Bush v Al Vera Brief for the United States

Public Court Documents

August 1, 1995

54 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bush v Al Vera Brief for the United States, 1995. fa5f1531-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/055fe22b-7fc2-4927-8073-d6daef64c414/bush-v-al-vera-brief-for-the-united-states. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

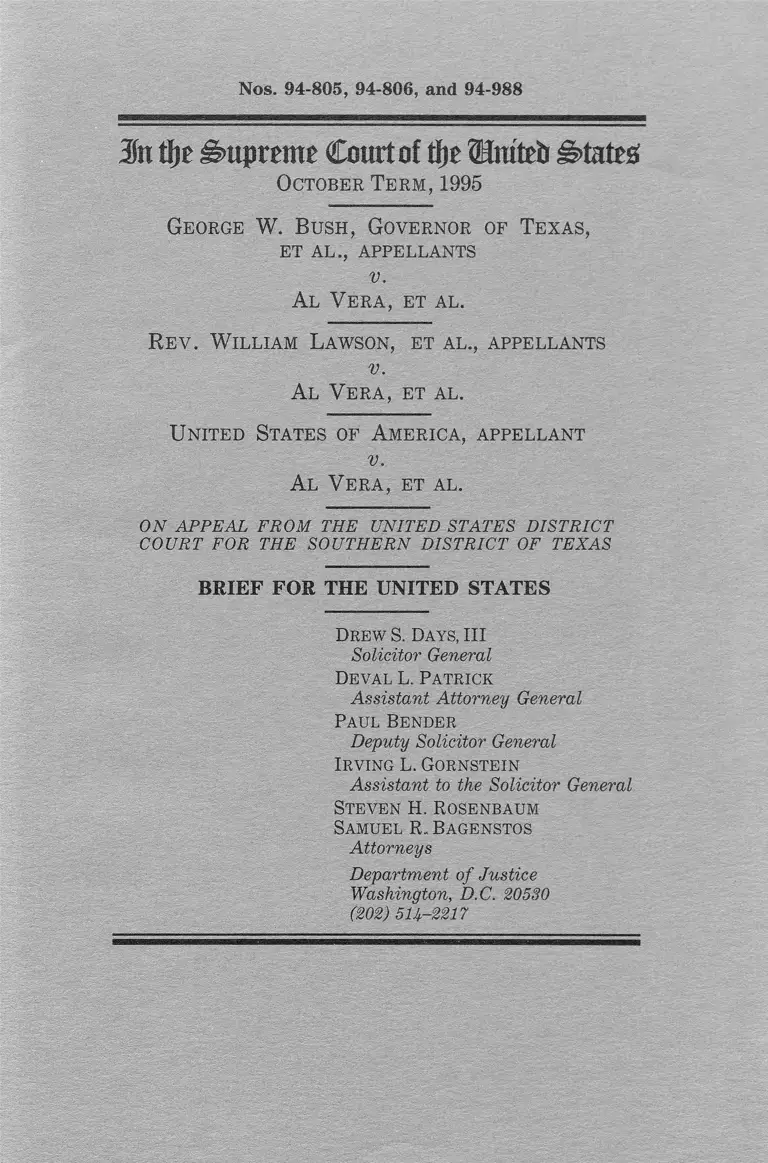

Nos. 94-805, 94-806, and 94-988

Sn tfj? Supreme Court of tf)t Ifiuteb £s>tatrs

October Term , 1995

George W. Bush, Governor of Texas,

ET AL., APPELLANTS

V.

Al Vera , et al.

Re v . William Lawson, et al., appellants

v.

Al Vera , et al.

U nited States of America, appellant

v.

Al Vera , et al.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

Drew S. Days, III

Solicitor General

Deval L. Patrick

Assistant Attorney General

Paul Bender

Deputy Solicitor General

Irving L. Gornstein

Assistant to the Solicitor General

Steven H. Rosenbaum

Samuel R. Bagenstos

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 514-2217

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether Districts 18, 29, and 30 in Texas’s congres

sional redistricting plan are narrowly tailored to further a

compelling in terest.

(I)

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING

Plaintiffs are A1 Vera, Edward Blum, Edward Chen,

Pauline Orcutt, Barabara L. Thomas, and Kenneth

Powers.

Defendants are George W. Bush, Governor of the State

of Texas; Bob Bullock, Lieutenant Governor; Pete Laney,

Speaker of the House of Representatives; Dan Morales,

Attorney General; and Antonio Garza, Jr., Secretary of

State.

Defendant-Intervenors are Rev. William Lawson, Zollie

Scales, Jr., Rev. Jew Don Boney, Deloyd T. Parker, Dewan

Perry, Rev. Caesar Clark, David Jones, Fred Hofheinz,

Judy Zimmerman, Robert Reyes, Angia Garcia, Robert

Anguiano, Sr., Dalia Robles, Nicolas Dominguez, Oscar T.

Garcia, Ramiro Gamboa, League of United Latin Ameri

can Citizens, and the United States.

II

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinion below.......................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ................................................ 2

Constitutional and statutory provisions involved ................ 2

Statement ............................................ 2

Summary of argument .......................................................... 14

Argument:

Introduction ................... 17

The State’s redistricting plan satisfies strict scrutiny .... 18

A. The State had a compelling interest in drawing one

black opportunity district in Dallas County and one

black and one Hispanic opportunity district in

Harris County in order to comply with Section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act ..................................... 19

B. The State also had a compelling interest in drawing

one black opportunity district in Dallas County and

one black and one Hispanic opportunity district in

Harris County in order to counteract the effects of

racially polarized voting ........ 32

C. Districts 18, 29, and 30 are narrowly tailored to

achieve the State’s compelling interests.................. 35

Conclusion ..................................... 46

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena, 115 S. Ct. 2097

(1995) .................................................................... 18, 21, 33, 35

Beare v. Smith, 321 F. Supp. 1100 (S.D. Tex. 1971),

aff’d sub nom. Beare v. Briscoe, 498 F.2d 244 (5th

Cir. 1974) ......... 33

Bob Jones Univ. v. United States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983) . 21

Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73 (1966) ............... 40, 41, 43

Chapman v. Meier, 420 U.S. 1 (1975) ............................. 40

Page

( H I )

IV

City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469

(1989) ............................................................... 21, 23, 33, 34, 35

City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156 (1980) ..... 21, 22

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973) ................... 41

Garza v. County of Los Angeles, 918 F.2d 763 (9th Cir.

1990), cert, denied, 498 U.S. 1028 (1991)....................... 45

Growe v. Emison, 113 S. Ct. 1075 (1993).............. 22, 24, 25, 40

Hays v. Louisiana, 839 F. Supp. 1188 (W.D. La. 1993),

vacated and remanded, 114 S. Ct. 2731 (1994) ............. 36

Jeffers v. Clinton, 756 F. Supp. 1195 (E.D. Ark. 1990),

aff’d mem., 498 U.S. 1019 (1991) ....... ........................... 37

Johnson v. DeGrandy, 114 S. Ct. 2647 (1994).......... 15, 24, 25

Johnson v. Transportation Agency, 480 U.S. 616

(1987) ............................................................................... 23

Jones v. City of Lubbock, 727 F.2d 364 (5th Cir. 1984) . 22

Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725 (1983)....................... 41

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) ................. 21

Ketchum v. Byrne, 740 F.2d 1398 (7th Cir. 1984), cert.

denied, 471 U.S. 1135 (1985) .................................... ...... 37, 45

Lipscomb v. Wise, 399 F. Supp. 782 (N.D. Tex. 1975),

rev’d, 551 F.2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1977), rev’d, 437 U.S.

535 (1978) ........... 27

Local 28 ofFSheet Metal Workers’ Int’l Ass’n v. EEOC,

478 U.S. 421 (1986) .......................................................... 21

Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. La. 1983) ....... 21

McGhee v. Granville County, 860 F.2d 110 (4th Cir.

