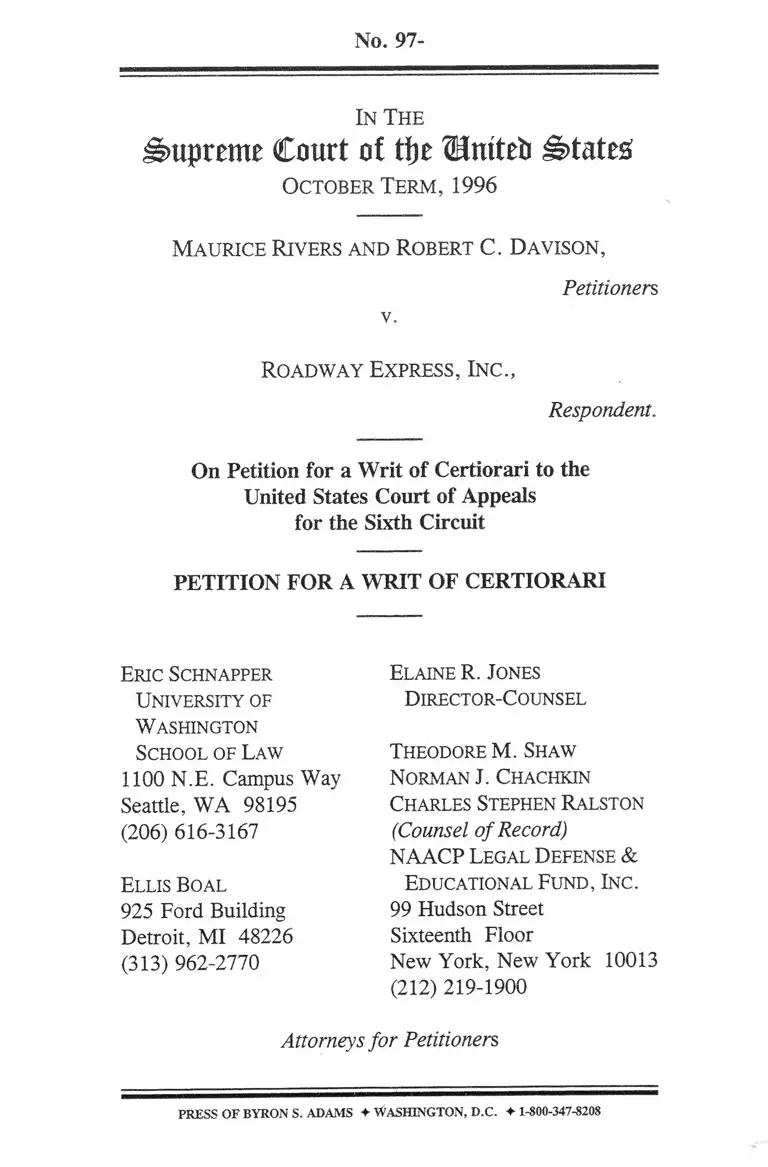

Rivers v Roadway Express Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

May 10, 1997

117 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rivers v Roadway Express Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1997. 0de8bf8c-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/02315523-d585-4c32-8fce-a96d7742db52/rivers-v-roadway-express-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 97-

In The

Supreme Court of tfje Mntteb is>tateg

October Term , 1996

Maurice Rivers and Robert C. Davison,

V.

Petitioners

Roadway Express, In c .,

Respondent.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Eric Schnapper

University of

Washington

School of Law

1100 N.E. Campus Way

Seattle, WA 98195

(206) 616-3167

Ellis Boal

925 Ford Building

Detroit, MI 48226

(313) 962-2770

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

(Counsel of Record)

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Petitioners

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS ♦ WASHINGTON, D.C. ♦ 1-800-347-8208

1

Questions Presented

1. Where a black plaintiff alleges that he was

dismissed discriminatorily in retaliation for having

successfully enforced a contractual right to grieve

disciplinary action, is he required, in order to establish a

prima facie case, or demonstrate the pretextuality of his

employer’s proffered justifications, to identify a non-

dismissed white employee whose position, situation, and

work history were "nearly identical" to his own?

2. Where a plaintiff who has successfully enforced

his contractual rights under a collective bargaining

agreement on the ground, inter alia, that he was disciplined

discriminatorily because of his race, alleges that his employer

thereafter retaliated against him because of that successful

enforcement, was it error to grant summary judgment

against the plaintiff on the ground that no specific contract

right was identified as precipitating the retaliation?

11

Parties

All of the parties are listed in the caption.

Ill

Table of Contents

Questions Presented.......................................... i

P arties.............................................................................. ii

Table of Authorities........................................................ 1

Opinions Be l o w ............................................................ 1

Jurisdiction ...................... 2

Statute Involved ................................. 2

Statement of the Case ...................................... 2

A. Proceedings Below...................

1. The Earlier Litigation. . .

2. The Current Proceedings.

3. The Ruling Below. . . . .

B. Statement of Facts. .................... 8

Reasons for Granting the Writ .................... 14

I. Certiorari Should be Granted

to Clarify the Standard for

P r o v i n g I n t e n t i o n a l

Discrimination In the Dismissal

of an Employee.................................. 14

A. The Decision Below is in

Conflict with Decisions in

Numerous Other Circuits. . . . . . 14

B. The Decision Below Is In

Conflict With Decisions of

This Court. ........................ 23

x]

U

t

o

to

IV

Conclusion

Appendix

II. Certiorari Should Be Granted

to Correct a Fundamental

Misinterpretation of the Anti-

Retaliation Protections of 42

U.S.C. § 1981 ...................... ................... 29

................................................................. 30

Table of Authorities

Cases: Pages:

Ahmed v. N.C. Servo Technology, Corp.,

1996 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 6621 (E.D. Mich. 1996) 25

Brown v. Parker-Hannifin Corp.,

746 F.2d 1407 (10th Cir. 1984)......................... 22

Bryer v. Hubert Distributors, Inc.,

1991 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 14370 (E.D. Mich. May 13,

