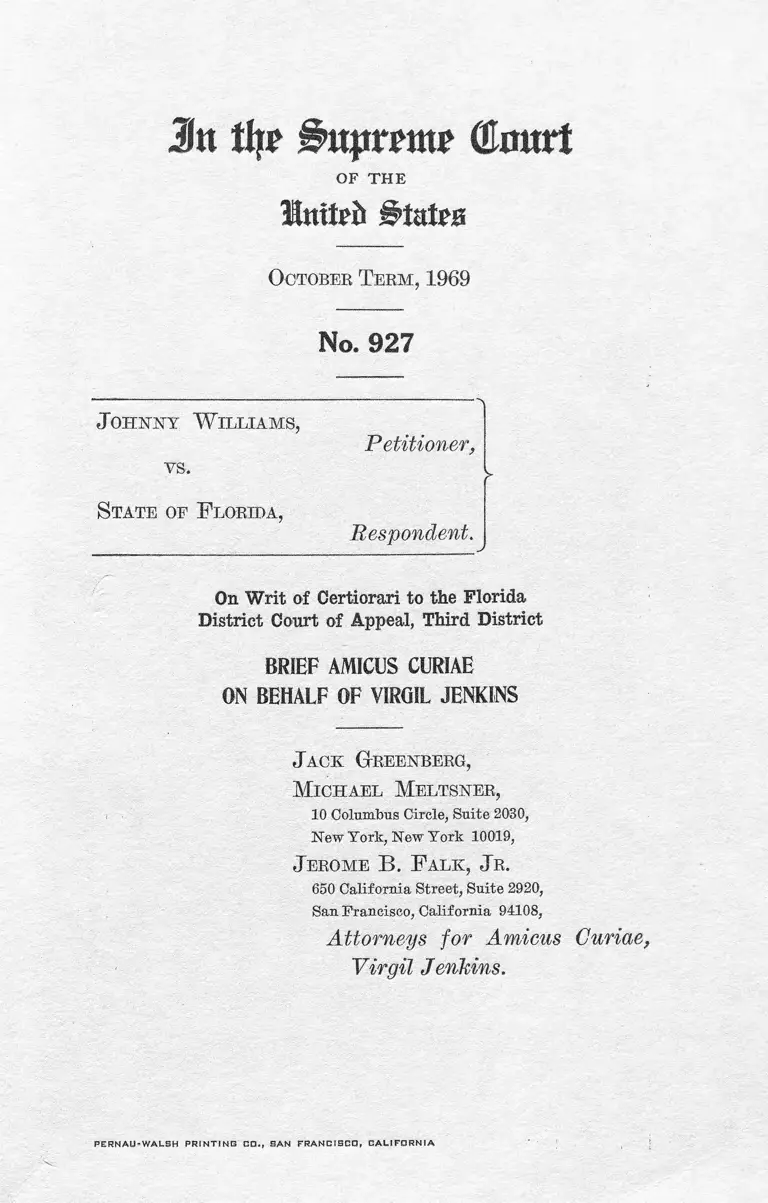

Williams v. Florida Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 20, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Williams v. Florida Brief Amicus Curiae, 1970. 05362130-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/04b6ab20-1bee-4c98-9925-a62152316339/williams-v-florida-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Jtt % i ’ujtrattp (Erntrt

OF TH E

States

October Term, 1969

No. 927

J ohnny W illiams,

VS.

State of F lorida,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Florida

District Court of Appeal, Third District

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

ON BEHALF OF VIRGIL JENKINS

J ack Greenberg,

M ichael Meltsner,

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030,

New York, New York 10019,

J erome B. F alk, J r.

650 California Street, Suite 2920,

San Francisco, California 94108,

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

Virgil Jenkins.

P E R N A U " W A L S H P R I N T I N G C D . , S A N F R A N C I S C O , C A L I F O R N I A

Subject Index

Page

Statement as to interest of amicus curiae ................ ............. 1

Summary of argument ..................................................... 6

Argument ..................... 7

Introduction ............................................. 7

I

The defendant cannot, consistently with the fifth and

fourteenth amendments, constitutionally be compelled

to disclose to the prosecution, in advance of trial,

information respecting the nature of the defense he

will or may assert .......................................................... 11

II

The defendant may not constitutionally be denied the

opportunity to offer evidence by his own testimony

on other witnesses, tending to establish his innocence,

as a penalty for noneomplianee with a notice I’equire-

ment ..................................................................................... 17

Conclusion .................... ................................................................... 27

Table of Authorities Cited

Cases Pages

Anderson v. Nelson, 390 U.S. 523. (1968) .............................. 11

Barber v. Page, 390 U.S. 719' (1968) ...................................... 18

Benton v. Maryland, 395 U.S. 784 (1969) .......................... 24

Boyd v. United States, 116 U.S. 616 (1886) ...................... 16

Cephus v. United States, 324 F.2d 893 (D.C.Cir. 1963) . . . . 12

Commonwealth v. Vecchiolli, 208 Pa. Super. 483, 224 A.2d

96 (1966) ....................................................... ......................... 8

Culombe v. Connecticut, 367 U.S. 568 (1961) ......................12, 14

Dean Milk Co. v. City of Madison, 340 U.S. 349 (1951) 22

Douglas v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 415 (1965) ......................... 18

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 ...................................... 10

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478 (1964) ......................... 13

Pay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963) ........................................... 26

Ferguson v. Georgia, 365 U.S. 570 (1961) ........ 20

T able oe A uthorities Citedii

Pages

Gardner v. Broderick, 392 U.S. 273 (1968) ...................... 11

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 (1951) ................ ............. 12

Garrity v. New Jersey, 385 U.S. 493 (1967) ...................... 11

Gori v. United States, 367 U.S. 364 (1961) .......................... 24

Griffin v. California, 380 U.S. 609 (1965) ..........................11,25

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) .................. 10

Harrison v. United States, 392 U.S. 219 (1968) .................. 23

In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967) ............................................. 18

In re Oliver, 333 U.S. 257 (1948) ......................................... 18

Klopfer v. North Carolina, 386 U.S. 213 (1967) .............. 23

Leary v. United States, 396 U.S. 6 (1969) .......................... 12

Leland v. Oregon, 343 U.S. 790 (1952) ................................ 11

Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964) ...............................9,12,13

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) .......................... 11

Morrison v. California, 291 U.S. 82 (1934) .......................... 11

Murphy v. Waterfront Commission, 378 U.S. 52 (1964) 9

Oyler v. Boles, 368 U.S. 448 (1962) ...................................... 18

People v. Rakiec, 260 App. Div. 452, 23 N.Y.S. 2d 607

(1940) ........................................................................................ 8,20

People v. Schade, 161 Misc. 212, N.Y.S. 612 (1936) . . . . 8

People v. Shulenbera, 279 App. Div. 1115, 112 N.Y.S. 2d

374 (1952) ............................................................................... 8

People v. Talle, 111 Cal.App.2d 650 (1952) ............ .............. 12

Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400 (1965) .............................. 18

Rider v. Crouse, 357 F.2d 317 (10th Cir. 1966) .............. 8

Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U.S. 534 (1961) .............................. 12

Smith v. Hooey, 393 U.S. 374 (1969) .................................. 23

Snyder v. Massachusetts, 291 U.S. 97 (1934) ...................... 9

Specht v. Patterson, 386 U.S. 605 (1967) .............................. 18

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 (1958) ............................. 11

Spencer v. Texas, 385 U.S. 554 (1967) .............................. 9,10

Spevack v. Klein, 385 U.S. 511 (1967) .............................. 11

State v. Jenkins, 203 Kan. 354, 454 P.2d 496 (1969) . . . . 4

State v. Kelly, 203 Kan. 360, 454 P.2d 501 (1969) .......... 4

State v. Kopacka, 261 Wis. 70, 51 N.E.2d 495 (1 9 5 2 ).... 8

State v. Rouriek, 245 Iowa 319, 60 N.W.2d 529 (1953) . . . . 23

State v. Smetna, 131 Ohio St. 329, 2 N.E.2d 778 (1936) 8

State v. Stump, ....... Iowa ....... , 119 N.W.2d 210 (1963).. 8, 20:

