Jenkins v. Missouri Brief of Appellants Kalima Jenkins, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jenkins v. Missouri Brief of Appellants Kalima Jenkins, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1985. 170eb5bf-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/03ea8e38-e628-4a20-a80c-68ac3762d944/jenkins-v-missouri-brief-of-appellants-kalima-jenkins-et-al-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

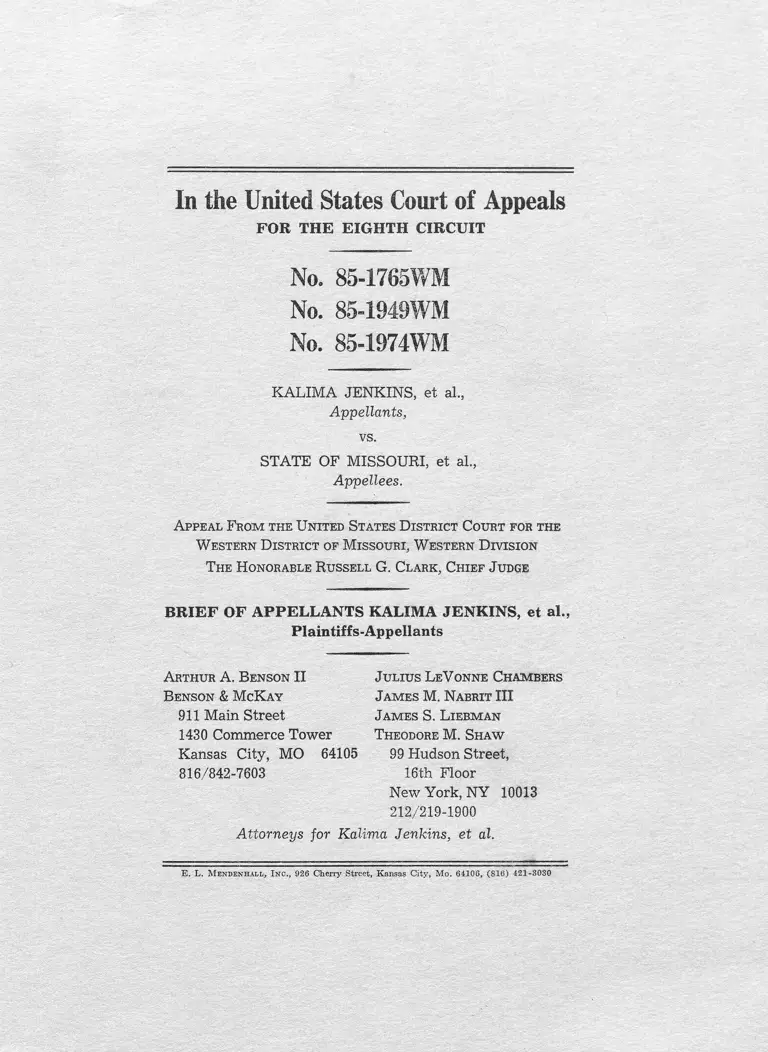

In the United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

No. 85-1765WM

No. 85-1949WM

No. 85-1974WM

KALIMA JENKINS, et al.,

Appellants,

vs,

STATE OF MISSOURI, et al.,

Appellees.

A ppeal F r o m the U nited States D istrict C o ur t for the

W estern D istrict of M issouri, W estern D ivision

T he H onorable R ussell G. C lar k, C hief Judge

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS KALIMA JENKINS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

A r t h u r A. B ens on II

B ens on & M cK a y

911 Main Street

1430 Commerce Tower

Kansas City, MO 64105

816/842-7603

Julius L eV o n n e C h a m b e r s

Ja m e s M. N abrit III

Ja m e s S. L i e b m a n

T heodore M, Sh a w

99 Hudson Street,

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

212/219-1900

Attorneys for Kalima Jenkins, et al.

E. L. Mendenhall, Inc., 926 Cherry Street, Kansas City, Mo. 64106, (816) 421-3030

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

No. 85—1765WM

No. 85-1949WM

No. 85-1974WM

KALIMA JENKINS, et. al.,

Appellants,

vs.

STATE OF MISSOURI, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District- Court

For the Western District, of Missouri, Western Division

The Honorable Russell G. Clark, Chief Judge

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS KALIMA JENKINS, et al.,

Plaintiff-Appellants

ARTHUR A. BENSON II

BENSON & McKAY

911 Main Street

1430 Commerce Tower

Kansas City, MO 64105

816/842-7603

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

JAMES M. NEBRITT III

JAMES S. LIEBMAN

THEODORE M. SHAW

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

212/219-1900

ATTORNEYS FOR KALIMA JENKINS, et al

SUMMARY AND REQUEST TOR ORAL ARGUMENT

Plaintiff-appellants (hereinafter plaintiffs) are 11 individual black

and white children living in the metropolitan Kansas City, Missouri area and a

class of black and white students in the Kansas City, Missouri School District

(KCM) represented by some of those individuals. Like most school children in

the area, plaintiffs attend segregated schools — blacks in all or predominantly

black schools in KCM, and whites in all or predominantly white schools in the

11 defendant, suburban school districts (SSDs). Prior to 1954, plaintiffs'

schools were segregated by laws providing for white children to be educated in

their home suburban canmunities but for black children to be educated on an

interdistrict-transfer basis in KCM. Plaintiffs' schools remain segregated

today, continuing the effects of the pre-1954 int.erdistrict dual school system,

which none of the culpable parties has ever acted to dismantle, and suffering

the additional effects of further intentionally and effectively segregative

actions with regard to schools and housing by the State, -SSDs, KCM and HUD.

The district, court, ordered some remedial-education relief for the black

plaintiffs living in KCM, but has (tone nothing to alleviate the segregated

enrollment and faculty conditions under which all of the plaintiffs, black and

white, attend school throughout the 12-district area. The court, absolved the

SSDs of any participation in a remedy and denied their school children, like

KCM's, any desegregation relief, based on erroneous legal conclusions that the

SSDs were guilty of no violation, even during the pre-1954 dual school era, and

that, their "autonomous" existence somehow bars the federal courts from

redressing the segregative effects on their children of other governmental

actors' unconstitutional behavior.

Every additional day spent by plaintiffs in their segregated schools

"may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone." Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 494 (1954). The issues in this case are

important.. Plaintiffs request. 60 minutes for oral argument.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Summary and Request For Oral Argument..................................... (i)

Table of Contents................................. (ijj

Table of Authorities................................ ...................... (V )

Short For Title of Cases................................................... (x)

Preliminary Statement...................................................... (xii)

Statement of the Issues.................................................. (xiii)

Statement of the Case..................... ................................ 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS.......................................................... 2

A. Missouri's Pre-1954 Interdistrict System of Locating

Dual Schools and Segregating Black Children........................ 2

Effects of Dual School System on Residential Patterns:

1. Depopulation of Blacks in Suburban Areas..................... II

Outside KCM

2. Increase in Population of Blacks in KCM...................... 14

3. All-White Subrogation Outside KCM............................ 15

B. Missouri's Metropolitan-wide Dual Housing System................... 16

1. State-enforced Racially Restrictive Covenants................. 17

2. The State's Inpact on FHA's Refusal to Insure................ 18

Mortgages on Homes by Racially Restrictive

Covenants

3. State-FHA Impact on the Dual Housing Market...... ............ 19

4. The Impact of the State/FHA-Fostered. Dual.................... 20

Housing Market on Persons Displaced by

Urban Renewal and Highway Construction

5. The Impact of the State/FHA-Fostered Dual.. .................. 23

Housing Market on HUD-Insured, -Assisted and

-Subsidized Single and Multiple-Family

Housing Programs

a. FHA After 1960........................................ . 23

(ii)

b. Section 235 Housing..................................... 24

c. Subsidized Housing and State Agencies.................... 26

d. Section 8................................................ 26

C. HAKC'S City-wide System of Segregated Public Housing............... 28

D. States and SSDs Post-1954 Segregative Action and.................... 31

Desegregative Inaction

1. H.B. 171...................................................... 32

2. Spainhower Commission......................................... 33

3. Milwaukee Plan......... ..................................... 33

4. Area Vocational Schools....................................... 33

E. Suburban District Failure to Desegregate............................ 34

F. KCM's Post-1954 Southeast Corridor Destabilization.................. 38

and Segregation

Summary of the Argument.................................................... 42

ARGUMENT

I. The Findings of the Court Below Establish Continuing................ 43

Interlocking Interdistrict Violations, Whose Cross-

District Nature and Metropolitan-wide Scope Require

Relief Encompassing the SSDs

A. Under Controlling Legal Principles, A ......................... 44

Constitutional Violation by or Affecting the

SSDs Requires Their Inclusion in an Interdistrict

Remedy

B. The District Court's Findings Establish Six..... ............... 49

Independent Bases for Interdistrict Relief

II. The District Court Denied Interdistrict Relief Based................ 58

on a Concatenation of Legal Error as to Interdistrict

Liability and Effect

A. Only by Six Times Abandoning the Controlling.................. 58

Legal Principles did the Court Absolve the SSDs

of Liability to Inclusion in an Interdistrict Remedy

(iii)

63B. The Court Below Applied an Improper Burden and..