1991) ..................................... 25

Bums v. AAF-McQuay Inc.,

96 F.3d 728 (4th Cir. 1996) . ........................ 19

Burrell v. Providence Hosp.,

104 F.3d 361, 1997 WL 729281 (6th Cir. 1996) 26

Butler v. Ohio Power Co.,

91 F.3d 143, 1996 WL 400179 (6th Cir. 1996) 26

Cassino v. Reichhold Chemicals, Inc.,

817 F.2d 1338 (9th Cir. 1987) ......................... 17

Chambers v. TRM Copy Centers Corp.,

43 F.3d 29 (2d Cir. 1994) ............................ 19

Cooper v. City of North Olmsted,

795 F.2d 1265 (6th Cir. 1986) ___ . . . . . . . . 16

Cram v. American Airlines, Inc.,

946 F.2d 423 (5th Cir. 1991) .......................... 19

Denisi v. Dominick’s Finer Foods, Inc.,

99 F.3d 860 (7th Cir. 1996) ........... ................. 17

EEOC v. Metal Service Co.,

892 F.2d 341 (3d Cir. 1990) ........................... 19

VI

Fuka v. Thomson Consumer Electronics,

82 F.3d 1397 (7th Cir. 1995) ......... .......... 18, 19

Fumco Construction Corp. v. Waters,

438 U.S. 567 (1978) ........................... .. passim

Gallo v. Prudential Services,

22 F.3d 1219 (2nd Cir. 1994) ......................... .. 25

Gerth v. Sears, Roebuck & Co.,

94 F.3d 644, 1996 WL 464984 (6th Cir. 1996) 26

Goldman v. First National Bank of Boston,

985 F.2d 1113 (1st Cir. 1993) . . . ----- . . . . . 18

Hale v. Secretary, Dept, of Treasury,

86 F.3d 1156, 1996 WL 279880 (6th Cir. 1996) . 26

Hargett v. National Westminster Bank, USA,

78 F.3d 836 (2d 1996) ................................... .. 19

Harrison v. Metro Government of Nashville,

80 F.3d 1107 (6th Cir. 1996) ...................... .. - 16

Harvis v. Roadway Express, Inc.,

923 F.2d 59 (6th Cir. 1991) . . . . . . . . . . . ----- 3

Harvis v. Roadway Express, Inc.,

973 F.2d 490 (6th Cir. 1992) ...................... 2, 4, 5

Hawkins v. The Ceco Corp,

883 F.2d 977 (11th Cir. 1989) . . . . . . . . . ----- 17

Henry v. Daytop Village,

42 F.3d 89 (2d Cir. 1994) ............................... 25

Pages

Jackson v. Ford Dealer Computer Services, Inc.,

95 F.3d 1152, 1996 WL 483028 (6th Cir. 1996) 26

Jobe v. Hardaway Management Co., Inc.,

98 F.3d 1342, 1996 WL 577638 (6th Cir. 1996) 26

Josey v. John R. Hollingsworth Corp.,

996 F.2d 632 (3d Cir. 1993) ..................... 18, 19

Kocsis v. Multi-Care Management,

97 F.3d 876 (6th Cir. 1996) ........................... 26

LaPointe v. United Autoworkers Local 600,

103 F.3d 485 (6th Cir. 1996) ........................... 25

Laughlin v. United Telephone-Southeast, Inc.,

107 F.3d 871, 1997 WL 52921 (6th Cir. 1997) 25

Lawrence v. Mars, Inc.,

955 F.2d 902 (4th Cir. 1992) ........................... 19

Lawrence v. National Westminster Bank New Jersey,

98 F.3d 61 (3d Cir. 1996) ........................... 17, 19

Leffel v. Valley Financial Services,

1997 U.S. App. LEXIS 11359 (7th Cir. 1997) 20,22

Lindsey v. Prive Corp.,

987 F.2d 324 (5th Cir. 1993) ......................... .. 19

Lytle v. Household Mfg., Inc.,

494 U.S. 545 (1990) ...................................... 5, 7

Marhtel v. Bridgestone/Firestone, Inc.,

926 F. Supp. 1293 (M.D. Tenn. 1996) ........... 25

Mayberry v. Vought Aircraft Co.,

55 F.3d 1086 (5th Cir. 1995) ....................... 19

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973) ................................... passim

Vll

Pages

vm

Pages

Mitchell v. Ball,

33 F.3d 450 (4th Cir. 1994) ............................. 19

Mitchell v. Toledo Hospital,

964 F.2d 577 (6th Cir. 1992) ..................... 16, 17

Mitchell v. White Castle Systems, Inc.,

86 F.3d 1156, 1996 WL 279863 (6th Cir. 1996) 26

Mulero-Rodriguez v. Ponte, Inc.,

98 F.2d 670 (1st Cir. 1996) ...................... .. 18

Nesbit v. Pepsico, Inc.,

994 F.2d 703 (9th Cir. 1993) ........... .......... .. . 17

Noble v. Alabama Department of Env. Mgt.,

872 F.2d 361 (11th Cir. 1989) . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

O’Connor v. Consolidated Coin Caterers Corporation,

517 U .S.__ , 134 L. Ed. 2d 433 (1996) . . . . passim

Palmer v. Health Care and Retirement, Inc., 1997 WL

135451 (6th Cir. 1997)......... .......... .. .............. 25

Palmer v. United States,

794 F.2d 534 (9th Cir. 1986) .......................... 17

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

491 U.S. 164 (1989) ................................. 3, 4, 24

Perkins v. Regents of the University of Michigan,

934 F. Supp. 857 (S.D. Mich. 1996) . . . . . . . . 25

Plair v. E.J. Brach & Sons,

105 F.3d 343 (7th Cir. 1997) ....................... 19

Quaratino v. Tiffany & Co.,

71 F.3d 58 (2d Cir. 1995) ............................... 19

IX

Reynolds v. School District No. 1 Denver, Colorado,

Pages

69 F.3d 1523 (10th Cir. 1995) ........................ 20

Rivers v. Roadway Express,

511 U.S.__ , 128 L. Ed. 2d 274 (1994) ----- 2, 5

Robinson v. Shell Oil,

519 U .S.__ , 136 L. Ed. 2d 808 (1997)........... 14

Rothmeier v. Investment Advisers, Inc.,

85 F.3d 1328 (8th Cir. 1996) ........................... 20

Rowls v. Runyon,

100 F.3d 957, 1996 WL 627712 (6th Cir. 1996) 26

Ruth v. Children’s Medical Center,

940 F.2d 662, 1991 WL 151158 (6th Cir. Aug. 8,

1991) ................................................... ............. 16

Serrano-Cruz v. DFT Puerto Rico, Inc.,

109 F.3d 23 (1st Cir. 1996) ............................... 18

Shelmon-Murchison v. Gerber Products Company,

1996 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 20735

(S.D. Mich. Sept. 13, 1996) . ............................. 25

Sinclair v. ATE Management & Service Company, Inc.,

1996 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 19921 (E.D. Mich. Nov. 27,

1996) ............. ......................................... .. • • • 25

Singh v. Shoney’s, Inc.,

64 F.3d'217 (5th Cir. 1995) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Smith v. F.W. Morse & Co., Inc.,

76 F.3d 413 (1st Cir. 1996) ............................ 18

Smith v. Stratus Computer, Inc.,

40 F.3d 11 (1st Cir. 1994) .................................. 18

X

St. Mary’s Honor Center v. Hicks,

509 U.S. 502, 125 L. Ed. 2d 407 (1993) . . . . passim

Steele v. Electronic Data Systems Corp.,

103 F.3d 131, 1996 WL 690142 (6th Cir. 1996) 26

Steward v. BASF Corporation,

1994 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 10261 (W.D. Mich. June 7,

1994) ......... .......... ..................................... .. 25

Stotts v. Memphis Fire Dept.,

858 F.2d 289 (6th Cir. 1988) ........... .. 16, 17

Suggs v. Servicemaster Education Food Management,

72 F.3d 1228 (6th Cir. 1996) .............................. 16

Sutera v. Schering Corp.,

73 F.3d 13 (2d Cir. 1995) .................................. 19

Terwilliger v. GMRI, Inc.,

952 F. Supp. 1224 (E.D. Mich. 1997) . . . . . . . 25

Texas Dept, of Community Affairs v. Burdine,

450 U.S. 248 (1981) .................................. . passim

Thomas v. Hoyt, Brumm & Link, Inc.,

910 F. Supp. 1280 (E.D. Mich. 1994) ............. 25

Timms v. Frank,

953 F.2d 281 (6th Cir. 1992) . . . . . . . ----- 16, 17

Toyee v. Janet Reno,

940 F. Supp. 1081 (E.D. Mich. 1991) . . . . . . . 25

Trujillo v. Grand Junction Regional Center,

928 F.2d 973 (10th Cir. 1991) ............. .............20

Pages

XI

United States Postal Service Board of Governors v.

Aikens,

460 U.S. 711 (1983) .................................... 23, 28

Walker v. Runyon, 99 F.3d 1140, 1996 WL 607197

(6th Cir. 1996)..................................................... 26

Wallis v. J.R. Simplot Co.,

26 F.3d 885 (9th Cir. 1994) ............................... 17

Wathen v. Lexmark Intern, Inc.,

99 F.3d 1140, 1996 WL 622955 (6th Cir. 1996) 26

Weisbrot v. Medical College of Wisconsin,

79 F.3d 677 (7th Cir. 1996) ............................. 18

Weldon v. Kraft, Inc.,

896 F.2d 793 (3d Cir. 1990) .................... 18

White v. United Autoworkers Local 600, 103 F.3d 485

(6th Cir. 1996)..................................................... 25

Wilson v. National Car Rental System, Inc.,

94 F.3d 646, 1996 WL 452882

(6th Cir. 1996) .................. 26

Wilson v. Wells Aluminum Corp.,

107 F.3d 12, 1997 WL 87218 (6th Cir. 1997) . . 25

Statutes: Pages:

Age Discrimination in Employment Act ................ .. 15

Americans with Disabilities Act ............................... 15

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981 ...........passim

Pages

X ll

Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3, 15

Labor-Management Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. § 185(a) 3

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ............. .. .................................. .. . 2

Pages

No. 97-

In The

Supreme Court ot tfte Untteb States?

October Term, 1996

Maurice Rivers and Robert C. Davison,

Petitioners,

v.

Roadway Express, Inc.,

Respondent.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari

to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Petitioners, Maurice Rivers and Robert C. Davison,

respectfully pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review the

judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

entered in this proceeding on April 10, 1997.

O pin io n s Bel o w

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit is unreported and is set out at pages la-

9a of the Appendix hereto ("App."). The Opinion and

Order of the United States Court District Court for the

Northern District of Ohio, Western Division, dated May 25,

1995, is unreported and is set out in the Appendix at pages

10a-26a. The Order of the district court denying petitioners’

motion for reconsideration, dated September 22, 1995, is

also unreported and is set out in the Appendix at pages 27a-

28a.

2

Earlier decisions in this case that are relevant to the

issues raised in the current Petition are set out in the

Appendix as follows: Memorandum and Order of the

district court dated November 30, 1988, App. at 29a-37a;

Memorandum and Order of the district court dated January

9, 1990, App. at 38a-43a; Findings of Fact and Conclusions

of Law of the district court dated October 18, 1990, App. at

44a-54a. The earlier decision of the Court of Appeals is

reported sub nom. Harvis v. Roadway Express, Inc., 973 F.2d

490 (6th Cir. 1992) and is set out in the Appendix at 55a-

70a. In addition, the prior decision of this Court is reported

at 511 U.S.__ , 128 L.Ed. 2d 274 (1994).

