Deposition Subpoena for Gary Orfield

Public Court Documents

September 11, 1992

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Deposition Subpoena for Gary Orfield, 1992. c13782e7-a746-f011-8779-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/028063a5-15e5-44c0-a8d4-cc3c915dfe5b/deposition-subpoena-for-gary-orfield. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

# Te \

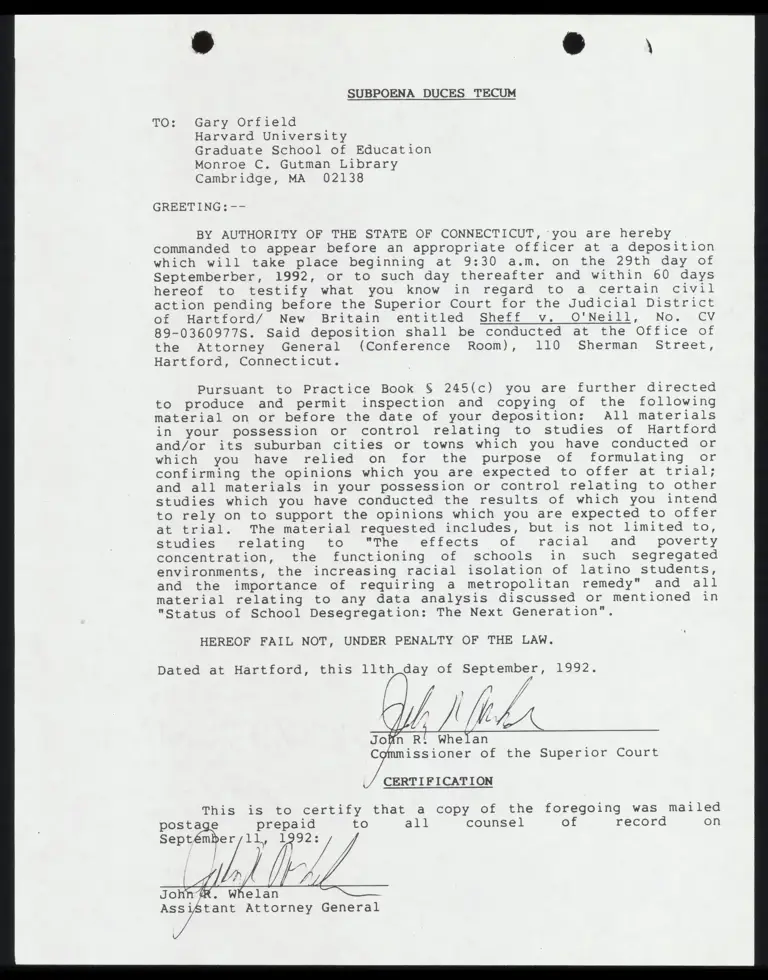

SUBPOENA DUCES TECUM

TO: Gary Orfield

Harvard University

Graduate School of Education

Monroe C. Gutman Library

Cambridge, MA 02138

GREETING: --

BY AUTHORITY OF THE STATE OF CONNECTICUT, ‘you are hereby

commanded to appear before an appropriate officer at a deposition

which will take place beginning at 9:30 a.m. on the 29th day of

Septemberber, 1992, or to such day thereafter and within 60 days

hereof to testify what you know in regard to a certain civil

action pending before the Superior Court for the Judicial District

of Hartford/ New Britain entitled Sheff v. O'Neill, No. CV

89-0360977S. Said deposition shall be conducted at the Office of

the Attorney General (Conference Room), 110 Sherman Street,

Hartford, Connecticut.

Pursuant to Practice Book § 245(c) you are further directed

to produce and permit inspection and copying of the following

material on or before the date of your deposition: All materials

in your possession or control relating to studies of Hartford

and/or its suburban cities or towns which you have conducted or

which you have relied on for the purpose of formulating or

confirming the opinions which you are expected to offer at trial;

and all materials in your possession or control relating to other

studies which you have conducted the results of which you intend

to rely on to support the opinions which you are expected to offer

at trial. The material requested includes, but is not limited to,

studies ' relating to "The effects of racial 'anéd poverty

concentration, the functioning of schools in such segregated

environments, the increasing racial isolation of latino students,

and the importance of requiring a metropolitan remedy" and all

material relating to any data analysis discussed or mentioned in

"Status of School Desegregation: The Next Generation".

HEREOF FAIL NOT, UNDER PENALTY OF THE LAW.

Dated at Hartford, this 11th day of September, 1992.

Jon R! Whelan

issioner of the Superior Court

CERTIFICATION

This is to certify that a copy of the foregoing was mailed

postage prepaid to all counsel of record on

Septémber/11, 1 ey

Lod LF

John. Whelan dp,

pi Attorney General