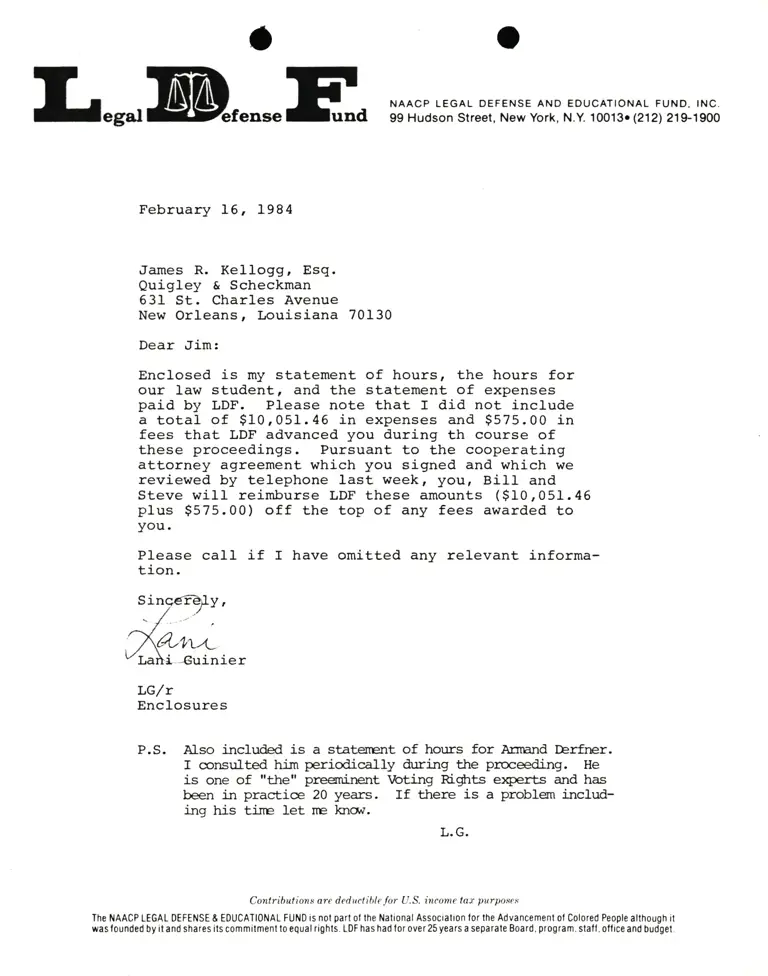

Letter from Lani Guinier to James R. Kellogg, Esg. Re: hours and expenses

Administrative

February 16, 1984

1 page

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Letter from Lani Guinier to James R. Kellogg, Esg. Re: hours and expenses, 1984. dd050569-e692-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/04e212f6-8d07-42de-8a25-89abe58b7b52/letter-from-lani-guinier-to-james-r-kellogg-esg-re-hours-and-expenses. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

Lesa,U&renseH.

February 16, 1984

James R. Kellogg, Esg.

Quigley & Scheckman

631 St. Charles Avenue

New Or1eans, Louisiana 70130

Dear Jim:

Enclosed is my statement of hours, the hours for

our law student, and the statement of expenses

paid by LDF. Please note that I did not include

a total of $10,05I.46 in expenses and $575.00 in

fees that LDF advanced you during th course of

these proceedings. Pursuant to the cooperating

attorney agreement which you signed and which we

reviewed by telephone last weekr 1rou, Bill and

Steve will reimburse LDF these amounts ($t0,051.46

plus $575.00) off the top of any fees awarded to

you.

Please call if I have omitted any relevant informa-

tion.

hA_

*;urnl_er

LG/r

Enclosures

P.S. AIso included is a staterrent of hor:rs for Arrnand Erfner.

I consulted him periodically during the proceeding. He

is one of "ttre" preen[nerrt V*ing RtSIts e>perts and has

been in practice 20 years. If ttrere is a problsn includ-

ing his tjrre let ne kncr,r.

L.G.

Contributions are deductihle lor U.S. income lar purposcs

The NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND is not part ol the National Association lor the Advancement of Colored People although it

was lounded by it and shares ils commitment to equal righls. LDF has had lor over 25 years a separate Board, program, stafl. ollice and budget.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE ANO EOUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y. 10013o (212) 21$'1900

SinrccQly,