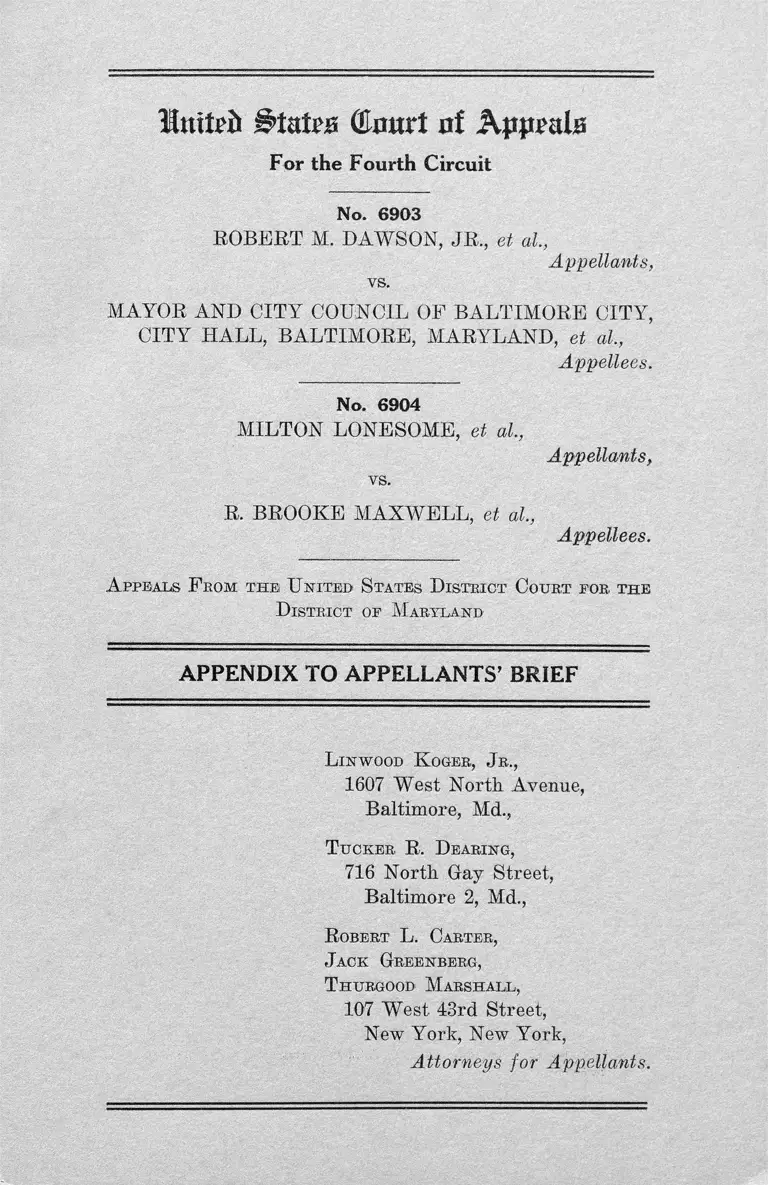

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, MD Appendix to Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1955

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, MD Appendix to Appellants' Brief, 1955. c2a21b71-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/030e4a31-8ff1-4e8d-9935-2463a7e69eb7/dawson-v-mayor-and-city-council-of-baltimore-md-appendix-to-appellants-brief. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

1 nlteh d t a t o (Emtrt o f A p p e a ls

For the Fourth Circuit

No. 6903

ROBERT M. DAWSON, JR., et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL OF BALTIMORE CITY,

CITY HALL, BALTIMORE, MARYLAND, et al,

Appellees.

No. 6904

MILTON LONESOME, et al,

Appellants,

vs.

R. BROOKE MAXWELL, et al,

Appellees.

A ppeals F rom the U nited States District Court for. the

District of Maryland

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

L inwood K oger, Jr.,

1607 West North Avenue,

Baltimore, Md.,

T ucker, R. Dearing,

716 North Gay Street,

Baltimore 2, Md.,

Robert L. Carter,

Jack Greenberg,

T hurgood Marshall,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

Attorneys for Appellants.

I N D E X

PAGE

Complaint in No. 6903 ................................................... la

Answer............................................................................ 10a

Motion for Judgment on Pleadings ......................... 15a

Stipulation ....................................................................... 16a

Answer to M otion......................................................... Ha

Complaint in No. 6904 .................................................... 18a

Answer ............................................................................. 25a

Opinion of Court Ee Vacating- Preliminary Injunc

tion, etc....................................................................... 29a

Motion for Judgment on Pleadings............................ 38a

Answer to Plaintiffs’ Motion for Judgment on

Pleadings .................................................................. 39a

Stipulation .................................................................... 10a

Excerpts From Transcript of Proceedings............. 41a

Opinion of Thomsen, D. J........................................... 14a

Motion for Final Judgment........................................... 69a

Order ................................................................................ 69a

Motion for Final Judgment......................................... 70a

Order ................................................................................. 70a

la

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

ImtTii CEmtrt nf Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

--------------------- o---------------------

No. 6903

R obert M. Dawson, Jr., et al.,

vs.

Plaintiffs,

Mayor and City Council op Baltimore City, City H all,

Baltimore, Maryland, et al.

Defendants.

----------------------o----------------------

Complaint in No. 6903

1. (a) The jurisdiction of this 'Court is invoked under

Title 28, United State Code, Section 1331, this being an

action which arises under the Constitution and laws of the

United States, viz., Fourteenth Amendment of said Con

stitution and Title 8, United States Code, Sections 41 and

43, wherein the matter in controversy exceeds, exclusive of

interest and costs, the sum of three thousand dollars

($3,000).

(b) Jurisdiction of this Court is also invoked under Title

28, United States Code, Section 1343, this being an action

authorized by law to be brought to redress the deprivation

under color of law, statute, regulation, custom and usage

of a state of rights, privileges and immunities secured by

the Constitution and laws of the United States providing

for Khe equal rights of the citizens of the United States

and of all persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States, viz., Title 8, United States Code, Sections 41 and 43.

2a

2. Plaintiffs further show that this is a proceeding for

declaratory judgment and injunction under Title 28, United

States Code, Section 2201 and Section 2202, and Rule 57,

Rules of the Civil Procedure for the District Courts of the

United States for the purpose of determining a question in

actual controversy between the parties, to w it:

(a) The question of whether this policy, custom, and

usage and practice of defendants in denying, on account of

race and color, to plaintiffs and other Negro citizens simi

larly situated, rights and privileges of attending and mak

ing use of, both beaches and both bathhouse facilities, situ

ated in the recreational park known as Fort Smallwood

Park in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, and which is

owned and operated by the City of Baltimore, Maryland,

and which is available by said municipality for the use,

comfort, convenience, enjoyment and pleasure of citizens

and residents of said City.

(b) The question of whether the custom, policy, and

usage and practice of the defendants in denying, on account

of race and color, to plaintiffs and other Negroes similarly

situated, rights and privileges of using the same bathhouse

facilities and beach advantages offered to white persons

at Fort Smallwood Park, is in violation of the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution.

3. All parties to this action are residents, citizens and

domiciled in the State of Maryland and the United States.

4. This is a class action authorized pursuant to Rule

23A of the rules of Civil Procedure for the District Courts

of the United States. The rights here involved are of com

mon and general interest to the members of the class repre

sented by the plaintiff, namely Negro citizens and residents

Complaint

3a

of the State of Maryland and of the United States who have

been denied use of recreational facilities equal to those

offered to white persons by the City of Baltimore. The

members of the class are so numerous as to make it imprac

tical to bring them all before the court, and for this reason,

plaintiffs prosecute this action in and on behalf of the class

which they represent without specifically making the said

members thereof, individual plaintiffs.

