Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush Brief in Opposition to Petitioners' Motion for Leave

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1956

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush Brief in Opposition to Petitioners' Motion for Leave, 1956. 210af163-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/05b473a1-9ae1-4fb0-a186-4848ae7df458/orleans-parish-school-board-v-bush-brief-in-opposition-to-petitioners-motion-for-leave. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

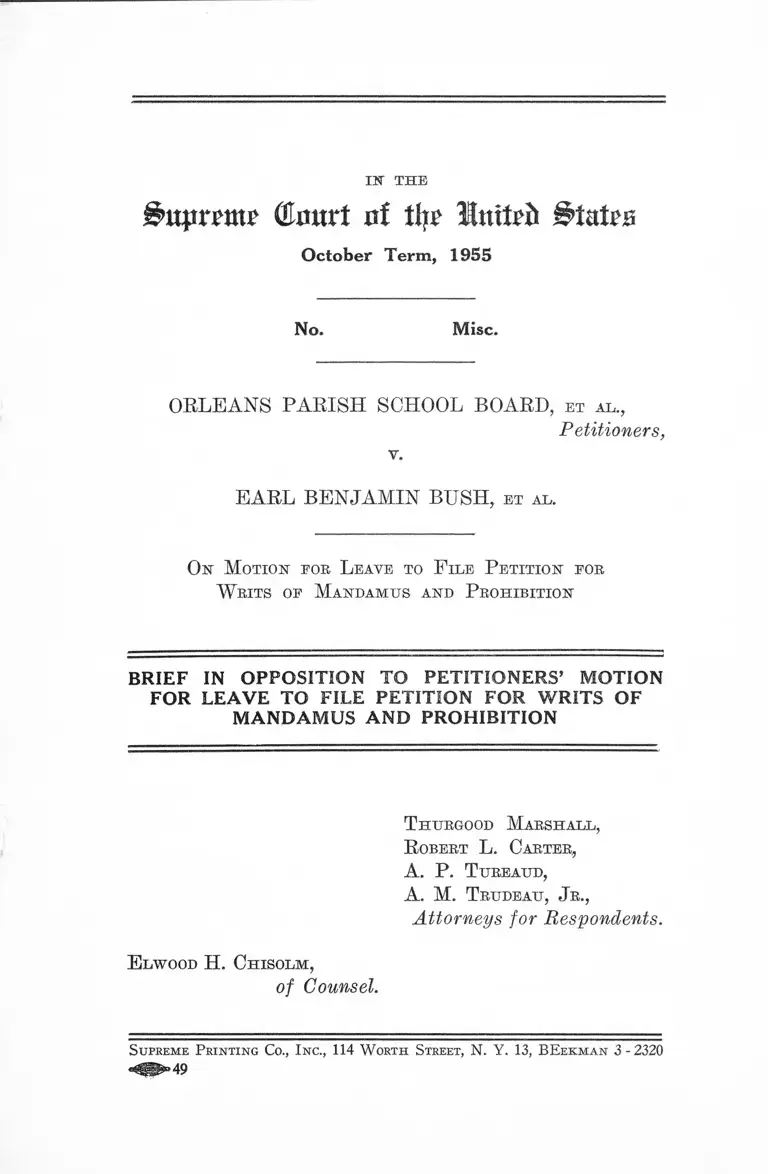

(tort nt tluv Imtrii States

October Term, 1955

IK THE

No. Misc.

ORLEANS PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, e t a l .,

Petitioners,

v.

EARL BENJAMIN BUSH, et al .

O n M otion fob L eave to F ile P etition fob

W rits of M andam us and P rohibition

BRIEF IN O PPO SITIO N TO PE TITIO N E R S’ M O TIO N

FOR L E A V E T O FILE PE TITIO N FO R W R IT S OF

M A N D A M U S A N D PROHIBITION

T hurgood M arshall ,

R obert L . Carter,

A . P . T ureaud,

A . M . T rudeau , Jr.,

Attorneys for Respondents.

E lwood H. C h iso lm ,

of Counsel.

