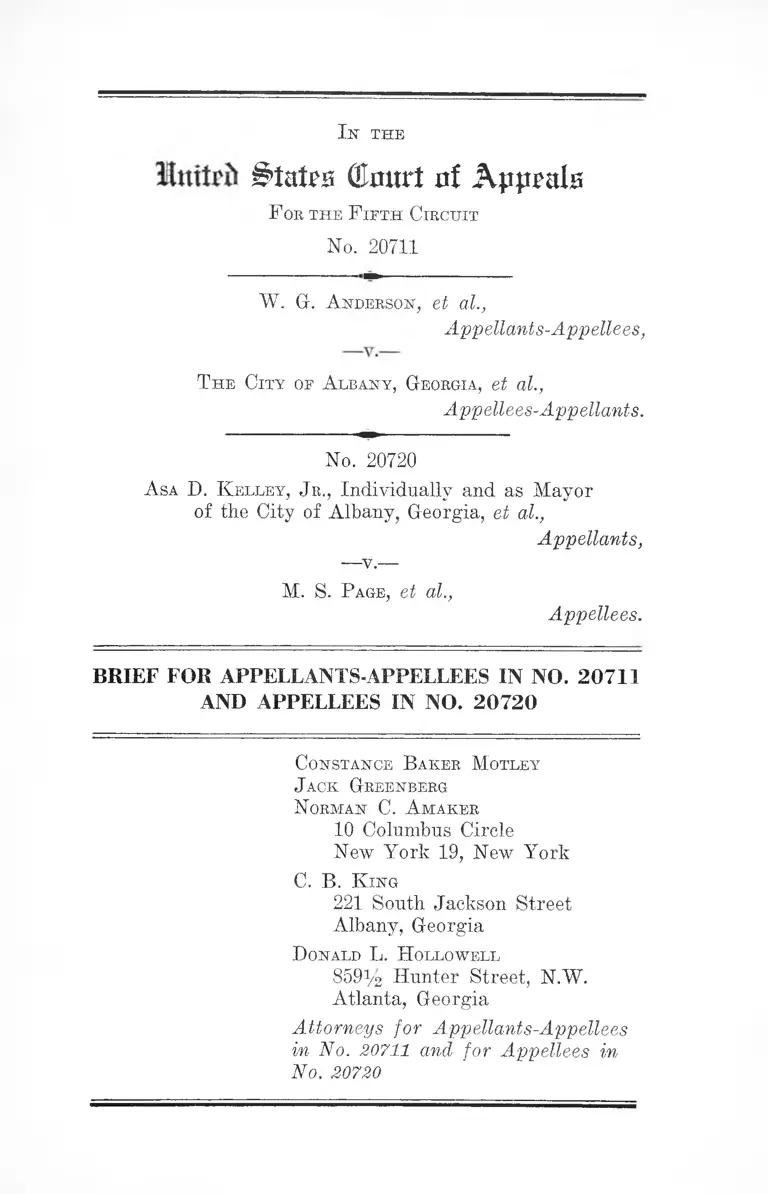

Anderson v. City of Albany, GA Brief for Appellants-Appellees in No. 20711 and Appellees in No. 20720

Public Court Documents

January 3, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Anderson v. City of Albany, GA Brief for Appellants-Appellees in No. 20711 and Appellees in No. 20720, 1964. fdb87545-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/05a28735-8cea-4a6f-8db8-5b68cef045ea/anderson-v-city-of-albany-ga-brief-for-appellants-appellees-in-no-20711-and-appellees-in-no-20720. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

States GJmtrt xif Appmis

F ob the F ieth Circuit

No. 20711

W . G. A nderson, et al.,

Appellants-Appellees,

T he City of Albany, Georgia, et al.,

Appellees-Appellants.

No. 20720

A sa D. K elley, J r., Individually and as Mayor

of the City of Albany, Georgia, et al.,

Appellants,

— v.---

M. S. P age, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS-APPELLEES IN NO. 20711

AND APPELLEES IN NO. 20720

Constance B aker Motley

J ack Greenberg

N orman C. A maker

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

C. B. K ing

221 South Jackson Street

Albany, Georgia

D onald L. H ollowbll

859V2 Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants-Appellees

in No. 20711 and for Appellees in

No. 20720

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case .................................................. 1

Specification of Errors ................... 15

A r g u m e n t ................................. 18

I. The Court Below Erred in Denying Appellants

in Anderson, No. 20711, the Injunctive Relief to

Which They Were Entitled by the Evidence__ 18

II. The Court Below Did Not Err in Refusing to

Grant the Injunction Requested by City Offi

cials in Kelley, 20,720 ................................. ..... 34

III. The Court Below Did Not Err in Refusing the

Injunction Requested by City Officials on Their

Counterclaim in Anderson, 20,711__________ 37

IV. The Court Below Did Not Err in Refusing to

Grant Injunctive Relief Requested by City Offi

cials Because These Officials Came Into Equity

With Unclean Hands ........................................ 39

C o n clu sio n ........................................................................................ 41

T able of Cases

Aelony v. Pace, No. 530 N. D........ ................. .............. 4

American Federation of Labor v. Swing, 312 U. S.

321 ____ ______ __________ __ _______ _________ 25

Anderson v. City of Albany, 321 F. 2d 649 .... .....2, 3, 5,14,

17,19, 23, 39

Bailey v. Patterson, 323 F. 2d 201 .................. ............. 23

Bakery and Pastry Drivers & Helpers Local v. Wohl,

315 U. S. 769 25

11

PAGE

Brantley v. Skeens, 266 F. 2d 447 (D. C. Cir. 1959) ..... 40

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ........... ......... .........30, 39

Cafeteria Employees Union v. Angelos, 320 U. S. 293 .. 25

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 .................. ......28, 33

Congress of Racial Equality v. Clemmons, 323 F. 2d

54 ................................. ........... .......... ................. .....36, 37

Congress of Racial Equality v. Douglas, 318 F. 2d 95 .... 30

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ...................... .................30, 39

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 __ ___25, 26, 27,

28, 30, 33, 39

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315................ ........... . 28

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44 ___ ___ ___ 26, 30, 33

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 ________ ___ ____ 26

Guadiosi v. Mellon, 269 F. 2d 873 (3rd Cir. 1959) ....... 40

Hague v. C. I. O., 307 U. S. 496 ...................................30, 32

Harris v. Pace, No. 531 (N. D. Ga.) ........... ..... ........... . 4

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 ................................... 4

Hughes v. Superior Court of California, 339 U. S. 460 .. 25

Keystone Driller Co. v. General Excavator Company,

290 U. S. 240 ...................................... An

Milk Wagon Drivers Union v. Meadowmoor Dairies,

312 U. S. 287 .............. .................. . a

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 .......................... ..... 26

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 ........................... ...... 26

New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Co., 303 U. S.

552 .................................. 25

Ill

PAGE

Precision Company v. Automotive Company, 324 IT. S.

806 ............................................ ......... ........................ 40

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313 ......... .................... ......... 32

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. 8. 1 ............................28, 33

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88........ .............. ......... 25

United States v. City of Jackson, 318 F. 2d 1 ........... 22

United States v. Oregon State Medical Society, 343

U. S. 326 .................................................. .......... ’...... 19

United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U. S. 629 ........... 21

Walker v. Galt, 171 F. 2d 613 (5th Cir. 1948) ............... 40

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 ...... ........... ......... ..... . 4

S tatutes I nvolved

28 U. S. C. A. §§1331, 1343(3) ............. ............. ...3, 5, 35, 36

42 U. S. C, §1983 ........................ ......................... .... ..... 3

42 U. S. C. A. §1985(3) ........ .............................. 5, 35, 36, 37

F. R. C. P., Rule 23(a)(3) ........................... ................. 3

Georgia Code, §26-530 ........................ ................... ....... 39

Georgia Code, §26-902 ....... ........................................... 4, 39

Georgia Code, §26-5301 ............. ................................. 4

City Code of Albany, Chap. 11, §6 ...... 20

City Code of Albany, Chap. 14, §7 ............ .... .............. 20

City Code of Albany, Chap. 24, §35 .........................16, 20, 31

City Code of Albany, Chap. 24, §36............................... 20

I n the

lutteft ( to r t of Appals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 20711

W . G. A nderson, et al.,

Appellants- Appellees,

T he City of A lbany, Georgia, et al.,

Appellees-Appellants.