Standard of Proof of "Significant Effects" in an

Improperly Piecemeal Fashion to an Improperly

Truncated Portion of the Relevant Evidence

III. The Court Erred in Absolving HUD of Constitutional................. 73

Violations Because Its Segregative Policies Were Not

Arbitrary and Capricious

IV. The District Court Erred by Failing to Afford any.................. 78

Desegregative Relief

CONCLUSION................................................................. 80

(IV)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Adams v. United States, 620 F.2d 1277 (8th Cir. 1977)

[Adams].......................... 5, 46, 47, 50, 58, 59, 61, 68, 69, 72

Banks v. Perk, 341 F.Supp. 1175 (N.D.Ohio 1972)...... ...................... 75

Barrow v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953)......................................17

Blackshear Residents Org. v. Housing Authority of Austin,........ ..........76

347 F.Supp. 1138 (W.D.Tex. 1971)

Board of Education v. St. Louis, 149 S.W.2d 878 (Mo. 1941)................. 7

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 494 (1954)...................... ...............75

Booker v. Special School Dist., 585 F.2d 347 (8th Cir. 1978)............... 68

Bose Corp. v. Consumers Union, ___ U.S. ____, 80 L.Ed.2a 502 (1984)........ 69

Bradley v. School Bd., 382 U.S. 103 (1965)................................. 69

Brewton v. Board of Educ., 233 S.W.2d 697 (Mo. 1950)....................... 2

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954)........................... passim

[Brown I]

Brown v. Board of Educ., 349 U.S. 753 (1955)............................... 38

[Brown II]

Clients' Council v. Pierce, 711 F.2d 1406 (8th Cir. 1983)............ ..75, 76

Columbus Board of Educ. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449 (1979) 46, 49, 61, 65, 68, 70

Continental Oil Co. v. Union Carbide, 370 U.S. 690 (1962).................. 70

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958)..........................................60

Dayton Board of Educ. v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406 (1977)................. 68, 69

[Dayton I]

Dayton Board of Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 528 (1979)

[Dayton II]......................... 49, 53, 60, 66, 68, 69, 73, 75, 78

Avans v. Buchanan, 582 F.2d 750 (3d Cir. 1978)............................. 67

Garrett v. City of Hamtramck, 503 F.2d 1236 (6th Cir. 1974)................ 75

Gautreaux v. Romney, 448 F.2d 731 (7th Cir. 1971).......................... 73

(v)

Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1977)

[Gautreaux]................. 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 51, 56, 61, 63, 65, 75

Graves v. Romney, 502 F.2d 1062 (8th Cir. 1974)............................ 77

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968)...................... 49, 75

Haney v. County Board of Educ., 410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969)

[Haney]............................. 46, 47, 49, 53, 60, 61, 62, 66, 69

Hart v. Community School Board, 383 F.Supp. 699 (E.D.N.Y. 1974)

[Hart].................. ............................ 48, 49, 58, 75, 79

Hoots v. Pennsylvania, 672 F.2d 1107 (3d Cir. 1982)

[Hoots]................................. 46, 47, 55, 61, 67, 68, 73, 74

United States v. Board of School Carm'rs, 573 F.2d 400 (7th Cir. 1978)

[Indianapolis I].................................................46, 57

United States v. Board of School Camm'rs, 637 F.2d 1101 (7th Cir. 1980)

[Indianapolis II].... ...............57, 58, 62, 67, 68, 69, 72, 74, 78

Jenkins v. State of Missouri, 593 F.Supp. 1485 (W.D.Mo. 1984).......... passim

Jones v. International Paper Co., 720 F.2d 496 (8th Cir. 1983)............. 44

Kelley v. Altheimer Pub. Sch. Dist., 378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967)...... 50, 61

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973)

[Keyes]......................................................69, 70, 75

femp v. Beasley, 389 F.2d 178 (8th Cir. 1968).............................. 69

Lee v. Lee County Bd. of Educ., 639 F.2d 1243 (5th Cir. 1981).............. 53

Lehew v. Brunmall, 15 S.W. 765 (Mo. 1891)................................ 2, 6

Liddell v. Board of Educ., 667 F.2d 645 (8th Cir. 1981)................ 49, 53

[Liddell III]

Liddell v. Board of Educ., 677 F.2d 626 (8th Cir. 1982)............ 47, 49, 54

[Liddell V]

Liddell v. Board of Educ., 731 F.2d 1294 (8th Cir. 1984).5, 47, 48, 52, 59, 68

[Liddell VII]

Newburg Area Council v. Board of Educ., 489 F.2d 925 (6th Cir. 1973)....... 69

[Louisville I]

Cunningham v. Grayson, 541 F.2d 538 (6th Cir. 1976)

[Louisville II

47, 53, 67

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971) 54

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) 45, 46, 47, 48, 51, 52,

[1Milliken]44,................... 53, 55, 56, 58, 60, 61, 62, 63, 65, 67

United States v. Missouri, 363 F.Supp. 739 (E.D.Mo. 1973).............. 53, 69

[Missouri I]

United States v. Missouri, 388 F.Supp. 1058 (E.D.Mo. 1975)........... ......47

[Missouri II]

United States v. Missouri, 515 F.2d 1365 (8th Cir. 1975)

[Missouri III].................. 46, 47, 49, 53, 59, 60, 61, 62, 66, 69

Morrilton School Dist, No. 32 v. United States, 606 F.2d 222

(8th Circuit 1979) [Morrilton]...44, 46, 47, 53, 58, 60, 61, 62, 67, 69

NAACP v. Harris, 567 F.Supp. 637 (D.C.Mass. 1983).......................... 75

Oliver v. Kalamazoo Bd. of Educ., 640 F.2d 782 (6th Cir. 1980)......... 47, 58

United States v. School Dist. of Omaha, 521 F.2d 530 (8th Cir. 1975)

[Omaha]........................................ .....48, 50, 54, 68, 71

Otero v. New York City Housing Authority, 484 F.2d 1122 (2d Cir. 1973)..... 75

Penick v. Columbus Board of Educ., 429 F.Supp. 229 (S.D.Ohio 1977), aff'd,

583 F .2d 787 (6th Cir. 1978), aff'd, 443 U.S. 449 (1979)............ 46

Reed v. Rhodes, 422 F.Supp. 708 (N.D.Ohio 1976), aff'd, 607 F.2d 714 (6th

Cir. 1979)............................... ....................... 47, 58

Richardson v. Belcher, 404 U.S. 78 (1972).................................. 73

Shannon v. HUD, 436 F.2d 809 (3d Cir. 1970)................................ 77

Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948)....... .................... 17, 20, 71, 73

State ex rel. Herman v. County Court, 277 S.w. 934 (Mo. 1925).............. 6

State ex rel. Hobby v. Dismin, 250 S.W.2d 137 (Mo. 1952).................... 2

State ex rel. Morehead v. Cartwright, 99 S.W. 48 (Mo.App. 1907)............ 8

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd.of Educ., 306 F.Supp. 1299 (W.D.N.C. 1969)58

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 431 F.2d 138 (4th Cir. 1970)...58

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971)

[Swann]................................. 10, 44, 45, 58, 65, 66, 67, 75

(vii)

Taylor v. Ouachita Parish School Board, 648 F.2d 959 (5th Cir. 1981)....... 48

Turner v. Warren County Bd. of Educ., 313 F.Supp. 380 (E.D.N.C. 1970)...... 53

United States v. Board of Educ., 306 F.Supp. 912 (N.D.I11. 1983).......... .58

United States v. Scotland Neck, 407 U.S. 484 (1972).................... 52, 61

United States v. Texas, 321 F.Supp. 1043 (E.D.Tex. 1970), aff'd, 447 F.2d...53

441 (5th Cir. 1971)

Weiss v. Leaon, 225 S.W.2d 127 (Mo. 1949).*................................ 17

Williams v. Kansas City, 104 F.Supp. 848 (W.D.Mo.), aff'd, 205 F.2d 47..... 3

8th Cir. 1952)

Evans v. Buchanan, 393 F.Supp. 428 (D.Del), aff'd, 423 U.S. 963 (1975)

[Wilmington I].................................. 47, 48, 52, 55, 57, 58

Evans v. Buchanan, 416 F.Supp. 328 (D.Del. 1976)....................... 47, 63

[Wilmington II]

Evans v. Buchanan, 555 F.2d 373 (3d Cir. 1977)............................. 47

[Wilmington III]

Evans v. Buchanan, 582 F.2d 750 (3d Cir. 1978)............................. 68

[Wilmington IV]

Wright v. Council of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972)............. .........49, 61

Ybarra v. City of San Jose, 503 F.2d 1041 (9th Cir. 1974).............. 47', 58

Statutes and Publications

Act of July 6, 1957, 1957 Mo. Laws 454..................................... 32

(H.B. 171, 1957)

Act of July 6, 1965, 1965 Mo. Laws 275..................................... 32

(Sec. 162.571, Mo.Rev.Stat.)

Missouri Housing Act of 1949........................................... 21, 28

(Sec. 99.320, Mo.Rev.Stat.)