State v. Thayer, 124 Ohio St. 1, 176 N.E. 656 (1931).. .8, 20, 21

Pages

Stevens v. Marks, 383 U.S. 234 (1966) .............................. 11

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U.S. 199 ( I 9 6 0 ) . . . . 12

Tot v. United States, 319 U.S. 463 (1943) .......................... 12

Ungar v. Sarafite, 376 U.S. 575 (1964) .................................. 19

United States v. Augenbliek, 393 U.S. 348 (1969) .............. 26

United States v. Ewell, 383 U.S. 116 (1966) .................. 23

United States v. Gainey, 380 U.S. 63 (1965) ...................... 12

United States v. Housing Foundation of America, 176 F.2d

665 (3rd Cir. 1949) ................................................................. 12

United States v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570 (1968) ................ 22

United States v. Robel, 389 U.S. 258 (1967) ...................... 22

United States v. Romano, 382 U.S. 136 (1965) .................. 12

Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14 (1967) ...................18-19,26

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U.S. 49 (1949) .................................. 12

Constitutions

United States Constitution:

Fifth Amendment ................................2, 6,11,12,14, 22, 24, 26

Sixth Amendment ................................................................ 23

Fourteenth Amendment ..............................................2, 6,14, 25

Rules

Arizona Rules of Criminal Procedure 192(B) (1959) . . . . 8

Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 12 (2d Preliminary

Draft 1944) ............................................................................. 21

39 F.R.D. 272 (1966) ............................................................. 14

Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, Rule 12A, 1962 Draft,

31 F.R.D. 673 (1963) ............................................................. 21

Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure 16(c) ................. .14

Florida Rules of Criminal Procedure, Rules 1.200 ........... 2,20

New Jersey Rules, 3:5-9 (1958) .............................................. 8

Pennsylvania Rules of Criminal Procedure 312, 19 P.S.App. 8

Statutes

28 U.S.C., § 2255 .......................................................................... 2

Indiana Annotated Statute, §§ 1631-33 (1956) .................. 8

Iowa Code, § 777.18 (1962) ......................................... . 8

T able of A uthorities Cited iii

IV T able op A uthorities Cited

Pages

Kansas General Statutes Annotated, § 60-1507 .................. 2

Kansas General Statutes Annotated, § 62-1341 (1964 )... .2, 3, 8

Michigan Comp. Laws, §768.20-21 (Supp. 1966) .............. 8

Minnesota Statute, § 630.14 ...................................................... 8

New York Code of Criminal Procedure, § 295-1 (1958).. 8

Ohio Revised Code Annotated, § 2945.58 .............................. 8

Oklahoma Statute, Title 22, § 585 (1961) .............................. 8,23

South Dakota Code, § 34.2801 (Supp. 1960) ...................... 8

Utah Code Annotated, § 77-21-17 (1964) .............................. 8

Vermont Statute Annotated, Title 13, §§ 6561-62 (1959) 8

Texts

36 California State B. J. 480, 487 (1961) .......................... 15

California Law Review Comm., Recommendation and

Study Relating to Notice of Alibi in Criminal Actions

(1960) ........................................................................................ 21

The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society, 128-29 (1967) 26

Epstein, Advance Notice of Alibi, 55 J. Crim. L. C. &

P.S. 29-31 (1964) ..................................................................20,21

Epstein, Advance Notice of Alibi, p. 3 6 .................................. 23

76 Harvard Law Review, 838, 840 (1963) .......................... 14

2 Hawkins, Pleas of the Crown, 595 (8th ed. 1824) .......... 11

Millar, The Modernization of Criminal Procedure, J.

Criminal Law 344, 350 (1920) ............................................ 21

Oaks and Lehman, The Criminal Process of Cook County

and the Indigent Defendant, University of Illinois Law

Forum 584, 693 (1966) .......................................................... 26

15 Stanford Law Review 700, 701 & n. 7 (1963) .............. 23

Task Force Report, The Courts 32 (1967) .......................... 25

18 Texas Law Review 151, 156 (1940) .................................. 23

18 Texas Law Review 151 (1946) .......................................... 21

8 Wigmore, Evidence 317 (McNaughton rev. 1961) .......... 11

8 Wigmore, Evidence, § 2268, pp. 406-08 and n. 6

(McNaughton rev. 1961) ...................................................... 12

Wormuth and Mirkin, The Doctrine of the Reasonable

Alternative, 9 Utah L. Rev. 254 (1964) .......................... 22

Ju % &upmn? (ttnurt

OF THE

Intfrfr States

October T erm, 1969

No. 927

J ohnny W illiams,

Petitioner,

State of F lorida,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Florida

District Court of Appeal, Third District

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

ON BEHALF OF VIRGIL JENKINS

STATEMENT AS TO INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

Virgil Jenkins, on whose behalf this brief amicus

curiae is filed, is currently serving a 50 year sentence

in the state penitentiary at Lansing, Kansas, having

been convicted o f the crime of robbery. There has been

prepared and will shortly be filed in the District Court

of Sedgewick County, Kansas a Motion to Vacate

2

Sentence1 on behalf of Mr. Jenkins asserting, inter

alia, that his conviction was obtained in violation of

the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitution because of the invocation at his

trial of the Kansas “ alibi” statute, Section 62-1341 of

the Annotated Statutes of Kansas. He has filed this

amicus curiae brief because there is a substantial prob

ability that any decision as to the constitutionality of

Rule 1.200 of the Florida Rules of Criminal Procedure

which might be rendered in this case would also be con

trolling in his own case; moreover, as will appear, the

facts of amicus’ case demonstrate more clearly—and,

perhaps, more compellingly—than the case now before

the Court the arbitrary and unconstitutional fashion

in which alibi-notice procedures operate to infringe

rights specifically protected by the Constitution of the

United States.

Amicus was charged with participation in the rob

bery of a Wichita motel in the early hours of the

morning on July 26, 1967. He was arrested later in

the morning along with two other men; items found

on their persons and in the car in which they were

riding strongly suggested that all or some of them

were participants in the robbery.

After the conclusion of the prosecution’s ease-in-

chief, the defense at first indicated that it was not its

intention to call any witnesses. Thereafter, counsel for

1 Under Kansas procedure, a Motion to Vacate Sentence, which

is filed pursuant to Kansas Gen. Stats. A nn. § 60-1507, serves in

lieu of a petition for habeas corpus as the manner by which a

criminal conviction is collaterally attacked much as motions to

vacate under 28 U.S.C. § 2255 serve in the federal courts.

3

the defense moved to reopen the case and called de

fendant Virgil Jenkins to the stand. He proceeded to

testify that he was in a poolhall between the hours

of midnight and approximately 3:00 A.M. on the

night of the robbery, and thereafter was picked up by

one of the two other men found in the car at the time

of his arrest. The import of this testimony, of course,

was that he could not have participated in the rob

bery because, at the time of its commission, he was

somewhere else.

At this point, the prosecutor objected and moved

that the defendant’s entire testimony be striken on

the ground that it constituted an alibi, and that no

notice thereof had been given as required.2 This ob-

2Kansas Gen. Stats. A nn. § 62-1341 (1964) provides as follows:

In. the trial of any criminal action in the District Court,,

where the complaint, indictment or information charges spe

cifically the time and place of the offense alleged to have been

committed, and the nature of the offense is such as necessitated

the personal presence of the one who committed the offense, and

the defendant proposes to offer evidence to the effect that he

was at some other place at the time of the offense charged, he

shall give notice in writing of that fact to the county attorney.