5. The plaintiffs, Bobert M. Dawson, Jr., Edith D.

Bryant, and Lacy H. Hayes are citizens of the State of

Maryland and of the United States and are residents of and

domiciled in the City of Baltimore, Maryland. They are

over the age of 21 and are taxpayers of the City of Balti

more, State of Maryland and of the United States. Plain

tiffs, Peter H. Dawson, Bobert F. Dawson, Phyllis J. Daw

son, Catherine S. Dawson, Jr., John Bichard Bryant, Har

rison James Bryant, Jr., and Vashti Murphy Smith are

citizens of the State of Maryland and of the United States

and residents of and domiciled in the City of Baltimore.

They are minors and are bringing this action by their

parents and next of kin. All of the plaintiffs are classified

as Negroes under the laws of the State of Maryland.

6. Defendant, Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, is

a body corporate, incorporated under the laws of the State

of Maryland, having power to establish and supervise

bathing beaches, bathhouse facilities and other recreational

facilities for the benefit of the citizens and residents of the

City pursuant to authority vested under Article XI-A of

the Constitution of Maryland, Article IV, Section 6(16)

and Section 6 B, Public Local Laws of Maryland and

Article 25, Section 3 of the Code of Maryland.

7. Defendants, James C. Anderson, President, George

C. Shriver, Gerald S. Wise, Samuel L. Hammerman, Bev.

Complaint

4a

Wilbur H. Waters, James H. Gorges, and Mrs. Victoria

Rysanek are members of the Board of Recreation and

Parks of Baltimore, an instrumentality of the City of

Baltimore, with authority to maintain, supervise and con

trol the operation of bathing beaches and other recrea

tional facilities maintained by the City for the benefit and

use of the citizens of the City of Baltimore pursuant to

authority vested under Section 96 of the Baltimore City

Charter, and R. Brooke Maxwell is the director of the

Bureau of Recreation and Parks, with authority, under

Section 95 of the Baltimore City Charter to direct the

operation of the Department of Recreation and Parks.

8. Defendant, Sun and Sand, Inc., is a body corporate,

incorporated under the laws of the State of Maryland. It

is a lessee from the defendants, the Board of Recreation

and Parks, and operates its concession under the super

vision and control of the Board of Recreation and Parks

in order to add to the comfort, convenience, enjoyment and

pleasure of those persons using the facilities available at

Fort Smallwood Park.

9. All the defendants are being sued in their official

and representative capacities as such.

10. Pursuant to municipal authority set forth in Sec

tion 96 of the Baltimore City Charter, defendants have

established and are maintaining and operating bathing

and recreational facilities at Fort Smallwood Park as a

part of the recreational facilities maintained and operated

by and through the City of Baltimore. This park is a

public facility which is supported out of public funds and

operated by the City to afford recreational facilities and

advantages to citizens and residents of the City of Balti

more.

Complaint

5a

11. The defendants herein are charged with the duty

of maintaining, operating and supervising the said Fort

Smallwood Park. As a part of their supervisory control

and authority with respect to Fort Smallwood Park, these

defendants are clothed and vested with the exclusive power

to promulgate and enforce rules and regulations with

respect to the use, availability and admission to said Fort

Smallwood Park to the persons who desire to use same.

12. On August 10, 1950, plaintiffs Lacy Hayes, Edith

D. Bryant, Harrison J. Bryant, Jr., John R. Bryant and

Vashti Murphy Smith sought the use of these facilities

and were denied same solely because of their race and color

while at the same time white persons were permitted the

use of said facilities without question. Admission to the

locker facilities, was refused by an attendant, to the plain

tiffs, solely because of their race and color, and Kenneth

C. Cook, President of the Sun and Sand, Inc., lessee of the

bathing house and food concessions from the City, as

serted that he was the manager of the said Park, and that

bath and beach facilities at Fort Smallwood Park were not

available to the plaintiffs because they were Negroes;

whereupon plaintiffs left after making protests.

13. On July 3, 1950, Robert M. Dawson, Jr., Peter H.

Dawson, Catherine S. Dawson Jr., and Phyllis J. Dawson,

were admitted to the only bathhouse and beach facilities

at Fort Smallwood Park, but were called from the water,

by Kenneth C. Cook, President of the Sun and Sand, Inc.,

after the Dawsons had been swimming there without in

cident for almost an hour. Robert M. Dawson, Jr., pro

tested for himself and his children, and they left.

14. On August 10, 1950, plaintiffs appealed to the Board

of Recreation and Parks asserting their right to admission

Complaint

6a

and use of all facilities of Fort Smallwood Park as resi

dents and citizens of the City of Baltimore and protesting

the refusal of the defendants to admit them because they

were Negroes.

15. On August 28, 1950, plaintiffs were advised by an

official of the Board of Recreation and Parks that they

could not be admitted to Fort Smallwood Park because

they were Negroes. Because of their refusal of entry to

Fort Smallwood Park, plaintiffs were denied their consti

tutional rights to the use of public facilities and suffered

mental anguish and embarrassment due to such refusal. On

September 15, 1950, plaintiffs appeared before the Board

of Recreation and Parks to protest their exclusion from

Fort Smallwood Park on account of race and color. No

reversal of the policy excluding plaintiffs was effected by

the Board.

16. On March 2, 1951, this Honorable Court rendered

judgment for Plaintiffs who were refused entry to Fort

Smallwood Park on August 10, 1950, and subsequently

signed an Order enjoining the defendants from excluding

plaintiffs from facilities at Fort Smallwood Park. During

the summer of 1951, by order of the Board of Recreation

and Parks, colored persons exclusively used the bathhouse

facilities at Fort Smallwood Park on certain days, while

white persons used them on all the other days.

17. On January 25, 1952 the Board of Recreation and

Parks formally voted to establish separate bathhouse and

beach facility for the exclusive use of colored persons at

Fort Smallwood Park, and to reserve the original bath

house and beach facility of 1950 and 1951 for the exclusive

use of white persons.

Complaint

7a

18. On February 29, 1952 the Board of .Recreation

and Parks passed a resolution accepting the lowest bid of

$32,354 to build a separate bathhouse for colored persons

at Fort Smallwood Park, and recommended approval to

the Board of Estimates. Subsequently, the Board of Esti

mates approved this estimate, and the separate bathhouse

for colored was built and reserved for colored.

19. On April 1, 1952 Plaintiffs’ attorney demanded by

letter to the Board of Recreation and Parks, that every fa

cility at the park be opened to everybody without any racial,

religious, or color bar. The letter of the Secretary of the

Board of Recreation and Parks in reply merely acknowl

edged the letter stating that he would keep Plaintiffs in

formed of policy decisions of the Board. Since then, the

colored bathhouse has been completed and made available,

so that one bathhouse and beach is for exclusive use of

colored persons, and the original bathhouse and beach is

for the exclusive use of white persons. The Board of

Recreation and Parks has never reversed this policy of

separate bathhouse and beach facilities for colored and

white persons.

20. Plaintiffs maintain that these separate beaches con

stitute an inequality, in that colored persons are still com

pletely excluded from the original bathhouse and beach,

and that the colored bathhouse and beach are located in a

different locality, off the bay, thus constituting physical

and psychological inequality under the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution. The policy, cus

tom and usage of defendants, and each of them, of provid

ing, maintaining and operating recreational facilities at

Fort Smallwood Park for the white citizens and residents

of the City of Baltimore, out of public funds while failing

and refusing to admit Negroes to all of these recreational

Complaint

8a

facilities, wholly and solely on account of their race and

color is unlawful and constitutes a denial of their rights to

the equal protection of the laws and of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

21. Plaintiffs, and those similarly situated and affected

and on whose behalf this suit is brought, will suffer ir

reparable injury and are threatened with irreparable in

jury in the future, by reason of the acts herein complained

of. They have no plain, adequate or complete remedy to

redress the wrongs and illegal acts herein complained of

other than this suit for a declaration of rights and an

injunction. Any other remedy to which plaintiffs and

those similarly situated could be remitted would be at

tended by such uncertainties as to deny substantial relief,

would involve multiplicity of suits, cause further irrepar

able injury and occasion damage, vexation and inconveni

ence to the plaintiffs and those similarly situated.

