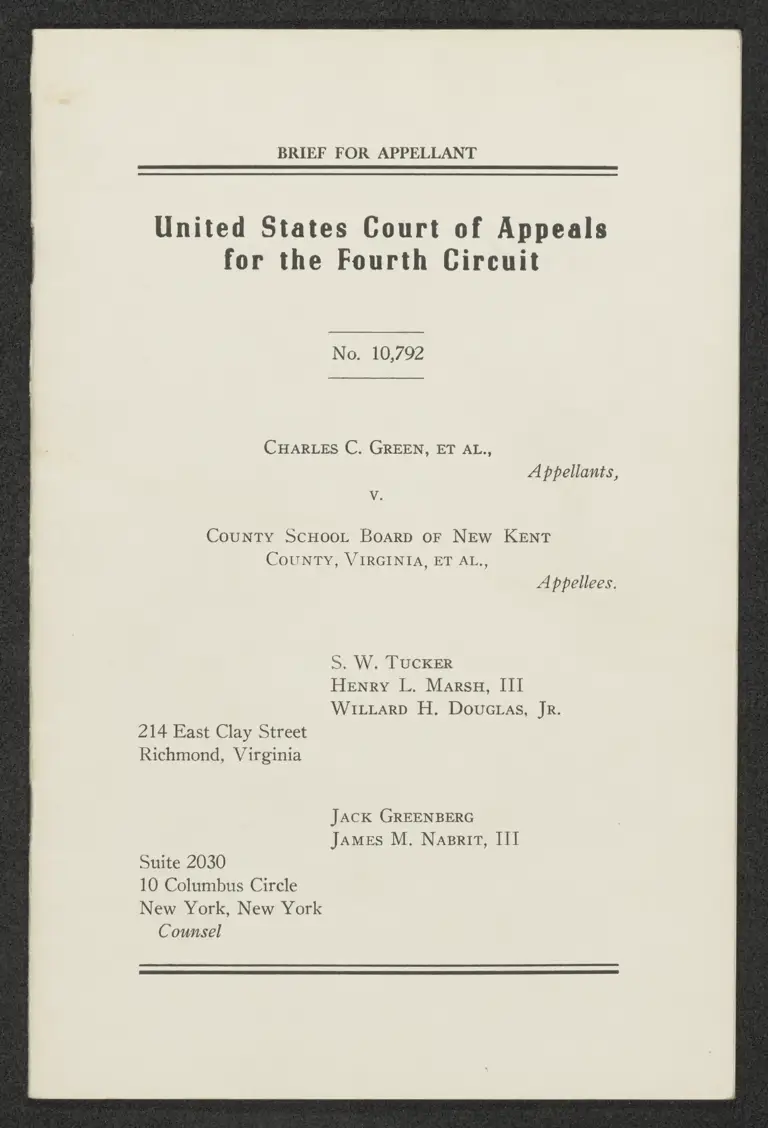

Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1967

18 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Green v. New Kent County School Board Working files. Brief for Appellant, 1967. dfc26200-6d31-f011-8c4e-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/02418128-9354-4391-96ba-8d699432dc06/brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

CHARLES C. GREEN, ET AL.,

Appellants,

Y.

County ScHooL Boarp or NEw KENT

CoUNTY, VIRGINIA, ET AL.,

Appellees.

S. WW. TuCRER

Henry L. Marsh, III

WirLLarp H. DoucLas, Jr.

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia

Jack GREENBERG

James M. Nasrir, 111

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

SP AREMENT OF THE CASE. Sn 1

URSTIONS INVOLVED eo eh a 2

SENN Or TRE FACTS. a 2

ARGUMENT Th Roem 5

I. There Is No Justification For Further Delay In Achieving

The Total Desegregation Of The New Kent County

School Syeteny Le a 5

I1. The Faculties Should Be Desegregated Immediately ............ 5

ITI. The School Board Should Be Required To Adopt A Plan

Which Will Immediately Desegregate The County’s Two

Scholes ay en i 9

ONCLUSION i 11

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Bradley v. School Board, 38217.5.103, (1965) ................o....o.. 5

Brown v. Board of Education, 3471.5. 433 (1954) ............c......c0o. 11

Cooper vo Aaron, 3531S. 1, (1058). i. lias 5

Dowell v. School Board, 244 F. Supp. 971, (W.D. Okla. 1965) .... 6

Kier v. Augusta County, 249 F. Supp. 239, (W.D. Va. 1966) .. 5, 6, 8

Rovers v, Paul, 3320.5. 198, (1968)... ici ccrrensornconsens 5

Wheeler v. Durham, ...... Fd ...., (4th Cir Tuly 5, 1966) ......-... 5

Wright v. Greensville, 252 F. Supp. 378, {E.D. Va, 1966)...........- 5.6

Wright v. School Board of Greensville County, Virginia, No. 4263

(ED. Va. Jan. 27 and May 13, 1908) .......o....cooincieiin in iicsdssnns 9

Other Authorities

Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, §§22-232.1, et seq .................... 4

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 10,792

CHARLES C. GREEN, ET AL.,

Appellants,

County ScHOoOL Boarp oF NEW KENT

CouNTY, VIRGINIA, ET AL.,

Appellees.

