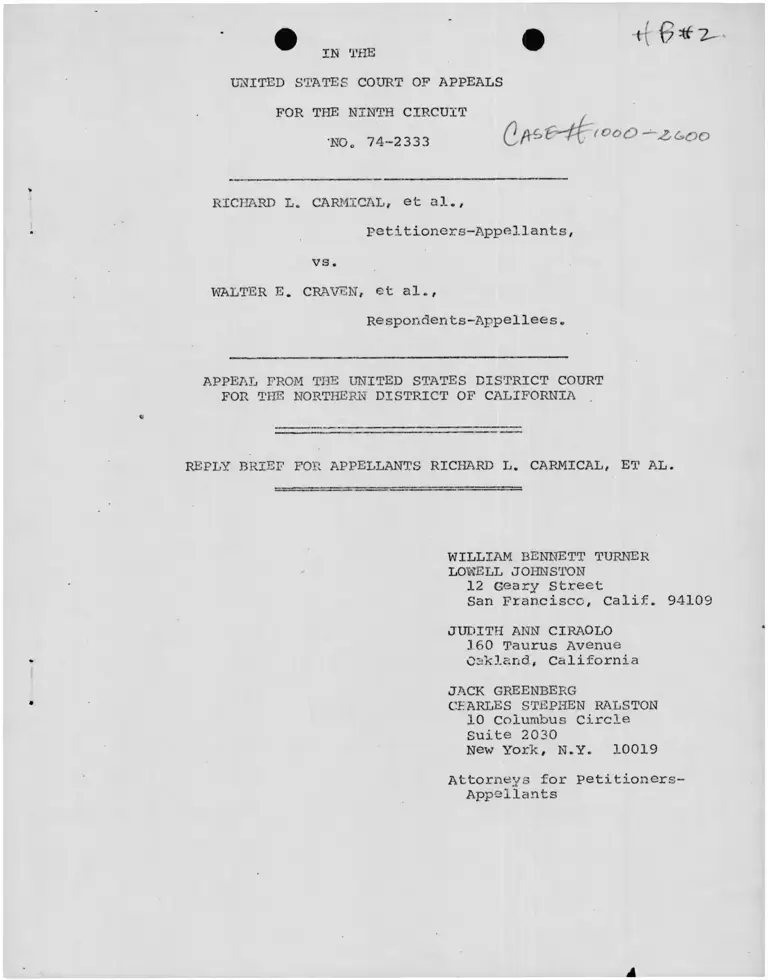

Carmical v. Craven Reply Brief for Appellants Richard L. Carmical, et al.

Public Court Documents

November 18, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carmical v. Craven Reply Brief for Appellants Richard L. Carmical, et al., 1974. 05b429d0-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/04bd18ce-2c2b-4c67-8f60-53405cb04175/carmical-v-craven-reply-brief-for-appellants-richard-l-carmical-et-al. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

t ( 9 2 -

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

•N0o 74-2333 ( O o O 6,00

RICHARD L. CARMICAL, et al. ,

petitioners-Appellants,

vs.

WALTER E. CRAVEN, et al.,

Respondents-Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS RICHARD L. CARMICAL, ET AL.

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

LOWELL JOHNSTON 12 Geary Street

San Francisco, Calif. 94109

JUDITH ANN CIRAOLO 360 Taurus Avenue

Oakland, California

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON 10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, N.Y. 10019

Attorneys for petitioners- Appellants

Index

Page

ARGUMENT

1.........................................................1

II.

A. "Retroactive" application of Carmical 1........... 4

B. There is No Basis For A Finding of Waiver

Here. . , . ...................... . ............ 8

Table of Cases

Bridgeport Guardians v. Members of Bridgeport Civil

Service Comm., 354 F. Supp. 778 (D. Conn. 1973), aff1d,

482 F.2d 1333 (2nd Cir. 1973) ..............................

Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene county, 396 U.S.