Ju r is d ic t io n

The decision of the Sixth circuit was entered April

10, 1997. This Court has jurisdiction to hear this case

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

St a t u t e In v o l v e d

This case involves 42 U.S.C. § 1981, which provides,

in pertinent part:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal

benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of

persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens,

and shall be subject to like punishment, pains,

penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind,

and to no other.

3

St a t e m e n t o f t h e Ca se

A. Proceedings Below.

1. The Earlier Litigation.

Maurice Rivers and Robert C. Davison, together with

a third co-plaintiff James T. Harvis, Jr.,1 filed their

Complaint against respondent, Roadway Express, Inc., their

former employer, on February 22, 1987, in the United

States District Court for the Northern district of Ohio,

Western Division, alleging that Roadway discharged them in

violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

They also asserted claims under Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq., and under § 301 of

the Labor-Management Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. § 185(a).

Petitioners also raised a hybrid §301/duty of fair

representation claim against their Union, Local Union 20,

International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs,

Warehousemen, and Helpers of America. Petitioners filed

a First Amended Complaint dated September 28, 1987.

The district court entered final judgments on all

claims of each plaintiff. Only the § 1981 claim of Rivers and

Davison that they were discriminatorily discharged in

retaliation for seeking to enforce their contractual rights is

at issue here.

The parties engaged in extensive discovery over

several months under the law as it stood prior to Patterson

v. McLean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 164 (1989). Both

Roadway and the Union moved for summary judgment. The

district court dismissed petitioners’ claims that the Union

violated its duty of fair representation, and also dismissed

petitioners’ related labor law claims against Roadway. App.

Ja rv is was a co-plaintiff, but his case was severed from that of

Rivers and Davison and tried separately. His claims are not at issue

here. See Harvis v. Roadway Express, Inc., 923 F.2d 59 (6th Cir.

1991).

4

30a-38a. The district court denied Roadway judgment,

however, on petitioners’ race discrimination claims under

Title VII and § 1981, determining that "genuine issues of

material fact exist as to plaintiffs’ claims under Section 1981

and Title VII against defendant Company." App. 37a.

Petitioners’ case was awaiting trial when this Court

handed down its decision in Patterson v. McLean Credit

Union, supra. The district court, by Order dated July 10,

1989, directed Rivers and Davison to show cause why their

§ 1981 claims should not be dismissed in light of Patterson.

Subsequently, the district court dismissed petitioners’ § 1981

claims. App. 39a-44a. Petitioners’ Title VII claims were

tried to the district court without a jury, and he found

against petitioners in all respects. App. 45a-55a.

Petitioners appealed to the Sixth Circuit solely from

the dismissal of their claims under § 1981. At issue was

whether Patterson eliminated claims that an employee had

been discharged discriminatorily for seeking to enforce his

right under an employment contract to grieve an adverse

action. However, during the pendency of the appeal,

Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1991, which

overturned Patterson in its entirety. Petitioners filed a

supplemental brief arguing that the new statute should be

applied to this action and that, therefore, all of their section

1981 claims, including the claim that their discharge was

motivated by racial discrimination, should be reinstated and

the case remanded for a jury trial.

On August 24, 1992, the court of appeals affirmed in

part and reversed in part. Hams v. Roadway Express, Inc..

973 F.2d 490 (6th Cir. 1992); App. 56a-71a. It held that

racially motivated discharge claims, as such, did not survive

Patterson. It also held that the 1991 Act should not be

applied to cases pending at the time of its enactment and

that, conversely, Patterson should be applied to cases that

arose before the date of that decision.

The court also held, however, that petitioners’ claim

5

that they had been discharged discriminatorily because they

had sought to enforce their employment contract by grieving

adverse actions against them was still covered by section

1981 after Patterson—and that, therefore, the district court

erred in dismissing that aspect of petitioners’ claims under

section 1981. The case was remanded for further

proceedings under section 1981, including a trial by jury as

guaranteed by the Seventh Amendment, citing Lytle v.

Household Mfg., Inc., 494 U.S. 545 (1990). Harvis v.

Roadway Express, 973 F.2d at 495; App. 61a-65a.

Petitioners successfully petitioned this Court for a

writ of certiorari on the issue of the application of the Civil

Rights Act of 1991 to this case. However, the Court held

that the 1991 Act did not apply, and remanded the case for

further proceedings. Rivers v. Roadway Express, Inc., 511

U.S. __ , 128 L.Ed. 2d 274 (1994). The Sixth Circuit

remanded the case to the district court for further

proceedings in conformity with its prior mandate.

2. The Current Proceedings.

On remand, no jury trial was in fact held. Rather,

respondent, Roadway Express, filed a second motion for

summary judgment in which it relied on the findings of fact

of the district court rendered after the bench trial on

petitioners’ Title VII claims, together with other citations to

pleadings and discovery developed before that trial, and the

trial transcript.

Petitioners opposed the motion, relying on matters in

the record that they claimed established that there were

disputed issues of material fact. They also reiterated their

demand for a jury trial.

The district court granted the motion for summary

judgment by applying the McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973) evidentiary analysis. The court held

that it was necessary for the petitioners to establish four

elements in order to make out a prima facie case:

6

1) plaintiff is a non-white;

2) plaintiff enforced or exercised a specific contract

right;

3) plaintiff was subject to an adverse employment

action;

4) there is a causal link between both plaintiffs

enforcement or exercise of the contract right and

plaintiffs race.

App. 18a. The court then held that petitioners had

established the first and third elements, since they are both

African Americans and they were discharged. With regard

to the second element, however, the district court held that

there was no evidence that there was a contractual right to

notice of a hearing by certified mail. It further rejected

petitioners’ argument that they were enforcing their

conceded contractual right to grieve differences with their

employer that arose out of the collective bargaining

agreement, on the ground that this claim had been raised for

the first time during the oral argument on the defendant’s

motion for summary judgment. Id., 23a.

With regard to the fourth element, the court held

that there was sufficient evidence to establish a retaliatory

motive for the adverse action since it occurred seventy-two

hours after petitioners had successfully grieved the two-day

suspension. Id., 24a-25a. However, the court further held

that the petitioners "presented] no evidence of any

comparables that could possibly raise an inference of a racial

motivation in the alleged retaliation," and that they had also

failed to present any direct evidence of a racial motivation

for the actions of the employer. Id., 25a. Therefore, the

court held, petitioners had failed to establish a prima facie

case of retaliatory contract impairment under § 1981.

The district court went on to hold that even if it were

assumed that a prima facie case had been established, the

company had come forward with evidence of a legitimate,

7

nondiscriminatory reason for their discharges, viz, "their

accumulated work records and because they disobeyed direct

orders to attend their second [post-grievance] set of

disciplinary hearings on September 26." Id., 26a. The court

said that petitioners had come forward with no evidence

which "would support a jury finding that the proffered, non

discriminatory reasons for petitioners’ discharges were a

pretext to cover defendant’s retaliatory and racial motivation

. . . ." Id., 27a. Therefore, the defendant was entitled to

judgment as a matter of law.

The district court denied the motion for

reconsideration filed by the petitioners on the grounds that

it asserted new contractual right theories and facts that were

not previously offered in opposition to the motion for

summary judgment and, therefore, it did not provide a

proper basis for reconsideration of the summary judgment

order.

3. The Ruling Below.

The petitioners appealed to the Sixth Circuit,

claiming that the grant of summary judgment denied them

their right to a jury trial under the seventh amendment and

this Court’s decision in Lytle, since there were substantial

and material matters of fact that were in dispute. The

majority of the court of appeals panel affirmed, holding,

inter alia, that the petitioners had failed to demonstrate that

comparable white employees had been treated differently

and had failed to establish that they had been denied a right

established by the collective bargaining agreement. It also

held that even if aprima facie case of discrimination through

a retaliatory discharge had been established, the respondent

had come forward with a legitimate, nondiscriminatory

reason for discharging the petitioners, viz., their

disobedience of a direct order to attend the second

disciplinary hearings and their accumulated work records.

Finally, the court of appeals held that no pretext had been

shown since a white employee had also been discharged for

refusing a direct order to attend his disciplinary' hearing.

8

App., la-6a. Judge Merritt dissented on the ground that

summary judgment should not have been granted because

the petitioners had clearly introduced evidence that they had

been retaliated against because they sought to exercise their

contractual right to grieve the earlier discharge, and that

there was ample evidence from which a jury could infer a

racially discriminatory motive in their discharge. App. 6a-

10a.

B. Statement o f Facts.

Since this case involves the grant of summaiy

judgment, the facts are set out herein in the light most

favorable to the non-moving party, the petitioners.

Roadway hired plaintiff Robert Davison to work as

a washer in its Akron facility in 1972 and hired Maurice

Rivers the following year to work as a janitor at the same

facility.2 Each worked his way up to become a mechanic.

