Ellis v. Orange County, FL Board of Public Instruction Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ellis v. Orange County, FL Board of Public Instruction Brief for Appellants, 1969. d80f6bc9-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/02825d0c-0c42-4196-acbd-c2057d3ca9ca/ellis-v-orange-county-fl-board-of-public-instruction-brief-for-appellants. Accessed January 09, 2026.

Copied!

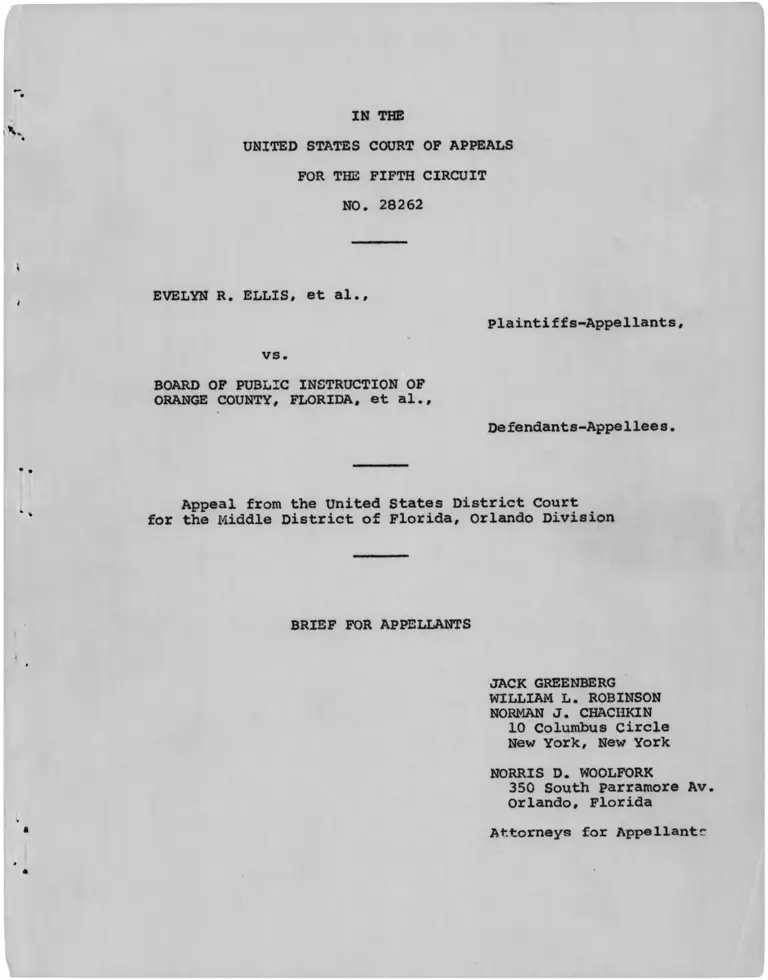

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 28262

EVELYN R. ELLIS, et al..

plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION OF

ORANGE COUNTY, FLORIDA, et al.,

De fendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Florida, Orlando Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

NORRIS D. WOOLFORK350 South parramore Av.

Orlando, Florida

Attorneys for Appellantr

INDEX

Table of Cases.................................... H

Issues presented for Review ..................... 1

Statement ........................................ 2

Argument

The Board Did Not Sustain Its Burden of Showing

That Its Plan Would Convert The orange County

Public Schools Into A Unitary Nonracial School

S y s t e m ...................................... 10

A. The Board's plan does not eliminate

racially identifiable schools in

Orange County ........................ 11

B. The Board failed to establish that

there are not feasible alternatives

to its modified freedom of choice plan 15

The District Court Erred In Holding That The

Board Was Relieved Of Any Obligation To

Desegregate Eleven All-Negro Schools ........ 19

Conclusion............................. ....... 22

Appendix A Report on Choice period and FacultyAllocation filed September 22, 1969 . 23

Page

TABLE OF CASES

Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir. 1968) . . . 20,22

page

Brice v. Landis, Civ. No. 51805 (N.D. Cal.,August

8, 1969) .................................... 12

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954);

349 U.S. 294 (1955).......................... 2,10,16

Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile, 393

F.2d 690 (5th Cir. 1968) .................... 14

Graves v. Walton County Bd. of Educ., 403 F.2d

189 (5th Cir. 1968)......................... 20

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968).......................... 2,10,11,15

Hall v. St. Helena parish School Bd., No. 26450 (5th

Cir., May 28, 1969)......................... 20

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist.,

409 F. 2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969) ................ 20

Jackson v. Marvell School Dist. No. 22, Nos. 19746

& 19797 (8th Cir., Oct. 2, 1969)(en banc) . . . 11,16

Moses v. Washington parish School Bd., 276 F. Supp.

834 (E.D. La. 1967)..........................

United States v. Board of Educ. of Baldwin County,

No. 27281 (5th Cir., July 9, 1969) ..........

United States v. Board of Educ. of Bessemer (Bessemer

I) , 396 F.2d 44 (5th Cir. 1968) .............

United States v. Board of Educ. of Bessemer (Bessemer

II) , No. 26582 (5th Cir., July 1, 1969) . . . .

United States v. Choctaw County Bd. of Educ., No.

27297 (5th Cir., June 26, 1969) ..............

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

Dist., 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969) ........

United States v. Hinds County Bd. of Educ., No.

28030 (5th Cir., July 3, 1969), amended August

28, 1969, cert, granted sub nom. Alexander v.

Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 38 U.S.L.W. 3125

(Oct. 9, 1969) ...............................

14

15

13,21

20

-ii-

Page

United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School

Dist., 410 F.2d 626 (5th Cir. 1969) ..........

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372

F.2d 836 (1966), aff'd on rehearing en banc,

380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir.), cert, denied sub nom.

Caddo Parish School Bd. v. United States, 389

U.S. 840 (1967) ..............................

United States v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ.,

395 U.S. 225 (1969) ..........................

13,20,21,

22

2

14

-iii-

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 28262

EVELYN R. ELLIS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION OF

ORANGE COUNTY, FLORIDA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Middle District of Florida, Orlando Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Issues Presented For Review

1. Whether appellees sustained their heavy burden of

demonstrating that freedom of choice would establish a unitary

school system in orange County, Florida, and that alternative

methods of desegregation, such as pairing or zoning, were not

feasible.

2. Whether the district court erred in holding that

a formerly cte jure segregated school system had fulfilled its

Constitutional obligation to establish a unitary school system

despite the fact that 55% of the school district's Negro students

remain in all-Negro schools.

Statement

This is an appeal from the denial of a Motion for Further

Relief in a school desegregation case,^ whereby plaintiffs-appel-

lants had sought to require tine Board of Public Instruction of

Orange County, Florida to implement a plan of desegregation other

than freedom of choice.

During the 1968-69 school year, the orange County public

school system consisted of 96 elementary and secondary schools en

rolling 77,336 students, of whom 13,186 (17%) were Negroes (Tr.

29).^ Of the Negro pupils, 22.18% attended predominantly white

1/ This case was first commenced in 1962. prior to that time ap

pellees maintained a completely segregated school system in

violation of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). A

plan to permit students to select the school facility nearest their

homes, regardless of their race or color, and to be made applicable

throughout the school system in several yearly steps, was approved

and entered by district court decree on May 13, 1964.

After this Court's decision in United States v. Jefferson County

Bd. of Educ., 372 F.2d 836 (1966), aff'd on rehearing en banc, 380

F.2d 385 (5th Cir.), cert, denied sub nom. Caddo parish School Bd.

v. United States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967), the parties by joint motion

filed an Amended Plan of Desegregation based on the Jefferson decree

The district court entered a decree approving the amended plan on

April 25, 1967.

December 2, 1968, appellants filed a Motion for Further Relief

based on Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968), seeking to require the district to abandon pupil assign

ment by free choice and to create a unitary school system without

racially identifiable schools. After further proceedings, the

-2-

schools (ibid.) but this was preponderantly the result of closing

some all—Negro schools between 1964 and 1968 and reassigning their

students (Tr. 14). prior to the current school year, no white

student had ever elected to attend an all—Negro school (see the

various reports on choice periods filed by appellees, passim).

Nevertheless, appellees responded to the Motion for Fur

ther Relief by proposing a modified freedom of choice plan, combine

with further closings of all-Negro schools. Although their plan

contemplated eleven schools with all—Negro student bodies (Tr. 290,i

enrolling 55% of the district’s Negro school population (Tr. 189),

appellees contended that there was no feasible way to desegregate

those schools. The district court relieved them of any obligation

to do so by holding that these schools were "not within the Graves

[v. Walton County Bd. of Educ., 403 F.2d 189 (5th Cir. 1968)],

supra, ambit of prohibited existence."

The written plan submitted by appellees is summarized

order appealed from, approving continued use of a modified free

choice plan, was entered by the district court May 13, 1969.

2/ References are to the transcript of the hearing commencing

April 30, 1969; this Court has entered an order permitting this

appeal to be heard on the original papers, without a printed

appendix.

3/ After the Motion for Further Relief was filed, the district

court January 13, 1969 ordered appellees to file by February 10,

1969 . . .either (1) a further plan for achieving desegregation

in Orange County Schools, or (2) a showing that thepresent desegregation plan will, in the immediate future,

obviate the plaintiffs' objections; or (3) a showing

that the present desegregation plan, as it now operates,

meets the requirements of the law.A proposed plan of desegregation (referred to as plan A) was filed

February 17 and rejected by the district court February 18, 1969 a;

-3-

in the margin.^1̂ It was supplemented, with the district court's

approval, by the testimony of school officials at the April 30

hearing — although they could give no reason for omitting the

specifics of their testimony from the written plan (Tr. 191).

(Thus, the district court accepted even parts of the plan which

were made meaningful only by the testimony at the hearing, e.g.,

Tr. 429).

"too vague in both its objective and methods of accomplishment.

A second plan (plan B) was filed by joint motion of February 26,

1969, but the district court on March 7 permitted both parties to

withdraw from the joint motion and again required appellees to

come forward with a plan. In response appellees presented the

plan approved below (plan C).

4/ Pupil assignment: Freedom of choice (21) combined with closing

five all-Negro schools (225,7,8 and 9).

Faculty desegregation; "Faculty desegregation will be encour

aged consistent with education needs and programs. The orange

County Board of Public Instruction will strive towards a goal

which will result in mixed faculties in all schools rather than a designation of an arbitrary percentage of races at any particular

school. Faculty desegregation will be accomplished in such a

manner that no faculty at any school will be identifiable as tailored or constituted for or in anticipation of a concentration

of students of the negro [sic] race or the white race" (214).

