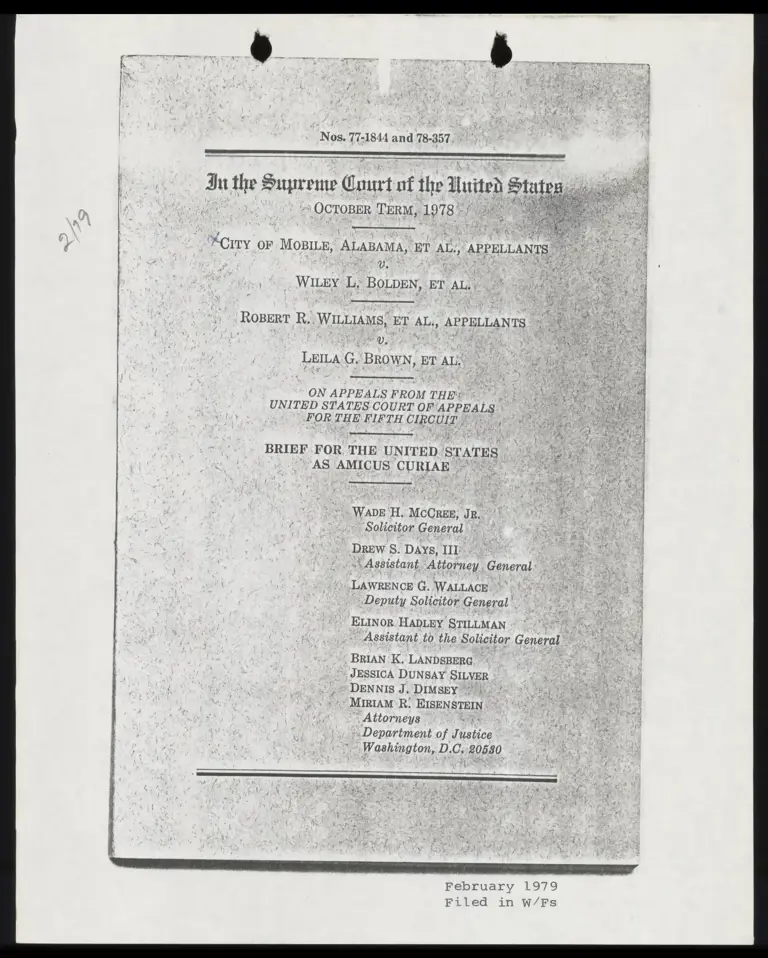

Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 17, 1979

115 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1979. 0c33aa7c-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/043099a0-e6ef-4d86-a4e3-047ce9d54695/brief-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

"Nos. 77-1844 and 78-357.

Ju the Supreme Gar of the tite States ie

+ OCTOBER TERM, 1078+

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, ET i APPELLANTS Tar

V.

WILEY Li. BOLDEN, ET ALLL

RoserT 2. WiLLiaws; ET AL, APPELLANTS

“0,

I GBR, ET ALL 5

ON APPEALS FROM THE": oe

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FILTH CIECUIT Frit

BRIEF FOR, THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE ~

+. WADE H. MCCREE, JR.

«+ Solicitor General

DREW S. DAYS, III

A Assistant, Attorney. General:

LAWRENCE G. WALLACE |

‘Deputy Solicitor General

"ELINOR HADLEY STILLMAN = RT

Assistant to the Solicitor General

BRIAN 'K. LANDSBERG

- JESSICA DUNSAY SILVER

DENNIS J, DIMSEY |

MIRIAM R. EISENSTEIN

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20580

February 1979

Filed in W/Fs

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1978

No. 77-1844

City or MoBILE, ALABAMA, et al.,

Appellants,

Vv.

WiLey L. Borpen, ef al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

J. U. BLACKSHER

LArRrYy MENEFEE

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

Epwarp STILL

Suite 400

Commerce Center

2027 First Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

JACK (REENBERG

Eric ScENAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Appellees

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Questions: PreSens od. cide icemistsiviohe sae sseleiviorsis » « +

Statement

XI.

111.

® 8 8 © 0 0 6 0 8 2 8 PG GO GGL 9 et SET SEN Oe ee es

© © 8 © 0 5 9 5 0 0 0s TT ESO EE" SES eT Oe es ee soe

Mobile's At-Large System of

Election Violates Section 2

of the 1965 Voting Rights

ACL rico ein ie vies a Ble tee naa ee

Mobile's At-Large System of

Election Is Maintained And

Operated For The Purpose of

Discriminating On The Basis

Of RACE. oho vite ilies cin lo isibisih «Join win nies oo »

The District Court Correctly

Applied The Principles of

White v. Regester and Whitcomb

VuilCNaVEs cv ve ons nmnssismomesnrns

A. ° The Legal Standard Established

By White and Whitcomb .......

B. The Irrelevance of Intent

Under White and Whitcomb ....

C. The Applicability of White

~ and Whitcomb to Municipal

Bloctions .....coepbsesisects

D. The Application of White

and Whitcomb to the Facts

Of This (Case .cuddfdeecce casa

PAGE

11

n

18

36

37

33

61

67

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(Cont 'd)

PAGE

IV. Mobile's At-Large Election

System Violates the

Fifteenth Amendment ......... Bs ai 82

V. The District Court Correctly

Formulated A Remedy For The

Prove Violation ses ines 92

CONC US TION ot et esi ee rst sss sn tenasnsnoeiss %

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Abate v. Mundt, 405°U.8. 182 (1971) ....... 56

Allen v. City of Mobile, 331 F.Supp.

1134 (8.0. Ala. 1671) .ccerecnnessanssse 83

Allen v. City of Mobile, '18 7.E.P.

Cases 207:(85.D."41a. 1978) ...c..n..... 7

Allen v. Board of Elections, 393 U.S.

RESELL SRE LL CRI Co She Eg 5, 14, 16,

47 , 48

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399

(1964) 5 il BR rd innsinss 50

Anderson v. Mobile City Commission,

Civil Action No. 7388-72-H

SD A a: 1973) i cera verre ersines 73

Arizona v. California, 2830.8.

423 (103) 2. lr. creer css rt nes &

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Cont'd)

PAGE

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp.,

429 U.8 268 £1977) ... i ii Jolie ve 6,24,32,33,

35

Avery v. Midland County, 390 U.S.

rll LS Se RT a PR 9, 63, 64

Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U.S. 219

EY Ye aie d ai din dis ia Pra fini 88

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S 130

(19768) tosis resssinisnns Pale dale 9, 47,48,

52,00,65,%

Blacks United for Lasting Leadership,

Inc. v. City of Shreveport,

571 F.24 248 (5th Cir,

C1078) serve tsansraiinsssnnnininia . 158

Bradas v. Rapides Parish Police

Jury, S08 F.2d 1109

(53th Civ. 1975) vi cvvcitncrrisnes 68

Breare v. Smith, 321 F.Supp. 1110

{S.D. Tex, 1971) (viv eicsnrvinnne 45

Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.B. 483 (1994) ..:iceisvevrnennsn 29, 63

Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73

(1968) 1uuurnrsnsnsnnrsesssiias sine 40,41,55, 58

Chavis v. Whitcomb, 305 F.Supp. 1364

(S:D..Ind. 1969) .ccsivccisivsvns 41

Chapman v. Meier, 421 U.S. 1 (1975) .. 57.58.93

~ iii ~

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Cont'd)

PAGE

City of Richmond v. United States,

422 1.8. 338 (1975) wil. lh hn 17,30,47,48

Clark v. Uebersee Finanz Korp.,

332 U.8. 450 XX) uv vd isis 14

Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407

C1977) coven Bmcianess airs a ilaliild 8, 60

Cooke v. City of Mobile, Civil

Action No. 2634-63

(8.0. Ala. 1983) cnverennnnrnninis 73

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S5. 1

(1958) i FARRAR JR a 63

David v. Garrison, 553 F.2d 923

(Sth Cir. 1977). hb vcerivmnin ini, 68

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F.Supp. 872

£S..D. Ala. 1949) ...c cer. chines 27,33

East Carroll Parish School Bd. v.

Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1978) ..... 31,359,460

Erlenbaugh v. United States, 409

U:8. 239. (1973) ..codiondh du da 13

Evans v. Mobile City Lines, Civil

Action No. 2193-63

(S.D.0A2. 61983) sven vine iii ia 73

Fortson v. Dorsey, 379 U.S. 433

C1965) uiiidtndivdddeisvisriva. ia 6,7,39,95,46,

5 5-57

Garza v. Smith, 320 F.Supp. 131

(WD. Tex. 1971) oie renecevicessns 45

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Cont'd)

Georgia v. United States, 411 U.S.