1988) ................................................................................ 31

Miller v. Johnson, 115 S. Ct. 2475 (1995) ..... 17, 19, 22, 23,

36, 39, 40, 42, 45

Nipper v. Smith, 39 F.3d 1494 (11th Cir. 1994), cert.

denied, 115 S. Ct. 1795 (1995) ......................................... 34

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U.S. 73 (1932) .................. .......... 3, 33

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U.S. 536 (1927) ......................... 3, 33

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970) ......................... 21

Personnel Administrator v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256

(1979) ............................................................................... 45

Cases—Continued: Page

V

Rybicki v. State Bd. of Elections, 574 F. Supp. 1082

(N.D. 111. 1982) ................................................................ 45

Seaman v. Upham:

536 F. Supp. 931 (E.D. Tex.), vacated and remanded,

456 U.S. 37 (1982) .................................................. 9

No. P-81-49-CA (E.D. Tex. Jan. 30, 1984) ................. 28

Shaw v. Hunt, 861 F. Supp. 408 (E.D.N.C. 1994),

probable juris, noted, 115 S. Ct. 2639 (1995) ............. 31, 36, 39

Shaw v. Reno, 113 S. Ct. 2816 (1993)...................... 22, 35, 36

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944) ........................ 3, 33

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966) .. 19, 21, 22

Terrazas v. Slagle:

789 F. Supp. 828 (W.D. Tex. 1991), aff’d, 112 S. Ct.

3019, 113 S. Ct. 29 (1992) ........................................ 12

821 F. Supp. 1162 (W.D. Tex. 1993)........................... 12

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953)............................ 3, 33

Texas v. United States, 384 U.S. 155 (1966)................. 3, 33

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) . 13, 15, 22, 24, 25, 31

United Jewish Organizations of Wi l Hams burgh, Inc. v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977) .................. .......................... 34

United, States v. Marengo County Comm’n, 731 F.2d

1546 (11th Cir. 1984)........................................................ 22

United States v. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149 (1987)..... 18, 21, 35

Upham v. Seamon, 456 U.S. 37 (1982) .......................... 31, 40

Voinovich v. Quilter, 113 S. Ct. 1149 (1993) .................. 25, 40

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973).................... 3, 27, 33

White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783 (1973) ............................. 40

Williams v. City of Dallas, 734 F. Supp. 1317 (N.D.

Tex. 1990) ....................................................................... 7, 27

Wygant v. Jackson Bd. of Educ., 476 U.S. 267

(1986) ............................................................................... 23, 42

Constitution and statutes:

U.S. Const.:

Amend. XIV .................. ............................ 2, 14, 21, 22, 33

§ 1 (Equal Protection Clause) ............................ 2, 42, 44

§ 5 ................................... ......................................... 21

Cases—Continued: Page

VI

Constitution and statutes—Continued: Page

Amend. X V ........................................................... 14, 21, 22

§ 2 ............................................................................. 21

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. 1973 et seq.:

§ 2, 42 U.S.C. 1973 .................................................. passim

§ 2(a), 42 U.S.C. 1973(a) ........................................... 20

§ 2(b), 42 U.S.C. 1973(b) ........................................... 20, 31

§ 5, 42 U.S.C. 1973c ..................................... 2, 3, 11, 19, 20

Miscellaneous:

S. Rep. No. 295, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975) ................... 3

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982) .............. 20, 21, 45

M tjjt Supreme Court of tf)t :§>tatr£

October Term , 1995

No. 94-805

George W. Bush, Governor of Texas,

ET AL., APPELLANTS

V.

Al Vera , et al.

No. 94-806

Rev . William Lawson, et al ., appellants

v.

Al Vera , et al.

No. 94-988

U nited States of America, appellant

v.

Al Vera , et al.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the three-judge district court (J.S. App.

la-104a) is reported at 861 F. Supp. 1304.

(1)

2

JURISDICTION

An order of the three-judge district court was entered

on September 2,1994. J.S. App. 105a-106a. That order was

amended to afford injunctive relief on September 20, 1994.

Id. at 107a-108a. A notice of appeal was filed on October 3,

1994. Id. at 109a-110a. This Court noted probable ju ris

diction on June 29, 1995. 115 S. Ct. 2639 (1995). The ju ris

diction of this Court rests on 28 U.S.C. 1253.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment provides that “[n]o State shall * * * deny to any

person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the

laws.” The relevant statutory provisions are Sections 2

and 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, 42

U.S.C. 1973, 1973c, which are reproduced in the Appendix

to the Jurisdictional Statement. J.S. App. llla-113a.

STATEMENT

This case involves a challenge to the State of Texas’s

1991 congressional redistricting plan. A three-judge dis

trict court invalidated three districts in the plan that were

drawn to afford black and Hispanic voters an opportunity

to elect candidates of their choice. The court found that

those three districts—one in Dallas County and two

in Harris County—placed voters into different d istric ts

on the basis of race without sufficient justification in

violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment. The United States, a defendant-

intervenor below, has appealed from that judgment. The

State of Texas and private intervening defendants have

also appealed.

1. a. The State of Texas has a long history of discrimi

nation against racial minorities in voting and in the law

3

governing elections. See J.A. 359-367; St. Exh. 17; see also

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) (racially dilutive

multimember districts); Texas v. United States, 384 U.S.

155 (1966) (per curiam) (poll tax); Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S.

461 (1953) (white primary); Sm ith v. Allwright, 321 U.S.

649 (1944) (same); N ixon v. Condon, 286 U.S. 73 (1932)

(same); N ixon v. Herndon, 273 U.S. 536 (1927) (same).

That well-documented history of discrimination prompted

Congress to extend Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act to

Texas in 1975. See S. Rep. No. 295, 94th Cong., 1st Sess.

25-30 (1975). No district in Texas with a majority of white

residents has ever elected a black member to Congress.

St. Exh. 17, at 55. Nor has any black state senator ever

been elected from a majority-white district. Id. at 51-52.

Only two black state house members have been elected

from districts with white population majorities. Id. at 51.

Similar data exists regarding the failure of Hispanic

candidates to win elections in districts with white

majorities. J.A. 252; U.S. Exh. 1095 (letter dated Nov. 12,

1995, at 2).

b. Between 1980 and 1990, the population of Texas grew

from approximately 14.2 million to almost 17 million. J.S.

App. 9a. As a result, Texas was allocated three additional

congressional seats in 1991, giving it a total of 30 seats.

Ibid. The growth of the Hispanic and black populations in

Texas during the 1980s was particularly substantial. Id.

at 9a-10a. During that decade, the Hispanic population

increased by more than 45%, and the black population

increased by nearly 17%, while the Anglo population

increased by 10%. Id. at 10a. By 1990, Hispanics consti

tuted 22.5% of the total population, blacks constituted

11.6% of the population, and the percentage of Anglos had

declined to-60.5% of the State’s total population. Id. at 9a.

Much of Texas’s population growth during the 1980s

occurred in Harris County (in which Houston is located),

4

Dallas County (in which Dallas is located), and Bexar

County (in which San Antonio is located). J.S. App. 10a.

Increased Hispanic and black population accounted for

most of the growth in those counties. Id. at 10a-12a. In

recognition of the growth of population in Harris, Dallas

and Bexar Counties, the Texas legislature placed Texas’s

three new congressional districts in those counties and

drew the new districts in a way that would afford His-

panics and blacks in those areas the opportunity to elect

candidates of their choice despite the State’s history

of racial discrimination in voting. Id. at 19a. Considered

statewide, the plan enacted by the State in 1991 gave

Hispanics an opportunity to elect candidates of their

choice in seven of the State’s 30 districts and blacks an

opportunity to elect candidates of their choice in two

districts. See PL Exh. 36, at 27.

c. In addition to affording the black and Hispanic

minorities opportunities to overcome Texas’s history

of racial discrimination in voting, the State’s 1991 plan

also reflected the legislature’s commitment to two other

principles—that congressional districts would all contain

the same number of residents and that district lines

would be drawn to protect the reelection prospects of

all incumbent representatives. J.A. 246-249; 1 Tr. 85; 3

Tr. 163, 215; U.S. Exh. 1071 Supp. at 12. The State has

traditionally viewed incumbency protection as a very

important consideration in redistricting. J.S. App. 12a-

13a. Following the 1960 Census, for example, the State

gained a congressional seat, but redistricted by creating

an at-large seat in order to allow all incumbents’ d istricts

to remain intact. Id. at 12a. Later in the 1960s, Texas

created a district that traversed a large portion of the

State in order to protect an incumbent. Id. at 12a-13a.