42 U.S.C. § 1437 (Public Housing Program).............................. 28, 30

United States Housing Act of 1937

42 U.S.C. § 2000d,......................................................passim

U. S. Civil Rights Act of 1964 [Title VI]

(viii)

.24, 2612 U.3.C. { 1715z (1968)___

(Section 235 Program)

42 U.S.C. { 3601.............................................................

Fair Housing Act of 1968 [Title VIII]

42 U.S.C. { 1437f, The Housing and Community Development Act of 1974___26, 27

(Section 8 Program)

State Department of Education Bulletin...... ............................... 7

U. S. Const., amend. XIV............................................... passim

Note, Housing Discrimination as a Basis for Interdistrict School........... 58

Desegregation Relief, 93 Yale L.J. 340 (1983)

Mrydal, An American Dilemma.................................................12

Savage, The Legal Provisions for Negro Schools in Missouri, 16 Journal of... 6

Negro History 309 (1931)

dx)

[Adams]

[Brcwn I]

[Brcwn II]

[Dayton I]

[Dayton II]

[Gautreaux]

[Haney]

[Hart.]

[Hoots]

[Indianapolis]

[Indianapolis II]

[Keyes]

[Liddell III]

[Liddell V]

[Liddell VII]

[Louisville I]

[Louisville II]

[Milliken]

[Missouri I]

[Missouri II]

[Missouri III]

[Morrilton]

SHORT FORM TITLE OF THE CASE

Adams v. United States, 620 F.2d 1277 (8t.h Cir. 1977)

Brcwn v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

Brcwn v. Board of Educ., 349 U.S. 753 (1955)

Dayton Board of Educ. v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406 (1977)

Dayton Board of Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 528 (1979)

Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1977)

Haney v. County Board of Educ., 410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969)

Hart. v. Community School Board, 383 F.Suoo. 699 (E.D.N.v.

1974)

Hoots v. Pennsylvania, 672 F.2d 1107 (3d Cir. 1982)

United States v. Board of School Ccmm'rs, 573 F.2d 400 (7t.h

Cir. 1978)

United States v. Board of School Conm'rs, 637 F.2d 1101

(7th Cir. 1980)

Keyes v. School Dist- No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973)

Liddell v. 3oard of Educ., 667 F.2d 645 (8th Cir. 1981)

Liddell v. Board of Educ., 677 F.2d 626 (8t.h Cir. 1982)

Liddell v. Beard of Educ., 731 F.2d 1294 (3th Cir. 1984)

Newburg Area Council v. Board of Educ., 489 F.2d 925 (6th Cir

1973)

Cunningham v. Grayson, 541 F.2d 538 (6th Cir. 1976)

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974)

United States v. Missouri, 363 F.Supp. 739 (E.D.Mo. 1973)

United States v. Missouri, 388 F.Supp. 1058 (E.D.Mo. 1975)

United States v. Missouri, 515 F.2d 1365 (8t.h Cir. 1975)

Morrilton School Dist. No. 32 v. United States, 606 F.2d 222

8th Cir. 1979)

(x)

[Omaha] United States v. School Dist. of Omaha, 521 F.2d 530 (8th Cir

1975) ------

[Swann] Swann v. Chariotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1

(1971)

[Wilmington I] Evans v. Buchanan, 393

963 (1975)

[Wilmington II] Evans v. Buchanan, 416

[Wilmington III] Evans v. Buchanan, 555

[Wilmington IV] Evans v. Buchanan, 582

F.Supp. 428 (D.Del), aff'd, 423 U.S.

F.Supp. 328 (D.Del. 1976)

F.2d 373 (3d Cir. 1977)

F.2d 750 (3d Cir. 1978)

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

1. Chief Judge Russell G. Clark, United States District. Court, for the

Western District, of Missouri, Western Division, rendered the decisions appealed

from on January 24, 1984 (oral order, unreport.ed), April 2, 1984 (oral order,

unreported), June 5, 1984 (unreport.ed); September 17, 1984 (593 F.Supp. 143.5);

January 25, 1985 (unreport.ed); and June 14, 1985 (publication pending).

2. Plaintiffs seek to redress the deprivation, under color of state

law, of rights secured by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitu

tion of the United States, 42 U.S.C. §1983, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000d, et seq., and Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act. of

1968, 42 U.S.C. §3601, et seq. Because this action arises under the Constitu

tion and laws of the United States and 28 U.S.C. §1343, jurisdiction of the

District. Court, was based on 28 U.S.C. §1331.

3. Pursuant, to plaintiffs-appellants' timely notice of appeal dated

June 14, 1985, the jurisdiction .of this Court, is invoked under 28 U.S.C. §1291.

(xii)

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

!• Whether the District Court erred in absolving the suburban school

districts of responsibility for participating in Missouri's pre-1954

interdistrict system of dual schools and of any duty to take part in remedying

the effects on their children of that violation and of subsequent violations by

the Kansas City District and housing officials.

Milliken v. Bradley,

418 U.S. 717 (1974)

Morrilton School District No. 32 v. United States,

606 F.2d 222 (8th Cir. 1979) (en banc)

United States v. Missouri,

515 F.2d 1365 (8th Cir. 1975)

Evans v. Buchanan,

393 F.Supp. 428 (D. Del. 1975), aff'd, 423 U.S. 963 (1976)

2. Whether the District Court erred in requiring plaintiffs to over

come a "no continuing effects" presumption arising solely because of the passage

of time, and in excluding most, then disaggregating the rest of plaintiffs'

extensive evidence of continuing effects.

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberq Board of Education,

402 U. S. 1 (1971)

Morrilton v. School District No. 32 v. United States,

606 F.2d 222 (8th Cir. 1979) (en banc)

(xiii)

United States v. Board of School Commissioners,

637 F.2d 1101 (7th Cir. 1980)

Penick v. Columbus Board of Education,

583 F.2d 787 (6th Cir. 1970), aff’d, 443 U.S. 449 (1979)

3. Whether the District Court erred in applying an "arbitrary and

capricious" standard to HUD's conduct in explicitly mandating and knowingly

funding segregated housing in the Kansas City area.

Bolling v. Sharpe,

347 U.S. 497 (1954)

Clients Council v. Pierce,

711 F .2d 1406 (8th Cir. 1983)

Gautreaux v. Rcroney, 448 F.2d 731 (7th Cir. 1971)

4. ' Whether the District Court erred in failing to afford the victims

of the segregation it did find any desegregation relief at all and particularly

in failing to adopt plaintiffs' modestly priced, essentially voluntary housing

remedy.

Adams v. United States,

620 F.2d 1277 (8th Cir. 1980) (en banc)

Hart v. Conmunity School Board,

383 F.Supp. 699 (E.D.N.Y. 1974), aff'd, 512 F.2d 37 (2d Cir. 1975)

(xiv)

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The 11 plaintiff black and white school children live in the Kansas

City, Missouri metropolitan area. 1 The City of Kansas City, Missouri lies at

the center of that area and encompasses all or parts of 1.3 school districts

lying in 3 counties (Jackson, Clay and Platte) including 10 of the deferdant

school districts. Like KCM, 5 of the SSDs (CE, GV, HM, NK, RT) are either

entirely within or surrounded on at least 3 sides by the City. 2 School district-

lines in the metropolitan area do not. correspond to irunicipal boundaries or to

other geopolitical and commercial divisions. T10812-5.

The 12 defendant districts enroll 121,287 children, of vdiom 28,381

(24%) are black. Eighty-seven percent of the black students in the area attend

KCM while 89% of the white students attend one of the SSDs. KCM's student body

is 68% black; together, the SSDs are 5% black. 2

Plaintiffs seek to dismantle the segregation of school districts in the

metropolitan area caused toy defendants’ intentionally discriminatory acts.

2Six reside in the defendant Kansas City, Missouri School District. (KCM), 5 in

the defendant, suburban school districts (SSDs) — Blue Springs (BS), Center

(CE), Fort. Osage (FO), Grandview (GV), Hickman Mills (HM), Lee's Summit. (LS),

Independence (IN), Liberty (LI), North Kansas City (NK), Park Hill (PH) and

Raytown (RT). The State of Missouri and the United States Department of Housing

and Urban Development (HUD) are also defendant-appellees.

-X9, 36. Record citations take the following form: trial transcript (T);

exhibits (X); depositions ([ deponent.] D); Addendum (A). The district court.'s

published fact-findings are cited as "593 F.Supp. at." The court.'s other opi

nions are cited by their date and page number. Frequently cited cases are

referred to as indicated in the Table of Authorities.

2X53G. The 12 districts employ 7,071 teachers, 181 counselors and 389 admi

nistrators, of whom 16%, 12% and 24%, respectively are minority. KCM employs

approximately 96% of the area's minority teachers, 100% of the minority coun

selors, and 99.5% of the minority administrators. The teaching staff in KCM is

53% minority; in the SSDs, 1% minority. X721G, 3757 (p. 59-60).