526 (1971) ... ci iment enh nam tnt

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S.

330 £1969)... icv ivaicir mins sitar

Graver Mfg. Co. v. Linde Co.,

336 U.8 271 LYO48) i cnesnrnvcsns

Graves v. Barnes, 343 F.Supp. 704 (W.D.

Tox, 1970) oes icacas vs camnine sven

Gray v. Sanders, 377 U.S. 3533 (1963)

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347

$1015) A. csr st rasta satire tn

Hadley v. Junior College District,

7 0.8: 50° (1970) cresnnrisn igs sns

Hendrix v. Joseph, 559 F.2d 1265

Bn Th EE Lb a pe en aI

Hendrix v. McKinney, F.Supp.

(M.D, Ala; 1978) . or ceveo-tivnnss

Holt Civic Club v. City of Tuscaloosa,

47 U.S LW. 4008 (1978) .cvvrsnnis

Bunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385

(1000) sat rrr tastes sravareimsssis

Jenkins v. City of Pensacola,

F.Supp. {N.D. Fla., Aug.

Ey 1078) fees ness arses sic nnsses

18, 28

18

41,43,45

60, 81

83, 84,85

64

68

31

TABIeE OF AUTHORITIES

(Cont'd)

Keyes v. School District No. 1,

413 4,5. "189 (1073) “ve is si urs

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors, 554

B.24 139 {Sth Civ. 1977)... recs.

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939)

Lane v. Wilson, 98 F.2d 980

CIO Cir 1938) |. coco ivr enna

Lucas v. Colorado General Assembly,

377 U.S. 713 (1984)... . os nisviers msgratis

Mayor v. Educational Equality League,

415 0.8. 6805 (1974) +n. esnie cremans

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184

L196) ccs ¢ rininuine sts ops sasunns + epi sar ats

Nevett v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209

{Oth Cir. 1078) oo ovvcoes issue

N.L.R.B. v. Drivers Local Union,

362 B.S. 279, 01980). ocr snes ccs cir ivin

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S.

112 (1970) .convrosmmopinms snnnps is

Paige v. Gray, 437 F.Supp. 151

(M.D, Miss, 1975) iu. unsicoine ash

Palmer v. Thompson, 403 U.S 217

30 a RL SE a

58

36

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Cont'd)

Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379

C1971) ccna u uriansnocsits

Pollack v. Williams,

322 U.8. & (1984) Javea

Reynolds v. Sims, 377

US. B33-C1964) 1.00, ois sions

Salyer Land Co. v. Tulare Water

District, 409 U.S. 719 (1973)

Sawyer v. City of Mobile, 208

F.Supp. 548 (S.D. Ala. 1963)

Sims v. Baggett, 247 F.Supp. 96

(MD, ALS Q9B3) vs cuir sniaien

Slaughter House Cases, 16 Wall. 36

(1873) eianensniampnolnelnns

Smith v. Allwright, 32) U.S.

649 (1944) Juce vc vee vernninnns

Smith v. Paris, 257 F.Supp. 901

(M.D. Ala. 1968) css. .encses

South Carolina v. Katzembach, 383

U.S. 30141968) 5veeeonneine

Spector Motor Freight Co. v.

McLaughlin, 323

U.S. 101 C1944) 00 Ja itd. 0s

e eo 0 a oo

ee 0 oo

® eo eo oo

PAGE

86

6, 8,37,38,

4+ 7-66

65, 66

73

27

32

86

X2

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Cont'd)

Stewart v. Waller, 404 F.Supp.

208 (X.D, Miss. 19753) ve. ivvvasis,

Swann v. Charlotte Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S.

bP C3071) re. cs eicsnosnsbnansnsen

Taylor iv. Georgia, 315 U.S. 251

CRO42) ooene ren sie tense snnnnsnsnns

C1953) ivi iets Sear a a

Thomasville Branch of the NAACP

v. Thomas County, 571 F.2d 257

{5th Cir. I078) |. ih nis iain

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey,

430°U.S. 144 (1965)... uss ny

United States v. Board of Commissioners

of Sheffield, 55 L.Ed.2d 148

(ISTRY it ies cn seat

United States v. Democratic

Executive Committee, 288

F.Supp. %3 (M.D. Ala. 1978) .....

United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S.

367 C1988) |... cetera

United States v. State of Alabama,

192 F.Supp. 677 {M.D.

Bla. 1961) ......ccvis iii verini

PAGE

31

31

88

46

68

8, 60

18.32,47,

63, 66

32

84

28

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Cont'd)

PAGE

United States v. State of Alabama,

252 F.Supp. 95 (M.D. Ala. 1966) ... 26

Washington v. Davis, 426

BeBe 229 (1976) wecoeicecosisnennens 8,10, 54,

57-61, 86

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124

LGTY) acne vns sisi senso 5 anes ns 2,36,37,40-

43,46 ,49-67,

81

White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755 01973) csi nites 2,6-10,18, 34-

37,43-67,75,

80-82

Williams v. Brown, No. 78=337.4c. wuss ne 76

Wise v. Lipscomb, 57 L.Ed.2d

GLY CYO78) cos cies vis on tiontiss as vio ome » 60,65, 92,93,

85

Wood v. Strickland, 420

U.S. 308 (1975) ... seinsicisie simaivrenis 12

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118

U.S. 356 CI898) ..... vse vivecs vn 62, 88

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d

1297 5th Cir. 1973) verses ceceeie 31

- 1x -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Cont'd)

PAGE

Constitutional Provisions

Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S.

Constitution we ieinmssseerssors sos 87

Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S.

CONSE ALUL ION s,s rsrsnssrossness 16.582,.23

Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S.

CONSEIERLION cose envrsveressnnssi . 2,10,82-0})

Statutes

28 0.8.0. (8134304) i... ..cincucnnncnans 16

Voting Rights Act of 1963, ¢

a 2,4,}¥1-17

Voting Rights Act of 1965, $4 ......... 15

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 35 ....s vee 4,12-16, 32

Ala. Code $31V=43-40 (1875) J. vecennne. | 19

Ala. Code 8311-44-11 019753) 45.) voces bus 20

Ala. Code App. §1247 (216a)

£1374. SUBD. Ya tore eis aces sioninels sis sas ens . 2}

Ala. Code App. $1603 (1966 Supp.) ..... 21

Ala. Acts, 1965 Reg. Sess., No. 823 ..,. 21,30

- Np w=

{

|

|

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Cont'd)

Ala. Acts, 1956 lst Extra. Sess.,

No. 82 .viivviviBecnsnisniene

Ala. Acts, 1956 2d Extra. Sess.,

Noo 18 uses cnndunitss uueidiuite

Ala. Acts, 1956 24 Extra. Sess.,

NO. 38. coiiouio vse itovnisiate s visio av

Ala. Acts, 1956 24 Extra. Sess...

NOG 8] nev nits iontsstasinetiv. sm

Ala, Acts, 1903 Reg. Sess., No. 47 ....

Other Authorities

Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 3d Sess.

Hearing Before the Subcommittee on

Constitutional Rights of the

Senate Judiciary Committee,

94th Cong., lst Sess. (1975)

Statistical Abstracts d972 ive eines

United States Census, City County

Data Book (1972). «+m sn suemmieies

1970 Census, Characteristics of

Population, iVeolivesosseeeses

United States Commission on

Civil Rights, With Liberty

and Justice for All (1939)...

- x1 -

PAGE

olein ed 30

corer 29

enobiiisin 29

27

we were 88-90

32

> etnies 64

cowie 30,76

cade 66

th end 28

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Cont 'd)

United States Commission on Civil

Rights, Voting 1951) .....0vivess

S. Lawson, Black Ballots: Voting

Rights in the South, 1944-1969

(1976) ® © ® © 0 0 00 0° 0 0 0° 0 0 0° 0 0 0 00 O° 00 0 © 0

Municipal Yearbook: 1978

L. Tribe, American Constitutional

1a £1878) Loerie ais nsa ann snnse

T.H. White, The Making of the

President 1960 (1981) .....ce000e.