Construction; The district will continue to construct

"neighborhood schools" (22)•

The provisions of 223 (the district "will continue the policy

of operating one unitary school system"), 13 (the district will

carry out the plan), and 15 (the district will seek advisory

recommendations of the South Florida [Title IV] Desegregation

Center at the University of Miami) are at best precatory.

Likewise, 224 (replace present categorical diploma with a

single certificate), 6 (continue Jones Senior High with broadened

vocational program), 10 (shift a predominantly white elementary

school to portable buildings to make room for Negro students from

schools to be closed), 11 (construct a new high school in western

part of county in future), 16 (30-day choice period) and 17 (exc

ept as expressly modified, the Jefferson decree remains in force)

are all "housekeeping" provisions.

-4-

Exposition of the plan consumed most of the lengthy

hearing. After the Superintendent of Schools had described the

past history of desegregation in the orange County school system

(Tr. 22-52), the Deputy Superintendent located on a map each

of the all-Negro schools which the district proposed to close and

then described the expected dispersal of the Negro students

formerly attending that school (Tr. 76-133). His testimony re

vealed that Negro students who had attended the closed schools in

1968-69 would have their "free choice" honored only if those

choices fulfilled the expectations of the Board; otherwise, the

students' choices would be disregarded and they would be assigned

to predominantly white schools selected by the school administra-

5 /tors (e.g., Tr. 84-85).*“ These Negro students would in nearly

every instance be bussed to their new schools (e.g., Tr. 94—95),

and the school closings would also require additional portable

classrooms (e.g., Tr. 94). The total cost of bus operations and

capital investment in portable classrooms required by the closing

of these five all-Negro schools was estimated to be $506,000

($735,000 including faculty in-service training).

Deputy Superintendent Cascaddan also testified about

the policy governing faculty desegregation. Although orange

5/ The Deputy Superintendent admitted, in effect, that a free

choice plan would not achieve a nonracial unitary school sys

tem in orange County. Ha explained that although all-Negro Drew

Junior-Senior High School (closed under the plan) was to be re

opened as a technical—vocational high schools, Negro students who

had previously gone to the school would be permitted to return

only with special approval by guidance counsellors. The students

would not be given free choice, which would "promote the contin

uance of all-black Junior-Senior High School at Drew . . . ."

(Tr. 100).

-5-

County would in the future make willingness to teach in any

school in the system a condition of employment (Tr. 140) the

principals of the various schools would continue to be respon

sible for filling the vacancies on their staffs (Tr. 233), thus

controlling the racial character of each faculty. The plan

contained neither specific numerical goals for 1969-70 nor a

6/target date for complete faculty desegregation (Tr. 224-25).

The district presented Mr. John Goonen, the Director c±

Pupil placement for the school system, to justify its failure to

integrate the eleven remaining all-Negro schools (Tr. 286-354).

Mr. Goonen testified that orange County could not

afford to "consolidate" — eradicate — any more all-Negro

schools (Tr. 297-99). As to zoning, he had investigated the

7/feasibility of "spot zoning" each of the eleven all-Negro

schools so as to achieve at each school an enrollment which was

25% white (Tr. 301) 3^ Each school, in his words, "serv[ed] the

Negro residential area" in which it was located (Tr. 341) and if

a zone were drawn so as to include the requisite number of white

6/ Despite this testimony, the wording of the plan's <J14 itself, and Cascaddan's testimony that "we have not set any specific

percentages" (Tr. 227), the district court found the plan accept

able because "every school will have at least three teachers of

the race which is in the minority at that school" (Opinion of May

13, 1969, p. 15). Such a minimum was in fact achieved for 1969*7

in every school except Drew, but even a quick perusal of the

district's September, 1969 Report (subject cf a Motion to Supple

ment Record filed with this Brief) will indicate how clearly the

racial composition of the faculties continues to identify each

school by race, yet neither the plan nor the district court re

quires any further action.

7/ Defined as zoning some schools in the system while others

remained on free choice (Tr. 300).

-6

students, they would have to be bussed in to the school (e.g.,

Tr. 308); the distance they would have to travel would create

problems in terms of participation in extracurricular activities

and PTA groups (e.g., Tr. 309); they would overcrowd the facil

ities of the all-Negro schools, which could not be enlarged with

protable buildings, forcing transfer of some Negro students (e.g.

Tr. 310) by bus (e.ĝ _, Tr. 316) to other schools, which would

also often require additional portable buildings (e.g., Tr. 315} ,

Applying this hypothesis to each of the eleven all-Negro schools,

he arrived at a projected cost of "spot zoning" of one million

dollars (Tr. 349) for the transfer and housing of 5300 students

(Tr. 348). The board therefore rejected the alternative of zonin

because it considered the price and the bussing an "exorbitant"

price for desegregation (Tr. 349).

However, Mr. Goonen admitted that there were white

students living within walking distance of each all-Negro school

who could be zoned to that school (e.g., Tr. 368, 376). In

another instance, white students living approximately equidis

tant from predominantly white Robinswood Junior High and all-

Negro Carver Junior High were presently being bussed by the

board to Robinswood (Tr. 381). Importantly, Mr. Goonen admitted

the Board had considered spot zoning only the eleven all-Negro

schools, rather than drawing attendance zones for all schools

in the system (Tr. 362).

8/ 25% was an arbitrarily selected figure (Tr. 365).