1

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. Missouri's Pre-1954 Int.erdist.rict. System of Locat-ing Dual Schools

arid Segregating Black Children. —

Prior to 1954, students and teachers in Missouri were segregated by

law. "Each school district, in Missouri participated in this dual system before

it was declared unconstitutional." 593 F.Supp. at 1490; see Adams, 620 F.2d at

1290.4

Missouri superimposed dual schools on one of the roost intensely

fragmented systems of school district, organization in the nation. During most,

of the pre-1954 period, Missouri had the second or third largest, number of

4Bet.ween 1865 and 1976, 4 successive state constitutions provided "separate"

schools. While requiring that educational "funds [be] apportioned...without

regard to color," the 1865 Constitution provided that "[s]eparate schools may be

established for children of African descent.." Mo. Const. 1865, art.. 9, §2; see

also 1865 Mo. Laws 177. See X116, 116A-B, 117 (collecting laws and decisions

re: segregation). When the provisions' permissive language led Missouri's

Public School Superintendent to conclude in 1873 that, there would be "no right

of ejectment." if "two or three dark faces... slipped into" a white school (X208),

the State prorptly revised the constitution, making separate schools mandatory

and deleting the equal-funding provision. Mo. Const. 1875, art.. 11 §3, retained

Mo. Const. 1919, art. 11 §3, revised and retained, Mo. Const. 1945, art.. 9

§l(a), 3(c).

Lest, there be doubt: in 1889, the Missouri Legislature made .it. a criminal

offense for "any colored child to attend a white [public] school" (1889 Mo. Laws

226), extending the bar to private schools in 1909 (1909 Mo. Laws 770, 790,

820); in 1891, the Missouri Supreme Court, upheld the constitutionality of these

provisions, Lehew v. Brummell, 15 S.W. 765 (Mo. 1891); in 1910, the Attorney

General threatened to prosecute school officials operating integrated schools

(X178, T4225, 14813); in 1948, the State Board of Education invoked its

"inherent, authority" t.o withdraw funding frcm a school district, violating the

State's segregation provisions (X2222-5); and between 1944 and 1955, Missouri's

citizens and officials reaffirmed their canmitment to statewide segregation 5

times, rejecting proposals to mandate integration or allow it at. local option.

T5838; X2234; State ex rel. Hobby v. Dismin, 250 S.W.2d 137, 141 (Mo. 1952);

State ex rsl. Brewton v. Board of Education, 233 S.W.2d 697 (Mo. 1950). As

lat.e as 1965 (see 1965 Mo. Laws 306, amending, 1921 Mo. Laws 86), Missouri law

also required separate teacher-training (1901 Mo. Laws 249), higher education

(1929 Mo. Laws 1961), industrial and agricultural schools (1891 Mo. Laws 22,

33; 1929 Laws 386), school inspectors (1921 Mo. laws 611-5), juvenile homes

(1923 Mo. Laws 128), mental institutions (Mo.Rev.Stat.. §202.620 (1949)), and

censuses of "white and colored" children (Mo.Rev.Stat.. §164-030 (1949)).

Outside the area of education, Missouri lav/ until 1959 mandated separate

- 2 -

school districts in the nation5 — the vast majority of them with fewer than 50

children, black or white, spread over 12 grades.*5 The 3—county area surrounding

Kansas City was typical in this regard.5”

lavatories in certain industries (1915 Mo. Laws 332, repealed, 1959 Mo.

Laws, S.B. No. 188, §A); until 1969, "all marriages of white persons with

negroes" and, subsequently, "mongolians" were void and illegal (Mo.Rev.Stat.

§563.240 (1959), repealed 1969 Mo. Laws 545); and Missouri law still includes a

provision prohibiting interracial adoption (Mo.Rev.Stat. §453.130 (1969)). These

laws were augmented by Kansas City ordinances requiring separate hospitals (1941

Admin. Code, art.. VII, §36) and vital statistics collection (1946 R.O. §23-42),

and by local "custom and usage" dictating that public parks and swimming pools

be segregated. Williams.v. Kansas City, 104 F.Supp. 848 (W.D.Mo.), aff'd, 205

F.2d 47 (8th Cir. 1952); X120. In 1914, the Kansas City Council made it ille

gal to establish any "school. .. for... persons of African descent." within l/j mile

of a school for "persons not. of African descent." in order to avoid attracting

black residents to white neighborhoods. X124-A. And throughout, the 1920-55

period, the City Planning Department divided the city into "white" and "colored

districts" for purposes of zoning and locating schools, parks, recreation areas,

streets and highways. By consistently zoning black residential and surrounding

areas except immediately to the south and east of the core area industrial, city

planners assured that black neighborhoods would remain unattractive to whites

and would expand only south and east.. X282-B, 288-9, 306-7; T10870-901, 11043-6,

11247-8.

Law enforcement or lack of it. also operated in a segregating fashion in the

area: (1) At the turn of the century, vhit.es burned several black homes and

businesses in BS, causing its black population to leave the town. Local police

officers subsequently escorted blacks out. of BS whenever they ventured in, and

no blacks moved back to BS until the 1970s. T2267, X53G. See also T5071

(police in NK and RT followed like practices until the 1950s). (2) The Clay

County Prosecutor's refusal to investigate a 1925 lynching because "justice has

been done" caused "many...negroes who lived in and near Excelsior Springs volun

tarily to flee to Kansas City, believing they would be safe there." X99A, T499.

(3) Pre-Brcwn, Kansas City police failed to assist, blacks whose homes were

bombed when they moved into all-white neighborhoods (T14833), and the department,

segregated its force until 1959 (T5068-9). (4) Until the mid-1960s, the Jackson

County Court, and KCM jointly ran 4 explicitly segregated juvenile homes located

in FO, IN and LS, all of which received children cn a countywide basis. (6/5/85

Opn at. 21-2; X84, 222A).

-*T4132-4, X2322. Missouri had well over 10,000 school districts in 1900, 8326

as late as 1948. X212.

®In 1924, 86% of Missouri's 9000 districts had fewer than 60 children, 71%

fewer than 40, and 41% fewer than 25. In 1928, 30% of Missouri's school

teachers taught, in 1-rocm school districts (compared to 10% in Texas, 8% in

North Carolina and 7% in Georgia); and in 1945, over 5300 districts in the state

(about 65%) had fewer than 15 students. X210, 212, 507, 2322.

7'Throughout the 1900-50 period, there were over 60 school districts in Plat.t.e

- 3 -

Missouri imposed it.s segregation and fragmented-organization systems

on a widely dispersed black population. Between 1382 and 1923, over half of

Missouri's school-aged children lived in 93 counties with fewer than 1000 black

children distributed among anywhere from 60 to 100 school districts, and in sub

sequent years state documents reported tens of thousands of black school

children "scattered" throughout Missouri's "smaller cities...villages" and

"rural areas." X208, 210, 184 (1929), 184A (1943). Here, too, the 3-county area

was typical.^ Indeed, as of 1900, blacks made up about the same proportion of

school children enumerated in suburban Clay, Platte and Jackson Counties (7%) as

in KCM itself (9%) and accounted for 20% of the black children in the area. X51,

53E.

The consequence of mandating dual schools in thousands of 15-, 25-,

and 50-children districts among which half of Missouri's black children were

distributed was that those districts reserved the single schoolroom they could

afford for whites. As the 1924 Annual State School Report (Rep.) acknowledged,

"the isolation of colored children.. wonder the dual .system of education

[creates] one of the most perplexing problems in school administration" — how

to provide for black children "without taking a larger amount" of available

County (today there are 5),70 in Clay County and just under 100 in Jackson

County, many with fewer than 20 and even 10 students. X49-50C, 55B-E, 140,

150-3; T4203. Missouri officials repeatedly acknowledged that consolidated

districts would equalize and increase the educational opportunities of chil

dren and insure better learning (X207, 210, 212, 213, 507), but took no action

to require reorganization measures until just before Brown. See 1948 Mo. Laws

(S.B. 307). When legislatively mandated consolidation procedures took effect in

the decade surrounding Brown, however, the number of school districts in the

state dropped by over 5000 (compared to a reduction of 96 between 1930 and 1940)

and decreased by 30 and 92%, respectively, in Jackson and Platte Counties. X507,

(p.38) Herndon D90-1.

®As of 1900, all 25 townships in the area reported black populations, and in

1910, nearly all of the scores of "enumeration districts" into which the Census

Bureau divided Clay and Jackson County outside Kansas City enumerated blacks.

X37B-C, 43A-C; T3403-20. Approximately 60 distinct black settlements in the

3-county area outside KCM before Brown were situated in 55 different school

- 4 -

funds "than would be right." from "the larger group. "9

Rejecting proposals to solve its "perplexing problem" through integra

tion (supra n.4), Missouri chose instead to allow districts to forego black

schools and educate their black children on an interdistrict basis.^ Between

1866 and 1929, state law exempted school districts from providing schools for

districts” (current school district, in parentheses): Arley, Burlington (NK),

Carrol (LI), Excelsior Springs, Excelsior Springs Junctin, Faubion (NK), Harlem,

Holt, Kearney, Lawson, Liberty (LI), Martin, Mecca, Missouri City, Mos’cy (LI),

Moscow, Nashua (NK), Nebo, North Kansas City (NK), Prather Hill (NK), Randolph

(NK), Rocky Point., Smithville, White Oak (NK) in Clay County; Atherton (FO),

Blue Springs (BS), Buckner (FO), Courtney (FO), Elm Grove (FO), Fairviaw (BS),

Grandview (GVj, Greenwood (LS), Hazel Grove (LS), Hickman Mills (HM),

Independence (IN), Lee's Summit (LS), Lobb (FO/BS), Longview Farm (LS), Mason

(LS), Oakland (LS), Oldham (IN), Owen (FO), Peacedale (FO), Pitcher (KCM),

Pleasant- Valley (KCM), Prairie Dale (FO), Raytcwn (RT), Reber (FO), Rock Creek

(KCM), Sibley (FO), Spring Branch (IN), Staple (IN), Sunnyvale (BS), Union (FO),

Williams (BS), and Wright (LS) in Jackson County outside Kansas City; and

Parkville (PH), Plat.t.e City, Rocky Point, Valley Forest, Waldron and Weston in

Platte County. T485-6, 899-900, 919, 949, 955, 1326, 2265-7; X37A, 38, 49,

136-8, 226, 1784 (HM), 1830, 1834-40 (RT); Fickle D39.