Derfner, "Racial Discrimination and

the Right to Vote", 26

Vand. 1. Rev. 323 (1973) ..v0cevss

McLaurin, "Mobile Blacks and World War II:

The Development of Political

Consciousness," 4 Proceedings

of the Gulf Coast History and

Humanities Conf. 47 (1973) ........

Parker, "County Redistricting in

Mississippi: Case Studies in

Racial Gerrymanding"

4o'Mise 7h. J."391 (1973)... ner eve

Shofner, "Custom, Law, and History:

The Enduring Influence of Florida's

Black Code, The Florida Historical

Quarterly=277"CJan. 1977) ¢.. ve cc.

- Xi1 -

28

50

31

26

31

51

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1978

No. 77-1844

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al.,

Appellants,

Vv.

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States Court Of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

GF Should this Court overturn the con-

current findings of fact of the two courts below

that Mobile's at-large election system is main-

tained and operated for the purpose of discrimi-

nating against black voters?

2. Did the district court clearly err in

finding that the Mobile's at-large elections

"operate to minimize or cancel out the voting

strength” of blacks in violation of White v.

Regaster, 412 U.s. 755 (1973), and Whitcomb v.

Chavis, 403 U.8. 124 (1971)?

3. Does Mobile's at-large election system

violate the Fifteenth Amendment or section 2

of the 1965 Voting Rights Act?

4. Did the district court err in fashioning

a remedy for the proven violation?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Black citizens brought this class action to

challenge the at-large system for electing

Mobile's city commission. The complaint alleged

that the overall electoral structure was main-

tained to discriminate against blacks and that it

permitted a hostile white majority to bar blacks

from effective participation in the political

process. The district judge heard 37 witnesses

during a six day trial, received over 150 docu-

mentary exhibits (including computer analyses of

election returns), and personally toured the city

accompanied by the lawyers for all parties.

In October, 1976, he issued extensive findings of

fact and concluded that the at-large election

of Mobile's city commissioners unconstitutionally

diluted black voting strength, and was invidiously

discriminatory in purpose. J.S. 40b-42b.

Following the failure of a bill to reappor-

tion Mobile in the 1976 state legislature, and

in light of the imminence of city elections in

August 1977, the district court asked the parties

to propose remedial plans. The city defendants

opposed the election of a commission from single-

member districts, and expressed a preference for

a mayor-council form of government if single-

member districts were to be used. The defendants,

however, refused to propose any plan that did not

fully preserve at-large elections, although

agreeing to nominate two persons whom the court

appointed to a three-man advisory committee. The

advisory committee proposed a mayor-council plan

based largely on the mayor-council plan in opera-

tion in Montgomery, an Alabama city of comparable

size. After soliciting further comments from all

parties and from various other Mobile elected

officials, and after making certain modifications,

the district court adopted the committee's single-

member district plan and ordered that it be used

in the 1977 elections. At the same time, the court

offered to dissolve its injunction should the

legislature enact its own constitutional plan,

and it stayed the remedial elections pending

appeal. J.S8. 3d; A. 8.

The court of appeals affirmed the district

court's judgment and findings of fact. It

rejected the city's contention that an election

system may be maintained for a discriminatory

purpose so long as it was originally created for a

racially neutral reason. J.S. 13a-17a.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

i. Section 2 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act

prohibits the use of election practices which

"deny or abridge the vieght . . . to vote on

account of race or color." This should be con-

strued in pari materia with section 5 of that Act

which forbids certain jurisdictions to use new

election practices which will have the 'purpose

or . . . effect" of so denying or abridging

the right to vote. Both sections are concerned

with the same type of denial or abridgement;

section 5 merely establishes special procedures

for new practices in particular states and sub-

divisions.

The meaning of the Act as applied to dis-

tricting plans is well established. Blacks cannot

be subjected to a districting system which would

"nullify their ability to elect the candidate of

their choice." Allen v. Board of Elections,

393: 8.8. 344, .569 (196%)... The courts below

correctly found that Mobile's at-large election

system operated in just that manner.

II. The courts below found that Alabama

had rejected the use of single-member city council

districts in Mobile in order. to prevent the

election of black city officials. The evidence

before those courts included uncontradicted

testimony by members of the state legislature that

this .was the reason for maintaining at-large

elections, as well as a long history of inten-

tional discrimination by Alabama officials against

black voters. At-large plans adopted by the

legislature for electing the state House and

officials of other cities have been invalidated by

other court decisions as racially motivated. This

Court should not disturb the concurrent findings

of fact of the two courts below that the legisla-

ture was also acting from racial motives in

rejecting plans to permit Mobile to use single-

member districts.

The courts below correctly held that a

racially motivated decision to maintain a prac-

tice or procedure violates the Fourteenth Amend-

ment even if the practice or procedure was origin-

ally created for a racially neutral purpose. In

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Develop-

ment Corp., 429 U.S. 268 (1977), which establishes

the method of proving racial motivation, the

decision at issue was a refusal to alter a pre-

existing zoning classification.

IIT A. Reynolds v. Sims, 3770.8. 533 (1964),

prohibits the use of election systems which

systematically overweight the votes of one group

while underweighting the votes of another. In

Reynolds that unequal weighting was achieved by

placing voters in districts of unequal popula-

tion. Fortson v. Dorsey, 379. .U.8 433 (1963),

recognized that such unequal weighting could come

about in other ways including, under certain

circumstances, through the operation of an at-

large election system.

White v. Regzester, 412 U.S. 753.:(1973),

presented such circumstances. In that case whites

by voting as a bloc selected and controlled

|

|

\

all the legislators elected at-large from Dallas

and Bexar counties in Texas. The votes of

blacks and Mexican-Americans were thus systemati-

cally nullified. The system was the functional

equivalent of one in which all whites lived in a

district with an excess number of legislators,

while blacks and Mexican—-Americans lived in a

district with no representatives at all. As

a result of this system virtually no blacks or

Mexican-Americans were elected to the legislature,

and the white legislators were unresponsive if not

hostile to the interests of minority voters.

White was not based on the existence of racially

exclusive slating practices; there was no slating

in Bexar county, and the slating in Dallas county

was merely symptomatic of the underlying racial

and political realities.

B. White does not require a showing of

racial motivation in the creation or maintenance

of the at-large system. Fortson and its progeny

repeatedly stated that they applied to at-large

election systems which 'designedly or otherwise"

minimize the voting strength of a disfavored

group. 379 U.S at 433." White itself contained no

discussion of the purposes behind the Dallas and

Bexar county plans. - White, as Reynolds v. Sims,

derives from that branch of Equal Protection law

which prohibits interference with or impairment of

the franchise because it is "a fundamental right."

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S 229 (1976), on the

other hand, applies to the Equal Protection

prohibition against 'racial classifications", and

only as to that aspect of the Fourteenth Amendment

is proof of racial intent necessary.

This Court has subsequent to Washington v.

Davis repeatedly referred with approval to the

dilution rule of White. Connor v. Finch, 431

. U.S. 407, 422 (1977); United Jewish Organizations

y. Carey, 430 U.S 144, 165, 170, 179 €1977).

OC. The appellants never urged in the lower

courts that White was inapplicable to city elec-

tions, and have thus abandoned the issue. White

should be applied to the election of local govern-

ment officials. Reynolds v. Sims, from which

White stems, applies to such local elections.

Avery v. Midland County, 390 U.S 474 (1968).

Elections of local officials frequently have a far

greater impact on voters than the selection of

state legislators. This Court applied the White

standards to the election of city officials in

Beer v,. United States, 425 U.8.°130, 142 n. 14

(1976).

D. The courts below correctly found that

Mobile's at-large election system operates to

effectively disenfranchise black voters. The

evidence showed, and the district court found,

that whites vote as a bloc against black candi-

dates or white candidates who are supported

by black voters, that no black has ever won an

at-large election in Mobile, that no black candi-

date could do so under the present system, and

that under the all-white city commission Mobile

had engaged in a wide variety of practices dis-

criminating against its black residents. The

record in this case contains the same evidence

deemed sufficient to establish a constitutional

violation in White. The district court's finding

of such.a violation, resting -on: "a blend of

history and an intensely local appraisal of

the design and impact of the [Mobile] multi-member

- 10 -

district in the light of past and present reality,

political and otherwise,'" should be upheld. White

v. Regester, 412 U.S at 769.

