Dallas, Texas. -- The U.S. Court of Appeals

Press Release

November 15, 1957

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Dallas, Texas. -- The U.S. Court of Appeals, 1957. 8a193257-bc92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/02ab34e3-99d5-42ef-a4ff-4a645f6f948e/dallas-texas-the-us-court-of-appeals. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

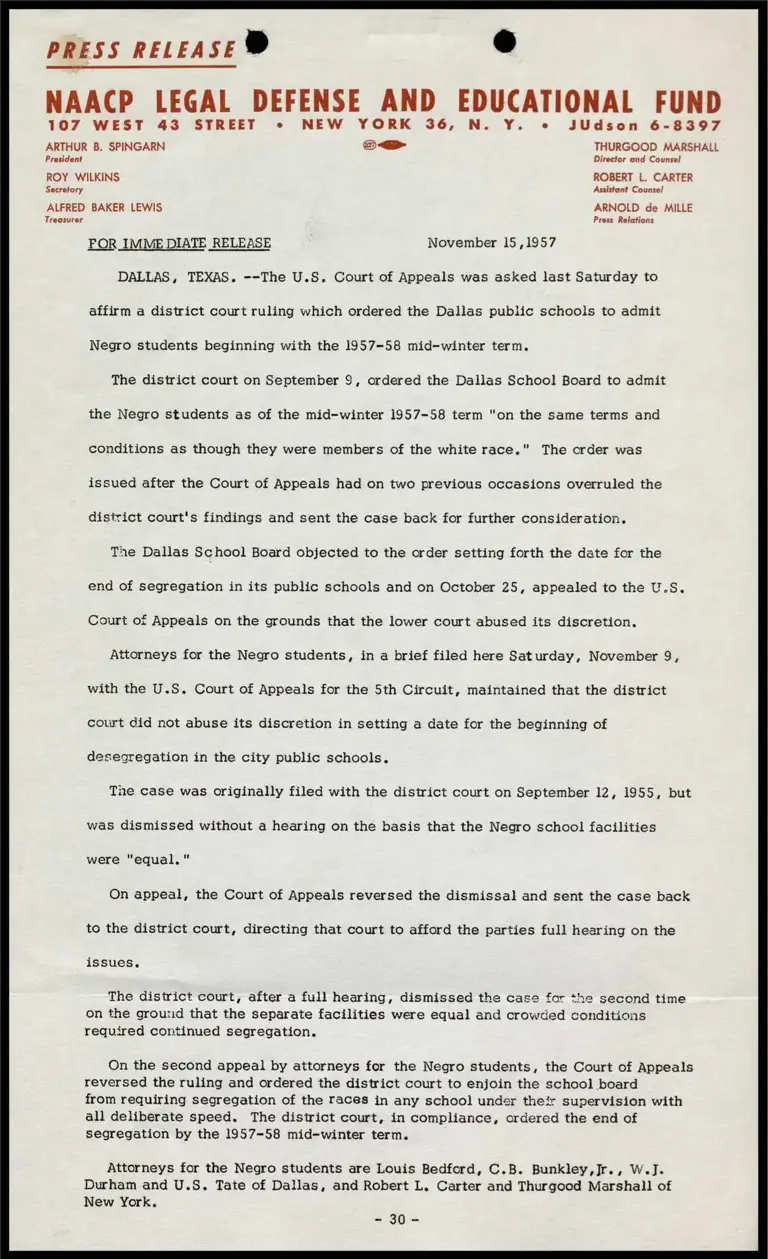

PRESS RELEASE ® *

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

107 WEST 43 STREET © NEW YORK 36, N. Y. © JUdson 6-8397

ARTHUR B. SPINGARN oa THURGOOD MARSHALL

President Director and Counsel

ROY WILKINS ROBERT L. CARTER

Secretory Assistant Counsel

ALFRED BAKER LEWIS ARNOLD de MILLE

Treasurer Press Relations

FOR IMME DIATE RELEASE November 15,1957

DALLAS, TEXAS. --The U.S. Court of Appeals was asked last Saturday to

affirm a district court ruling which ordered the Dallas public schools to admit

Negro students beginning with the 1957-58 mid-winter term.

The district court on September 9, ordered the Dallas School Board to admit

the Negro students as of the mid-winter 1957-58 term "on the same terms and

conditions as though they were members of the white race." The order was

issued after the Court of Appeals had on two previous occasions overruled the

district court's findings and sent the case back for further consideration.

The Dallas School Board objected to the order setting forth the date for the

end of segregation in its public schools and on October 25, appealed to the U.S.

Court of Appeals on the grounds that the lower court abused its discretion,

Attorneys for the Negro students, in a brief filed here Saturday, November 9,

with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, maintained that the district

court did not abuse its discretion in setting a date for the beginning of

desegregation in the city public schools.

The case was originally filed with the district court on September 12, 1955, but

was dismissed without a hearing on the basis that the Negro school facilities

were "equal,"

On appeal, the Court of Appeals reversed the dismissal and sent the case back

to the district court, directing that court to afford the parties full hearing on the

issues,

The district court, after a full hearing, dismissed the case for the second time

on the grouud that the separate facilities were equal and crowded conditions

required continued segregation.

On the second appeal by attorneys for the Negro students, the Court of Appeals

reversed the ruling and ordered the district court to enjoin the school board

from requiring segregation of the races in any school under they supervision with

all deliberate speed. The district court, in compliance, ordered the end of

segregation by the 1957-58 mid-winter term.

Attorneys for the Negro students are Louis Bedford, C.B. Bunkley,Jr., W.J.

Durham and U.S. Tate of Dallas, and Robert L. Carter and Thurgood Marshall of

New York.

=a Ora