 1 1 -

pretty bad guy that would do something like that.’ ”

[R. 87-89, 92.]

On July 19, 1962, petitioner was returned to the cus

tody of the Youth Authority at the Preston School of

Industry and transferred to the Southern Reception

Center on September 28, 1962. He was paroled on

December 20, 1962, only to be returned to the South

ern Reception Center on February 20, 1963, and trans

ferred to the Youth Training School at Ontario, Cali

fornia, on March 1, 1963. Paroled again on January

16, 1964, petitioner was returned to the Southern Re

ception Center on March 30, 1964, apparently on a

charge of assault and battery, and transferred to the

Youth Training School on April 20, 1964. [R. 1375,

1966-67.]

During these periods of custody he made the follow

ing incriminating statements to other inmates.

In July of 1962, Barney White met petitioner in

the Ventura County Juvenile Hall. The two of them

observed Deputy Dodd and shortly thereafter petitioner

told White that when he was burglarizing the Dodd

house, Mrs. Dodd had tried to get him to leave; he

had picked up a knife, chased her outside through a

field near the railroad tracks, and raped and killed her,

leaving the knife near the tracks. [R. 453-56.]

About the same time, petitioner pointed out Deputy

Dodd to another inmate as the deputy whose wife had

been killed, and told the inmate, Bennie Rochester, that

petitioner had killed her. Subsequently, petitioner said

he “was just kidding,” and upon encountering Roches

ter shortly before the present trial, three years later, pe

titioner told him he was “going to get” him. [R. 468-

71.]

-1 2 -

At the Preston School of Industry, petitioner ap

proached Gene Noreen, who was reading a comic book.

Petitioner was “bragging” about “raping” and “killing”

a “ ‘sheriffs wife.’ ” |R, 427-28, 434, 440. J He related

that he had gone up to her house and knocked, that

she opened the door a bit, then tried to close it; he

forced his way in and tried to rape her, but she scratched

him. He related tearing off Mrs. Dodd’s clothes, chas

ing her, and cutting her up. [R. 432, 442-44.] Petition

er had a knife, which he kept sharpened, during his

stay at the institution. [R. 433. |

Richard Carreiro knew petitioner at Preston in 1962.

Petitioner told him he had gotten into an argument

with a “white girl” and had killed her. In 1963 the

two inmates saw each other at the Youth Training

School, where petitioner repeated his statement, and

possibly said he was “going with” her; he said he

“ [s] lapped her around, she started running. He was

chasing her through back ways, caught her in the yard

and stabbed her” “a lot.” [R. 474-77, 484.]

On February 26, 1965, petitioner was paroled from

the Youth Training School. [R. 1966-67.]

During the second week of April, 1965, petitioner

showed up at the office of Inspector King, Chief of

Detectives of the Ventura Police Department, and told

him that he had information on narcotics and wanted

to work as a narcotics agent. Inspector King said he

would discuss the matter in the event petitioner pro

duced some reliable information. When petitioner ap

peared at Inspector King’s office a week later and

claimed to be broke, King gave him $2 of King’s own

money. |R. 1399-1401. | During this period another of

ficer gave $1 of his own money to petitioner when he

showed up at the station claiming he was short of

money. [R. 621-22.]

On April 13, 1965, thirteen days prior to the rape-

murder of Mrs. Eaton, the county health department

tested petitioner, found him to have gonorrhea, treated

him, and told him to return monthly for blood tests.

[R. 1939-41.]

Petitioner was an acquaintance of Eddie Eaton and

had been inside the Eaton residence on five occasions.

Mr. Eaton described him as a “rather sharp boy” who

“knows what he sees,” and who “could do almost

anything if he decided to really do it”; a person “having

lots of ability” but not always truthful. [R. 886-90,

1803-06.]