In 1975, both were transferred to work as mechanics in

Roadway’s garage in Toledo, Ohio. For 10 years, both

worked capably in that job.3

On August 22, 1986,4 Roadway required both Rivers

and Davison to attend disciplinary hearings on their

2 R. 192: Appendix I of Plaintiff in Opposition to [First Motion

for] Summary Judgment, ("Appendix I") Davison Dep. 7/15/87, at 44-

45; Rivers Dep. 6/16/87 at 11. Citations are to the record in the court

of appeals.

3R. 192: Appendix I, Thompson Dep. 7/22/87, at 49-50.

4There were only four African-American employees working in

the Toledo garage in 1986: plaintiffs Rivers, Davison and Harvis, and

an African-American union steward, Eugene T. McCord, who had

been discharged in 1984 for refusing to have his picture taken in

circumstances an arbitrator described as showing a "callous disregard

for the personal rights of minority employees." R. 345: Second

Affidavit of Eugene T. McCord, p. 3. Mr. McCord was reinstated.

9

accumulated work record without proper notice.5

Roadway’s practice in disciplinary cases was to request a

mutually agreeable hearing date with the union for a

disciplinary hearing. The company would then notify the

employee and the union of the hearing date. The

employee’s notice would come by certified or registered

mail.6 Rivers and Davison were not given such notice,

however. Davison was simply called into the office at the

end of his shift without any prior notice, verbal or written,

that a hearing would be held that day. He protested that

he had not received proper notice.7 Rivers’ foreman

verbally informed him during the early hours of August 22

that a disciplinary hearing would be held for him later that

morning. Rivers also received no written notice.8

Because Rivers and Davison had not received proper

notice, neither of them attended the disciplinary hearings.

Roadway Express proceeded despite their absence. At the

conclusion of the hearings, Roadway suspended each

employee for two days for minor infractions, such as

"wasting time" and wearing improper shoes to work.

Both employees then filed grievances challenging

their suspensions. The grievances were heard by the Toledo

Local Joint Grievance Committee (TLJGC) on September

23, 1986.9 The TUGC was comprised of six members,

three each from union and management, including co-chairs.

5R. 192: Appendix I, Guy Dep. 8/12/87, at 151; R. 218: Complaint,

at 1 11.

6R. 345, Second McCord Affidavit, p. 2.

7R. 192: Appendix I, Davison Dep. 7/20/87, at 187-192; Guy Dep.

8/12/87, at 148.

8R. 192: Appendix I, Rivers Dep. 7/14/87, at 297-299; Guy Dep.

8/12/87, at 149.

9 R. 192: Appendix I, Rivers Dep. 7/14/87, at 316, 318.

10

Rivers and Davison were represented by Mr, McCord, who

was chief steward at the time, and by the Union business

agent, Paul Toney.10 They contended that the Company

failed to give proper notice and instead discriminatorily held

prompt hearings for these African-American employees but

not for whites.11 As Mr. McCord stated:

Between us Toney and I made three arguments.

One was that the company had rushed disciplinary

hearings on plaintiffs ahead of white employees. I

said this was discrimination and gave specific

examples.12

* * *

A second argument I made to the TUGC was that

plaintiffs had been given improper notice of their

hearings August 22. Again, no specific clause in the

contract provides for any certain type or manner of

notice of disciplinaiy hearings, but the grievance

10R. 345, Second McCord Affidavit, p. 2-3.

nR. 192: Appendix I, Rivers Dep. 7/14/87 at 321-22, 324;

McCord Dep. 9/3/87, at 285-86, 293; R. 345, Second McCord

Affidavit, p. 3.

12See also, R. 192: Appendix I, Rivers Dep. 7/14/87 at 321-22,

324; McCord Dep. 9/3/87, at 285-86, 293, explaining how they

presented examples of white employees who were not hastily brought

in for hearings as they had been, notwithstanding that Roadway’s

requests that the union agree to dates for hearings on their

disciplinary records had been pending for months. Thus, the time

between the request for hearings of the charges against Rivers and

Davison were 22 and 39 days respectively, while the time between the

request and the hearing of the eleven white employees for whom

hearings were held during 1986 and early 1987 averaged 99 days, with

only one white employee having a more prompt hearing than both

plaintiffs, and one other more prompt than Davison. R. 192:

Appendix II, Plaintiffs’ Exs. 64, 65, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77,

78, 79, 80, and 81.

11

procedure covered "any difference or dispute." That

included past practices. Notice had always been

given in the past by certified or registered mail to

employee mechanics. It was a past practice. They

had come to rely on it and they had the right to rely

on it.

* * *

Finally, Paul Toney and I both said that the

suspensions were without "just cause."13

The TUGC ruled in petitioners’ favor, determining

that "[bjased on improprieties the claim of the union is

upheld."14 The committee reversed the suspensions and

awarded petitioners-appellants back pay for the two days

they were suspended.

Roadway Labor Relations Manager James O’Neill

became enraged upon hearing of the TLGC determination,

and vowed to hold hearings on petitioners again with 72

hours. O’Neill was "hollering" and was visibly upset.15

Roadway did in fact convene disciplinary hearings on

Davison and Rivers again within three days of the

September 23, 1986, TUGC decision. Roadway also

scheduled hearings on three white employees specifically

because of Mr. McCord’s having argued that there had been

racial discrimination against Rivers and Davison because

white employees had not been called for hearings even

though their alleged offenses pre-dated those of Rivers and

Davison. Thus, Mr. O’Neill testified:

13R. 345, Second McCord Affidavit, pp. 3-4.

14R. 192: Appendix II, Plaintiffs’ Ex. 113, 114; R. 345, Second

McCord Affidavit, p. 4.

15R. 192: Appendix I, McCord Dep. 9/3/87 at 286; Rivers 7/14/87

Dep. at 327; Guy Dep. 8/12/87 at 168-69.

12

Q. And you are having these hearings [on

the charges against three white

employees] because you claim that Mr.

McCord requested them?

A. Yes.

Q. Based on his argument of race discrimination

back in September 23?

A. Yes.16

With regard to the second round of hearings,

Roadway attempted to notify petitioners of the hearings by

leaving papers at their workstations. This notice, it was

claimed, also fell short of the standard procedure of sending

the notice by certified mail, which petitioners believed was

required.17 Davison and Rivers went to the hearing room,

but objected to the lack of notice and again declined to

remain. Again the hearings were held in their absence. The

second disciplinary hearings were conducted by another

member of Roadway management, Robert Kresge, but

O’Neill also personally attended.18 As a result of the

hearings, petitioners were discharged on September 26,1986.

Petitioners each claimed that no one informed them

16R. 327: Testimony of James O’Neill, Transcript of Trial, Vol. II,

pp. 524, 531. The conclusion that white employees were included in

the disciplinary actions so that the company would be able to

discharge petitioners in retaliation for having exercised their

contractual rights was supported by the testimony of another white

employee, Mr. Russell, noted by Judge Merritt in dissent below.

Russell was also fired for violating a direct order but was reinstated.

He was told by a supervisor that he was fired so that "Roadway would

have a defense . . . that they don’t only fire black people . . ." App.

9a.

17R. 192: Appendix I, Rivers Dep. 7/14/87, at 339-40, 347, 378-9;

Toney Dep. 10/1/87, at 19-20.

18R. 192: Appendix I, O ’Neill Dep. 8/13/87, at 63, 69.

13

that failure to attend the second disciplinary hearing would

cause his discharge.19 The Company, on the other hand,

asserted that the employees’ failure to attend the hearings in

disobedience of what it characterized as a "direct order" was

the basis for its decision immediately to discharge them

(even though it had not discharged the petitioners when they

refused to attend the hearings held before their successful

grievance).

With regard to the three white employees who

received disciplinary hearings on the same day because the

union steward raised the issue of racial discrimination, one,

Mr. Sedelbauer, also refused several orders to attend his

hearing and was discharged.20 A second white employee,

Mr. Bradley, had the day of the hearing off. He was neither

on the clock nor was he ordered to attend the hearing.

Nevertheless, the hearing was held in his absence and he was

given a two-day suspension. The third white employee, Mr.

Swartzfager,21 was on the clock but obeyed the order to

attend the hearing. He was suspended for two days. App.

27a.

19See, e.g., R. 192: Appendix I, Davison Dep. 7/20/87, at 227, 232;

Davison Dep. 8/20/87.

P etitioners argued that Mr. Sedelbauer’s circumstances were

different in that he did not attend the disciplinary hearing at all,

while petitioners did but left before the hearings were concluded.

21There had been a six-month delay between the alleged

misconduct of this white employee and the scheduling of a hearing in

response to McCord’s argument at the petitioners’ initial hearings.

14

R ea so n s f o r G r a n t in g t h e W r it

This case involves a claim of discrimination more

egregious than presented in Robinson v. Shell Oil, 519 U.S.