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This action was instituted on March 15, 1965. Plaintiffs

prayed, inter alia, that the defendants be required to bring in

a plan requiring the prompt and efficient elimination of

racial segregation in the county schools, including the elim-

ination of any and all forms of racial discrimination with

respect to administrative personnel, teachers, clerical, cus-

todial and other employees, transportation and other facil-

ities, and the assignment of pupils to schools and classrooms

(A. 2).

The defendants filed a desegregation plan on May 10,

1966 (A. 24). On May 17, the District Court ordered the

defendants to amend their plan to provide for employment

2

and assignment of the staff on a non-racial basis (A. 22).

Defendants submitted amendments to the plan on May 23,

1966 (A. 27). At the hearing on June 10th, plaintiffs filed

exceptions to said plan (A. 23). On June 28th, the District

Court approved the plan as submitted by the defendants

(A. 30). On July 27th the plaintiffs filed their notice of ap-

peal challenging the June 28 1966 order which approved the

defendants’ plan (A. 31).

QUESTIONS INVOLVED

1

Is There Justification For Further Delay In Achieving

The Total Desegregation Of The New Kent County School

System?

11

In The Absence Of Administrative Obstacles To Justify

Any Further Delay, Should The Faculties Of The County’s

Two Schools Be Desegregated Immediately ?

It

In The Absence Of Administrative Obstacles To Justify

Any Further Delay, Should The School Board Be Required

To Adopt A Plan Which Will Immediately Desegregate The

County’s Two Schools?

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

New Kent County is a rural county located in central

Virginia. Approximately 1290 children attend the county’s

public schools, about 740 of whom are Negroes and 550 of

whom are white.

Prior to and during the 1964-65 school year, the school

3

board operated but two schools—the New Kent School

which was attended by all of the county’s white pupils, and

the Geoorge W. Watkins School which was attended by all

of the County’s Negro pupils.

Other pertinent information pertaining to these schools

is contained in the following tables:

Number of Number of Pupil- Average

Grades Teachers Pupils* Teacher Class

Name of School Taught Ww N w N Ratio Size

New Kent 1-12 2% 0 552 0 22 21

George W.

Watkins 1-12 0 726 0 739 28 26

Planned Number of Variance Average

Capacity Pupils by from Number Putils

Name of School by Buildings Buildings Capacity Buses Per Bus

New Kent:

Elementary 330 367 + 37 10 54.8

High 207 185 — 22

George W. Watkins:

Elementary 420 538 +118 11 64.5

High 207 Mm. ie

* The county’s 18 Indian pupils attended a school in nearby Charles

City County by special arrangement with the Charles City School

Board. A special bus which transported these 18 pupils also transported

60 Charles City County Indian pupils.

The eleven Negro buses canvas the entire county to deliver

the county’s 739 Negro pupils to the Watkins school which

is located in the western half of the county. The ten white

buses canvas the entire county to transport the county’s 552

white pupils to the New Kent School which is located in the

eastern half of the County. (See plaintiffs’ exhibits numbers

A and B, and answers 4 and 5 to the interrogatories, A. 10.)

Prior to and during the 1964-65 school year, the county

4

operated under the Virginia Pupil Placement Act, §§ 22-

232.1 et seq., Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended.

In executing its power or purported power of enrollment

or placement of pupils in and determination of school districts

for the public schools of the county, the Pupil Placement

Board followed or approved the recommendations of the

county school board, except that the Pupil Placement Board

would refuse to deny the application of a Negro parent for

the assignment of his child to a white school and would

refuse to deny the application of a white parent for the as-

signment of his child to a Negro school. (Complaint, para-

graph 10 and Answer, paragraph 7.)

Up until September 4, 1964, no Negro pupil had applied

for admission to the New Kent School and no white pupil

had applied for admission to the George W. Watkins

School.

Over the last five years, an average of three new Negro

teachers have been employed by New Kent County and an

average of 2.6 new white teachers have been employed to

teach in New Kent County. :

Prior to March 15, 1965, petitions ‘signed by several

Negro citizens were filed with the school board asking the

school board to end racial segregation in the public school

system and urging the Board to make announcement of its

purpose to do so at its next regular meeting and promptly

thereafter to adopt and publish a plan by which racial dis-

crimination will be terminated with respect to administrative

personnel, teachers, clerical, custodial and other employees,

transportation and other facilities, and the assignment of

pupils to schools and classrooms.

