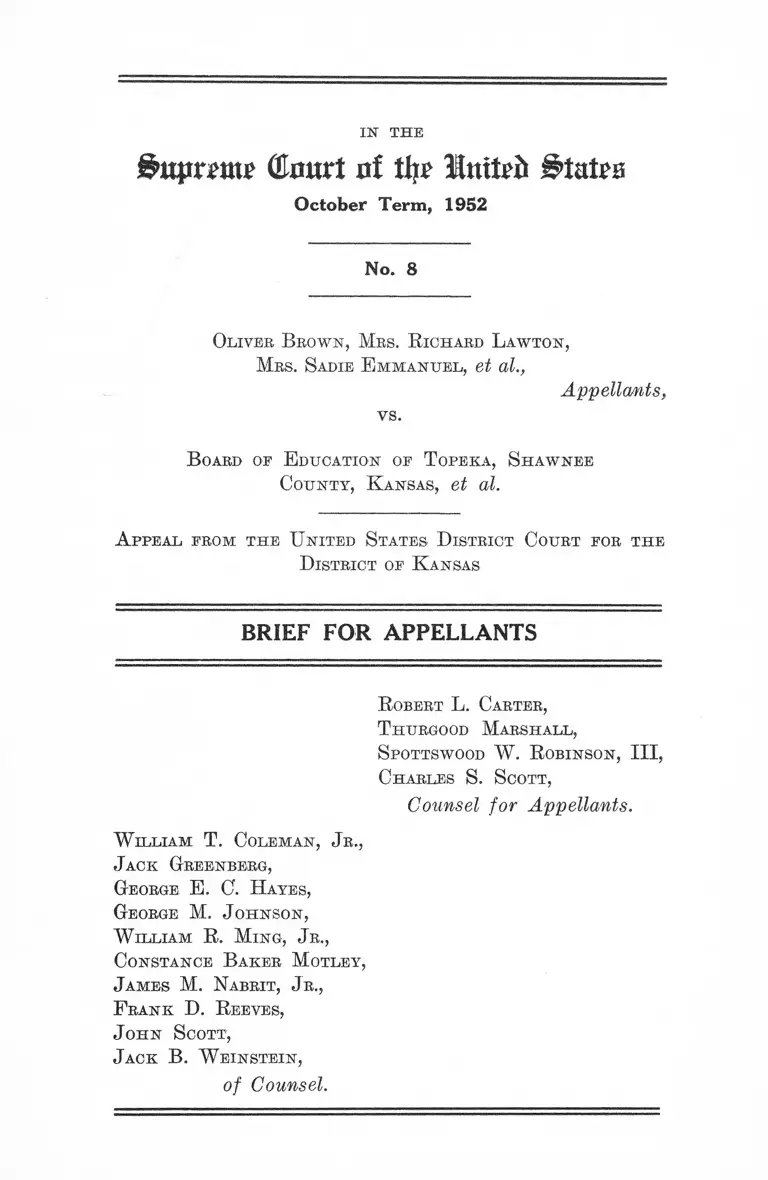

Brown v. Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1952. 7f2767cf-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/05fa0def-2645-4723-863f-310a27f7f414/brown-v-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

&uprmp (Cmtrt of % Inttefc £>ttxt?$

October Term, 1952

IN THE

No. 8

Oliver B ro w n , M rs. R ichard L aw to n ,

M rs. S adie E m m a n u e l , et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

B oard of E ducation of T opeka , S h aw n ee

Co u n ty , K ansas, et al.

A ppeal from th e U nited S tates D istrict C ourt for th e

D istrict of K ansas

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

R obert L . Carter,

T hurgood M arsh all ,

S pottswood W. R obinson , III,

C harles S. S cott,

Counsel for Appellants.

W illiam T. Colem an , Jr.,

J ack Greenberg,

G eorge E . C. H ayes,

G eorge M. J ohn son ,

W illiam R . M ing , J r .,

C onstance B aker M otley,

J am es M. N abrit, J r .,

F ran k D . R eeves,

J o h n S cott,

J ack B. W ein stein ,

of Counsel.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinion Below ...............................................................

Jurisdiction ....................................................................

Questions Presented ......................................................

The Law of Kansas and the Statute Involved.............

