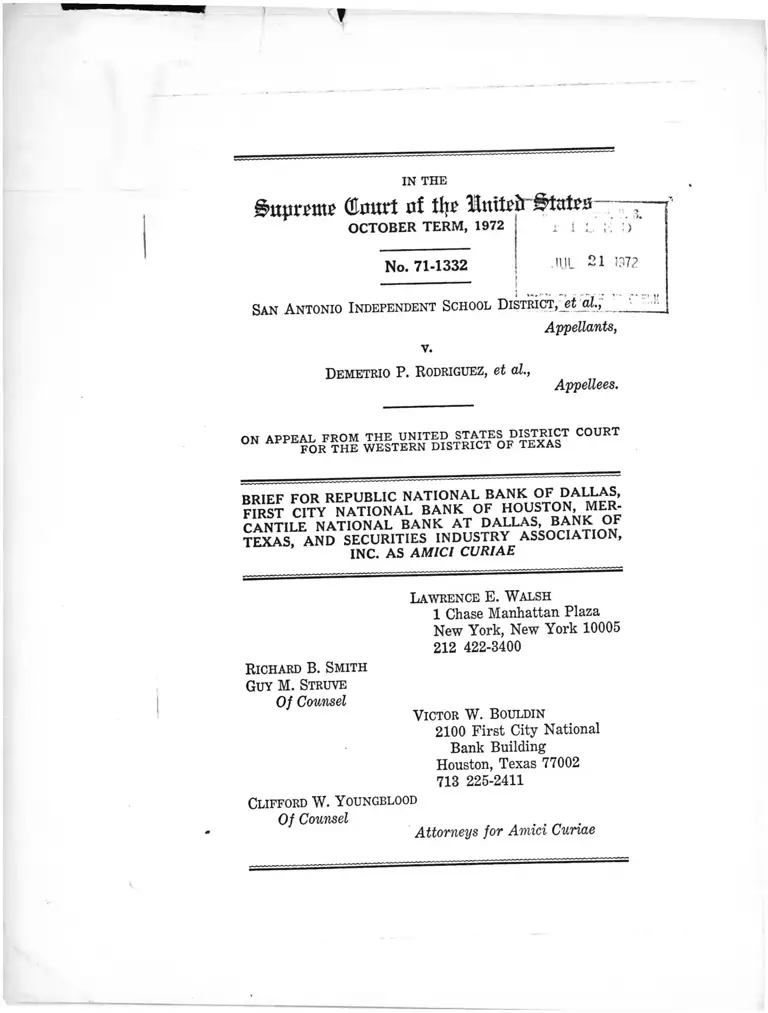

San Antonio Independent School District v Rodriguez Brief of Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

July 21, 1972

55 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. San Antonio Independent School District v Rodriguez Brief of Amici Curiae, 1972. 0c157b98-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0401ba4d-a6f0-42d2-b7a3-89d8ac969c9e/san-antonio-independent-school-district-v-rodriguez-brief-of-amici-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

f

IN T H E

§>upr£Jtt£ d n u r t o f tf|£ ,

OCTOBER TERM, 1972

No. 71-1332

'■)

. 1UL 21 137?

Sa n A ntonio Independent School D istrict, __

Appellants,

v.

D emetrio P. R odriguez, et al.,

Appellees.

" v

n » j A P P F A L f r o m t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s d i s t r i c t c o u r tO N A P P E A L F R O M iH f i u D IS T R IC T O F T E X A S

BRIEF FOR REPUBLIC NATIONAL BANK OF DALLAS,

FIRST C?TY NATIONAL BANK OF HOUSTON MER

CANTILE NATIONAL BANK AT DALLAS, BANK OF

TEXAS ANDSECURITIES INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION,

imp A M i n i CU RIAE

Law rence E. W alsh

1 Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, New York 10005

212 422-3400

R ichard B. Sm ith

Gu y M. Struve

Of Counsel

V ictor W . B ouldin

2100 First City National

Bank Building

Houston, Texas 77002

713 225-2411

Clifford W . Y oungblood

Of Counsel

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Question Presented......................................................

Interest of Amici Curiae.............................................

Statement......................................................................

1 . The Nature of Texas School District Bonds

2. The District Court’s Clarification of Orig

inal Opinion....................................................

3. Judicial Protection of Outstanding and In

terim-Issued Bonds in Other Jurisdictions

Summary of Argum ent...............................................

A rg u m e n t :

I— This Court Should Reaffirm the District

Court’s Protection of Outstanding and In

terim-Issued Bonds ...............................

II__This Court’s Decisions Establish That the

District Court’s Holding Should Not Be

Applied Retrospectively ...............................

HI__Retrospective Application of the District

Court’s Holding Would Offend the Prin

ciples Embodied in the Contract Clause and

the Due Process Clause.................................

Conclusion

22

11

T able of A uthorities

Cases

AtCv t ° \ l ' Ry■ v- Pum Comm’n’ PAGE

Burruss V.Wilkerson, 310 F. Supp. 572 (W.D. Va.

1969), aff d mem., 397 U.S. 44 (1970) ................. i 7_i8

Chevron Oil Co. v. Huson, 404 U.S. 97 (1971) 17-19

Cipriano v. City of Houma, 395 U.S. 701 (1969 ) . . . 13 16

City of Phoenix v. Kolodziejski, 399 U.S. 204

(1970) .............................................. 13 16 17

City of Waco v. Mann, 133 Tex. 163,127 S. W.2d 879 ’

(1939) ......................... .......................................... b

Desist V. United States, 394 U.S. 244 (1 9 6 9 ).......... 18

Erie R.R. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1938) ............ 19

Gelpcke v. City of Dubuque, 68 U.S. (1 Wall ) 175

<1863) ............................................................ ' ......... 19

Hollins v. ShofstaU, Ariz. Super. Ct., Maricopa

County, No. C-253652, June 1 , 1972 ................. . 12

Laconia Bd. of Educ. v. City of Laconia, 285 A 2d

793 (N.H. 1971) ............................................ n

Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618 (1965)................. i 8 19

L°V{19Sl)ity °f DallaS’ 120 ^ 351’ 40 S-W*2d 20 ’

........................................................................ 6

Mclnnis v. Shapiro, 293 F. Supp. 327 (N.D. 111.

1968), aff d mem. sub nom. Mclnnis v. Oailvie

394 U.S. 322 (1969) ..................................... 9 ’ 17_lg

McPhail v. Tax Collector, 280 S.W. 260 (Tex Civ

App. 1926) ...................................................... ’ ' 6

Morley Construction Co. v. Maryland Cas Co 300

U.S. 185 (1937) ............................................ ’’ 14

Nashville, C. & S.L. Ry. v. Walters, 294 U S 405

(1935) ............................................ [.......................... 4-L

PAGE

National Surety Corp. v. Friendswood Ind. School

Dist., 433 S.W.2d 690 (Tex. Sup. Ct. 1968) ........ 6

Robinson v. Cahill, 118 N.J. Super. 223, 287 A 2d

187 (1972) ............................................; ............ i i _12 lg

Rodriguez v. San Antonio lnd. School Dist 337 F

Supp. 280 (W.D. Tex. 1971) ................... ’ . 6, 7, 8,14,18

Serrano v. Priest, 5 Cal. 3d 584, 487 P.2d 1241 96

Cal. Rptr. 601 (1971) ............................... ’ 9.1Q

Spano v. Board of Educ., 68 Misc. 2d 804, 328

N.Y.S.2d 229 (Sup. Ct. Westchester County 1972) 15

Sivarb v. Lennox, 405 U.S. 191 (1972) ................. 14

Sweetwater County Planning Committee v Hinkle

491 P.2d 1234 (Wyo. 1971), 493 P.2d 1050 (Wyo

1 9 7 2 ) .................................................................................... 10-11

Van Dusartz v. Hatfield, 334 F. Supp. 870 (D. Minn.

1971) .........................................................................

Von Hoffman v. City of Quincy, 71 U.S (4 Wall )

535 (1866) ................................................ ’ ■ 2Q

Walz v. Tax Comm'n, 397 U.S. 664 (1 9 7 0 )............... 21

Statutes and Rules

Sup. Ct. Rule 4 2 .............................

Texas Const., Art. 7, § 3 ............. ................................. r f

Texas Educ. Code § 12 .29 .......... . . . . . ! . ! ................ r

Texas Educ. Code § 13 .102 ............ V\

Texas Educ. Code § 13 .107 ........................................ 7

Texas Educ. Code § 20 .01 ........ ........................... r i '

Texas Educ. Code § 20.04 ....................... £

Texas Educ. Code § 20.06 ___ ’ ’ ................................. ^

Texas Educ. Code § 23.28 ...... ..................................... 7

Texas Educ. Code § 23.76 .......... ........................... I

Wyo. Const., Art. 16, § 5 ............. ...............................