Fragmentary school records establish that predecessors of all but 1 of the

SSDs had black resident children prior to Brown, a number (e.g., Liberty and

Mosby (LI), Owen and Union (FO), Staple (IN), Big Shoal (NK) and Platte City)

having black proportions as high as 15 to over 43% in given years. X49, 49B,

1784. CE is the only SSD in which the meager school records available do not.

unequivocally reveal black children prior to 1954. But cf. X43C, 50B, 54A;

T5888-92 (1900-40 census data revealing anywhere from scores t.o hundreds of

blacks living in enumeration districts and townships which overlap CE) . In view

of X49 and 1784, the court's findings with regard to GV and HM (6/4/84 Opn at.

51, 55) — adopted verbatim from findings preposed by those districts (infra

n.86) — are plainly wrong.

9x210 (p.195). "Although the percentage of negro children in the state is

rather small (about 5V2%)/ the problem of providing an effective education

program for them [is] difficult [because] the state Constitution provides that

separate schools be established. In states in which the proportion of negro

children is large, the maintenance of separate schools for the two races pre

sents no great practical difficulties. But in a...state such as Missouri this

provision.. .ccsrplicat.es the problem of providing adequate school facilities at a

reasonable cost." X210 (1929 Rep. at. 123). Accord, e.g., X180 (1867 Rep. at

191), 208 (1873 Rep. at. 44-5) (1384 Rep. at. 9); 210 (1922 Rep. at. 31), 211

(1931-2 Rep.), 183 (p. 21), 184A (1945).

-̂ 9593 F.Supp. at. 1490; see Liddell VII, 731 F.2d at 1305-6; Adams, 620 F.2d at.

1280-1, 1294 n. 27. Missouri thus added another aspect, of "dualism" t.o its

system, "operat.[ing] an intradistrict system for white kids [while] send[ing]

the black kids out of the district.." T4204-5. When black parents complained

- 5 -

black children whose enumeration fell below 15 and required then to

"discontinue" black schools whenever black "average daily attendance" fell below

8 ;1 1 and in 1929, the legislature gave "any school district" in the state, no

matter what its black enumeration, the qption to forego schools for blacks.

1929 Mo. Laws 382.

From the late 19th Century on Missouri law permitted districts not

required to provide schools for blacks to educate their black children on an

interdistrict- las is; but it was not until 9 years before Brown that state law

actually required districts to do so and to reimburse black children for the

full cost of their tuition and transportation elsewhere: (1) Missouri law did

not. give black children denied schools in their own districts even the

"privilege" of attending elsewhere until 1883 (corrpare e.g., 1874 Mo. Laws

163-4, with 1883 Mo. Laws 187), and when it did, it limited their attendance to

elementary schools (if there was cne; often there was not.) in the same

"township" or "county" until, respectively, 1887 and 1945 (compare 1945 Mo.

Laws 1700, with 1887 Mo. Laws 270, 1883 Mo. Laws 87); (2) it did not actually

require local boards to make interdistrict arrangements for elementary students

and to pay their tuition and part- of their transportation until 19 2 9 ,12 dig not.

extend those requirements to black high school students nor provide for state

about the hardships their children bore in transferring out of their hame

districts away frcm the local schools for white children, the Missouri Supreme

Court- conceded the inconvenience but found no "substantial" inequality. Lehew

v. Brumroell, 15 S.W. 765 (Mo. 1891).

Hl865 Mo. Laws 177; 1869 Mo. Laws 86-7; 1870 Mo. Laws, 149; 1887 Mo. Laws 264;

1893 Mo. Laws 247; 1909 Mo. Laws 790-91; Savage, The Legal Provisions for

Negro Schools in Missouri, 16 J. Negro Hist.. 309, 318 (1931) (school closure

"law keeps...five or six thousand Negroes out. of school each year").

■^Compare, e.g,, 1883 Mo. Laws 187 with 1929 Mo. Laws 382-33. See State ex rel.

Herman v. County Court., 277 S.W. 934 (Mo. 1925) (black children to have no stand

ing to sue to require their home district, to pay tuition in another district.).

- 6 —

reimbursement, of any portion of the local dist.rict.s' costs until 1931, and its

chief state school officer exempted local boards from conplying with the 1929

and 1931 provisions until late 1933 (1931 Mo. Laws 241, as interpreted in X135

(p. 21)); and (3) it did not withdraw either the 1929 Act's $3/month limit on

transportation costs the local districts were required to reimburse or the 1929

and 1931 Acts' limitation cn tuition/transportation payments to intraccunt.y

transfers until 194 5.13

Analyzing these laws in 1923, State Negro School Inspector Young noted

that Missouri was adequately providing for cnly the "50% of her Negro popula

tion" residing "in cities and a few other dist.rict.s" and concluded that so few

black children were in school because State law did not. "mak[e] it mandatory

upon school officials to provide schools, or instruction, for their Negro

children or pay transportation charges for these children to attend other

schools:"

In some districts there are not enough Negro children of

school age to have a free public school under the law. .. .

Hundreds, if not. thousands, of Negro children are denied free

public education through the operation of this law, which

literally "pockets" them educationally.... In other school

districts there are not enough Negro children to justify the

expense of organizing a high school, even if the officials

were willing, [so] they are marocned as regards public high

school education. The number thus denied free secondary

training is even greater than the number denied any public

education at. all.14

Even after 1933, 'hen the State first required educational arrange

ments for blacks not. provided for at. home, many blacks outside Missouri's cities

-^compare, e.g., 1929 Mo. Laws 382, with 1945 Mo. Laws 1700. See X2325 (1936 St.

Dept.. Ed. Bull, noting school district.'s right to require "pupils to pay. ..the

cost, of.. .transport.at.ion [which] exceeds" the statutory maximum); 3d. of Educ.

v * Louis, 149 S.W.2d 878 (Mo. 1941) (school districts not. required to pay

for int.er-count.y trans fers).

14x210 (1928 Rep. at 137); 1858B. Accord, e.g., id. (46% of black children in

state denied free 12-grade education); N185 (1932 St. Dept.. Ed. Bull. at. 24) ("No

doubt, many districts having colored pupils enumerated made no plans last, year

- 7 -

remained without, free public education. In 1937, for example, for every rural

school district, providing school for its black children there was another pro

viding no arrangements at all; and as late as 1946, the State Supt. reported

that, the liberalization that year of the ceiling on reimbursible int.erdistrict.

transportation costs for the first time "provid[ed]n an "approach to equality of

educational opportunity. "15

Conditions in the 3-county area outside KCM followed the statewide

pattern. Frcm World War I to 1954, local school officials in only 6 of the 61

black settlements in the area (supra n.S) ever provided elementary schools for

their black children; 3 of the SSDs and their rryriad predecessor districts pro

vided absolutely no schools for blacks. T14799. At. the secondary level, access

to schools in the area was even more limited, especially as compared to access

for pupils to attend schools"). Under- and non-enumeration of blacks by

districts with numbers sufficient to require black schools was also conrron.

S.g., X210 (1921 Rep. at 161) ("There are not. as many colored schools as there

should be [because] some school boards... feel that these people should not. be

given a school if it can possibly be avoided"); X182 (p.ll); X1858B, 187;

T4255-72, 5323-5, 5782-92; see State ex rel. Morehead v. Cartwright, 99 S.W. 48

(Mo. App. 1907). See especially X54B (1910 U.S. Census shows blacks aged 6-20 in

area covered by FO predecessor districts; those districts enumerate no blacks

that, year); 54A (1940 census shows 334 blacks in township wholly encorrpassed by

CE, GV, HM and RT; those districts enumerate no black children that year).

Between 1868 and 1883, whenever any local district "refuse[d] or neglect!ed] to

provide for a [black] school as contemplated" by law, it was "the duty of the

State Superintendent, to provide for such school." 1868 Mo. Laws 170, repealed,

1883 Mo. Laws 187. During that short, period, the State Supt. established as many

as 60 schools a year. X208 (1873 Rep. at. 41; 1874 Rep. at 36). 15 *

15X114 (fig. 4), 187 (p.22), 184A (p.218), 212 (p.39), 189 (p.3). Throughout

the 20th century, moreover, those schools that, were provided blacks outside

Kansas City and St. Louis were inadequate: "In these schools, if they may be so

called, educational opportunities are practically non-existent. The typical

school is in operation for about six months a year. The teacher, usually...

young and immature..., has had little if any training above high school and fre

quently not. so much. The building is usually a miserable shack totally unfit,

for human habitation. Textbooks and reference books are scarce and usually

dilapidated. They are unsanitary, totally unattractive and generally

unsuitable." X210 (1929 Rep. at 122-3); accord, id. (1922 Rep. at 33, 1927 Rep.

at 147), 1858, 212 (1945 Rep. at 37), 189.