Statement of the Case ..................................................

Specifications of Error ...................................................

Summary of Argument..................................................

Argument .........................................................................

I. The State of Kansas in affording opportunities

for elementary education to its citizens has no

power under the Constitution of the United

States to impose racial restrictions and distinc

tions .....................................................................

1

1

2

2

3

4

5

6

6

II. The court below, having found that appellants

were denied equal educational opportunities by

virtue of the segregated school system, erred

in denying the relief prayed................................ 8

Conclusion........................................................................ 13

Table of Cases

Asbury Hospital v. Cass County, 326' U. S. 207 ............. 6

Bain Peanut Co. v. Pinson, 286 U. S. 499 ..................... 6

Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 2 8 ......... 8

Buchanan v. War ley, 245 U. S. 6 0 .................................. 7

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282 ....................................... 8

Cartwright v. Board of Education, 73 K. 32, 84 P. 383

(1906) ........................................................................... 2

Dominion Hotel v. Arizona, 249 U. S. 265 .................... 6

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160 ............................ 7

Ex parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283 ...................................... 7

Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147 ....................................... 7

Gong Lum v. Bice, 275 U. S. 7 8 ......... ..............5,10,11,12

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. 8. 400 ........................................... 8

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81 ................ 7

Knox v. Board of Education, 54 K. 152, 25 P, 616

(1891) ........................................................................... 2

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214 ................... 7

Lindsley v. Natural Carbonic Gas Co., 220 U. S. 61 .. 6

McLaurin v. Board of Begents, 339 U. S. 637 . . . . 6, 7, 8,10,

11,12,13

Metropolitan Casualty Insurance Co. v. Brownell, 294

U. S. 580 ....................................................................... 6

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 ......... 12

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 ............................ 7

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 7 3 ....................................... 7

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633 ................................ 7

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354 ...................... 8

Plessy y. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ............................ 5,10,11

Bailway Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 8 8 ......... 8

Bowles v. Board of Education, 76 K. 361, 91 P. 88

(1907) ........................................................................... 2

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 .................................... 7, 8

Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U. S. 5 0 ............................... 7

Sipuel v. Board of Begents, 332 U. S. 631 .................... 8

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535 ............................ 7

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 .................................. 8

Sweat! v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ........... 6, 7, 8,10,11,12,13

11

PAGE

I l l

PAGE

Takahaslii v. Fisk and Game Commission, 334 U. S.

410 ................................................................................. 7

Thurman-Watts v. Board of Education, 115 K. 328, 222

P. 123 (1924) ................................................................ 2

Webb v. School District, 167 K. 395, 206 P. 2d 1066

(1949) ................................................................. 2

Woolridge, et al. v. Board of Education, 98 K. 397,

157 P. 1184 (1916) .......................................................... 2

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 II. S. 356 ................................ 7

IN THE

(Emtrt of tho luttth

October Term, 1952

No. 8

o-

Oliver B ro w n , M rs. R ichard L aw to n ,

M rs. S adie E m m a n u e l , at al.,

Appellants,

vs.

B oard op E ducation op T opeka, S h aw n ee

C o u n ty , K ansas, et al.

A ppeal prom th e U nited S tates D istrict Court por th e

D istrict op K ansas

----------------------o----------------------

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Opinion Below

The opinion of the statutory three-judge-District Court

for the District of Kansas (R. 238-244) is reported at 98

F. Supp. 797.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the court below was entered on August

3, 1951 (R. 247). On October 1, 1951, appellants filed a

petition for appeal (R. 248), and an order allowing the

appeal was entered (R. 250). Probable jurisdiction was

noted on June 9, 1952 (R. 254). Jurisdiction of this Court

rests on Title 28, United States Code, §§ 1253 and 2201(b).

2

Questions Presented

1. Whether the State of Kansas has power to enforce

a state statute pursuant to which racially segregated public

elementary schools are maintained.

2. Whether the finding of the court below—that racial

segregation in public elementary schools has the detri

mental effect of retarding the mental and educational devel

opment of colored children and connotes governmental ac

ceptance of the conception of racial inferiority—compels

the conclusion that appellants here are deprived of their

rights to share equally in educational opportunities in vio

lation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

The Law of Kansas and the Statute Involved

All boards of education, superintendents of schools and

school districts in the state are prohibited from using race

as a factor in affording educational opportunities in the

public schools within their respective jurisdictions unless

expressly empowered to do so by statute. Knox v. Board

of Education, 54 K. 152, 25 P. 616 (1891); Cartwright v.