320 (1970) ................ . . . . . . . . . . . . ........ 2

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167 (2nd

Cir. 1972).............................. . .~.............. 1

Destefano v. Woods, 392 U.S. 631 (1968)...................... 6

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968) .................... 6

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963) ............................ 9

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954) ....................... 6

Hairston v. Cox. 459 F.2d 1382 (4th Cir. 1972) .............. 6

Humphrey v. Cady, 405 U.S. 504 (1972)........................ 8

Johnson v. zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938) ........ .. 9

Labat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d 698 (5th Cir. 1966) .............. 9

McNeil v. North Carolina, 368 F.2d 313 (4th Cir. 1966) . . . . 9

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935).......... ..............5

Scott v. Walker, 358 F.2d 561 (5th Cir. 1966)................ 4

- i -

Page

Smith v. Yeager, 465 F.2d 272 (3rd Cir. 1 9 7 2 ) ............... 6

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880)........... 5

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 ( 1 9 6 5 ) .................... 5

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 ( 1 9 7 0 ) .................... 2

United States v. Scott, 425 F.2d 55 (9th Cir. 1970) . . . . 8

United States ex rel. seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 53

(5th Cir. 1962)............................................. 6

Vaccaro v. United States, 461 F.2d 626 (5th Cir. 1972) . . . 8

Vulcan Society v. Civil Service Comm., 360 F. Supp.

1265 (S.D. N.Y. 1973)...................................... 2

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968).............. 8

li

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-2333

RICHARD L. CARMICAL, et al.,

petitioners-Appellants,

vs.

WALTER E. CRAVEN, et al.,

Respondents-Appellees.

Appeal From the united States District. Court

For The Northern District of California

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS RICHARD L. CARMICAL, ET AL.

I.

The arguments urged, by Respondent-Appellee are in error in

a number of respects. First, petitioners do not rely primarily

on employment cases arising under Title VII of the civil Rights

Act of 1964. To the contrary, we cited and rely primarily on

employment discrimination cases against state and local officials

arising directly under the 14th Amendment.^ The jury discrimination

Bridgeport Guardians v. Members of Bridgeport Civil Service

Commission, 354 F. Supp. 778 (D. Conn. 1973), aff'd, 482 F.2d 1333

(2nd Cir. 1973); Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167 (2nd.

• •

claim here, of course, also arises under the Fourteenth Amendment

and respondent advances no argument whatsoever as to why the same

standards should not apply. Moreover, as petitioners point out

in their main brief at page 15, one of the reasons why the courts

have read broadly the provisions of Title VII is that it expresses

Congressional policy to root out employment discrimination. The

Congressional policy (now embodied in 18 U.S.C. §243) against

discrimination in jury selection is of even longer standing,

dating from 1875. It was this fact that Justice white, relied

upon in his concurring opinion in peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493,

505 (1972), granting whites standing to challenge the exclusion

of* blacks from juries.

Second, respondent urges that the Supreme court's decision in

f a r h e r v . .Tu t v C o m m i s s i o n . 398 TT.S. 320 f l Q7D) and T u r n e r v .

Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970) are directly in conflict with the

position of petitioners in this case (Brief of Respondent, p. 76.).

This is simply not the case; rather, those decisions directly sup

port petitioners' central contention that the burden is on the

state to explain and justify a differential rate of exclusion of

blacks, whatever the standard for selection is. Turner explicitly

held that where a standard of intelligence, resulted in a much

greater rate of exclusion of blacks the jury commissioners

1/ (Cont'd)

Cir. 1972); Vulcan Society v. Civil service Commission, 360 F. Supp.

1265 (S.D. N.Y. 1973).

2

responsible for administering such a standard must justify the

result. 396 U.S. at 361. petitioners here, of course, do not

argue that the carter and Turner holdings that the states could

require that jurors be intelligent should be overruled, but only

that the mandate of those decisions be applied here.

Third, Respondent, in his attempt to justify the test, con

tinues in his fundamental misunderstanding of what is at issue.

