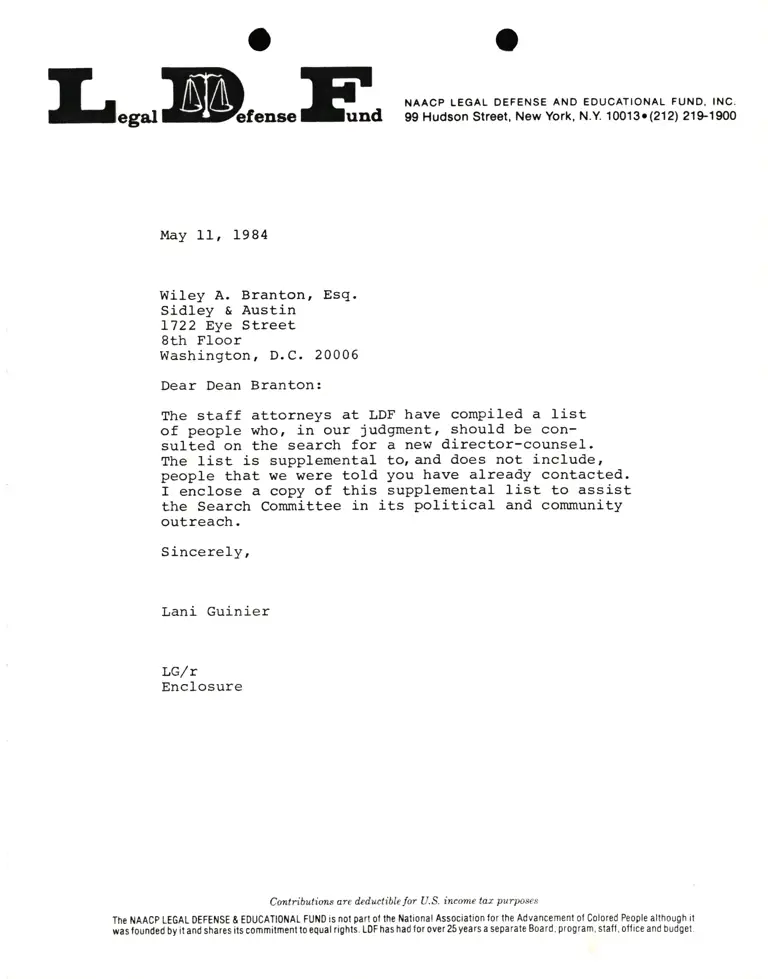

Letter from Lani Guinier to Wiley A. Branton, Esg. RE: Suggested Candidates for Director Counsel

Correspondence

May 11, 1984

1 page

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Letter from Lani Guinier to Wiley A. Branton, Esg. RE: Suggested Candidates for Director Counsel, 1984. 87aaf8f9-e592-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/050ca186-98bf-4832-b357-7ea4b49a68a9/letter-from-lani-guinier-to-wiley-a-branton-esg-re-suggested-candidates-for-director-counsel. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

Les.,U&renseHu

May 11, L984

Wiley A. Branton, Esg.

Sid1ey & Austin

L722 Eye Street

8th Floor

Washington, D.C. 20006

Dear Dean Branton:

The staff attorneys at LDF have compiled a list'

of people who, in our judgrment, should be con-

sulted on the search for a new director-counsel.

The list is supplemental to, and does not include,

people that we were told you have already contacted.

I enclose a copy of this supplemental list to assist

the Search Committee in its political and community

outreach.

Sincerely,

Lani Guinier

LG/r

Enclosure

Contributions are iledurtible lor U.S. incame tax purposes

The NAACp LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIoNAL FUND is not part ol lhe National Association lor the Advancement ol Colored People although it

was lounded by it and shares its commitment to equal rights. LDF has had lor over 25 years a separate Board, program, slafl, olrice and budget.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street, New york, N.y. 10013o(212) 21$.1900

PEOPLE WITH WHOM SEARCTI COMIT{ITTEE SHOULD

TOUCH BASE

Dennis Archer - President, NatiOnal Bar A.ssociation

Richard Arrington - Mayor, Birmingham

l,larion Barry - Pres. , National Conference of Dlayors

Harold Washington - MaYor, Chicago

Wilson C@de - llayor, PhiladelPhia

Richard Hatcher - MaYor, GarY

Coleman Young - IvIaYor, Detroit

Dutch Moria1 - MaYor, New Orleans

Willie Brown - Speaker, California State Assembly

Rep. Julian Dixon Head, Congressional Black Caucus

Reps. Gus Hawkins, Don Edwards, I,lajor Otrens, Charles Rangel

Senators Kennedy, Ivlathias

Christopher F. Edley, Sr. - United Negro College Fund

EarI Graves - Black EnterPrise

Rev. Jesse Jackson - Presidential candidate

Dorothy Height National Council Negro Women

John Jacob - Urban League

John Johnson EbonY

Lerone Bennett Historian

Tom Atkins General Counsel, NAACP; Herb Reed, P:ofessor of l-anr.r, Hovrard U.

Joseph Lowery SCLC

oemetrius Newton President, Phi Beta Sigrma

The Honorable U. W. Clemon, Gabriel McDonald, U.S. District Court

Judges

The Honorable Damon Keith, Spottswood Robinson, Court of Appeals

Judges

Arthur Fleming - former Chair, U.S. Commission on Civil Rights

Franklin Thomas President Ford Foundation

Leon Sullivan - O.I.C.

J. Clay Smith former Acting Chair, EEOC

Margaret Burnham - National Conference of Black Lawyers

Halnrood Burns N.C.B.L. and City College Legal Studies Program

Vilma l'lartinez, Joaquin Avila - I4ALDEF

President, League of Women Voters; NOW; Women's Lega1 Defense Fund

Head of the l"lasons

LDF Cooperating AttorneYs:

C.B. King (Georgia)

Avon Williams (Tennessee)

Oscar Adams, Alabama Supreme Court (forner ooSnrating attorney)

Henry l'larsh (Virginia)

John Walker (Arkansas)

Joe Hudson (I,Iississippi )

Gene Thibodeaux (Louisiana)

Fred Gray (Alabama)

Fred Banks (Mississippi)

Percy Julian (Wisconsin)

Mark McDonald (Texas)