The notice shall state where defendant contends he was at the

time of the offense, and shall have endorsed thereon the names

of witnesses which he proposes to use in support of such con

tention.

On due application, and for good cause shown, the court may

permit defendant to endorse additional names of witnesses on

such notice, using the discretion with respect thereto now ap

plicable to allowing the county attorney to endorse names of

additional witnesses on an information. The notice shall be

served on the county attorney as much as seven days before the

action is called for trial, and a copy thereof, with proof of such

service, filed with the clerk of the court: Provided, On due ap

plication and for good cause shown the court may permit the

notice to be served at any time before the jury is sworn to try

the action.

In the event the time and place of the offense are not speci

fically stated in the complaint, indictment or information, on

application of defendant that the time and place be definitely

4

jeetion was sustained, and Mr. Jenkins’ entire

testimony was struck. On appeal, the Kansas Su

preme Court upheld this ruling (State v. Jenkins, 203

Kan. 354, 454 P.2d 496 (1969), incorporating by ref

erence the ruling in a companion case, State v. Kelly,

203 Kan. 360, 454 P.2d 501 (1969)).3

In the: present case, Petitioner Williams had sought

from the Florida courts a pre-trial order protecting

him from disclosure of the names of his alibi wit

nesses which under Florida law were required to be

stated in order to enable him to offer evidence in support of a

contention that he was not present, and upon due notice there

of, the Court- shall direct the county attorney either to amend

the complaint or information by stating the time and place of

the offense as accurately as possible, or to file a bill of parti

culars to the indictment or information so stating the time and

place of the offense, and thereafter defendant shall give the

notice above provided if he proposes to offer evidence to the

effect that he was at some other place at the time of the offense

charged.

Unless the defendant gives the notice as above provided he

shall not be permitted to offer evidence to the effect that he was

at some other place at the time of the offense charged. In the

event the time or place of the offense has not been specifically

stated in the complaint, indictment or information, and the

Court directs it be amended, or a bill of particulars filed, as

above provided, and the county attorney advises the Court that

he cannot safely do so on the facts as he has been informed

concerning them; or if in the progress of the trial the evidence

discloses a time or place of the offense other than alleged, but

within the period of the statute of limitations applicable to the

offense and within the territorial jurisdiction of the Court, the

action shall not abate or be discontinued for either of those

reasons, but defendant may, -without having given the notice

above mentioned, offer evidence tending to show he was at some

other place at the time of the offense.

3No petition for certiorari was filed from, that ruling, Mr.

Jenkins’ counsel being of the opinion that there might be some

possible question as to whether the federal question was frilly

raised with respect to the alibi issue in the Kansas courts. For

that reason, it was decided that a Motion to Vacate Sentence

should first be brought in the trial court and, if relief should be

denied by the state courts, to then seek certiorari in this Court. It

was to that end that the pending Motion to Vacate was filed.

5

disclosed to the prosecution. Unsuccessful in that ef

fort, he complied with the requirement, presumably

on pain of the extreme sanction—exclusion of the

defendant’s evidence of an alibi—which attends to

those who fail to give the specified notice. In amicus’

case, however, notice was- never given, and as a conse

quence he was not allowed to prove that he was some

where other than at the scene of the alleged offense

at the time of its commission. Indeed, Mr. Jenkins

was not allowed to personally give testimony at Ms

own trial. (This portion of the trial transcript is repro

duced in Exhibit “ A ” herein.)

The case of amicus, then, presents a factual varia

tion from the case now before the Court; it is one, we

believe, which reveals the operation of the alibi-notice

rule, as it exists in states such as Florida and Kansas,

in its most vicious dress. Two entirely distinct consti

tutional questions are, we submit, presented by such

a provision: First, whether the State may constitu

tionally compel the defendant in a criminal case to

give the prosecution notice as to the nature of the

defense it intends to offer, together with the names

and addresses of the witnesses it intends to call in

support of that defense; and second, even if that re

quirement is constitutional, whether it may be en

forced. by excluding the evidence respecting that

defense;—including the defendant’s own testimony—as

the penalty for failure to comply with the notice re

quirement. These are substantial questions, and they

are clearly presented by the case of Virgil Jenkins.

He was not allowed to offer critical evidence/—his own

testimony—which, if believed by the jury, would have

6

compelled his acquittal. This amicus curiae brief ex

amines the constitutional questions described above

which such a practice raises in the hope that it will

further illuminate the issues now before the Court.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. It is the constitutional right of the defendant,

secured by the privilege against self-incrimination, to

refrain from assisting the prosecution in any way in

securing his own conviction. This absolute right of

silence reflects our Anglo-American notion of due pro

cess in criminal proceedings, in which the burden of

proof is imposed upon the prosecution, with the de

fendant privileged to stand moot and put the prosecu

tion to its proof. Only after the defendant has heard

the prosecution’s case against him need he decide

whether to waive that privilege and to offer evidence

of innocence. There are substantial reasons why an

innocent defendant might prefer not to do so, and it

is only after the prosecution has rested its case that

he will be able intelligently to decide whether to waive

his right of silence. The requirement that the defend

ant give advance notice of an alibi defense violates

this Due Process structure, and offends the constitu

tional protections afforded the accused by the Fifth

and Fourteenth Amendments by compelling a decision

in advance of trial as to whether an alibi defense will

be offered.

2. Even if the prosecution may compel the defense

to give advance notice of an alibi defense, it may not

7

foreclose him from offering evidence of Ms innocence

as the penalty for mere non-compliance with that re

quirement. The prosecution’s legitimate interests may

be adequately protected by other, less onerous, means

(such as a continuance of the trial) ; to deny wholly the

defendant the right to prove his innocence is a blatant

denial o f Due Process of Law.

ARGUMENT

INTRODUCTION

This case presents for decision the constitutionality

of a practice by which a defendant in a criminal case

forfeits Ms right to offer evidence of his innocence

(and, in some states Mcluding Kansas, even to testify

on his own behalf) if he has for any reason failed to

give notice of his intention to present an “ alibi” de

fense at his trial.4 In many states, this compulsory

prior notice must be accompanied by a list of the

names and addresses o f the witnesses the defense in

tends to call in support of the alibi defense.

This procedure, which compels the accused to assist

the prosecution in sealing his conviction, is at the

least a curious departure from our accusatorial tradi

tion.5 Moreover, it punishes even non-willful failures

4 At least one state, while requiring advance notice of an inten

tion to present an alibi defense, protects the interests of the pros

ecution by allowing for a continuance when the defense, without

having given notice, seeks to present evidence of an alibi but does

not prevent the defendant from making the defense. See note 22,

infra.

5Wh.ile a majority of American jurisdictions manage to do

without the alibi-notice procedure, the practice is sufficiently

widespread to justify this Court’s review. In addition to Florida,

we are aware of fifteen states having alibi-notice requirements.

8

to comply with the notice requirement with total sup

pression of what may be a controlling aspect o f the

defense. Surprisingly, its constitutionality has, until

this case, seldom been questioned. Those few reported

decisions considering challenges to the alibi statutes

have, moreover, confined their analysis to only one of

what we conceive to be two entirely separate aspects

of their constitutional infirmity; thus there has been

consideration—and rejection— of the contention that

the privilege against self-incrimination is violated by

the requirement that the accused give prior notice of

his intention to offer an alibi defense, but virtually

no consideration of whether that requirement, even

if constitutional, may be enforced by the sweeping

denial of the defendant’s right to present evidence in

his defense.6

Bight require, in addition to the notice of an intention to assert

an alibi defense, a list of witnesses the defendant intends to call.

Ariz. R. Crim. P. 192(B) (1959); Ind. A nn . Stat. §§1631-33

(1956); K an. Gen. Stat. A nn. § 62-1341 (1964); Mich. Comp.