__ 136 L.Ed. 2d 808 (1997). The petitioners allege that

they were fired from long-standing employment with

Roadway Express because they grieved, successfully,

disciplinary charges on the ground that they had been

subjected to different proceedings because of their race.

After winning their grievance, new disciplinary hearings were

set on short notice. Petitioners testified that they were not

warned that they could be terminated if they did not attend

the hearings; nevertheless, they were fired when they left.

All petitioners have sought is a jury trial on the merits of

their claims. They have been denied this right because of

the mechanical application by the courts below of rules for

establishing a prima facie case of discrimination and for

proving the ultimate fact of discrimination.

I.

Certiorari Should be Granted to Clarify the

Standard for Proving Intentional Discrimination

In the Dismissal of an Employee.

A. The Decision Below is in Conflict with Decisions in

Numerous Other Circuits.

Twenty-four years ago in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v.

Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973), this Court set out a paradigm

for establishing a prima facie case of intentional

discrimination in the hiring of employees. 411 U.S. at 802.

For at least a decade, however, by far the largest number of

civil actions filed under federal anti-discrimination statutes

have concerned dismissals rather than initial hiring decisions.

To this veiy large group of employment discrimination

actions the McDonnell Douglas formulation, which expressly

concerns "applications," cannot be applied as written. Texas

Dept, o f Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. 248, 253 n.6

(1981).

15

As a consequence, this Court noted in O’Connor v.

Consolidated Caterers Corporation, 517 U.S.__ , 134L.Ed.2d

433, 438 (1996), the circuit courts in age discrimination cases

have "applied some variant of the basic evidentiary

framework set forth in McDonnell Douglas." 134 L.Ed.2d at

438 (emphasis added). There are widespread differences

among the lower courts as to how the McDonnell Douglas

paradigm should be adapted to discriminatory discharge

claims, not only under the Age Discrimination in

Employment Act, but also under Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 1981, the Americans with

Disabilities Act, and other federal anti-discrimination laws.

O’Connor resolved a comparatively narrow issue somewhat

unique to ADEA claims, and merely assumed without

deciding that tht McDonnell Douglas paradigm for Title VII

hiring claims could be adapted to an ADEA discharge claim.

This case presents the broader, recurring issue of what basic

standard should be applied to discharge claims brought

under the various anti-discrimination statutes.22

The conflict and confusion among the courts of

appeals is quite complex. As we set out below, there are

five distinct standards in use in the lower courts. Several

circuits, including the Sixth, have embraced one of these

standards with a fair degree of consistency. In other circuits,

the standard announced and applied varies from panel to

panel with little rhyme or reason. Evidence deemed entirely

adequate in some courts to support a finding of intentional

discrimination is dismissed in other courts as insufficient

even to establish a prima facie case. Whether particular

claimants will receive a trial on the merits, or see their

claims dismissed on summary judgment, often depends less

on the evidence they adduce than on the circuit in which

their claim was filed.

22As described above, the specific claim in the present case is

whether the petitioners were discriminated against by being

discharged in retaliation for having sought to enforce their

contractual rights free of racial discrimination, in violation of § 1981.

16

The courts of appeals generally require, to establish

a prima facie case, that the plaintiff prove (1) that he or she

was discharged,23 (2) that he or she met the basic

qualifications for the job in question, and (3) that he or she

belonged to some group protected from discrimination by

the statute involved. Disputes about whether a plaintiff

meets these requirements arise only rarely. The critical issue

is what additional elements, if any, the dismissed employee

must establish to create a prima facie case. The five

standards now in use in the courts of appeals are as follows:

Similarly Situated Comparator: The most restrictive

rule, applied by the Sixth Circuit in this and previous cases,

requires the plaintiff to identify an employee, outside the

protected group, who (1) held the same position, (2) had the

same work record, (3) reported to the same supervisor, and

(4) was not discharged.24 Sixth Circuit caselaw

understandably characterizes this rule as mandating that the

plaintiff find a "comparable" who is "similarly situated in all

respects"25or "nearly identical."26Because of the stringency

23This first element is more complex where the claim is that the

plaintiff left employment because of intolerable discrimination, in

other words, was "constructively discharged." The present case

involves actual dismissal from employment.

24Harrison v. Metro Government o f Nashville, 80 F.3d 1107, 1115

(6th Cir. 1996); Pierce v. Commonwealth Life Ins. Co., 40 F.3d 796,

802 (6th Cir. 1994); Mitchell v. Toledo Hospital, 964 F.2d 577, 582-83

(6th Cir. 1992). A more general formulation of the "similarly

situated" comparator requirement can be found in Suggs v.

Servicemaster Education Food Management, 72 F.3d 1228 (6th Cir.

1996); Timms v. Frank, 953 F.2d 281, 186 (6th Cir. 1992); Stotts v.

Memphis Fire Dept., 858 F.2d 289, 296 (6th Cir. 1988); Cooper v. City

of North Olmsted, 795 F.2d 1265, 1270 (6th Cir. 1986).

23Harrison v. Metro Government o f Nashville, 80 F.3d at 1115

("similarly situated in all respects”)(emphasis in original); Mitchell v.

Toledo Hospital, 964 F.2d at 583.

17

of this rule, discriminatory discharge claims are frequently

dismissed in the Sixth Circuit because the employer has no

such nearly identical comparator in its workforce.26 27

Replacement by Non-Group Member: The Eleventh

Circuit requires that the plaintiff prove that he was replaced

by a person who is not a member of the protected group.

Although O’Connor v. Consolidated Coin Caterers Corp.,

supra, disapproved use of this standard in ADEA cases, the

Eleventh Circuit also applies it in race discrimination

cases.28 This was the standard applied by the lower courts

in St. Mary’s Honor Center v. Hicks, 509 U.S. 502, 125

L.Ed.2d 407 (1993). Other appellate panels applying this

approach to ADEA cases since O’Connor require proof that

the plaintiff was replaced by a "younger" worker.29 Both

before and after O’Connor the Ninth Circuit has generally

required in ADEA cases that the plaintiff show that he or

she was replaced by a younger worker.30

26Pierce v. Commonwealth Life Ins. Co., 40 F.3d at 802; Ruth v.

Children’s Medical Center, 940 F.2d 662 (Table), 1991 WL 151158, at

*6 (6th Cir. Aug. 8, 1991).

21Pierce v. Commonwealth Life Ins. Co., 40 F.3d at 802; Mitchell v.

Toledo Hospital, 964 F.2d at 584; Timms v. Frank, 953 F.2d at 287;

Stotts v. Memphis Fire Dept., 858 F.2d at 296-99 (reversing finding of

intentional discrimination).

2SHawkins v. The Ceco Corp, 883 F.2d 977, 982 (11th Cir.

1989)(plaintiff "was replaced by one outside the protected class");

Noble v. Alabama Department o f Env. Mgt., 872 F.2d 361, 365 (11th

Cir. 1989)("he was replaced by a member of the majority race").

29Lawrence v. National Westminster Bank New Jersey, 98 F.3d 61,

66 (3d Cir. 1996); Denisi v. Dominick’s Finer Foods, Inc., 99 F.3d 860,

864 (7th Cir. 1996).

30Wallis v. J.R. Simplot Co., 26 F.3d 885, 891 (9th Cir. 1994);

Nesbit v. Pepsico, Inc., 994 F.2d 703, 704 (9th Cir. 1993); Cassino v.

Reichhold Chemicals, Inc., 817F.2d 1338, 1343 (9th Cir. 1987); Palmer

v. United States, 794 F.2d 534, 537 (9th Cir. 1986).

18

Plaintiffs Duties Not Abolished: The prevailing rule

in the First Circuit is that the plaintiff need only show that

following the dismissal the employer continued to need an

employee to perform the plaintiffs former duties. This can

be demonstrated by proof that the employer "sought a

replacement with roughly similar skills or qualifications,"31

actually "replaced [the plaintiff with] another with similar

skills and qualifications,"32 or "continued to have her duties

performed by a comparably qualified person."33 The race,

gender or age of any actual replacement, however, is not an

element of the prima facie case.

Non-Group Member Treated "More Favorably":

Decisions in several circuits hold that the fourth requirement

to establish a prima facie case is that the plaintiff show that

persons outside of his or her own protected group were

treated "more favorably."34

31Serrano-Cruz v. DFI Puerto Rico, Inc,, 109 F.3d 23, 25 (1st Cir.

1996); see Smith v. Stratus Computer, Inc., 40 F.3d 11, 15 (1st Cir.

1994)("her employer sought a replacement for her with roughly

equivalent qualifications").

32Mulero-Rodriguez v. Ponte, Inc., 98 F.2d 670, 673 (1st Cir. 1996);

see Goldman v. First National Bank o f Boston, 985 F.2d 1113, 1117

(1st Cir. 1993) (plaintiff "was replaced by a person with roughly

equivalent job qualifications”).

yiSmith v. F.W. Morse & Co., Inc., 76 F.3d 413, 421 (1st Cir. 1996).