No. 20720

A sa D. K elley, J r ., Individually and as Mayor

of the City of Albany, Georgia, et al.,

—v.—

Appellants,

M. S. P age, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS-APPELLEES IN NO. 20711

AND APPELLEES IN NO. 20720

Statement of the Case

General Summary

Two appeals and one cross-appeal are here involved.

The first appeal, No. 20711, which arises out of attempts

by Negro citizens of Albany, Georgia to desegregate facili

ties open to the public, now presents for this court’s resolu-

2

tion the question reserved in an earlier decision which arose

out of the same controversy, Anderson v. City of Albany,

321 F. 2d 649 (July 26,1963, reh. den. Sept. 12, 1963). That

question is whether peaceful protest demonstrations, en

masse and in small groups, against both official and private

racial discrimination, in many areas of community life,

may be thwarted by arrests and other forms of police ac

tivity “under the guise of constitutionally worded statutes

and ordinances” in the name of preserving the public peace

and safety (321 F. 2d at 647-658).

The earlier Anderson case dealt with the failure of the

court below to grant injunctive relief against state decreed

racial segregation in public recreational, library, and audi

torium facilities and in privately owned transportation

facilities, taxis and theatres. In its decision, this court

ordered an end to state enforced segregation in those

facilities and required the District Court to grant injunc

tive relief against arrests for attempting to use these pub

lic and private facilities required by law to be segregated.

That injunction has been issued, ending that part of the

controversy in Albany, Georgia. The remainder of the

controversy is involved in this first appeal.

Appellants in the first appeal, No. 20711, were plaintiffs

below. However, they are also appellees in No. 20711

because defendants below filed a counterclaim the denial

of which they are also appealing. Appel!ants-Appellees in

No. 20711 are also appellees in No. 20720, having been de

fendants below in a suit for injunctive relief filed by Albany

city officials, the same parties who counterclaimed in No.

20711 and whose counterclaim presented the same case as

their claim in No. 20720.

All parties have appealed from an opinion and order of

the United States District Court, Middle District of

Georgia, Albany Division, the Honorable J. Robert Elliott,

3

issued on June 28, 1963, in which their respective prayers

for injunctive relief were denied in an opinion dispositive

of both cases (R. Anderson 26; R. Kelley 35).1 These

cases were consolidated on this appeal by order of this

court of October 24, 1963.2 This brief is filed on behalf

of appellants-appellees in Anderson and appellees in Kelley.

Summary of Proceedings in Anderson, e l al.

v. City of Albany, No. 20711

The complaint was filed on July 24, 1962 as a class action

pursuant to F. R. C. P., Rule 23(a)(3), invoking juris

diction under 28 IJ. S. C. §1343(3) and under the Civil

Rights Acts, 42 U. 8. C. §1983 (R. Anderson 1). Plaintiffs

alleged that they, and the members of their class, had

peacefully demonstrated against: 1) state-enforced racial

segregation in publicly owned and operated facilities and

privately owned public transportation facilities and thea

tres, and 2) against enforcement of racial discrimination in

drug and department stores opened to the general public.

Plaintiffs alleged further that they had been arrested, on

various charges under Albany ordinances, on account of

their protest demonstrations (R. Anderson 5-7). Addi

tionally, the complaint averred that plaintiffs had sought

a permit and cooperation of the police for a peaceful,

orderly demonstration which had been denied; and that a

temporary restraining order designed to halt their protest

1 The printed record in Anderson, et al, v. City of Albany, No.

20711, will be referred to hereafter as R. Anderson----- while the

printed record in Kelley, et al. v. Page, No. 20720, will be referred

to as R. Kelley----- . The transcript of testimony already on file in

this Court (having been filed with the earlier Anderson appeal)

will be cited as T. Vol. ----- , ----- .

2 While decision of the earlier Anderson case was pending in this

Court, appellants moved to consolidate these appeals with that

case. The Court denied this motion because it had been filed after

oral argument and consideration of that case but granted the

parties the right to use the record in the case in these appeals

(Order filed July 18, 1963, in Anderson, No. 20501).

4

activity had been sought by city officials and had issued

without notice on July 20, 1962, following plaintiffs’ re

quest for police cooperation in a proposed demonstration

(R. Anderson 6-7). Accordingly, plaintiffs prayed the is

suance of an injunction securing the right to peacefully

demonstrate against segregation and discrimination which

right, it was declared, was protected by the First Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States and the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment (R. Anderson 2). Annexed to the complaint

was a notice for preliminary injunction (R. Anderson 11).

Thereafter, on July 31, 1962, defendants filed an answer

and counterclaim (designated as a cross claim) alleging

that plaintiffs had conducted mass demonstrations, mass

picketing, and boycotts in the City of Albany; had caused

large numbers of people to congregate on the public streets;

had blocked and obstructed some of the streets in the

City; had caused traffic to become congested; and had

generally constituted a hazard to public safety. Defendants

further claimed that plaintiffs’ acts violated a number of

statutes (two of which have since been declared unconstitu

tional),3 and city ordinances set forth in the counterclaim.

Defendants, therefore, prayed interlocutory and permanent

injunctive relief against plaintiffs (R. Anderson 15-24).

Hearing on appellants’ motion for preliminary injunc

tion commenced on August 30, 1962, at which time the case

was consolidated for purposes of trial with the Anderson

ease, previously decided by this Court, and the Kelley case,

3 Ga. Code §26-5301 (unlawful assemblies and disturbing the

peace) and Ga. Code §26-902 (attempts to incite insurrection), two

of the statutes which the city claimed were being violated, were

declared unconstitutional by a three-judge District Court on No

vember 1, 1963, in Aelony v. Pace, No. 530 and Harris v. Pace, No.

531 (N. I). Ga.) the court basing its decision on Wright v. Georgia,

373 U. S. 284 and Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242.

5

here. Testimony was concluded at the end of the day on

August 31, 1962, resumed on September 26, 1962, and con

cluded on that date.

On June 28, 1963, the District Court wrote an opinion

in which it made no specific findings in this case on either

the main claim or the counterclaim but, nevertheless, de

nied all injunctive relief.

Appeal was taken to this court by both parties via sep

arate notices of appeal filed on July 12, 1963 (R. Anderson

37) and July 16, 1963 (R. Anderson 40), respectively.

Summary of Proceedings in

Kelley v. Page, No. 20720

The complaint in this case was filed on July 20, 1962, four

days earlier than the complaint in the Anderson cases.

Jurisdiction was alleged under 42 U. S. C. §1985(3) and 28

U. S. C. §§1343 and 1331. The complaint in all significant

particulars alleged the substance of the matter contained

in the counterclaim filed in the Anderson case, supra,

namely, that defendants by their activities were disrupting

the public peace of the City of Albany and were in viola

tion of the same state statutes and city ordinances. Ac

cordingly, plaintiffs prayed that a temporary restraining

order, interlocutory and permanent injunction issue to

prevent the defendants:

“from continuing to sponsor, finance, incite or encourage

unlawful picketing, parading or marching in the City

of Albany, from engaging or participating in any un

lawful congregating or marching in the streets or other

public ways of the City of Albany, Georgia; or from

doing any other act designed to provoke breaches of

the peace or from doing any act in violation of the

ordinances and laws hereinbefore referred to.” (R.

Kelley 1-10.)

6

The complaint was filed sometime during the day of July

20, 1962, and at 10:55 P. M. that night District Judge

Elliott issued a temporary restraining order (returnable

nine days later) in accordance with the prayer of the

complaint (E. Kelley 13). After signing the order Judge

Elliott left the state (E. Kelley 20) but on July 24, 1962,

Chief Judge Tuttle of this Court vacated the order pend

ing a hearing and ruled that the court below was clearly

without jurisdiction of the cause of action (E. Kelley 20).

Appellees’ motion to dismiss this complaint on juris

dictional and other grounds when the case came on for

hearing in the court below was denied (T. Vol. I, 1 A).

An amendment to the complaint was filed on July 31, 1962

(E. Kelley 24), in which plaintiffs alleged additional matter

consonant with allegations made in the complaint.