During redistricting in the 1970s, a delegation of state

legislators working on redistricting flew to Washington,

5

D.C., to meet with members of the Texas congressional

delegation on a group and individual basis. Id. at 13a. A

participant in the redistricting process in the 1980s and

1990s testified that, “[f]or the most part, the only

traditional districting principles that have ever operated

here are that incumbents are protected and each party

grabs as much as it can.” Id. at 13a n.9.

In the 1991 redistricting, the state legislature agreed to

protect the seat of every sitting representative. J.S. App.

26a. Each Member of Congress and each state legislator

with an interest in a particular district had an opportunity

to help draw the lines of the district during the mapping

process. Id. at 25a-26a. Representatives and legislators

drew on several sources to assist them in that process.

The legislature’s computers could provide past election

results on the redistricting maps on a precinct-by

precinct level; racial information about population was

available at the census block level. Id. at 27a. Repre

sentatives also knew the partisan makeup of various areas

from their own election experience and from driving

through those areas. 3 Tr. 177-179. In addition. Demo

cratic representatives and legislators had access to a

database that provided political information on a

household-by-household basis; they could therefore obtain

the number of Democratic primary voters residing in any

proposed district. Id. at 179. Incumbent congressional

representatives and state legislators contemplating a run

for Congress would often go to a legislative mapping room

to evaluate proposed districts and to suggest changes that

would improve their chances of winning. Id. at 168.

2. This appeal involves districts drawn in Dallas and

Harris Counties. In deciding how to draw the districts in

those two counties, the legislature took into account its

obligations under the Voting Rights Act. J.S. App. 18a-

22a. Believing that the Voting Rights Act required it to

6

do so, the legislature created a new black opportunity

district in Dallas County and a new Hispanic opportunity

district in Harris County. Id. at IS a^ la .1 In addition, the

legislature reconfigured a district in Harris County in

which blacks had been able to elect a candidate of their

choice over the past two decades so that they would con

tinue to have that opportunity. Id. at 19a-21a.

The population of Dallas County is sufficient to support

three and one-third districts. U.S. Exh. 1085. Blacks

make up approximately 20% of the population in the

County. U.S. Exh. 1084. In the State’s plan, Dallas

County is divided among seven districts. Four of those

districts draw most of their population from Dallas

County. PL Exh. 34P. The State’s plan affords blacks in

Dallas County an opportunity to elect a candidate of their

choice in one of those four districts. PI. Exh. 4C.

The Harris County population is sufficient to support

five congressional districts. U.S. Exh. 1085. Hispanics

make up approximately 23% of the population of the

County, and blacks make up approximately 19% of the

population. U.S. Exh. 1084. In the State’s plan, H arris

County is divided among seven congressional districts.

Three of those districts draw all of their population from

Harris County and one draws most of its population from

it. PI. Exh. 34P. The State’s plan contains one district

in Harris County that provides blacks with an opportunity

to elect a candidate of their choice and one district that

provides Hispanics with such an opportunity. J.A. 185,229.

1 An opportunity district is a district in which the relevant mi

nority group has a meaningful opportunity to elect the representative

of its choice despite racial discrimination in voting either because it

constitutes a voting majority in the district or because it constitutes a

sizable minority that can elect its preferred candidate because some

non-minorities will vote for the minority-preferred candidate.

7

a. District 30 is the black opportunity district in

Dallas County. That district has a core area that contains

half of the district’s population and that is 69% black. J.S.

App. 29a; J.A. 335. The district contains seven additional

areas, each of which is highly irregular in shape. Ibid.

The population of each of those areas is between 20% and

38% black. Ibid. Overall, District 30 is 50% black in total

population, 47.1% black in voting-age population (VAP),

and 50.3% black in citizen voting-age population (CVAP).

St. Exh. 14; J.S. App. 30a. The black community in Dallas

County believed a 50% black population district to be nec

essary to ensure that it would have an opportunity to elect

a candidate of its choice. Id. at 22a.

The legislature decided to draw a black opportunity dis

trict in Dallas County in order to comply with the Voting

Rights Act. J.S. App. 18a-20a, 89a-90a. The legislature

knew that it was possible to create a reasonably compact

black opportunity district in Dallas County. At least two

such plans were presented to it, J.A. 139 (Johnson plan);

PI. Exh. 33 (Owens-Pate plan); see J.S. App. 59a-60a, 78a,

88a. The legislature was also aware that blacks in Dallas

County are politically cohesive and that whites in the

County usually vote as a bloc against black-preferred

candidates. Shortly before the 1991 redistricting process

began, a federal district court had found that voting in

Dallas was racially polarized. W illiams v. City of Dallas,

734 F. Supp. 1317 (N.D. Tex. 1990). Legislators involved in

the redistricting process were aware of that finding. See

Lawson Exhs. 7, 11.

Although it was possible to draw a reasonably compact

black opportunity district in Dallas County, political

considerations prevented that result. In practice, the

lines of District 30 were the product of compromise among

three incumbent elected officials: Eddie Bernice Johnson,

Martin Frost, and John Bryant. J.S. App. 35a-38a. John-

son, who is black, is now the congressional representative

from District 30. Id. at 30a. In 1991, Johnson was a

Democratic state senator from Dallas County and the

chair of the State senate’s committee on congressional

redistricting. Id. at 30a-33a. Frost and Bryant were in

cumbent white Members of Congress from Dallas. Id. at

33a. Prior to the 1991 redistricting, F rost’s and B ryant’s

districts had divided heavily Democratic south Dallas

County between them. PL Exh. 28C; 3 Tr. 187.

Early in the redistricting process, Johnson suggested a

plan that included a reasonably compact district in Dallas

with a 44% black total population. J.A. 139. That d istrict

would have afforded black voters an opportunity to elect

the candidate of their choice. J.A. 234 & n.21; 5 Tr. 21.

Johnson’s proposed district was rejected, however, because

it included substantial portions of F rost’s and Bryant’s

existing districts, as well as Frost’s and Bryant’s own

residences, in the new District 30. J.S. App. 35a & n.22,

59a. Another plan submitted to the redistricting com

mittee, the “Owens-Pate plan,” also drew a reasonably

compact black opportunity district in Dallas. PL Exh. 33;

J.S. App. 59a, 88a. That plan required eight incumbents to

run against each other in four districts, however, and did

not have the votes to pass. 4 Tr. 84, 179.

The ultimate shape of District 30 was dictated by a

compromise designed to create a black opportunity d istrict

in which Johnson could run for Congress while still per

mitting Bryant and Frost to maintain a favorable partisan

political mix in their districts. 1 Tr. 56-81, 3 Tr. 185-207.

Bryant and Frost both objected to losing black and white

Democratic voters in the southern area of proposed Dis

trict 30. J.S. App. 36a. Frost especially objected to losing

Democrats from the racially mixed Grand Prairie area

who had supported him in past elections. Id. at 36a &

n.23; 3 Tr. 188-189. Frost and Bryant had an interest in

9

retaining black voters because those voters had voted

overwhelmingly Democratic in the past. J.S. App. 37a-38a.

In order to satisfy those concerns of Frost and Bryant,

several concentrations of black voters were removed from

District 30 as it was originally proposed by Johnson and

retained in F rost’s and Bryant’s Districts. 1 Tr. 80.

District 30 was thus required to extend into north Dallas

County in order to contain sufficient total population and

sufficient black population to enable it to be a black op

portunity district. J.A. 149; 3 Tr. 187-189. That led the

State to create the irregular extensions that characterize

the borders of District 30.

b. District 18 is the black opportunity district in

Harris County; District 29 is the Hispanic opportunity

district. The lines separating Districts 18 and 29 are

highly irregular and closely track Hispanic and black

population concentrations. J.S. App. 40a-41a. District 18

is 51% black in total population, 48.6% black in VAP, and

52.1% black in CVAP. St. Exh. 14; J.S. App. 40a. D istrict

29 is 60.6% Hispanic in total population, 55.4% Hispanic in

VAP, and 42.5% Hispanic in CVAP. Ibid.