3AJosey v. John R. Hollingsworth Corp., 996 F.2d 632, 638 (3d Cir.

1993) ("other employees not in a protected class were treated more

favorably"); Weldon v. Kraft, Inc., 896 F.2d 793, 796 (3d Cir.

1990)("others not in the protected class were treated more

favorably"); Fuka v. Thomson Consumer Electronics, 82 F.3d 1397,

1404 (7th Cir. 1995)(”younger employees were treated more

favorably"); Weisbrot v. Medical College o f Wisconsin, 79 F.3d 677, 681

(7th Cir. 1996)(younger employees were treated more favorably);

Cole v. Ruidoso Mun. Schools, 43 F.3d 1373, 1380 (10th Cir.

1994) ("she was treated less favorably than her male counterparts").

19

Any Evidence Supporting Inference of

Discrimination: Decisions in the Second Circuit reject any

requirement that some particular type of evidence be

adduced to establish the critical fourth element of a prim a

facie case. Rather, appellate decisions in that circuit instead

repeatedly use a more general formulation, requiring proof

that the "discharge occurred in circumstances giving rise to

an inference of discrimination on the basis of . . .

membership in th[e] class."35

Circuits With Multiplicity of Rules: There are seven

circuits within which several different standards are in use,

with no evident explanation for why a particular standard is

utilized in each particular case. Each panel in these circuits

chooses at will among these conflicting formulations, with

the outcome of the appeal often turning on which

formulation the panel opted to apply. This chaotic situation

exists in the Third,36 Fourth,37 Fifth,38 Seventh,39

35McLee v. Chrysler Corporation, 109 F.3d 130, 134 (2d Cir. 1997);

Hargett v. National Westminster Bank, USA, 78 F.3d 836, 838 (2d

1996)(discharge occurred "in circumstances giving rise to an inference

of racial discrimination”); Sutera v. Sobering Corp., 73 F.3d 13, 16 (2d

Cir. 1995)("the discharge occurred under circumstances giving rise to

an inference of age discrimination"); Quaratino v. Tiffany & Co., 71

F.3d 58, 64 (2d Cir. 1995)(”the discharge occurred in circumstances

giving rise to an inference of unlawful discrimination"); Chambers v.

TRM Copy Centers Corp., 43 F.3d 29, 37 (2d Cir. 1994)("discharge

occurred in circumstances giving rise to an inference of discrimination

on the basis of his membership in that class").

36Lawrence v. National Westminster Bank New Jersey, 98 F.3d 61,

66 (3d Cir. 1996)("plaintiff "must" prove "replacement sufficiently

younger to permit a reasonable inference of age discrimination”);

Geraci v. Moody-Tottrup, Int’l, 82 F.3d 578, 580 (3d Cir. 1996)(plaintiff

must show she was discharged "under conditions that give rise to an

inference of discrimination); Josey v. John R. Hollingsworth Corp., 996

F.2d 632, 638 (3d Cir. 1993)(plaintiff must show "other employees not

in a protected group were treated more favorably"); EEOC v. Metal

Service Co., 892 F.2d 341, 347 (3d Cir. 1990)(plaintiff must show he

was "treated less favorably than others similarly situated"); Williams

20

Eighth,40 Tenth,41 and District of Columbia Circuits.42

v. Giant Eagle Markets, Inc., 883 F.2d 1184, 1191 (3d Cir. 1989)(no

fourth requirement at all).

Bums v. AAF-McQuay Inc., 96 F.3d 728, 731 (4th Cir.

1996)("following his discharge or demotion, the plaintiff was replaced

by someone of comparable qualifications outside the protected

class1'); Mitchell v. Ball, 33 F.3d 450, 459 (4th Cir. 1994)("the position

remained open to similarly qualified applicants after plaintiffs

dismissal"); Lawrence v. Mars, Inc., 955 F.2d 902, 905-06 (4th Cir.

1992);("evidence whose cumulative probative force supports a

reasonable inference that his discharge was discriminatory").

MSingh v. Shoney’s, Inc., 64 F.3d 217, 219 (5th Cir. 1995)("after

her discharge, the position she held was filled by someone not within

her protected class"); Mayberry v. Vought Aircraft Co., 55 F.3d 1086,

1090 (5th Cir. 1995)("white employees who engaged in similar acts

were not punished similarly"); Lindsey v. Prive Corp., 987 F.2d 324,

327 (5th Cir. 1993)("the job remained open or was filled by someone

younger"); Crum v. American Airlines, Inc., 946 F.2d 423, 428 (5th Cir.

1991) (plaintiff must show that he "was replaced by someone outside

the protected class or . . . by someone younger . . . or show otherwise

that his discharge was because of age").

39Leffel v. Valley Financial Services, 1997 U.S. App. LEXIS 11359,

*17 (7th Cir. 1997)("some evidence from which one can infer that the

employer took adverse action against the plaintiff on the basis of a

statutorily proscribed criterion"); Flair v. E.J. Brack & Sons, 105 F.3d

343, 347 (7th Cir. 1997)("another, similarly situated but not of the

protected class, was treated more favorably"); Fuka v. Thomson

Consumer Electronics, 82 F.3d at 1404 ("younger employees were

treated more favorably").

40Helfter v. United Parcel Service, 1997 U.S. App. LEXIS 13590,

*13 (8th Cir. 1997)("the employer continued to attempt to fill the

position with applicants having similar qualifications"); lohnson v.

Baptist Medical Center, 97 F.3d 1070, 1072 (8th Cir. 1996)(plaintiff

was "replaced by a male . . . or the circumstances surrounding the

discharge otherwise created an inference of unlawful discrimination");

Rothmeier v. Investment Advisers, Inc., 85 F.3d 1328, 1333 n.7 (8th Cir.

1996)(plaintiff "was replaced by a younger person after his dismissal").

21

The coexistence of these widely differing standards within a

given circuit leaves litigants in considerable uncertainty as to

their respective burdens, and invites district and appellate

judges to select whichever standard will yield the result they

may for other reasons favor in a particular case. We have

set out in the notes above decisions in these circuits utilizing

these differing standards.

The difference among the standards being applied in

the circuit courts is widely recognized. The Seventh Circuit,

for example, has expressly rejected, in an ADA case, the

Sixth Circuit requirement that a plaintiff identify an

identical, but non-discharged, non-group member:

[PJroof that persons not disabled . . . were treated

more favorably than the plaintiff . . . is certainly one

of the most obvious ways to raise an inference of

discrimination . . . . It should not be understood as

the only means of doing so, however. [Plaintiff] . . .

occupies a position of significantly greater

n Greene v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 98 F.3d 554, 558 (10th cir.

1996)("a younger person replaced [him]"); Reynolds v. School District

No. 1 Denver, Colorado, 69 F.3d 1523, 1534 (10th Cir. 1995)("the

position remained open or was filled with a non-minority”); Cole v.

Ruidoso Man. Schools, 43 F.3d at 1380 (plaintiff "was treated less

favorably than her male counterparts"); Trujillo v. Grand Junction

Regional Center, 928 F.2d 973, 977 (10th Cir. 1991)("after she was

fired, her job remained open and the employer sought applicants

whose qualifications were not better than her qualifications); Allen v.

Denver Public School Board, 928 F.2d 978, 985 (10th Cir.

1991)("Nonminorities in the same or similar situations were not

disciplined the same or similarly").

i2Neuren v. Adduci, Mastriani, Meeks & Schill, 43 F.3d 1507, 1512

(D.C. Cir. 1995)("replacement by a person of equal or lesser ability

who is not a member of a protected class or, alternatively, the

position remains open after termination"); Williams v. Washington

Metropolitan Area Transit Authority, 1987 U.S. App. LEXIS 17587 *3

(D.C. Cir. 1987)("white employees were retained in comparable

circumstances").

22

responsibility and discretion than that of most . . .

employees. When cited for purported shortcomings

in her performance, she may find it difficult to find

evidence of disparate treatment in criticisms that are

intertwined with the unique aspects of her position.

But there may be other circumstances that bespeak

discrimination.

Leffel v. Valley Financial Services, 1997 U.S. App. LEXIS

11359, *18-*19 (1997). That same decision also "disavowed

. . . cases . . . suggesting that a Title VII plaintiff must show

that she was replaced by someone of a different race, sex,

and so on." Id. at *17. The Tenth Circuit, in requiring only

that a discharged employee prove that someone was hired in

her place after she was fired, acknowledged:

Other courts have developed stricter tests; for

example, some courts have held that . . . plaintiff

must show that the employer either assigned a non

minority person to her job or retained non-minority

employees having comparable or lesser qualifications.

Brown v. Parker-Hannifin Corp., 746 F.2d 1407, 1410 n.3

(10th Cir. 1984).