IV. The Fifteenth Amendment prohibits the

use of election systems "which effectively handi-

cap exercise of the franchise by the colored race

although the abstract right to vote may remain

unrestricted as to race." Lane v. Wilson, 307

U.S. 268, 275 (1939). Lane does not require any

showing that such barriers were racially motivat-

ed. In view of the fact that the Fifteenth

Amendment singles out the franchise for special

protection, a broader standard is appropriate for

election laws burdening blacks than under the

general prohibition against racial classifications

contained in the Fourteenth Amendment. See

Washington v. Davis, supra.

vy. The district court did not err in

formulating the remedy in this case. Despite the

finding of a violation the defendants refused to

propose or enact a remedy. The defendants did

indicate, however, that if at-large elections were

- 1 =~

to be abolished, they opposed continuation of the

commission form of government and preferred a

mayor-council plan. The district judge therefore

ordered into effect a mayor-council plan based

largely on the mayor-council plan in operation in

Montgomery, Alabama. The court further provided

that its plan could at any time be superseded by

any other constitutional plan authorized by the

legislature. Thus Alabama is free to use a

commission form of government with commissioners

elected from single-member districts, a system

actually utilized in several other states.

ARGUMENT

i MOBILE'S AT-LARGE SYSTEM OF ELECTION

VIOLATES SECTION 2 OF THE 1965 VOTING

RIGHTS ACT

The complaint in this action alleges that

Mobile's at-large election system violates section

2 of the ‘1965. Voting Rights Act. A. 18. "That

provision, codified in 42 U.S.C. §1973, provides:

No voting qualification or prerequisite

to voting, or standard, practice or procedure

shall be imposed or applied by any State or

political subdivision to deny or abridge the

right of any citizen of the United States to

vote on account of race or color.

-12 -

Both courts below noted the existence of this

statutory claim, but neither decided it. J.3,

da=da n. 3; cA, 27. The practice of this Court,

however, 1s to avoid the decision of constitu-

tional issues if it is possible to resolve a

case on Hondonstivus Loasy grounds. Wood v.

Strickland, 420 U.S. 308,:314:(1975); Spector

Motor Co. vi Mclaughlin, 323°-0.5,° 101,% 105

(1944).

Section 2 does not on its face require that a

forbidden practice involve a purpose of denying or

abridging the right to vote. The phrase "on

account of" appears to contemplate some causal

relation between abridgement and the race of the

victim, but does not suggest that that connection

must be a motive to discriminate in the mind of a

legislator. The legislative history of section 2

throws no direct light on the meaning of that

provision.

Elsewhere in the Voting Rights Act, however,

Congress provided a more complete definition of

the types of election practices it sought to

prohibit. Section 5 of the Act, :42 U.S.C.

§1973c, establishes special procedures for review-

ing new election laws and procedures in certain

- 13 -

jurisdictions, providing that such a law and

procedure may not be enforced unless the jurisdic-

tion involved can establish that it "does not have

the purpose and will not have the effect of

denying or abridging the right to vote on account

of. race or color." As used in section. .3.the

phrase '"on account of" cannot refer to legislative

motivation, or section 5 would turn on the pres-

ence of a "purpose or effect of purposefully

denying or abridging the right to vote."

It is unlikely that Congress used the words

Mon account of" in section .2 .in.a.different

sense than they were used in section 5. On the

contrary, section 2 should be construed in pari

materia with section 5. See Erlenbaugh v. United

States, 409.0.8 -239, 243-44 .(1973)..- This Court

has consistently taken account of a later statute

"when asked to extend the reach of [an] earlier

Act's vague language to the limits which, read

literally, the words might permit.” . N.L.R.B, wv.

Drivers Local Union, 362 U.S. 279, 291-92 (1960).

"[I]f it can be gathered from a subsequent statute

in pari materia what meaning the Legislature

attached to the words of a former statute, they

will amount to a legislative declaration of

- iu ~

its meaning. . . ." United States v. Freeman, 3

How. (44 U.S.) 556, 564-63 (1845). These con-

siderations apply with particular force when

construing related portions of a single statute.

In this case section 5 of the Voting Rights Act

should be regarded as identifying with greater

specificity the types of prohibited practices

alluded to more vaguely in section 2.

This construction serves to give to the

Voting Rights Act "the most harmonious, comprehen-

sive meaning possible." Clark v. Uebersee Finanz-

Korp, 332 U.S. 480, 488 (1947). Section 5 is "an

unusual, and in some respects a severe, procedure

for insuring that states would not discriminate on

the basis of race in the enforcement of their

voting laws." - Allen v. Board of Elections, 393

U.S. 544, 558 (1969) (emphasis added). With

regard to new election practices in covered

jurisdictions, section 5 requires approval prior

to implementation, limits approval proceedings to

submissions to the Attorney General or an action

before a three-judge federal court in the District

of Columbia, and places the burden of proof as to

factual issues on the proponents of the proposed

practice. These procedures were fashioned to

- 15 -

shift the advantages of time and inertia from the

perpetrators of the evil to its victims." United

States v. Board of Commissioners of Sheffield, 55

1L..24.24 148, 160 (1978). There is, however, no

reason to believe that Congress also intended to

set a different substantive standard under section

5 than the standard established by section 2 for

old laws in the covered jurisdictions and for new

and old laws in the rest of the country.

If sections 2 and 5 contained different

substantive standards a number of anomalies would

result. Within a state covered by section 5 a

single election law could be valid in ome city and

invalid in another based solely on the date on

which each city put the law into operation. See

Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379, 394-95 (1971).

Practices forbidden in section 5 jurisdictions

would be permissible in the other states, even

though the practices had the same purpose and

effect in both instances. Section 4 of the Voting

Rights Act did establish temporarily a narrowly

focused different substantive standard for covered

jurisdictions, prohibiting there the use of

certain specified "tests or devices"; but Congress

in that instance was well aware it was establish-

- 16 =

ing different election rules than existed outside

the South, and it acted to abolish that distinc-

tion five years later by making that ban nation-

wide. Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S 112, 133-34

(1970). This Court should not in the absence of

clear congressional intent read back into the Act

different substantive standards falling along

regional lines.

Once it 1s recognized that the standard for

judging election practices 1s the same under

section 2 as under section 5, the application of

section 2 to. this case is not difficult. Juris-

diction over section 2Z actions is conferred on the

federal courts by 28 U.S.C. §1343(4). Allen v.

Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 554-57 (1969),

holds that section 5 can be enforced by private

actions ; the reasoning of Allen applies a fortiori

to section 2, since the Attorney General is not

expressly authorized to enforce that section,

and absent private enforcement the guarantees of

section 2 might well "prove an empty promise."

393 0.5. at B7.

That the use of at-large elections may have

the effect of denying or abridging the right to

vote under section 5 has been repeatedly recog-

»:l7 -

nized by this Court. City of Richmond v. United

States, 422 U.8.-:358,.-:371. (1975); Ceoxgia v:

United States, 411 :U.S. 526, 332-35 .(1973);

Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S 379, 388-91 (1971).

City of Richmond noted that such at-large elec-

tions may do so by '"creat[ing] or enchanc[ing]

the power of the white majority to exclude Negroes

totally from participation in the governing

of the city through membership on the city coun-

cil. 2422 U.S. at- 371. The record;and findings

in this case, which we set out in, detail infra at

pp. 67-82, demonstrate that Mobile's at-large

election system had just such an impact. That

system placed 67, 000 blacks ina district with

122,000 whites, enabling the whites by bloc

voting to consistently exclude from the city

commission not only blacks but even whites who

had revealed an interest in serving the needs of

the black community. The system predictably

resulted in a city government which discriminated

in virtually every phase of its activities

against black residents of the city. This evi-

dence was sufficient to meet plaintiffs’ burden

of establishing a violation of section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act.

- 18 -

Ii. MOBILE'S AT-LARGE SYSTEM OF ELECTION IS

MAINTAINED AND OPERATED FOR THE PURPOSE

OF DISCRIMINATING ON THE BASIS OF RACE

Although the Questions Presented described in

the Jurisdictional Statement and Brief for

Appellants deal primarily with the application of

the dilution rule of White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755 (1973), the decisions below invalidated

Mobile's at-large method of election based on a

finding of discriminatory intent. J.S. l2a~15a,

30b. The constitutional prohibition against such

racially motivated election schemes is well

established. Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S.