The state legislature decided to draw one Hispanic

opportunity district and one black opportunity district in

Harris County in order to comply with the Voting Rights

Act. J.S. App. 18a-19a, 89a-90a. In prior redistrictings,

blacks and Hispanics had been combined to form a majority

of the population in District 18. St. Exh. 17, at 44, 55-56.

As of the 1980 redistricting, the district’s population was

40.8% black and 31.2% Hispanic. See Seamon v. Upham,

536 F. Supp. 931, 984 (E.D. Tex.) (three-judge court),

vacated and remanded on other grounds, 456 U.S. 37 (1982)

(per curiam). Throughout the 1980s, blacks and Hispan

ics had voted together to elect black representatives to

Congress. St. Exh. 17, at 55-56.

10

By 1990, however, the coalition between blacks and

Hispanics had begun to disintegrate. J.S. App. 22a-23a.

The state legislature was aware in 1991 that black and

Hispanic voters no longer voted together consistently, as

several recent elections in Houston had demonstrated

(Lawson Exh. 26; PI. Exhs. 4C, 15H). At the outset of

the 1991 redistricting, Hispanics in Harris County made

clear that they opposed the creation of districts in which

blacks and Hispanics were combined to form a majority.

J.S. App. 23a. Hispanic leaders believed that the signif

icant increase in Hispanic population during the 1980s

justified the creation of a new Hispanic opportunity dis

trict in Harris County; they favored a plan that would

create such a district while retaining a black opportunity

district. Id. at 42a-43a. A consensus emerged in the leg

islature to support that proposal. Id. at 42a.

The minority populations in Harris County are suffi

ciently concentrated to permit the drawing of either

one reasonably compact black opportunity district or

one reasonably compact Hispanic opportunity district.

J.A. 197-198 (black); J.A. 199-200 (Hispanic). It is unclear

whether it was possible to draw both a reasonably

compact black opportunity district and a reasonably

compact Hispanic opportunity district simultaneously.

The Owens-Pate plan set out to accomplish that result.

Questions were raised, however, about the compactness of

the black opportunity district that Owens-Pate provided.

2 Tr. 132. And the Hispanic opportunity district provided

by that plan afforded significantly smaller opportunity for

Hispanics to elect the representative of their choice than

did the plan ultimately enacted by the state legislature.

4 Tr. 205. Nonetheless, the Owens-Pate plan would have

provided blacks an opportunity to elect a representative

of their choice in one district; it would have provided

Hispanics with at least some opportunity to elect a

11

representative of their choice in another district; and the

districts in that plan were much more compact than

the districts ultimately enacted by the legislature. See

PL Exh. 32a; J.S. App. 88a. As noted above, however, the

Owens-Pate plan, which required incumbents to run

against each other, was rejected.

As was the case with District 30 in Dallas County,

political considerations significantly affected the ultimate

shape of Districts 18 and 29. A logical way to reconfigure

District 18 would have been to model it upon the majority -

black state senate district in Harris County. J.S. App. 44a

& n.29. A proposal to do that, however, was blocked by

Mike Andrews, an incumbent Member of Congress from a

majority-white district in Harris County, who would have

lost a large part of his congressional district under that

proposal. Id. at 44a. In addition, Craig Washington, then

the incumbent Member of Congress for District 18, in

sisted that new District 18 move out of the Sunnyvale

area of southern Harris County and into northern H arris

County in order to avoid including an opposition candidate

in his district. 4 Tr. 45-46.

Negotiations between Roman Martinez and Gene Green,

state legislators who aspired to run for Congress in the

new District 29, also influenced the shape of the two

districts. J.S. App. 42a & n.27. Green wanted the new

district to include a group of non-Hispanic voters who

had voted for him as a state senator. Id. at 44a-45a. That

required the drawing of highly irregular lines in order

to capture sufficient additional Hispanic voters to retain

the Hispanic population in the district that the legislature

believed was necessary for Hispanics to have an oppor

tunity to elect a candidate of their choice. Id. at 45a.

3. The Attorney General of the United States pre

cleared the State’s 1991 redistricting plan under Section 5

of the Voting Rights Act. J.A. 343-344. The State’s plan

12

was then challenged by plaintiffs who alleged that it

violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and a

constitutional prohibition against partisan gerrym ander

ing. J.S. App. 16a-17a. In Terrazas v. Slagle, 789 F. Supp.

828 (W.D. Tex. 1991) (three-judge court), aff’d, 112 S. Ct.

3019, 113 S. Ct. 29 (1992); 821 F. Supp. 1162 (W.D. Tex.

1993) (three-judge court), a federal district court rejected

those claims.

Appellees then filed the present suit. Appellees are six

Texas voters, five of whom live in the districts at issue on

this appeal. J.S. App. 6a. They alleged that 24 of the

State’s 30 congressional districts, including the three

districts at issue here, were the product of racial g e rry

mandering and lacked sufficient justification. Id. at 4a, 6a-

7a. The district court permitted the United States, six

African-American voters, the League of United Latin

American Citizens, and seven Hispanic voters to intervene

as defendants. Id. at 7a. After a trial, the district court

concluded that Districts 18, 29, and 30 were unconsti

tutional. Id. at 4a-5a. The court upheld the 21 other

districts challenged by appellees. Id. at 5a.

The district court held that redistricting is suspect

under Shaw when it results in “bizarrely shaped d istric ts

whose boundaries were created for the purpose of racially

segregating voters.” J.S. App. 65a. Applying that test, the

court held that the districts at issue here called for s tric t

scrutiny. The court specifically found that the boundaries

of District 30 in Dallas County were convoluted and were

deliberately made that way to include a population that

was 50% black. Id. at 77a-81a. The court also found that

the lines dividing Districts 18 and 29 in Harris County

appear “utterly irrational—unless one factors in the

overlap between these district boundaries and the racial

makeup of their underlying populations.” Id. at 83a-84a.

The court concluded that “[t]he goal of separating His

13

panic and African-American residents from each other and

from the white population for the purposes of voting led to

the creation of [Districts 18 and 29].” Id. at 84a.

Applying strict scrutiny, the court found that none of

the three districts was narrowly tailored to achieve a

compelling state interest. The court stated that “[i]t is

not obvious to this court that the State justifiably feared

potential liability under § 2 or § 5 of the Voting Rights Act

if it failed to protect District 18 and set aside [D istricts

29 and 30] for minority Congressmen.” J.S. App. 89a-90a

(footnote omitted). In that regard, the court found that

Districts 18, 29, and 30 do not satisfy the Section 2

compactness requirement set forth in Thornburg v.

Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986). J.S. App. 89a n.54. Neverthe

less, the court found that, “[to comply with the Voting

Rights Act] and other reasons, the Legislature created

the districts,” and, “[according to Shaw, this is permis

sible if the districts are narrowly tailored to comply with

Voting Rights Act concerns.” Id. at 90a.

On the issue of narrow tailoring, the court held that,

“[b]eeause a Shaw claim embraces the district’s appear

ance as well as its racial construction, narrow tailoring

must take ^oth these elements into account.” J.S. App.

91a. For that reason, the court concluded that, “to be

narrowly tailored, a district must have the least possible

amount of irregularity in shape, making allowances for

traditional districting criteria.” Ibid. Because the court

found that the State could have constructed alternative

minority opportunity districts that were much more

geographically compact than Districts 18, 29, and 30, the

court concluded that those districts were not narrowly

tailored to further the State’s interest in complying with

the Voting Rights Act. Id. at 92a-93a. The court rejected

the contention that the State’s interest in protecting

incumbents was relevant to the narrow tailoring inquiry,

14

reasoning that the argument “implicitly equatfed] incum

bent protection with a compelling state interest.” Id.

at 91a. The court noted that “Shaw nowhere refers

to incumbent protection as a traditional d istricting

criterion.” Id. at 69a.

4. On September 2, 1994, the district court entered an

order permitting the 1994 elections to be held under the

existing redistricting plan, but directing the State to

prepare a new plan by March 15, 1995. J.S. App. 105a-106a.