W herefore, Plaintiffs pray:

1. That proper process issue and that this cause be

advanced upon the docket.

2. That the Court adjudge, decree and declare the

rights and legal relations of the parties to the subject

matter here in controversy in order that such declaration

shall have the force and effect of a final order or decree.

3. That the Court enter a judgment and declare that

the policy, custom, usage and practice of the defendants

in refusing to permit Negroes to make use of both bath

houses and both beach facilities at Fort Smallwood Park,

while permitting white persons to use one bathhouse and

Complaint

9a

beach without question, solely on account of race and color,

is in contravention of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

4. That this Court issue a permanent injunction for

ever restraining the defendants and each of them, their

lessees, agents and their successors in office from denying

to plaintiffs and other Negro residents of the City of

Baltimore, the use and enjoyment of any beach or bath

house established, operated, and maintained by the City

of Baltimore, on account of race and color.

/ s / L inwood G. K oger, Jr.,

Linwood G. Koger, Jr.,

Attorney for Complainants,

1607 West North Avenue,

Lafayette 1513.

Complaint

10a

The defendants respectfully show that the Complaint

filed herein is a continuation of the litigation in Civil

Action No. 5170 in this Court. The defendants in both

actions are the same except that the Reverend Wilbur H.

Waters has taken the place on the Board of Recreation and

Parks of Dr. Bernard Harris, and Mrs. Victoria Rysanek

has taken the place on said Board of Dr. J. Ben Robinson;

five of the plaintiffs in Civil Action No. 5847 were plaintiffs

in Civil Action 5170; counsel for the plaintiffs in both

actions is the same; the legal question in both actions is

the same, to wit, whether segregation of the members of

the negro race from members of the white race in the use

of the public facilities maintained by the City of Baltimore

for bathing at Fort Smallwood Park is legal. The defend

ants assert that it is; the plaintiffs deny the legality of

such segregation.

Many of the paragraphs of the Complaint in the present

action are substantially, if not entirely, identical with the

corresponding paragraphs in Civil Action No. 5170. The

defendants refer to the pleadings in Civil Action No. 5170

and pray that they may be read in connection with this

Answer.

The Order of this Court in Civil Action No. 5170,

referred to in Paragraph 16 of the Complaint in Action

No. 5847 is dated April 6, 1951, and is as follows:

‘ ‘ Obdee

The motion of the plaintiffs for judgment on the

pleadings in the above-entitled civil action came on

to be heard on March 2, 1951, before the Honorable

W. Calvin Chesnut, Judge.

The pleadings were read and considered and

counsel for the respective parties were heard. There

is no substantial difference between the material

facts stated in the Complaint and the facts stated

Answer

11a

in the Answer. There is no difference between the

plaintiffs and the defendants as to the applicable

law. The defendants, in their Answer, expressly

recognize their obligation to furnish substantially

equal recreational facilities to negroes and whites

at Fort Smallwood Park, if they maintain recrea

tional facilities there open to either race; and defend

ants have no objection to the Court passing an order

to that effect.

It is, therefore, ordered, adjudged and decreed,

That each of the defendants is hereby perpetually

enjoined from discriminating against negroes on

account of their race or color to their prejudice in

the use of the recreational facilities maintained by

the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore at Fort

Smallwood Park.

Costs to be paid by the defendants.”

After the entry of said Order, the Board of Park Com

missioners adopted a schedule for the use of the bathing

beach at Fort Smallwood as follows:

“ Negroes to have the exclusive use of said

facilities:—

May 30 and 31,

June 21 to June 30, inclusive,

July 21 to July 31, inclusive,

August 21 to August 31, inclusive.

“ The facilities to be reserved for white persons

on all other days during the season of 1951.”

After the adoption of this schedule the bathing facilities

at Fort Smallwood were used during the season of 1951

by 13,897 white patrons and 1,143 negro patrons; the

total use for 1951 was 15,040 patrons. In the previous

Answer

12a

year, 1950, when white patrons alone used the beach, the

attendance was 42,531.

Further answering, the defendants say Fort Small

wood Park was acquired by the City in May, 1928, from

the United States Government for the sum of Fifty Thou

sand Dollars ($50,000) and contains approximately one

hundred (100) acres of land; the park is situated about

twenty (20) miles distant from the heart of Baltimore

City on a peninsula, or point, known as Rock Point, which

projects into the Patapsco River in Anne Arundel County,

Maryland. The City maintained a bathing beach on the

west side of said peninsula from 1928 until 1941. During

World War II—from 1941 to 1946—this bathing beach

was closed, primarily because of wartime restrictions, and

also because of the fact that this beach was partly washed

away. In 1947 the City constructed a bathing beach on

the east side of the peninsula, which was the one that was

used, on alternate days as aforesaid, by both negroes and

whites during 1951. In 1952 the City erected a bathing

beach on the west side of the peninsula and, beginning

May 30, 1952, opened this beach for the exclusive use of

negroes, and limited the use of the beach on the east side

for the exclusive use of the whites. The length of the

beach now used exclusively by negroes is three hundred

sixty (360) feet in length with a depth of one hundred

fifteen (115) feet. The length of the beach used by whites

is eight hundred fifty (850) feet, with a depth of fifty

(50) feet. Both beaches border on the waters of the

Patapsco River. This will appear by an examination of

Defendants’ Exhibit No. 1, filed herewith, the said exhibit

being “ General Highway Map, Anne Arundel County,

Maryland, prepared by the Maryland State Roads Com

mission, Traffic Division, in cooperation with the United

States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Public Roads,

data obtained from State-wide Highway Planning Survey” ;

Answer

13a

also by Defendants’ Exhibit No. 2, filed herewith, said

Exhibit No. 2 being a map—“ City of Baltimore,Depart

ment of Public Works, Bureau of Harbors—Approaches

to Baltimore Harbor” .

Answering’ Paragraph 12 of the Complaint, defendants

say that Sun and Sand, Inc. is a concessionaire of certain

privileges at Fort Smallwood Park and was such con

cessionaire on or about August 10, 1950, when some of

the plaintiffs visited Fort Smallwood Park and were

denied the use of the bathing facilities there situate at

that time, but, as stated in Paragraph 6 of the Answer

of these defendants in Civil Action No. 5170, the Park

Board, prior to August 10, 1950, had received no request

from negroes to use the bathing beach at said park and

such use was denied them on August 10, 1950, because no

bathing facilities had at that time been constructed for

negroes at Fort Smallwood Park. As hereinbefore stated,

the situation with reference to bathing’ facilities at said

Park is now different from what it was on August 10,

1950, in that a bathing beach for the use of negroes

exclusively has since been constructed and is now being

maintained.

Answering Paragraph 20 of the Complaint, defendants

say that neither of said bathhouses and beaches are directly

located on the bay proper. Defendants further say that

no two pieces of land or beaches are exactly alike, but

defendants deny that the facilities maintained by the City

for bathing at each of said beaches are not substantially

equal. The beach on the west side of said peninsula, used

by the negroes, has some advantages which the beach on

the east side, used by the whites, does not have; for

instance, the negro bathing beach is more conveniently

located with reference to the pier where the boat running

from the City of Baltimore to Fort Smallwood docks for

the discharge of passengers for Fort Smallwood Park.

Said bathing beach is also surrounded by picnic groves and

Answer

14a

playground facilities more conveniently located with

reference to said negro bathing beach than for the beach

which is used exclusively by white patrons. Also, im

mediately behind the beach used by white patrons is a

large swamp or lagoon, which detracts from the pleasure

of the users of the white bathing beach; the users of the

negro bathing beach do not have to contend with the dis

advantages of this swamp or lagoon. The bathhouse for

negroes has a capacity of 1,050 bathers, while the white

bathhouse can accommodate 2,944.

All facilities, other than the bathing beaches, main

tained by the City at Fort Smallwood are open to both

negroes and whites. Defendants deny that they violate

any constitutional or legal right of the plaintiffs by main

taining one beach for white patrons and the other for

negroes.