Wyo. Stat. § 21.1-253 ............. .................................

IV

PAGE

Other Authorities

American Banker, Nov. 11, 1971 ............................... 9

Comment, The Evolution of Equal Protection: Edu

cation, Municipal Services, and Wealth, 7 Harv.

Civ. Rights— Civ. Lib. L. Rev. 103 (1972) ........... 15

Daily Bond Buyer, Nov. 15 ,1971 ............................... 9

Moore, Local Nonproperty Taxes for Schools, in

Johns, Alexander & Stollar, eds., Status and Im

pact of Educational Finance Programs (National

Educational Finance Project, Volume 4) (1971) 7

Slawson, Constitutional and Legislative Considera

tions in Retroactive Lawmaking, 48 Calif. L. Rev.

216 (1960) ................................................................. 20

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Governmental Finances

in 1969-70 (Series GF-70, No. 5) (1971) ........... 4

U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare,

Bond Sales for Public School Purposes 1970-71

(DHEW Publication No. (OE) 72-63) (1972) . . 4 ,7

IN THE

j$>uprpm p (H m trt o f t ljp l lu i t P i i S t a t e s

October Term, 1972

No. 71-1332

+

Sa n A ntonio Independent School District, et al.,

v.

Appellants,

Demetrio P. Rodriguez, et al.,

Appellees.

O N A P P E A L F R O M T H E U N IT E D S T A T E S D IS T R IC T C O U R T

F O R T H E W E S T E R N D IS T R IC T O F T E X A S

-----------------♦-----------------

BRIEF FOR REPUBLIC NATIONAL BANK OF DALLAS,

FIRST CITY NATIONAL BANK OF HOUSTON, MER

CANTILE NATIONAL BANK A T DALLAS, BANK OF

TEXAS, AND SECURITIES INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION,

INC. AS AM ICI CU R IA E

Amici curiae, four Texas banks which hold more than

$100 million in principal amount of Texas school district

bonds and the Securities Industry Association, Inc. (herein

after “ SIA” ) , many of whose members are underwriters

of Texas school district bonds, submit this brief to urge

this Court, if it should affirm the decision of the District

Court, to make clear that its decision should only be applied

prospectively from the ultimate determination of the action,

and should not affect the enforceability of Texas school

district bonds outstanding at the time of the District

2

Court’s decision (hereinafter “ outstanding bonds” ) and

bonds authorized and issued prior to the ultimate disposi

tion of this action (hereinafter “ interim-issued bonds” ).

Counsel for all parties have given written consent to the

filing of this brief pursuant to Rule 42 (2 ).*

Question Presented

The amici banks and the SIA do not wish to, and do not,

take any position with respect to the District Court’s basic

holding that the present Texas system of financing public

education denies equal protection. This brief is addressed

solely to the following question:

Should any restructuring of the system of financing

public education in the State of Texas pursuant to

this Court’s decision on the present appeal protect the

continuing collectibility of property taxes levied to

pay the principal and interest on outstanding and

interim-issued Texas school district bonds?

The District Court in its Clarification of Original Opinion

dated January 26, 1972 held that this question should be

answered in the affirmative, and we support this holding.

* The amici banks and the S IA were denied leave to intervene of

right in the District Court, and appealed directly to this Court from

this denial in order to establish their right to participate as parties and

to present two issues not then fully presented by the existing parties,

(1 ) the need to assure the continuing enforceability o f outstanding

and interim-issued bonds, and (2 ) the need to allow the states broad

flexibility in framing any new system of financing public education.

Republic Nat’l Bank v. Rodriguez, Oct. Term, 1971, No. 71-1339.

This Court dismissed the appeal for want of jurisdiction, but granted

leave to file the jurisdictional statement as a brief amici curiae in con

nection with the jurisdictional statement on the present appeal pur

suant to Rule 42(1). 40 U .S .L .W . 3575 (June 7, 1972). This brief

is limited to the first issue presented in the earlier appeal, because we

believe that the need for flexibility has now been adequately presented

by the earlier jurisdictional statement and by other amici.

3

Interest of Amici Curiae

About $3 billion in principal amount of Texas school

district bonds were sold during the 25 years 1946-1971 (R.

199, 2*), of which over $2 billion are still outstanding (R.

184, 3-4). About $250 million in principal amount of Texas

school district bonds were sold in 1971 alone (R. 200, Ex.

F ). Members of the SIA, a voluntary national organization

of more than 700 securities firms and banks, served as un

derwriters for the great majority of these bonds (R. 199,

1 -2 ) and intend to continue to underwrite Texas school

district bonds (R. 204, Masterson Aff., 2). Many SIA

members also hold outstanding Texas school district bonds

as investments (ibid.), and the four amici banks hold over

$100 million in principal amount of Texas school district

bonds (almost five per cent of the total outstanding) for

their own account and as trustees for various charitable,

testamentary, and other trusts.**

Any impairment of the continuing collectibility of the

property taxes levied to pay the Texas school district bonds

held by the amici banks and other SIA members would

adversely affect their value and their status as legal invest

ments for fiduciaries, and would jeopardize the market

ability of future issues of Texas school district bonds.***

Thus the interest of the amici banks and the SIA in the

continuing enforceability of outstanding and interim-

issued Texas school district bonds is immediate and

substantial.

* Citations in the form “ R. 199, 2” refer to page 2 of document 199

o f the record on appeal.

** R. 204, Roberts A ff., 1-2, Rogers Aff., 1, Lyne Aff., 1-2, Hazard

Aft., 1.

*** R. 204, Roberts A ff., 2, Rogers Aff., 2, Lyne Aff., 2, Hazard

Aft., 2.

4

The members of the SIA have a similarly direct and sub

stantial interest in outstanding school district bonds

throughout the nation, all of which would be affected by

this Court’s decision in this case. Approximately $50

billion of public school bonds were issued in the United

States during the 25 years 1946-1971, and at least 90%

of these bonds were underwritten and distributed by SIA

members (R. 204, Masterson Aff., 1). $3.9 billion of pub

lic school bonds were sold in 1970-1971 alone.* The national

total of public school bonds outstanding on June 30,

1970 was more than $31.5 billion.** It is estimated that

95% of these bonds have remaining maturities ranging

from one to twenty years, and 57% have remaining maturi

ties ranging from five to twenty years.*** The continuing

collectibility of the property taxes which support these

bonds will thus remain of vital importance for years to

come.

* U. S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Bond

Sales for Public School Purposes 1970-71 (D H E W Publication No

(O E ) 72-63), at 11 (1972).

** U. S. Bureau o f the Census, Governmental Finances in 1969-70

(Series GF-70, No. 5 ), at 28 (1971).

*** According to estimates based on SIA data for state and local gen

eral obligation bonds as a whole (which include virtually all public

school bonds), the distribution of the time remaining at December 31,

1971 until maturity of such bonds was as follows:

1-4 Y e a r s .......................... $39.4 Billion (37 .2% )

5-9 Y e a r s .......................... $31.3 Billion (29 .6% )

10-14 Y e a r s ...................... $17.3 Billion (16 .4% )

15-19 Y e a r s ...................... $11.9 Billion (11 .2% )

20 Years or M o r e ........... $ 5.9 Billion (5 .6% )

5

Statement

1. The Nature of Texas School District Bonds

Article 7, § 3 of the Texas Constitution authorizes the

Texas Legislature to establish school districts and to permit

them to levy and collect ad valorem property taxes. Pur

suant to this authorization, the Legislature has authorized

Texas school districts to issue negotiable coupon bonds “ for

the construction and equipment of school buildings in the

district and the purchase of the necessary sites therefor,”

provided that both the issuance of the bonds and the levying

of the property taxes necessary to pay them are authorized

by the voters of the district in a special bond and tax

election. Texas Educ. Code §§ 20.01, 20.04. Before such

bonds may be issued, they must be approved as properly

authorized by the Attorney General of Texas and registered

by the Comptroller of Public Accounts,

“ and after such approval and registration such

bonds shall be incontestable in any court, or other

forum, for any reason, and shall be valid and bind

ing obligations in accordance with their terms for all

purposes.” Texas Educ. Code § 20.06.

General bond market practice also conditions the sale

of school district bonds to investors upon the unqualified

approving opinion of recognized bond counsel (R. 199, 7-8).

Both the Attorney General of Texas and bond counsel

require as a condition of their approval a “ no-litigation

certificate” by the issuing school district that it knows of

no pending or threatened litigation in any manner ques

tioning the validity of the bonds or the levying of property

taxes to pay them (R. 199, 6-7, Ex. B ). The certificate of

the Comptroller of Public Accounts attesting the approval

6

of the Attorney General and, in most cases, the approving

opinion of bond counsel are set forth in full on the bonds

themselves (R. 199, Ex. A ).