Laws § 768.20-.21 (Supp. 1956): N.J. Rules 3:5-9 (1958): N.Y.

Code Crim. P. § 295-1 (1958); Pa. R. Crim. Pro. 312, 19 P.S.App.;

Wis. Stat. § 955.07 (1961). Seven others require only the notice as

to the intended defense. Iowa Code § 777.18 (1962); Minn. Stat.

§ 630.14 (1961); Ohio Rev. Code Ann . § 2945.58 (Page 1964);

Okla. Stat. tit. 22 § 585 (1961); S.D. Code #34.2801 (Supp.

I960); Utah Code A nn. § 77-21-17 (1964) ; V t. Stat. A nn. tit.

13, ■§§ 6561-62 (1959).

6The principal decisions of which we are aware are Rider v.

Crouse, 357 F.2d 317 (10t.h Cir. 1966); State v. Stum p,..... Iowa

..... , 119 N.W.2d 210 (1963); State v. Smetna, 131 Ohio St. 329,

2 N.E.2d 778 (1936); State v. Thayer, 124 Ohio St. 1, 176 N.E.

656 (1931) (with three judges expressing the view that the alibi

statute is unconstitutional); People v. Shulenberg, 279 App. Div.

1115, 112 N.Y.S.2d 374, 375 (1952); People v. Rakiec, 260 App.

Div. 452, 23 N.Y.S.2d 607, 612-13 (1940) (holding, however, that

the statute does not apply to the testimony of the defendant but

only to other witnesses); People v. Schade, 161 Misc. 212, 292

N.Y.S. 612, 615-19 (1936); Commonwealth v. Vecchiolli, 208 Pa.

Super. 483, 224 A.2d 96 (1966); State v. KopacJca, 261 Wis. 70,

51 N.E.2d 495, 497-98 (1952).

9

W e think it particularly fitting that at this time the

Court undertake a review of the entire question.

There appears to have been no really serious canvass

ing of the constitutionality of these alibi statutes

since this Court made applicable to state criminal pro

ceedings. the protections of the Fifth Amendment

privilege against self-incrimination.7 Moreover, recent

developments of constitutional doctrine put into

clearer perspective the basis of the constitutional

claim which, as noted, has never been adequately can

vassed by the lower courts—whether the defendant

may be wholly disabled from presenting evidence

(sometimes, as in the case of amicus, including his

own testimony)8 establishing a vital defense, simply

because of his failure to comply with a procedural

requirement that he give prior notice of that defense.

Perhaps it is well to preface our analysis with the

observation that we do not urge the Court to test this

Florida procedure by a subjective standard of fair

ness. To be perfectly candid, Spencer v. Texas, 385

U.S. 554 (1967) makes it abundantly clear that an

argument premised upon subjective notions of fair

ness bears a heavy burden. W e disclaim any intention

to appeal merely to what some may think “ to be

fairer or wiser or to give a surer promise of protec

tion to the prisoner at bar.” Snyder v. Massachusetts,

291 U.S. 97, 105 (1934). Nor even do we rely on “ the

traditional jurisprudential attitudes of our legal sys-

7Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964); Murphy v. Waterfront

Commission, 378 U.S. 52 (1964).

8In some jurisdictions, including Florida, the defendant’s own

testimony would not be excluded for failure to give the required

notice but only that of other witnesses. See note 17, infra.

10

tern” which the dissenters in Spencer thought invali

dated the Texas recidivist procedure upheld in that

case. 385 U.S. at 570. In our view, the case against

Florida's alibi statute and its counterparts in other

jurisdictions is premised on specific and well-estab

lished constitutional guarantees. Thus this case need

not be an occasion for reopening the always fascinat

ing debate between those who believe that this Court’s

jurisdiction over state criminal procedures is limited

“ to specific Bill of Rights’ protections” (Duncan v.

Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145, 171 (Black, J., concurring) )

and those who conceive a limited jurisdiction under

the Due Process Clause for the protection of substan

tive “ personal rights that are fundamental” ( Griswold

v. Connecticut, 381 U.S, 479, 486 (1965) (concurring

opinion)) or to deal with assertedly unfair criminal

procedures “ fundamentally at odds with traditional

notions of due process . . . [which] needlessly '[pre

judice] the accused without advancing any legitimate

interest of the State.” Spencer v. Texas, supra, at 570

(dissenting opinion). Whatever one’s conception o f the

reach of the Due Process Clause in such matters, alibi

statutes such as Florida’s cannot stand, for they violate

specific, established constitutional guarantees. W e

turn to an analysis of that infringment.

11

I

THE DEFENDANT CANNOT, CONSISTENTLY WITH THE FIFTH

AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS, CONSTITUTIONALLY BE

COMPELLED TO DISCLOSE TO THE PROSECUTION, IN AD

VANCE OF TRIAL, INFORMATION RESPECTING THE

NATURE OF THE DEFENSE HE WILL OR MAY ASSERT

This Court has had frequent occasion to recall that

ours is an accusatorial system and that, unlike the sys

tems of some other countries, the defendant in a crim

inal case need do nothing whatever which might in

any way lead to his conviction. The prosecution must

“ shoulder the entire load” (8 W igmore, Evidence 317

(McNaughton rev. 1961), quoted in Miranda v. Ari

zona, 384 U.S. 436, 460 (1966)); the defendant may

not be made, in Hawkins’ oft-quoted phrase, “ the de

luded instrument of his own conviction” . 2 Hawkins,

P leas of the Crown 595 (8th ed. 1824). Its origins

may be complex and imperfectly understood; but the

Fifth Amendment, now fully applicable to state pro

ceedings,9 clearly reflects not only values fundamental

bo our system of criminal law but also the very struc

ture o f that system. The prosecution bears the burden

of independent investigation, of going forward, and

of proving the defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable

doubt (Morrison v. California, 291 U.S. 82 (1934) ;

Leland v. Oregon, 343 U.S. 790, 805-6 (1952) (Frank

furter, J., joined by Black, J., dissenting) ; of. Speiser

v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513, 526 (1958) ( “ Due process

9gee authorities cited note 7 supra; see also Gardner v. Brod

erick, 392 U.S. 273 (1968); Spevack v. Klein, 385 U.S. 511

(1967)- Garrity v. New Jersey, 385 U.S. 493 (1967); Stevens v.

Marks, ’ 383 U.S. 234 (1966); Griffin v. California, 380 U.S. 609

(1965); Anderson v. Nelson, 390 U.S. 523 (1968) (per curiam).

12

commands that no man shall lose his liberty unless

the Government has borne the burden of producing

the evidence and convincing the fact-finder of his

guilt.” ) ) , unassisted by any irrational presumptions

(see Tot v. United States, 319 U.S. 4.63 (1943) ; United

States v. Romano, 382 U.S. 136 (1965) ; Leary v.

United States, 395 U.S. 6 (1969); compare United

States v. Gainey, 380 U.S. 63 (1965). The defendant

bears no duty to prove his innocence. Cf. Garner v.

Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 (1951); Thompson v. City of

Louisville, 362 U.S. 199 (1960). The defendant may

not be compelled to testify; indeed, he may not even

be called by the prosecution to the witness stand and

asked whether he wishes to testify.10

This structure, and the allocation o f burdens which

it reflects, is fundamental to our jurisprudence. Here

basic principles o f Due Process (see Watts v. Indiana,

338 U.S. 49, 54-55 (1949) (plurality opinion);

Ctilombe v. Connecticut, 367 U.S. 568, 581-83 (1961)

(plurality opinion) ; Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U.S. 534,

540-41 (1961) have become “ assimilated” (Cidombe

v. Connecticut, supra, at 583, n. 25) with the Fifth

Amendment privilege against self-incrimination. See

Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964). Consistently

these cases reflect

“ recognition that the American system of crimi

nal prosecution is accusatorial, not inquisitorial,

and that the Fifth Amendment privilege is its

10VIII WiGMORE, Evidence § 2268, pp. 406-08 and n. 6

(McNaughton rev. 1961); Cephus v. United States, 324 F.2d 893

(D.C.Cir. 1963); United States v. Housing Foundation of Amer

ica, 176 F.2d 665 (3d Cir. 1949) ; People v. Talle, 111 Cal.App.2d

650 (1952).