On September 20, 1994, the court entered an order amend

ing the September 2 order so that it enjoined the use of the

redistricting plan for the 1996 elections. Id. at 107a-108a.

On December 23, 1995, this Court stayed the district

court’s orders pending disposition of the appeal.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The district court erred in holding that Districts 18, 29,

and 30 do not satisfy strict scrutiny. Those districts are

narrowly tailored to further Texas’s compelling in terests

in complying with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and

ameliorating the effects of racially polarized voting.

A. Texas had a compelling interest in drawing one

black opportunity district in Dallas County and one black

and one Hispanic opportunity district in Harris County in

order to comply with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

Section 2 is a constitutional exercise of Congress’s power

to enforce the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and

furthers the compelling interest in eliminating the effects

of racial discrimination in voting. State compliance with

Section 2 furthers that same compelling in terest.

A State has a compelling interest in creating minority

opportunity districts in order to comply with Section 2

when it has a firm basis in evidence for believing that such

districts are required by that provision. Such a firm basis

exists when (1) members of the minority group are suffi

15

ciently numerous and concentrated to have the oppor

tunity to elect candidates of their choice in a reasonably

compact district; (2) the minority group is politically

cohesive; (3) whites have engaged in significant bloc voting

against minority-preferred candidates; and (4) the failure

to create a minority opportunity district would leave mi

nority group members substantially underrepresented

when compared to their percentage in the relevant popula

tion. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 50-51 (1986);

Johnson v. DeGrandy, 114 S. Ct. 2647, 2658 (1994). Texas

had sufficient evidence to satisfy those requirements for

the three districts challenged in this case.

The district court did not address that evidence. It held

that, because the districts actually enacted in the State’s

plan do not satisfy the Gingles compactness requirem ent,

Section 2 could not provide any justification for creating

them. To have a compelling interest in complying with

Section 2, however, the State was not required to show

that the districts it actually drew satisfied the Gingles

compactness requirement. The question at the compelling

interest stage of the inquiry is whether reasonably

compact minority opportunity districts could have been

drawn. When such districts could have been drawn and

there is a strong basis in evidence for the State to believe

that the other preconditions are established, the State has

a compelling interest in drawing minority opportunity

districts in order to comply with Section 2. The question

whether the State has furthered that interest in a consti

tutionally permissible manner is a question of narrow

tailoring.

B. In addition to its interest in complying with the

Voting Rights Act, the State also had a compelling in

terest in ameliorating the consequences of racial bloc

voting attributable to past and present discrimination.

The State was faced with persistent patterns of racially

16

polarized voting. It could create minority opportunity dis

tricts in order to ensure that racially polarized voting

did not cause minority group members to be severely

underrepresented.

C. D istricts 18, 29, and 30 were narrowly tailored to

further the State’s two compelling interests. A S tate’s

plan is narrowly tailored if it uses racial considerations no

more than is reasonably necessary in order to achieve its

compelling interests. A State violates that standard if, in

creating minority opportunity districts, it (1) creates

more such districts than necesary to comply with the

Voting Rights Act or to eliminate the effects of racially

polarized voting; (2) packs substantially more minority

voters than necessary into those districts; or (3) departs

from its traditional districting criteria more than is nec

essary in order to satisfy its compelling or other legit

imate redistricting interests. The districts at issue here

did not violate any of those restrictions.

The district court held that the challenged districts are

not narrowly tailored because the State could have drawn

minority opportunity districts that were more compact. If

the State had drawn those other districts, however, it

would have had to sacrifice its strong traditional in terest

in protecting incumbents. In order to protect incumbents

while achieving its compelling interest in creating mi

nority opportunity districts, the State was required to

draw irregularly shaped districts.

The district court’s conclusion that Shaw requires a

State to draw compact districts even if that means that the

State cannot protect incumbents is incorrect and based

on a misreading of Shaw. The district court’s conclusion

conflicts with this Court’s repeated holdings that federal

courts must not substitute their own redistricting pref

erences for those of the States. It also seriously under

17

mines Congress’s goal of encouraging voluntary compli

ance with Section 2.

Because the district court applied incorrect legal

standards, its judgment should be reversed or, alterna-

tively, the decision should be vacated and the case

remanded for a decision under the correct legal standards.

ARGUMENT

In troduction

In their briefs, the State of Texas and the

Lawson/LULAC intervenors argue that the lower court

erred in its decision to apply strict scrutiny to the

congressional districts at issue on this appeal. In M iller v.

Johnson, 115 S. Ct. 2475 (1995), this Court held that s tric t

scrutiny is required if “race was the predominant factor

motivating the legislature’s decision to place a significant

number of voters within or without a particular district.

To make this showing, a plaintiff must prove that the

legislature subordinated traditional race-neutral dis

tricting principles * * * to racial considerations.” Id. at

2488. Plaintiffs will satisfy this “demanding” threshold

standard only where they can “show that the State has

relied on race in substantial disregard of customary and

traditional districting practices.” Id. at 2497 (O’Connor, J.,

concurring).

The decision below that strict scrutiny was applicable

here was made before the M iller decision and the district

court did not have the benefit of the M iller opinion in

making that judgment. The record in this case shows that

protection of incumbents is a customary and traditional

Texas redistricting practice, and the district court found

that incumbency protection played an important role in the

final shape of the challenged districts. The district court

nevertheless refused to consider as legally significant

18

whether and to what extent incumbency protection ex

plained the challenged districts (J.S. App. 66a-72a). That

refusal was inconsistent with M iller.

This Court, however, need not reach the question

whether strict scrutiny was applicable here, because the

district court’s ruling must be reversed in any event. As

we show below, the district court made significant legal

errors in applying strict scrutiny to the facts of this case.

Had the district court applied strict scrutiny correctly, it

would have concluded that the challenged districts are

constitutional regardless of whether strict scrutiny was

applicable. The Court can dispose of the case on that basis.

See United States v. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149, 166-167 (1987)

(plurality opinion) (declining to decide whether court-

ordered race-conscious relief was subject to strict scrutiny

since the relief ordered satisfied such scrutiny).

THE STATE’S REDISTRICTING PLAN SATISFIES

STRICT SCRUTINY

This Court recently went out of its way “to dispel the

notion that strict scrutiny is ‘strict in theory, but fatal in

fact.’” Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena, 115 S. Ct.

2097, 2117 (1995). In doing so, the Court recognized that

“[t]he unhappy persistence of both the practice and the

lingering effects of racial discrimination against minority

groups in this country is an unfortunate reality, and

government is not disqualified from acting in response to

it.” Ibid. Accordingly, “[w]hen race-based action is neces

sary to further a compelling interest, such action is

within constitutional restrain ts if it satisfies the ‘narrow

tailoring’ test this Court has set out in previous cases.”

Ibid. The minority opportunity districts at issue in th is

case are narrowly tailored to further Texas’s compelling

interests in complying with Section 2 of the Voting

19

Rights Act and in ameliorating the effects of persistent

racially polarized voting.

A. The State Had A Compelling Interest In Drawing One

Black Opportunity District In Dallas County And One

Black And One Hispanic Opportunity District In

Harris County In Order To Comply With Section 2

Of The Voting Rights Act

1. The State drew Districts 18, 29, and 30 in order to

comply with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. In M iller

v. Johnson, 115 S. Ct. 2475, 2490-2491 (1995), the Court left

open the question whether compliance with the Voting

Rights Act, standing alone, provides a compelling justifi

cation for governmental action. The background to the

enactment of Section 2 and this Court’s prior cases an

swer that question and demonstrate that a State has a

compelling interest in complying with Section 2.

Congress adopted the Voting Rights Act in 1965 “to

banish the blight of racial discrimination in voting, which

ha[d] infected the electoral process in parts of our country

for nearly a century.” South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383

U.S. 301, 308 (1966). After a thorough investigation,

Congress determined that earlier attempts to remedy

racial discrimination in voting had failed because of “unre

mitting and ingenious defiance of the Constitution” in

some parts of the country. Id. at 309. Congress therefore

adopted “sterner and more elaborate measures,” ibid . ,

including Section 5’s requirement that covered ju ris

dictions preclear their voting changes with federal

officials and Section 2’s requirement that all jurisdictions

avoid abridgements of the right to vote on the basis of race.