339 (1960). Accordingly the first constitutional

issue presented by this appeal is the correctness

of the factual findings of discriminatory intent

made by the lower courts. This Court does not

ordinarily "undertake to review concurrent find-

ings of fact by two courts below in the absence of

a very obvious and exceptional showing of error."

Gravey Mfg, Co, v, Linde Co., 336 U.S. 271, 275

(1949). Appellees maintain that no such unusual

circumstances are present here.

-19- =

An assessment of the factual findings of the

courts below must begin with an understanding of

the history and details of Alabama statutes

regarding the structure of municipal government.

City and town governments fall into three cate-

gories. First, the structure that prevailed

throughout the nineteenth century, and which

continues today, is a mayor-alderman government ;

under this plan the method of electing aldermen

depends on the size of the city and number of

Y/

wards, within it.="A city the size of Mobile

would ordinarily elect most if not all of its

aldermen from single-member districts.2! Second’

since Bll Alabama municipalities have also been

authorized to use the commission form of govern-

ment, under which three commissioners are elected

at large and perform both legislative and ad-

1/ Ala. Code §11-43-40 (1975).

2/ Mobile presently has 31 wards. If it adopted

the mayor-alderman system Mobile would be required

by section 11-43-40 to reduce the number of wards

to no more than 2; the city council would consist

of one member from each of these districts plus a

council president elected at-large.

- 20 -

ministrative functions. 2) alabana general law

permits cities to adopt either the mayor-alderman

or commission form of government by referendum.

Of 420 Alabama cities only 14 presently use the

4/

commission system.— In recent years, however,

the mayor—alderman plan has proved unsatisfactory,

particularly for the larger cities, because the

mayor's powers are too ree ol Accordinaly,

authorization has been sought from the legislature

for a third form of government, a mayor-council

plan with a strong mayor. Instead of adopting

general legislation permitting all municipalities

to choose this plan, however, the legislature has

authorized it only on a case-by-case basis for

particular cities. A mayor-council plan was

3/1 Ala. Code $1l-44-1, et seq. (1975).

4/ The Alabama cities governed by commissions

are Arab, Bessemer, Brundidge, Cherokee, Florence,

Gadsden, Jasper, Madison, Mobile, Muscle Shoals,

Opelika, Troy, Tuscaloosa and Tuscumbia.

The use of the commission form of government

nationally is similarly uncommon. As of 1978 only

114 of 2477 cities over 10,000 used such commis-

sions, less than 57. Municipal Yearbook: 1978,

Table 3.

3/ The most serious problem is that the council

of aldermen can interfere with routine executive

functions. Tr. 349, 1152.

- 21 -

6/

authorized for Birmingham in 1953— and for Mont-

gomery in 1873: ta both cases the city voters

chose in a subsequent referendum to adopt such a

plan in place of the commission form of govern-

ment.

The actions with which the courts below were

primarily concerned were refusals by the legisla-

ture in 1965 and 1976 to permit the people

of Mobile to adopt a mayor-council plan under

which the city council could be elected from

single-member districts. In 1965 the legislature

authorized Mobile to adopt a mayor-council plan,

but expressly considered and refused to allow

Mobilians to opt for single-member distetets.

In 1976 the legislature considered and rejected a

proposal, known as the "Roberts piv, Veo

authorize Mobile to choose a mayor-council plan

with seven single-member districts and two at-

6/ Ala. Code App. §1603 et seq. (1966 Supp.).

1 Ala. Code App. §1247 (216a) et seq. (1974

Supp.) .

8/... Ala. Acts. Beg. Sess. 1965, No..823: sees also

P. Ex. 9%, pp. 40-41.

9/ A. 9, 250, 256,

- 22 -

large council members. In each case, we maintain,

and the courts below found, that the refusal to

allow Mobile to adopt single-member districts was

caused by fear that such districts would permit

the election of black candidates.

In Alabama proposals affecting only one city

are not as a practical matter considered by the

whole legislature. The actual functioning of the

legislature was described in detail by the dis-

trict court:

The state legislature observes a courtesy

rule, that is, if the county delegation

unanimously endorses local legislation

the legislature perfunctorily approves

all local county legislation. The Mobile

County Senate delegation of three members

operates under a courtesy rule that any one

member can veto any local legislation. If

the Senate delegation unanimously approves

the legislation, it will be perfunctorily

passed in the State Senate. The county

House delegation does not operate on a

unanimous rule as in the Senate, but on a

majority vote principle, that is, if the

majority of the House delegation favors local

legislation, it will be placed on the House

calendar but will be subject to debate.

However, the proposed county legislation will

be perfunctorily approved if the Mobile

County House delegation unanimously approves

it. J.S. 29b~30b.

- 23 -

Thus the decisions to forbid Mobile voters to

choose a plan with city councilmen elected

from single-member districts were made by the

Mobile legislative delegation.

The evidence before the district court

included direct testimony by members of the

Mobile legislative delegation who were in office

when single-member council districts were rejected

in 1965 and 1976. Robert S. Edington, who served

in the Alabama legislature from 1962 to 1974,

testified candidly about the reason for rejecting

such districts in 1965:

Q. Why was the opposition to single member

districts so strong?

A. At that time, the reason argued in the

legislative delegation, very simply was this,

that if you do that, then the public is going

to come out and say that the Mobile legisla-

tive delegation has just passed a bill that

would put blacks in city office. Which it

would have done had the city voters adopted

the Mayor Council form of government. P.

Ex. 98, p. 43.

Senator Roberts testified that in 1976, even

though the Mobile delegation was well aware that

blacks could not be elected or 'be able to elect

candidates of their choice" if only multi-member

- 24 r=

districts were used, a white State Senator from

Mobile had vetoed the Roberts proposal to

create some single-member districts. A. 255-58.

Representative Gary Cooper was ''relatively cer-

tain" the Roberts Bill had been opposed in the

legislature because "it would allow the possi-

bility for blacks to hold public office in the

City government". P. Ex. 99, p. 20. Represen-

tative Cain J. Kennedy explained that the prospect

of blacks winning public office was the primary

area of legislative concern regarding 1975 pro-

posals for single-member district elections for

the school board and county commission. P. Ex,

100, pp. 29-30. Such direct testimony about the

statements and motives of the legislators who made

the actual decisions in 1965 and 1976 was "highly

relevant." Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 268

£1977).

The direct evidence was supported by the

evidence and the district court's conclusions that

[4

the impact of the decision to reject single-

member districts bore ''more heavily on one race

than another." Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. at 266. No

i

- 25 -

black has ever been elected to the at-large

commission, and no black has ever won any at-large

election in Mobile City or County. Numerous

witnesses familiar with the local political and

racial situation in Mobile testified that no

black could win such an at-large election iV rue

district court concluded:

Black candidates at this time can

only have a reasonable chance of being

elected where they have a majority or a near

majority. There is no reasonable expectation

that a black candidate could be elected in a

city-wide election because of race polariza-

tion... J.S. 10b.

Thus the effect of barring the adoption of single-

member council seats, an effect of which the

legislators were well aware, was to prohibit the

election of blacks to city office in Mobile.

That that prohibition was the purpose, and

not merely the effect, of the legislative deci-

sions of 1965 and 1976 is also confirmed by the

long and deplorable history of discrimination in

voting by Alabama officials. The Alabama Con-

10/ See n. 41, infra.

- 26 -

stitutional Convention of 1901 enacted a number of

measures intended to disenfranchise blacks,

including a poll tax, a literacy test, “and

education, employment and property qualifica-

tions. Those requirements were so effective that

by the end of World War II only 275 blacks were

registered in Mobile County, compared to 19,000

Whites. sil tateed States v. State of Alabama, 252

F.Supp. 95 (M.D. Ala. 1966), held that the purpose

of these measures was to subvert the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments, and declared the poll

tax invalid because of the discriminatory intent

behind 30. 220, 1903 the legislature authorized

11/ P. Ex. 2, Mclaurin, "Mobile Blacks and World

War II: The Development of a Political Conscious-

ness," 4 Proceedings of the Gulf Coast History and

Humanities Conf. 47, 50 (1973).

12/ One convention delegate explained:

"* * * We want the white man who once voted

in the state and controlled it to vote again. We

want to see that old condition restored. Upon

that theory we took the stump in Alabama having

pledged ourselves to the white people upon the

platform that we would not disfranchise a single

white man if you trust us to frame an organic law

for Alabama, but it is our purpose, it .is our

intention, and here 1s our registered vow to

disfranchise every Negro in the state and not a

single white man." 252 F.Supp. at 98.