A nd n o w , h avin g f u lly answ ered , defendants pray the

Bill of Complaint be dismissed with proper costs to the

defendants.

/s / T homas N. B iddison,

Thomas N. Biddison, City Solicitor,

E dwin H arlan, Deputy City Solicitor,

/ s / A llen A. Davis,

Allen A. Davis,

Attorneys for all defendants except

Sun and Sand, Inc.

/s / David P. Gordon,

David P. Gordon,

Attorney for Sun and Sand, Inc.

Answer

15a

Motion for Judgment on Pleadings

Robert M. Dawson, Jr.; Peter H. Dawson, Minor, by

Catherine S. Dawson, Sr., Ms mother and next of kin;

Robert F. Dawson, Minor, by Catherine S. Dawson, Sr.,

his mother and next of kin; Catherine S. Dawson, Jr.,

Minor, by Catherine S. Dawson, Sr., her mother and next

of kin; Lucy H. Hayes; Edith D. Bryant; Harrison J.

Bryant, Jr., Minor, by Rev. Harrison J. Bryant, his father

and next of kin; John H. Bryant, Minor, by Rev. Harrison

J. Bryant, his father and next of kin; Vashti Murphy

Smith, Minor, by Ida Murphy Smith, her mother and next

of kin; plaintiffs herein, move the Court to enter judgment

on the pleadings filed in this case in favor of the plaintiffs

and against the defendants and assign therefore the fol

lowing reasons:

1. The complaint alleges a violation of plaintiffs’ con

stitutional rights in that defendants require racial segre

gation in the facilities which are the subject of this action.

2. The answer admits that defendants exclude plain

tiffs from these city-operated facilities to which they sought

admission solely because of their race.

3. Such racial segregation violates the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution.

/ s / L inwood G. R oger, J r .,

Linwood G. Koger, Jr.,

1607 West North Avenue,

Baltimore, Maryland.

/ s / Tucker R. Dearing,

Tucker R. Hearing,

716 North Gay Street,

Baltimore, Maryland.

/ s / Jack Greenberg,

Jack Greenberg,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York.

16a

Stipulation

(Filed June 18, 1954)

It is stipulated and agreed by and between the parties

in this case that the separate facilities in question herein

are physically equal at this time.

/ s / Linwood G. K oger, Jb.,

/ s / T uckeb. R. B earing ,

/ s / Jack Greenberg,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs.

/ s / T homas N. B iddison,

City Solicitor,

/ s / E dwin H arlan,

Deputy City Solicitor,

/ s / H ugo A. R icciuti,

Assistant City Solicitor,

/ s / Francis X . Gallagher,

Assistant City Solicitor,

/ s / F rancis X. Gallagher,

Attorneys for all defend

ants except Sun & Sand,

Inc.

/ s / David P. Gordon,

Attorney for Sun & Sand,

Inc.

17a

Now come the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore,

James C. Anderson, President, George G. Shriver, Gerald

S. Wise, Samuel L. Hammerman, Rev. Wilbur H. Waters,

James H. Gorges and Mrs. Victoria Rysanek, constituting

the Board of Recreation and Parks, R. Brooke Maxwell,

Director of the Bureau of Recreation and Parks, and

Charles A. Hook, Superintendent of Parks and Pools for

Baltimore City, Respondents, and, in answer to the Motion

heretofore filed for judgment on pleadings by the plaintiffs

herein, say:

1. That the Respondents admit the allegations con

tained in Paragraph 1 of the said Motion.

2. That the Respondents deny they excluded the plain

tiffs from the City-operated facilities, and aver that they

merely required the plaintiffs to use the bath house and

beach so designated for people of their race.

3. That the Respondents deny the allegations contained

in Paragraph 3 of the said Motion.

W herefore, having answered said Motion, Respondents

pray that it may be denied, with proper costs.

/s / T homas N. B iddison,

Thomas N. Biddison,

City Solicitor,

/ s / E dwin H arlan,

Edwin Harlan,

Deputy City Solicitor,

/ s / H ugo A. R icciuti,

Hugo A. Ricciuti,

Assistant City Solicitor,

/ s / F rancis X . Gallagher,

Assistant City Solicitor,

Attorneys for Respondents.

Answer to Motion

18a

— ------ ------ o------------------

No. 6904

M ilton L onesome, et al.,

vs.

Plaintiffs,

Sidney D. Peveeley, Chairman, et al.,

Defendants.

----------------------o----------------------

Complaint in No. 6904

1. (a) The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1331, this being an

action which arises under the Constitution and laws of

the United States, viz., Fourteenth Amendment to said

Constitution and Title 8, United States Code, Sections

41 and 43, wherein the matter in controversy exceeds,

exclusive of interest and costs, the sum of Three Thousand

Dollars ($3,000).

(b) Jurisdiction of this Court is also invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1343, this being

an action authorized by law to be brought to redress the

deprivation under color of law, statute, regulation, custom

and usage of a state of rights, privileges and immunities

secured by the Constitution and laws of the United States,

viz., Title 8, United States Code, Sections 41 and 43.

2. Plaintiffs further show that this is a proceeding

for a temporary restraining order, interlocutory, and

permanent injunction and declaratory judgment under

Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2201-2202, and Rules

57 and 65, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for the pur

19a

pose of determining the questions in actual controversy

between the parties, to wit:

(a) Whether the policy, custom and usage, and practice

of Defendants in denying, on account of race and color,

to Plaintiffs and other Negroes similarly situated, rights

and privileges of using, without being racially segregated,

all recreational facilities, situated in Sandy Point State

Park and Beach, in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, which

area is made available by the state for the use, comfort,

convenience and enjoyment of its citizens and residents,

is in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States?

(b) Whether the facilities offered Plaintiffs and the

class they represent at Sandy Point State Park and Beach

afford Plaintiffs the equal protection of the law where

the facilities set apart for the Plaintiffs and the class they

represent are physically inferior and psychologically

stigmatize Plaintiffs in a manner which makes it impossible

for them to obtain recreation equal to that afforded white

persons?

3. All parties to this action are citizens of the United

States and are domiciliaries of the State of Maryland.

4. This is a class action authorized pursuant to Buie

23A of the rules of Civil Procedure for the District Courts

of the United States. The rights here involved are of

common and general interest to the members of the class

represented by the Plaintiffs, namely, Negro citizens and

residents of the State of Maryland and of the United

States who have been segregated in the use of recreational

facilities in Sandy Point State Park and Beach and have

been denied use of recreational facilities equal to those

Complaint

20a

offered to white persons by the State of Maryland. The

members of the class are so numerous as to make it

impractical to bring them all before the Court, and for

this reason, Plaintiffs prosecute this action in and on

behalf of the class which they represent without specifically

making all members thereof individual Plaintiffs.

5. The Plaintiffs, Milton Lonesome, Marion J. Downs,

Alvin Graham, Beatrice Martin, and Bowen Jackson, are

citizens of the United States and are residents and domi-

ciliaries of the State of Maryland. They are over the age

of 21 and are taxpayers of the State of Maryland and of'

the United States. Minor Plaintiffs Karleen Downs,

Christine Jackson, and Lilly Mae Jackson are citizens of

the United States and residents and domiciliaries of the

State of Maryland; this action is brought in their behalf

by their parents and next of kin. All of the Plaintiffs are

classified as Negroes under the laws of the State of Mary

land.

6. Defendants, members of the Commission of Forests

and Parks of Maryland, Sidney D. Peverley, Bernard I.

Gonder, H. Lee Hoffman, J. Miles Lankford, and J. Wilson

Lord, are empowered under Article 39A, and Article 25,

Section 3 of the Annotated Code of Maryland to establish

and supervise recreational facilities, including bathing

beaches and bathhouse facilities for the benefit of the

citizens and residents of the State of Maryland. Defend

ant Joseph F. Kaylor, is Director of the Department of

Forests and Parks of Maryland and supervises the opera

tions of the Department under Article 39A, Section 2 of

the Annotated Code of Maryland. Defendant Joseph

Henderson is Superintendent of Sandy Point State Park

and Beach by appointment and under the supervision of

the Commission and Director. The immediate control and

Complaint

21a

operation of the facilities, subject to this suit, is in the

hands of the Superintendent of said facility.