13

essential mainstay. . . . Governments, state and

federal, are thus constitutionally compelled to es

tablish guilt by evidence independently and freely

secured, and may not by coercion prove a charge

against an accused out o f his own mouth.” (Mal

loy v. Hogan, supra, at 7-8).

The requirement that a defendant give notice to the

prosecution of his intention to assert an alibi defense

flies in the teeth o f these principles. It compels him

to become an unwilling aide to the prosecution, pro

viding it with information which may assist in his

conviction. The prosecution, at the point in the pro

ceedings, when the defendant is required to give no

tice o f an alibi defense, has progressed far beyond

merely having “ focused” on the accused ( cf. Escobedo

v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478, 491 (1964)); the defendant

is the target of a determined, adversary deployment

of the state’s substantial resources in an effort to con

vict and imprison him. That complex of values safe

guarded by the Fifth Amendment is infringed when

he can be required to offer the slightest assistance to

his adversary.

Moreover, disclosure o f a potential alibi defense

prior to trial forces the defendant to decide what he

has not previously been required to decide until after

the prosecution has been put to its proof: whether he

will stand mute, exercising his constitutional right of

silence, or whether he will present evidence—and,

possibly, personally testify—by way of defense.

The principal argument for pretrial notice rests on

the assertion that the defendant is in no way forced

14

to waive his constitutional right to remain silent in

the face o f charges against him, but is only required

to accelerate the timing of that decision. But in our

view of the adversary process enshrined in the Fifth

and Fourteenth Amendments, it is precisely the de

fendant’s right, to defer that decision until after he

has heard the State’s case against him.11 While he

may ultimately elect to offer evidence and testify, the

prosecution cannot compel him to do so, or accelerate

the timing of his decision as, for example, by calling

him to the witness stand. See authorities cited in note

10, supra. To advance the time at which the defend

ant must decide whether to raise an alibi def ense vio

lates this principle.

The violation of constitutional principles is any

thing but theoretical; it can work a considerable un

fairness. The defendant may wish to avoid reliance

on the alibi defense, if possible;12 but often it will

1]lThat right, as we view it, is a component of the Fifth

Amendment privilege against self-incrimination, though obviously

it might equally be viewed as a basic principle of procedural due

process. Note, 76 Harv. L. Rev. 838, 840 (1963). As Mr. Justice

Frankfurter noted in Culombe v. Connecticut, supra, Due

Process principles and the privilege have, in this area, become

“ assimilated/’ See pp. 12-13, supra.

12In this respect, the present case differs from the question

which is presented by general pretrial discovery against the de

fendant in a criminal case which is allowed as the price for grant

ing the defendant discovery against the prosecution. See, e.g.,

F ed. R.Crim.Pro. 16(c). While the constitutionality of that prac

tice is by no means beyond dispute (see, e.g., Statement of Mr.

Justice Douglas, dissenting from the transmittal of the 1966

amendments to the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, 39

F.R.D. 272 (1966), it can arguably be defended on the ground that

the defendant, by obtaining discovery against the prosecution, can

at least determine in advance of trial the nature of the case against

him and is thus in a position to make the kinds of decisions he

15

only after the prosecution has closed its case be in a

position to judge whether he must run the risks which

that defense entails,13 But compliance with the alibi

statute may well compel the defense to put in its alibi

evidence even though, after consideration of the prose

cution’s case, it would prefer not to do so. This fol

lows even though the statute itself does not in terms

require the defense to introduce the alibi evidence

which was the subject of its notice to the prosecution,

otherwise could only make after hearing the prosecution’s case-in-

chief at trial.

It is somewhat ironic that one of the principal arguments fre

quently heard against allowing discovery against the prosecution

in a criminal case—-fear that the prosecution’s witnesses will be

harassed—has not caused comparable pause among the proponents

of alibi-notice statutes. Yet there is ample reason for concern. No

tice to the prosecution of an intention to rely on an alibi defense

will predictably result in the questioning by the prosecutor (or by

police officers acting under his direction) of the witnesses specified

by the defendant- as those he intends to call. Even restrained ques

tioning by the prosecutor or his agents may frequently have a

coercive impact upon the sorts of individuals of modest background

who so frequently will be the basis of an alibi defense. It was pre

cisely this concern that persuaded the California Bar Association to

oppose an alibi-notice proposal (see note 19 infra) “ on the ground

that [this] would cause, the harassment a.nd intimidation of alibi

witnesses by public officers,” (36 Cal State B. J. 480, 487.

(1961).

lsThe nature of those risks will, of course, vary from case to

case. For example, (1) the witnesses on which the defendant

would have to rely might be weak or particularly vulnerable to

impeachment by proof of pifior felony convictions; (2) estab

lishment of the alibi might require testimony by the defendant

himself, and thus a waiver of his privilege with the resulting sub

jection to impeachment through evidence of prior felony convic

tions; (3) the alibi might itself require the admission of another—

uncharged— crime, or (in the case of a defendant on parole or

probation) admission of conduct constituting violation of condi

tions of parole or probation; or (4) the alibi, though meritorious,

may because of the nature of the evidence available to the de

fendant be potentially unbelievable; a cautious lawyer may be

reluctant to present to the trier of fact evidence it is not likely to

accept, with the resultant destruction of the credibility of the

entire defense.

16

for it will often be the case that the prosecution, in

presenting its opening statement or case-in-chief, will

have anticipated the defense in some manner which

will as a practical matter compel the defense to fol

low through with the alibi defense lest the jury draw

an unfavorable: inference from its failure to do so.

Even if the potential prejudice to the defendant

were considerably less apparent, this alibi-notice pro

cedure would be cause for grave concern. As the Court

said in a similar context of the need for vigilance

where Fifth Amendment interests are concerned, “ il

legitimate and unconstitutional practices get, their first

footing . . . by silent approaches and slight deviations

from legal modes of procedure.” Boyd v. United

States, 116 U.S. 616, 635 (1886).

But for the reasons already mentioned, the prejudice

is substantial. As a consequence of some of those con

siderations, a defendant considering reliance upon evi

dence establishing an alibi may feel compelled to fore

go that defense rather than give advance notice to the

prosecution in compliance with the statute. Failure to-

do so in nearly all of the states having alibi rules will,

however, prevent the defendant from changing his

mind once the prosecution has rested; he is forever

barred from, introducing evidence,—often including, as

we have earlier noted, his own personal testimony—of

an alibi. Similarly, fear of that terrible sanction may

compel such a defendant to give notice of the alibi

before he is in fact in a position to decide intelligently

whether to make that decision. That obviously was the

17

case here. For that reason, we must now turn to an

examination of the constitutionality of that sanction.

II

THE DEFENDANT MAY NOT CONSTITUTIONALLY BE DENIED

THE OPPORTUNITY TO OFFER EVIDENCE, BY HIS OWN

TESTIMONY ON OTHER WITNESSES, TENDING TO ESTAB

LISH HIS INNOCENCE, AS A PENALTY FOR NONCOMPLI

ANCE WITH A NOTICE REQUIREMENT

Even assuming- what we do not concede, namely,

that the State may constitutionally require a defend

ant to give the prosecution prior notice of his inten

tion to offer an alibi defense along with the names

and addresses o f the witnesses he intends to call—

this Florida procedure could not stand. For Florida,

as do most (though not a ll)14 of the States having

alibi statutes, enforces that procedural requirement

by denying defendants their right to present evidence

o f an alibi defense as to which they were required

but failed to give notice. Our submission, stated sim

ply, is that a defendant in a criminal case has no

more fundamental constitutional right than the right

to offer evidence'—and testify, if he wishes—on the

issues which the applicable law makes relevant in the

case. This right the State may not abridge—indeed,

wholly deny—for merely failing to comply with a pro

cedural requirement whose benefits are, at the least,

minimal and which in any event can be fully vindi

cated by means far less subversive o f the defendant’s

Due Process rights. i

i4See infra note 22 and accompanying text.