The circumstances of the instant case well illustrate

the practical consequences of the differing standards in use

in various federal courts. Because of petitioners’ unique

circumstances—as black grievants who had successfully

raised racial discrimination in discipline under a collective

bargaining agreement—no white employee could be found

who was similarly situated. Thus petitioners could not

satisfy the Sixth Circuit’s similarly situated comparator

requirement. Also, because petitioners were part of a larger

pool of mechanics, no particular individual was hired to

replace them when they were dismissed; thus they could not

23

have met the Eleventh Circuit’s replacement requirement.43

On the other hand, petitioners clearly would satisfy

the First Circuit requirement that they show that their

employer continued to need workers with their particular

skills.44 The Second Circuit requirement that a dismissed

worker offer some evidence supporting an inference of

discrimination would also be satisfied,45 for, as the

dissenting judge below noted at length, there was a

substantial body of such evidence in this case, albeit not the

very particular type of evidence required by Sixth Circuit

caselaw. (App. at pp. 7a-10a.)

B The Decision Below Is In Conflict With Decisions of

This Court.

The particular standard applied by the Sixth Circuit

conflicts in several distinct ways with this Court’s decisions

regarding proof of intentional discrimination.

First, and most fundamentally, the imposition of a

rigid formula as a condition for establishing a prima facie

case, for demonstrating pretext, or for proving the ultimate

fact of discriminatory intent is at odds with this Court’s

repeated admonitions that the McDonnell Douglas analysis

is not to be mechanically applied in all cases, but is only to

be used as a convenient tool where appropriate. See, JFumco

Construction Corp. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567, 577 (1978);

] United States Postal Service Board of Governors v. Aikens,

460 U.S. 711, 715 (1983); St. Maty’s Honor Center v. Hicks,

125 L.Ed.2d at 424. Rather, the task of the fact-finder is to

43See note 28, supra. See abo MacDonald v. Delta Air Lines, Inc.,

94 F.3d 1437, 1441-42 (10th Cir. 1996) (dismissed airplane mechanic

could not establish a prima facie case where no one was hired to

replace him.)

44See note 31, supra.

45See note 35, supra.

24

determine whether, when the evidence is viewed as a whole,

an inference of intentional discrimination (and/or retaliation)

may be drawn. Id.

As this Court held in Patterson v. McLean Credit

Union, 491 U.S. 164, 187-88 (1989):

Although petitioner retains the ultimate burden of

persuasion, our cases make clear that she must also

have the opportunity to demonstrate that

respondent’s proffered reasons for its decision were

not its true reasons. . . . In doing so, petitioner is not

limited to presenting evidence of a certain type. . . .

The evidence which petitioner can present in an

attempt to establish that respondent’s stated reasons

are pretextual may take a variety of forms. . . . She

may not be forced to pursue any particular means of

demonstrating that respondent’s stated reasons are

pretextual. It was, therefore, error for the District

Court to instruct the jury that petitioner could carry

her burden of persuasion only by showing that she

was in fact better qualified than the white applicant

who got the job.

(Emphasis added.) The Sixth Circuit violated this cardinal

rule by holding that petitioners could prevail only by

"presenting evidence of a certain type," i.e., that there were

comparable white employees who were not discharged under

similar circumstances.

By applying such a rule, the court of appeals affirmed

the grant of summary judgment and deprived the petitioners

of their right to have a jury determine whether the evidence

as a whole led to an inference of discrimination. Once

again, the approach of the Sixth Circuit is in sharp contrast

to and conflicts with that of the Second Circuit, whose rule

permits the consideration of all of the evidence to determine

whether there were circumstances giving rise to an inference

of discrimination. Not surprisingly, the results in the two

circuits are dramatically different; the Second Circuit

25

strongly discourages the granting of summary judgment in

employment discrimination cases,'46 while in the Sixth

Circuit they are granted regularly by district courts47 and

affirmed routinely by the court of appeals.48

46See, e.g., Gallo v. Prudential Services, 22 F.3rd 1219 (2nd Cir.

1994) Henry v. Daytop Village, 42 F.3d 89 (2d Cir. 1994).

47 See, e.g., Shelmon-Murchison v. Gerber Products Company, 1996

U.S. Dist., LEXIS 20735, at *1 (S.D. Mich. Sept. 13, 1996)(no

showing of "nearly identical" comparable that was similarly situated

in all respects, i.e., same supervisor, subject to same standards,

engaged in same conduct); Perkins v. Regents of the University o f

Michigan, 934 F.Supp. 857 (S.D. Mich. 1996)(no showing of

comparables); Marhtel v. Bridgestone /Firestone, Inc., 926 F.Supp. 1293

(M.D. Tenn. 1996)(same); Ahmed v. N.C. Servo Technology, Corp.,

1996 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 6621, at *1 (E.D. Mich. 1996)(same); Sinclair

v. ATE Management & Service Company, Inc., 1996 U.S. Dist. LEXIS

19921, at *1 (E.D. Mich. Nov. 27, 1996)(same); Thomas v. Hoyt,

Brumm & Link, Inc., 910 F.Supp. 1280 (E.D. Mich. 1994)(same);

Steward v. BASF Corporation, 1994 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 10261, at *1

(W.D. Mich. June 7, 1994)(no showing that plaintiff qualified for

position or of comparable treated differently); Bryer v. Hubert

Distributors, Inc., 1991 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 14370, at *1 (E.D. Mich.

May 13, 1991)(same); Toyee v. Janet Reno, 940 F.Supp. 1081 (E.D.

Mich. 1991)(same); Terwilliger v. GMRI, Inc., 952 F.Supp. 1224 (E.D.

Mich. 1997)(same).

48 A review of decisions by the Sixth Circuit from January, 1996,

through March, 1997, reveals that out of forty-eight cases surveyed,

the court affirmed district court grants of summary judgment for the

defendant on the merits in thirty-two cases. Of the remaining sixteen,

six decisions affirmed summary judgment for defendants on

procedural or jurisdictional grounds, two decisions affirmed in part

and reversed in part summary judgment for the defendant, and the

other eight were favorable to the plaintiff. Most of the decisions

were summary affirmances without published opinions. See, e.g.,

Palmer v. Health Care and Retirement, Inc., 1997 WL 135451 (6th Cir.

1997); Laughlin v. United Telephone-Southeast, Inc., 107 F.3d 871

(Table), 1997 WL 52921 (6th Cir. 1997); Wilson v. Wells Aluminum

Corp., 107 F.3d 12 (Table), 1997 WL 87218 (6th Cir. 1997); LaPointe

v. United Autoworkers Local 600, 103 F.3d 485 (6th Cir. 1996); White

26

Second, the Sixth Circuit standard is inconsistent with

the very idea of a prima facie case articulated in McDonnell

Douglas and its progeny. The prima facie case required by

this Court’s decisions delineates the burden of production

imposed on a plaintiff before consideration of any reasons an

employer might proffer for a disputed employment action.

The burden on the plaintiff is to adduce sufficient evidence

to warrant a presumption of discrimination "if the employer

is silent in the face of the presumption." Texas Dept, of

Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. at 254; see Fumco

Construction Corp. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567, 576 (1978)(prima

facie case met by evidence which, "if such actions remain

unexplained," would support inference of discrimination.)

The Sixth Circuit’s insistence on evidence regarding a

"comparable" white employee, however, requires a plaintiff

to anticipate and respond to an employer’s proffered

explanation as part of his or her prima facie case. Under the

Sixth Circuit’s rule, the "similarly situated" white employee

regarding whom a plaintiff must adduce evidence is a worker

who, if he or she existed, would fall within the same

standard or rule invoked by the employer to explain its

v. United Autoworkers Local 600, 103 F.3d 485 (6th Cir. 1996); Burrell

v. Providence Hosp., 104 F.3d 361 (Table), 1997 WL 729281 (6th Cir.

1996); Steele v. Electronic Data Systems Corp., 103 F.3d 131 (Table),

1996 WL 690142 (6th Cir. 1996); Rowls v. Runyon, 100 F.3d 957

(Table), 1996 WL 627712 (6th Cir. 1996); Wathen v. Lexmark Intern,

Inc., 99 F.3d 1140 (Table), 1996 WL 622955 (6th Cir. 1996); Walker

v. Runyon, 99 F.3d 1140 (Table), 1996 WL 607197 (6th Cir. 1996);

Kocsis v. Multi-Care Management, 97 F.3d 876 (6th Cir. 1996); Jobe v.