-27 -

political parties to exclude voters from primary

elections on the basis of race 23 the state

Democratic Party adopted an all-white primary

which remained in effect until well after Smith v.

Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944). In W946 the state

adopted a measure requiring voters to interpret

any provision of the Constitution; three years

later it too was struck down as an unconstitu-

tionally motivated "contrivance by the State

to thwart equality in the enjoyment of the right

to vote by citizens of the United States on

account of race or color". Davis v. Schnell, 8

F.Supp. $72,879 (8.D. Ala. 1949), aff'd 336 U.S.

933 (1949). Discriminatory application of regis-

tration requirements continued as a brutally

effective method of excluding blacks until adop-

13/ = Ala. Acts, 1903 Reg. Sess., No. 47, § 10.

- 28 =

tion of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.34 men

increased black registration appeared inevitable,

Alabama officials resorted to more sophisticated

measures to effectively disenfranschise blacks.

In 1957 the legislature gerrymandered virtually

all blacks out of the city of Tuskegee; this Court

held that such a clear "impairment of voting

rights" could not be accomplished by cloaking it

"in the garb of the realignment of political

subdivisions." Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S.

339, 345 (1960).

Mobile itself was the subject of special

legislative attention. By 1956, despite the

variety of discriminatory measures then in force,

14/ See, e.g., United States Commission on

Civil Rights, With Liberty and Justice for All,

pp. 59-75 (1959); United States Commission on

Civil Rights, Voting, pp. 23-28 (1961). A list of

injunctions in force against Alabama officials is

set out in Sims v. Baggett, 247 F.Supp. 96, 108,

n.24 (M.D. Ala. 1965). See also State of Alabama

Vv. United States, 192 F.Supp. 677 (M.D. "Ala.

1961), aff'd 304 F.2d 583 (5th''Cir.), aff'd

371 U.S. 37 C1962).

- 29 -

14% of Mobile's voting age black population was

registered. A. 574. With fear of desegregation

a burning political issue in the wake of Brown v.

Board of Education, 37 U.S 483 (1954), and with

the Eisenhower Administration pressing for enact-

ment of what was to become the Civil Rights Act of

B57, special sessions of the Alabama legislature

sought to preserve the state's segregationist

policies. The legislature enacted proposed con-

stitutional amendments to authorize legislation

establishing private, racially segregated schools’

and transferring public recreational facilities to

6/ : 1 :

private control— Resolutions were adopted

denouncing Brown itself and proclaiming Alabama's

"deep determination' to preserve its long estab-

7/

lished discriminatory policies ib Along with

15/ Ala. Acts. 1956 1st Extra. -Sess., Ro.” 82.

16/: Ala. ‘Acts. 19536 2d Extra. Sess. ; No." 67,

17/- Ala. Acts. 1956 28 Extra. Sess., No. -38.

- 30 -

this avowedly racist program, the legislature

adopted a statute annexing to Mobile several

substantial white suburbs, thus tripling its total

area, but carefully excluding two nearby black

8/

aeighborhoods 23 But for this annexation the

1970 population of Mobile would have been 547%

black, compared to the 35% minority within the

19/ Cf. City of

Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358 (1975).

In .1965 the legislature adopted a local

present enlarged boundaries.

tae mandating the allocation of specific

executive functions to each of the Mobile commis-

sioners; the Attorney General, acting under

section 5 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, inter-

posed an objection to this statute on the ground

18/. Ala. Acts, 1956 24. Extra. Sess., No. 18,

These neighborhoods had originally been included

in the bill when, as required by state law, its

contents were advertised in the local papers.

Mobile Register, March 2, 1956, p. lA.

19/ The annexed area is the southwest section

of the city boardered by Interstate 10 on the

north and Interstate 65 on the east. The 26

census tracts in this area have a population

of 70,689, of whom 67,414 are white. The total

population of the city is 189,986, of whom

122,100 are white. United States Census, City

County Data Book, p. 630 (1972).

20/ Ala. Acts, 1965 Reg. Sess., No. 823.

- 31 -

that it would as a practical matter preclude the

election of commissioners from single-member

districts. J.8. 3a, n.2

In recent years the principal device used to

disenfranchise Alabama blacks has been the crea-

tion or maintenance of multi-member districts

which submerge large concentrations of black

voters .2/ Perkins Vv. Matthews, 400 1D.S. 379, 23839

(1971). In 1965 the legislature created a number

of multi-county multi-member districts for elect-

ing the state House; they were struck down as

racially motivated in Sims v. Baggett, 247 F.Supp.

96 (M.D. Ala. 1965). Hendrix v. McKinney,

21/ The shift to at-large election schemes as a

fallback against the growing numbers of newly

enfranchised blacks 1s characteristic of other

Southern states as well. See Zimmer v. McKeithen

485 F.2d 1297, 1304. (5th. Cir. 1973)(en banc),

aff'd sub nom., East Carroll Parish School

Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976); Jenkins v.

City of Pensacola, F.Supp. {N.D. Fla.,

Aug, 11, 1978); Paige v. Cray, 437 F.Supp. 151

(M.D. Ga. 1977); Stewart v. Waller, 404 F.Supp.

206 (N.D. Miss. 1975); Derfner, "Racial Discrimi-

nation and the Right to Vote," 26 Vand. L. Rev.

523, 552-53 (1973); Parker , "County Redistricting

in Mississippi: Case Studies in Racial Gerry-

mandering,” 44 Miss... L. J. 391 (1973).

- 32 -

F.Supp.” = UAM.D. Ala. 197%), held that the

at-large plan for electing the Montgomery County

Commission was adopted by the legislature in 1957

“to dilute black voting strength”. F.Supp. at

Proposals to elect Democratic party offi-

cials at-large were found to have a discriminatory

purpose in United States v. Democratic Executive

Committee, 288 F.Supp. %3 (M.D. Ala. 1968), and

Smith v, Paris, 257 F.Supp. 901 (M.D. Ala. 1966),

aff'd, 326 F.24 979 (5th Cir. 1967). Acting under

section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, the Department

of Justice has disapproved a series of Alabama

statutes to create new at-large districts on the

ground that they had the purpose or would have the

effect of discriminating on the basis of vies 22)

The historical background of the 1965 and

1976 decisions thus reveals "a series of official

actions taken for invidious purposes’. Arlington

Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development

Corp., 429 U.8 at 267. Indeed, that history

includes one of the same official actions which

22/ Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Constitu -

tional Rights of the Senate Judiciary Committee,

9th Cong., "lst Sess., p. 398 (1975); see also

United States v. Board of Commissioners of Shef-

field, 55 L.Ed.24 148 (1978),

- 33 -

Arlington Heights cited as an example of such a

history of discrimination, 429 U.S. at 267, citing

Davis v. Schnell, and involves the same discrimi-

natory device at issue in this case.

In light of this evidence the courts below

properly concluded that the decisions of 1965 and

1976 were racially motivated. The district court

held:

The evidence is clear that whenever a redis-

tricting bill of any type is proposed

by a county delegation member, a major

concern has centered around how many,

if any, blacks would be elected. These

factors prevented any effective redistricting

which would result in any benefit to black

voters passing until the State was redis-

tricted by a federal court order. JS.

30b.

The Fifth Circuit noted the existence of "direct

evidence of the intent behind the maintenance of

the at-large plan". J.8. l4a. lt concluded that

“the district court's findings are not clearly

erroneous", J.S. 12a, and that they support its

conclusion that "invidious discriminatory purpose

was a motivating factor" in the maintenance of

- 34 ~-

Mobile's at-large election scheme. J.S. 154. 23/

The court of appeals properly held that a law

which is maintained for a discriminatory purpose

is unconstitutional regardless of the motive

which led to its original enactment. J.S. l13a-

l4a. Arlington Heights itself recognized that a

racially motivated decision to maintain the zoning

classification of a particular lot would violate

the Fourteenth Amendment regardless of the origin

of that .classification. 429 U.S. ar 257-58,

268-71 n.17. 1In this case we have, not unex-

plained and perhaps unconsidered legislative

23/ In a companion case, Nevett v. Sides, the

court of appeals noted that much of the evidence

which would support a finding of dilution under

White v, Regester, :412 U.S. 755 (1973), would

also be evidence of a discriminatory purpose in

establishing or maintaining the at-large system.