- 3 -

to white high schools. Concluded Dr. Anderson, "as a whole, from the

establishment, of Lincoln High in 1887...to 1954,...this 'was a one high school

area." T4334-5, A3.

Where 3-county area officials failed to provide black schools, they

also often failed to make alternate arrangements. Even the fragmentary

pre-Brown records available show scores of school districts in the area enu

merating blacks bat not. making any provision for their education. X37A, 37B,

39, 49. Of the 55 school—less communities noted above, for example, none pro

vided reimbursement, for their black children's tuition or transportation

elsewhere until LS became the first, to do so in 1931, and no district, joined LS

until IN in 1945, followed by PH and IK in the late 1940s, and LI in 1953.17

Moreover, while KCM elementary, junior high/vocational, and high

schools were the best in the state for blacks, (e.g., T1792-3, 1905, 3535), the

few black schools outside KCM were "quite inferior," whether compared to those

l^In 1925, there were 11 first class high schools for whites in the 11-SSD area,

none of any sort for blacks; in 1935, there were 12 high schools for whites,

.100% of them rated "first, class, " and 2 for blacks, rated "second" or "third"

class; and in the year before Brown there were again 11 first class white high

schools but no black high schools at. all. X39S-C, T4291-4, 4310-8. Both of the

black high schools intermittently operated by the SSDs for a decade or two after

1930 closed immediately upon black parents' insistence that the facilities and

programs be equalized with one available to whites. T317, 1354-6, 3748-50, X107

(p.54), 1830-4 (LI).

17 (a) (Letters in parentheses keyed to citations Ice low.) At a time when KCM's

tuition represented V4 of the average black family's income (T4313-4, 5355-3),

3-county area black parents were forced by their local districts' refusal (b) t.o

make provisions either to forego educating their children (c), or to bear the

expense of alternate arrangements, for example: attempting to enroll their

children in white schools (d) (efforts which succeeded only once, in the Owens

(FO) district, until 1910, when the Attorney General threatened prosecution for

integrating schools (e)); collecting private subscriptions to operate intermit

tent private schools (f); conveying their children t.o school at their own

expense (often via 2-hour trips each way (g)) by car, public bus, train, horse

and buggy taxi, or hired hearse (h), or simply by walking with their children

the 5 or more miles to school along the same road traveled by white school buses

(i); boarding the children with strangers (j), or with friends or relatives in

the city (often requiring the children t.o move 3 or 4 times before finishing

school) (k); breaking the family into 2 households — mother and children

- 9 -

in I<CM or to the white schools in their cwn districts. 18 Overall, education for

blacks in the 3-count.y area cutside KCM was "a system of no schools, poor

schools, a system where tuition [and] transportation was not, provided quite

often." T4328 (Dr. Anderson).

* * * *

The district, court, found "an inextricable connection between schools

and housing in the Kansas City area." Because [p]eople gravitate[d] toward

school facilities,'" the "'location of schools influence[d] the patterns of

residential development, of [the] metropolitan area and ha[d] important impact, on

composition of inner city neighborhoods.’" 593 F.Supp. at. 1491 and 6/5/84 Opn at

101, quoting Swann, 402 U.S. at 20-21. Missouri's peculiarly interdistrict,

system of locating separate schools affected 3 residential patterns: the depo

pulation of blacks in suburban areas outside KCM; the increase in KCM's black

population; and the all-white suburbanization of the 3-county area outside KCM:

establishing residency in town where schools were available; father staying at

home to earn a living or giving child up for adoption to parents in the city

(l); or simply foresaking jobs and moving the entire family to the city (m).

Citations: (a) E.g., X185 (p.21), 206, 224A, 1807, 1831, 2392, 3595, (b)

E.g., T124, 429, 527, 543, 1125, 1254, 1678, 2843, 3142, 4327. (c) E.g., X52B,

T317, 530, 590, 1009, 1100, 1235, 1329, 2687, 3206. (d) E.g., T527, 533 (MK);

946 (BS/FO); 1687 (LS); 3142 (PH). (e) E.g., X49, 6 6. (fTE.g., T369, X39, 49

(NK); T4286, X39, 49 (Ed). (g) E.g., T1623, 1747, 2133. (hTELg., T1470, 3243,

1363, 3178, 948, 146, 421, 1255. (i) E.g., T423, 1009. (j) E.g., T890 (BS/KC),

3532 (PH/KC). (k) E.g., T890 (BS/lN/KCM/Kansas (KN); 2726 (PH/tfebraska/KN/KCM);

1134 (LS/IN, LS/KN), 3183 (PH/KCM/KN/Jeff. City); 1115, 1329 (.Platt.sburg/KCM);

1146 (LS/kCM); 1830, 2497, 3268 (Ll/Ex.Sp./KCM); 923, 26G3.

(NK/Plattsburg/Ex.Sp./Ll); 828, 1356, 1713 (IN/KCM); 127, 323 (NK/KCM), 890,

951, 1806 (BS/KCM), 1516, (Harrisonville/KCM). (1) E.g., T791 (BS/lN/KC); 890

(BS/IN); 708, 1203 (LS/KC); 1642, 1688. (m) E.g., T324, 434 (NK/KCM); 952,

(BS/IN); 922 (BS/LI); 1199 (LS/KCM), Cans D21 (Ll/KCM); 1053, 1064

(Plattsburg/KCM); X40.

18E.q ,, T16835; 818-24, 1743-6, 3748-50; X200, 2400 (IN); 2275 (PH); T482-3,

928, 1829, 2029, 2379, .3517 (LI); See X39-A, 73-8.

10 -

1. Between 1900 and 1950, both the number and ratio of black school-

aged children in the 3-county area dropped substantially, led by families with

school children, vhose proportion declined from 36 to 21% over the period.

X49A, 51, 54; T10825-30.

Total and Black Enumeration, 1900-54 (X53E)

Missouri's segregated school system,19 and local witnesses belcw repeatedly con

firmed their conclusions.20 Overall, the interdistrict, system of segregated edu

cation in the 3-county area "meant that blacks were penalized for being

dispersed" among whites; by law they "had to live in concentrations in the

city...to have any reasonable hope for any kind of education." T4335 (Dr.

Anderson).

"Undeniably," the court below concluded, "some blacks moved" out of

districts which did not. "’maintain the state-required separate schools [for

Instate Education Commissioner Baker, for example, found that. "[o]n account of

the lack of school facilities in many small towns and rural districts there is a

desire on the part of negroes to move to the larger cities...and congested

centers," and "inclination...increasCing] from decade to decade." X210

(1922 Rep. at. 31). His successor, Lee agreed, e.g., X210 (1924 Rep. at. 197), as

did the school surveyers Lee hired to look at Missouri schools as the Depression

began, X184, and the statutorily created Negro Industrial and Educational

Commission, X182 (p.ll). Accord, XK30, A91

2°Eppie Shields, for example — a lifetime NK-predecessor-dist.rict. resident,

whose parents had t.o pay for him to be educated in LI (only months before

hearing of Brown) and who had to walk miles to get. to school — moved his own

family t.o KCM in 1954 because "[t.]here wasn't, any black schools out there, and I

- 11 -

blacks].•.to districts, including the KCMSD, that provided black schools." 593

F.Supp. at 1490. "Before 1954 access to schools [along with]... economics and

job opportunities were...major factors in black migration" and in 'blacks

cho[osing] to move into the KCMSD," id., "prorrpt[ing] the depletion of black

people from the surrounding towns...in the metropolitan...Kansas City area,"

T16693, cited in id.

It is "inpossible to get a count of all" children residentially

affected by these segregation-induced forces (T4312-4 (historian Anderson)): the

pre-Brcwn records the SSDs kept regarding the fact, and number of black children

living there are fragmentary at. best.? 21 the districts kept, no records showing ’new

and where their black children were actually educated over most, of the period;22

and the district, court, ruled the long and tedious process of "recreating" the

missing documents through testimony 30 to 120 years after the fact, unnecessary, * 21 22

didn't plan to go through the frustration and problems that, my folks did to

get...my children in school. T434; accord, e.g., T182, 324, 474, 539, 548, 708,

761, 855, 920, 933, 951, 1021, 1053, 1143, 1292, 1339, 1400, 1656, 1689, 3167,

3598. Dr. Orfield generalized: "If you are a member of a racial minority who

lives in an area...in which all public offices and all the educational offices

are controlled by the other racial group, where there is a history of complete

segregation and where your [children] are not permitted to attend any of the

schools that, are offered to children in that, district., all you have to do is

imagine yourself in that situation to realize that it would have an inpact, on

whether you chose to live there or not." T14797. The learned literature reaches

the same conclusion (see T4349-50, 16846-71, 18796-822, 21117-24), typified by

Gunnar Myrdal's An American Dilemma that, "[l]ike many other oppressed people,

Negroes place[d] a high premium on education," and were "stimulateed]" to

migrate by a desire for "access to more and better schools." T18803.

