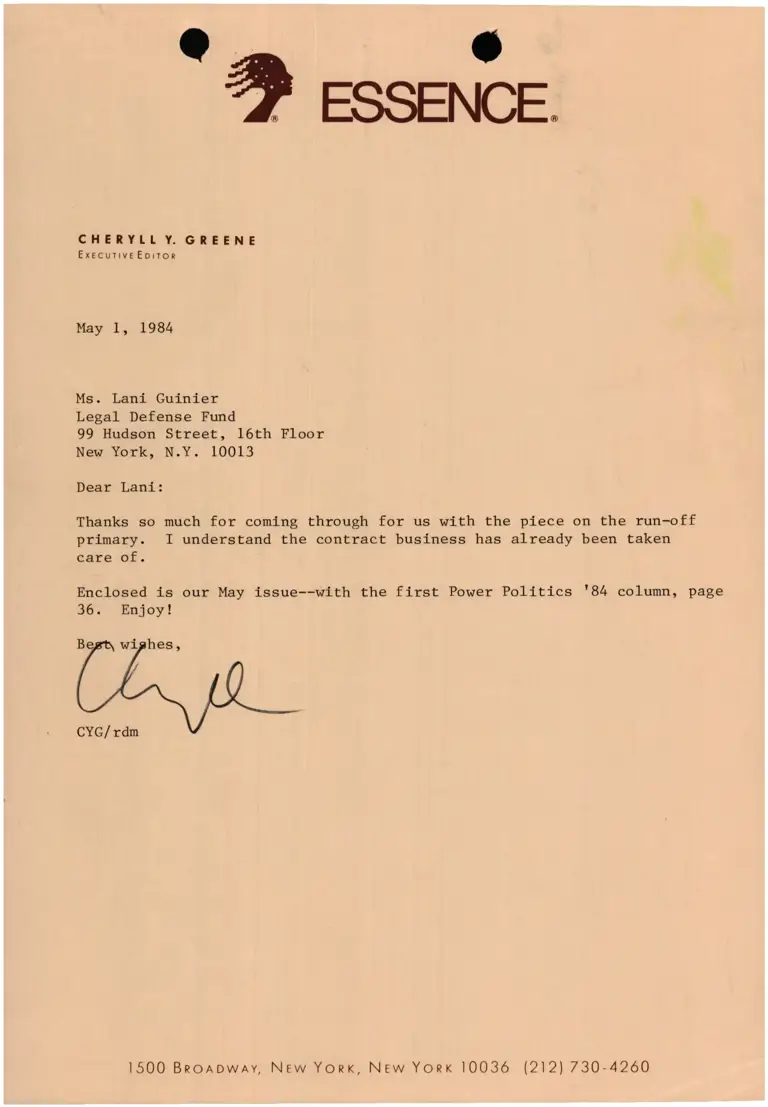

Letter from Cheryll Y. Greene to Lani Guinier

Correspondence

May 1, 1984

1 page

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Letter from Cheryll Y. Greene to Lani Guinier, 1984. 1f494606-e692-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/06814ee1-dbce-4bc4-870f-f068c9e0f29e/letter-from-cheryll-y-greene-to-lani-guinier. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

CHETYIT Y. GTEENE

ExEcurrvr Eorror

May I, 1984

Ms. Lani Gulnier

Legal Defense Fund

99 Hudson Street, 15th tr'loor

New York, N.Y. 10013

Dear Lanl:

Thanks so much for comLng through for us wlth the piece on the run-off

prlnary. I understand the contract buslness has already been taken

care of.

Enclosed ls our May lssue--wtth the flrst Power Polltlcs t84 columnr PaBe

36. EnJoy!

1500 BRoADwAy, Nrw Yonr, New Yonx 10036 .212]1730-4260