On the Saturday night preceding Mrs. Eaton’s death,

petitioner and some acquaintances went to Michael

Lawthorn’s house. When the conversation turned to

girls, petitioner remarked that he knew quite a few,

that he had been out with Caucasian girls, and “that

they were a nice piece of ass.” [R. 345-49.] On the

following evening petitioner advised Lawthorn on the

subject of “how to make girls hot.” [R. 352.] Peti

tioner also attempted to listen through the wall to a

“young couple that lived next door, . . . getting ready

to go to bed,” and proposed a scheme to take photo

graphs of persons through their windows at night and

blackmail these individuals. [R. 354-55.]

On April 26, 1965, petitioner was seen in the

general neighborhood of the Eaton residence by var

ious witnesses — at 10:30 a.m., before 11:00 a.m.,

around 11:00 a.m., and at 11:30 a.m. [R. 722-23, 763,

2376-77, 2381-82, 2396-97.] About noon, petitioner

asked Mr. and Mrs. Ira Shinavar, who lived approx-

— 14-

imately across the street from the Eatons, whether

there was any work for him to do. Petitioner was of

fered a dollar to catch a gopher under their lawn.

Petitioner replied, “ ‘Well, I just got to see about get

ting me some work,’ ” and walked across the street to

the house of Mrs. Catherine Lopez. [R. 801-05.]

Mrs. Lopez, who was not fully dressed, heard a

man say “hello,” thought it was her son-in-law, and

was surprised upon looking up to see petitioner through

the screen door. He was giggling and, when asked what

he wanted, asked if he could cut her lawn. As he

spoke to her, he jiggled the doorknob. Mrs. Lopez

declined his offer, and he walked toward the corner

house where Mrs. Eaton resided. She placed the time

of his departure shortly before 12:27 p.m., because

she placed a telephone call in order to check on the

time so she would not miss the 1:00 p.m. bus. ]R.

649-54.]

Some time prior to 1:00 p.m., petitioner returned to

the Shinavars with a cultivator and some wire to use

in catching the gopher, a task which he unsuccessfully

attempted for a few minutes. Mr. Shinavar said peti

tioner had been gone 35-40 minutes between the two

times that Mr. Shinavar had seen him. Petitioner re

lated that he had “scrounged” the cultivator and the

wire “on the corner” (the residence of the Eatons, to

whom the implement belonged) and that no one was

home. Petitioner then left the Shinavars and walked to

his home, where he was met by his parole officer,

Mr. Eugene Ansell, at 1:10 p.m. [R. 806-09, 817,

865-66, 885-86, 906-07, 1372.] That afternoon he told

Mr. Ansell, “ ‘It seems like every time things start to

go well for me something happens to mess it up.’ ”

[R. 1383.]

— 15—

Later that day petitioner persuaded a friend, Willie

Tenner, to drive him to Pasadena, in Los Angeles

County. Petitioner, who had not had enough money

for bus fare that morning, purchased some perfume,

went to buy a pair of shoes, paid $5 for gas, and pur

chased a six-pack of beer. [R. 373-74, 760-63, 925-

33, 1405.] They then proceeded to Pasadena to the

home of a girl known by petitioner and spent the eve

ning with some girls, during which petitioner bought

cigarettes and a bottle of vodka for Tenner, ciga

rettes, soft drinks, bread, and popcorn for the mother

of one of the girls, four phonograph records, and more

beer. [R. 933-39, 1024-25, 1030-31.]

Petitioner tried to slip a silver ring on the finger of

Anita Jones, but she refused it, telling him to give it

to his girl friend Corina Franklin (who was only two

days from giving birth). When she asked where he ob

tained it, he said never mind where. Petitioner showed

two rings, subsequently identified as Mrs. Eaton’s wed

ding band and engagement ring, to Margaret Knowles

and told her he planned to give them to Corina. He

told her he had purchased the rings. Petitioner visited

Corina on a date which she placed at April 26, 1965.