Defendants answered on August 6, 1962 (E. Kelley 26),

denying the allegations of illegal conduct contained in the

complaint and its amendment and claiming that their con

duct was only that of peaceful protest against the segrega

tion laws and practices of the City of Albany and that their

activities had not violated any valid state law or city

ordinance. Defendants asked that plaintiffs’ request for

injunctive relief be denied and the action dismissed be

cause of lack of jurisdiction (E. Kelley 31).

Testimony in the case commenced on July 30, 1962, con

tinued through August 3, recessed until August 7, and

ended August 8, 1962. The record of this testimony was

considered by the District Court in its decision of all three

cases pursuant to its consolidation of the cases for trial.

Thus, in actual effect, the hearing in this case was not

concluded until September 26, 1962 (see supra). By agree

ment of counsel for both parties, at the conclusion of all

testimony on September 26, 1962, the District Court con-

7

sidered all testimony taken from July 30, 1962-September

26,1962, as that offered on a final hearing.

In its June 27th opinion and order, the District Court

denied the prayer for injunctive relief and refused to rule

on defendants’ prayer to dismiss on the ground that de

fendants’ counterclaim in Anderson (20711) contained sub

stantially the same allegations and had asked for substan

tially the same relief as the complaint in this case and

since the court clearly had jurisdiction of the Anderson

case, decision of the claim of nonjurisdiction in this case

was unnecessary (E. Kelley 41; R. Anderson 32).

Notice of Appeal was filed on July 16, 1963 (E. Kelley

46).

Summary of Evidence

1) Formation and Purpose of the Albany Movement

The movement for desegregation in Albany was spear

headed by the Albany Movement, an unincorporated asso

ciation of individuals, primarily Negroes, resident in Al

bany, Georgia (T. Vol. I, 2A-3A; T. Vol. Ill, 637A-638A;

T. Vol. V, 120B-121B). Its objectives are the desegregation

of all publicly owned or operated facilities and privately

owned facilities patronized by Negroes in the City of Al

bany, nondiscriminatory representation of Negroes on petit

and grand juries, and increased public and private em

ployment opportunities for Negroes (PI. Exh. I, 20501;

T. Vol. V, 25B-26B). These objectives are to be attained

through peaceful means (T. Vol. V, 139B). Force and

violence are definitely eschewed (T. Vol. Ill, 664A).

2) Methods Utilised to Achieve Objectives

The mass protest movement in Albany commenced upon

the failure of Negro leaders to negotiate the Negro com

munity’s many grievances with city officials and local mer-

8

chants. Appellant, Dr. W. G. Anderson, president of the

Albany Movement, testified that on several occasions he

and others petitioned the Mayor and city officials in vain to

initiate desegregation of public and private facilities (T.

Vol. V, 55B-56B, 59B, 83B, 103B-105B). The Movement’s

public protect activities did not begin until these attempts

had proven fruitless, and even while the protest demon

strations were going on attempts to negotiate continued.

In short, the Albany Movement chose the means of peace

ful public protest in an attempt to achieve that which they

had been unable to achieve by approaching city officials.

3) The Movement’s Protest Activities and the

City’s Efforts to Crush Them

Though random protests had occurred prior to November

19, 1961 (T. Vol. V, 120B), the major organized demon

strations in which members of the Albany Movement took

part began in November 1961 (T. Vol. V, 116B). The dem

onstrations took the form of mass meetings in churches,

walks to City Hall, prayer vigils in front of City Hall,

and picketing of segregated public and private facilities.

The testimony with respect to these various protest in

cidents and the arrests which followed is prolix—spread

over six volumes—and reveals that protests occurred in

small spontaneous groups, as well as larger organized dem

onstrations. However, what emerges from a distillation of

the record is an unmistakable determination on the part

of the police, the Mayor, the City Manager and other city

officials to prevent any public protest no matter how mani

fested on the part of the Albany Movement against racial

segregation. One thousand one hundred arrests were made

over a period of several months involving 450 persons

charged with various offenses such as parading without a

permit, refusing to obey an officer, disorderly conduct, etc.

9

a) First, a summary of the small, sporadic protest ac

tivity which resulted in arrests:

On one occasion Negroes attempted to use the white

public library, found the library doors locked in anticipa

tion of their coming, proceeded to kneel and pray on the

library steps and “the policemen came and literally carried

[them] away” (T. Vol. V, 110B-111B). A Negro girl was

arrested for refusing to move to the back of a local city

bus when the buses were in operation (T. Vol. V, 155B-

162B; Vol. VI, 199B-211B). A Negro man was arrested

when he and a companion went into the white restaurant in

the Trailways Bus Terminal in Albany (T. Vol. V, 167B-

169B). After the I. G. C. ruling of November 1, 1961, bar

ring segregation, Negroes were repeatedly arrested in the

white waiting room of the Trailway Bus station (T. Vol.

I, 153A-155A; 159A-160A; 162A). A cab driver was ar

rested for carrying white passengers, without charge, who

were stranded on the outskirts of the City and requested

that he drive them into the City. This driver was convicted

and fined (T. Vol. V, 96B-102B). Negro high school stu

dents were arrested by the Chief of Police when they con

ferred with the owner of a local theatre about the owner’s

segregation policy which resulted in the students having

to leave their seats on one occasion to make room for the

white patrons in the Negro section (T, Vol. V, 178B-185B).

There was a great deal of testimony in the record with

respect to a picketing incident involving appellants Ander

son, Slater King, Harris and Jackson that occurred in

March of 1962 in the 100 block of North Washington Street

in Albany. Two of the above-named appellants were on

one side of the street and two on the other side (T. Vol.

V, 149B-151B). Dr. Anderson was carrying a sign reading

“walk, live and spend in dignity” (T. Vol. IV, 889A). An

derson was approached by Assistant Chief of Police, Leslie

10

Summerford, and told that he and the other three pieketers

would have to stop walking and move on or else be arrested.

Anderson was told by Summerford that a ease would be

made out against him, and when finally, the group was

placed under arrest, Anderson was told when he asked

“on what charge” that “well, we will get a charge” (T. Yol.

V, 149B). Assistant Chief Summerford testified that he

did in fact tell Anderson that he would have to make out a

case against him (T. Yol. VI, 274B), and he also testified

that Anderson and the three others were doing nothing

more than walking, “not especially talking” (T. Vol. VI,

279B), that there was no crowd to speak of (T. Vol. VI,

285B), no people standing in the recesses or entrances to

doorways at the scene (T. Vol. VI, 290B), and that the

only crowd of any size that collected did not collect until

the arrests were made (T. Vol. VI, 289B).

This incident was typical of others. Other Negroes were

arrested for similar picketing in small numbers (T. Vol. I,

249A). Several others were arrested for participating in

a prayer vigil in front of City Hall (T. Vol. I, 144A-145A,

146 A).

The record of these incidents testify not only to the fact

that these demonstrations were both peaceful in intent and

in fact but also testify to the fact that there was no public

need for the kind of police conduct that was arrayed against

the protestors.

b) The following is a summary of the mass protest

activity which resulted in arrests:

On December 12, 1961, some 267 Negroes marched from

a church to City Hall in a column of twos. They marched

close to the curb, leaving a large portion of the street

unobstructed for normal pedestrian traffic (Def. Exh. 21).

They were singing freedom songs. There were no threats,

11

intimidation, fisticuffs or incidents of any kind (T. Yol. I,

48A, 179A, 191A, T. Vol. I, 47A). No businesses were

required to close (T. Yol. I, 48A-49A). No person was

prevented from entering a building (T. Vol. I, 181A). The

situation was under control at all times (T. Yol. I, 206A).

On December 13, 1961, another march involving approxi

mately 100-200 persons occurred (T. Vol. I, 54A). They

marched two abreast in close orderly fashion, remaining

close to the building line. Pedestrian traffic was unimpeded

and there was no commotion or disturbance (Def. Exh. 23

(a-p); Def. Exh. 25). Whatever traffic was blocked was

due to the fact that the last part of the line at one point

did not get across the street before a traffic light changed

(T. Vol. I, 56A). Again, no businesses were closed (T. Vol.

I, 59A) and any crowds that collected were kept moving

(T. Vol. I, 55A).