5721 F.24 209, 222-25 {5th Cir. 1978)... Nevett

suggested that "under proper circumstances’

evidence sufficient to establish dilution might

also be sufficient to establish a prima facie case

of intentional discrimination. 571 F.2d at 223.

What those circumstances might be was not decided

by the court of appeals. Neither is that issue

presented by the instant case, since, as the Fifth

Circuit noted, J.S. 14a, the record in this

case contains an array of other types of evi-

dence, both direct and circumstantial, of dis-

criminatory intent.

- 35 -

inaction, but two affirmative and express legisla-

tive decisions. The first is the adoption of a

statute in 1965 from which the possibility of

single-member districts was intentionally excluded.

The second is the de facto veto by a single state

senator of a single-member council plan. So long

as the motivation involved is impermissible,

no ground exists for distinguishing these legis-

lative actions from others to which the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments apply.

This case well illustrates the widsom of the

two court rule. The evidence in the record would

be sufficient to require a finding of discrimina-

tory motive even 1f this Court undertook to

reconsider that issue de novo. But the decisions

of the courts below, especially that of the

district court, involve more than the review of a

cold record. In conducting the ''sensitive in-

quiry" contemplated by Arlington Heights, the

district judge was able to bring to bear an

understanding of local political, legislative and

racial realities born of years of legal, judicial

and practical experience in the state. He was

able to assess the demeanor of the witnesses who

testified with direct personal knowledge of the

- 36

motives of the legislature. Both courts below

were able to weigh the evidence with a sensitivity

to the continuing problems in states with long

histories of de jure segregation. No judge

lightly undertakes to enter a finding of inten-

tional discrimination; the decision in a case such

as this 1s invariably tempered by a desire not to

impugn the motives of local public officials.

When a district judge 1s compelled to conclude

that those officials have acted from racial

malice, and does so on a record as substantial

as that in the instant case, that conclusion is

entitled to the "great weight . . . accorded

findings of fact made by district courts in cases

turning on peculiarly local conditions and circum-

stances.” Mayor v. Educational Equality League,

415 U.S..603,. 621 .n.20.01974).

II. THE DISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY APPLIED

THE PRINCIPLES OF WHITE v. REGESTER

AND WHITCOMB v. CHAVIS

In affirming the district court finding of

unconstitutionality the court of appeals relied on

the district court finding of purposeful discrimi-

- 37 =

nation. J.S., 12a~15,, The district court had

also found that Mobile's at-large plan impermis-

sibly diluted the votes of black residents in

violation of White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755

(1973), and Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124

(1971). J.8. -22b, 33b~34b. The court of appesls

upheld those findings of fact as well, agreeing

that they "amply support the inference that

Mobile's at-large system wunconstitutionally

depreciates the value of the black vote." J.S.

12a. The court of appeals, however, thought that

a violation of White required a finding of dis-

criminatory purpose. J.S. 2a. Appellees maintain

that White prohibits at-large plans that have such

effects regardless of the motivation behind them;

accordingly we urge that these findings afford an

alternative ground for affirmance.

A. The Legal Standard Established By

White and Whitcomb

The dilution standard applied in White and

Whitcomb derives from the one-person, one-vote

rule of Reynolds v. Siws, 377 U.S. 533 (1964),

n Reynolds proceeded from the principle that "any

alleged infringement of the right of citizens to

- 38

vote must be carefully and meticulously scrutin-

ized" because "the right to exercise the franchise

in a free and unimpaired manner is preservative of

other basic civil and polizical rights.” ..377

U.S. at $1. In Reynolds, also an Alabama case,

there were no formal or party barriers to voting.

But this Court held:

There is more to the right to vote than

the right to mark a piece of paper and drop.

it in a box or the right to pull a lever in a

voting booth. The right to vote includes the

right to have the ballot counted.... It also

includes the right to have the vote counted

at full value without dilution or .4dis~

count. ... That federally protected right

suffers substantial dilution ... [where a]

favored group [h]as full voting strength

[and] the groups not in favor have their

votes discounted. 377 U.S. “at” 35 n.19.

Nothing on the face of the districting plan in

Reynolds demonstrated such unequal weighting of

votes, but evidence regarding the population of

the state senate districts proved that such

inequalities existed. 377 U.S. zt. 58-370.

Only six months after Reynolds this Court

recognized that population differences were not

the only way in which a facially neutral district-

- 39 -

ing plan might undervalue the votes of some and

overvalue the votes of others. Fortson v. Dorsey,

379 U.S. 433 (1965), held that the use of multi-

member districts was not unconstitutional per se

merely because at-large voting "could, as a matter

of mathematics, result in the nullification of the

unanimous choice of the voters" of an area large

enough to constitute a single-member district.

379 U.S. at 433. Bur, PFortson warned:

It might well be that, designedly or other-

wise, a multi-member constituency apportion-

ment scheme, under the circumstances of a

particular case, would operate to mini-

mize or cancel out the voting strength

of racial or political elements of the

voting population. When this is demonstrated

it will be time enough to consider whether

the system still passes constitutional

muster. 379 U.S. at 439.

In such a case a 60% majority, if it voted as a

bloc, could control the selection of 100% of the

at-large officials; the votes of the majority

would carry full weight, while the votes of the

minority would have no value whatever. It would

be the functional equivalent of a scheme in which

the 60% majority resides in a district with

more representatives than were warranted by the

EY om

population of the district, while the 40% minority

lived in a district with no representatives at

all.

The next year Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S.

73 (1966), held that a scheme which in fact "would

operate to minimize or cancel out the voting

strength of racial or political elements of the

voting population'" would "constitute an invidious

discrimination,” 384 U.S. at 88, but concluded

that the multi-member plan in that particular case

had not been shown to have such an "invidious

result." 384 U.S. at 88-89. Burns noted that

there was no evidence in the record in that case

that the disputed plan, under the local conditions

there involved, would "by encouraging bloc voting

diminish the opportunity of a minority ... to

win seats.” 384 U.S. at 88 n.l4.

The first detailed consideration of the

dilution standard came in Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403

U.S. 124 (1971), where the Court rejected a claim

that a multi-member plan for electing state

legislators in Marion County, Indiana, would

operate to minimize the voting strength of black

voters. The Court held that the requisite mini-

mizing effect had not been proven. Whitcomb

“4 -

emphasized that, as in Burns, black candidates

had not lost because of bloc voting against

blacks, but because of ordinary partisan voting.

403 U.S. at 134 n.}l;, Blacks had been regularly

nominated by both the Democratic and tje Republi-

can parties, and had lost, when they did, only

when their entire party slate went down to defeat.

403 U.S. at 150 n.30, 152-53.2% hus direct

evidence demonstrated that minority voters had not

been disenfranchised by majority bloc voting

against minority candidates.

Whitcomb noted that this direct evidence was

confirmed by other evidence regarding the politi-

24/ It appeared that in 99% of all elections

since 1920 no candidate had lost when the rest of

his or her party's slate prevailed. Chavis v.

Whitcomb, 305 F.Supp. 1364, 1385 (S.D. Ind. 1969).

The importance of partisan rather than racial

considerations is underlined not only by the fact

that blacks often won in the majority-white

multi-member districts, but also by the fact that

black voters voted against even black Republican

candidates. Graves v. Barnes, 343 F.Supp. 704,

727 nn. 13 (3.D. Tex. 1970).

fi) -

cal and racial realities in Marion county. First,

minority candidates were not totally excluded from

the legislature or kept at nominal levels;

on the contrary, nine blacks had in fact been

elected to the legislature from the at-large

district between M960 and 1968. They had won on

their own strength, not as tokens appointed and

controlled by white officials. 403 U.S. at 150

n.29. These electoral victories were inconsistent

with the hypothesis that the white majority was

regularly electing slates composed solely of white

legislators catering only to white concerns.

Second, there was no evidence or finding that the

white legislators were unresponsive to the needs

and interests of their black constituents. 403

U.S. at 152, 153-4, 155 n.32. Such responsiveness

might have been expected if the political and

racial realities had resulted in an undervaluation

of black votes. Third, there was no evidence of a

history of official discrimination likely to

generate or reinforce the sort of racial attitudes

that would result in bloc voting against candi-

dates from, or supported by, the black community.

The record revealed no incidents of public or

private discrimination for several decades prior

- 43 -

to the disputed elections, and the state had had a

civil rights law since 1885. Graves v. Barnes,

343. .Z.8upp..-704, 727. n.,18 {H.D. Tex. 1972).