He stayed at her house occasionally and kept some of

his clothes there. He showed her Mrs. Eaton’s two

rings. The wedding band fit her finger, but she was un

able to remove it; the engagement ring was too

small for her to wear. When Corina asked petitioner

where he had obtained the rings, he at first ignored

the question and then said he had a job as a fry cook

in Ventura. When Gorina’s mother twice asked that

same question, petitioner did not respond but indicat

ed that he was singing at a night club and working

as a fry cook. [R. 993-96, 1101-09, 1146, 1153, 1193.]

— 16

That same evening petitioner slipped Mrs. Eaton’s

engagement ring on the finger of Belinda Pickens, tell

ing her that he hoped he had gotten the right size. He

declined to tell her where he had obtained it. [R.

1021-23, 1026-29.] Thereafter petitioner, Belinda, and

some of their friends drove into the mountains. When

they parked, they “heard something,” and petitioner

took a long knife from under the car seat. [R. 1034-

36.] Later that night petitioner and Belinda spent some

time on a blanket in a park, where she declined his of

fer of sexual relations. [R. 1038-39.]

As petitioner and Tenner drove back to Ventura

that night, petitioner said to him, “ ‘When I gets back

to Ventura, the police will probably be waiting for me

when I gets back. They will probably be settin’ on my

doorstep when I get to Ventura.’ ” [R. 947.]

Indeed, they were. As he walked up his driveway

at 6:00 a.m. on April 27, 1965, petitioner noted the

presence of police officers, who had awaited him

there since 2:30 a.m. [R. 1251-53.] Petitioner inquired,

“ ‘You guys looking for me?’ ”, and accompanied the

officers to Inspector King’s office, where he appeared

very nervous, was unable to stop pacing, and expressed

his impatience. [R. 1253-54.]

Two days later, while in custody, petitioner was in

formed by Inspector King that Mrs. Eaton’s rings had

been found and remarked, “ ‘Oh man, I’ve been had.

Them damn rings.’ ” [R. 1431.] The rings, which

Mrs. Eaton had been seen wearing the day before her

death, had wax on them, possibly the type she was

using on the floor, and a quantity of blood too small to

type. [R. 1847-48, 2407-10.] Petitioner told Inspector

King the following conflicting stories concerning Mrs.

— 17—

Eaton’s rings, which bore her initials and her hus

band’s he had had them “ ‘for so goddamn long it’s

been pitiful’ ”; he “ ‘bought them from some cat . . .

down on the corner, yesterday,’ ” and that when he ob

tained the cultivator from the Eaton residence he saw

the rings “ ‘laying on the ground and I picked them up

and stuck them in my pocket.’ ” [R. 1431-32, 1436,

1444.]

In early May petitioner told an inmate in the jail,

David Luker, that he had “killed the woman . . . but he

didn’t rape her.” [R. 1694-95, 1698.]

A cellmate of petitioner’s, Bobby Williamson, testi

fied to the following statements made to him by peti

tioner in late April or early May of 1965. Petitioner said

he knew who killed Mrs. Eaton but that it was not he;

that he had gone to her house to borrow some tools,

saw the rings inside the open door, and took them.

The only person he saw on the premises was “a boy

leaving there with bloody gloves in his pocket.” [R.

1125, 1128-A, 1129.]

With reference to Mrs. Dodd, petitioner told William

son that he had been approached by two male Negroes,

one of whom was “going with” her, and that they had

asked him “did he want some pussy.” Petitioner re

sponded affirmatively, but when informed that they

were referring to Mrs. Dodd, declined the offer be

cause he “didn’t want to get in any more trouble.”

Petitioner told Williamson that someone in a bar had

approached him to tell him that Mrs. Dodd had been

raped, killed, and “thrown out in an alley.” Nonethe

less, petitioner recounted that he might as well plead

guilty since “the district attorney’s office was going to

railroad him anyway.” [R. 1131-33.]

- 1 8 -

In June or July of 1965, petitioner showed William

son his sexual organ and said he would show it to the

doctor to demonstrate that, having gonorrhea, he could

not have raped Mrs. Eaton. Petitioner also inquired

whether Williamson thought “if he tried to act insane,

would it do him any good,” and Williamson said he

“didn’t think it would with the charge he had on him.”