On December 17, 1961, a march occurred consisting of

about 266 persons. It was led by Dr. Anderson, Rev. Ralph

Abernathy and Dr. Martin Luther King. The police had

blocked traffic along the route of the march and they had

closed establishments serving alcoholic beverages. As

they marched, the group obeyed traffic signals. There were

remarks from persons assembled along the route of march

but not from the demonstrators. The Chief of Police testi

fied that everyone who was observing the march moved on

when requested to do so by his men. Again, there were no

incidents (T. Vol. I, 63A-71A, 225A).

On December 13, 1961, there was a kneel-in in front of

the City Hall. There were crowds of curious onlookers

across the street, but there was no commotion or dis

turbance of traffic. Pedestrian and vehicular traffic were

normal, with the exception of onlookers, and the police

had the situation under control throughout (T. Vol. II,

336A, 340A,—Def. Exh. 23 (q-v) ; Def. Exh. 24).

s

12

On July 21, 1962, a march involving about 61 people took

place (T. Vol. 1,132A). A crowd assembled as they marched

(T. Vol. I, 133A). The crowd became boisterous and mem

bers of the Albany Movement “were there policing their

own crowd” and with city policemen were successful in

keeping order (T. Vol. I, 136A-137A).

There was considerable testimony relative to a demon

stration involving about 40 people that occurred on the

night of July 24, 1962. After those who were in the line of

march were arrested, a large crowed estimated variously

from 2,000 to 4,000 persons gathered in the Negro area

and rocks and bottles were thrown at police officers and

jeers, epithets and insults hurled. However, none of the

testimony connected any of the persons in the line of march

or any of those named as defendants in the action with

engaging in or encouraging any of the violence that oc

curred on the part of the post demonstration crowd. In fact,

the testimony was that members of the Albany Movement

did everything they could to help control the crowd (T. Vol.

I, 137A-143A; Vol. II, 324A-347A).

4) Denial of Permits and Police Cooperation

The determination of the City of Albany to bar the pro

tests of the Albany Movement is seen in the manner in

which the city handled requests for a permit for a demon

stration made by Movement officials in attempts to comply

with the Albany parade ordinance. All requests were uni

formly denied and then arrests wTere made for parading

without a permit.

Responsibility for issuing permits rests with the City

Manager (T. Vol. IV, 836A). However, there are no stand

ards in the Albany City Code (Chapter 25, §35) which

define what constitutes a parade (T. Vol. I, 221A). There

isn’t any written policy guide under which the City Man-

13

ager determines when a permit will issue (T. Vol. IV,

836A-837A). There is no formal application blank which

must be completed in order to obtain a permit (T. Vol. IV,

841A-842A). Consequently, a parade is whatever the Chief

of Police construes to be a parade (T. Vol. IV, 221A-222A).

He does not construe four pickets in one block as constitut

ing a parade (T. Vol. I, 249A), nevertheless, on or about

June 24, 1962, four Negro residents of Albany were ar

rested for picketing in the 100 block of Washington Street

and charged with disobeying an officer and disorderly con

duct (T. Vol. II, 267A).

Requests are made informally by telephone or letter to

the City Manager or Chief of Police. When requests are

made to the City Manager, they are generally forwarded

to the Chief of Police for his advice. Oral requests for a

permit have been granted by these officials and they have

acted on these requests within the same day upon which

the request was received (T. Vol. IV, 847A-849A).

At a meeting in the Albany City Hall on July 13, 1962,

Dr. Anderson orally requested a permit to hold a prayer

service in front of the City Hall which request was denied

(T. Vol. IV, 902A-903A).

Shortly thereafter, a delegation of two or three persons

went to the City Manager to make a formal oral request

for a permit to hold the prayer meeting mentioned at the

July 13th meeting. The City Manager specified what in

formation should be included in a letter formally request

ing a permit: the route, the time, the approximate number

of persons involved, the sponsors, and the intention of the

gathering (T. Vol. IV, 850A-851A).

By letter dated July 19, 1962, Dr. Anderson on behalf

of the Albany Movement, wrote the City Manager and in

formed him that a prayer service would be held in front

14

of City Hall on July 21, 1962. The letter contained the

required information, asked the assistance of the Albany

Police Department in facilitating the crossing of the streets

by the group on their way to the City Hall, and stated that

the purpose of the gathering was to “manifest in the pres

ence of God, the Albany community, and the world our

great concern over the inability of Negro citizens of Albany

to effectively communicate to the city fathers their com

munity problems” (Pl. Exh. A; T. Vol. IV, 846A-852A;

866A-881A). This letter was considered as a threat to

violate the City parade ordinance (T. Vol. IV, 880A) rather

than a request for a permit; and instead of replying, the

City officials secured from Judge Elliot the restraining

order without notice referred to above, attaching a copy

of Dr. Anderson’s letter to their complaint. This consti

tuted the basis of the action in No. 20720.

Opinion and Order of June 28, 1963

Though hearing of all cases concluded on September 26,

1962, the District Court did not render any decision until

February 14, 1963 when it dismissed the suit for an injunc

tion requiring desegregation of the city’s public facilities.

This judgment was later reversed by this court in the first

Anderson case brought here.

The cases presently being appealed were not decided until

June 27, 1963, almost a year after they had been filed and

nine months after all proceedings had been concluded and

after this court in the earlier Anderson case had opined

that, in its view, the parties were entitled to a prompt deci

sion on their pending motions (321 F. 2d at 658).

In its decision of June 28, 1963, the District Court de

clined to rule upon appellees’ prayer made in the Kelley case

to dismiss the action on the ground of lack of jurisdiction,

feeling that it was unnecessary to determine this question

15

of jurisdiction since plaintiffs in Kelley had counterclaimed

in Anderson for essentially the same relief as prayed by

them in Kelley. The court’s view was that determination

of the question of jurisdiction would only have been neces

sary in the event the relief prayed in Kelley was granted

with respect to parties who were not also parties in Ander

son (R. Kelley 41; R. Anderson 32). Of course, since the

court had determined to deny relief to all parties, there

was no question of the granting of relief with respect to

persons who were parties in one case but not in the other.

The basis of the court’s denial of relief with respect to

both main claims and the counterclaim was that the events

detailed in the record had occurred many months before

litigation; and after the issuance of the temporary restrain

ing order in Kelley, the general community situation im

proved ; and with the exception of the date upon which the

temporary restraining order was dissolved by Judge Tuttle

of this court, no further unrest took place. The court also

noted that there had been no evidence of any substantial

incidents or aggravations that had occurred during the

period of the hearings (R. Kelley 42-43; R. Anderson 34).

Finally, the parties had not submitted any additional evi

dence of anything that had developed since September 26,

1962 (R. Kelley 44; R. Anderson 35). Consequently, neither

side in the court’s view was entitled to relief as of the

time the hearings concluded or the date of the opinion

(R. Kelley 45; R. Anderson 36).

Specification o f E rro rs

Because two appeals and a cross appeal are here in

volved, appellants-appellees in Anderson, No. 20,711 and

appellees in Kelley, 20,720, believe it would be helpful to

the court to specify those errors which they believe are and

are not involved in the three appeals as follows:

16

1. The court below erred in finding “as a matter of fact

and as a matter of law that the situation existing at the

time of the conclusion of the hearings in these matters and

the situation now existing insofar as the Court is informed

does not show on the part of W. G. Anderson and others,

as plaintiffs in Civil Action No. 731 (Anderson, 20,711),

such a denial to Negro citizens of the right to peacefully

protest and demonstrate against alleged State enforced

racial segregation or segregation in the other circum

stances complained of, nor such threats or intimidation as

would warrant the relief sought by them.”

2. The court below erred in refusing to enjoin arrests

for peaceful picketing of department and other stores in

the City of Albany since such arrests as demonstrated by

the uncontradicted testimony in the record violated rights

secured by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the

Federal Constitution.

3. The court below erred in refusing to enjoin arrests

for participating in prayer vigils in front of City Hall in

the City of Albany since such arrests as evidenced by the

uncontradicted testimony violated rights secured by the

First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Federal Constitu

tion.

4. The court below erred in refusing to enjoin arrests for

participating in peaceful anti-segregation protest demon

strations of the kind described in Dr. W. G. Anderson;s

letter to the City Manager of July 19, 1962 (R. Kelley 11)

and which Dr. Anderson and other parties attempted to

hold from November 1962 through July 1963, since such

demonstrations are clearly within the ambit of First and

Fourteenth Amendment guarantees.