Board of Education, 73 K. 32, 81 P. 382 (1906); Bowles

v. Board of Education, 76 Iv. 361, 91 P. 88 (1907); Wool-

ridge, et al. v. Board of Education, 98 K. 397, 157 P. 1184

(1916); Thurman-Watts v. Board of Education, 115 K.

328, 222 P. 123 (1924); Webb v. School District, 167 K. 395,

206 P. 2d 1066 (1949).

Segregated elementary schools in cities of the first class

are maintained solely pursuant to authority of Chapter 72-

1724 of the General Statutes of Kansas, 1949, which reads

as follows:

“ Powers of board; separate schools for white

and colored children; manual training. The board

of education shall have power to elect their own

3

officers, make all necessary rules for the government

of the schools of such city under its charge and con

trol and of the board, subject to the provisions of

this act and the laws of this state; to organize and

maintain separate schools for the education of white

and colored children, including the high schools in

Kansas City, Kans.; no discrimination on account

of color shall be made in high schools except as pro

vided herein; to exercise the sole control over the

public schools and school property of such city; and

shall have the power to establish a high school or

high schools in connection with manual training and

instruction or otherwise, and to maintain the same

as a part of the public-school system of said city.

(G. S. 1868, Ch. 18, § 75; L. 1879, Ch. 81, § 1; L. 1905,

Ch. 414, §1 ; Feb. 28; R. S. 1923, §72-1724.)”

Statement of the Case

Appellants are of Negro origin and are citizens of the

United States and of the State of Kansas (R. 3-4). Infant

appellants are children eligible to attend and are now

attending elementary schools in Topeka, Kansas, a city

of the first class within the meaning of Chapter 72-1724,

General Statutes of Kansas, 1949, hereinafter referred to

as the statute. Adult appellants are parents of minor

appellants and are required by law to send their respective

children to public schools designated by appellees (R. 3-4).

Appellees are state officers empowered by state law to

maintain and operate the public schools of Topeka, Kansas.

For elementary school purposes, the City of Topeka is

divided into 18 geographical divisions designated as terri

tories (R. 24). In each of these territories one elemen

tary school services white children exclusively (R. 24). In

addition, four schools are maintained for the use of Negro

children exclusively (R. 11, 12). These racial distinctions

4

are enforced pursuant to the statute. In accordance with

the terms of the statute there is no segregation of Negro

and white children in junior and senior high schools (R. 12).

On March 22, 1951, appellants instituted the instant

action seeking to restrain the enforcement, operation and

execution of the statute on the ground that it deprived them

of equal educational opportunities within the meaning of

the Fourteenth Amendment (R. 2-7). In their answer,

appellees admitted that they acted pursuant to the statute,

and that infant appellants were not eligible to attend any

of the 18 white elementary schools solely because of their

race and color (R. 12). The Attorney General of the State

of Kansas filed a separate answer for the specific purpose

of defending the constitutional validity of the statute in

question (R. 14).

Thereupon, the court below was convened in accordance

with Title 28, United States Code, § 2284. On June 25-26,

a trial on the merits took place (R. 63 et seq.). On August

3, 1951, the court below filed its opinion (R. 238-244), its

findings of fact (R. 244-246), and conclusions of law (R.

246-247), and entered a final judgment and decree in

appellees’ favor denying the injunctive relief sought (R.

247).

Specifications of Error

The District Court erred:

1. In refusing to grant appellants’ application for a

permanent injunction to restrain appellees from acting

pursuant to the statute under which they are maintaining

separate public elementary schools for Negro children

solely because of their race and color.

2. In refusing to hold that the State of Kansas is with

out authority to promulgate the statute because it enforces

5

a classification based upon race and color which is violative

of the Constitution of the United States.

3. In refusing to enter judgment in favor of appellants

after finding that enforced attendance at racially segregated

elementary schools was detrimental and deprived them of

educational opportunities equal to those available to white

children.