[R. 1133-34.] On August 19, 1965, petitioner told

Williamson, “if they didn’t get him out of that county

jail, he was going to kill someone else.” [R. 1133.]

Near the end of October, 1965, petitioner told Lieu

tenant Urias of the Ventura Police Department that one

of his fellow inmates, Sam Waldron, had made state

ments indicating the inmate’s involvement in the Dodd

murder. Petitioner also told Urias, “ ‘Well, look, I’m a

marked man. . . . And now a story about some rings.

I’m doomed.’ ” [R. 1715, 1717, 1720-21.]

On November 8, 1965, at the jail, petitioner ap

proached Deputy Sheriff Gary Markley and inquired

when petitioner would get back his shoes. When told

that they were in evidence, petitioner became excited

and said, “ ‘Those weren’t even the shoes I was wear

ing when I—’ he then stopped himself, and his face

went blank. [R. 1821-23.] On November 24, 1965,

Deputy Sheriff Don Kent, who had custody over peti

tioner during the present trial, heard petitioner make

the following statement during the course of the testi

mony of Mrs. McWilliams, the woman who found Mrs.

Dodd’s body: “ ‘She is saying things that only I know.’ ”

While Deputy Dodd was testifying with reference to the

amount of money in the drawer at the Dodd residence,

petitioner told Deputy Kent: “ ‘He wouldn’t know that

unless someone told him.’ ” During the course of a re

cess later that day, petitioner asked Deputy Kent

— 19—

on three occasions to ask Deputy Dodd who it was

who had given him all his information. And with refer

ence to Mrs. McWilliams and her son, who had ap

proached Mrs. Dodd’s body armed with a gun and in

the company of a small dog, petitioner said, “ ‘They

were out there to kill me.’ ” [R. 1825-27.]13

C. Evidence Received at the Proceedings on the Issue

of Penalty

1. The Murder of Clyde J. Hardaway

On the morning of June 7, 1962, Edward Danner,

an employee of the Park Department of the City of

Pasadena, California, discovered a body, later identi

fied as that of Clyde J. Hardaway, a male Negro in his

forties, in a park located near Devil’s Gate Dam. [R.

3424, 3481-83, 3865.] Mr. Danner attempted to

rouse the man and, realizing that he was dead, sum

moned the police. [R. 3482, 3485.]

When the police turned the body over on its back,

the penis was exposed through the fly of the pants. [R.

3881, 3883, 3929.] There was blood around the face

and skull portions of the body. [R. 3879.] Automobile

tracks were apparent near the body as well as two

moist spots which, the officers concluded, were where

two persons had urinated on the ground. [R. 3871,

3930.] An autopsy determined the cause of death to

be hemorrhage and brain damage resulting from two

gunshot wounds, in the left temple and the rear of the

skull, with particles of burned gunpowder embedded

in the area of the wounds. The fatal weapon, which

ballistics tests showed might have been a derringer,

was determined to have been fired in each instance

13The trial court’s findings of fact on the issue of guilt ap

pear at R. 3372-3419.

— 20—

from less than four inches from the victim’s head.

There was also an abrasion on the victim’s forehead

and a contusion over one of his eyes, apparently caused

by the assailant’s dragging the body along the ground.

[R. 3498-3501, 3512-16, 3528, 3921-23, 4229, 4236.]

Laboratory analysis showed 0.15 percent alcohol in the

deceased’s blood, which would have made him a

borderline drunk driver, and indicated the presence of

blood and semen on the fly area of the boxer shorts

worn by Mr. Hardaway at the time of his death. [R.

3519, 4177.]

Petitioner was identified as Hardaway’s assailant

through circumstantial evidence and his own state

ments.

On the night of his death the deceased, a homo

sexual, had been drinking heavily and had on his per

son $100-$200. He was planning to send money to his

daughter in Texas, although it was also his habit to

carry large sums of money on his person. [R. 3575-

78.] That night a friend of his saw Hardaway talk

ing to a young male Negro in Hardaway’s automobile,

and apparently saw Hardaway hand the person some

money. [R. 3565-67.]