5. The court below erred in refusing to hold the parade

ordinance of the City of Albany (Chap. 24, §35 of City Code

17

of Albany) unconstitutional on its face and as applied as

requested by appellants in Anderson, 20,711, in their pro

posed findings of fact and conclusions of law and as demon

strated by uncontradicted testimony of the City Manager.

6. The court below did not err in refusing to grant the

injunction requested by city officials in Kelley, 20,720, since

the complaint failed to state a federal cause of action upon

which relief could be granted and the record failed to prove

one.

7. The court below did not err in refusing the injunction

requested by city officials on their counterclaim in Anderson,

20,711, because the officials:

a) failed to prove that any appellant-appellee sought

to be enjoined wilfully or intentionally attempted to deprive

any other person of the equal protection of the laws.

b) failed to prove that any appellant-appellee sought to

be enjoined wilfully or intentionally attempted to prevent

any official from performing any duty imposed on such

official by state or federal law.

c) failed to prove that any appellant-appellee or any

person or persons associated with him actually advocated

or actually engaged in any violence.

d) failed to prove that any appellant-appellee or any

person associated with him violated any valid law of the

State of Georgia or any valid ordinance of the City of

Albany.

8. The court below did not err in refusing to grant the

injunction requested by city officials on their counterclaim

in Anderson, 20,711, because these officials were guilty of

enforcing unconstitutional racial segregation in both public

and private facilities, Anderson v. City of Albany, 321 F.

18

2d 649 (C. A. 5th 1963) against which the parties sought

to be enjoined were protesting and consequently came into

equity with unclean hands.

A R G U M E N T

I.

T he C ourt Below E rred in D enying A ppellants in

Anderson, No. 2 0 7 1 1 , th e In junctive R elief to W hich

T hey W ere E ntitled by th e Evidence.

A. No Abatement of Grounds for Equitable Relief

The court below denied all injunctive relief requested by

appellants in Anderson, No. 20711. This denial was pur

suant to what that court described as a finding “ . . . as a

matter of fact and as a matter of law that the situation

existing at the time of the conclusion of the hearings in

these matters and the situation now existing insofar as the

Court is informed does not show on the part of W. G.

Anderson and others,. . ., such a denial to Negro citizens of

the right to peacefully protest and demonstrate against

alleged State enforced racial segregation or segregation in

the other circumstances complained of, nor such threats or

intimidation as would warrant the relief sought by them”

(R. Anderson 36).

In other words, the court concluded, without any state

ment in the record to this effect, that the Albany city

policy have abandoned their policy of arresting persons

who peacefully picket department and other stores, hold

small prayer vigils in front of City Hall, and walk to City

Hall in large numbers in the manner described in Dr. An

derson’s letter to the City Manager of July 19, 1962 (R.

Kelly 11) and who otherwise peacefully demonstrate

against segregation. The court also obviously had con-

19

eluded, again without any record foundation, that the

grievances of the Negro community which generated these

demonstrations had been so far adjusted as to preclude the

“probability of resumption” * of peaceful protests and

more arrests. The record is to the contrary.

In November 1961, Negro citizens in Albany, Georgia

commenced public protest demonstrations against all segre

gated facilities open to the general public. During that

month, the Albany Movement, an unincorporated associa

tion of individuals, was born. It is still in existence. The

organization and the demonstrations were sparked by the

inability of Negro community leaders to negotiate griev

ances (Tr. Vol. 1,117A-119A). More specifically, the Albany

Movement leaders sought to have the city desegregate

public library and recreational facilities, the city’s audi

torium, and the city’s hospital facilities. Segregation in

all of these public facilities, except the hospital, has been

enjoined by the District Court pursuant to this court’s

decision in Anderson v. City of Albany, 321 F. 2d 649,

although the city’s parks remain closed as indicated on that

appeal and the main swimming pool has been sold. Arrests

for attempting to use these facilities lawfully on a non-

segregated basis likewise have been enjoined. The Move

ment’s objectives were also to end discrimination in the

selection of juries and public employment. The curbing

of police brutality was another goal.

The privately owned facilities which the Albany Move

ment sought to desegregate were public transportation

facilities (buses were required by local ordinance to be

segregated) including taxicabs (required by local ordi

nance to be segregated) and privately owned theatres

(also required by local ordinance to segregate ticket lines)

4 United States v. Oregon State Medical Society, 343 U. S. 326,

333.

20

drug and department stores open to the general public

(Tr. Vol. I, 107A-1Q9A). This court’s decision in Anderson

v. City of Albany, swpra, also has resulted in an injunction

against enforced racial segregation on public buses, in the

bus and train stations, in taxicabs and theatre ticket lines.

Arrests for attempting to lawfully use same on a lion-

segregated basis have been enjoined. Additionally, the

Movement sought to increase employment opportunities for

Negroes in private establishments.

In short, the objectives of the Albany Movement were,

and still are, the total elimination of racial discrimination

and segregation in facilities open to the general public.

However, these objectives are far from won. Hospital fa

cilities are still segregated, the theatres still have segre

gated seating arrangements, white taxicabs still refuse to

ride Negro passengers, the department stores and drug

stores are still segregated with respect to lunch counters

and rest room facilities. No progress has been made in

securing wider employment opportunities for Negroes in

either public or private employment. Police brutality and

jury discrimination are continuing unresolved problems.

During the course of the demonstrations, according to

the city officials, “the city made 1,100 cases (109A), in

volving about 450 people (147A).” (Consolidated Brief

Kelley 13.) These persons were charged with unlawfully

congregating on the sidewalks so as to obstruct same (Chap.

24, §36 City Code of Albany), parading without a permit

(Chap. 24, §35 City Code) willfully failing or refusing to

obey an officer (Chap. 11, §6 City Code) and disorderly

conduct (Chap. 14, §7 City Code).5 These arrests were

designed to and did accomplish a drastic reduction in dem

onstration activity. But the fact that the unlawful arrests

have accomplished their objective of breaking the back

6 These ordinances are set forth on pp. 34-35 of Consolidated

Brief in Kelley.

21

of the Albany Movement does not render the case moot or

provide a factor which might be taken into consideration

by the District Court in determining whether an injunc

tion against future arrests should issue. United States v.

W. T. Grant, 345 U. S. 629, 633.

Moreover, the record is clear that there were demon

strations in Albany after the commencement of this action

on July 24, 1962. On July 30, 1962, the Chief of Police

testified, at great length, regarding demonstrations which

had occurred prior to July 24th, 1962. Then the Chief was

asked by his attorney, the Mayor of the City of Albany,

whether there had been any demonstrations in Albany after

July 24th. The Mayor queried:

Q. Now, since the 24th, after that big demonstra

tion then, what has been taking place? A. They held

other press conferences there at the residence of Dr.

W. G-. Anderson.

Q. Have there been any other demonstrations or any

other activity supported by any of the Defendants?

A. There have been demonstrations and such at the

City Hall, in groups of 10, 9, or as high as 25 or 28.

Q. Did any of these people relate to you why they

were demonstrating? A. They were demonstrating

because the City Commission, in their own words,

“would not yield to their demands.”

Q. Did they assign any other reason for congregat

ing in front of the City Hall? A. Their statement to

me was that they were there to protest the activity of

the City Commission (Tr. Vol. I, 44A-45A).

In addition, the Chief of Police testified that he had been

advised that the Albany Movement intended to continue

demonstrations against segregation. Queried about this by

the Mayor, the Chief testified:

22

Q. Now, Chief Prichett, have you discussed the mat

ter of other activities of the Albany Movement with

any of these defendants recently? A. Yes, I have.

Q. What has been their attitude, Mr. Prichett? A.

Their attitude has been such that they felt, they said

they felt compelled—that they would not have any mass

demonstrations now, because of the people not being

willing to follow their non-violence; that they would

have only small groups, consisting of 10 and as high as

27, to come to the City Hall to pray; but they said they

would not—that they would continue their demonstra

tions in violation of our laws.

* # # # #

Q. Chief Prichett, after Dr. King was sentenced and

incarcerated did he state to you, after his fine was paid,

whether or not he wanted to stay in jail or be released?