Texas school district bonds are payable solely from ad

valorem taxes levied on property within the district. See

Texas Educ. Code § 20.01. A specific rate of property tax

is levied each year to pay each specific issue of bonds, and

the funds collected therefrom become trust funds for the

benefit of the bondholders and may not lawfully be expended

for any other purpose. Love v. City of Dallas, 120 Tex.

351, 367-68, 40 S.W.2d 20, 27 (1931); McPhail V. Tax

Collector, 280 S.W. 260, 265 (Tex. Civ. App. 1926). If the

bonds are not paid, the bondholders’ only remedy is by

mandamus to compel the school district to levy the specific

property tax to pay the principal and interest on the

defaulted bonds. City of Waco V. Mann, 133 Tex. 163, 174,

127 S.W.2d 879, 885 (1939). The property of a Texas

school district has been held not to be subject to execution

or garnishment. National Surety Cory. V. Friendswood hid.

School Dist., 433 S.W.2d 690, 694 (Tex. Sup. Ct. 1968).*

* The principle that an obligation o f a Texas school district may

not be enforced by execution or garnishment applies to all school dis

trict obligations, not merely to school district bonds. For this reason

the District Court’s Clarification of Original Opinion in the present

case protects any outstanding or interim “ contractual obligationi in

curred by a school district in Texas for public ^ o l purposes.

Rodriquez v. San Antonio Ind. School Dist., 337 F. Supp. 280, 2e

(\VD . Tex. 1971). The need to protect outstanding and interim-

issued school district bonds is especially acute, however, for two rea

sons- (1 ) such bonds, unlike other obligations, are negotiable instru

ments backed by an express pledge of property tax revenues whose

validity is certified by the Attorney General o f Texas and upon which

bond purchasers rely; and (2 ) such bonds are of much longer dura

tion than other contractual obligations o f school districts. Texas school

district bonds may have maturities o f up to forty years, Texas Educ.

Code § 20 01 while other contractual obligations are limited to shorter

periods. See; e.g., Texas Educ. Code §§ 12.29(a) (textbook adoption

7

Most public school bonds elsewhere in the nation are

likewise supported by local property taxes and other local

taxes * Thus an affirmance of the District Court without

making clear that outstanding and interim-issued bonds

will be protected would have severe repercussions not only

in Texas but throughout the country.

2. The District Court’s Clarification

of Original Opinion

On December 23, 1971 the three-judge District Court

issued its decision in the present case holding that the

present Texas system of financing public education denies

equal protection and enjoining (after a two-year stay) the

enforcement of Article 7, § 3 of the Texas Constitution,

the State constitutional basis for all Texas school district

property taxes. Rodriguez v. San Antonio Ind. School Dist.,

337 F. Supp. 280, 285-86 (W.D. Tex. 1971). The question

of the continuing enforceability of outstanding and interim-

issued Texas school district bonds had not been raised by

any party, and the District Court’s decision was silent on

this question. For this reason it had a devastating impact

upon Texas school district bonds.

contracts; six years), 13.102 (teachers’ probationary contracts; three

vears) 13.107 (teachers’ continuing contracts may be terminated at

end of any year “ because of necessary reduction of personnel ),

23 28fb l (c ) (employment contracts; three or five years), 23 ./o

(depository banks; two years).

* Putting aside revenue bonds, over 90% of the public school bonds

sold in 1970-1971 were sold by school districts and other local bodies.

See U. S. Department o f Health, Education, and Welfare, Bond Sales

for Public School Purposes 1970-71 (D H E W Publication No. (O )

72-631 at 6 14 (1972). Property taxes are estimated to comprise

97 to 98% of all local school tax revenues. Moore Local Nonproperty'

Tavcs tor Schools, in Johns, Alexander & Stollar, eds., Status and

Impact of Educational Finance Programs (National Educational Fi

nance Project, Volume 4 ) , at 209-10 (1971).

8

Neither the Attorney General of Texas nor bond counsel

for issuers were able to approve Texas school district bonds

issued after the decision (R. 199, 7-10). The sale of such

bonds halted abruptly (R. 199, 10), and only resumed

after the District Court’s Clarification of Original Opinion

was issued on January 26, 1972. The value of outstanding

Texas school district bonds fell immediately after the deci

sion (R. 199, 10). »

Defendants, joined by the SIA as amicus curiae and by

other amici, urged the District Court to clarify its decision

to specify that it was not intended to affect the continued

collectibility of property taxes levied to pay outstanding

and interim-issued bonds (R. 184,192, 199). The SIA took

no position on the merits of the District Court’s decision.

The SIA explained that in order to safeguard the value

and marketability of outstanding and interim-issued bonds

it was necessary to insure the collectibility of property

taxes to be levied to pay such bonds after the ultimate

disposition of the action (R. 199, 10-11). The District

Court’s Clarification of Original Opinion dated January 26,

1972 expressly insured such continuing collectibility.

Rodriguez v. San Antonio bid. School Dist., 337 F. Supp.

280, 286 (W.D. Tex. 1971).

The purpose of the present brief is to urge this Court,

if it should affirm the District Court, to make clear that

the District Court acted rightly in issuing its Clarification

of Original Opinion to protect outstanding and interim-

issued Texas school district bonds.

3. Judicial Protection of Outstanding and Interim-

Issued Bonds in Other Jurisdictions

All of the courts which have held that the present system

of financing public education denies equal protection have

assured bond investors that this holding does not under

9

mine the enforceability of outstanding and interim-issued

school district bonds. This assurance has taken diverse

forms, but in all three cases which have gone to final

judgment— the present case and the cases in Arizona and

New Jersey— it has taken the form of an express provision

in the final judgment safeguarding the continuing collecti

bility of property taxes levied to pay outstanding and

interim-issued bonds.

California. On August 30, 1971 the California Supreme

Court held that the present California system of financing

public education denies equal protection under the Federal

and State Constitutions. Serrano v. Priest, 5 Cal. 3d 584,

487 P.2d 1241, 96 Cal. Rptr. 601 (1971). There was

widespread concern that the Serrano decision might be

construed as affecting outstanding and interim-issued

bonds, and many school bond issues across the country

were withdrawn or postponed indefinitely.*

On October 21, 1971, in response to this concern, the

California court issued a Modification of Opinion adding

the following paragraph to its original opinion:

“ In sum, we find the allegations of plaintiffs’

complaint legally sufficient and we return the cause

to the trial court for further proceedings. We

emphasize, that our decision is not a final judgment

on the merits. We deem it appropriate to point out

for the benefit of the trial court on remand (see

Code Civ. Proc. § 43) that if, after further pro

ceedings, that Court should enter final judgment

determining that the existing system of public

school financing is unconstitutional and invalidat

ing said system in whole or in part, it may properly

* E.g., American Banker, Nov. 11, 1971, p. 1; Daily Bond Buyer,

Nov. 15, 1971, p. 1.

10

provide for the enforcement of the judgment in

such a way as to permit an orderly transition from I

an unconstitutional to a constitutional system of ■

school financing. As in the cases of school desegre- 1

gation (see Brown v. Board of Education (1955)

349 U.S. 294) and legislative reapportionment (see

Silver v. Brown (1965) 63 Cal.2d 270, 281), a

determination that an existing plan of govern

mental operation denies equal protection does not

necessarily require invalidation of past acts under

taken pursuant to that plan or an immediate imple

mentation of a constitutionally valid substitute.

Obviously, any judgment invalidating the existing

system of public school financing should make clear

that the existing system is to remain operable until

an appropriate new system, which is not violative

of equal protection of the laws, can be put into

effect.” 5 Cal. 3d at 618, 487 P.2d at 1266, 96

Cal. Rptr. at 626.

Minnesota. In a Memorandum and Order filed on Octo-

* 12, 1971 the United States District Court for the Dis-

ct of Minnesota denied defendants’ motion for summary

Igment and held that the present system of financing

blic education in Minnesota violates the Equal Protection

luse. Van Dusartz v. Hatfield, 334 F. Supp. 870 (D.

nn. 1971). The court made clear that it did not intend

holding to have any immediate effect upon school financ- f

;; it did not direct any affirmative relief, but deferred to

action of the Minnesota Legislature. 334 F. Supp. *

377.

Wyoming. On December 14, 1971 the Supreme Court of

roming adopted the Serrano principle. Sweetwater

mty Planning Committee v. Hinkle, 491 P.2d 1234

yo. 1971), 493 P.2d 1050 (Wyo. 1972). The Wyoming

rt stated, however, that “ [n]o invidious discrimination

11

will be involved if bonds are voted by any school district for

capital improvements, and if special levies are made within

the district to retire such bonds.” 491 P.2d at 1238. Since

school bonds may be issued in Wyoming only for capital

improvements, see Wyo. Const., Art. 16, § 5 ; Wyo. Stat.