Petitioners do not argue that those persons chosen for jury

service by the test were not competent and proper jurors. Indeed,

they argue that all registered voters must be presumed to be com

petent to serve as jurors. we again point out that Alameda County

(since 1968), all other counties in California, and the federal

C U U i . Ld C v w I iC jl C _l_ J. i. C-AlC tail U J . y H Q V C l U l i L . C x U U X A i t j |r/ w j . J . C c o X iy

well with jury lists drawn from registered, voters without resorting

to the use of tests such as the one at issue here.

The point is not that the test included competent jurors, but

that it excluded persons who were also competent. This is ex

plicitly acknowledged, by the diagram drawn by Respondent's expert,

Dr. Rusmore, reproduced in Respondent's brief on page 40, n. 33.

That diagram shows that the high cutting score that was used ex

cluded. from the pool of jurors a large number of persons who in

fact were competent to serve on juries, i.e.„ everyone above the

horizontal line and to the left of the right-hand vertical broken

line. it is this exclusion that is at issue here. petitioners'

claim is simple; the clear thinking test excluded large numbers of

persons competent to be jurors and the persons so excluded were

disproportionately blacks and low income. The result was that the

3

ua

jury lists did not reflect a cross-section of persons competent

to serve on juries. Thus, it was not enough for respondent to

introduce evidence that the test selected competent jurors. It

had to be shown that either the test did not also exclude competent

persons or there was a compelling need to use this particular

device for selection. That is, the respondent's burden was to

demonstrate that there was no other means by which jurors could

be chosen. This they did not and could not do.

Finally, with regard to the respondent's attack on the suf

ficiency of petitioners' showing below, we again reiterate that

the evidence points to the conclusion that blacks were under

represented. Therefore, the burden was on the state, as the

n a r f v r P . s n n n s ih l f i f o r a rim i n i » f e r i nrr t h e s y s t e m . f.O sh o w t h a t

in fact blacks were properly represented. See Scott v. walker, 358

2/F.2d 561 (5th Cir. 1966).

II.

A. "Retroactive" application of Carmical I.

Respondent's argument that this Court's prior decision in

Carmical I should not be given "retroactive" application here

must be rejected for three reasons.

•2/ we would point out to the court that petitioners requested the district court, if it felt that the evidence was not conclusive,

to provide for the supplementation of the record by the parties

working together towards determining, as precisely as possible, the racial composition of the jury lists. Such a procedure was

adopted by the district court in Chance v. Board of Examiners, 330

F. Supp. 203, 209 (SUD„N.Y. 1971) and resulted in detailed and

reliable figures being obtained. If this Court also feels that

the record is inconclusive as to the racial impact of the test

4

1„ There is No Question Of Retroactivity In This Case.

This Court in Carmical I. did not hold for the first time that

exclusion of blacks from juries is unconstitutional or that

federal law on jury exclusion is applicable to the states through

the Fourteenth Amendment. These are ancient principles. There

is no occasion for this Court to consider the doctrine of

"retroactivity", because Carmical marks no departure from

previously prevailing law; nor does it involve the application of

a constitutional right to the state for the first time. Rather,

Carmical is only illustrative of a long and consistent line of

erases going back 93 years to Strauder v. west Virginia, 100 U.S.

303 (1880).

rnhat- r'amlnai r!i H not- announce any new constitutional rule

is amply demonstrated by this Court's opinion. Thus, although

the respondent here has urged that Carmical is in conflict with

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965), and therefore marks a

departure with prevailing law, the fact is that the same argument

was made on the earlier appeal. This Court discussed Swain, dis

tinguished it, and rejected the state's argument that Swain fore

closed. Carmical1s claims. 457 F.2d at 587. Therefore, this Court

clearly did not view its decision as a departure in the law.

Furthermore, Carmical I. was based on a lengthy discussion of

prior decisions of the Supreme Court and other Courts of Appeals

going back to, e.g„, Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935), and

2/ (Cont'd)

then it would be appropriate to remand to the district court for

further proceedings in accord with petitioners' request.