21T4255. Inaccurate at worst., supra n.14. Testimony established the presence

of black school-aged children in numerous SSDs or predecessor districts in years

in which no official records are available. Compare, e.g., X49, with 1785 (HM);

1826-28; T317, 531, 566 (NK); 726, 756 (BS), 1437-8, 897-3, 2265 (FO); 3138-43.

Compare also Campbell D146-51 (LS records show no black students there in

1911-30) with X49 (LS records at. Jackson County Historical Society show blacks

in nearly all those years).

22virtually no records were kept, during the period when the system's effects

were most pernicious. (1) No district, in the area took responsibility for

paying for its black students' education elsewhere until 1931 in one instance

and the 1940's in all others, so no records were kept, of where they attended

- 12 -

cutting off further presentation of such evidence. See infra n.126. The

available evidence shews:

• Although 21% of the black students in the 3-county area as of

1900 lived in suburban areas outside KCM, their number shrank

75% (1077 students) by 1954, and their proportion in the

3-count.y black enumeration dwindled to 3%. X53E.

« While fragmentary school records show that 10 of the 11 SSDs

or their predecessor districts had black students prior to

1954 (supra n.8 ), 8 of those districts (BS, CE, DO, GV, HM,

LS, NK, RT) had no black students left to enroll by 1954 —

and did not. enroll any until the 1960s or 1970s — and 2 of

the remaining 3 have yet to enroll as many blacks in the

post.-Brcwn period as they did at their pre-1954 black

enrollment peak. X53, 53G; compare id. with X49.

• In 1929, the State reported that, while only 46% of the sta

te's black elementary school students attended schools in KCM

and St. Louis, 84% of the high school students in the state

were attending there, a 38% disparity suggesting that 2090 of

the 4620 black high school students there were interdistrict.

transfers. X210 (1929 Rep. at 122).

• The "oral history" evidence plaintiffs were permitted to pre

sent. in lieu of accurate recordkeeping by the SSDs allowed

just, under 800 examples of interdistrict. transfers fretn the

3-count.y area, representing in Dr. Anderson's uncontradicted

expert, opinion only a small "fraction" of the number of

children actually affected. X40, 1775, T4312-4.

• In the decade before Brawn, there were sufficient, nonresident

students in Lincoln High to cause the Urban League to demand

that, transfers be barred as a solution to overcrowding, and

to cause KCM a few months before Brown to prepose denying

nonresident blacks admission. *

school. T4312-4. (2) "One of the major incentives in the whole process was not.

t.o become a record, that is, for families with school children to establish

residency or to move in and live with relatives or friends because of the high

cost, of tuition and. . .transportation that were not reimbursed, so you don't.have

the records available." T5856 (Anderson). Thus, while KCM's Beard strictly for

bade black nonresident students to attend without paying tuition (T4428,

X226-27A), black teachers and principals ignored known nonresidents who moved in

with relatives and registered as residents; and it was "general knowledge" among

them that, many children did so. T2110-1; see T1686, 1713-4, 1806-7, 3531-2.

Overall, "[tjhere's no way to quantify or establish anything close to the

complete record of people involved in the interdistrict. system." T5856

(Anderson). See X1770; T138-9 (stipulation regarding unavailability of inter

district- transfer records).

13

• The only official, though non—racially coded, compilation of

inter-district, transfer data available in all the defendant

districts1 files shews that in the 6-year period preceding

Brcwn, over 2200 of the total enrolling high school children

in the KCM were "non-resident high school pupils," of whan

anywhere from 240 to 600 or more may have been black. 23

• The testimony at trial revealed dozens of people who, along

with their children — and their children’s children and

grandchildren — never returned to the suburbs and remained

in KCM after commuting or moving there for school. 24

• The dual interdistrict. system resident.iallv "affected

everyone that, was trying to get [an] education. ... [F] ami lies

and schoolchildren that, wanted to receive a high school edu

cation in this area were sent, to central Kansas City, which

was about the oily place to get a high school education. .. .We

also knew that there were areas like NIC that did not. maintain

elementary schools for children. They had to cone into

Kansas City. LS closed the elementary school down in 1910.

They. ..first went, to Kansas City and then to IN. IN closed

Young High School. They came into the city.... In all the

areas that did not maintain schools for blacks, it had an

effect, because [blacks] could not. live there and have any

access to education." T4334-5 (Dr. Anderson).

2. The district, court, found the effects of Missouri1 s interdistrict,

segregated school system on blacks migrating to the area from outside the state

23X1770, discussed, 6/5/84 Opn at 45. The "251" SSD-KCM transfer figure cited by

the court, from T4557 (6/5/84 Opn at 16, adopted verbatim from p.36 of tine SSDs'

preposed fact-findings) is wrong. The figure comes from the question of a

defense attorney; was not verified toy the witness (who "didn't check" it.

because it would "distort" the "qualitative" value of the data to quantify it,

T4313-4, 4557, 5857); and was admittedly only .an "approximation" of X40 by

defense counsel who conceded his "math may be off" — as indeed, it was toy quite

a bit. More inport.ant.ly, defense counsel expressly stated in asking the

question that the 251 figure represented transfers "from current defendants.

I'm not. talking about any predecessor districts." T4557-8. Most, of the SSDs

did not. exist, until the late 1940s or early 1950s (T6078-86, X960), and a

good many of the transfers in X40 are from SSD predecessor districts. E.g., X49

(70% of NK's pre-1954 blacks and 100% of BS's and FO's were in predecessor

districts). Accordingly, even were defense counsel's "math" correct, as to

transfers from the current, "suburban school districts to the KCMSD" (6/5/34 Opn

at. 16), it emits many of the transfers for which the SSDs are now legally

responsible. See nn.124 & 125.

24E.g., T324 , 434, 1037, 1059, 1143, 1207, 1688 , 2133 , 2698 , 2769 , 2779 , 3228,

9438, 9511, Edwards D39-58; see T2839 (of the 44 transfers PH witness could

name, 57% later lived in KCM).

14 -

even greater: "[S]chools" would "often...influence.. .what housing choice would

be made within the city" by the "influx of blacks... frcm southern and border

states." 593 F.Supp. at 1490. "Regardless of their motivation for coming, once

here, blacks settled in the inner city, or the 'principal black contiguous

area'" where KCM's "segregated facilities [for blacks] with, segregated

staffs.. .were located." Id. at 1491, 1492. "This in-migration coupled with a

high birth rate resulted in the Kansas City black population doubling" from 1940

to 1960. Id. at 1490.25

3. "The availability of schooling in the city, the unavailability out

side, the quality inside versus the low quality outside" were also "deterrents

to blacks participating in the suburbanization process" that began among whites

in the 3-county area in the 1920s and took off in the decade and a half before

Brcwn. T5853 (Anderson) A4-5; X49A, 51A. As the State's expert, geographer

testified, the SSDs' boundaries over time became "barriers" to black subur

banization by taking on "symbolic meanings" — in part., he testified because of

•^Expert, and lay testimony bears out the court's conclusions. (Jimmie Marie

Thomas, World War II migrant to the area from Texas, did not consider living in

SSDs because "I planned to have children and I knew in the suburbs that, the

black children after they get. out. of elementary school came into Kansas City for

high school, and I certainly didn't want to buy a heme that would take us pro

bably 15 to 25 years to pay for and have to transport, riy kids into Kansas City

when they got out of elementary school" T3598). E .g ., T21120 (Dr. Amos Hawley,

president of the American Sociological Ass'n: "there's an abundance of litera

ture in all...areas, historic, demographic, survey, that indicate that schools

are of paramount, concern for blacks, in [short, and] long distance moves. The

job. . .may be the first, statement of objective but. once they arrive, schools

become extremely important."); T3598.

Lincoln High School in particular acted as a "magnet." not. only for black stu

dents but. for black residential settlement, in its immediate vicinity and black

commercial development nearby. T14782-99 (Orfield)? accord, 16846-9 (Weinberg).

See T325, 434, 922 (blacks moving from SSDs to KCM typically bought, homes in KCM

as close to a school building as possible). On the other hand, while war and

related industries opened up numerous jobs to blacks in or near the SSDs from

the early 1940s on (e.g., X138A; T5826, .18977, Jones D23, Orfield D6 ; plants in

or near BS, CE, PO, GV, HM, NK, PH, RT), the affected SSDs either enumerated no

black (children at. the time or experienced black enumeration declines. X49,

T4615. See also T922, 951, 1292, 1400, 1682, 2192, 3168 (black families roving

- 15 -

blacks' "unpleasant experiences [there] in the past. . " * 26

Dr. Orfield described the overall residential impact, of Missouri's

int.erdistrict system of segregation as a tragically lost opportunity for the

high degree of residential integration cnce characterizing the 3-county area to

translate to metropolitan-wide school integration when segregation was barred.

T14805-6, 15286-7. See also T19259 (testimony of State's geographer that "the

existence of a core of blacks caused by [governmental segregation] in the Kansas

City area would have long lasting effects because.. .blacks tend to move short

distances from the core. ..and in-migration [of blacks] tends to focus on that

black core as a result, of... informational networks" ) . 27 * * As the district, court,

found, "[t.]he intensity" of the resulting "segregation is demonstrated by the

fact that, the average black family [in the city] lives in a census tract, that is

85% black while the average white family [in the suburbs] lives in a census

tract, that is 99% white." _Id. at 1491, citing T14745.