7

Mr. Goonen further testified that the alternative of

pairing had been considered and rejected because of differences

in size between schools (Tr. 350) and the cost of bussing

required to effectuate pairing of the eleven all-Negro schools

— estimated at $440,000 (Tr. 351). The district did not

consider pairing schools except by division resulting in equal

numbers of grades at each of the paired schools, because to

do otherwise would result in "tremendous" splitting of

families with more than one student (Tr. 370—71). He admitted,

though, that there were possible pairings of all-Negro and

predominantly white schools (e.a., Tr. 371-72).

The district court's opinion approving the Orange

County freedom cf choice plan starts by summarizing the plan in.

considerable detail, because, the court found:

Plan "C" in its written form is somewhat

skeletal but the witnesses for the defen

dant presented in greater detail the body

of the skeleton [Opinion of May 13, 1569,

at p. 41.

As to the remaining all-Negro schools, the district court held:

The schools which will be attended solely

by Negro students are in areas which are almost, if net completely, exclusively

comprised of Negro residents. Those at

tending thos-i elementary schools are all

walk-in students excepr. for one bussed

to Holden Street Elementary and one

bussed to Washington Shores because of

physical handicaps. Zoning would not

result in any meaningful desegregation of

these schools; likewise, bringing in white

student** to the extent, of about 25% of the

total of each school would necessitate cross-bussing . . . if cross-bussing v/ere

required in connection with the eleven

schools above listed the additional cost is

-8-

estimated at $1,000,000.00 over and

above the $735,000.00 cost of Plan "C."

pairing of schools is also net feasible

because of the variance between the

facilities of schools which would nat

urally be paired, the cross-bussing

required, ar.d the cost thereof.

Considering the reasons for their present

student, racial composition and their

desegregated operation, this Court

concludes that the schools above listed are not within the Graves, supra, ambit

of prohibited existence. (opinion of

May 13, 1963, at pp. 16-18].

A Motion to Amend the district court's order approv

ing the plan was ienied June 5, 1969, and Notice of Appeal was

filed July 3, 1969.

-9-

ARGUMENT

I

The Board Did Not Sustain Its

Burden of Showing That Its Plan

Wou'.i Convert The orange County

Public Schools Into A Unitary

Nonracial School System

If the experience of the federal courts in the decad

and a half since the Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954); 349 U.S. 294 (1955), is

significant for any purpose, it demonstrates that the promise

of the Brown decisions shall never be fulfilled unless

desegregation plans are carefully scrutinized to ascertain

whether they will work to eliminate the dual system of

public education. Certainly this is the meaning of Green v.

County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 439 (1968)

which places the burden upon school boards "to come forward

with a plan that promises realistically to work, and promises

realistically to work now."

Orange County's plan — a slightly modified

freedom-of-choice plan — was not subjected to such

painstaking scrutiny by the district court. Because the

Board did not meet its burden of demonstrating that there

are not "reasonably available other ways, such for illustra

tion as zoning, promising speedier and more effective con

version to a unitary, nonracial school system, 'freedom of

-10-

choice' must be held unacceptable," Green, supra, 391 U.S. at

441, and this case returned to the district court for further

proceedings.

A . The Board's plr-n, does not eliminate racially identifiable

schools in 0reu:<j3 County

Under the Board's plan, approved below, freedom of

choice is offered all students except Negro students who

during 1968-69 attended the all-Negro schools now closed.

Those Negro students are administratively assigned to predom

inantly white schools, to which they are bussed. The result

is a school system in which the individual schools are still

clearly delineated by race.

As the September, 1969 Report of the Board (see

Appendix A, pp. 9 ̂- 9Q infra) shows, white students chose

9 / 10/almost exclusively-/ to attend predominantly white schools

and Negro students who could choose continued to choose all-

Negro schools in large numbers. 65.6% of the 1969-70 Negro

school population in orange County attends nine all-Negro and

two 99%-Negro schools.

9/ One white student attends Maxey along with 363 Negroes, and

three white students attend Webster along with 422 Negroes.

Cf. Jackson v. Marvell School Dist. No. 22, Nos. 19746 & 19797

78th Cir., October 2, 1969)(en banc)(per curiam), slip opinion ac

p 8 * "The admittance of 36 white students into a formerly all

egro school still attended by 660 Negroes cannot be said to hav<-

the effect of casting off the school's racially identifiable

cloak."

10/ The Board itself has no illusions that free choice can resul

in a unitary system. Former students at all-Negro Drew

Junior-Senior High are not to have the option of exercising a

-11-

We do not gainsay that by closing five all-Negro

schools, at substantial cost, and transporting their students to

predominantly white schools, the Board has significantly

increased the percentage of Negro students attending predominant

white schools. But this in no way diminishes the racial

identity of these "white schools"— ^ nor, within the context of

the entire system and the Board's unwillingness to assign white

students to all-Negro schools, the continued racially dual

character of Orange County public schools.

The pattern of faculty assignment underscores the

racial labels borne by each facility. As again shown by the

September 1969 Report (pp. 28 - 31 infra), every school but Drew

has at least three teachers whose race is in the minority.

However, virtually every school with a majority-white student

population has a heavily white faculty, and virtually every

majority-Negro school likewise has a heavy preponderance of

Negro faculty.