Supreme P rinting Co., Inc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BE ekm an 3 - 2320

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions B e lo w ........................................................ 1

Question Presented......................................................... 2

Statement of the C a se ......................... .. 2

Argument ........................................................................ 4

Cases Cited

Banks v. Izzard, Civil Action No. 1236 (W. D. Ark.,

decided Jan. 18, 1956) unreported......................... 6

Bell v. Rippy, 133 F. Supp. 811 (N. D. Tex. 1955) .. 6

Brown v. Rippy, No. 15872 (CA 5th) ....................... 6, 7

California Water Service v. Redding, 304 II. S. 252 4

Case v. Bowles, 327 U. S. 9 2 ........................................ 4

Covington v. Edwards, Civil Action No. 323-R (M. D.

N. C., decided Apr. 6, 1956) unreported.................. 6

Dunn v. Board of Education, Civil Action No. 1693

(S. D. W. Va., decided Oct. 10, 1955) unreported . . 6

Ex parte Bransford, 310 U. S. 354 ............................. 4

Ex parte Buder, 271 IT. S. 4 6 1 ..................................... 4

Ex parte Collins, 277 U. S. 565 ..................................... 6

Ex parte Poresky, 290 IT. S. 3 0 ............................. .. 4

McKinney v. Blankenship, — Tex. —, 282 S. W. 2d

691 (1955) .................................................................... 6

Mathews v. Launius, 134 F. Supp. 684 (W. D. Ark.

1955) ............................................................................ 6

Phillips v. United States, 312 U. S. 246 ..................... 4, 6

School Segregation Cases (Brown v. Board of Edu

cation of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483; Id., 349 U. S.

294 .................................................................................. 3, 5

Willis v. Walker, 136 F. Supp. 181 (W. D. Ky. 1955),

136 F. Supp. 1 7 7 ......................................................... 5

11

Statutes Cited

PAGE

Constitution of the United States:

Fourteenth Amendment ....................................... 2

Federal Civil Rights A cts:

Title 42 U. S. C. §§1981, 1983 ............................. 2

Title 28 U. S. C. § 2281 ......................................... 4, 6

IN THE

gnutmtu' (tart of tip llnltih 0tata

October Term, 1955

No. Misc.

• o

Orleans P arish S chool B oard, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

E arl B e n ja m in B u sh , et al.

O n M otion for L eave to F ile P etition for

W rits of M andamus and P rohibition

-------------------------------------- o ----------------------------------—

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITIONERS’ MOTION

FOR LEAVE TO FILE PETITION FOR WRITS OF

MANDAMUS AND PROHIBITION

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States District Court, entered

February 15, 1956, declaring the statutes unconstitutional

and dissolving the specially constituted three-judge District

Court which heard this case is reported in 138 F. Supp.

336. The opinion of the United States District Court,

also entered February 15, 1956, which denied petitioners’

motions to dismiss and granted a temporary injunction

against them is reported in 138 F. Supp. 337.

2

Question Presented

The sole question presented in this proceeding is

whether, in a case brought on behalf of minor Negro chil

dren to obtain admission to public schools on a nonsegre-

gated basis and where both declaratory and injunctive relief

are sought on the ground that state legislation is repugnant

to the Federal Civil Eights Acts as well as the Constitution

of the United States, it is procedurally proper for a statu

tory three-judge District Court to hear the cause and, sub

sequently, after determining that no serious constitutional

question is presented since the challenged legislation was

clearly unconstitutional, to withdraw from the case and

refer further proceedings to a one-judge District Court

which forthwith denies petitioners preliminary motions and

grants a temporary injunction.

Statement of the Case

Petitioners’ statement of facts cannot be accepted as-

entirely accurate or complete. Moreover, their statement

includes conclusions of ultimate fact rather than the bare

evidential facts. For these reasons, we consider it neces

sary to set forth the facts with greater particularity.