Summary of Argument

The Fourteenth Amendment precludes a state from

imposing distinctions or classifications based upon race

and color alone. The State of Kansas has no power there

under to use race as a factor in affording educational oppor

tunities to its citizens.

Racial segregation in public schools reduces the bene

fits of public education to one group solely on the basis of

race and color and is a constitutionally proscribed distinc

tion. Even assuming that the segregated schools attended

by appellants are not inferior to other elementary schools

in Topeka with respect to physical facilities, instruction

and courses of study, unconstitutional inequality inheres

in the retardation of intellectual development and distor

tion of personality which Negro children suffer as a result

of enforced isolation in school from the general public

school population. Such injury and inequality are estab

lished as facts on this appeal by the uncontested findings

of the District Court.

The District Court reasoned that it could not rectify

the inequality that it had found because of this Court’s

decisions in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 IT. S. 537 and Gong

Lum v. Rice, 275 IJ. S. 78. This Court has already decided

that the Plessy case is not in point. Reliance upon Gong

Lum v. Rice is mistaken since the basic assumption of that

case is the existence of equality while no such assumption

6

can be made here in the face of the established facts.

Moreover, more recent decisions of this Court, most notably

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 and McLcmrin v. Board of

Regents, 339 U. S. 637, clearly show that such hurtful

consequences of segregated schools as appear here con

stitute a denial of equal educational opportunities in viola

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment. Therefore, the court

below erred in denying the relief prayed by appellants.

ARGUMENT

I

The State of Kansas in affording opportunities for

elementary education to its citizens has no power under

the Constitution of the United States to impose racial

restrictions and distinctions.

While the State of Kansas has undoubted power to

confer benefits or impose disabilities upon selected groups

of citizens in the normal execution of governmental func

tions, it must conform to constitutional standards in the

exercise of this authority. These standards may be

generally characterized as a requirement that the state’s

action be reasonable. Keasonableness in a constitutional

sense is determined by examining the action of the state

to discover whether the distinctions or restrictions in issue

are in fact based upon real differences pertinent to a lawful

legislative objective. Bam Peanut Co. v. Pinson, 282 U. S.

499; Lindsley v. Natural Carbonic Gas Co., 220 U. S. 61;

Asbury Hospital v. Cass County, 326 U. S. 207; Metropoli

tan Casualty Insurance Co. v. Brownell, 294 U. S. 580;

Dominion Hotel v. Arizona, 249 U. S. 265.

When the distinctions imposed are based upon race and

color alone, the state’s action is patently the epitome of

7

that arbitrariness and capriciousness constitutionally un

permissive under our system of government. Yick Wo v.

Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356; Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S.

535. A racial criterion is a constitutional irrelevance,

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160, 184, and is not saved

from condemnation even though dictated by a sincere

desire to avoid the possibility of violence or race friction.

Buchanan v. Worley, 245 TJ. S. 60; Morgan v. Virginia,

328 U. S. 373. Only because it was a war measure designed

to cope with a grave national emergency was the federal

government permitted to level restrictions against persons

of enemy descent. Hirahayashi v. United States, 320 U. S.

81; Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633. This action,

“ odious,” Hirahayashi v. United States, supra, at page

100, and “ suspect,” Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S.

214, 216, even in times of national peril, must cease as

soon as that peril is past. Ex Parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283.

This Court has found violation of the equal protection

clause in racial distinctions and restrictions imposed by

the states in selection for jury service, Shepherd v.

Florida, 341 U. S. 50; ownership and occupancy of real

property, Shelley v. Kramer, 334 U. S. 1; Buchanan v.

Warley, supra; gainful employment, Takahashi v. Fish

and Game Commission, 334 U. S. 410; voting, Nixon v.

Condon, 286 U. S. 73; and graduate and professional educa

tion. McLaurin v. Board of Regents, supra; Sweatt v.

Painter, supra. The commerce clause in proscribing the

imposition of racial distinctions and restrictions in the

field of interstate travel is a further limitation of state

power in this regard. Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373.

Since 1940, in an unbroken line of decisions, this Court

has clearly enunciated the doctrine that the state may not

validly impose distinctions and restrictions among its

citizens based upon race or color alone in each field of

governmental activity where question has been raised.