On the morning of June 8, 1962, the deceased’s ve

hicle was found abandoned in Oxnard (a city adjacent

to Ventura). Blood spots were observed on the out

side of the vehicle. [R. 3854, 3857-59.]

On June 7, 1962, petitioner had purchased a used

automobile in the City of Ventura, making a $107

cash down payment on the $132 vehicle. [R. 416.]

That same day he was back in Pasadena giving Corina

Franklin a ride in his new acquisition. When she asked

him where he had obtained it, he replied, “ ‘None of

— 21—

your business.’ ” [R. 3659-61.] That same day peti

tioner pulled out a gun and said he was going to shoot

a dog that had been playfully chasing them. Gorina’s

inquiry as to where petitioner had obtained the weap

on met with the same response. [R. 3661-62, 3673-

74.] The vehicle was later found abandoned on a Los

Angeles street. [R. 4091-92.]

A gun having the same appearance as the one

viewed by Corina, a derringer with white handles, had

been stolen from Mr. Roy Young in Ventura on June

6, 1962, the day before Hardaway’s body was found.

The gun, which Mr. Young kept under the head of his

bed, was taken when someone broke the window over

his bed and entered while Mr. Young was at work.

The theft took place one or two days after Mr. Young

had shown the weapon to petitioner and let him fire it.

[R. 3661, 3968-72, 3975, 4156-57.] Petitioner had

told a friend, “ ‘I got a little derringer.’ ” [R. 3896.]

Petitioner’s presence in Ventura on the day of the theft

was established. [R, 4166-68.]

On June 11, 1962, a male Negro approximating peti

tioner’s physical description, although described as

about 22 years of age, pawned Mr. Hardaway’s camera

in Pasadena, signing petitioner’s name, but never re

claimed the camera after a notification of the expira

tion of the pawn period was sent to 1950 Mentone

Street, Pasadena, the former address of petitioner’s half

sister. [R. 3944-51, 4016-18, 4173, 4590, 4823.]

In June and July of 1962, petitioner volunteered to

John Pena and Arthur Pena, in the juvenile tank of the

Ventura County Jail, that petitioner had been picked

up hitchhiking in Los Angeles by a “queer,” went into

the mountains with him, pulled out his derringer, made

— 22—

him get down on his knees, and when “the guy bent

down to blow him” shot him in the head a couple of

times, killing him, taking his wallet, and using the

money to buy an automobile. [R. 4024, 4026-27, 4029-

31.] '

Sometime in 1963 or 1964, at the correctional

Youth Training School, petitioner volunteered to an

other inmate, Richard Carreiro, that he had shot a homo

sexual “ ‘blood’ ” (fellow Negro) in the head and killed

him, that it was like “playing the part of the Deacon”

(a hired gunman, portrayed on television, who made

his victims kneel and then shot them in the forehead).

[R. 3547-49, 3557.) At this institution petitioner

showed a photograph of Mr. Hardaway’s daughter, in

scribed to Hardaway and taken from his wallet, to other

inmates in the course of their showing each other their

girl friends’ pictures. [R. 3889-90, 3893.]

2. Other Felonious Conduct by Petitioner: Burglaries, At

tempted Rape, and Assault With Intent to Commit Rape

On July 6, 1961, petitioner burglarized Scritchfield

Motors in the City of Ventura. Petitioner broke several

windows, entered the premises, and attempted to steal

an automobile. Petitioner managed to elude a pursuing

police officer who fired a shot at him. [R. 4201-04,

4243-44.]

Sometime during the summer of 1962 between 9:00

and 10:00 one evening, petitioner removed the screen

and opened a window in Louise Gunn’s house in the

City of Ventura. Mrs. Gunn took her gun, “eased out”

the back door, and observed petitioner, leveling the

gun at him. He ran away and then proceeded to walk

to his house, whistling. On the following day Mrs.