18

The right to be heard in defense against criminal

charges is anything but. an exotic constitutional crea

tion at the penumbra of contemporary jurisprudence.

To the contrary, it is so fundamental that few would

dispute; its constitutional stature; a literally unbroken

stream of decisions o f this Court (paralleled, of

course, by decisions o f courts throughout this coun

try) have affirmed that, at a minimum, Due Process

requires that a defendant in a criminal case “ be pres

ent with counsel, have an opportunity to be heard, be

confronted: with witnesses against him, have the right

to cross-examine, and to offer evidence of his own.”

Specht v. Patterson, 386 U.S. 605, 610 (1967) ;

see also In re Oliver, 333 U.S. 257, 273-77 (1948)

( “ due process of law . . . requires that [the defend

ant] . . . have a reasonable opportunity to meet [the

charges] by way of defense or explanation . . . and

call witnesses in his behalf, either by way of defense

or explanation” ) ; Oyler v. Boles, 368 U.S. 448 (1962) ;

In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967). The recent decisions

o f this Court specifically applying the various Sixth

Amendment protections to State criminal proceedings

add emphasis to the constitutional stature of the right

to offer defensive evidence. They establish that the

accused cannot be deprived of the opportunity to

cross-examine the witnesses against him13 and, more

importantly for present purposes, neither may he be

denied the right to compulsory process for obtaining

witnesses whose testimony might be favorable. Wash

isPointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400 (1965); Douglas v. Alabama,

380 U.S. 415 (1965); Barber v. Page, 390 U.S. 719 (1968).

19

ington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14 (1967). Similarly, the

defendant’s right to effectively defend against the

charges against him, and to offer evidence of his in

nocence, may not be indirectly infringed by an un

reasonable denial of a continuance. TJngar v. Samftte,

376 U.S. 575, 589 (1964).

One need only contrast these imcontradicted expli

cations of a fundamental constitutional principle with

the typical application of an alibi rule of the sort

which Florida has adopted to perceive the grave

constitutional difficulties presented by such a pro

cedure. The case of amicus is instructive. Charged

with participation in an armed robbery perpetrated

by several individuals, he took the stand to testify

that he was: elsewhere—in a poolroom to be specific—

at the time of the alleged offense. That testimony was

of the gravest importance; if believed by the jury, it

would have compelled his acquittal. His counsel, for

reasons never disclosed on the record, had not given

notice of the possible defense of alibi as Kansas law

requires, and amicus’ testimony was interrupted by

an objection of the prosecutor, which was sustained.

The defendant’s testimony was thus abruptly termi

nated, and the jury instructed that it must disregard

the defendant’s protestations that he was elsewhere

at the time the alleged offense occurred.16 Thus in

amicus’ case, the denial of elementary due process

was compounded by the trial court’s order barring

the defendant himself from testifying as to facts

16An excerpt from the trial transcript of amicus containing

this portion of the trial is attached hereto as Appendix “ A ” ,

20

which would establish his innocence. Cf. Ferguson v.

Georgia, 365 U.S. 570 (1961).17

W e doubt that any justification exists for the out

right denial o f the right to offer evidence—indeed,

to testify personally—at the trial on an issue which

is not only relevant under the applicable law but is

in fact potentially dispositive of the outcome of the

case. But even if we were to accept that this most

fundamental right might be weighed against some

overriding, compelling state interest, no such counter-

veiling considerations are present to justify the appli

cation of so sweeping a denial o f constitutional rights

for mere non-compliance with a technical requirement

of notice.

The purpose which alibi statutes or rules such as

the one before the Court are intended to serve—

avoidance of surprise and perjurious testimony—is

unobjectionable (although there is, for the reasons

stated in Part I, supra, considerable doubt as to the

State’s constitutional power to achieve that goal by

compelling the accused to give notice to it prior to>

trial). Most of these provisions stem from proposals

made a number of years ago (see Epstein, Advance

Notice of Alibi, 55 J. Ck im . L.C. & P.S. 29-31

(1964)), at a time when the federal Constitution had

not been thought to impose much restraint upon state

17Some states, including Florida, would not bar the defendant

from testifying even though no notice was given, but would bar

other witnesses. E.g., F la.R. Crim. Pro. 1.200; State v. Stump,

......... Iowa ..... , 119 N.W. 2d 210 (1963); State v. Thayer, 124

Ohio St. 1, 176 N.E. 606 (1931); People v. Rakiec, 260 App.

Div. 452, 23 N.Y.S. 2d 607 (1940). Kansas is not so generous.

21

criminal proceedings. The proponents of the alibi-

notice procedure contended that the cause o f justice

would be well served by requiring the accused to give

advance notice to the prosecution of its intention to

raise an alibi defense; the prosecution might then

have an adequate opportunity to investigate the facts

o f the defense and develop evidence o f its own which

might disprove it. E.g., State v. Thayer, supra;

Millar, The Modernisation of Criminal Procedure, J.

Crim . L. 344, 350 (1920). Some doubt has been ex

pressed as to the necessity and efficacy o f the notice

requirement,18 and barely more than a quarter o f the

States have adopted it ;19 further, as will be seen, not

all o f them routinely deny the accused his right to

offer evidence of a critical defense as the penalty for

noncompliance, but rather attempt to enforce that

policy of disclosure by other means. See note 22, infra,

and accompanying text.

With the merits of and the necessity for the alibi-

notice procedure supported by somewhat less than

overwhelming evidence,, it is appropriate to consider

lsSee, e.g., Note, Is Specific Notice of the Defense of Alibi

Desirable? 18 Tex.L.Rev. 151 (1946).

19Proposals for an alibi-notice requirement have recently been

made but not accepted in California (see Calif. Law Rev. Comm.,

Recommendation and Study Relating to Notice of A libi in

Criminal A ctions (I960)) and in the federal criminal system (see

Proposed Rule 12A, Fed.R.Crim.Pro., 1962 Draft, 31 F.R.D. 673

(1963)); that was the second occasion on which an alibi-notice

requirement was rejected for the federal criminal system, as this

Court in 1944 struck two alternate alibi provisions from the then

proposed Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. Epstein, 'Advance

Notice of Alibi, 55 J. Crim. L.C. & P.S. 29, 30 (1964). See F ed.R.

Crim.Pro. 12 (2d Preliminary Draft 1944).

22

whether those limited advantages might adequately

he secured without depriving the defendant of his

constitutional right to be heard and to offer evidence

tending to establish his innocence. E.g., United States

v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570, 582-83 (1968); United States

v. Bobel, 389 U.S. 258, 268 (1967); Dean Milk Co. v.

City of Madison, 340 U.S. 349, 354-56 (1951); see

generally Wormuth and Mirkin, The Doctrine, of the

Reasonable Alternative, 9 U t a h L . R e v . 254 (1964).

Such an examination, we submit, convincingly demon

strates that the goal of preventing unjustifiable ac

quittals because o f the prosecution's inability to dis

prove perjurious alibi defenses can adequately be

protected by means far less destructive of cherished

constitutional guarantees.20 W e consider some of them

briefly:

(1) The trial court might punish the wilful disr

egard of an applicable rule of procedure by contempt

—-of either the accused, his counsel, or both. This

assumes, of course, that the prosecution has a right

to such notice, an assumption which is disputed in

Part I, supra. But if the requirement of notice is

constitutional, then neither the defendant nor his.

counsel should be immune from the imposition of

20Some of these alternatives would assist in encouraging the de-

fense to give prior notice of an intended alibi defense; thus their

constitutionality turns on whether the defendant can be compelled

to give any such notice. See Part I, supra. As noted, there are

grave constitutional doubts as to the constitutionality of that re

quirement, and some of the alternatives which we are about to

consider (e.g., continuing the trial) suggest that, if the Fifth

Amendment question also turns on the availability of a less onerous

alternative, such an alternative would not be difficult to find.