§ 21.1-253, this statement obviated any question as to the

continuing validity of Wyoming school bonds.

New Hampshire. The New Hampshire Supreme Court

held on December 23, 1971 that a city council was required

to furnish the board of education with funds required to

meet state minimum standards. Laconia Bd. of Educ. v.

City of Laconia, 285 A.2d 793 (N.H. 1971). It refused

to consider a belated argument that such a holding would

violate the Serrano principle, in part on the ground that

Serrano was not made retroactive:

“ Thirdly, it is doubtful that any consideration of

this contention would have any retroactive effect

whatever result was reached. See October 2 1 , 1971

modification of opinion in Serrano v. Priest supra

reported in 40 U.S.L.W. 2339 where it was stated

that the ‘existing system of school financing is to

remain in effect until it has been found unconstitu

tional and replaced by an appropriate new system’.”

285 A.2d at 796-97.

New Jersey. On January 19, 1972 the New Jersey Su

perior Court held that the present system of financing

public education in New Jersey violates the Equal Protec

tion Clauses of the Federal and State Constitutions and

the Education Clause of the State Constitution. Robinson

V. Cahill, 118 N.J. Super. 223, 287 A.2d 187 (1972). It

made clear, however, that

“ this declaration shall operate prospectively only

and shall not prevent the continued operation of the

school system and existing tax laws and all actions

12

taken thereunder. This declaration shall not invali

date past or future obligations (such as school

bonds, anticipation notes, etc.) incurred under the

provisions of existing school laws and tax laws.

Said laws shall continue in effect unless and until

specific operations under them are enjoined by the

court.” 118 N.J. Super, at 280, 287 A.2d at 217.*

'ZOna. On June 1, 1972 the Arizona Superior Court

sd a declaratory judgment that the present Arizona

ti of financing public education violates the Federal

State Equal Protection Clauses. Hollins V. Shofstall,

Super. Ct., Maricopa County, No. C-253652, June 1,

On June 6, 1972 the court issued a Supplemental

orandum making clear that it intended to protect the

nued enforceability of outstanding and interim-issued

s throughout their entire life:

“ Notwithstanding anything to the contrary stated

in the memorandum and order of June 1, 1972, it is

the intention of the court that general obligation

bonds heretofore or hereafter issued by school dis

tricts shall enjoy full and complete security afforded

by the applicable bond-enabling statute, and the

bondholder shall have recourse to the levy of an ad

valorem tax upon all taxable property within the

district to compel the payment of the principal of

and interest on such bonds, throughout their entire

life and as the same shall become due, in the event

that funds for the payment of such bonds are not

lawfully available from other sources.”

Paragraph 7 o f the Judgment entered on February 4, 1972 in

insonv. Cahill provided even more explicitly that nothing herein

1 be deemed to limit, impair or affect any bonds heretofore or here-

r issued or authorized for public school purposes, or any notes or

t obligations at any time authorized or issued in anticipation o f

i bonds, or any taxes levied or required to be levied with respect

ny such bonds, notes or other obligations . . . .

Summary of Argument

1 . As no appeal has been taken from the portion of the

District Court’s judgment which protects outstanding and

interim-issued bonds, it is therefore not actually before this

Court for review. Nevertheless, if the Court affirms the

decision of the District Court, we respectfully submit that

the Court should make clear that the decision will not

affect outstanding and interim-issued bonds, in order to

prevent the disruption of school bond markets throughout

the nation which might otherwise result.

2 This Court’s decisions, especially Cipriano v. City of

Houma, 395 U.S. 701, 706 (1969) (per curiam), and City

of Phoenix V. Kolodziejski, 399 U.S. 204, 213-15 (1970),

which are almost exactly in point, establish that the District

Court’s decision should not be retrospectively applied. Ret

rospective application is wholly unnecessary to achieve the

purpose of the District Court’s holding, and would be strik

ingly unjust in light of bondholders’ reliance upon express

legal opinions and representations by the issuers that the

bonds are supported by valid and enforceable property

taxes.

3. Retrospective application of the District Court s hold

ing would also offend the constitutional values embodied in

the Contract Clause and the Due Process Clause. The Equal

Protection Clause should not be unnecessarily applied in a

manner which brings it into conflict with these coordinate

constitutional values.

14

ARGUM ENT

I

This Court Should Reaffirm the District Court’s

Protection of Outstanding and Interim-Issued

Bonds

The District Court’s Clarification of Original Opinion

issued on January 26, 1972 stated that its decision and

order of December 23, l\)ll in no way affected the continu

ing collectibility of property taxes levied to pay outstanding

bonds and interim-issued bonds issued and delivered before

December 23, 1973, by which time the District Court anti

cipated that the present system of financing public educa

tion in Texas would be replaced by a constitutional system.*

Rodriguez v. San Antonio Ind. School Dist., 337 F. Supp.

280, 285-86 (W.D. Tex. 1971).

Defendants have not appealed from this portion of the

District Court’s order, and plaintiffs have taken no ap

peal.** It follows that the portion of the District Court’s

order which protects outstanding and interim-issued bonds

may not be disturbed in this Court. See, e.g., Swarb v.

Lennox, 405 U.S. 191, 201-03 (1972); Morley Construction

Co. v. Maryland Cos. Co., 300 U.S. 185, 191-92 (1937).

* W e have spoken in this brief of the need to protect interim-issued

bonds issued and delivered prior to the ultimate disposition o f this

action, rather than interim-issued bonds issued and delivered before

December 23, 1973, for two reasons: (1 ) the necessary transitional

period, if the District Court’s holding is affirmed, will differ from state

to state and may be longer or shorter than two years; and (2 ) while

the District Court’s judgment requires the State of Texas to act before

December 23, 1973, final judicial approval of a new system o f public

school financing might not take place until a later date.

** Indeed, plaintiffs represented to the District Court, in order to

induce it to deny the motion made by the SIA and the four amici

banks for permission to intervene, that they would not seek to over

turn the District Court’s clarification insuring the continuing enforce

ability of outstanding and interim-issued bonds (R . 207, 28-29).

15

We nonetheless respectfully urge the Court, if it should

affirm the decision of the District Court, to make clear that

its decision should only be applied prospectively from the

ultimate determination of the action, and should not affect

the continued collectibility of property taxes to be levied to

pay outstanding and interim-issued school district bonds.

Otherwise, especially in view of the numerous similar cases

now pending in many jurisdictions,* this Court’s decision

might have the same sharply disruptive effect upon school

bond markets throughout the nation as the initial decision

of the District Court had in Texas, and would draw into

question the rights of holders of more than $31.5 billion in

outstanding public school bonds. Such a disruptive shock,

even if later corrected, might permanently lessen public

confidence in the security of public school bonds.**

II

This Court’s Decisions Establish That the

District Court’s Holding Should Not Be

Applied Retrospectively

The District Court’s holding that its decision should be

applied only prospectively is squarely supported by two

decisions of this Court, also involving local government

* A partial summary o f these cases, listing 24 cases in 15 states,

is given in Comment, The Evolution o f Equal Protection: Education,

Municipal Services, and Wealth, 7 Harv. Civ. Rights— Civ. Lib. L.

Rev. 103, 200-13 (1972).

** It is to avoid such adverse consequences that the courts which

have held that existing school financing systems deny equal protection

have assured bond investors that this holding does not affect outstand

ing and interim-issued bonds (see pp. 8-12 supra). Similarly, a New

York trial court declined to anticipate the decision of this Court on the

basic equal protection issue in order to avoid “ placing the sword of

Damocles over school bond financing in this State for the next several

years.” Spano v. Board of Educ., 68 Misc. 2d 804, 808, 328 N.Y.S.2d

229, 234 (Sup. Ct. Westchester County 1972).

X \ J

bonds and the Equal Protection Clause, which are almost

exactly in point. In Cipriano v. City of Houma, 395 U.S.

701, 706 (1969) (per curiam), this Court ruled that the

franchise in a municipal revenue bond election cannot con

stitutionally be limited to property taxpayers, but held that

this decision should be given prospective effect only:

“ Significant hardships would be imposed on cities,

bondholders, and others connected with municipal

utilities if our decision today were given full retro

active effect. Where a decision of this Court could

produce substantial inequitable results if applied

retroactively, there is ample basis for avoiding the

‘injustice or hardship’ by a holding of non-retro

activity. Great Northern R. Co. v. Sunburst Oil &

Refining Co., 287 U.S. 358, 364 (1932). See Chicot

County Drainage Dist. v. Baxter State Bank, 308

U.S. 371 (1940). Cf. Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S.