5

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954), decided long before Carmical

and petitioner here were tried.--/ The Court placed particular reli-

iance on a 1962 decision of the Fifth Circuit (which in turn re

lied on prior holdings of the Supreme Court) that held "it is

not necessary . . . to establish ill will, evil motive, or

absence of good faith." United States ex rel seals v. Wiman,

304 F.2d 53, 65 (5th Cir. 1962).^/ In other words, it was no

departure from previous law to hold that intentional or purpose

ful discrimination by jury commissioners need not be proved.

Nor, for similar reasons, is pestefano v. Woods, 392 U.S.

631 (1968), of help to the respondent, because the present case

does not present an instance where a constitutional guarantee is

applied to the states for the first time. pestefano held that

, . . . _ ^ • • t t n i/ltr f 1 r> /C O \ 1 ^

L X i C U ^ U I O I U U juXX v » ^ ^ -*■- ̂ ** ̂ •*- * ^ v ^ / / f **-------

ing for the first time that the Sixth Amendment right to a jury

trial applies to the states, should not be given retroactive

effect. Here, the long line of Supreme Court decisions reaching

back to Strauder v. West Virginia, supra, has consistently forbade

—/ The court said that "The opinions take into account the

historical prevalence of intentional discrimination against

Negroes, but the court has never implied that the absence of

that factor destroys a prima facie case." 457 F.2d at 586.

The Third Circuit has reached the same conclusion. see

Smith v. Yeaqer, 465 F.2d 272 (3d Cir. 1972). The Fourth Circuit,

in Hairston, v, Cox, 459 F.2d 1382, 1384 (4th Cir. 1972), said that

"Since Neal v. Pelaware, 103 U.S. 370, 26 L.Ed. 567 (1881),

federal courts have allowed Negroes complaining of indict

ment or conviction by juries from which members of that race were systematically excluded to rely upon circumstantial

factors tending to show discriminatory practices in order to

obtain relief, rather than to require direct proof of dis

crimination. "

6

5/the states from discriminating against blacks in jury selection.-^

2. The Attorney General Has Admitted That Carmical Is Fully

Retroactive.

The Attorney General (by the same Deputy representing

the state in this case) sought certiorari from the Supreme Court

in Carmical I. In the Attorney General's reply brief in the

Supreme Court, it was argued that the Court should exercise cer

tiorari jurisdiction because of the great potential impact of

the decision in upsetting convictions in Alameda County. In the

reply brief, the Attorney General represented to the Supreme

Court that the carmical decision "is totally retroactive" (reply % 1

brief, page 2). Having made such a flat admission to the

Supreme Court, the Attorney General cannot in good faith now

assume an entirely contrary position. If the Attorney General

is not formally estopped from urging a contrary position, at

least the admission in Carmical is strong evidence against the

state's position here. see generally, 5 Wright & Miller, Federal

Practice and Procedure, 377 (1969).

3. settled. Principles Require The Application Of Carmical To

This Case.

Even assuming Carmical did announce a new rule of constitutional

5/ The respondent's attempted reliance on peters v. Kiff, 407

U.S. 495 (1972), is also misplaced. First, it was not the judgment

of the Supreme Court that the peters rule on standing be prospect

ive — three concurring justices merely suggested that in future

cases white defendants could challenge exclusion of blacks from

juries. Second, peters in fact involves a new rule of law in the

Supreme court. Prior to peters, the right of whites to challenge

the exclusion of blacks had not been recognized. As we have explained , Carmical I. did not involve a new rule of law.

7

law, settled principles require its "retroactive" application.

Ordinarily, of course, all decisions apply retroactively; in ex

ceptional circumstances a few decisions have been held prospective

only. See generally United States v. Scott, 425 F.2d 55, 58 (9th

Cir. 1970) (en banc). The specific constitutional right involved

here has never been held prospective. Indeed, "systematic ex

clusion of blacks from juries calls for retroactive vindication."