A. He stayed (sic) he wanted to remain in jail.

* # # # #

Q. Did he at that time make any mention of the ordi

nances of the City? A. He did.

Q. What did he say? A. He stated there in my

office on his release that he would continue to fight this

struggle to do away with the evil system of segregation,

in his own words (Tr. Vol. I, pp. 146A-148A).

Again, as demonstrated above, segregation is far from a

moot issue in Albany, Georgia. The record here shows that

same “steelhard, inflexible, undeviating official policy of

segregation” of which this court took judicial notice in

United States v. City of Jackson, 318 F. 2d 1, 5-6. When

Negro citizens of Albany petitioned the city officials to

desegregate facilities over which they had control, the

Mayor acknowledged that the petitions had been considered

by the City Commissioners, but they had concluded that

there were “no areas of agreement” and the petitioners

23

should, therefore, “go to court” (Tr. Yol. IV, pp. 777A-

778A, 781A-783A). The record leaves no doubt that the

Mayor and other white people in Albany would rather see

the swimming pools closed than integrated (Tr. Vol. V,

pp. 64B-65B, 76B-77B). The parks have been closed and

the white swimming pool sold. The segregation ordinances

were not repealed until long after suit to enjoin enforce

ment of same was commenced. Anderson v. City of Al

bany, supra, at p. 657. And no desegregation in Albany

has occurred other than that ordered by this court; except

that the library was desegregated on a stand-up basis just

prior to the argument on appeal in Anderson v. City of

Albany, supra, at p. 656.

Clearly, then, this court’s words in Bailey v. Patterson,

323 F. 2d 201, 205 are controlling here:

Under these circumstances, the threat of continued

or resumed violations of appellant’s federally protected

rights remains actual. Denial of injunctive relief might

leave the appellees “free to return to [their] old ways.”

United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U. S. 629, 632,

73 S. Ct. 894, 897, 97 L. ed. 1303 (1953).

The refusal of the court below to grant any relief, under

the circumstance here, was patently unjustified and leaves

the city officials free to resort to arrests and charges of law

violations as the vehicles for suppression of future free

speech demonstrations against segregation.

B. The Record Discloses Plain Violations of

First Amendment Freedoms

1. The record is clear that appellants Anderson, Slater

King, Jackson and Harris were arrested and charged with

failing to obey an officer and disorderly conduct when they

peacefully picketed department stores in the 100 block of

North Washington Street in March 1962 (Tr. Vol. II,

24

266A-269A). Two of these appellants were on one side of

the street and two on the other carrying signs protesting

discrimination against Negroes. Other small groups of

pickets were similarly arrested (Tr. Vol. I, 246A, 249A-

251A-256A). Nowhere in their statement of the facts do

the city officials describe the Washington Street incident.

In the argument in their brief (Consolidated Brief Kelley,

pp. 41-42) the city officials say:

“The only evidence adduced by plaintiffs in this case

in support of their motion for preliminary injunction

against interference with their demonstrations and

picketing was to the effect that on one occasion in March,

1962, arrests were made of four of the plaintiffs be

cause of their picketing (149B).”

The circumstances surrounding these arrests the City

claims were disputed. In support of this contention, they

cite the testimony of the arresting officer, Summerford, who

testified that he arrived on the scene around 5:30 and re

mained until 6 o’clock. He claimed the pickets were caus

ing the streets to become congested because they attracted

a crowd (Tr. Yol. VI, 273B). When photographs of the

scene contradicted this, the officer declared that these pic

tures did not accurately depict the situation (Tr. Vol. VI,

279B-289B). But it is self-evident that two pickets on one

side of a city block and two pickets on the other would not

interfere with sidewalk traffic.

Bealizing the weakness of their position, the City then

argues that applicable here is the rule established in Milk

Wagon Drivers Unions v. Meadowmoor Dairies, 312 U. S.

287, that even peaceful picketing may be prohibited when

enmeshed with violence. However, the city officials do not

point to any violence which had occurred in the City of

Albany prior to March 1962 (Consolidated Brief Kelley,

pp. 6-8) or during the course of this picketing. Conse-

25

quently, there being no prior or contemporaneous violence,

there was no such serious violence as dictated the Meadow-

moor rule. According to the city officials’ own statement of

the facts in these cases, no violence occurred until the inci

dent of July 10, 1962 (Consolidated Brief Kelley, p. 8).

Then, someone, unidentified, threw rocks at a police car and

a vehicle occupied by an agent of the F.B.I. and a dome

light on one vehicle was broken. This was many months

after March 1962.

The picketing which took place in March 1962, the object

of which was the elimination of racial discrimination in de

partment stores open to the general public, including Ne

groes, was a clear, unadulterated exercise of the First

Amendment right of free speech protected against state

abridgment by arrest, and other interference, by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution. Edwards v.

South Carolina, 373 U. S. 229; Thornhill v. State of Ala

bama, 310 U. S. 88; American Federation of Labor v. Swing,

312 IT. S. 321; Bakery and Pastry Drivers & Helpers Local

v. Wohl, 315 U. S. 769; Cafeteria Employees Union v. An

gelos, 320 U. S. 293. “Picketing when not in numbers that

of themselves carry a threat of violence may be a lawful

means to a lawful end.” Hughes v. Superior Court of Cali

fornia, 339 U. S. 460, 466; New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary

Grocery Co., 303 U. S. 552. “Nor may a state enjoin peace

ful picketing merely because it may provoke violence in

others.” Milk Wagon Drivers Union v. Meadowmoor

Dairies, supra, at p. 296. Here there was no violence pro

voked by the picketing of department stores, yet the court

below refused the requested injunction against continued

denial of the right of the Negro citizens of Albany to peace

fully picket such establishments (R. Anderson, 3).

2. The testimony of the Chief of Police established that

there were demonstrations in front of City Hall in groups

26

of 2 and “in groups of 10, 9 or as high as 25 or 28” (Tr.

Vol. I, 144A, Vol. II, 274A, 282A). Upon direct examina

tion by the Mayor, the Chief was asked:

Q. Did any of these people relate to you why they

were demonstrating ? A. They were demonstrating be

cause the City Commission, in their own words “would

not yield to their demands” (Tr. Vol. I, p. 144A).

Prior to this, the Chief had testified that some of these

demonstrations occurred after July 24, 1962, the date of the

filing of this suit (Tr. Vol. I, p. 144A; Yol. II, 357A). It is

thus undisputed that after this suit was commenced there

were small demonstrations against segregation in front of

City Hall. There was no violence accompanying these pro

tests. These persons were also arrested (Tr. Vol. II, 274A-

280A).

The right of Negroes to protest against state imposed

racial segregation cannot be gainsaid. NAACP v. Alabama,

357 U. S. 449. The Albany Movement was an organized

protest against such segregation. Its methods of protest

were unique. NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415. Small

groups in addition to picketing prayed in front of City Hall.

Such protest demonstrations against segregation are like

wise within the First Amendment’s guarantees of free

speech, peaceable assembly, and the right to petition the

government for redress of grievances. Edwards v. South

Carolina; NAACP v. Button, supra; Garner v. Louisiana,

368 U. S. 157, concurring opinion of Justice Harlan; they

are protected against city abridgment by arrest by the

Fourteenth Amendment. Edwards v. South Carolina,

supra; Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44. Despite this,

the court below refused to enjoin such arrests.

3. On several occasions, December 12th, 13th and 17th,

1961, and July 10th, 11th, 21st and 24th, 1962, large num-

27

bers of Negro anti-segregation protest demonstrators

ranging from approximately 32 in number to 267 on De

cember 12, 1961, left a Negro church, in Albany and at

tempted to walk, two abreast, upon the sidewalk to the City

Hall a few blocks away (Tr. Vol. I, 49A, 67A, 124A, 187A-

188A, 258A). On the first occasion, the marchers reached

City Hall. They were stopped and asked if they had a

parade permit. When they failed to produce a permit, they

were ordered to disperse. Upon failure to do so, they were

arrested. Similar incidents occurred on the other dates.

The Chief of Police testified that on all of these occasions

the marchers blocked traffic and the sidewalks and walked

against the traffic lights (Tr. Yol. I, 42A-46A, 55A, 68A).

Dr. Anderson testified that traffic signals were observed and

the sidewalks were not blocked (Tr. Vol. IV, 895A-896A).