Gunn spoke to petitioner and his mother about the in-

•—23-

cident, and he “said something smart” to her. Mrs.

Gunn told them that the only reason she did not shoot

him was that she had known petitioner’s mother for

years, and that if he did it again petitioner would be

killed. [R. 4094-98.] Within two weeks the gun was

stolen from her house. [R. 4118.]

On Christmas Day of 1962, Dorothy Ann Piggee,

then 15 years of age, met petitioner in the City of

Pasadena. After spending some time with him and

some friends, she accepted his offer to “walk me home

and see that I got home safely.” On the way,

petitioner suddenly pulled her down. When she began

to scream, he put his hand over her mouth and told

her to “shut up or he would kill me.” Petitioner

then terrified her by placing a letter opener at her neck

and tore off her underpants. In the victim’s words, “he

tried to have an intercourse with me, but he couldn’t.

. . . [H]e put his finger up there, and he broke my

maidenhead,” and bloody fluid was emitted from her

sexual organ. Petitioner was unsuccessful in achieving

entry with his sexual organ. He told her, “ ‘How would

you feel, not having a girl for a year.’ ” She then ran

home, with petitioner in pursuit, and complained to her

mother, who decided to take her to the emergency

hospital. Petitioner then came up to her mother and

“told her that he had did it.” [R. 4250-54, 4261,

4264, 4281-83.] The victim was medically treated for a

tear in her hymenal ring. [R. 4123-24, 4129.]

Emory McMurray, Jr. had petitioner assist him in

his commercial rubbish collection business. He directed

petitioner to pick up some refuse from Mrs. Beverly

Metcalf, but never from Mrs. Deborah Bunnell. [R.

4316-21.] On February 4, 1964, petitioner drove a

truck to Mrs. Metcalf’s residence and picked up the

-2 4 -

trash. He asked Mrs. Metcalf how her husband was

and whether they had a dog. Then he asked to use the

bathroom. After hesitating, she gave him permission,

and while he did so he left the bathroom door open.

After returning to the trash receptacles outside, peti

tioner tried to re-enter through the back door, but it

was locked. Mrs. Metcalf then denied his request to

enter to use the telephone. [R. 4330, 4333-36, 4338-

40.]

Less than an hour later, petitioner appeared at Mrs.

Bunnell’s house and asked to use the telephone, which

she let him do. He chatted with her a few minutes,

and then she suggested it might be time for him to re

turn to work. Instead of going out the front door as

she expected him to do, he sat down on a chair in the

living room. She then repeated her suggestion, where

upon he got up, spun her around, grabbed her across

the chest, and placed a hand over her mouth, dragging

her some distance. She screamed and fought him,

liberating herself and reaching the front door, and he

finally obeyed her command to leave. Petitioner’s shirt

was filthy, and she found her face and shirt covered

with black dirt. [R. 4330, 4362-71, 4378.] Her

mouth was full of soot and dirt from petitioner’s gloves,

[R. 4380.] Mrs. Bunnel reported the incident to the

police as an assault with intent to commit rape. [R.

4296-97.]

3. Psychiatric and Psychological Evidence

Three psychiatrists and one psychologist testified at

the penalty proceedings, all having been called by the

prosecution.

On March 20, 1957, Dr. Walter Streitel, a psy

chiatrist, examined petitioner at Juvenile Hall in Ven

tura. At that time, when petitioner was 11 years of

- 2 5 -

age, he had a history of “difficulties with the law.” Dr.

Streitel “found absolutely no indication of any psychotic

manifestations”; petitioner “fitted most adequately in

the category of a sociopathic personality disturbance.”

[R. 4049-52.J Dr. Streitel noted, “we haven’t seen

much benefit from all of the efforts made to rehabili

tate this kind of a person.” [R. 4053-54.] Petitioner’s

commission of the Eaton and Hardaway murders was

“entirely consistent” with the foregoing diagnosis, and

in conjunction with the commission of the Dodd murder

led Dr. Streitel to conclude: “It is rather unlikely that

rehabilitation could be expected.” [R. 4056-63.]