This suit was brought in behalf of minor Negro children

by their parents, guardians or next friends to obtain admis

sion to public schools of Orleans Parish on a nonsegregated

basis. The complaint was based on two grounds: First,

that certain state statutes and provisions of the Louisiana

Constitution which require or permit racial segregation in

public schools are repugnant to the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States. Second, that the

enforcement of these state statutes and constitutional pro

visions against plaintiffs violates their rights guaranteed,

under the Federal Civil Eights Acts, Title 42 U. S. C.

§§ 1981, 1983. A declaratory judgment plus temporary and

8

permanent injunctive relief against defendants, petitioners

here, were sought; and a statutory three-judge District

Court was requested.

Plaintiffs’ application for a temporary injunction and

petitioners’ motions to dismiss were heard before the statu

tory three-judge District Court on December 2, 1955.

Two and a half months later, on February 15, 1956, in a

per curiam opinion, the statutory District Court determined

that the challenged state statutes and constitutional provi

sion were invalid under this Court’s rulings in the School

Segregation Cases (Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka,

347 U. S. 483, 495; Id., 349 U. S. 294, 298); that no serious

constitutional question, not heretofore decided by this Court,

was presented; and that, accordingly, a statutory court was

not required. The statutory court then directed two of its

judges to withdraw and referred the case back to the single

judge District Court where it had been originally filed.

Subsequently, the latter court, also on February 15,

issued an opinion which disposed of petitioners ’ preliminary

motions to dismiss plus plaintiffs’ application for temporary

injunction; and, this was accompanied with an order which

restrained petitioners from “ requiring and permiting seg

regation of races in any school under their supervision,

from and after such time as may be necessary to such

schools on a racially nondiscriminatory basis with all de

liberate speed as required by the decision of the Supreme

Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, supra.”

Petitioners filed applications for rehearing or new trial

on February 24, 1956. Both the three-judge District Court

and the single-judge District Court denied the applications

submitted to them on March 8.

4

Argument

Section 2281, Title 28 U. S. C., clearly provides that a

three-judge District Court must be convened to hear an

application for an injunction against a state officer to

restrain the enforcement, operation or execution of a

state statute where the injunction is sought “ upon the

ground of the unconstitutionality of such statute.” How

ever, it is equally clear that a three-judge court is un

necessary unless the claim of unconstitutionality or the

question of constitutionality is “ substantial.” Ex parte

Foresky, 290 U. S. 30, 31; Ex parte Buder, 271 U. S. 461,

467. Similarly, it appears that no substantial constitu

tional question is presented when previous decisions of

this Court have foreclosed the issue. California Water

Service v. Redding, 304 U. S. 252, 255; E x parte Foresky,

supra, at p. 32. Moreover, where a state statute is attacked

on the ground that it violates a federal statute, the provi

sions for a three-judge court are inapplicable. Case v.

Bowles, 327 U. S. 92, 97; and this Court has denied a motion

for leave to file a petition for a writ of mandamus to

compel the convening of a three-judge court in a case

where the claim of unconstitutionality was obviously with

out merit yet a question of repugnancy to a federal law

was apparently substantial. Ex parte Bransford, 310 U. S.

354. Cf. Phillips v. United States, 312 U. S. 246; Ex parte

Buder, supra.

Turning to the instant case, the facts show that the com

plainants sought temporary and permanent injunctive re

lief plus a declaratory judgment against state oflicers to

restrain the enforcement of state statutes which required

or permitted racially segregated schools. The legislation

was assailed upon grounds of unconstitutionality and re

pugnance to the Federal Civil Rights Acts. A three-judge

court was convened. After examining the pleadings and

hearing the motions to dismiss and the application for

5

temporary injunction, it decided that the challenged stat

utes were unconstitutional, then withdrew and returned

the case to a single-judge court. In support of this the

three judges referred to the decisions of this Court in the

School Segregation Cases and concluded, at 138 F. Supp.

337:

In so far as the provisions of the Louisiana Con

stitution and statutes in suit require or permit

segregation of the races in public schools, they are

invalid under Brown.

* #• #

It now appears that no serious constitutional ques

tion, not heretofore decided by the Supreme Court

of the United States, is presented. Accordingly, a

three-judge court under 28 U. S. C. § 2281 is not

required.