"free choice" to return to the school when it reopens as a

technical high school because "we do not want in any way to

promote the continuance of all—black Junior—Senior High School

at Drew . . . ." (Tr. 100)

11/ "The minority children are placed in the position of what

may be described as second-class pupils. White pupils,

realizing that they are permitted to attend their own neigh

borhood schools, as usual, may come to regard themselves as

•natives' and to resent the Negro children bussed into the

white schools every school day as intruding 'foreigners.' It

is in this respect that such a plan, when not reasonably

required under the circumstances, becomes substantially

discriminating in itself." Brice v. Landis, Civ. No. 51805

(N.D. Cal., August 8, 1969), slip opinion at p. 7.

-12-

The Board's plan, as approved by the court below, is

totally inadequate to deal with this situation. It states

rather vaguely that "[f]aculty desegregation will be accom

plished in such a manner that no faculty at any school will be

identifiable as tailored or constituted for or in anticipation

of a concentration of students of the negro race or the white

race" but offers no hint of when this goal will possibly be

achieved. As of this moment, the pattern of faculty assign

ments cannot be better described than "as being tailored for

a heavy concentration of Negro or white students," UnihgcL

States v. Greenwood Municipal separate School Dist., 406 F.2d

1086, 1094 (5th Cir. 1969). Yet neither the plan nor the

district court's order specifically requires further action to

be taken (Tr. 224-25).

It is extremely doubtful that, left to its own devices

and traditional methods, the Board will make rapid or substantial

progress toward the goal. For one thing, individual principals,

rather than the central administration, will continue to be

responsible for the composition of the faculty at each school

(Tr. 233) . More important, the Board had not considered manda

tory reassignment of teachers, rather than seeking volunteers

to teach in "minority" situations, to achieve faculty desegre

gation (Tr. 229). Yet the district court, which read into the

record (Tr. 228) excerpts from this Court's opinion in United

States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School Dist., 410 F.2d

626 (5th Cir. 1969), did not require reassignments.

-13-

The Board ought to be required to establish and

follow a timetable of achieving in 1970-71, United States v.

Board of Educ. of Bessemer (Bessemer I), 396 F.2d 44 (5th Cir.

1968), a totally desegregated faculty, which means that the

ratio of Negro and white personnel in each school should approx

imate, as nearly as possible, the ratio of such personnel in

the sydem as a whole. United States v. Montgomery County Bd. of

Educ., 395 U.S. 225 (1969); Bessemer II, No. 26582 (5th Cir.,

July 1, 1969).

Finally, this school district will never eliminate

racially identifiable schools under a plan which commits it to

continue its policy of constructing "aeighborhood schools" with

out any requirement that facilities be located to as to promote

desegregation, Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile, 393

F.2d 690 (5th Cir. 1968)(cf. Tr. 427). Construction of new

schools to service populations in new subdivisions (Tr. 399)

without considering the promotion of integration as a factor in

the location of new facilities will continue to produce schools

"serving" racially identifiable areas (Tr. 341), which the

district court held excused the Board from its responsibility to

desegregate those schools.

The salutary emphasis in this Court's recent opinions

on eliminating racially identifiable facilities and faculties

underlines the goal of a unitary nonracial system of public

education.

-14-

The happy day when courts retire from

the business of scrutinizing schools

is wholly dependent on school boards

facing up to the necessity of doing

away with all Negro schools and effectively integrating faculties.

That is true, no matter whether

school boards use freedom of choice,

zoning, or a combination of the two

plans.

United States v. Choctaw County Bd. of Educ., No. 27297 (5th

Cir., June 26, 1969), slip opinion at p. 4; accord, United

States v. Board of Educ. of Baldwin County, No. 27281 (5th Cir.,

July 9, 1969).

Because the plan approved below, as drafted and as

implemented this fall, fails utterly to eliminate racially

identifiable schools, the judgment below should be reversed.

B. The Board failed to establish that thete are not feasible

alternatives to its modified freedom of choice_plan

Since it proposed to retain freedom of choice for most

of the students in its school system, the Board assumed the

burden of proving that there was no other method available

which could be implemented in orange County and which would

result in "speedier and more effective conversion to a unitary

nonracial school system," Green v. County School Bd. of New.Kent

County, supra, 391 U.S. at 441.

As the Eighth Circuit has very recently put it,

[A] freedom-of-choice desegregation plan can

now receive judicial approval only if two

conditions are met. First, the plan must

offer genuine promise of promptly and effec

tively eliminating a state-imposed dual system

-15-

of schools, and second, the plan must

be the most feasible one available to the

school board, considered in light of the

circumstances present and the options

available.

Jackson v. Marvell School Dist. No. 22, Nos. 19746 & 19797 (8th

Cir., Oct. 2, 1969)(en banc)(per curiam). slip opinion at p. 7.

In Section A above we noted that the Board's plan does

not produce nor promise a unitary system because it fails to

eliminate racially identifiable schools. The Board also failed

to show that free choice was the only procedure available to it.

One of the most common alternatives to freedom of

choice is attendance zoning. This is the method of pupil assign

ment which was most generally employed — albeit in the guise of

dual overlapping zones — prior to Brown. See Moses v. Washington

Parish School Bd., 276 F. Supp. 834, 848 (E.D. La. 1967). The

Board had not projected attendance patterns if unitary attendance

zones were drawn around each school, however (Tr. 362). instead,

the Board referred to "spot zoning" or gerrymandering zones

around only the schools which would predictably remain all-Negro

under freedom of choice, to produce a 25% white enrollment at each

such school. This involved process led to a projected one million

dollar cost (Tr. 349( and an estimate that 5300 students would

have to be transferred (Tr. 348). The Board rejected spot zoning

as an alternative to freedom of choice because of the cost and

the difficulties engendered by having to transport students —

safety factors (e,g., Tr. 300, 307-08, 312) and disruption of

-16-

extracurricular activities (e.g., Tr. 300, 309).

