Statement by Jack Greenberg to the Press at New Orleans, LA., September 27, 1962 at 1:00 P.M. C.S.T

Press Release

September 27, 1962

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Statement by Jack Greenberg to the Press at New Orleans, LA., September 27, 1962 at 1:00 P.M. C.S.T, 1962. a2a20524-bd92-ee11-be37-6045bddb811f. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/05cc635b-d0a1-4d61-87a2-26d47eed036b/statement-by-jack-greenberg-to-the-press-at-new-orleans-la-september-27-1962-at-100-pm-cst. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

“

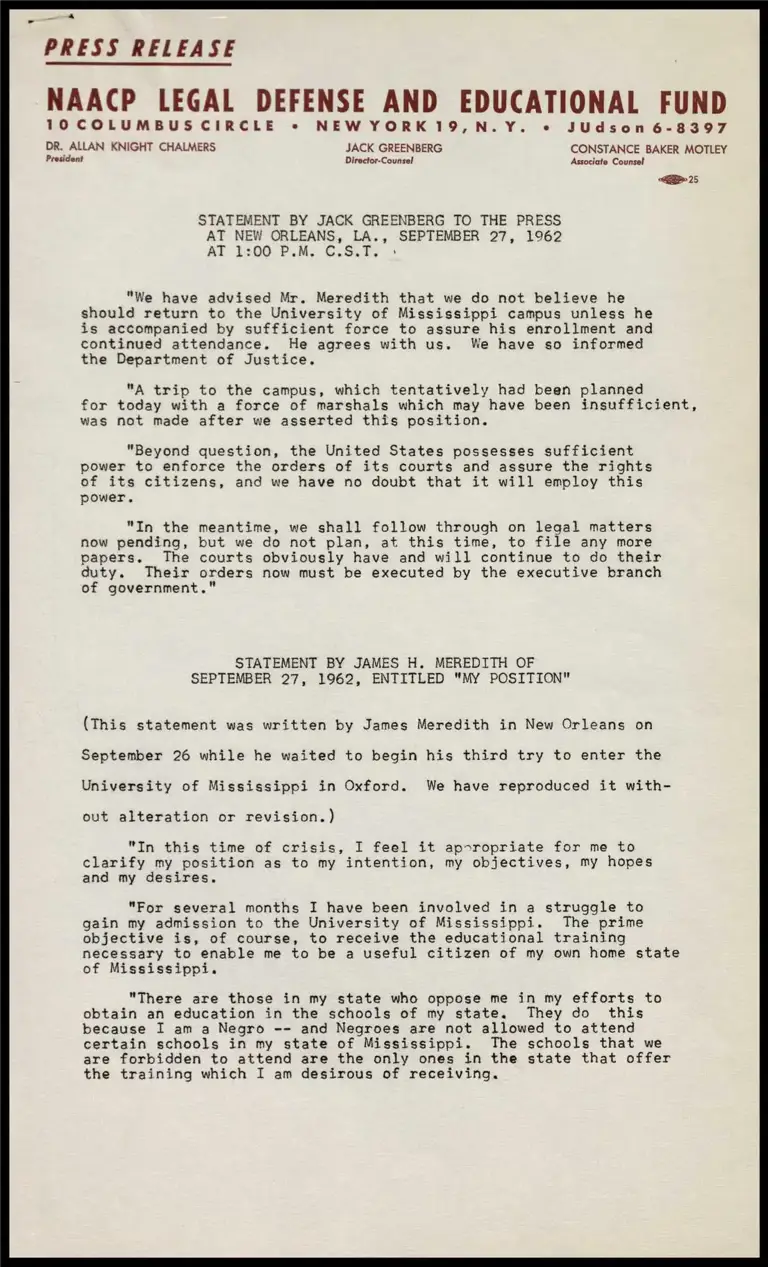

PRESS RELEASE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

TOCOLUMBUS CIRCLE + NEWYORK19,N.Y. © JUdson 6-8397

DR. ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS JACK GREENBERG CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY

President Director-Counsol Associate Counsel

S25

STATEMENT BY JACK GREENBERG TO THE PRESS

AT NEW ORLEANS, LA., SEPTEMBER 27, 1962

AT 1:00 P.M. C.S.T. +

"We have advised Mr. Meredith that we do not believe he

should return to the University of Mississippi campus unless he

is accompanied by sufficient force to assure his enrollment and

continued attendance. He agrees with us. We have so informed

the Department of Justice.

"A trip to the campus, which tentatively had been planned

for today with a force of marshals which may have been insufficient,

was not made after we asserted this position.

"Beyond question, the United States possesses sufficient

power to enforce the orders of its courts and assure the rights

of its citizens, and we have no doubt that it will employ this

power.

"In the meantime, we shall follow through on legal matters

now pending, but we do not plan, at this time, to file any more

papers. The courts obviously have and will continue to do their

duty. Their orders now must be executed by the executive branch

of government."

STATEMENT BY JAMES H. MEREDITH OF

SEPTEMBER 27, 1962, ENTITLED "MY POSITION"

(This statement was written by James Meredith in New Orleans on

September 26 while he waited to begin his third try to enter the

University of Mississippi in Oxford. We have reproduced it with-

out alteration or revision.)

"In this time of crisis, I feel it ap>ropriate for me to

clarify my position as to my intention, my objectives, my hopes

and my desires,

"For several months I have been involved in a struggle to

gain my admission to the University of Mississippi. The prime

objective is, of course, to receive the educational training

necessary to enable me to be a useful citizen of my own home state

of Mississippi.

"There are those in my state who oppose me in my efforts to

obtain an education in the schools of my state. They do this

because I am a Negro -- and Negroes are not allowed to attend

certain schools in my state of Mississippi. The schools that we

are forbidden to attend are the only ones in the state that offer

the training which I am desirous of receiving.

=O=

"Consequently, those who oppose me ave saying to me, we

have given you what we want you to have and you can have no more.

Except, maybe, they say to me, if you want more than we have

given you, then go to some other state or some other country and

get your training.

"Pray tell me what logic concludes that a citizen of one

state of the United States must be required to go to anothe state

to receive the educational training that is normally and ordinarily

offered and received by other citizens of that state. Further,

what justification can possibly justify one state assuming or

accepting the responsibility of educating the citizens of another

pee the training is offered to other citizens of the home

state

"We have a dilemma. It is a matter of fact that the Negroes

of Mississippi are effectively NOT first-class citizens. I feel

that every citizen should be a first-class citizen and should be

allowed to develop his talents on a free, equal and competitive

basis. I think this is fair and that it infringes on the rights

and privileges of no one.

"Certainly to be denied this opportunity is a violation of

my rights as a citizen of the United States and the state of

Mississippi.

"The future of the United States of America, the future of

the South, the future of Mississippi, and the future of the Negro,

rests on the decision -- the effective decision -- of whether or

not the Negro citizen is to be allowed to receive an education in

his own state.

"If a state is permitted to arbitrarily deny any right that is

so basic to the American way of life to any citizen, then democracy

is a failure.

"I dream of the day when Negroes in Mississippi can live in

decency and respect of the first order and do so without fear of

intimidation, bodily harm or of receiving personal embarrassment,

and with an assurance of equal justice under the law.

"The price of progress is indeed high, but the price of

holding it back is much higher."

ean