618 (1965). Therefore, we will apply our decision

in this case prospectively.”

Just as in Cipriano, a decision retrospectively wiping out

the sole security for Texas school district bonds would im

pose “ significant hardships” and “produce substantial in

equitable results” . As in Cipriano, such an injustice should

be avoided by a holding of nonretroactivity.

In City of Phoenix v. Kolodziejski, 399 U.S. 204, 213-15

(1970), this Court extended Cipriano to voting on muni

cipal general obligation bonds, and likewise held that its

decision should be given prospective effect only. The Dis

trict Court’s holding of nonretroactivity in the present case

is identical to Cipriano and Kolodziejski, except that the

District Court made its decision prospective from Decem

ber 23, 1973, by which time the District Court anticipated

that a new system of financing public education would be

instituted. This difference is a practical necessity because

the pressing capital needs of school districts must continue

to be met by the issuance of bonds under the present system

until another system has been finally approved by the Leg

islature and the Courts.

This Court recently summarized the three key factors

bearing on the question whether a new decision should be

applied retroactively in Chevron Oil Co. v. Huson, 404 U.S.

97, 106-07 (1971) : (1 ) whether the effect of the decision

is to “ establish a new principle of law, either by overruling

clear past precedent on which litigants may have relied,

. or by deciding an issue of first impression whose reso

lution was not clearly foreshadowed” ; (2 ) whether retro

active application of the decision would further or retard

its purpose; and (3 ) whether retroactive application would

produce substantial inequitable results. All three of these

factors argue strongly against retrospective application of

the District Court’s decision in the present case.

Although, as already stated, the SIA and the amici banks

do not wish to and do not take any position with respect to

the merits of the present appeal, there can be no question

that a decision by this Court affirming the judgment of the

District Court would “ establish a new principle of law” .

So far as we are aware, no action challenging the validity

of existing systems of financing public education under the

Equal Protection Clause was ever brought until 1968.

When such cases were brought, this Court twice sustained

existing systems against equal protection attacks. See Mc-

Innis v. Shapiro, 293 F. Supp. 327 (N.D. 111. 1968), aff’d

mem. sub nom. Mclnnis v. Ogilvie, 394 U.S. 322 (1969);

Burruss V. Wilkerson, 310 F. Supp. 572 (W.D. Va. 1969),

aff’d mem., 397 U.S. 44 (1970). We recognize that the

18

District Court held Mclnnis and Burruss to be distinguish

able from its decision, Rodriguez v. San Antonio Ind.

School Dist., 337 F. Supp. 280, 283-84 (W.D. Tex. 1971),

and take no position with respect to the validity of the dis

tinction on the merits; but we respectfully submit that,

even accepting the distinction, the District Court’s deci

sion was not “ clearly foreshadowed” by any decision of

this Court.

The second factor recognized in Chevron Oil Co. v.

Huson is the purpose of the new decision. See also Desist

v. United States, 394 U.S. 244, 249-50 (1969); Linklettery.

Walker, 381 U.S. 618, 636-37 (1965). The purpose of the

District Court’s holding— removing disparities in educa

tional expenditures arising from disparities in taxable

wealth— does not require the elimination of the property

taxes needed to pay outstanding and interim-issued bonds.

It merely requires that, without altering school districts’

duty to levy property taxes to pay outstanding and interim-

issued bonds as they have solemnly contracted to do, the

State adjust the allocation of remaining State and school

district educational funds to insure that any constitution

ally mandated balance of educational expenditures is

achieved.’ The thrust of Serrano and the decisions that

have followed it, including the decision of the District

Court, is to condemn the end result of the school financing

system, not any specific component of the collective source

of funds.

* Some courts have held that the Serrano principle serves the addi

tional purpose o f equalizing the property tax burden on taxpayers in

different school districts. See, e.g., Robinson v. Cahill, 118 N.T.

Super. 223, 276-80, 287 A .2d 187, 215-16 (1972). This purpose can

likewise be met by statewide redistribution of educational funds with

out disturbing the property tax security for outstanding and interim-

issued bonds.

19

Finally, it is plain that retrospective application of the

District Court’s decision would produce substantial inequit

able results, the third factor identified in Chevron Oil Co.

v. Huson. Investors acquired outstanding Texas school

district bonds in reliance upon express representations by

the issuers and legal opinions of bond counsel and the

Attorney General of Texas that the bonds were valid obli

gations supported by an enforceable duty to levy ad

valorem taxes on property within the issuing school dis

trict. These opinions, indeed, were commonly printed on

the face of the bonds themselves, which are fully negotiable.

Without these opinions, the bonds could not have been

sold. In reliance upon these opinions, the bonds have been

accepted as investments not only by numerous individuals

but also by the amici banks and many other institutions for

their own account and as trustees for charitable, testa

mentary, and other trusts. Under these circumstances, to

apply the District Court’s decision retroactively so as to

wipe out the property tax security for the bonds would

be strikingly unjust. The District Court correctly made

clear that it intended no such result.*

* This Court recognized the injustice o f retroactively invalidating

bonds as early as Gclpckc v. City of Dubuque, 68 U.S. (1 W all.) 175,

205-07 (1863), which held that bonds whose validity had been upheld

by the highest State court would be recognized in a federal court de

spite an overruling decision by the State court. Although the precise

holding of Gelpcke v. City o f Dubuque has probably been overruled

by Eric R.R. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64, 69 n.l (1938), its underlying

principle was discussed with approval in Linklcttcr v. Walker, 381

U.S. 618, 624-25 (1965).

20

III

Retrospective Application of the District Court’s

Holding Would Offend the Principles Embodied

in the Contract Clause and the Due Process Clause

Retrospective application of the District Court’s holding

outstanding and interim-issued bonds would contravene

i principle of governmental good faith embodied in the

intract Clause. This Court has long held that a State

iy not, under the Contract Clause, withdraw a power to

x which has been made the basis for bonds which are still

tstanding. E.g., Von Hoffman V. City of Quincy, 71 U.S.

[ Wall.) 535, 554-55 (1866). Under this principle the

istrict Court’s holding could not be utilized as a ground

r legislative repeal of the property taxes supporting

hool district bonds, because such invalidation is not neces-

try to achieve the purpose of the District Court’s holding

nd the decisions of this Court establish that governmental

oligations may not be repudiated unless “ the extent of the

gpudiation is only that which is reasonably necessary to

ffectuate a valid objective” . Slawson, Constitutional and

„egislative Considerations in Retroactive Lawmaking, 48

Jalif. L. Rev. 216, 244 (1960).

Retrospective application of the District Court’s holding

lould also run counter to the values embodied m the Due

Process Clause. It would drastically change the nature of

;he bondholders’ contracts because of a constitutional prob-

em which they did not cause and from which they derived

no benefit. If it were sought to be legislatively imposed, such

an imposition of a burden upon a group which did not cause

or benefit from the underlying problem would deny due

process of law. C/., e.g., Atchison, T. <& S.F. Ry. v. Public

um. ( W * 346 U.S. 346. 352-53 (1953); N e v il le , C.

£ S.L. Ry. v. Walters, 294 U.S. 405, 428-32 (1935).

The principles embodied in the Contract Clause and the

Due Process Clause are of coordinate dignity with the Pim-

ciple^Tequality embodied in the Equal Protection Clause

Wherever possible, such coordinate constitutional pnn«P

lo u ld be accommodated, as this Court has observed

example, with respect to the Establishment and Free Ex

cise Clauses of the First Amendment. E.g., Walz V. T

Z n m ’n, 397 U.S. 664, 668-72 (1970). This

strongly supports the conclusion of the District Couit that

its decision should not be retrospectively applied.

22

CONCLUSION

For the reasons given above, Republic National Bank of

Dallas, First City National Bank of Houston, Mercantile

National Bank at Dallas, Bank of Texas, and Securities

Industry Association, Inc., respectfully urge the Court, if

it should affirm the decision of the District Court, to make

clear that the District Court correctly held that its decision

should in no way affect the continuing collectibility of prop

erty taxes to be levied to pay the principal and interest on

Texas school district bonds outstanding at the time of the

District Court’s decision or authorized and issued prior to

the ultimate disposition of this action.