Hardaway Management Co., Inc., 98 F.3d 1342 (Table), 1996 WL

577638 (6th Cir. 1996); Jackson v. Ford Dealer Computer Services, Inc.,

95 F.3d 1152 (Table), 1996 WL 483028 (6th Cir. 1996); Gerth v. Sears,

Roebuck & Co., 94 F.3d 644 (Table), 1996 WL 464984 (6th Cir. 1996);

Wilson v. National Car Rental System, Inc., 94 F.3d 646 (Table), 1996

WL 452882 (6th Cir. 1996); Butler v. Ohio Power Co., 91 F.3d 143

(Table), 1996 WL 400179 (6th Cir. 1996); Mitchell v. White Castle

Systems, Inc., 86 F.3d 1156 (Table), 1996 WL 279863 (6th Cir. 1996);

Hale v. Secretary’, Dept, of Treasury, 86 F.3d 1156 (Table), 1996 WL

279880 (6th Cir. 1996).

27

treatment of the plaintiff. Thus the Sixth Circuit compels a

plaintiff, as part of his or her initial prima facie case, to

adduce evidence of a very specific kind to prove the

pretextuality of the employer’s possible proffered

explanation. This rule collapses the distinction between a

prima facie case and proof of pretext, and exempts

employers from the requirement of McDonnell Douglas and

Burdine that they adduce "admissible evidence" of that

explanation. Burdine, 450 U.S. at 255.

Third, under this standard the only method available

to an employee to prove pretext is to show that an employer

treated more favorably whites with comparable records,

positions and supervisors. Although that would certainly be

probative evidence, McDonnell Douglas itself makes clear

that that is not the sole type of evidence sufficient to

establish pretext.

[Plaintiff] must . . . be afforded a fair opportunity to

show that [the employer’s] stated reason . . . was in

fact pretext. Especially relevant to such a showing

would be evidence that white employees involved in

acts . . . of comparable serious [to the plaintiffs

misconduct] were nevertheless retained or

rehired. . . . Other evidence that may be relevant to

any showing of pretext includes facts as to the

[employer’s] treatment of [plaintiff] during his prior

term of employment. . . and [the employer’s] general

policy and practice with respect to minority

employment."

411 U.S. at 792 (emphasis added).

Fourth, this Court has repeatedly made clear that a

prima facie case requires only "evidence adequate to create

an inference that an employment decision was based on a[n]

[illegal] discriminatory criterion." O’Connor v. Consolidated

Coin Caterers Corp., 517 U.S. at 134 L. Ed. 2d at 432; see

Texas Dept, of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. at 253

(proof of "circumstances which give rise to an inference of

28

unlawful discrimination"); Fumco Construction Corp. v.

Waters, 438 U.S. at 576, 580 (evidence sufficient to show

discriminatory motive "more likely than not."). This is the

very formulation applied by the Second Circuit, but rejected

by the Sixth Circuit and other courts of appeals. In the

Sixth Circuit plaintiffs like petitioners who do indeed adduce

evidence supporting an inference of discrimination will

nonetheless lose as a matter of law unless they can also

adduce the requisite evidence regarding comparable "nearly

identical" whites.

Fifth, "there must be at least a logical connection

between each element of the prima facie case and the illegal

discrimination." O’Connor v. Consolidated Coin Caterers, 134

L. Ed. 2d at 438. In the Sixth Circuit one essential element

of a prima facie case is that the employer have in its employ

at least one non-minority worker who held the same position

as the plaintiff, served under the same supervisor as the

plaintiff, and had essentially the same work record as the

plaintiff. If there is no such "nearly identical" white worker

with whom a plaintiff can be compared, his or her discharge

claim fails as a matter of law. But the fact that a plaintiff

had a unique job or a unique work record is by itself

"irrelevant, so long as he has lost out because of his [race]."

O’Connor, 134 L. Ed. 2d at 438 (emphasis in the original).

In sum, the Sixth Circuit has created precisely the

sort of "rigid, mechanized [and] ritualistic" prima facie case

requirement which this Court has repeatedly disapproved.

U.S. Postal Service Bd. of Govs. v. Aikens, 460 U.S. 711, 715

(1983); Fumco, 438 U.S. at 577. The practical effect of this

standard is to delineate a class of minority, female, disabled

or over 40 workers—employees for whom there is no "nearly

identical" comparator—who can with impunity be dismissed

on the basis of race, national origin, gender, disability or

age.

29

II.

Certiorari Should Be Granted To Correct a

Fundamental Misinterpretation of the

Anti-Retaliation Protections of 42 U.S.C. § 1981

The court of appeals held that petitioners’ claim

under § 1981 must fail because they allegedly failed to

identify a specific contract provision that they enforced when

they successfully grieved the first disciplinary action against

them. App. 3a-5a. Judge Merritt, in dissent, correctly

points out that this was factually in error. App. 8a. More

fundamentally, however, the court of appeals was wrong as

a matter of law, and misinterpreted the protection provided

by section 1981 against retaliation for seeking to enforce

contractual rights free of discrimination.

It is undisputed that the petitioners successfully

exercised their contractual right to grieve a disciplinary

action against them. It is also undisputed that one of the

grounds for the successful grievance was that discipline was

being carried out in a racially discriminatory fashion.

Finally, the district court held that an inference of retaliatory

motive could be made because the the second disciplinary

hearing that resulted in petitioners’ termination was held

immediately after the grievance was won.49

Thus, petitioners alleged, and presented evidence to

support the allegation, that their employer required them to

go to second disciplinary hearings on short notice and

without the opportunity to prepare fully, and discharged

them purportedly because they refused to remain at the

hearings, in order to retaliate against them for successfully

enforcing their rights under the collective bargaining

contract to grieve a prior disciplinary action. Further, they

presented evidence that the motive behind the retaliatory

action was the fact that they had challenged the first

49App. 24a-25a. Other evidence supported the claim of

retaliation; see supra at pp. 11-12.

30

discipline, in part, because of racial discrimination in the

enforcement of the agreement.

The court of appeals’ decision fundamentally misread

section 1981. By requiring—years after a first trial on the

merits of their claims—that plaintiffs demonstrate not only

that they sought to enforce contractual rights free of racial

discrimination and were subsequently retaliated against, but

also have pleaded with particularity exactly what contractural

right was sought to be enforced, the court eviscerated the

protection against retaliation included in the statute. The

issue of the scope of section 1981’s protection against

retaliation for seeking to enforce contractural rights free of

discrimination is important and should be reviewed by this

Court.

C o n c l u sio n

For the foregoing reasons, the Petition for a Writ of

Certiorari should be granted and the decision of the court

below reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

(Counsel of Record)

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Eric Schnapper

University of

Washington

School of Law

1100 N.E. Campus Way

Seattle, WA 98195

(206) 616-3167

Ellis Boal

925 Ford Building

Detroit, MI 48226

(313) 962-2770

Attorneys for Petitioners

Appendix

[April 10, 1997]

No. 95-4171

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

JAMES T. HARVIS, JR., et al.,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

ROADWAY EXPRESS, INC.,

Defendant-Appellee.

BEFORE: MERRITT, RYAN AND SUHRHEINRICH,

Circuit Judges.

PER CURIAM. Two African-American garage

mechanics ("Plaintiffs") appeal summary judgment for their

employer, Roadway Express, Inc. ("Defendant") in this

action brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1981.1 We AFFIRM

I.

This case has a long and complicated procedural

history familiar to both parties. In summary, Plaintiffs were

notified of, yet failed to appear at, a disciplinaiy hearing

held to examine Plaintiffs’ accumulated work record.

Plaintiffs claim they were improperly notified of the

hearing.2 At the hearing, Defendant suspended Plaintiffs

1 Section 1981 states in relevant part that "[all] persons shall have

the same right . . . to make and enforce contracts . . . as is enjoyed

by white citizens. . . .”

2 Under the normal procedure for arranging disciplinary hearings

Defendant would request a mutually agreeable hearing date with the

union. Defendant would send an employee’s notice of the hearing via

certified or registered mail. In the case at bar, Plaintiffs were not

given such written notice via the mail. Instead, they were informed

verbally of their hearings on the same day that the hearings were

for two days without pay. Plaintiffs properly grieved their

suspension, arguing that they were contractually entitled to

written notice of the hearings and that such notice was

routinely provided to white employees. Without addressing

the merits of the suspensions, the grievance committee

reinstated Plaintiffs and awarded them back pay, citing

"improprieties". Defendant scheduled another disciplinary

hearing to be held approximately 72 hours after Plaintiffs

were reinstated. Defendant notified Plaintiffs of the

hearing, and Plaintiffs were not present during the

proceedings. Defendant conducted the hearing and

discharged Plaintiffs. Defendant also discharged a white

mechanic who failed to attend the hearing after receiving

proper notification.

Plaintiffs brought suit, and the district court dismissed

Plaintiffs’ § 1981 claim, holding that it did not survive

analysis under Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 491 U.S.

164 (1989).3 On appeal, this Court held that the district

court misapplied Patterson and erred in dismissing Plaintiffs’

1981 claim. Harvis v. Roadway Express, Inc., 973 F.2d 490

(6th Cir. 1992). On remand the district court granted

Defendant summary judgment, holding that Plaintiffs failed

to establish two essential elements of the McDonnell