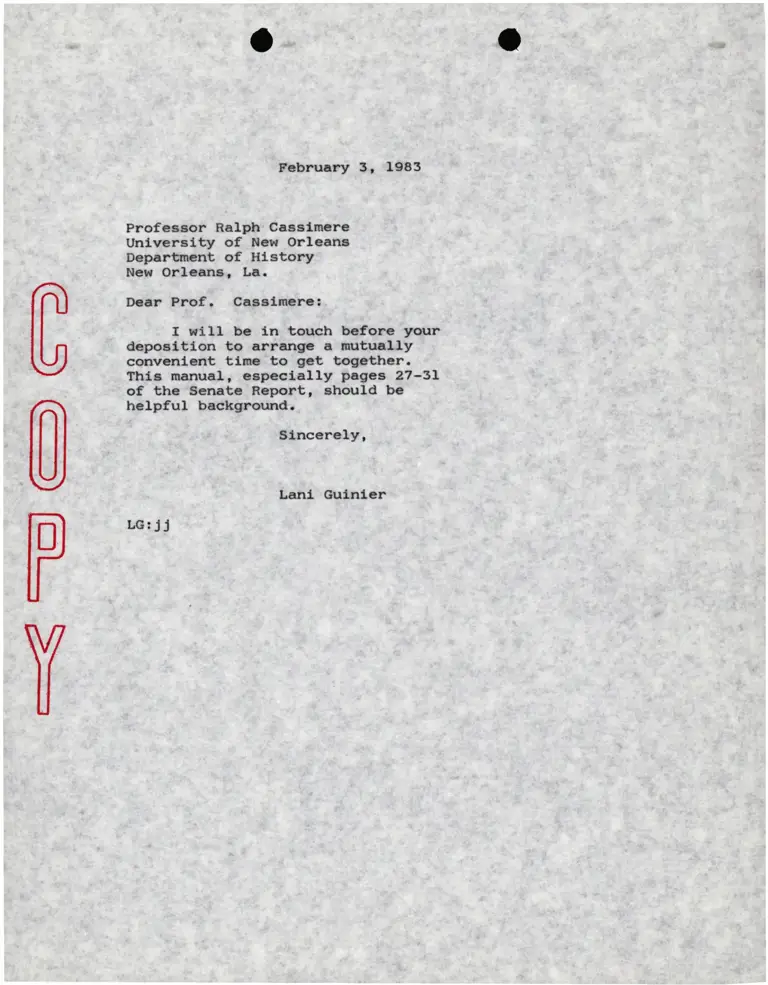

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Prof. Ralph Cassimere (University of New Orleans)

Correspondence

February 3, 1983

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Prof. Ralph Cassimere (University of New Orleans), 1983. 6ce3cd97-e492-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/03ef0148-ba81-4b55-ab1b-153d2397551e/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-prof-ralph-cassimere-university-of-new-orleans. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

O.*

Fcbnrary $, '1983

Profcaeor Ralph' Carelmcrc

Unlverelty of Ncw Orlearr

D.ptrtncnt of HlstorY

New Orloent. t!.

I)car Prof. Cryetrcrcr

.

I rtltr llc 1n touch utio." yqrr

dcpoaltlon to arratrgp a nrtually

cqtvcnlcnt tlnt:to gct togcthcr.

Ttrle rnanual, capcctally pogct 27-3l,.

of thc 'Scnatc neport, ehould bo

hclpful bechground.

i . Slnccrc1y,

Lanl Gulnlcr

I,G: JJ

.d!a

G

0

P

Y

i.:$.

Ir