23

sanctions in the manner by which courts have tradi

tionally protected their substantial interest in orderly

procedure.

(2) The trial court might, where the prosecution

has been surprised by the unannounced raising of an

alibi defense, continue the trial for a reasonable

period to allow the prosecution to make whatever

investigation might be necessary to enable it to meet

the defense.21 In at least one state,22 the trial court is

empowered to continue the trial where an alibi de

fense is raised without prior notice, but does not have

the power to exclude evidence of alibi. It is difficult

to conceive of a situation in which the legitimate

interests of the prosecution would not fully be pro

21The right of speedy trial, now a constitutional protection ap

plicable to state criminal proceedings (Klopfer v. North Carolina,

386 U.S. 213 (1967); Smith v. Hooey, 393 U.S. 374 (1969)), would

in no way be offended by a brief continuance for this purpose. The

Sixth Amendment protects only against “ undue and oppressive”

delays (United States v. Ewell, 383 U.S. 116, 120 (1966)), and not

against those which are justifiable and reasonable. See, e.g., Har

rison v. United States, 392 U.S. 219 (1968). There could be no

reasonable basis for complaint where the defendant’s own failure

to comply with the statute or rule requiring notice was the occasion

for granting a continuance.

22See Okla. Stat., Tit. 22, §585 (1961). Iowa has a similar statute,

but there is judicial authority allowing exclusion of the alibi evi

dence. See State v. Bourick, 245 Iowa 319, 60 N.W.2d 529 (1953).

Most states, but apparently not Kansas, at the least allow the trial

judge discretion to allow the evidence and protect the interests of

the prosecution by other means such as continuance. See Note, 15

Stan. L. R ev. 700, 701 & n. 7 (1963). Moreover, there is some

evidence that even in those states wdiich by statute absolutely bar

alibi evidence where notice should have been but was not given,

trial judges ameliorate the harshness of that provision by ignoring

it. See Note, Is Specific Notice of the Defense of Alibi Desirable?, 18

Tex. L. Rev. 151, 156 (1940); see Epstein, Advance Notice of Alibi,

supra, at 36.

24

tected by a continuance, the granting o f which might

even be made mandatory lest there be any doubt as

to the willingness of trial judges to grant continu

ances in the circumstances.

(3) Should the defendant fail to give the required

notice (and, again, assuming that the requirement is

constitutional), that violation might be a proper basis

for declaring a mistrial in circumstances (which, pre

sumably, would be exceedingly rare) in which simply

ordering a continuance would not be adequate to

protect the legitimate interests of the prosecution.23

(4) The prosecutor might be allowed to argue to

the jury where the facts warrant, that the surprise

assertion o f an alibi defense (in violation o f the re

quirement that he give advance notice) prejudiced the

State’s ability to deal with that defense and, more

over, must be viewed critically in view of the circum

23While the ordering of a mistrial could in theory give rise to a

claim that a retrial would constitute jeopardy in violation of the

Fifth Amendment (Benton v. Maryland, 395 U.S. 784 (1969)),

such a contention would seem ill founded. See Gori v. United

States, 367 U.S. 364 (1961). Such a ease would not involve any of

the factors which might render a retrial following a mistrial as a

violation of the double jeopardy clause, such as a mistrial ordered

because of wrongful conduct on behalf of the prosecution or where

the purpose of the trial judge was to “ help the prosecution, at a

trial in which its case is going badly, by affording it another, more

favorable opportunity to convict the accused.” (Id., at 905). To

the contrary, our hypothetical mistrial would be the response to the

defendant’s failure to comply with the requirement that he give

advance notice of an alibi defense, in the rare case where no other

remedy would suffice. Particularly when viewed as an alternative

to the* far harsher procedure presently practiced— exclusion of the

defendant’s alibi evidence altogether— such an order should not be

deemed a denial of due process. In any event, it would be a highly

unusual case in which the other alternatives discussed above would

not fully protect the interests of the prosecution.

25

stances.24 Similarly, an instruction to that effect from

the trial judge might be in order.

The foregoing alternatives-—which may well be con

siderably short o f exhaustive—-would, singly or in

combination, provide full protection for the legitimate

interests of the prosecution which are said to be the

basis for the alibi-notice requirement. There is, plainly

and simply, no possible justification for a sanction

which wholly denies the opportunity to be heard on

a vital aspect o f his defense. The alibi-notice provi

sions of Florida and Kansas—and the other jurisdic

tions which similarly deny the defendant the right to

be heard—are fundamentally arbitrary, viciously

choking off the defense as a penalty for what is at

most a procedural omission.

The unfairness o f that approach is particularly

apparent when viewed against the background of the

realities of criminal law’ administration in this coun

try. A substantial number of defendants in criminal

cases are indigent or nearly so. They may be repre

sented by court appointed counsel, a Public Defender,

or one o f the attorneys whose office is the local crimi

nal court and whose practice is operated, as the recent

Presidential Crime Commission’s Task Force on the

Administration of Justice phrased it, on “ a mass pro

duction basis.” Task F orce R eport: T he Courts 32

(1967). Frequently, counsel will have had little or no

opportunity to study the case much in advance o f trial;

24Such a comment would not violate the rule of Griffiin v. Cali

fornia, 380 U.S. 609 (1965) if, contrary to the argument of Part I,

supra, the alibi-notice requirement is not held to violate the Fifth

and Fourteenth Amendments.

26

it is not uncommon for client and. counsel to meet

just before the trial.25 Inadvertanee or the errors of

counsel may account for a substantial proportion of

the instances in which the required notice is not given

and the alibi defense thereby lost forever; but it is

the defendant, not his lawyer, who must pay the price.

Compare Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391, 439 (1963). Thus

a penalty—the loss o f the right to present an alibi

defense— which would be unfair even as to a defend

ant who deliberately concealed his intention to present

an alibi defense is also indiscriminately applied to the

non-wilful defendant who, perhaps through the blun

ders of counsel or due to his late entry into the case,

fails to give the required notice.26

25See, e.cj., Oaks and Lehman, The Criminal Process of Cook

County and The Indigent Defendant, 1966, Univ. op III. L. F orum,

584, 693 (1966); The Challenge of Crime in a F ree Society, 128-

29 (1967):

In many lower courts defense counsel do not regularly ap

pear, and counsel is either not provided to a defendant who

has no funds; or, if counsel is appointed, he is not compensated.

The Commission has seen, in the “ bullpens” where lower court

defendants often await trial, defense attorneys demanding

from a potential client the loose change in his pockets or the

watch on his wrist as a condition of representing him. Attor

neys of this kind operate on a mass production basis, relying on

pleas of guilty to dispose of their caseload. They tend to be

unprepared and to make little effort to protect their clients’

interests.

26This case involves the baldest of infringements of the right of

an accused to be heard and to present evidence. Recognition of the

unconstitutionality of that infringement surely does not imply that

a federal question would be presented by the even-handed applica

tion of traditional rules of evidence as to admissibility, any more

than the application of the Sixth Amendment right of confrontation

to state criminal proceedings (see authorities cited note 15, supra)

has superseded state hearsay rules with a federal evidence code (cf.

United States v. Augenblick, 393 U.S. 348, 355-56 (1969)), or the

right to compulsory service of process supersedes “ nonarbitrary

state rules” regarding the capacity of a witness to testify. Wash

ington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14, 23 n.21; see also id., at 24-25 (Harlan,

J., concurring).