On March 15, 1965, several of the plaintiffs filed this

action in the District Court.

ARGUMENT

I

There Is No Justification For Further Delay In Achieving The

Total Desegregation Of The New Kent

County School System.

New Kent County has two schools, each with 26 teachers

and identical programs of instruction (A. 11). Eleven buses

driven by Negroes canvass the entire county, transporting

the 710 Negro children to George W. Watkins School, lo-

cated in the western half of the county. All of the teachers

assigned to this school are Negroes. Ten buses driven by

white persons canvass the entire county, transporting 552

white children to New Kent School located in the eastern

half of the county. Only white teachers are assigned to this

school. Both schools accommodate pupils in excess of their

planned capacities, the Negro school being the more over-

crowded. No administrative obstacles are shown to exist, the

systematic removal of which might necessitate or justify

delay in “eliminat|[ing] racial segregation from the public

schools” Cooper v. Aaron, 358 11.8. 1,6, (1953).

II

The Faculties Should Be Desegregated Immediately

One thing obviously essential to elimination of racial

segregation from the New Kent County School system is

the desegregation of the teaching staffs of the two schools.

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. ‘103, (1965);

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965); Wheeler v.

Duthil, woeves Lol eens, (4th Cir. July 5, 1966) ; Kier

v. Auguste Conniv, 249 EF, Supp. 239, (W.D. . Va.

1966) and Wright v. Greensville, 252 F. Supp. 378,

(E.D. Va, 1966)

6

In Kier v. Augusta County, supra, the District Court,

after enjoining the board to desegregate the faculties and

administrative staffs completely for the following (1965-

66) school year, stated:

“Some guideline must be established for the School

Board in carrying out the Court’s mandate. Insofar as

possible, the percentage of Negro teachers in each school

in the system should approximate the percentage of the

Negro teachers in the entire system for the 1965-66

school session. Such a guideline can not be rigorously

adhered to, of course, but the existence of some standard

is necessary in order for the Court to evaluate the suf-

ficiency of the steps taken by the school authorities pur-

suant to the Court's order. A similar standard was

adopted by the District Court in deciding the school

desegregation suit involving Oklahoma City. Dowell v.

School Bd., 244 F. Supp. 971, 977-78 (W.D. Okla,

1965).”

In Wright v. Greensville, supra, adopted as the opinion in

this case, the Court, after indicating that the School Board

had to provide for the elimination of racially segregated

faculties, set forth the following standard to be applied by

the School Board in desegregating the teaching staffs:

“Token assignments will not suffice. The elimination of

a racial basis for the employment and assignment of

staff must be achieved at the earliest practicable date.

The plan must contain well defined procedures which

will be put into effect on definite dates.”

In the face of these admonitions, the defendants on the

6th of June, 1966, proposed to the Court that it would adhere

to the following procedures:

“1. The best person will be sought for each position

without regard to race, and the Board will follow the

policy of assigning new personnel in a manner that will

7

work toward the desegregation of faculties. We will not

select a person of less ability just to accomplish desegre-

gation,

2. Institutions, agencies, organization, and individ-

uals that refer teacher applicants to the school system

will be informed of the above stated policy for faculty

desegregation and will be asked to so inform persons

seeking referrals,

3. The School Board will take affirmative steps to

allow teachers presently employed to accept transfers

to schools in which the majority of the faculty members

are of a race different Irom that of the teacher to be

transferred.

4. No new teacher will be hereafter employed who is

not willing to accept assignment to a desegregated

faculty or ina desegregated school.

5. All workshops and in-service training programs

are now and will continue to be conducted on a com-

pletely desegregated basis.

6. All members of the supervisory staff will be as-

signed to cover schools, grades, teachers and pupils

without regard to race, color or national origin.

7. All staff meetings and committee meetings that

are called to plan, choose materials, and to improve the

total educational process of the division are now and

will continue to be conducted on a completely desegre-

gated basis.

8. All custodial help, cafeteria workers, maintenance

workers, bus mechanics and the like will continue to be

employed without regard to race, color or national

origin,

9. Arrangements will be made for teachers of one

race to visit and observe a classroom consisting of a

teacher and pupils of another race to promote acquaint-

ance and understanding.”

8

As pointed out by the plaintiffs in their exceptions to the

above plan, these provisions merely constitute a refusal by

the school board to take any initiative to desegregate the

faculties of its two schools (A. 29). Under this plan, the

board need not assign any teachers to schools with teachers

of the opposite race. Under this plan, the board might take

twenty or even thirty years to complete the desegregation of

its faculties.