The same factors are brought into play by the Board's

decision to close five all-Negro schools. Their students too

must be bussed to schools located further distances from their

homes (e.g.. Tr. 94-95), involving safety hazards (e.g., Tr.

113-14) and making it more difficult for secondary school

students^^ to remain after school to participate in extracur

ricular activities (ibid.). We can conclude from the Board’s

willingness to adopt this portion of the plan that these things

become considerations of sufficient magnitude to require rejec

tion of the plan only where white students are involved (e.g.,

Tr. 389-91). The Board’s expressed concern for participation

in extracurricular activities is less than convincing when one

realizes that under freedom of choice, Negro students who elect

to attend white schools must often overcome distance barriers

to take part in such activities (see Tr. 388-89). Similarly,

the Board's projected cost of one million dollars to implement

spot zoning of the eleven all-Negro schools averages some

$90,000 per school, and compares favorably with the $506,000

cost of closing five all—black facilities.

A more fundamental difficulty with the Board's proof

is that it has completely misconstrued its task. The idea is

not to select an arbitrary percentage figure and try to achieve

it in some schools, but to determine the best method — which

12/ Students in elementary schools are rarely involved in

extracurricular activities (Tr. 395-97).

-17

may include a combination of two or more approaches — of

organizing the school system so as to achieve a unitary school

system without distinction based on race. There is no evidence

in the record to support the district court's conclusion that

"[z]oning would not result in any meaningful desegregation of

these schools." The Board never described the results of

projected system-wide zoning (Tr. 362) although the raw mater

ials for making such a projection were within its possession

(Tr. 272-73)

The Board's reasons (accepted by the district court)

for rejecting pairing are also unconvincing. First, the Board

maintained that the differences in capacities between schools

which would naturally be paired were so great as to preclude

successful pairing. This was based, however, on the premise

that pairing should take place only by an equal division cf

grades between the paired schools (Tr. 350), in order to

prevent "splitting" of families with more than one pupil in

the elementary or secondary grades (Tr. 370). It is hard to

see, however, why the likelihood of such "splitting" would be

any greater if grades were not equally divided between paired

schools.

Second, said the Board (and notwithstanding its first

argument that pairing was impossible) the cost of pairing to

13/ An expert witness from the South Florida Desegregation Center

testified that with the maps locating the residence of each

student in the system and identifying him by race and grade level

which were displayed at the April 30 hearing, the Center could

have prepared a comprehensive plan for implementation in Septem

ber, 1969 (Tr. 275).

-18-

eliminate the eleven all-Negro schools v;ould be $440,000 and

would involve shifting 5300 students. Again, this cost of

closing compares very favorably with the $506,000 expense of

closing five all-Negro schools (which the district said ought

to be done anyway, even apart from considerations of integrating

the schools, e„a., Tr. 107).

The evidence introduced by the Board reveals one

thing, and one thing alone — that the Board never really

tried to find any alternatives to free choice, even though it

knew free choice would not result in a unitary school system

in Orange County.

In light of its failure in the past to bring about

anything more than token desegregation in orange county, freedom

of choice should have been sustained by the district court only

upon a clear showing by the Board that it had thoroughly inves

tigated all other methods of desegregation, and that none but

freedom of choice was capable of implementation. The halfhearted

efforts made by the Board are not enough.

II

The District Court Erred In

Holding That The Board Was

Relieved Of Any Obligation To

Desegregate Eleven All-Negro

Schools

The heart of the district court's opinion approving

the Orange County plan is the court's holding that the Board had

-19-

no obligation to desegregate eleven retaining all-Negro schools

in the system. Corseious of the fact that such a holding

directly contravened this Court's rulings in Adams v. Mathews,

403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir. 1968); Graves v. Walton County Bd. of

Educ., 403 F.2d 189 (5th Cir. 1968); see also, United States v.

Greenwood Municipal Separate School Dist., supra; Henry v.

Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist., 409 F.2d 682 (5th

Cir. 1969); United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School

Dist., supra; Hall v. St. Helena parish School Bd., No. 26450

(5th Cir., May 28, 1969); United States v. Hinds County Bd. of

Educ., No. 28030 (5th Cir., July 3, 1969), amended August 28,

1969, cert, granted sub nom. Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of

Educ., 38 U.S.L.W. 3125 (Oct. 9, 1969), the district court

purported to interpret those decisions:

Considering the reasons for their present

student racial composition and their deseg

regated operation, this Court concludes

that the schools above listed are not within

the Graves, supra, ambit of prohibited

existence.

[Opinion of May 13, 1969, at p. 18].

Appellants submit the district court's holding was

plain error. Nothing in this Court's opinions even begins to

suggest that the rule of Adams v. Mathews mandating elimination

of all-Negro schools does not apply to every school district

in this Circuit.

As best we understand its opinion, the district court

based its ruling on two theses: first, that because these

-20-

schools are located in Negro residential sections of Orange

County, they need not be desegregated, and second, that because

other schools in the County may have biracial enrollments and

there is the barest minimum faculty desegregation in all schools,

the district may ignore the rights of 65% of its Negro school-

children to a desegregated education. The court's position

cannot be sustained on either count.