On September 15, 1961, Dr. Stephen Howard made

a psychological evaluation of petitioner at the Southern

Reception Center and Clinic of the California Youth

Authority. Dr. Howard concluded that petitioner was

a person “of adult normal intelligence” with “strong

underlying anger and aggression” and therefore “po

tentially dangerous.” Dr. Howard “diagnosed him basi

cally as an inadequate personality,” finding that his

character disorder was “entrenched” and that “ ‘the

prognosis is poor’ ” for change in the future. [R. 4071-

75.]

In 1963, at the Southern Reception Center and Clinic,

Dr. Joseph Veich, a psychiatrist, examined petitioner

and developed a history of his mental background.

Dr. Veich concluded that petitioner was not a “sexual

pervert or sadist” and that petitioner had no mental

or emotional disorders. Dr. Veich did not find him to

be a sociopath. Petitioner was mentally normal and

did not give much indication of remorse. [R. 3474-78.]

In April of 1964, Dr. Veich again saw petitioner at

the same institution and found his mental condition

—26—

unchanged—mentally normal and essentially healthy.

[R. 3478-79.]

On April 27, 1965, Dr. Donald Patterson, a psy

chiatrist, examined petitioner at the Ventura Police

Station. Petitioner showed no evidence of a psychotic

reaction and was fully in contact with reality. Dr. Pat

terson’s conclusion was “that he did not present a

mental illness or psychosis, but that rather he pre

sented evidence of a long-standing personality malad

justment . . . which in my opinion qualified me to

diagnose him as presenting a sociopathic personality

disturbance.” [R. 4185-87, 4191-93.] Asked what

the prospects for rehabilitation were for a man with

petitioner’s sociopathic personality difficulties, Dr. Pat

terson concluded, on the basis of petitioner’s “long his

tory of difficulties of an overt nature,” “problems in

the home situation,” “his general attitude, which is one

of tendency to deny responsibility, . . . the marked trend

toward untruthfulness,” and petitioner’s tendency to

blame the, community for not understanding him and for

treating him unfairly, that the “prospects . . . for help

ing this individual are extremely limited.” [R. 4194-96. ]

4. Defense Evidence Related to Petitioner’s Background14

Petitioner’s mother testified in his behalf. She was

59 years of age at the time of trial, was born in

Louisiana, had little schooling, and claimed to be il

literate. She described her first marriage, at the age of

13, and a second marriage to a pastor, her move to

California in 1930, her separation from her husband,

and her move to Ventura in 1936. She had supported

, 14The defense evidence which purported to controvert pe

titioner’s guilt of the charged offenses and certain of the col

lateral offenses was inconsequential and is therefore not sum

marized by respondent.

—27—

herself and her two daughters since then by doing day

housework. [R. 4469-73.] After cohabiting with an

other man, she met a serviceman who fathered peti

tioner. However, Mrs. Lewis never married again, and

shortly after petitioners birth on April 18, 1945, she

ceased seeing petitioner’s father, who failed to con

tinue supporting her or petitioner. A year after the

birth of petitioner, his father ceased writing to Mrs.

Lewis. Petitioner never saw his father thereafter. [R.

4474-77, 4480.]

She ceased doing housework at $1 an hour when

welfare officials told her to stay home to care for

petitioner and gave her $80 a month for support. [R.

4478-79.] Because she was illiterate she could not

help petitioner with Ms school homework. [R. 4480.]

She moved to $30-a-month federal housing, by which

time her welfare had increased to $110, and she

worked to bring in additional money. [R. 4481-82.]

Petitioner had trouble with the law and for about

a year was placed in the custody of Thelma Callo

way, a half sister who lived in Pasadena. [R. 4482-84.]

Her testimony described this period in his life. [R.