8

Smith v, Allwright, 321 U. S. 649; Sipuel v. Board of

Education, 332 U. S. 631; Sweatt v. Painter, supra; Pierre

v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354; Hill v. Texas, 316 TJ. S. 400;

Morgan v. Virginia, supra; McLaurin v. Board of Regents,

supra; Oyama v. California, supra; Takahashi v. Fish and

Game Commission, supra; Shelley v. Kraemer, supra;

Shepherd v. Florida, supra; Cassell v. Texas; 339 U. S.

282. On the other hand, when the state has sought to protect

its citizenry against racial discrimination and prejudice,

its action has been consistently upheld, Railway Mail

Association v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88, even though taken in

the field of foreign commerce. Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v.

Michigan, 333 U. S. 28.

It follows, therefore, that under this doctrine, the

State of Kansas which by statutory sanctions seeks to

subject appellants, in their pursuit of elementary educa

tion, to distinctions based upon race or color alone, is here

attempting to exceed the constitutional limits to its au

thority. For that racial distinction which has been held

arbitrary in so many other areas of governmental activity

is no more appropriate and can be no more reasonable in

public education.

II

The court below, having found that appellants

were denied equal educational opportunities by virtue

of the segregated school system, erred in denying the

relief prayed.

The court below made the following finding of fact:

“ Segregation of white and colored children in

public schools has a detrimental effect upon the

colored children. The impact is greater when it has

the sanction of the law; for the policy of separating

9

the races is usually interpreted as denoting the in

feriority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority

affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segrega

tion with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency

to retard the educational and mental development of

negro children and to deprive them of some of the

benefits they would receive in a racially integrated

school system.”

This finding is based upon uncontradicted testimony

that conclusively demonstrates that racial segregation

injures infant appellants in denying them the opportunity

available to all other racial groups to learn to live, work

and cooperate with children representative of approxi

mately 90% of the population of the society in wdiieh they

live (R. 216); to develop citizenship skills; and to adjust

themselves personally and socially in a setting comprising

a cross-section of the dominant population (R. 132). The

testimony further developed the fact that the enforcement

of segregation under law denies to the Negro status, power

and privilege (R. 176); interferes with his motivation for

learning (R. 171); and instills in him a feeling of inferiority

(R. 169) resulting in a personal insecurity, confusion and

frustration that condemns him to an ineffective role as

a citizen and member of society (R. 165). Moreover, it

was demonstrated that racial segregation is supported by

the myth of the Negro’s inferiority (R. 177), and where,

as here, the state enforces segregation, the communuity at

large is supported in or converted to the belief that this

myth has substance in fact (R. 156, 169, 177). It was

testified that because of the peculiar educational system

in Kansas that requires segregation only in the lower

grades, there is an additional injury in that segregation

occurring at an early age is greater in its impact and

more permanent in its effects (R. 172) even though there

is a change to integrated schools at the upper levels.

10

That these conclusions are the consensus of social

scientists is evidenced by the appendix filed herewith.

Indeed, the findings of the court that segregation constitutes

discrimination are supported on the face of the statute

itself where it states that: “ * * * no discrimination on ac

count of color shall be made in high schools except as

provided herein * * * ” (emphasis supplied).

Under the Fourteenth Amendment equality of educa

tional opportunities necessitates an evaluation of all factors

affecting the educational process. Sweatt v. Painter, supra;

McLaurin v. Board of Regents, supra. Applying this

yardstick, any restrictions or distinction based upon race

or color that places the Negro at a disadvantage in relation

to other racial groups in his pursuit of educational oppor

tunities is violative of the equal protection clause.

In the instant case, the court found as a fact that appel

lants were placed at such a disadvantage and were denied

educational opportunities equal to those available to white

students. It necessarily follows, therefore, that the court

should have concluded as a matter of law that appellants

were deprived of their right to equal educational oppor

tunities in violation of the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

Under the mistaken notion that Plessy v. Ferguson and

Gong Lum v. Rice were controlling with respect to the

validity of racial distinctions in elementary education, the

trial court refused to conclude that appellants were here

denied equal educational opportunities in violation of their

constitutional rights. Thus, notwithstanding that it had

found inequality in educational opportunity as a fact, the

court concluded as a matter of law that such inequality did

not constitute a denial of constitutional rights, saying:

“ Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, and Gong

Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78, uphold the constitution

11

ality of a legally segregated school system in the

lower grades and no denial of due process results

from the maintenance of such a segregated system

of schools absent discrimination in the maintenance

of the segregated schools. We conclude that the

above-cited cases have not been overruled by the later

case of McLaurm v. Oklahoma, 339 U. S. 637, and

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629.”