The District Court made no specific finding of fact re

garding whether the testimony of the Chief of Police or Dr.

Anderson was correct. But assuming that the testimony of

the Chief of Police was correct, the question remains

whether this blocking of traffic and disobeying traffic sig

nals presented such a clear and present danger to the peace

and safety of the citizens of Albany as to justify the Dis

trict Court in refusing to issue an injunction against ar

rests for these otherwise peaceful demonstrations against

segregation. The answer on this record is obvious. There

was no such clear and present danger as to justify abridg

ment of First Amendment rights by arrest. Edwards v.

South Carolina, supra.

The record shows that what the demonstrators intended

was to walk two abreast upon the sidewalks, observing all

traffic signals, and holding a one-hour meeting in front of

City Hall protesting segregation (E. Kelley 11). Appel

lants specifically prayed for an injunction enjoining the city

officials from “continuing to pursue a policy of denying to

Negro citizens the right to peacefully protest against state

enforced racial segregation in the City of Albany, Georgia,

by peacefully walking, two abreast, upon the public side

walks of the City of Albany, observing all traffic signs and

regulations, to the City Hall in the City of Albany, Georgia

and peacefully assembling in front of City Hall, and peace

fully speaking out against such segregation during a period

of not more than two hours during the day, when traffic to

and from places of business and employment is not at its

peak” (ft. Anderson 8). This injunction the District Court

refused to issue although the record is clear from Dr. An

derson’s testimony (Tr. Vol. IV, 895A-896A) and his letter

to the City Manager (It. Kelley 11) that this was the kind of

mass demonstration which the Albany Movement undertook

to hold.

City officials have strained hard to find in this record

such advocacy of violence, or threat of violence, or actual

serious violence accompanying these mass demonstrations

as would justify the arrests of the demonstrators, Feiner

v. New York, 340 U. S. 315. However, these officials have

wholly failed to sustain their burden of showing such ad

vocacy, actual or threat of violence, as would lead a court

of equity to deny appellants the relief against arrests for

peaceful protests which was sought, Edwards v. South

Carolina, supra; Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296;

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1.

In the first place, there was never any violence by any

appellant, any member of the Albany Movement, or any

onlookers directed against the white community. Secondly,

there was never any violence directed by the white com

munity against any appellant, any member of the Albany

Movement or any members of the Negro community.

Thirdly, the violence which did occur was directed only

against the police and occurred in each instance only after

29

the leaders of the Albany Movement or other demonstra

tors had been arrested for peacefully protesting against

segregation (Tr. Vol. I, 120A-121A, 123A-124A, 137A,

139A, 140A; Vol. II, 330A, 335A). Fourthly, the little vio

lence which did occur was perpetrated by onlookers, who no

one could identify, or by persons unconnected with the

demonstrations (Tr. Vol. I, 257A; Vol. II, 364A; Vol. Ill,

620A-624A) and who were so few they could not be appre

hended by the police, although virtually all available police

were on the scene plus reinforcements (Tr. Vol. I, 124A-

127A; Vol. II, 360A). The violence which the police claim

occurred is set forth in the City’s brief (Consolidated Brief,

Kelley, p. 11). There, it is stated: “One officer was hit by a

bottle (449A) a state patrolman was hit in the face by a

rock, breaking two teeth (510A-524A); a newspaper re

porter was hit (472A); another officer had a bottle splatter

over his feet (618A) ; another had to duck to avoid being hit

(545A); and another was hit on the leg (536A). One of the

motorcycles was hit with a rock (691A).” At no time was

there such disorder that the police proved inadequate to

preserve law and order (Tr. Vol. I, 194A, 203A-206A,

226A-227A).

It is undisputed that the leaders of the Albany Movement

advocate non-violence as the only means for achieving de

segregation (Tr. Vol. I, 92A, 94A, 95A; Vol. Ill, 638A).

Moreover, the record shows that the Albany Movement

conducted clinics to instruct persons in the art of non

violence (Tr. Vol. Ill, 671A-672A) and aided the police

in restoring order when violence erupted (Tr. Vol. I, 94A-

95A, 136A-137A, 142A; Vol. II, 330A-331A, 333A). Fur

ther, when violence did occur on July 24, 1963, the follow

ing day Dr. King called for a Day of Penance (Tr. Vol. I,

145A). Consequently, Dr. King not only advocated non

violence and taught its methods but publicly condemned

those who engaged in violence. The record is clear that

30

there was no violence in the City of Albany after this Day

of Penance on July 25, 1962 and until the hearings below

ended on September 26, 1962. Despite this, however, the

District Court refused to issue an injunction as prayed

enjoining the police from arresting Dr. King and the others

who lead the marches to City Hall.

Certainly, the constitutional rights of these Negro lead

ers cannot be denied simply because violence by others

might accompany their exercise. Cf. Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U. S. 1; Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60. In Congress of

Racial Equality v. Douglas, 318 F. 2d 95, this Court held

that: “These fundamental rights to speak, assemble, seek

redress of grievances and demonstrate peacefully in pur

suance thereto cannot be abridged merely because a riot

might be threatened to be staged or that the police officers

are afraid that breaches of the peace will occur if these

rights are exercised” (at 102). See also, Hague v. C. I. 0.,

307 H. S. 496. These marches which Dr. King and Dr.

Anderson led were similar to the march of 187 Negro high

school and college students in Columbia, South Carolina

which the Supreme Court held in Edwards v. South Caro

lina, 372 XJ. S. 229; Fields v. South Carolina, 375 TJ. S. 44,

to be an exercise of the right of free speech, the right of

peaceable assembly, and the right to petition the govern

ment for a redress of grievances and protected against ar

rest by the state by the Fourteenth Amendment. It was,

therefore, plain error for the court below to refuse to en

join future arrests for peaceful mass demonstrations of

the kind pursued by the Albany Movement.

4. The arrests of Dr. King, Dr. Anderson and others

who participated in these marches were on charges of vio

lating the parade ordinance of the City of Albany (Tr.

Vol. I, 43A, 53A-55A, 63A-67A). This ordinance (Consoli

dated Brief Kelley, p. 34) provides: “All parades, demon-

31

strations or public addresses on the streets are hereby

prohibited, except with the written consent of the City Man

ager (Ch. 24, §35 of the City Code).” The ordinance, on

its face, places a total prohibition on all parades, demon

strations or public addresses except with the written con

sent of the City Manager. The ordinance, on its face, con

tains no guides for the discretion of the City Manager in

granting or withholding his consent. In addition, the City

Manager testified that he had no written policy guide (Tr.

Yol. IV, 837A). There was not even a written application

form for such consent (Tr. Yol. IV, 841A-842A). In short,

consent of the City Manager was vested in his sole discre

tion.

The city officials assert that there was no attack made

upon the validity of this ordinance which they claimed in

their suit, Kelley 20720, had been violated. Such assertion

overlooks two facts. First, in their answer the defendants

in the Kelley case denied that they had violated any “valid”

ordinance of the City of Albany (R. Kelley, 29-30). Second,

at the conclusion of the hearings in these cases the court

below requested the parties to submit additional briefs or

arguments. Appellants in Anderson, 20711, submitted pro

posed findings of fact and conclusions of law in which they

requested the court below to find as a fact that:

“Defendant, Stephen Roos, in his capacity as City

Manager of the City of Albany has authority under the

Albany City Code to issue permits for the holding of

parades and demonstrations in Albany (R. 727,

p. 1002). However there are no standards in the Al

bany City Code which define what constitutes a parade

(R. 727, p. 275) nor is there any written policy guide

under which the City Manager determines when a per

mit will issue (R. 727, pp. 1002-1003). There is not

even a formal application blank which must be filled

32

out in order to obtain a parade permit (R. 727, pp.

1008-1009). Consequently, a parade is whatever the

Chief of Police, in his opinion, construes to be a parade

(R. 727, pp. 275-76). He does not construe four pickets

in one block as constituting a parade (R. 727, p. 306).

Nevertheless on or about June 24, 1962, four Negro

residents of Albany were arrested for picketing in

the 100 block of Washington Street and charged with

parading without a permit (R. 727, pp. 306-308).”