Dated: July 21, 1972

Respectfully submitted,

Law rence E. W alsh

1 Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, New York 10005

212 422-3400

R ichard B. Sm ith

Gu y M. Struve

Of Counsel

V ictor W . Bouldin

2100 First City National

Bank Building

Houston, Texas 77002

713 225-2411

Clifford W . Y oungblood

Of Counsel

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

IN TH E

Supreme Court of Ujc ulntteb State#

O cto b e r T erm , 1971

No. 71-1332

SAN A N T O N IO INDEPENDENT SCHO OL D IS

T R IC T , et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

D E M E T R IO P. R O D R IG U E Z, et al.,

r r Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM TIIF. UNITED STATES D IST R IC T C O U R T

FOR THE WESTERN D ISTR ICT OF TEXAS

M ill F or AMICI C U R IA E : RICH ARD M. CLO W E S, SU PER

INTENDENT OE SCHOOLS OF TH E CO U N TY OF LOS

ANOEI.ES, H ARO LD J. O ST LY , T A X CO LLECTO R AND

T R E A SU R E R OE TH E COUNTY OF LOS ANG ELES; EL

S E (; UNDO UNI I'I ED SCHO OL D IS T R IC T ; GLENDAI.E

UNIFIED SCH O O L D IS T R IC T ; SAN M ARINO UNIFIED

SC H O O L D IS T R IC T ; LONG REACH UNIFIED SCH O O L

D IS T R IC T ; SO U TH R A Y UNION IUGII SCH O O L D IS

T R IC T : R E VE K LY IIIEI.S UNIFIED SCH O O L D IS T R IC T ;

AND SAN TA MONICA UNIFIED SCH O O L D IS T R IC T , A LL

O F LO S ANGELES COU NTY.

JOHN D. MA1IARG,

County Con nr el .

JAMES \V. BRIGGS,

Division Chief, Schools Division,

D O N O V A N M. M AIN ,

Deputy Coun.y Counsel

618 Hall o) Administration

500 West ’I cinple Street

Los Angeles, California 90012

(213) 625-3611, Ext. 65643

Attorneys for Amici Curiae.

W i e r c H N p u l N T l N d CO M PAN Y. WHITTIKA---- O X I O W » - l 7 i *

TOPICAL INDEX

Interests oi‘ Am ici .............. ............................ ..... ............. 1

Statem ent.............................................. 3

Summary o f A rgu m en t.......................... ..... ........... _........ 6

Argument .................................. 10

I . The District Court Erred In A pplying the

“ Compelling Interest” Test Rather Than A

Less Onerous Standard o f Review In Testing

the Validity o f the Texas School Financing

Law's ............................................................................ 10

Page

A . The District Court, Tn the Course o f U n

critically R elying Upon Serrano, E rron

eously Concluded That the “ Necessary to

Prom ote A Compelling State Interest”

Test Should P e A p p lie d ................................. 10

B. In Determining the Standard o f Review

to he Applied In an “ Equal P rotection ”

Case, all Pertinent Factors Should Be Con

sidered ........................................................ ........ 16

C. Consideration o f all Pertinent Factors In

volved in This Case Requires That A Less

Onerous Standard o f Review' Should Be

Applied In Testing the V alidity o f the

Complex Texas School Financing Laws

Under the Equal Protection Clause .... .....21

11 Index

Page

1 . The Individual Interests Involved ...... 22

2. The Actual Character o f the Alleged

Classification .............................................. 27

3. Societal or Governmental Interests

Supporting or A ffected by the Texas

School Finance System ............................. 32

4. Consequences o f Frustrating Legisla

tive and Congressional Attemps to Pro- ,

mote Educational Opportunities .....-... 37

5. The Ability o f the Courts to Fashion

and Enforce Fair and Appropriate

Remedies ..................... 40

D. Conclusion ............................ 41

I I . The Texas School Financing System is Valid

Under Any Fairly Applicable Standard o f

Review ....................................................................... 42

I I I . The -Monumental Task o f More Fairly A llo

cating Financial Resources to School Districts

Is Properly A Function to be Exercised B y

the State Legislature and the Congress, and

Not B y the Courts ............................. .........— ... 58

D ifferences in Status Q u o .........................................-... 5S

Allowing for Differences in Educational N eed s.... . 59

Allowing for Differences in C osts ............................... 61

Allowing for Federal Grants and Private G if t s ....... 61

Index in

Allowing for Differential Services Rendered by

State and Intermediate Educational Units ........ 62

Allowing for Innovation on “ Pilot P ro je c t” Basis... 63

IV . The .Judgment I b low Should Be Reversed

Because the Order Granting the Injunction

Lacks Specificity and Fails to Describe in

Reasonable Detail the Acts Sought to be R e

strained and Because o f Absence oi .. adispen-

Page

sible Dailies ........................ ................. 72

Lack o f Specificity ..................... ... ............. 72

Lack o f Indispensable Parties .. _______ __ 77

Conclusion ...................................... ... ............. 79

TAliLE OF CASES AND AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases

Askew v. Hargrave, 401 II.S. 476 91 S.Ct. 856, 28

L.Ed.2d 196 (1971) ............................................... 26, 27

Board o f Ed. o f Inch Sell. Dist., 20, Muskogee v.

Oklahoma, 409 F.2d 665 (1969) ................ 14, 26, 49

Brown v. Bd., 347 U.S. 483, 98 L.Ed. 873, 74 S.Ct.

686 (1954) ................................................. .............24, 78

Bullock v. Carter, 405 U.S. 134, 31 L .E d.2d 92,......,

92 S.Ct. 849 (1972) .............................. .........19, 20, 25

Burruss v. W ilkerson, 310 F.Supp. 572 (W .D . Va.

1969) ................................................................... 26, 55, 63

Carmichael v. Southern Coal Co., 301 U.S. 495, 81

L.Ed. 1245, 57 S.Ct. 868 (1936) 26

r

iv Index

Carmichael v. Southern Coal Co., 301 U.S. 195, 81

L.Ed. 1245 (1936) ................................................. .... 14

. Dandridge v. Williams, 397 U.S. 471, 25 L.Ed.2d

491, 90 S.Ct. 1153 (1970) .............................19, 25, 35

Douglas v. California,,372 U.S. 353, 9 L.Ed.2d 811,

83 S.Ct. 814 (19031 ......................................... 19, 27. 29

Dunn v. Hlumstein, -101 U .S........ , 31 L.Ud.2d 274,

284, 92 S.Ct. 995 (1972) ......................................17, 19

General Am. Tank Car Corp. v. Day, 270 U.S. 367,

70 L.Ed. 635, 46 S.Ct. 234 (1926) ................. ........ 49

G riffin v. County School 13d., 377 U.S. 218, 84 S.Ct.

1226, 12 L.Ed. 2d 256 (1964) ............................ 24, 31

G riffin v. Illinois. 351 U.S. 12 , .100 L.Ed. 891, 76

S.Ct. 5S5 (1956) ..................................... 19, 24, 27, 29

Gunn v. University Committee to End. the W ar in

Vietnam, 399 U.S. 383, 26 L.Ed. 684, 90 S.Ct.

Tage

2012 (1970) .................................................................. 73

Hal-grave v. Kirk, 313 F . Supp. 944 (1970) .............. 26

H argrave v. M cKinney, 313 F.2d 320, 324 (5th Cir.

1969) ............................................................... .......-....... 27

H arper v. State Hoard o f Elections, 383 U.S. 663,

16 Jj.Ed.2d 109, 86 S.Ct. 1079 (1966)... 19, 24. 27, 29

Hess v. Dewey, 348 U.S. 835 (1954) ...................... 14, 49

Hess v. Mullaney (9th Cir. 1954)

213 F.2d 635 ......................... .......................... 14, 26, 49

Janies v. Strange, 40 Tj.W . 4711, 4714 ...................... 18

James v. Valtierra, 402 U.S. 137, 28 L .Ed.2d 678,

91 S.Ct. 1331 (1971) .................. 25, 29, 31, 33, 41, 54

Jefferson v. H ackn ey,......U .S ......., 32 Jj.Ed. 2d 285,

92 S.Ct. ...... (1972) ............... .................. ........ 25, 35, 46

Index v

Jefferson v. Hackney, 40 LAV. 4585 (1972) ............ 19

Madden v. Kentucky, 309 U.S. 83, 84 L.Ed. 590,

(1939) .............................................................................. 57

McDonald v. Hoard o f Elections Commissioners,

391, U.S. 802, 22 L. Ld.2d 739, 89 S.Ct. 1404

(1969) ..........................................................-.... -....-19, 27

M elunis v. Ogilvie, 394 E.S. 322 (1969) ..............26, 55

M clnnis v. Shapiro, 293 E.Supp. 327 (N .D . 111.

1968) ............................................. .......... -......... 26, 55, 68

Metropolis Theatre Co. v. City o f Chicago, 228 U.S.

61, 57 L.Ed. 730 (1930) .................................... -....... 55

National Labor Relations Hoard v. Hell Oil & Gas

Co. (C.C.A. 5th 1938) 98 Fed. 2d 405 .................. 76

Pierce v. Society o f Sisters, 268 U.S. 510, 269 L.Ed.