White v. Regester,: 412-.U.8. 7755 (1973),

presented the kind of evidence found absent in

Burns and Whitcomb. White held that the use of

multi-member districts had operated to '"cancel

out or minimize the voting strength of racial

groups’ in Bexar and Dallas counties in Texas.

There was direct evidence of bloc voting by whites

in Bexar County; oot in Dallas the existence of

bloc voting was indicated by the successful use of

"racial campaign tactics in white precincts to

defeat candidates who had the overwhelming support

of the black community." -White v. Regester, 412

B.S. .at. 767.

This direct evidence of the differing value

of black and white votes was confirmed by other

evidence. The multi-member system resulted in

near total exclusion of minority legislators.

25/ "The record shows that the Anglo—Americans

tend to vote overwhelmingly against Mexican—Ameri-

can candidates

F.Supp. at 704.

.! Craves v. Barnes, 343

-44 -

During the previous century only two blacks had

ever been elected from Dallas and only five

Mexican-Americans from Bexar county. Graves v.

Barnes, “343 VP.Supp.” at "726 n.l7, 732." This

pattern could not be explained as a result of

partisan voting; in both counties winning the

Democratic nomination usually guaranteed election

to the legislature, and the exclusion of minority

candidates had occurred in the Democratic pri-

azey 2S The district court found that the white

legislators were comparatively unresponsive to the

needs of minority residents of their districts,

White v. Regester, 412 U.S at 767, 769; it noted,

for example, that "[s]tate legislators from Dallas

County, elected county-wide, led the fight for

segregation legislation during the decade of the

1950's." Graves v, Barnes, 343 F.Supp. at 726.

All this occurred in a state with a long history

of official discrimination against blacks and

Mexican-Americans, a policy well calculated to

produce the racial bloc voting by whites of which

the plaintiffs complained. White v. Regester,

26/ No Republican had been elected to the House

from Bexar county since 1880. Graves v. Barnes,

343 F.Supp. at 731.

«45

412.U.8. ‘at 767-68; Craves v. Barnes, 343. 8S.Supp.

at:725,:726,' 727=731; :

Appellants urge that White holds only that

multi-member districts are unconstitutional

when there 1s an organized slating process which

is controlled by whites, which virtually never

slates black candidates or candidates favored by

the black community, and which effectively deter-

mines the outcome of the elections. Brief for

Appellants, pp. 8, 22, 23. But White struck down

multi-member districts in Bexar County where there

was no slating process whatever. Graves v.

Barnes, 343 F.Supp. at 731.2 he slating prac~

tices that existed in Dallas were merely symptoma-

27/ Appellants suggest that the decision regard-

ing Bexar County stemmed from the fact that there

were unconstitutional restrictions on registration

and voting by minority voters. Brief for Appel-

lants, p. 22 n.25. But those practices had ended

a year before the district court decision and two

years before the decision of this Court. Breare

v, Smith, 321 F.Supp. 1110 (5.0. Tex. 1971); Garza

v. Smith, 320 F.Supp. 131 (W.D. Tex. 1971). No

decision of this €ourt suggests that multi-member

districts should be struck down wherever there is

a recent history of discrimination in voting; such

a rule would preclude the use of such schemes in

most of the South. Had that been the rule contem-

plated by Fortson, that decision, arising in

Georgia in B64, would have struck down multi-

- 56 =

tic of the underlying racial situation, a formali-

zation of the process ordinarily achieved by white

bloc voting alone. In the absence of white bloc

voting, no slating process which systematically

excluded both minority candidates and white

candidates sympathetic to the needs of the minor-

ity community could long have survived in a county

that is 25% non-white. If White had turned on the

exclusion of blacks from the slating process --

there equivalent to election -- it would have

relied, not on Fortson, Burns and Whitcomb, but on

the prohibition against racially closed nominating

processes announced in Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S.

481 (13953),

White also recognized that the factual ques-

tions presented in such a case require "an in-

tensely local appraisal" of the evidence by the

district judge, who inevitably brings to the case

a personal familiarity with local history and

"past and present reality, political and other-

27/7 Cont'd

member districts throughout the state, since

discrimination against black voters was far more

virulent and open there and then than the prac-

tices that continued in Texas in 1970.

- 47 -

wise." #412 U.S. at 768-770. The district court

must assess the existence and impact of white bloc

voting, and weigh the significance of other less

direct evidence of dilution. White perceived that

these are issues often difficult to resolve on a

cold record.

The concept of dilution applied in White and

Whitcomb 1s neither amorphous nor unfamiliar

to this Court. The same concept has been re-

peatedly utilized by this Court in assessing

redistricting plans subject to section 5 of the

Voting Rights Act. Allen v. Board of Elections,

393 U.S. 544, 569 (1969); Perkins v. Matthews, 400

U.8. 379, 388-391 (197)); Ceorzia v., United

States, 411 U.8. 526, 1532+35:(1973); Cityiof

Richmond v. United States, 422! U.8..:358 (1975);

Beer v,. United States, 425 U.S. :130 (1976);

cf. United States v. Board of Commissioners of

Sheffield, 55 L.Ed.2d 149, 161 (1978). Georgia v.

United States relied on Whitcomb as demonstrating

that multi-member districts have ''the potential

for diluting the value of the Negro vote". 4l1

U.S. at. : 533. It relied as well on Reynolds v.

Sims, 411 U.5. at 532, as did Perkins, 400-V.8.

- 48 =

at 390. Allen, also relying on Reynolds, noted

that placing black voters in a majority white

at-large district, could "nullify their ability to

elect the candidate of their choice just as would

prohibiting some of them from voting." 393 U.S.

at 569. Such a system of electing a city govern-

ment, City of Richmond noted, '"created or enhanced

the power of the white majority to exclude Negroes

totally from participating in the governing of the

city through membership on the city council." 422

U.S.a8 371.

The uses of the dilution standard under White

and section 5, however, differ in two ways. First,

section 5 applies only to new redistricting plans

which increase the degree of dilution, Beer v.

United States, 3523 U.S. at 139-142, while White

prohibits the use of even old districting plans so

long as the degree of dilution is sufficient to

substantially undervalue black votes. Second, in

a section 5 proceeding the burden of establishing

the absence of increased dilution is on the city

or state seeking to enforce a new plan, whereas

under White the opponent of multi-member dis-

tricting bears the burden of proof.

- 49 -

Appellants apparently regard racially polar-

ized voting by white residents of Mobile, a prac-

tice at times actively encouraged by white offi-

ciate ius a: normal part’ of the political

process indistinguishable from voting on party

lines. Brief for Appellants, p. 31. Both the

Constitution and the decisions of this Court

properly treat that distinction as of paramount

importance. The franchise is a valuable right

because it can be exercised to decide "issue-

oriented elections.'" Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S.

at 159... But that right is rendered nugatory if

candidates are regularly defeated, not because of

their ideas or ideology, but because of the color

of their skin or of that of their supporters. In

- this case the record shows that the overwhelming

majority of white voters in Mobile consistently

vote against any black candidate regardless of his

9/ a ' 2 :

or her policies or merits.— That 1s a burden

which is not now, and historically rarely has

28/ Seep. 19, infra.

29/ See pp. 69-71, infra.

- 50 -

been, inflicted on any other ethnic, religious, or

national group other than blacks and Mexican-

pverieons 2 vate voters are entitled to cast

their ballots on any basis they may please,

including that of race. But they are not entitled

to have the state maximize the impact of racially

based votes by means of at-large elections.

The rule of White and Whitcomb, though

originating in Reynolds v. Sims, has several

alternative foundations. Anderson v. Martin,

375 U.S. 399 (1964), held that a state could not

"encourage its citizens to vote for a candidate

solely on account of race" by placing on its

30/ In 1960, for example, despite the immense

publicity and concern about President Kennedy's

religion, he received about 40% of the Protestant

vote. More than 1 out of 2 votes for President

Kennedy was cast by a Protestant voter. T.H.

White, The Making of the President 1960, p. 400

(1961).

- 5 {ne

ballots the race of each candidate. 375 U.S.

at 404. Neither can a state enforce an elec-

tion scheme which operates to maximize the im-

pact of racial voting by whites. Where, as here,

racial voting has its roots in a century of

officially practiced and advocated discrimination,

such a scheme perpetuates the effect of that past

discrimination ailtvann v. Charlotte Mecklenburg