Plessy v. Ferguson is not applicable. Whatever doubts

may once have existed in this respect were removed by this

Court in Sweatt v. Painter, supra, at page 635, 636.

Gong Lum v. Rice is irrelevant to the issues in this

case. There, a child of Chinese parentage was denied admis

sion to a school maintained exclusively for white children

and was ordered to attend a school for Negro children.

The power of the state to make racial distinctions in its

school system was not in issue. Petitioner contended that

she had a constitutional right to go to school with white

children, and that in being compelled to attend school with

Negroes, the state had deprived her of the equal protection

of the laws.

Further, there was no showing that her educational

opportunities had been diminished as a result of the state’s

compulsion, and it was assumed by the Court that equality

in fact existed. There the petitioner was not inveighing

against the system, but that its application resulted in

her classification as a Negro rather than as a white

person, and indeed by so much conceded the propriety of

the system itself. Were this not true, this Court would

not have found basis for holding that the issue raised was

one “ which has been many times decided to be within the

constitutional power of the state” and, therefore, did not

“ call for very full argument and consideration.”

12

In short, she raised no issue with respect to the state’s

power to enforce racial classifications, as do appellants

here. Rather, her objection went only to her treatment

under the classification. This case, therefore, cannot be

pointed to as a controlling precedent covering the instant

case in which the constitutionality of the system itself is

the basis for attack and in which it is shown the inequality

in fact exists.

In any event the assumptions in the Gong Lum case have

since been rejected by this Court. In the Gong Lum case,

without “ full argument and consideration,” the Court

assumed the state had power to make racial distinctions

in its public schools without violating the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and assumed the

state and lower federal court cases cited in support of this

assumed state power had been correctly decided. Lan

guage in Plessg v. Ferguson was cited in support of these

assumptions. These assumptions upon full argument and

consideration were rejected in the McLaurin and Sweatt

cases in relation to racial distinctions in state graduate

and professional education. And, according to those cases,

Plessg v. Ferguson, is not controlling for the purpose of

determining the state’s power to enforce racial segregation

in public schools.

Thus, the very basis of the decision in the Gong Lum

case has been destroyed. We submit, therefore, that this

Court has considered the basic issue involved here only in

those cases dealing with racial distinctions in education at

the graduate and professional levels. Missouri ex rel.

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337; Sipuel v. Board of Edu

cation, supra; Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147; Sweatt v.

Painter, supra; McLaurin v. Board of Regents, supra.

In the McLaurin and Sweatt cases, this Court measured

the effect of racial restrictions upon the educational devel

opment of the individual affected, and took into account the

13

community’s actual evaluation of the schools involved. In

the instant case, the court below found as a fact that racial

segregation in elementary education denoted the inferiority

of Negro children and retarded their educational and men

tal development. Thus the same factors which led to the

result reached in the McLaurin and Sweatt cases are pres

ent. Their underlying principles, based upon sound analy

ses, control the instant case.

Conclusion

In light of the foregoing, we respectfully submit that

appellants have been denied their rights to equal educa

tional opportunities within the meaning of the Fourteenth

Amendment and that the judgment of the court below

should be reversed.

R obert L. Carter,

T hxjrgood M arshall ,

S pottswood W. R obinson , III,

C harles S. S cott,

Counsel for Appellants.

W illiam T. Colem an , Jr.,

J ack G reenberg,

George E. C. H ayes,

George M. J oh n son ,

W illiam R . M in g , Jr.,

C onstance B aker M otley,

J am es M. N abrit, J r .,

F r an k D . R eeves,

J o h n S cott,

J ack B . W ein stein ,

of Counsel.

S uprem e P r in t in g Co., I nc ., 41 Murray Street, N. Y. 7, BA 7-0349

49