1070, 45 S.Ct. 571 (1925) .............................24, 36, 48

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 81 S.Ct. 1362, 12

L.Ed.2d 506 (1964) ................... ..........................25, 31

Rodriguez v. San Antonio Independent School D is

trict, 337 E. Supp, 280 (1972) ................................. 2

Salsburg v. Maryland, 346 U.S. 545, 98 L.Ed. 281,

74 S.Ct. 280 (1953) ........................ t ............... 30, 31

San Ansehno Police O fficers As., et al v. City o f

San Anselmo, et al. (M arin Co., Cal. No. 61302)... 4

Sehilb v. Kuobal, 40 LA V 7107 (1971) ......... ............. 18

Serrano v. Priest, 5 Cal. 3d 584, 487 P.2d 1241,

96 Cal. Rptr. 601....2, 3, 6,10. 11, 16, 2:), 27, 47, 50, 57 '

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479, 5 L.Ed.2d 231, 81

S.Ct. 247 (1960) .......................................................... 17

Swift Company v. United States, 196 U.S. 375, 49

L.Ed. 518, 25 S.Ct. 276 (1904)

Page

76

VI Index

Tliaxton v. Vaughan (4th Cir., 19(i3) 321 F 2d 474 ^

473 .................................. ’

W atson v. Buck, 313 U.S. 387 ̂ 85 1446...61 ?<

S.Ct. 962, 136 A LR 1426................................. ’ 75

V lllnnnson v Lee Optical Co., 348 U.S 483 99

L.Ed. 563, 75 S.Ct. 4 6 1 ........................ ’ 35

W isconsin v. Y o d e r ,......U .S....... , 32 L.Ed." 2d 15 "93

w >Sf ; .....T (1972) ........................1 8 > -R 36, 37/ 48, 70

V right v. Council o f the City o f Emporia, 40 Law

W eek 4806 ...... ................................................. ....-... 49

Authorities

Statutes

California Education Code,

§§894-894.4 ............. ..................

§§6450 ....... _..........._..............

§§6490-6493 ..... ...... ............ ............ ............ ............

§§6499-6499.9 ............. .............. •

§§6750-6753 ............. ............

§§6801-6822 ........... ....................

§§6870-6870.6 .............

§§6901-6920 .......

§6920 ........................ .....................

§§7001-7028 ................................

§17300 ......................

§§17651 ..............................

§§17901-17902 .................... ........

§§20800 ........................................

§§26401-26404 ...........................

Page

.............. 47

.................. 46

................. 46

..... ........... 46

.......... ...... 47

... -............ 47

................. 47

............ ..... 47

................. 47

................. 47

-...32, 45, 51

................. 43

............ 48

...... ......32, 43

...... - ....... 47

Index vii

Page

Federal Rules o f Civil Procedure

Rule 65(d) ....... ...... .............................9, 7^ 7^ 7^ 77

Hawaii Rev. Laws

§ § 2 9 6 -2 , 2 9 8 -2 (1968) ....................................... 2

Texas Education Code,

§§16.01 et set]............

^ 2u m .................................... A z r z r . . . ^ , «

§§16.74-16.78 ...................... .............

28 U.S.C. §1253 ................................................. ............ 74

Legislative Materials

California Assembly Bill 1283 (1972) ..........65 A pp. B

California Senate Bill 1302 (1972) .............. ;j7> App C

Texts

Alternative Programs f o r Financing Education,

Vol. 5, The National Education Finance Project

(1971> ............................. ............................. -.................. 64

Averch, Pincus, et ah, H ow E ffective is Schooling '

(1972) ......................................................... .........._ 23

Brest, Book Review, 23 Stanford

I,R ev . 591 (1971) ................................................. 49, 56

Butts & Cremin, A History o f Education in Ameri- ’

can Culture (1 9 5 3 )....................................... 3?

California School Boards July/A ugust 1972 .......49

Index

Coleman Report, Equality o f Educational O ppor-"8 6 '

tunity (1<)(>6) ................................................... 23 2g

Coons, Chine i l l , Sugarman, Private W ealth and

I uhlie J'-ducation (iu 7 0 )... 4, 5, 24, 28, 4J, 10-71, 78

Cremm. '1 lie Transformation o f the School (l<j(jl).„ 27

Garner, Excellence: Gan We Be Equal and Excel- *

lent Too M Phil) ...... ................. ................. 7()

Goldstein, Interdistrict Inequality in School F i

nancing: A Critical Analysis o f Serrano v.

Priest and Its Progeny, 120 Univ. o f Penn L 11

504 (1[r7L>) ..... ^ Cl, 14, 21, 2(5, 27, 28 (A pp. A )

Kurland, Equal Educational Opportunity: The

Limits o f Constitutional Jurisprudence Undc-

fil,cd (lyGS> ............................... ......................66-67, 70

Lee, An Introduction to Education in Modern

America ........................ ...................... 33

Mort, Reusser, Policy, Public School Finance

• '.............................................................. 5, 34, 51

Hosteller & Moynihan, “ A Pathbreaking- R eport”

in On Equality o f Ed. O pportunity............. . 23

Strayer and Haig, Financing o f Education in the

State o f New Y ork (1923) ................... ................. __ 5

viii

IN TH E

Supreme Court o£ tlje Cuiteb States

O rloh er T erm , 1971

No. 71-1332

SAN A N TO N IO INDEPENDENT SCHO OL D IS

T R IC T , ct al.,

Appellants,

vs.

D E M E TRIO P. RO D RIG U EZ, ut al.,

Appellees.

O X APPEA. FROM TIIK lA T IE I) STATES IJUS I RICJT C O U R T

FOR 11 IT WESTERN D ISTR ICT OF TEXAS

B R IE F OF AMICI GURIAE: RICHARD M. ( LOWES. SU P ER .

INTENDENT OF SCHOOLS OF I HE COUNTY OF I OS

a n g e l k s , HAROLD .1. o s t l y , t \ \ COI M-CTOU w n

T O K A S..BK K 0 1 - T in : , III .N I V « ! ; ? : ! J L T f

i l ;N ,n i !) S ( : ,I ( , ( ) I - D IS T R IC T ; GLENDALE

UNIFIED SCHOOL D IS TR IC T; SYS MARINO LM E IE D

SCIKHIL D IS T R IC T ; LONE REACH UNIFIED SCHO OL

SOlJTH RAY UNION HIGH SCHOOI DIS-

,,,l ;V ,-RI.Y HILLS UNIFIED SCHOOL D IS TR IC T-

O F S<:,,O O L D ,S T R ,C T ’ A Li:

INTERESTS OF AMICI

■ Amici Curiae are ( ! ) the County Superintendent

ot Schools and t h e Treasurer-Tax Collector o f the

County o f Eos Angeles who are charged with adminis

tering certain aspects o f the California public school

financing system as it affects local school government

m Los Angeles County, and (2 ) several school dis

tricts in the County o f Los Angeles. Am ici are spon-

— 2—

so m l b-v Jolm T)- M ilia r - County Counsel o f Los An-

- clcs Connty, their authorized law officer. Amici, with

the exception of one o f the school districts, are all

parties defendant (the school districts by way o f in-

ten ention) in the case o f Serrano v. Priest (Los An

g le s Superior Court Xo. C938254) which is now pro

ceeding to trial in a California Superior Court, upon

remand from the California Supreme Court. See Ser

rano v. Priest, 5 Cal.3d 584, -187 P.2d 12-11 .% Cal

R ptr.601.

I]i the action presently before this Court, the court

below cited the opinion o f the California Supreme

Court in Serrano r. Priest, supra (1971), in support

o f its conclusion that Appellees are deprived of equal

protection o f the laws under the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Lnited States Constitution by the opera

tion o f the Texas public school financing system. Pod-

nrjuez r. San Antonio Independent School District,

337 F.Supp. 280, 2S1 (n. 1) (1972).

The school districts appearing as amici are charged

with the operation o f public schools within Los

Angeles County, all o f which would be adversely af

fected to a serious degree by application o f the rule

u iged In Appellees and adopted by the court below.

Ih e rl exas public school financing system is substan

tially similar to the system o f financing public schools

in California.1

’ The California and Texas school financing systems are similar in effee'

to the systems used in 49 of the 50 states. Hawaii is the only state without

0 9 6 8 }k °° ^lstnct contro* ° f education. Sec Hawaii Rev. Laws, §§296-2, 298^2

—3—

Amici are gravely concerned that the “ equal pro

tection standard of review as applied to state public

school financing systems by the court below in this

case, and by the California Supreme Court in Serrano

r. Priest, supra, if upheld by this Court, would place

a constitutional straitjacket upon local school boards,

state legislatures and Congress in their attempts to

solve and adjust the myriad o f problems involved in

the day-to-day and on-going operation o f this nation’s

public school systems.