Initially we note that there is agreement among the

parties that, as the Deputy Superintendent testified, orange

County's all-Negro schools are "vestiges of the dual school

system" (Tr. 417).

The first question is, is the Board relieved of its

obligation to eliminate those vestiges of the dual system because

they are located within Negro residential areas? We think not.

The very cause of this phenomenon (which is likely to continue

under the order approved below, see p. 14 supra) is the Board s

policy of constructing "neighborhood schools" in residential

subdivisions (Tr. 399) to serve racially homogeneous populations.

The idea that the Board is excused from desegregating certain

schools because they were located in accordance with its racially

discriminatory policies is entirely without merit.

The second argument seems to be that since the

situation in orange County regarding school desegregation is

not so outrageously bad as those considered in Green and in

several subsequent decisions of this Court, it is somehow

-21-

absolved and exempted from mahng more than token efforts to

eliminate the vestiges of a segregated school system that exist

in Orange County. But the Adams rule does not demand nearly the

full measure of compliance Green clearly requires in disestab

lishing the vestiges of state-imposed school segregation. In

stead, it establishes only the barest minimum standards school

boards must meet to avoid having their plans declared consti

tutionally defective as a matter of law. The fact that a formerly

racially segregated school district now has no all—Negro schools

should merely begin, not end, the court's inquiry into whether

the school board has taken steps adequate to abolish its dual,

segregated system. See United States v. Indianola Municipal

Separate School Dist., supra, 410 F.2d at 629.

CONCLUSION

For all the above reasons, the judgment of the district-

court should be reversed and the case remanded for development ana

implementation of a plan which will convert the public schools of

Orange County into a unitary school system.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

NORRIS D. WOOLFORK350 South parramore Avenue

Orlando, Florida

Attorneys for Appellants

- 2 2 -

APPENDIX A

REPORT ON CHOICE PERIOD

ORANGE COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

AMENDED PLAN OF DESEGREGATION

AS FILED WITH

CLERK OF THE COURT

PARTS I and II

SEPTEMBER 2 2 , 19 69

School_

T o ta l

Vnixo

Students

T o ta l

Negro

Students

T o ta l

Oilier

Students

T o ta l

Enrolln-

Apopka Or. 233 321

Apopka S r . 314 3 'U 1253

Boons 1864 10’} 1368

Cai’ .’ M1

1110 1110

Cherokee 222 363

C o lo n ia l 2348 8 2356

Coinray J r . l 44 l 8 1443

D m ? Tech. 11 1} 15

Edgewater 1705 201 1310

Evens 2001 16 2017

G len rid ge

l ??3 3 12=6

Howard 872 336 1228

Jaclisor* 1380 3 1583

Jones 111 11?4 1305

Lakevlsw

83/ 133 1032

Leo 310 227 1137

Lockhart Or, 632 113 751

M aitland C?3 70 363

Kcadov'ti'ook 1130 1 1151

Hensorlal 1007 223 1233

Oak Ridge 2023 1 'I3 217!}

OcGce ; 64 2 223 IO65

Robincwood 1213 10 1223

Union Park 1166 1166

k’a lk o r . 1328 31 10 1563

V in to r Pork J r , 664 162 m .

V in te r Park Sr\ 2456 n o 2378

Vfyaore Tech. 32 173 211

TOVALS 30,67!} 5 ? 537 . 10 36, >481 ,

24

Total Total Total

School

V h it c Kegro

Students Students

Other

Students

Total

Enrol lir.ent

Alema 8 7 0

0 1

B'/O

Auduhon Park 73^ 0 | 73't

Azalea Park 6 1 2 2 8 1 h

Blanknor 7 o2 3 7^5

Bonneville > * 3 0 1 * 3

B ro o k sh ire 77? 1 7 8 0

Callahan 0 «l6 8

•

hoB

Catalina 6 3 1 2 1 7 1 2

Cheney 6 8 3 0 6 8 3

Chickasaw 8 3 7 0 8 37

Columbia lfl6 0 >416

Convey 7 2 5 0 7 2 5

Cypress Pork if 5 3'» 2 1 3

Delaney 2 5 2 80 3 3 2

D ill a r d S t . 2 6 0 . 5? 3 1 3

Dcr.msrioh 8 7 8 15 833

Dover Shores 8 7 0 0 8 7 0

Dre-aJS Boko 8 1 5 8 0 8 3 5

Durrance 77? 31 8 1 0

Peel e s t on 0 8 3 7 f?7

Engolvood 7 2 6 1 7 2 7

Fern Creek 8 0 3 2 8 1 1

Forrest Park 87 13 1 0 0

Gateway if‘5 13 1 5 8

Craud Avo. 2 1 5 2 3 ? *45,0

Riavassee 7 <* 0 7«

Hillcrest 31>! 1 3 1?

liolden St. 0 7 1 2 7 1 2

B ungerford ■ 0 1 * 5 14U5

Iv e y Lano lhi h?'t f35

Kalcy !, pO

1 6 5 0!*

Ki H a m e y 8 7 1 h . 6 7 5

Bake Coro 77'* 0 77h

L sko S i l v e r 777 1 778

~ 2 5 ~

Total

White

Students

Total

Negro

Students

Total

Other

Students

Total

Enrollment

Lake Sybolia 460 Cl 431

Lake Weston 628 21 6>l?