4579-82.] Petitioner returned to Ventura to live with

his mother. [R. 4485-87. ] Thereafter petitioner did

“o.k.” in school and had no trouble there. He was

under the supervision of a probation officer at the

time. [R. 4488-89.] Petitioner also spent about a year

in San Diego with his other half sister at this juncture

in his life, thereafter again returning to his mother in

Ventura. [R. 4489-90.] Petitioner went to school, was

arrested, and was then committed to the Los Priestos

School. Upon his release he continued his schooling in

Ventura until he was again picked up and committed

to Preston School. [R. 4490-93.] Shortly after his re-

—28-

lease in 1962, petitioner and his mother visited in

Pasadena, where he was again committed, because of

“something about a girl.” [R. 4494-96.] Upon his re

lease and return to his mother’s house, he got a job

for a couple of weeks wiping cars on a used-car lot.

He also had occasional other work, including two or

three weeks’ work with the McMurray Trash Serv

ice. Thereafter petitioner was again committed to the

California Youth Authority. Upon his release he re

turned to his mother’s house and began to seek a job.

At that point in time petitioner was arrested on the

charge of murdering Mrs. Eaton. [R. 4498-4500.] At

no time in petitioner’s life “did any man act as a

father for him.” [R. 4501.]

On cross-examination Mrs. Lewis denied the truth

of Mrs. Gunn’s accusation that petitioner had broken

into her house. Petitioner’s mother denied knowing

whether petitioner’s step-sisters had sent him home to

Ventura because he got into difficulties and they could

not handle him. [R. 4502-03.] Mrs. Lewis also did not

know whether petitioner had been in “serious trouble”

prior to his eighth birthday. She had no recollection

of a complaint from a Mrs. Kelso that petitioner had

molested her little girl. [R. 4502-04.] Petitioner al

legedly was committed to the Youth Authority on

frequent occasions when he was innocent of any wrong

doing. [R. 4511.] Mrs. Lewis did remember that peti

tioner had once escaped from Juvenile Hall. [R.

4512.]15

Petitioner’s half-sister from Pasadena, Mrs. Callaway,

was a clerical supervisor, had a college education,

15Mrs. Lewis had also taken the stand at the proceedings on

the issue of guilt, where she likewise testified to her hard-working

schedule and cash subsidies to petitioner. [R. 2241, 2269, 2318-

20, 2224.]

—29—

and was working toward a degree in sociology. [R.

4604.]

The defense also called four officers of the Cali

fornia Youth Authority, who testified that during his

various periods of commitment petitioner appeared well-

adjusted, obedient, agreeable, and generally coopera

tive. Petitioner was an especially good athlete and con

sidered the “possibility of a future in collegiate ath

letics” since one or two colleges had made him an offer.

[R. 4605-08, 4611-12, 4643-45, 4649-52, 4659-64.]

However, during his confinement he was involved in

instigating a fight, which caused a month’s postpone

ment of his parole. [R. 4654.] And one of the Y'outh

Authority officers conceded, with respect to petitioner’s

various commitments, “I honestly don’t feel that there

was a great deal of rehabilitation done with [him].”

[R. 4675.]

5. Findings of the Trial Court in Fixing the Punishment at

Death

The Honorable Jerome H. Berenson, Judge of the

Ventura Superior Court, made the following findings

as trier of fact in fixing the punishment at the con

clusion of the proceedings on the issue of penalty:

“ [Fundamental, as I see it, is the grave responsi

bility of the Court to weigh and to ponder the

ultimate question, not only by a review of all of

the past criminal record and conduct of this de

fendant, but also from as incisive an inquiry as

possible into his background, his personal history,

and his personality. In addition, in my opinion,

it is essential that the Court should probe the pos

sibility or probability or likelihood that, when and

if such opportunity should at some time in the

-—30-

future exist, the defendant would or might repeat

and recommit crimes of extreme violence. And I

must necessarily be concerned with whether or not

there is a reasonable prospect of the rehabilitation

of this individual.

“Earnest Aikens has since the age of eleven

years of age, or thereabouts, been involved in

an almost continuous pattern of anti-social and

criminal behavior of one sort or another. He has

graduated from petty and minor nuisances and