B. Missouri's Metropolitan-wide Dual Housing System.

"In the past, the State has taken positive actions which were discrimi-

away frcm job location in order to alleviate effect of segregated schools).

26T22076, 22091 (citing NK as example); compare T182 (former NK resident who

transferred, then moved to KCM for school and decided not to return thereafter

because "I wouldn't, want, to subject, my children to. ..the things I went through").

The same forces in reverse shaped white suburbanization. Thus, cne fallout of

the state's dual system was to "create an atmosphere in which...white individuals

[developed] prejudice against blacks" and black schools. 593 F.Supp. at 1503.

By identifying the SSDs as "white districts...intended for white families" and

KCM as the "one" district, in the area for black students and teachers, then

attaching perceptions of superiority to the "white districts" and of "undesir

ability]" to KCM and its black schools, the int.erdistrict. dual system

encouraged white families to move from, or steer clear of, the city and move to

the suburbs. Orfield D67, T4334, 14807, 16704. "As blacks moved or were busied

to the schools in the area, iAhit.es moved out.." 593 F.Supp. at 1494.

27Accord, T4444, 14782, 16707, 18968. See X3003A (l/3 to 2/3 of households

now living in all-black tracts in KCM core area have lived in the same house

since 1959, the earliest, date for which data are available. In addition to

residential effects, the district, court, "confirmed. .. .the conclusion [in]

Brcwn I," that "forced segregation...ruined attitudes...'in a way unlikely ever

- 16 -

natory against, blacks," chief among them, "enforcing racially restrictive

covenants." 593 F.Supp. at 1503. "These actions had the effect, of placing the

State's imprimatur on racial discrimination..., and ha[d] and cont.inueE ] to

have a significant effect, on the dual housing market- in the Kansas City area."28

Id. By affecting where thousands of black and white families come to live,

moreover, these actions were "inextricably interwined" with "school

composition." 6/5/84 Opn at. 101; see T12974-6 (A21-26), cited, 593 F.Supp. at

1491.

1. State-enforced racially restrictive covenants. "Racially restrictive

covenants were intended to cause housing segregation" and "were enforced by the

courts of Missouri until [5 years] after Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948)."

593 F.Supp. at 1497.28 As urban planner Gary Tobin testified, such covenants

were recorded on "a large proportion of the residential land uses in 1947, "30 and

created both (1) a "minefield effect...by their widespread location throughout,

the area" outside the black community surrounding Lincoln High School, which

"serv[ed] as an effective barrier to black movement" outside the ghetto and into

to be undone1" and created a "general attitude of inferiority among blacks

[which] produces lew achievement [and] ultimately limited employment, oppor

tunities and causes poverty." Id. at 1492 quoting Brcwn I, 347 U.S. at 494.

28By "dual housing market., " the court, referred t.o the "system. ..whereby blacks

were served by...a different, real estate community than whites" and in which

"blacks were steered only. ..to southeast. Kansas City or the ghetto...and were

unable to buy outside that, area," while "whites were steered elsewhere," causing

"that neighborhood to turn over [from white to black] block by block." T12008-9,

cited 593 F.Supp. at. 1491.

28Compare Weiss v. Leaon, 225 S.W.2d 127 (Mo. 1949), with Barrow v. Jackson, 346

U.S. 249 (1953). 30 *

30See 13023; X22 (restrictive covenant, location nap overlaid by map of school

district, boundaries showing that, all SSDs but. FO had racial covenants, that all

areas residentially developed as of 1947 outside KCM's black core area — either

had or were near other .areas which had racial restrictions, as were numerous

areas not. yet developed, and that, a nuirtoer of small black communities in the

3-count.y area outside the central black area were ringed by restrictive cove

nants so that, they could not. expand); T13030, 14838 (extensive 3-count.y area

- 17 -

the SSDs,31 and (2) a "bursting dam phenomenon, " characterized fey "a very rapid

migration of blacks to an area and. ..rapid outmigration of whites" "where

restrictions were broken."32

2. The State's impact on FHA's refusal to insure mortgages on homes

by racially restrictive covenants. Since 1934, "FHA [has] guaranteed or insured

payment, of residential mortgage loans for.. .qualified [homebuyers] making it.

possible for [them] to purchase homes with very low down payments and interest

rates below the national average." 593 F.Supp. at 1496. Between 1936 and 1947,

FHA. appraisal manuals provided that racial covenants and concern for racial com-

patability "would tend to insure a stable community [and] erihanc[e] the value of

property" and cautioned agency personnel against insuring mortgages on hemes

unless they were (a) covered by racially restrictive covenants, (b) located in

"racially homogenous" neighborhoods, and (c) geographically removed from black

or integrated schools. X1304 (A98); T13047-8. "[Tjhereafter," as lat.e as 1959,

FHA's manuals continued to place "emphasis...on such considerations as

[avoiding] a change in occupancy...from one user group to another" and on a pre

ference for "social homogeneity" and "compatibility among the neighborhood

occupants." 593 F.Supp. at. 1497; X1305. Consequently, as the board chairman of

one of Kansas City's largest mortgage conpanies testified below, local home

press coverage of racially restrictive covenants before Shelly); T1316, 1897,

2985, 3356, 3808, 3853, 5063, 9927, 13671, James D59-60; O'Flaherty D15;

Thurman D54 (difficulties encountered toy witnesses in finding housing due to

racial covenants).

31T13037 (A23). Like segregated schools, restrictive covenants funneled in-

migrants into the black-concentrated areas near where KCM's segregated schools

were located, insuring that, "when the schools were opened [after Brown], they

would be segregated." T14878-79. See also 593 F.Supp. at 1492-3. 32 *

32T13024, 13034-35. In addition, the "widespread adoption of restrictive

covenants...limited black housing supply...confined [blacks] t.o older

areas...[and] resulted in overcrowding, high density, and deteriorated

conditions" in the area surrounding KCM's all-black schools, contributing to

white flight out of the area. T13033-5, cited 593 F.Supp. at. 1491. Accord,

- 10 -

finance institutions could not. get. FHA insurance in areas Where racial restric

tions were not in force ' until 1962, when President. Kennedy issued Executive

Order 11063.33

The court, expressly tied FHA's adoption of these policies to Missouri's

restrictive covenant enforcement: "without a doubt....[covenants] did have an

effect, on the market value of residential property," and other actors in that

market, including FHA, "faced with this reality could not. ignore it in iraking a

determination [of] the maximum risk" they were willing to incur. Id.34

3- State—FHA impact, on the dual housing market.. The State's "positive

act-ions.. .discriminatory against blacks... created an atmosphere in which, private

white individuals could justify their bias...against blacks" and "encouraged

racial discrimination by private individuals in the real estate, banking and

insurance industries," who, "[t.]here is no doubt-..., did engage in discrimina-

T14848-9 (Orfield). As State's expert. Clark noted, the most longlasting effect,

of restrictive covenants may be the retarding effect, they had on black acquisi

tion of equity in a period of tremendous equity formation by whites. T19157-8;

accord T14867, 15416. ("In the 1925 to '40 period, .. .only 15 new homes were

available to blacks throughout this entire city").

33Thompson D74 , 84 (A61-62) ('until 1962, "FHA and VA wouldn't, insure and guaran

tee loans [in the Kansas City area] unless there was a [racial] restriction

involved, and most lenders on residential property were relying heavily upon the

FHA and VA for their protection. So that as long as that, remained their posi

tion, the lendor really had no choice but. to observe the restriction."); James

D59, 82 (HUD appraiser stating utilization of restrictive covenants was not pro

hibited by FHA insurance procedures until early 1960s); X1239A (new racial cove

nants recorded in 3-county area as late as 1960); T1316, 3853 (blacks

encountered difficulty buying covenanted property in early 1960s); Bridges D90,

X1627 (owner refused to sell HAKC property in RT for public housing, citing

racial covenant). See also X2854, T98S9-92 (between 1950 and 1969, expressly

pursuant, to FHA regulations, major Kansas City area title company recited all

pre-2/5/50 racial covenants in title insurance policies: practice not changed to

forbid references to all racial covenants imt.il FHA "reduced the hazard" of

doing so by ”revok[ing] its [1950] regulation which [only] made loans ineligible

for insurance ...if racial rest.rict.ions were imposed after 2/15/50"). 34

34As a result., the "15,000 homes in the KCMSD" insured by HIA prior to 1950, the

tens of thousands more insured by FHA in the reminder of the metropolitan area

during the pre-1962 "racial and social compatibility" regime, and the even

greater numbers included in subdivisions whose developers, of necessity, con-

- 19 -

t.ory practices such as redlining, steering and blockbusting." Id. at. 1503.35 As

a result., "[a] large percentage of Whites do not want blacks to reside in their

neighborhood" and "move[d] out." of KCM's southeast corridor to the suburbs when

blacks came to reside there. 593 F.Supp. at 1503, 1497; see 6/5/34 Opn at 41.

The Court, concluded that, by establishing some "areas in which minori

ties were not-...able to obtain housing" and other areas — most, particularly,

the areas surrounding and immediately to the south and east, of KCM's all-black

schools — into which minorities "were steered or channelled" (T12339, cited,