Amici believe that one o f the* geniuses o f the public

school systems in America in general, and California

in particular, has been the incentives for and abilities

o f local school boards and state legislatures, democrat

ically elected, to experiment and innovate in finding

solutions to educational problems, many o f which are

o f purely local concern and others which are o f un

iversal application. The responsiveness o f the local

school district to the needs, desires and problems o f

the local populace would inevitably lie drasticallv im

paired by application o f the constitutional rule o f law

sought to be established by A ppellr--

STATEMENT

This case presents to this high Court fundamental

questions concerning the drastic restructuring o f a

state’s local governmental services, and the role to be

Flayed by the judicial branch o f government in doing

so. The impact o f the decision to be made in this case

4r

will be lelt not only by the thousands o f school dis

tricts in -19 of the 50 states, but by reason o f the logi

cal difficulties in distinguishing educational services

troni other important governmental services provided

by local units o f state government, the impact o f this

decision will surely be felt by almost all such local

governmental units with respect to their provision o f

important services in their respective communities.2

The strategies employed in this case were fully

mapped out in 1970 by Professor Coons and his asso- -

eiates in their book “ Private Wealth and Public E d

ucation.’ '3 This book was dedicated by its authors “ To

nine old friends o f the children,” and the validity o f

the arguments contained in their book are now pre

sented to this Court for determination.

Tt is this book that first presented the disarmingly

simple formulation o f a proposed new principle o f

“ equal protection” constitutional law. Coons’ “ sim ple”

formula is: “ The quality o f public education may not

be a function o f wealth other than the wealth o f the

state as a whole.” (Coons, et al., supra, Footnote 3,

Introduction, p. 2.)

It may be seen from the Order appealed from that

the District Court below fully embraced this formula.''

-A lawsuit challenging state and local legislation regulating the funding

of police and fire proteetion sen ices on the basis of the Serrano rule has

already been f. J in California. A "5>rr<itio” -type complaint, San Anselmo

Police Officers Association, et al. r. The City of San Anselmo, et al., 61302,

was filed on May 3. 1972, in the County of Marin.

3Coons, John P.. Chine III, Win. H., Sugarman, Stephen D., Private

Wealth and Public Education, the Belknap Press of Harvard University Press,

Cambridge, Mass. (1970).

•*337 F.Supp. 280, 285-286.

The California Supreme Court, the first to declare an

entire state's system o f financing its public schools to

he unconstitutional, likewise adopted Coons’ thesis."

The California Supreme Court emphasized in its

Modification o f Opinion that inasmuch as the ease in

volved an appeal from a judgment o f dismissal en

tered upon the sustaining o f general demurrer to the

Complaint, it was not a “ final judgment on the merits.”

The Supreme Court remanded the case to the trial

court with directions to overrule the demurrers and to

allow defendants a reasonable time to answer. The

Answer was filed on May 1, 1972, and the case is now

being prepared for trial.

As Coons points out, the system o f financing pul>-

Jic schools which is here under attack is one o f many

variations of the so-called “ foundation plan.” The con

ceptual basis for the “ foundation plan,” the purpose

o f which was to make adjustments in state contribu

tions to public school districts within the state to ac

count for district wealth variations, was originated by

George 1). Strayer and Robert M. Haig in 1923.® The

“ foundation plan” as utilized by most o f the state?

with numerous variations was developed by Paul R

r’Serrano v. Priest, 5 Cal.3d 584. 589, 187 P.2cl 1211, 96 Cal. Rptr. 601

“ Wc have determined that this funding scheme invidiou discriminate

against the poor because it makes the quality of a child’s education a functiot

of the wealth of his parents and neighbors.”

uStraycr, G. D. and Haig, R. M.. Financing of Education in the State c

New York (New York, 1923).

7Coons, supra, p. 63; Mort, P. R., Reusser, W . C. and Policy, J. \V

Public School Finance, 3d Ed. (New York, 1960).

—6—

will not undertake to describe the “ founda

tion p lan ’ * used in the State o f Texas, which is under

attack here, as tins will no doubt be fully described in

the briefs o f the parties to the suit. The California

Foundation Program is described by the California

Supreme Court in Serrano r. Priest, 5 Cal.3d 584 591

595. ’ 1 ’

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. 1 he District Court below erroneously held that

the complex system o f laws providing for the financing

o f the Texas public school system violates the ‘ ‘ equal

protection” clause o f (he Fourteenth Amendment to

the United States Constitution. The District Court

erroneously applied the onerous standard o f review

whereby the defendants were required to carry the

burden o f showing that its legislative classifications

were necessary to promote compelling state interests.

The first question to be resolved in this case is “ What

standaid ot review is to be applied in determining the

validity o f the complex public school financing law s?”

In uncritically relying upon Serrano v. Priest, 5 Cal.

3d 584, 487 P.2d 1241, 96 Cal.Rptr. 601, the District

Court failed to consider vital questions and factors.

The District Court should have carefully analyzed the

alleged suspect classification o f wealth and noted that

ihis classification involved wealth o f school districts

niul not wealth o f people. The District Court should

have noted that the alleged “ fundamental” interest

(quality o f education) allegedly affected by the alleged

— i

“ wealth ’ classification was not an interest o f people

in quality education but rather an interest in not beino-

unduly burdened in paying taxes. The court failed to

take into consideration, in determining its standard -of

review, numerous other factors, including the individu

al interests o f parents in directing the upbringing and

( diu ation o ( their children, vital societal or government-

al interests in permitting within reasonable limits local

community control in making decisions affecting the

schooling o f the children in the community and in al

locating local public funds in support thereof, the ne

cessity o f permitting the Legislature and Congress to

remain free o f a constitutional straitjacket with re

spect to their efforts to improve public education and

make innovations therein, and the ability o f the courts

to fashion and enforce fair and appropriate remedies

as compared with the ability o f the Legislature and

Congress to deal with the complex and rapidly changing

problems in public education. Applying all these con

siderations, the standard o f review to be applied to

this complex set o f school financing laws must lie less

onerous than the one applied by the District Court.

2. Under any standard o f review w h i c h might

fairly and reasonably be applied to the complex school

financing laws of Texas, the laws are valid under the

equal protection clause. The people o f Texas, including

the parents o f children attending public schools in that

state, have expressly attempted to preserve and pro

tect, through their financing system, their compelling

interest in assuring essential educational services for

—8—

aH C,n!(lrtm’ w1,1lc at the same time making appropriate

accommodations to the vital interest o f parents in local

communities in the course those educational services

take. The individual, societal and governmental inter

ests served by the Texas school financing laws are not

merely important, they are compelling. This is true

especially when it is considered that the school financ

ing laws are necessarily complex if they are to attempt

to make provision for the differing educational needs

o f students, and the inability o f plaintiffs to establish

feasible and better alternatives to meet those differing

educational needs while accommodating a reasonable

degree of local decision-making with respect to the ed

ucation o f the children. The classifications made in the

school financing laws o f Texas promote these compel

ling interests in such a way as to satisfy any realistic

standard o f judicial review.

3* Independent o f the foregoing, the monumental

nature o f the task o f more fairly allocating financial

resources o f the state among the school districts is one

which the courts are not equipped to tackle. This ne

cessarily complex, t i g h t l y interwoven and rapidly

changing set o f laws calculated to approach excellence

in the providing o f educational sen-ices to students

o f widely varying educational needs, is such that only

the Legislature, local school boards, and Congress are

equipped to handle. The resources available to them

far outstrip the resources available to the courts to

deal with these complexities. These problems are far

better tackled by experts working together t o w a r d

common goals than by courts relying upon the service

o f experts in adversary proceedings. W ere the court

to undertake the staggering- task ol closelv monitorinj

efforts o f the Legislature, school boards and Congres

with respect to their efforts to improve the qualitv o

public education, they would to that extent eneourag

those bodies to deem themselves absolved o f their re

sponsibilities, with the further adverse consequence o

subjecting the results o f such efforts as they migh

continue to make to extreme uncertainty, with result

ing,doubts as to the validity o f school district taxes ant

contractual commitments. The courts should accord

ingly exercise judicial restraint a n d evidence thei:

faith in tiie democratic, processes, the arena in whirl

solutions to these complex problems have historic-alb

and are now being hammered out.

-1. In any event, the judgment below should be re

versed because the order granting the injunction lack,

specificity and fails to describe in reasonable detai

vdiat the defendants must do in order to avoid tin

drastic contempt remedy available to enforce the order

The order, in enjoining the defendants from giving am

force or effect to the Texas seho, * ' emeing law s^ in

sofar as they discriminate against plaintiffs and other-

°n the basis o f wealth other than wealth o f the State