27

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated in Part I of this brief, the

prosecution is not entitled to the assistance of the de

fense in the preparation of its case for trial, and may

not require him to give notice o f and information

about the intended defense. The defendant has a

constitutional right to defer its decision as to reliance

upon an alibi defense until after he has heard the

prosecution’s case against him.

Moreover, even if the defendant can constitutionally

be compelled to give such notice, he may not be

deprived o f his constitutional right to be heard and

to present relevant evidence tending to establish his

innocence for mere non-compliance with the notice

requirement; the prosecution’s legitimate interests

may adequately be protected by means far less subver

sive o f the defendant’s rights.

For these reasons, the conviction of the petitioner

should be reversed.

Dated: January 20, 1970.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg,

Michael Meltsner,

J erome B. F alk, J r.

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae,

Virgil Jenkins.

(Appendix “ A ” Follows)

Appendix “ AM

Appendix “ A ”

EXCERPT FROM THE TRIAL TRANSCRIPT OF THE STATE OF

KANSAS VS. THOMAS KELLY AND VIRGIL JENKINS, CASE

NO. CR 4276-67, DISTRICT COURT OF SEDGWICK COUNTY,

KANSAS, DIVISION SIX, OCTOBER 30, 1967, pp. 155-161:

The Court: The defendant, Mr. Jenkins, has indi

cated that he would like to testify in his own behalf.

The Court: All right, bring the jury in, Mr.

Knott.

The B ailiff: Jury is all present and accounted for,

Your Honor.

The Court.: Very well, Mr. Knott. Do you wish to

make an announcement, Mr. Hayes?

Mr. Hayes: Yes, Your Honor, the defense moves

to reopen its case and would like to present evidence

to the court and jury.

The Court: Very well. Do you have any objection,

Mr. Focht %

Mr. Focht: No, Your Honor.

The Court: Very well, the case will be reopened.

Before proceeding, Mr. Hayes, I wish to advise the

jury that the State of Kansas and the defendants

have entered into the following stipulation: That on

the night in question, July 26, July 25th, 1967, the

1965 Mustang in question was titled in the name of

Burney Henderson Smith, that at the time the auto

mobile was stopped on July 26, 1967, the driver of

the automobile was Burney Henderson Smith.

Your witness, Mr. Hayes.

Mr. Hayes: The defense will call Mr. Jenkins.

n

The Court: Very well. Mr. Jenkins, will you come

forward, sir?

V IR G IL JENKINS

called as a witness; on his own behalf, after having

first been duly sworn, testifies as follows:

Direct Examination

by Mr. Hayes:

Q. State your name and address for the court,

please ?

A. Virgil Jenkins.

Q. And where were you residing on the 25th o f

July, 1967?

A. 3212 Olive, Kansas City, Missouri.

Q. Now, did you on about the 26th of July, 1967,

come to the City o f Wichita?

A. Yes.

Q. And what mode of transportation did you

come?

A. ’65------

The Court: Excuse me, gentlemen. I would like

to have counsel approach the Bench, please. Have you

advised Mr. Jenkins that he doesn’t have to testify?

Mr. Hayes: I ’ll do so in my examination. Of

course, he knows; I have talked to him about it.

The Court: Well, let’s do it in your examination.

Q. (By Mr. Hayes) You understand, sir, you

don’t have to testify in your own behalf ?

A. Yes.

Q. You understand that. You could invoke the

Fifth Amendment and thereby exempt yourself from1

any testimony in this case?

m

A. Yes;, sir.

Q. Is it your desire to freely—is it your free and

voluntary desire to testify in this case in your own

behalf ?

A. Yes.

Q. And do you understand that by doing so you

waive the Federal immunity?

A. Yes.

Q. And subject yourself to------

A. Yes.

Q . ------ questions?

The Court : You understand also, Mr. Jenkins,

that anything you say will be, can and will be used

against you?

A. Yes.

The Court: All right.

Q. (B y Mr. Hayes) Do you also understand, Mr.

Jenkins, that anything you say may be held against

you or for you? I appreciate that.

A. Yes.

Q. All right. What mode of operation was used

to come to the City of Wichita?

A. 1965 Mustang.

Q. How, would you tell the court in your own

words what happened after you arrived in the City

of Wichita?

A, Well, we got here about 9, about 9 o’clock be

cause we had car trouble. There were four of us at

the time, Burney Smith, Thomas Kelly, a guy named

McGee, and myself. We were supposed to come down.

Smith, he had some, kin down here. Well, my folks

stayed here, and I wasn’t working down here, and

iv

Mr. Kelly decided to come down with us, so we rode

around for a while and started to drinking. Me and

Kelly got out on—there is a pool hall between W a

bash and Ohio, on Murdock.

Q. Huh-uh.

A. W e got out down there about, I guess about

12 o’clock, which they have a house in the back that

is open all the time. They play records, and——

Q. Yes.

A. So Smitty and this other guy left, and I don’t

know, it was about something to three when he come

back to pick us up. When he come back he was by

his-self, so we got in the car, and we were supposed

to be going to Oklahoma when we left Wichita, and

when we got out on Kellogg on Bluff, that is when

we got stopped.

Q. I see. All right, you have been in court and

heard the testimony of the police officers who ap-

peard?

A. Yes.

Q. And were you stopped substantially as they

have testified tod

A. Yes.

Q. Then you’re stating that between the hours of

2 and 3 o’clock, or after 3 o’clock you were on Mur

dock Street?

A. No, between 12. W e got out down there about

12 o’clock.

Q. All right.

A. Until he come back, picked us up it was some

thing to 3:00.

Q. But you were in the vicinity of Murdock and

Wabash?

V

A. Ohio, the place is between Ohio and Wabash.

Q. Yes, I know where it is.

A. Yes.

Mr. Foeht: Your Honor, I object to that reality

and move that all be stricken. That is alibi with no

notice of alibi having been given, and under the case

o f State v. Rider alibi testimony from a defendant it

must be given. The state has to be given at least ten

day’s notice.

Mr. Hayes: May it please the Court, it’s also the

law of Kansasi that evidence which is subject to be

objected to must be objected to at the time that evi

dence is given, and that a motion to strike testimony

that has been given to which there has been no objec

tion comes too late, and------

Mr. Foeht: You cannot know it’s going to be alibi

until you hear it.

Mr. Hayes: Actually, there should be no objection

to the jury knowing what the facts are. I can’t see

what the state would object to.

Mr. Foeht: Your Honor, the purpose o f the alibi

statute is to give the State of Kansas a chance to

check it. I f a person intends to offer evidence that

they were at some other place at some other time,

then they must follow the statutes. In the case of

State v. Gene Austin Rider in the Supreme Court

this court held that that included the defendant, and

if he is going to offer testimony he was some place

else at another time, he must serve notice on the state

so that the alibi can be checked, and that has not

been done. I ask the testimony all be stricken and

the jury asked to disregard it.

vi

Mr. Hayes: May it please the Court, it is also the

law in the Supreme Court, Bradey v. Maryland [sic],

that the purpose of a trial is to find out what happened

and that procedural technicalities are to be waived

in lieu of constitutional rights, and, therefore, if

there is a conflict between procedural rights and the

basic constitutional rights, his constitutional rights

take precedence, and that procedure technicalities

should not be adhered to to the deprivation of a per

son whose life is in jeopardy.

The Court: Ladies and Gentlemen of the Jury,

you are advised that the testimony of Yirgil Jenkins

is stricken from the record and you are advised to

disregard it.

Is there anything further, Mr. Hayes? Ho you have

any further questions, Mr. Hayes?

Mr. Hayes: I ’m just------ by virtue of the court’s

statement I ’m just thinking.

The Court: I ’m going to excuse the jury.