Id. at 315-316.

When it subsequently extended the Voting Rights Act

in 1982, Congress concluded that its provisions continued

to be necessary in order to prevent voting discrimination.

20

See S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 9-10 (1982). At

that time, Congress heard evidence that minority group

members continued to experience direct impediments to

voting, including physical intimidation of voters and candi

dates, reregistration requirements, voter purges, changes

in the location of polling places, and inconvenient voting

and registration hours. Id. at 10 n.22 (citing testimony

from House and Senate hearings). Congress also heard

evidence that, between 1970 and 1980, discrimination in

voting had become much more sophisticated and involved

purposeful efforts to dilute minority voting strength

through such practices as annexations, the use of at-large

elections, majority vote requirements, numbered places,

and the shifting of district boundary lines. Id. at 10.

Finally, Congress was presented with “overwhelming

evidence” that racial politics continued to dominate the

political process in some communities. Id. at 33-34.

In response to those continuing threats to minority

voting rights, Congress extended Section 5 of the Act

and amended Section 2 to prohibit voting practices that

have discriminatory “results.” 42 U.S.C. 1973(a). Con

gress provided that discriminatory results occur when

minority group members have “less opportunity than

other members of the electorate to participate in the

political process and to elect representatives of their

choice.” 42 U.S.C. 1973(b). Congress recognized that com

pliance with that new statutory prohibition would

sometimes require taking race into account in drawing

district lines. S. Rep. No. 417, supra, at 30-34. Congress

believed, however, that such a prohibition was necessary;

it concluded that prohibiting practices with discrim

inatory results was essential to prevent intentional

discrimination that would otherwise “go undetected,

uncorrected and undeterred” because of the inordinate

difficulty of proving a discriminatory purpose. Id. at 36,

21

40. Congress also concluded that “voting practices and

procedures that have discriminatory results perpetuate

the effects of past purposeful discrimination.” Id. at 40.

Congress’s conclusions were supported by abundant

evidence. As one court has stated, “[ejmpirical findings fcy

Congress of persistent abuses of the electoral process, and

the apparent failure of the intent test to rectify those

abuses, were meticulously documented and borne out by

ample testimony.” Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325, 347

(E.D. La. 1983) (three-judge court). Congress therefore

enacted the amendment to Section 2 to further its

compelling interest in eliminating racial discrimination

and its effects. See Adarand , 115 S. Ct. at 2117; City of

Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469, 503-504, 509

(1989); United States v. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149, 167 (1987)

(opinion of Brennan, J.); id. at 186 (Powell, J., concurring);

Local 28 of Sheet Metal Workers’ In t’l A ss’n v. EEOC, 478

U.S. 421, 480 (1986) (opinion of Brennan, J.); id. at 485

(Powell, J., concurring); Bob Jones Univ. v. United States,

461 U.S. 574, 604 (1983).

This Court’s decisions firmly establish that Congress

had authority under the Constitution to enact the 1982

amendment to Section 2. This Court has made clear that,

even though the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments

themselves prohibit only intentional discrimination, Con

gress has broad authority under Section 5 of the

Fourteenth Amendment and Section 2 of the Fifteenth

Amendment to ban voting practices that have discrimina

tory effects. City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156,

173-178 (1980) (upholding Section 5 prohibition against

retrogressive voting changes); Oregon v. Mitchell, 400

U.S. 112 (1970) (upholding nationwide ban on literacy

tests); Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) (up

holding ban on use of literacy tests as applied to citizens

educated in Puerto Rico); South Carolina v. Katzenbach,

22

383 U.S. at 334 (upholding the suspension of literacy tests

in certain jurisdictions). In particular, Congress may

proscribe voting practices with discriminatory effects

when they either pose a “risk of purposeful discrim

ination” or “perpetuate!] the effects of past discrim

ination.” City of Rome, 446 U.S. at 176, 177; South

Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. at 334. Congress con

cluded that both of those dangers were present here. The

amendment to Section 2 therefore falls within Congress’s

broad powers to enforce the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments. Jones v. City of Lubbock, 727 F.2d 364, 372-

375 (5th Cir. 1984) (upholding the constitutionality of

Section 2); United States v. Marengo County Comm’n,

731 F.2d 1546, 1556-1563 (11th Cir. 1984) (same).

The principles underlying the Court’s decisions in

Shaw v. Reno, 113 S. Ct. 2816 (1993), and M iller v.

Johnson, supra, do not cast doubt upon the constitu

tionality of Section 2. The Court explained in Shaw and

M iller that government action that “separated] its citi

zens into different voting districts on the basis of race”

is suspect because it may be based on “the offensive and

demeaning assumption that voters of a particular race,

because of their race, ‘think alike, share the same political

interests, and will prefer the same candidates at the

polls.’” M iller, 115 S. Ct. at 2486 (quoting Shaw, 113 S.

Ct. at 2827). Section 2 makes no such assumptions.

Gingles, 478 U.S. at 46. It requires race-based districting

only when there is empirical evidence that minority voters

in the particular area are in fact politically cohesive and

that the majority in fact usually votes as a bloc to defeat

the minority’s preferred candidates. Crowe v. Emison,

113 S. Ct. 1075, 1085 (1993). Section 2 therefore does not

require a State to act on the basis of the stereotypes that

Shaw and Miller condemn.

23

Because Section 2 is a constitutional exercise of Con

gress’s authority to eliminate racial discrimination and

its effects, state compliance with its requirements fur

thers that same compelling interest. Thus, when Section

2 requires the drawing of minority opportunity districts,

the State has a compelling interest in drawing such

districts.

2. In order to show that it had a compelling interest in

drawing minority opportunity districts so as to satisfy

Section 2, a State is required to show that it had “a strong

basis in evidence of the harm being remedied.” M iller, 115

S. Ct. at 2491; Croson, 488 U.S. at 500. That standard is

satisfied by evidence that provides a “reasonable basis to

believe” that the failure to create the districts would

violate Section 2. M iller, 115 S. Ct. at 2492.

The “strong basis in evidence” standard ensures that

government actors engaging in race-conscious activity do

so only for well-founded reasons. See Johnson v. Trans

portation Agency, 480 U.S. 616, 652-653 (1987) (O’Connor,

J., concurring in the judgment); Wygant v. Jackson Bd. o f

Educ., 476 U.S. 267, 290-291 (1986) (O’Connor, J., con

curring in part and concurring in the judgment). At the

same time, it promotes voluntary compliance with the law

by giving States a margin of safety against the “competing

hazards” of liability to minorities if they do not create

minority opportunity districts and liability to others if

they do. Id. at 291 (O’Connor, J., concurring in part and

concurring in the judgment). The need to provide such a

margin of safety is particularly strong in redistricting,

for “the States must have discretion to exercise the po

litical judgment necessary to balance competing in ter

ests” in the districting process. M iller, 115 S. Ct. at 2488.

3. This Court has not yet decided what constitutes a

strong basis in evidence for a State’s belief that Section 2

requires it to draw minority opportunity districts. This

24

Court’s Section 2 cases, however, furnish substantial

guidance on that issue. In Gingles, the Court held that

plaintiffs challenging multimember districts under Sec

tion 2 must establish three preconditions: that the mi

nority group “is sufficiently large and geographically

compact to constitute a majority in a single-member

district”; that the minority group “is politically cohesive”;

and that “the white majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to

enable it—in the absence of special circumstances * * *

—usually to defeat the minority’s preferred candidate.”

478 U.S. at 50-51. The Court has subsequently held that

those same preconditions apply to challenges to single

member district plans. See Growe, 113 S. Ct. at 1084.

After establishing the three Gingles preconditions, plain

tiffs must also prove vote dilution from the totality of

circumstances. Johnson v. DeGrandy, 114 S. Ct. 2647,

2657-2658 (1994).

