Defense Fund Attorneys Win St. Augustine, Fla. Victory

Press Release

August 8, 1964

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 1. Defense Fund Attorneys Win St. Augustine, Fla. Victory, 1964. 0fbe322a-b592-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/02cbf13a-6eb1-4d1d-a52b-c24e70626e5c/defense-fund-attorneys-win-st-augustine-fla-victory. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

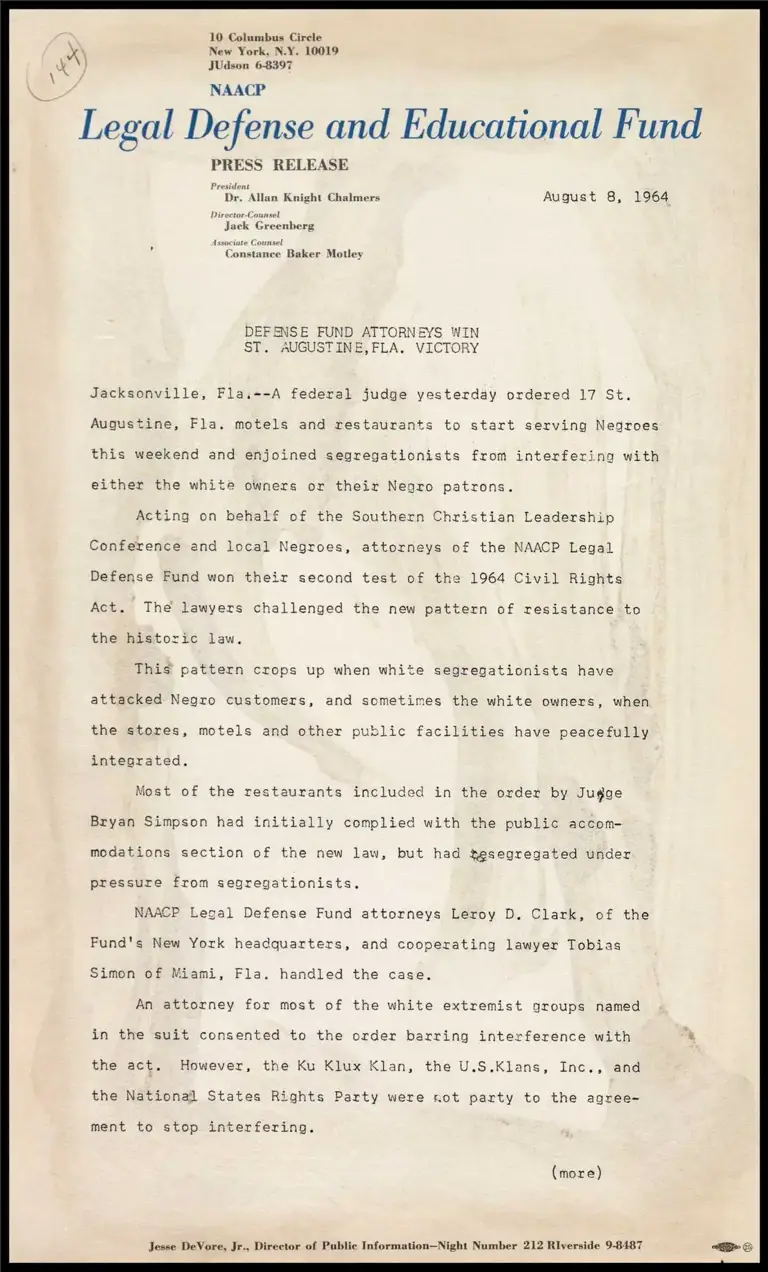

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

yo’ JUdson 6-8397

NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund

PRESS RELEASE

President

Dr. Allan Knight Chalmers August 8, 1964

Director-Counsel

k Greenberg

‘ Constance Baker Motley

DEFENSE FUND ATTORNEYS WIN

ST. AUGUSTINE,FLA. VICTORY

Jacksonville, Fla,--A federal judge yesterday ordered 17 St.

Augustine, Fla. motels and restaurants to start serving Negroes

this weekend and enjoined segregationists from interfering with

either the white owners or their Negro patrons.

Acting on behalf of the Southern Christian Leadership

Conference and local Negroes, attorneys of the NAACP Legal

Defense Fund won their second test of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act. The lawyers challenged the new pattern of resistance to

the historic law.

This pattern crops up when white segregationists have

attacked Negro customers, and sometimes the white owners, when

the stores, motels and other public facilities have peacefully

integrated.

Most of the restaurants included in the order by Jugge

Bryan Simpson had initially complied with the public accom-

modations section of the new law, but had Resegregated under

pressure from segregationists,

NAACP Legal Defense Fund attorneys Leroy D. Clark, of the

Fund's New York headquarters, and cooperating lawyer Tobias

Simon of Miami, Fla. handled the case.

An attorney for most of the white extremist groups named

in the suit consented to the order barring interference with .

the act. However, the Ku Klux Klan, the U.S.Klans, Inc., and

the National States Rights Party were sot party to the agree-

ment to stop interfering.

(more)

Jesse DeVore, Jr., Director of Public Information—Night Number 212 Riverside 9-8487 So

Defense Fund Attorneys Win -2- August 8, 1964

St. Augustine,Fla. Victory

Attorney Clark said this week that these groups will

remain defendants, and that the Legal Defense Fund will re-

quest a further hearing should they attempt to stop desegre-

gation at the motels and restaurants.

But the major group of segregationists, Halstead (Hoss)

Manucy's Ancient City Hunting Club, was specifically forbidden

from threatening, intimidating, or coercing any of the white

Mamagers or Negroes seeking service, Attorney Clark reported.

The first Civil Rights Act test case won by the Legal

Defense Fund -- the nation's first case to seek enforcement

of the bill -- came when a three judge federal court in

Atlanta, Ala, issued a temporary injunction desegregating the

Pickrick restaurant.

Pickrick owner Lester Maddox drove off three Negro cus-

tomers at gun point when they sought service,