7. All Defendants are being sued in their representa

tive and official capacities.

8. Pursuant to authority set forth in Article 39A of

the Annotated Code of Maryland, Defendants have estab

lished and are maintaining and operating bathing and

recreational facilities and advantages to citizens and resi

dents of the State of Maryland.

9. The Defendants herein are charged with the duty

of maintaining, operating and supervising Sandy Point

State Park and Beach as a part of their supervisory

control and authority. These Defendants have the exclu

sive power to promulgate and enforce rules and regulations

with respect to the use, availability and admission to Sandy

Point State Park and Beach.

10. On July 4,1952, Plaintiffs Milton Lonesome, Marion

J. Downs, Karleen Downs, Alvin Graham, Beatrice Martin,

Bowen Jackson, Christine Jackson, and Lilly Mae Jackson,

sought the use of these facilities and were denied by Joseph

P. Kaylor the use of the facilities at South Beach at Sandy

Point Beach and Park, solely because of their race and

color, and Joseph P. Kaylor directed them to use the East

Beach for colored persons, while at the same time white

persons entered and used all facilities at South Beach,

including roads, bathhouse, beach, concession, and picnic

grounds, without question. Plaintiffs protested that such

denial deprived them of their constitutional rights.

11. Plaintiffs were escorted to East Beach by Defend

ant Kaylor and refused to use said facilities because they

Complaint

22a

were physically unfit for use, and psychologically undesir

able, since segregated facilities could not afford them

complete, wholesome recreation.

12. (a) The inequality, physical and psychological as

referred to elsewhere herein, are more fully described in

Plaintiffs’ Exhibits A through I.

(b) Exhibit A is the affidavit of Dr. Roscoe Brown,

member of the faculty of New York University, Department

of Physical Education and Recreation, who made a com

parative study or survey on July 11,1952, of the facilities at

the East and South Beaches at Sandy Point State Park.

Exhibit B is the affidavit of Mrs. Juanita Jackson

Mitchell, member of the Executive Board of the Baltimore

Branch of the National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, who held a conference with officials of

the State Dexmrtment of Public Improvements on July

15, 1952, at 506 Park Avenue, Baltimore, Maryland.

Exhibit C is the affidavit of Mr. Bowen Jackson, Plain

tiff in this action, citing his reasons for his request to

this Court for the temporary restraining order.

Exhibit D is an official aerial photograph of the Sandy

Point State Beach and Park, made by the Maryland Air

Photo Service, Harbor Field, Baltimore 22, Maryland, for

the State Department of Public Improvements, which was

given to Mrs. Juanita Jackson Mitchell by Mr. Nathan L.

Smith, Director of the Department of Public Improve

ments at a conference held in his office at 506 Park Avenue,

on July 15, 1952. Mrs. Mitchell’s affidavit to this effect

is attached to said Exhibit D.

Exhibits E, P, G, H, and I, are photographs taken by

Irving Henry Phillips, 904 Whitmore Avenue, Baltimore,

Maryland, on the East and South Beach facilities on July

4, 1952.

Complaint

23a

13. Plaintiffs and those similarly situated and on whose

behalf this suit is brought, have suffered, are suffering,

and will suffer irreparable injury by the acts herein com

plained of. The rights which they seek to have enforced

are peculiarly enjoyable only during the summer months.

They have no plain, adequate, or complete remedy to

redrees the wrongs and illegal acts herein complained of

other than this suit for temporary restraining order, inter

locutory injunction, permanent injunction, and declaratory

judgment. Any other remedy to which Plaintiffs and those

similarly situated could be remitted would be attended

by such uncertainties as will deny substantial relief, will

involve multiplicity of suits, cause further irreparable

injury, vexation, and inconvenience to them.

W herefore, Plaintiffs pray:

1. That proper process issue and that this cause be

advanced upon the docket.

2. That the separate motion for temporary restrain

ing order be entertained at once and be granted.

3. That a preliminary or interlocutory injunction be

granted enjoining further denial to plaintiffs or any other

person similarly situated from using the facilities at South

Beach.

4. That the Court adjudge, decree, and declare the

rights and legal relations of the parties to the subject

matter here in controversy in order that such declaration

shall have the force and effect of a final order or decree.

5. That the Court enter a judgment and declare that

the policy, custom, usage and practice of the Defendants

in refusing to permit Negroes to use all the facilities at

Sandy Point State Park and Beach contravenes the

Complaint

24a

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

6. That the Court enter a judgment and declare that

the policy, custom, usage and practice of the Defendants

contravene the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States where the facilities set aside for

the use of Plaintiffs and those similarly situated at Sandy

Point State Park and Beach are physically inferior and

inflict psychological damage, making equal recreation

impossible.

7. That this Court issue a permanent injunction for

ever restraining the Defendants and each of them, their

lessees, agents and successors in office from denying to

Plaintiffs and other Negro residents of the State of Mary

land, the use and enjoyment of any beach or bathhouse

establishment, operated and maintained by the State of

Maryland, on account of race and color.

/s / L in wood G. K ogeb, Jr.,

Linwood G. Koger, Jr.,

1607 West North Avenue,

(Lafayette 1513),

Baltimore, Maryland,

Complaint

/ s / T ucker R . D earing ,

Tucker R. Dearing,

1235 North Caroline Street,

(Peabody 6651),

Baltimore, Maryland,

Attorneys for Complainants.

25a

The Answer of the Defendants herein, by Hall Ham

mond, Attorney General of the State of Maryland, and

Robert M. Thomas, Assistant Attorney General, their

counsel, to the Complaint filed against them herein respect

fully says:

(1) The Defendants are without knowledge or informa

tion sufficient to form a belief as to the truth to the allega

tions contained in paragraphs 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 of the Com

plaint.

(2) The Defendants admit the allegations contained in

paragraphs 6, 7, 8, and 9 of the Complaint.

(3) Answering paragraph 10 of the Complaint, the De

fendants admit that on July 4, 1952, the Defendant Joseph

P. Kaylor denied certain Negroes “ the use of the facilities

at South Beach at Sandy Point Beach and Park, solely

because of their race and color” and “ directed them to use

the East Beach for colored persons, while at the same time

white persons entered and used all facilities at South

Beach, including roads, bathhouse, beach, concession, and

picnic grounds, without question” , but Defendants are

without knowledge or information sufficient to form a be

lief as to the truth of the allegation contained in said para

graph 10 of the Complaint that the Negroes so denied the

use of South Beach on July 4, 1952, were the plaintiffs

listed in said paragraph 10 and that said Plaintiffs pro

tested that the action of the Defendant Kaylor deprived

them of their constitutional rights. Further answering

said paragraph 10, the Defendants allege that the afore

mentioned action of the Defendant Kaylor was taken pur

suant to the policy and practice of the Defendants to

Answer

26a

reserve South Beach at Sandy Point State Park for the

exclusive use of white persons and to reserve East Beach

at said Park for the exclusive use of Negroes, and pursuant

to the policy and practice of the Defendants to do all

within their power to keep the two said Beaches and the

facilities thereon equal in size, in proportion to the white

and Negro population of the State of Maryland, and equal

in quality.

(4) Answering paragraph 11 of the Complaint, the De

fendants admit that on July 4, 1952, the Defendant Kaylor

directed certain Negroes to East Beach, but are without

knowledge or information sufficient to form a belief as to

the truth of the allegation in said paragraph 11 that the

said Negroes “ refused to use said facilities because they

are physically unfit for use, and psychologically unde

sirable” .