Thereafter, the single-judge District Court issued a

temporary injunction, see Statement of the Case, supra,

after disposing of five defenses raised by petitioners in

their motions to dismiss. 138 F. Supp. 337. We submit

that this procedure was in full conformity with Section

2281 and fully satisfies its requirements.

While it is true that this Court has yet to squarely

approve the manner in which the court below proceeded,

it is significant to note that never before have so many

state officials in so many states persisted in enforcing

state laws which have been held unconstitutional by this

Court. It is also important to indicate that other District

Courts faced with like suits against recalcitrant school

authorities have convened as a three-judge court only to

withdraw and remand to a one-judge court which proceeded

to issue an injunction. See e.g., Willis v. Walker, 136 F.

Supp. 181 (W. D. Ky. 1955), 136 F. Supp. 177. In a number

of other cases where Neg'ro children have sought, or are

seeking, admission to public schools on a nonsegregated

basis, the single judge has presided throughout the pro

6

ceedings although three-judges were requested pursuant

to 28 U. S. C. 2281. See e.g., Bell v. Rippy, 133 F. Supp.

811 (N. D. Tex. 1955)/ appeal pending sub nom Brown

v. Rippy, No. 15872 (CA 5th); Mathews v. Launius, 134

F. Supp. 684 (W. D. Ark. 1955); Dunn v. Board of Educa

tion, Civil Action No. 1693 (S. D. W. Va., decided Oct.

10, 1955) unreported; Banks v. Iszard, Civil Action No.

1236 (W. D. Ark., decided Jan. 18, 1956) unreported; Cov

ington v. Edwards, Civil Action No. 323-R (M. D. N. C.,

decided Apr. 6, 1956) unreported. Thus, it appears that

District Courts in the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Eighth Cir

cuits, whether or not a three-judge court was preliminary

convened, have decided that a statutory court is not re

quired in this type of case.

Practical consideration would seem to favor a determina

tion that cases of this character do not require a three-judge

court. For, undoubtedly, it would impose a weighty and

unwarranted burden upon the federal judiciary and the

appellate docket of this Court to require a three-judge

court to be convened every time a Negro pupil seeks an

injunction against state officials who continue to enforce

an obviously unconstitutional state statute which requires

or permits racial segregation in public schools. Moreover,

such a requirement would seem to defeat the purposes

which Congress sought to achieve. Support for these con

siderations is found in a long line of cases, including Phillips

v. United States, supra; Ex parte Collins, 277 U. S. 565'.

Here, however, the Court below, faced with the clear re

quirements of Section 2281, sought to comply with its terms.

We submit that there were no procedural imperfections in

its action.

This Court in the Brown case, having decided that racial

discrimination in public education is unconstitutional, held

1 Decided September 16, 1956, about a month prior to the decision

of the State Supreme Court in McKinney v. Blankenship, — Tex.

— , 282 S. W . 2d 691 (1955).

7

that: “ All provisions of federal, state or local law re

quiring or permitting such discrimination must yield to

this principle.” In the face of this clear-cut decision peti

tioners, nevertheless, sought in the District Court and now

seek in this Court an opportunity to re-argue the merits

of the Brown decision. Obviously, such re-argument is

alien in either court.

These considerations, we submit, firm up into a con

clusion that the procedure adopted by the statutory Dis

trict Court in the instant case was a logical and proper

one: to determine whether the challenged statutes were

within the scope of the decision in the Brown case and,

upon reaching a determination that said statutes “ are

invalid under the ruling of the Supreme Court in Brown” ,

to then remand the case to a single judge to enforce the

remedial provisions of the Brown case.

W herefore, fo r the reasons h erein before stated, it is

resp ectfu lly subm itted the m otion fo r leave to fo r w rits

o f m andam us and p roh ib ition should be denied w ith

app rop ria te d irections.

T hurgood M arshall ,

R obert L. Carter,

A. P. T ureatjd,

A. M. T rudeau , J r .,

Attorneys for Respondents.

E lwood H . C h iso lm ,

of Counsel.