Vaccaro v. United States, 463 F.2d 626, 629 (5th Cir. 1972). The

Supreme Court decision most closely in point is Witherspoon v.

Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968), where the Court held;•

"The jury-selection standards employed here

necessarily undermined 'the very integrity of

the . . . process' that decided the petitioner's

f a t e r o i t a t i o n o m i t t e d ! and we tia\re o o n o l n d e d

that neither the reliance of law enforcement

officials [citations omitted] nor the impact of

a retroactive holding on the administration of

justice [citation omitted] warrants a decision

against the fully retroactive application of the

holding we announce today." 391 U.S. at 523, n.22.

In short, there is no basis for holding Carmical I. to be in

applicable to the present case.

B. There is No Basis For A Finding Of Waiver Here.

As this Court said in Carmical I., a holding of deliberate

must be based on evidence that the defendant, not his attorney,

made an "affirmative act . . . evidencing his deliberate re

jection of his constitutional guaranty." 457 F.2d at 584. See

also Humphrey y, Cady, 405 U.S. 504, 517 (1972) (requiring a

knowing waiver by the defendant himself, not his attorney); McNeil

8

v. North Carolina, 368 F.2d 313 (4th Cir. 1966); Labat v. Bennett,

365 F.2d 698, 707 (5th Cir. 1966)

The short answer to the Attorney General's novel contention

that petitioner is bound by the rule of deliberate bypass unless

Carmical I. announced a "new" rule of law is that the deicision

in Carmical I. itself shows that there was no deliberate bypass

here -- regardless of whether the court announced a new standard

for jury selection. That is, this Court in Carmical I. did not

rest its holding on deliberate bypass on the proposition that a

new standard was being announced. Rather, it relied on the

doctrine of Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963), and squarely held«

that the federal standard established there must be met.

Moreover, whether a defendant has knowingly waived a

federal constitutional right is, of course, primarily a question

of fact, and the court below made no finding on the question.

Thus, at the most, if this court reverses the district court

on the merits it might then be appropriate to remand for de

cision on the issue of waiver as to petitioners Early and

Lawrence. With regard to petitioner Carmical, on the other

hand, this court has already held that there was no waiver. The

respondent sought review on certiorari from the Supreme Court

of the United States on that specific issue and certiorari was

Although the Attorney General asserts that "all parties were 'satisfied' with the jury selected," the record provides

no support whatever for this assertion. Of course, even if

petitioner himself said he was "satisfied" with the jury, that

does not meet the federal standard of deliberate bypass. See

Carmical I., supra; Humphrey v. Cady, supra; cf. Fay v. Noia,

372 U.S. 391 (1963); Johnson vP zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938).

9

denied (409 U.S. 929 (1972)), six days after the granting of

certiorari in the case that the state now relies upon, Davis v.

United States (cert. granted, 409 U.S. 841 (1972)), and on the

same day that certiorari was granted in the companion case to

Davis, Tollett v. Henderson (cert. granted, 409 U.S. 912 (1972)).

Thus, at least with regard to Carmical, the prior decision of

this Court is the law of the case and can not be changed.

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER '

WILLIAM E. HICKMAN 12 Geary StreetSan Francisco, California 94108

JUDITH ANN CIRAOLO 160 Taurus Avenue

Oakland, California

JACK GREENBERG

CHARL.ES STEPHEN RALSTON 10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for petitioners-Appellants

10

Certificate of service

I hereby certify that I have served copies of the Reply

Brief for Appellants in the above case by depositing copies of

same in the United States Mail, air-mail, postage prepaid,

addressed as follows to the attorney for respondents-appellees:

Ms. Gloria F. DeHartDeputy Attorney General

6000 State Building

San Francisco, California 94102

* Dated: November 18, 1974.

n .

Asa y }\/‘YD̂ i

Attorney for petitioners-

Appellants

11

\