(5) Answering paragraph 12 of the Complaint, the

Defendants deny generally the inequality alleged in para

graph 12 of the Complaint and in Plaintiffs’ Exhibits A

through I attached to said Complaint, but the Defendants

admit that whereas East Beach and South Beach were

originally natural beaches equal in quality, unusually heavy

storms in the Spring of 1952 and other natural causes

beyond the control of the Defendants have caused East

Beach to erode, with the result that some sand has been

washed away and parts of the beach have become muddy.

Further answering said paragraph 12 and Plaintiffs’ Ex

hibits thereto, the Defendants allege that engineers have

already studied the erosion problem at East Beach and

have devised plans for the correction thereof. The De

fendants have submitted their budget requests to the State

Planning Commission, giving the highest priority to the

Answer

27a

funds required to correct the aforementioned deficiencies

at East Beach. The Defendants further allege that it may

be possible to correct the erosion problem at East Beach

prior to the official reopening of Sandy Point State Park

in the Summer of 1953 and that the Defendants will do all

within their power to accomplish that result. The defend

ants further allege in answer to said paragraph 12 of the

Complaint that the photographs contained in Plaintiffs’

Exhibits D, E, F, G, H, and I, or copies thereof, have not

been served on any of the Defendants and that, therefore,

the Defendants are without knowledge or information suffi

cient to form a belief as to whether said photographs ac

curately portray the conditions at Sandy Point, State Park,

and on the various beaches thereof, at the times in question

in this proceeding.

(6) Answering paragraph 13 of the Complaint, the

Defendants deny the allegations contained in said para

graph. Further answering said paragraph 13, the defend

ants allege that Sandy Point State Park was officially

closed for the season on September 14, 1952, and will not

be officially reopened until a date yet to be determined in

May, June or July of 1953. Throughout this entire period

in which the said Park has been and will be officially closed,

the public has been and will be permitted to use the Park

grounds, but no bathhouses or other facilities on either

East Beach or South Beach have been or will be available

for the use of the public, and no lifeguards have been or

will be stationed on East Beach or South Beach. Due to

the limited use of the said Park during the closed season

under the circumstances outlined above, the Defendants do

not deem it necessary or practical to enforce the policy of

separate and equal facilities throughout said closed season

and have not attempted and will not attempt to enforce

Answer

28a

segregation of the Plaintiffs or others in the same class

as the Plaintiffs in the use of said Park throughout the

period in which it has been and will he officially closed.

W herefore, having fully answered the Complaint filed

against them herein, the Defendants pray to be dismissed

hence with their reasonable costs.

A nd, as in duty bound, etc.

/ s / H all Hammond (per R. M. T.),

Attorney General.

/ s / R obert M. T homas,

Asst. Attorney General,

Attorneys for Defendants,

1201 Mathieson Building,

Baltimore 2, Maryland.

Answer

29a

Baltimore, Maryland, July 9, 1953

Opin io n (oral)

Opinion of Court Re Vacating Preliminary

Injunction, etc.

Chesnut, J . :

Gentlemen, by the very nature of the ease, it calls for a

prompt decision. It is well to go back a bit and see when

this case began, and what is the object of the suit.

The case was instituted sometime late last summer, in

August, 1952, and the points made in the complaint then

filed by the plaintiffs were, in the first place, that the State

Board of Forests and Parks had no authority constitution

ally to require segregation of races, with regard to the

beaches at Sandy Point. The second and alternative con

tention was that the facilities for bathing at Sandy Point

were unequal. Now, as far as I can recall, there was no

application to advance the hearing on motion for restrain

ing order or preliminary injunction against the defendants

during that summer. It may very well be that because of

the time and the proximity to the close of the summer sea

son at Sandy Point made it hardly a practical thing to set

the case for an earlier hearing. At all events, the first

hearing that I can recall in the case now is that about the

first of May, I think, I was asked to assign a date for a

preliminary injunction hearing, and I fixed a date. In

due course, that came on to be heard. On the evidence

then presented I found that the facilities were unequal.

There was no argument, nor has there been up to the

present time, any discussion as to the constitutional ques

tion involved, but a question of fact as to whether the

facilities were equal.

Now, on the evidence that was presented on June 2nd,

at the hearing on the plaintiffs’ motion for preliminary

30a

injunction, I found, as a matter of fact, that the facilities

for white people and colored people, that is, with respect

to the South Beach for white people and East Beach for

colored people, were not equal, and it further appeared

from the evidence at that time that it was quite unlikely,

as the matters then stood, that there would he a substan

tial change in the situation for several months, or, I think,

as it was expressed, until the middle of the summer. So a

preliminary injunction was awarded to the plaintiffs.

There were two reasons why it seemed unlikely then

that there could be any equality brought about at the two

beaches. One was a very serious doubt as to whether the

State could get any funds which could be used for the

purpose of improving the East Beach. And, secondly,

even if the funds could at once be made available, it seemed

rather doubtful that the improvements would be made in

time to be of practical benefit to anybody. Of course, the

Court is not called upon to prophesy about facts that might

happen in the future.

On or about July 2nd, I received word that the defend

ants wished to move or had filed a motion to vacate the

injunction on the ground that the conditions had changed,

and that the facilities then existing were equal. In due

process, the plaintiffs were entitled to file their answer to

that paper, which apparently was filed on July 2nd, with

the hope on the part of the State to get the advantage of

the week-end of July 4th for the use of the beaches by the

people of the State. But, as the plaintiffs were entitled to

file their answer, they were justified in taking that time

before filing an answer. They filed their answer on July

6th, I think, or affidavit made, and I began the hearing on

the next day. Counsel for the plaintiffs said they were

not ready then, but I heard the State’s side of the evi

dence, postponed further consideration of it to give plain-

Opinion of Court Re Vacating Preliminary

Injunction, etc.

31a

tiffs ample opportunity to have an inspection made of the

beaches, as they desired, and produce such testimony as

they desired, and then it was understood on Tuesday,

when we had the hearing, that the final hearing on the

evidence, at least, would be made. Now, then, that morn

ing I learned, much to my surprise and astonishment

really, that the person whom the plaintiffs desired to pre

sent as an expert on the equality of the beaches had been

refused admittance to the premises yesterday afternoon,

at five o ’clock. He was restricted for some reason, not

being able to examine the South Beach, and he thought

the thing to do, in order to compare East Beach and South

Beach, was to decline to inspect the East Beach, although

the opportunity as to inspection of it was tendered him at

the time.

I heard the explanation made by representatives of the

State Board of Forests and Parks as to why this had

happened, the plaintiffs’ witness had not been given a free

opportunity to inspect everything he wanted, and I cer

tainly was not impressed with their reasons for it.

At all events, this morning the plaintiffs were not pre

pared to go on with the evidence. I think the defendants

made a primary error of judgment there in attempting to

limit freedom of inspection. Then, I think there was lack

of cooperation on the part of the plaintiffs in their refusal

to inspect East Beach, which was really the one more

particularly of importance here, because the testimony, as

I recall it, was that nothing had been done to the South

Beach at all. So I regretted the lack of cooperation in this

case between counsel, especially as the Court was doing

its best to cooperate with everybody in trying to get a

prompt hearing in the case. However, all that is more or

less water over the dam or under the bridge, and is of no

particular consequence, because I have heard all the evi

dence that both sides desired or were able to produce.

Opinion of Court Re Vacating Preliminary

Injunction, etc.

32a

In the first place, let me say, as to the constitutional

question that is involved, that has not been argued before

the Court at this time, and I rather gather that counsel

for the plaintiffs did not desire to argue it because a very

similar question is pending now in the Supreme Court of

the United States, and has been pending there for many

months. Upon the last session of the Supreme Court, it

ruled that that case should go over for further argument

on particular points generally, and in particular, until the

next term of court in the fall.

The existing constitutional law on the subject, though,

at the present time, is that segregation is the policy of the

State, and when it is adopted by the State, it is still consti

tutional provided facilities for the different races are sub

stantially equal. Therefore, the Court has nothing to do

at this time with the first point that is raised. In other

words, it does not call for any adjudication on my part.