In DeGrandy, the Court held that, in a single

member district case, the compactness and numerosity

precondition “requires the possibility of creating more

than the existing number of reasonably compact d istric ts

with a sufficiently large minority population to elect

candidates of its choice.” 114 S. Ct. at 2655. The Court

left open the question which characteristics of the

minority population are relevant in deciding whether the

minority group could constitute a majority (e.g., age,

citizenship). Id. at 2655-2656. It also left open the related

question whether the first precondition can be satisfied by

proof that the minority group could constitute a sizable

minority (rather than a majority) in a district and could

elect candidates of its choice by attracting some cross

over votes. Id. at 2656. Those questions had been reserved

in prior cases as well. See Growe, 113 S. Ct. at 1083 n.4

(noting that lower courts have looked to voting population

rather than to total population to determine whether the

25

minority could constitute a' majority and that Gingles

refers to voting population, but reserving the question);

Voinovich v. Quilter, 113 S. Ct. 1149, 1154-1155 (1993)

(reserving question whether minority that could not

constitute a majority but could nevertheless elect can

didates of its choice in an alternative district can state a

Section 2 claim); Growe, 113 S. Ct. at 1084 n.5 (same);

Gingles, 478 U.S. at 46 n.12 (same).

In DeGrandy, the Court also made clear that the

presence or absence of “substantial proportionality” be

tween the number of majority-minority districts and

minority members’ share of the relevant population is a

significant factor in assessing the totality of circum

stances. 114 S. Ct. at 2658; id. at 2664 (O’Connor, J., con

curring) (proportionality is always relevant to a vote

dilution claim, but never dispositive). If a State’s plan

affords substantial proportionality, it may be difficult for

plaintiffs to establish that they have been denied an equal

opportunity to participate and elect representatives of

their choice. Id. at 2658-2659. On the other hand, evidence

that a State’s plan leaves minority group members

substantially underrepresented when compared to their

percentage in the relevant population may provide strong

evidence of vote dilution. Id. at 2664 (O’Connor, J.,

concurring).

In light of Gingles and DeGrandy, and the continuing

uncertainty concerning a State’s precise Section 2 obli

gations, a State has a strong basis in evidence for

believing that Section 2 requires it to create minority

opportunity districts when: (1) members of the minority

group are sufficiently numerous and concentrated to have

the “potential to elect” candidates of their choice in a

reasonably compact district (even if they would not

constitute an absolute voting majority), Gingles, 478 U.S.

at 50 n.17; (2) the minority group is politically cohesive; (3)

26

whites engage in significant bloc voting; and (4) the failure

to create a minority opportunity district would leave

minority group members substantially underrepresented

when compared to their percentage in the relevant

population. There may be other circumstances in which

the State could demonstrate a firm basis in evidence

for creating minority opportunity districts, but proof of

those four factors ordinarily will be sufficient. A State

cannot be expected to make the same totality-of-the-

circumstances inquiry at the time it redistricts that a

court is able to make after an adversary trial. Nor should

the State be prevented from resolving uncertain Section 2

issues in favor of the reading that is more, rather than

less, protective of minority voting rights.

4. Texas had a strong basis in evidence for believing

that Section 2 required it to draw one black opportunity

district in Dallas County and one black and one Hispanic

opportunity district in Harris County.

a. In Dallas County, it was possible to draw a reason

ably compact district with a sufficiently large black

population to provide black voters an opportunity to elect

the candidates of their choice. Then-state Senator Eddie

Bernice Johnson presented to the legislature a plan con

taining such a district centered in South Dallas with a

44% black population. J.A. 139. The district court found

that Johnson’s district was “truly compact and contigu

ous” because it was located in a compact geographical

area, kept identifiable neighborhoods intact, and did not

split precincts. J.S. App. 78a. The evidence also showed

that Johnson’s district would have afforded blacks an

opportunity to elect a representative of their choice. 5 Tr.

21; J.A. 234 & n.21. The Owens-Pate plan considered by

the legislature also contained a reasonably compact black

opportunity district. J.A. 141. The existence of those two

alternative districts established that the State had a

27

strong basis for believing that the first Gingles pre

condition would be satisfied if it failed to draw a black

opportunity district in Dallas County.

Texas also had a strong basis for believing that the

second and third Gingles preconditions—black cohesion

and white bloc voting—were satisfied in Dallas County.

The State acted against the backdrop of a long history of

judicial findings that polarized voting has existed in

Dallas County. See, e.g., White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755,

765-767 (1973); Lipscomb v. Wise, 399 F. Supp. 782, 785-786

(N.D. Tex. 1975), rev’d, 551 F.2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1977), rev’d,

437 U.S. 535 (1978). Indeed, just one year prior to the 1991

redistricting, a federal district court invalidated the

election scheme for the Dallas City Council under Section

2, finding, on the basis of an exhaustive analysis, that

black voters in Dallas were politically cohesive and that

white bloc voting usually defeated the candidates preferred

by blacks. W illiams v. City of Dallas, 734 F. Supp. 1317,

1387-1394 (N.D. Tex. 1990). Expert testimony presented

by the State in the present case confirmed the existence

of racially polarized voting in Dallas County both in the

areas covered by District 30 and in the areas not included

in that district. 4 Tr. 187; see also J.A. 227. Legislators

involved in redistricting were aware of the findings in

W illiam s and of the persistence of racially polarized vot

ing in Dallas County. Lawson Exhs. 7,11; J.A. 251.

Finally, if the State had not drawn a black opportunity

district in Dallas County, blacks in that area would have

been very substantially underrepresented when compared

to their percentage of the Dallas County population. Even

though blacks constitute 20% of the Dallas County

population and the Dallas County population is sufficient

to support three and one-third congressional districts,

blacks in Dallas County would not have been able to elect a

single representative of their choice. See pp. 6, 7-9, supra.

28

The State therefore had a strong basis in evidence for

its belief that Section 2 required it to create a black

opportunity district in Dallas County.2

b. The State also had a strong basis for believing that

Section 2 required it to draw one black and one Hispanic

opportunity district in Harris County. The State pre

sented evidence that black voters in Harris County were

sufficiently numerous and concentrated to allow the

drawing of one reasonably compact black opportunity

district. See J.A. 197-198. Likewise, the State’s evidence

showed that it was possible to draw a reasonably compact

Hispanic opportunity district in Harris County. See J.A.

199-200. Because many concentrations of black voters in

Harris County are in close proximity to concentrations of

Hispanic voters, those two hypothetical districts overlap.

Given those demographic patterns, it is unclear whether

the State could have drawn both a reasonably compact

black opportunity district and a reasonably compact H is

panic opportunity district simultaneously.

Notwithstanding that uncertainty, Texas had a strong

basis in evidence for concluding that both minority groups

satisfied the first Gingles precondition. Section 2 protects

2 A federal district court held in 1984 that a plan that failed to

draw a majority-black congressional district in Dallas did not violate

Section 2. See S ea m o n v. U pham , No. P-81-49-CA (E.D. Tex. Jan. 30,

1984). The court relied on evidence that black voters had “significant

influence” on elections in the majority-white districts in southern

Dallas County. Slip op. 15-16. At the time of the 1980 redistricting,

however, Dallas County supported less than three districts. U.S. Exh.

1085. Moreover, S ea m o n was decided before the district court had

issued its decision in W illia m s on the extent of racial polarization in

Dallas County. The legislature was entitled to take into account the

fact that the Dallas County population now supports three and one-

third districts and to rely on the more recent W illia m s findings in

concluding that Section 2 now requires a black opportunity district.

29

all racial minority groups and provides States with no

clear basis on which to choose which of two sim ilar

ly situated minority groups to protect from dilution. If

the State had drawn only a black opportunity district, it

would have been vulnerable to a Section 2 suit brought by

Hispanics; if it had drawn only an Hispanic opportunity

district, it would have been vulnerable to a suit brought

by blacks. In that situation, rather than arbitrarily pre

ferring one group over the other, the State reasonably

concluded that its Section 2 responsibilities required it to

provide both black and Hispanic voters an opportunity to

elect their preferred candidates—even if that required a

departure from compactness.

The State had a strong basis to believe that the second

and third Gingles preconditions were satisfied in H arris

County as well. The State’s expert, Dr. Lichtman, con

cluded that elections in what is now District 29 were the

“most extremely polarized” of any he examined-—Hispanic

voters voted for Hispanic candidates 89% of the time, and

Hispanic candidates received only a 5% crossover from

white voters. 4 Tr. 186-187. The area now covered by

District 18 also exhibited a high degree of polarization

between black and white voters. 4 Tr. 187-188; see also J.A.