These provisions fall far short of the standard established

by the Court in Kier v. Augusta County, supra. Moreover,

they do not contain “well-defined procedures which will be

put into effect on definite dates.” Even the token assign-

ments which the District Court below had warned would not

suffice, are not required by this plan.

In condemning proposals (not unlike those finally ap-

proved for New Kent) submitted by the Greensville County

School Board, the District Court in a May 11, 1966 opinion

had declared:

“The plan has no well-defined procedures which will be

put in effect on definite dates. It contains no assurance

that the present pattern of allocation of staff on a racial

basis will ever be changed. Its basic deficiency is the

transfer of responsibility from the school board to

individual teachers. It thrusts upon the teachers the

onus of discharging the school board’s responsibility to

allocate the faculty on a non-racial basis.” (A. 49)

In approving the New Kent plan, the District Court made

the following comments:

“The plan for faculty desegregation is not as definite

as some plans received from other school districts. The

court 1s of the opinion, however, that no rigid formula

should be required. The plan will enable the school board

9

to achieve allocation of faculty and staff on a non-racial

basis. The plan and supplement satisfy the criteria men-

tioned in Wright v. School Board of Greensville

County, Virginia, No. 4263 (E.D. Va., Jan. 27 and

May 13,1966).

The New Kent Plan clearly shifts the onus of the board’s

responsibility to the individual teacher. Other than the bold

assertion in the opinion, the Court does not attempt to

demonstrate how the New Kent plan satisfies the criteria

in the Wright opinion or otherwise satisfies the require-

ments of the law.

In view of the ease with which this record demonstrates

that the faculties of the two schools could be desegregated

and the absence of any administrative obstacles to the im-

mediate total desegregation of the teaching staffs of both

schools, the District Court had no authority to approve a

plan which is certain to create administrative problems and

prevent the elimination of the racially segregated faculties

“at the earliest practical date.”

III

The School Board Should Be Required To Adopt A Plan Which Will

Immediately Desegregate The County’s Two Schools

Under the Pupil Placement Board procedure, the parents

of white and Negro pupils have been afforded an unrestricted

choice between having their children attend white and

Negro schools since 1956. During this time, not a single ap-

plication was made for the transfer of any child to the

school attended by pupils of the opposite race.

Notwithstanding the obvious ease with which the school

system could be desegregated by the adoption of a geo-

graphical zoning plan, the school board selected the means

10

to accomplish the desegreation of the schools which was

least likely to work in New Kent County.

The key provisions of the plan are as follows:

1

“ANNUAL FREEDOM oF CHOICE OF SCHOOLS

A. The County School Board of New Kent County

has adopted a policy of complete freedom of choice to be

offered in grades 1, 2, 8,9, 10, 11, and 12 of all schools

without regard to race, color, or national origin, for

1965-66 and all grades after 1965-66.

Por

V1

OVERCROWDING

A. No choice will be denied for any reason other than

overcrowding. Where a school would become over-

crowded if all choices for that school were granted,

pupils choosing that school will be assigned so that they

may attend the school of their choice nearest to their

homes. No preference will be given for prior attendance

at the school.

B. The Board plans to relieve overcrowding by build-

ing during 1965-66 for the 1966-67 session.”

These provisions operate as limitations on the Pupil Place-

ment procedure which had demonstrated that a free choice

procedure in New Kent County would not result in de-

segregated schools.

Moreover, the school board failed to show any adminis-

trative obstacles which would justify any delay in the im-

mediate total desegregation of its two schools.

In the opinion adopted in this case, the Court stated:

“This circuit has recognized that local authorities

should be accorded considerable discretion in charting

a route to a constitutionally adequate school system.

11

Freedom of choice plans are not in themselves invalid.

They may, however, be invalid because the ‘freedom

of choice’ 1s illusory. The plan must be tested not only

by its provisions, but by the manner in which it operates

to provide opportunities for a desegregated education.

In this respect operation under the plan may show that

the transportation policy or the capacity of the schools

severely limits freedom of choice, although provisions

concerning these phases are valid on their face.”

The instant plan clearly does not meet the test of the principle

enunciated by the Court below.

In view of the time which has elapsed since the 1954

Brown decision, and the failure of the board to eliminate

the segregated system it has created, this board should now

be required to immediately desegregate the two schools

under its jurisdiction.

CONCLUSION

This record shows the school board still operating its two

schools in open defiance of the 1954 Brown decision. Unless

the fundamental principle announced in that decision is to

be reduced to mere egalitarian pronouncements, this Court

must make it clear that local school boards must affirmatively

remove all vestiges of racial segregation from their school

systems.

Respectfully submitted,

5. W. Tucker

HENRY L. MARrsH, 111

WiLrLArp H. DoucgLas, Jr.

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia

Jack GREENBERG

James M. Nasrir, 111

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York