Laker.ont 7?-7 108 833

Lancaster 3C2 2 . 384

Lockhart 4 ? 4 0 434

Lovell 858 8 663

KoCoy 737 0 737

i&gnolia 135 ' 87 133

Koxey 1 363 368

Ocoee

CO 3 333

Orange Centor 0 666 66 8

Orlo Vista 6 8 4 0 684

Pershing r/o 0 ' 770

Pir.c C&stlo 6 ? l 0 631

Pino Kills 801 .0 • 601

Pirsoloch 7 4 8 0 748

Princeton 4 l j 8 lj?7

Ray 706 5 711

Richmond Heights 0 ■ 670 670

Ridgewood Park 627 1 620

Riverside 518 6 524

Rock Lake 315 241 336

Rolling Hills 706 0 706

Sadi or 7 3 1 0 731

Shenandoah 520 13 533

Spring Lake 650 1 631

Tangclo Park 486 I38 644

Tildonville 273 135 4o8

Union Park .831 4 835 •

Wash* Shores 0 770 770

Webster Avc. 3 422 425

Wheatley 0 713 7 1 3

Windermere 5 13 3 522

- 2 6 -

School

Total

Yfhito

Studorrta

Total

Negro

Studonts

Total

Other

Students

Total

Enrollment

Vinter Garden 3 1 6 60 376

Zell.-,coed 3 2 8 1°5 5 2 3

TOTALS 3 L 3 57 6235 H3262

TOTAL COUNTY

Elementary 3*1,967 8 ,2 9 5 *13,262

Secondary 3 0 ,8 7*1 5 >577 10 3 6,118 1

TOTALS 65,6*41 13 / 6*32 1 0 79 , 7^3

\

l

27

INSTRUCTIONAL POSITIONS

28 ~

INSTRUCTIONAL POSITIONS

Secondary Schools Negro White Total

Apopka Memorial 4 62 66

Apopka Junior 8 31 39

Boone 5 85 90

Carver Junior 44 6 50

Cherokee Junior 4 46 50

Colonial '5 104 109

Conway Junior 5 49 54

Drew 21 2 23

Edgewater 4 85 89

Evans 7 85 92

Glenridge Junior 3 53 56

Howard Junior 6 • 49 55

Jackson Junior 4 58 62

Jones 72 25 97

Lake view 4 47 51

Lee Junior 4 ‘ 48 52

Lockhart Junior 3 35 38

Maitland Junior 3 40 43

Mcadowbrook Junior 3 48 51

Memorial Junior 3 54 57

M id -F la . Tech .4 67 71

Oak Ridge 7 97 104

Ocoee 6 44 50

Robinswood Junior 5. 50 55

Union Park Junior 3 50 53

Vocational 3 30 33

Walker 4 62 66

Winter Park Junior 4 34 38

Winter Park Senior 8 117 125

Wymore 9 23 32

TOTALS 265 1586 1851

7 - '3 <v h

- 2 9

.'Lot

34

31

30

30

20

31

20

27

2 8

34

15

31

13

16

16

35

3 6

32

26

28

29

32

22

26

19

29

15

32

20

30

22

33

29

31

19

26

34

36

2]

35

27

15

19

.

INSTRUCTIONAL POSITIONS

*

Elementary Schools Nearc Wl

Aloma 3 31

Audubon Park 3 28

Azalea Park & 27

Blankner 3 27

Booneville b 17

Brookshire 3 28

Callahan 15 5

Catalina 4 23

Cheney 3 25

C hickasaw ' 3 31

Columbia 3 12

Conway 4 2 7

Cypress Park 3 10

Delaney 4 12

Dillard Street 4 12

Dommerich 3 32

Dover Shores 3 33

Dream Lake 4 28

Durrance 5 21

E cc les to n • 23 5

Engelwood 3 26

Ferncreek 3 29

Forest Park 3 19

Gateway 3 23

Grand Avenue 7 12

H iaw assee 3 26

H il lores t. 3 12

Holden Street 2 6 6

Hungerford 16 4

Ivey Lane 6 24

Kaley 4 18

Killarney 3 30

Lake Como 3 26

Lake Si lver 3 28

Lake Sybelia 4 15

Lake Weston 3 23

Lakemont 3 31

Lancaster 3 33

Lockhart 3 18

Lovell 3 32

McCoy 5 22

Magnolia 4 11

Maxey 15

- 3 0 -

4

Elementary Schools Negro White Total

Ocoee 3 14 17

Orange Center 23 5 28

Orlo Vista 4 24 28

Pershing 3 31 34

Pine C a s t le 3 28 31

Pine Hills 3 29 32

Pineloch 3 29 32

Princeton 3 ' 15 18

Ray P 26. 29

"Richmond Heights 22 6 28

Ridgewood Park . 3 21 24

Riverside 3 17 20

Rock Lake 3 27 30

Rolling Hills 3 2 7 30

Sadler 3 27 30

Shenandoah 3 19 22

Spring Lake 3 25 2 8

Tangelo Park 3 27 30

Tildenville 3 14 17

Union Park 3 29 32

Washington Shores 29 3 32

W ebster Avenue 9 9 18

Wheatley 24 5 29

Windermere 3 19 22

Winter Garden 3 13 16

Zell wood 0o 22 25

TOTALS 399 1417 1816

TOTAL COUNTY:

Elementary 399 1417. 1816

Secondary 265 1 586 1851

Totals 664 3003 3667

- 2 1 -