225-227. Legislators involved in redistricting were well

aware of the history of racially polarized voting in H arris

County. J.A. 251.

The legislators involved in redistricting were also

aware that the black/Hispanic coalition in H arris

County—which had previously enabled black and Hispan

ic voters to elect the candidate of their choice in the

18th District—had begun to disintegrate. As the district

court noted (J.S. App. 22a-23a), the breakdown of the

black/Hispanic coalition had exhibited itself in a series of

divisive local elections beginning in 1989. J.A. 251; Lawson

Exh. 26. Dr. Lichtman’s analysis confirmed that “His

30

panic and black voters did not usually both provide

majority support for minority candidates.” J.A. 228-229.

Texas therefore had a strong basis for concluding that

black voters would lack an opportunity to elect represen

tatives of their choice in a district designed to afford

Hispanics such an opportunity and that Hispanics would

lack an opportunity to elect candidates of their choice in a

district designed to afford blacks such an opportunity. In

contrast to the situation during the previous decade, only

by drawing two minority opportunity districts in H arris

County could the State in 1991 afford each group an

opportunity to elect a representative of its choice.

Finally, if the State had not drawn either an Hispanic or

a black opportunity district in Harris County, blacks and

Hispanics in Harris County would have been very

substantially underrepresented when compared to their

percentage in the Harris County population. Hispanics

make up approximately 23% of the Harris County popula

tion and blacks make up approximately 19% of the H arris

County population, and the population of Harris County is

sufficient to support five districts. Nevertheless, neither

group would have had an opportunity to elect a repre

sentative of its choice if no minority opportunity d istric ts

were drawn. See pp. 6, 9-11, supra. The evidence therefore

establishes each of the prerequisites necessary to support

the conclusion that Texas had a compelling interest in

drawing one black and one Hispanic opportunity district in

Harris County.

5. The district court did not purport to decide whether

Texas had a strong basis in evidence for its conclusion

that Section 2 required it to draw one black opportunity

district in Dallas County and one black and one Hispanic

opportunity district in Harris County. J.S. App. 86a-93a.

The district court held instead that, because the d istricts

actually drawn by the State do not satisfy the Gingles

31

compactness requirement, Section 2 could provide no

justification for drawing those districts. Id. at 89a n.54.

That reasoning is seriously flawed. For a State to invoke

its compelling interest in creating minority opportunity

districts in order to comply with Section 2, there must be

evidence that reasonably compact districts could have been

drawn. A State is not required, however, to enact a plan

that incorporates the geographically compact d istricts

that led it to conclude that Section 2 required it to create

minority opportunity districts in the first place. Shaw v.

H unt, 861 F. Supp. 408, 454 n.50 (E.D.N.C. 1994) (three-

judge court), probable juris, noted, 115 S. Ct. 2639 (1995).

The district court’s contrary view reflects a basic mis

understanding of the Gingles compactness requirement.

Gingles held that Section 2 plaintiffs must show that a

reasonably compact district can be drawn in order to

establish a violation of that provision. 478 U.S. at 50.

Absent such a showing, the Court held, plaintiffs cannot

show that the discriminatory aspects of the existing

election system have caused their inability to elect

candidates of their choice. Id. at 50 n.17. Gingles did not

hold, however, that States are required to remedy

violations of Section 2 by drawing compact districts. Nor

does the statute impose such a requirement. Section 2

prohibits the denial of an equal opportunity to elect

representatives of choice. See 42 U.S.C. 1973(b). So long

as a State’s plan provides that opportunity, Section 2 obli

gations are satisfied; for Section 2 purposes, it does not

m atter whether the State satisfies its statutory obliga

tions by utilizing compact or noncompact districts. See

Upham v. Seamon, 456 U.S. 37, 42 (1982) (per curiam)

(federal court must defer to a State’s remedial plan so long

as it satisfies the substantive requirem ents of federal

law); cf. McGhee v. Granville County, 860 F.2d 110, 120-

121 & n .ll (4th Cir. 1988) (county may remedy violation of

32

Section 2 caused by multimember districts by increasing

the size of the body or through limited voting scheme).

Thus, at the compelling interest stage of the inquiry,

the relevant question under Gingles is whether reason

ably compact minority opportunity districts could have

been drawn. When such districts could have been drawn

and the other preconditions for a strong basis in evidence

are also established, the State has a compelling interest in

drawing minority opportunity districts in order to comply

with Section 2. The question whether the districts the

State then draws to further that interest are drawn in a

permissible way is a question of narrow tailoring.

Because reasonably compact minority opportunity dis

tricts could have been drawn in Dallas and H arris

Counties and the other relevant preconditions for a strong

basis in evidence were established, Texas had a compelling

interest in drawing minority opportunity districts in

order to comply with Section 2.

B. The State Also Had A Compelling Interest In

Drawing One Black Opportunity District In Dallas

County And One Black And One Hispanic

Opportunity District In Harris County In Order To

Counteract The Effects Of Racially Polarized Voting

The State’s decision to draw three districts in Dallas

and Harris Counties in which minority voters would have

an opportunity to elect the candidates of their choice was

supported by an additional compelling interest: the

interest in ameliorating the effects of racially polar

ized voting attributable to past and present racial

discrimination. This Court has recognized that, even

absent a federal statutory duty, a State has a compelling

interest in taking race-conscious action to remedy

identified discrimination within its jurisdiction if it has a

strong basis for believing that its action is necessary to

achieve that remedial purpose. See Adarand, 115 S. Ct. at

2117; Croson, 488 U.S. at 491-493, 509 (opinion of O’Connor,

J.). Thus, a State has a compelling interest in eliminating

the effects of racially polarized voting attributable to past

and present discrimination, even when the Voting Rights

Act does not require such action.

Texas has a long history of racial discrimination in

voting and districting. After the close of Reconstruction,

the state legislature drew district lines in predominantly

black counties in a manner designed to minimize the

effects of black votes in legislative and judicial elections.

St. Exh. 17, at 4. At the turn of the Twentieth Century,

Texas instituted a poll tax, which remained in place until

it was struck down by a federal court in 1966. Texas v.

United States, 384 U.S. 155 (1966) (per curiam); see St.

Exh. 17, at 13. Texas replaced the poll tax with a system

requiring annual voter registration; the new system was

then itself invalidated by a federal court. Beare v. Sm ith,

321 F. Supp. 1100 (S.D. Tex. 1971) (three-judge court), aff’d

sub nom. Beare v. Briscoe, 498 F.2d 244 (5th Cir. 1974);

see J.A. 359; St. Exh. 17, at 13. Texas also maintained a

whites-only primary system for over half of this Century;

the State abandoned that system only after four separate

decisions of this Court invalidated different forms of that

system. Terry v. Adam s, 345 U.S. 461 (1953); Sm ith v.

Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944); N ixon v. Condon, 286 U.S.

73 (1932); N ixon v. Herndon, 273 U.S. 536 (1927); see J.A.

359; St. Exh. 17, at 5-12. In 1973, this Court upheld a

district court’s conclusion that a state-wide legislative

reapportionment employing multimember districts pur

posefully diluted black and Hispanic voting strength

in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. White v.

Regester, 412 U.S. 755. Since that decision, courts have

found that various levels of state government have diluted

black and Hispanic voting strength in violation of Section

34

2. St. Exh. 17, at 18-23. And as recently as 1991, Texas’s

redistricting plan for the State House of Representatives

deliberately fragmented and packed the Hispanic pop

ulation in certain areas of the State, which led the

Attorney General to interpose an objection under Section

5. J.A. 365-366.

Texas could reasonably believe that the significant

racial polarization present in the State is, at least in part,

a consequence of that long and deplorable history of voting

discrimination. The State could also have reasonably be

lieved that the persistent and severe pattern of racially

polarized voting was “circumstantial evidence of racial

bias operating through the electoral system to deny

minority voters [in Dallas and Harris Counties] equal

access to the political process.” N ipper v. Sm ith, 39 F.3d

1494, 1524 (11th Cir. 1994) (en banc) (plurality opinion),