A much narrower question, and the only question before

me, is whether the facilities for the different races at Sandy

Point Beaches are substantially equivalent. Now, I have

given some thought to that matter. In the first place, when

the hearing took place on June 2nd, there was no question

but that the East Beach was not equal to that of the South

Beach and, as I understand it, Mr. Parker, counsel for the

defendants, expressly concurred in that view as of that

time. The contention, however, on the other side at the

present time is that the facilities have been made equal.

Now, what are the essentials of a bathing beach? In

the first place, there is nobody I know of who contends

that a bathing beach along the Chesapeake Bay is at all

comparable in its quality or equal characteristics compar

able to many features of beaches such as Atlantic City,

Cape May, and elsewhere. Nature simply has not provided

Opinion of Court Re Vacating Preliminary

Injunction, etc.

33a

the type of bathing beach in the waters of the Chesapeake

Bay that it has for bathers on the Atlantic Seaboard in

the Middle States. The essentials of a beach, whether

Atlantic City or Ocean City or on the Chesapeake Bay, I

think are of three factors. One is the bathhouse, its sani

tation, its construction, its water supply, and general facili

ties for the convenience and comfort of the bathers. Sec

ondly, is the quality of the beach itself, that is to say, the

soil or sand of the beach from the bathhouse to the water.

Third, is the gradual increase in depth of the water as

you proceed into it. If you have a rapidly shelving beach,

it may be quite dangerous, especially for young children

and for not qualified swimmers. If you have water increas

ing in depth to such a slight degree that you have to wade

out a half mile before you undertake to swim, that is a

disadvantage.

Now, I think the question of whether the East Beach

is substantially so good as the South Beach must be deter

mined by those three factors, and as of the present time.

Now, what has happened? The injunction was issued

on June 4th. The State acting, I think, through the author

ity of the Board of Public Works, very promptly made a

substantial sum of money available for the improvement

of the East Beach. I think the evidence was that $36,000

had been appropriated for that purpose, or made available,

and a very competent contractor named Asher, who has a

very considerable experience in this special matter of pro

viding beaches along the Chesapeake Bay, was engaged to

improve the East Beach. Instead of taking two months or

more to do work which possibly could ordinarily not have

been expected to be done in that time, the evidence before

me shows that this contractor, a competent and experienced

man, knowing what to do because he had had similar work

to do in other places and had successfully done it, this

Opinion of Court Re Vacating Preliminary

Injunction, etc.

34a

contractor put on a special force of men and he went right

to work. And he did do a very thorough job there. As a

matter of fact, the State has incurred an expense not only

of $36,000, when the contract was let, but has actual ex

penditures of $66,000 for the work done solely on the East

Beach by the contractor.

What was the work done ? In the first place, there was

a proper objection made heretofore to the quality and

character of the land or soil or sand over which people had

to travel to go from the bathhouses to the water, and a

good deal of what has been referred to as root mat had

become imbedded with the sand and gravel. That was all

taken up, so far as the evidence shows. There is hardly

any dispute that that has not been done.

It was originally contemplated, according to the evi

dence, as I recall it, on Tuesday, that 18,000 tons of good

quality sand should be brought from another point miles

away by this contractor—Davidsonville I think he referred

to as the place where he got it—and that he had brought

in and placed on the East Beach about 30,000 tons of sand.

Now, then, I have seen samples of that sand which were

taken and exhibited here in Court. To my mind, it is

perfectly clear that as of the present time, the quality of

sand or the soil which is traversed from the bathhouses to

the water is superior on the East Beach to that on the

South Beach.

Now, as far as the bathhouses themselves are concerned,

there has never been any controversy, as I understand it,

as to the quality of the two being precisely the same. They

followed, as I understand it, the same specifications in

building them. The number of separate bath houses, I

believe, is smaller on the colored section than on the white,

because statistics here have shown there is a very much

smaller number of colored people who have availed them

Opinion of Court Re Vacating Preliminary

Injunction, etc.

35a

selves of the facilities. Possibly it is true that has been

due to the fact that heretofore they were not equal or

suitable, and they cannot be blamed for utilizing something

that is not agreeable. But unless and until there is a

demand for a larger number of bathhouses for the colored

people, I find from the evidence that the quality all around

there is certainly equal to, indeed is the same as that for

the white people. Of course, if more are needed, they will

have to be constructed hereafter by the State, if the quality

is to be maintained.

Now, then, when you come to the gradual increase in

the depth of water, and the sand under the water, and the

general comfort and pleasure of bathing, I find that at

least the greater weight of the evidence here by people

who I think are most qualified to speak, based on their

experience, as testified to, is that the approach into the

water at the East Beach is as good as that at the South

Beach.

I think that covers the three essentials of what consti

tutes really a bathing beach. There are some other things

here the plaintiffs rely on which I think are not really

material to the case.

In the first place, something is said about there being

a pond which is more attractive in the rear of the South

Beach than that, if there is any, at the East Beach. That

is not an essential of a bathing beach. That is simply one

of the features at Sandy Point Park as a whole, and it

has no particular relation to the bathing beaches. Then

it is suggested that there are more pleasant places to eat

a. luncheon under the trees on the South Beach than on the

East Beach. There, again, that is no essential point of a

bathing beach. So far as I can recall, I don’t remember

either at Cape May or Atlantic City—I have not been to

Ocean City recently—that there are any trees at all on the

Opinion of Court Re Vacating Preliminary

Injunction, etc.

36a

beach or right by the beach. Until you cross the boardwalk

at Atlantic City, I do not think you can find anything

green. What most people do, I believe, at beaches, accord

ing to what I have seen in illustrated weeklies, is that they

have tents out there and sit under them, or they bury

themselves in the sand and shade themselves or part of

themselves in that way to some extent. At all events, I

do not think picnic groves are an essential part of the

picture to determine whether the facilities at Sandy Point

are equal.

I think that practically covers the matter. My ultimate

finding, as a matter of fact, is that the facilities are in fact

equal, not only substantially equal, using the word with a

certain amount of leeway, but I think the State has done,

according to the evidence, a very excellent job there to

equalize the conditions.

I must add, however, not that it is a thing of impor

tance at the present time but a problem that will remain

that must be. taken into consideration.

At the first hearing back in June, I noted that the report

from the State Geologist was to the effect that the con

tinuity of desirable conditions on South Beach was a

matter of natural hazards or sources or conditions likely

to be more permanent than those of the East Beach, and

that until jetties were built out into the water, jetties or

groins, I think they are called, there would likely be from

time to time an erosion of the East Beach. The problem,

however, is not what may be the condition as the result of

a severe storm that may happen here within a week or

within six months, but what is the condition today. If

there is a storm which erodes the East Beach at any time

hereafter during the summer season, and it is not immedi

ately repaired or repaired as promptly as reasonable ex

pedition would permit by the Board of Forests and Parks

Opinion of Court Re Vacating Preliminary

Injunction, etc.

37a

then, of course, the plaintiffs are entitled to ask for a

reopening of the matter, with a probable restoration of the

injunction. But I think the matter of constructing these

groins or line of breakwaters to prevent erosion is some

thing that deals with the long-range problem of mainten

ance. It is quite possible that if these breakwaters are

not established during the summer, the ordinary high tides

of the fall or the more severe water conditions of the.

winter, may entirely change the situation there and require

a restoration of the injunction. It is quite probable that

before another summer season, there may be constitutional

law to be considered in connection with the whole problem.

Of course, as I say, the Court is not dealing with that matter

at this time-.

As I find that by the energies of the State and expendi

ture of State money for the express purpose of in good

faith creating equal facilities, that result has at the pres

ent time, some five weeks after the injunction was issued,

been accomplished, I think the defendants are entitled to

have a vacation of the injunction which heretofore was

passed in the case. And, of course, on the basis of it being

permissible legally, it is obviously desirable that the people

of the State of Maryland should have the benefit of this

more or less natural forest and park area which has been

acquired for them, and that they should not be closed with

respect to the particular summer activities of bathing,

when, as I find, the facilities there are equal.