The court below was also asked to conclude as a matter of

law that:

“A City Ordinance Requiring Application To An Official

As A Prerequisite For Obtaining A Permit For A Pub

lic Parade Or Assembly But Which Contains No Stand

ard Of Official Action But Rather Allows Refusal Of A

Permit On The Mere Opinion Of An Official That Such

Refusal Will Prevent Riots, Disturbances Or Disord

erly Assemblages Is Unconstitutional. Hague v. C. I. O.,

307 U. S. 496.”

There is no question that Albany’s parade ordinance is

unconstitutional on its face. Hague v. Committee of Indus

trial Organizations, 307 U. S. 496; Staub v. Baxley, 355

IT. S. 313. That ordinance, on its face, imposes an uncon

stitutional prior restraint upon the enjoyment of First

Amendment freedoms. Staub v. Baxley, supra. Notwith

standing the surface unconstitutionality of this ordinance,

the court below refused to issue an injunction enjoining

arrests for walking to the City Hall as requested (R. Ander

son 8-9).

In addition to arresting demonstrators for allegedly vio

lating the parade ordinance, the police officers also ar

rested for disorderly conduct, willfully refusing to comply

with the lawful order of a police officer, and congregating

33

on the sidewalk so as to obstruct same, as provided by other

ordinances of the City of Albany (Consolidated Brief

Kelley, pp. 34-35). These ordinances were not attacked

below as unconstitutional on their face. In their answer the

defendants in Kelley alleged “that the Chief of Police and

other police officers of said city have sought in various and

divers ways to thwart the peaceful attempts of said defend

ants and others exercising their constitutional rights of

freedom of assembly and of peaceful protest, by arresting,

harassing and intimidating the defendants and others en

gaged with them . . . ” (E. Kelley 30). The complaint in

Anderson, 20711, was directed in its entirety to enjoining

such arrests in the future.

Clearly, free speech, free assembly, and freedom to peti

tion for redress of grievances cannot be denied to Albany

Negroes “under the guise of constitutionally worded stat

utes and ordinances” invoked in the name of preserving the

public peace and safety. Edwards v. South Carolina, supra;

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44; Cantwell v. Con

necticut, 310 U. S. 296; Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1.

“The circumstances in this case reflect an exercise of

these basic constitutional rights in their most pristine and

classic form.” Edwards v. South Carolina, supra at p. 235.

Here, as in Edwards, the demonstrators “were peaceably

expressing” opinions “sufficiently opposed to the views of

the majority of the community to attract a crowd and

necessitate police protection” (at p. 237). The Supreme

Court’s holding in the Edwards case is plainly apposite

here:

“The Fourteenth Amendment does not permit a state

to make criminal the peaceful expression of unpopular

views. ‘[A] function of free speech under our system

of government is to invite dispute. It may indeed best

serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of

34

unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they

are, or even stirs people to anger. Speech is often

provocative and challenging. It may strike at preju

dices and preconceptions and have profound unsettling

effects as it presses for acceptance of an idea” (at

p. 237).

Unmoved by these great constitutional principles, the

court below refused to enjoin the thwarting of peaceful

protest demonstrations by arrests “under the guise of con

stitutionally worded statutes.”

II.

The C ourt Below D id N ot E rr in R efusing to G rant

th e In ju n c tio n R equested by City Officials in Kelley,

2 0 ,7 2 0 .

Albany city officials have appealed from the refusal

below to grant a permanent injunction against individual

Negro leaders of the Albany Movement and the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the

Congress of Racial Equality, the Southern Christian Lead

ership Conference and the Student Non-Violent Coordinat

ing Committee enjoining these individuals and organiza

tions from:

“continuing to sponsor, finance, incite or encourage

unlawful picketing, parading or marching in the City

of Albany, from engaging or participating in any un

lawful congregating or marching in the streets or

other public ways in the City of Albany, Georgia; or

from doing any other act designed to provoke

breaches of the peace or from doing any act in viola

tion of the ordinances and laws hereinbefore referred

to” (R, Kelley, 10).

35

Such, an injunction was granted on July 20, 1962, without

notice or hearing, returnable 9 days later. Attached to

the complaint for such injunction was a letter which Dr.

W. G-. Anderson, president of the Albany Movement, had

written to the City Manager on July 19, 1962 requesting

police cooperation in a proposed prayer vigil in front of

City Hall (R. Kelley, 11). This letter was construed as a

threat to violate the parade ordinance of the City of

Alban} .̂ On July 24th the injunction was vacated, pend

ing a hearing, by Chief Judge Tuttle of this court on the

ground that the court below was clearly without jurisdic

tion to entertain the case. Jurisdiction below had been

predicated on Title 28, U. S. C. A., §§1331 and 1343(3).

The complaint alleged that the action was brought “to

vindicate . . . rights conferred by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States and 42

U. S. C. A., §1985(3)” (R. Kelley, 2).

The alleged federal rights sought to be vindicated were

those of citizens and inhabitants of Albany “to the free

and equal use of the streets, sidewalks and other public

places in and about the City of Albany; to secure to said

citizens and inhabitants equal protection of the laws as

guaranteed to them by the Constitution of the United

States; and to secure to said citizens and inhabitants the

free and uninterrupted use of their respective private

property, free from organized mass breaches of the peace

which tend to prevent and hinder plaintiffs and other duly

constituted authorities from according to said citizens and

inhabitants the equal protection and due process of law”

(R. Kelley, 1-2).

After the injunction order of July 20th was vacated,

the action came on for hearing on July 30th at which time

the defendants moved to dismiss the action for lack of

jurisdiction (Tr. Vol. I, p. 1A). The court below ruled as

follows:

36

“I rule that the Court does have jurisdiction and I

overrule the motion to dismiss and the plaintiffs may

proceed” (Tr. Vol. I, p. 1A).

In its opinion of June 28, 1963, however, that court ruled

that since the city officials had filed a counterclaim in an

action brought by the leaders of the Albany Movement to

enjoin arrests for peaceful picketing in which the city

officials alleged substantially the same facts and sought the

same relief as was sought in this action, it was unneces

sary to determine the question of jurisdiction, unless the

relief prayed for was granted with respect to denominated

parties in this action who are not denominated parties in

the Albany Movement leaders’ action. The defendant in

dividuals and organizations did not appeal from the judg

ment below denying the city’s request for a permanent

injunction similar to the one vacated by Judge Tuttle.

However, the court below did not err in refusing to grant

the requested permanent injunction. This court held in

Congress of Racial Equality v. Clemmons, 323 F. 2d 54, a

similar case brought by officials of Baton Rouge, Louisiana,

that the District Court could not proceed to hear and de

termine a complaint alleging facts similar to those alleged in

this complaint and invoking the identical jurisdictional pro

visions. The court ruled the facts there alleged attempted

to state a federally granted right based on Title 28, U. S.

C. A., §1343(3) and Title 42 U. S. C. A., §1985(3) but failed

to do so since the complaint and the evidence did not show

a cause of action arising under the Constitution and laws of

the United States. Here, as in the Clemmons ease, “there

is nothing in the complaint and nothing in the record to show

purpose on the part of the defendants to deprive anyone

of equal protection of the laws. On the contrary, the whole

object of the demonstration was to secure equal protection

of the laws for all. At most, the plaintiffs alleged and

37

proved that the defendants blocked traffic (for a short

while) and that the . . . officials called a large number of

police to the Courthouse, reducing police protection in other

parts of the City” (at p. 60).

This case, as the Clemmons case, is fatally defective be

cause the plaintiff city officials were deprived of no federal

rights. “Blocked traffic inconvenienced some citizens, re

duced police protection was a hazard to some citizens, but

this does not mean that the rights adversely affected were

federal rights” (at p. 61).

Again, as in the Clemmons case, the third fatal weakness

is that the defendants here as there are private persons. “It

is still the law that the Fourteenth Amendment and the

statutes enacted pursuant to it, including 42 U. S. C. A.,

§1985, apply only when there is state action” (at p. 62).

Consequently, the court below did not err in refusing to

reinstate the injunction which had been vacated by Chief

Judge Tuttle.

III.

The C ourt Below Did Not E rr in R efusing the In ju n c

tion R equested by City Officials on T heir C ounterclaim

in Anderson, 20 ,711 .

Albany officials sought to save their proposed cause of

action in Kelley by filing same as a counterclaim in the