Counsel can prepare and present to me, if they desire,

promptly this afternoon, the order vacating the injunction.

Opinion of Court Re Vacating Preliminary

Injunction, etc.

I certify that the foregoing is a true and correct tran

script of the opinion of the Court in the above-entitled case.

/ s / Ray F arrell,

Official Reporter.

38a

Motion for Judgment on Pleadings

Milton Lonesome, Marion J. Downs, Karleen Downs,

Minor, by Marion J. Downs, her mother and next of kin;

Alvin Graham, Beatrice Martin, Bowen Jackson, Christine

Jackson, Minor, by Bowen Jackson, her father and next

of kin; Lilly Mae Jackson, Minor, by Bowen Jackson, her

father and next of kin, plaintiffs herein, move the Court

to enter judgment on the pleadings filed in this case in

favor of the plaintiffs and against the defendants and

assign therefore the following reasons:

1. The complaint alleges a violation of plaintiffs’ con

stitutional rights in that defendants require racial segre

gation in the facilities which are the subject of this action.

2. The answer admits that defendants exclude plain

tiffs from these state-operated facilities to which they

sought admission solely because of their race.

3. Such racial segregation violates the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution.

/ s / Linwood G. R oger, Jr.,

Linwood G. Koger, Jr.,

1607 West North Avenue,

Baltimore, Maryland.

/ s / Tucker R. B earing,

Tucker R. Dearing,

716 North Gay Street,

Baltimore, Maryland,

/ s / Jack Greenberg,

Jack Greenberg

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York.

Attorneys for Plaintiffs.

39a

Answer to Plaintiffs’ Motion for Judgment

on Pleadings

Now come the Defendants in the above entitled case,

by Edward D. E. Rollins, Attorney General of Maryland,

and W. Giles Parker, Assistant Attorney General, their

attorneys, and, in answer to the Motion for Judgment on

Pleadings, says:

1. That the Defendants admit that the complaint alleges

a violation of Plaintiffs’ constitutional rights.

2. That Defendants deny that Plaintiffs are excluded

from the State-operated facilities, hut aver that Plaintiffs

and all others are admitted to Sandy Point State Park,

and that separate but equal facilities have been provided

in connection with bath houses and bathing beaches only.

3. That Defendants deny that any acts of theirs con

stitute a violation of the 14th Amendment to the United

States Constitution.

A nd, having answered the aforesaid Motion, Defend

ants pray that the same be dismissed with proper costs.

/ s / E dward D. E. Rollins,

Attorney General,

/ s / W. Giles Parker,

Assistant Attorney General,

Attorneys for Defendants.

40a

Stipulation

(Filed June 18, 1954)

It is stipulated and agreed by and between the parties

in this case that the separate facilities in question herein

are physically equal at this time.

/ s / L inw ood G. K oger, Jr.,

/ s / T u cker R. B earing ,

/ s / J ack Greenberg ,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs.

/ s / E dward D. E. Rollins,

/ s / W . Giles Parker,

Asst. Attorney General,

Attorneys for Defendants.

41a

— ---------------------------------- o - ----------------------------------

No. 6903

Robert M. Dawson, et al.,

vs.

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, et al.

No. 6904

M ilton L onesome, et al.,

vs.

R. Brooke Maxwell, et al.

—----------------------------o---------------------------- --

Excerpts From Transcript of Proceedings *

Tuesday, June 22, 1954.

# # *

[3] Mr. Parker: May it please the Court I would like

to make it clear that I am representing* the Department of

Forests and Parks of the State of Maryland, and as far as

I am concerned I am not going to argue the philosophy or

morality or wisdom or not of any separation of races with

respect to [4] education per se, but I am solely interested

in representing the State of Maryland before this Court

to make out its contention with respect to the Department

of Forests and Parks represented by a Commission, this

Commission which issues regulations such as it has in this

case, and also I mention the fact that at Sandy Point we

have these equal facilities, and at times other than the swim

ming time there is no segregation at all, hut we do have

* Mr. Parker represented defendants in Lonesome vs. Maxwell.

Mr. Harlan, see infra, p. 42a, represented defendants in Dawson

vs. Mayor.

42a

Excerpts From Transcript of Proceedings

these equal facilities down there and other facilities are

open to all, and there are no other segregated facilities that

I know of at other places in the State of Maryland in con

nection with recreation other than the beach and bathing-

facilities at Sandy Point, and at Sandy Point State Park,

as I say, only the bath houses and bathing beach are sepa

rated. The rest of the park is open to all and there is no

segregation of any kind in the winter, of course, throughout

the park, and as far as the other facilities are concerned,

fishing facilities, and so on, they are open to everyone.

The Court: And you say there are no segregated facili

ties in the field of public recreation in the State Forests or

Parks?

Mr. Parker: Yes. The other State Parks are operated

on a free-for-all basis, open to all, and at Sandy Point the

only place of any kind where the Department of State

Forests and Parks operates that is the bath houses and

[5] bathing beach.

Now, I think there is no dispute that there is that this

Department has felt that it is necessary to do this because

they might fear there might be some disorder or something

of that sort, but of course there is no statute requiring it,

and I don’t believe there is anything to prevent them from

requiring segregation other than in the public schools.

* * *

[18] The Court: Well, as I understood Mr. Parker, he

makes the point that there must be some proper Govern

mental objective, that the rule must be reasonable, a rea

sonable one in order to achieve the objective, and that there

must be actual equality.

Mr. Harlan: Yes.

The Court: Assuming these tests are controlling, what

is the Governmental objective which you seek to maintain

by segregation?

43a

Excerpts From Transcript of Proceedings

Mr. Harlan: I think the Governmental objective is to

preserve order, to prevent any fights or riots at the swim

ming pools, as where you have contact, physical contact,

physical sport in recreation, you have to do that, as they

have to be kept apart, if possible.

Now, in the Boyer case there was much trouble where

those people were ordered to leave and they sat down and

would not leave. Certainly it was the exercise of a Gov

ernmental function there, as was pointed out by Judge

Bond in the Durkee case.

Now, I agree, of course, that conditions have [19]

changed, that the situation has changed, and you have the

Brown case and Bolling cases with respect to the field of

education but to say that that applies or that there is

sociological or social damage in the field of public recrea

tion or on public beaches, I think that is going far afield,

which the Supreme Court has not done. With respect to

that the Court stated in the Bolling case:

“ Classifications based solely upon race must be

scrutinized with particular care, since they are con

trary to our traditions and hence constitutionally

suspect.”

It is to be noted how that is worded, that they are to

be looked at carefully, that they are to be scrutinized care

fully.

The Court: Well, you feel there has to be some public

necessity which would justify it.

Mr. Harlan: I think there must be segregation in this

field to prevent contact between the races. Certainly other

wise you would certainly hurt bathing from an attendance

standpoint. I think the basic question here is whether you

apply the Brown and Bolling cases to the field of recrea

tion or whether you reject the doctrine of Plessy entirely,

and we feel that the law was laid down in this Court by

Judge Chesnut in the Boyer case and the other cases that

were tried here.

44a

The motions for judgments on the pleadings in these

three cases raise a single legal question: Does segregation

of the races by the State of Maryland and the City of

Baltimore at public bathing beaches, bath houses and

swimming pools deny plaintiffs any rights protected by

the Fourteenth Amendment.

No. 5965

In this case, filed in August, 1952, plaintiffs, adult and

minor Negroes, brought suit against the Commissioners

of Forests and Parks of the State of Maryland and the

Superintendent of Sandy Point State Park and Beach, to

restrain defendants from operating the bath houses and

bathing facilities at Sandy Point State Park on a segre

gated basis. Plaintiffs alleged that the facilities afforded

Negroes were not equal to those afforded whites and that

they had been denied admission to the facilities reserved

for whites solely because of their race or color. Defend

ants answered, denying that the facilities were not sub

stantially equal.

On June 4, 1953, following a hearing on plaintiffs’ mo

tion for a preliminary injunction, Judge Chesnut entered