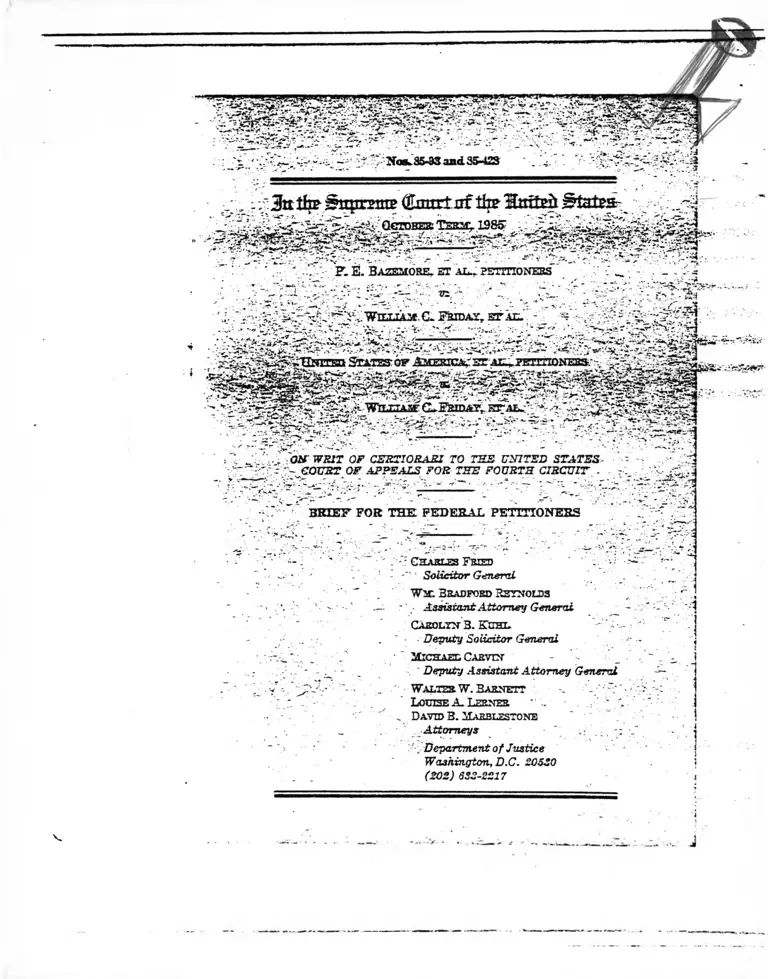

Bazemore v. Friday Brief for the Federal Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bazemore v. Friday Brief for the Federal Petitioners, 1986. 8cfd2a06-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0692fce2-c0ff-438a-898e-007f9966023d/bazemore-v-friday-brief-for-the-federal-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

V ,

«I ;

TABLE of contents

Page

OpiniotiB below *

......... 2Jurisdiction..........................................................-..............

2

Statutes involved .............................................

Statement ................................................................................

r , 12Snmmnry or argument ........................................................

Argument:

I. Black slate employees establish a claim under

Title VII by Identifying current salary dispari

ties between tliemaelvea and white employeea

bolding tbe same jobs and demonstrating that

p„cb disparities result from a slate policy be

fore 15)05 of paying blacks lower salaries than

whites ..........................................................................

II. The regression analyses showed racial discrimi

nation, and respondents did not refute that

showing ........................................................................

A. In order to establish a priina facie of snl-

nry discrimination, a regression analysis

must control for factors that normally alfect

. . . . . 22 sa la ry ................................................................

B. Tbe court of appeals erred in analyzing tbe

statistical proof offered in this case ............ 28

IN. Tbe service retains joint responsibility for Ibe

selection or county chairmen, and is therefore

liable under Title VII for discrimination in ^

those selections..........................................................

IV Prior segregation in the I I I and extension

homemaker clubs was rally cured by respon

dents’ adoption of a genuinely nondiscriminatory

admissions policy.................... ..................................

, . ........... GOConclusion ..........................................................

(tit)

IV

TAHIjR o r AUTllOUITIRS

Cnses: 1,nR0

Aclia. V. Bcarnc, 570 F.2d 57 ..................................... ^

Alabama Slate Teachers' Ass'n v. Alabama Public

School & College Authority, 280 F. Siipp. 781,

nlT’d, 808 U.S. 100 ............................... 40

Alexander v. llolmc*, 800 U.S. 10 41

American Tobacco Co. V. Patternon, 150 U.S. 08 ... 17, 20

Atonio V. I I'd i d i Cove. Packing Co., 708 F.2«1 1120 . 80

llartclt v. Itcrlitz School of Language of America,

■ Inc., 008 F.2tl 1008, cert, denial, 101 U.S. 015.. 10

Derry V. Hoard of Supervisors of Loniaiana Stale

University, 715 F.2<l 0 7 1 .......................................... 49

Bowman v. County School Board, 882 I’ .2d 320.... 47

Drown v. ltd. of L'duc.:

347 U.S. 483 .......................................................... 40

340 U.S. 201 ........................................................... 40, 41

Colombo* ltd. of Kduc. V. Pcnick, 113 U.S. 440.. 38, 47

Corning (Ha** Work* V. Brennan, 417 U.S. 188 20

Cox V. Stanton, 520 F.2d 4 7 ........................................... 44

Dayton ltd. of Kduc. v. Brinkman:

433 U.S. 400 ......................................................... 40-41,45

443 U.S. 520 ............................................................. 48

Uothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321.......................... 20

Duma* V. Town of Mount Vernon, 012 F.2d 074. .. 17

Ea*Hand v. Tennc**cc Valley Authority, 704 F.2d

013 ................................................................................ „

Farmer v. A It A Service*, Inc., 000 lp.2d 1000....... 35-3G

Fnrnco Construction Cory. V. Water*, 438 U.S.

507 ................................................................................. Z2> 20

Coyle V. Browder, 352 U.S. 008.................................. 40

General Building Contractor* A**'n V. Pennsyl

vania, 458 U.S. 875 ................................................ 2r*

Co** V. ltd. of Kduc., 373 U.S. 083 ...........................

Green v. School Board, 301 U.S. 430 41,43, 40, 47, 48, 40

Griffin V. Carlin. 755 I'.2d 1510 ....................... 25

Guardian* v. Civil Service Commission, 403 U.S.

583 .... ........................................................................

Hall V. Led ex, Inc., 000 F.2d 307 ............................. 10

!

V

Cnacs—Continued: ' ”R0

Hazelwood School Hiatrict V. United Slate*, 188

U.S. 200 ......................................... -........................... passim

Holme* v. City of Atlanta, 850 U.S. 870 ................ 40

International Brotherhood of Teamster* V. United

Slate*, 431 U.S. 3 2 1 ............................40, 20, 22, 25, 20, 27

Jenkins V. Home Insurance Co., 035 F.2d 3 10 ...... 18

Keyes V. School District No. I, 413 U.S. 180....... .11,40

Kim v. Coppin. Slate College, 002 F.2d 1055 .............

Lamylierr v. Brown University, 085 F.2d 743....... 10

Manor of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U.S. 877 40

McDonnell Douglas Cory. v. Green, 411 U.S. 702 20

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Tran*p. Co., 427 U.S.

273 ............................................................................... 36

Millikrn V. Bradley:

418 U.S. 717 ................................................... 40, 41,40

433 U.S. 207 .......................................................... 40,41

Moose Lodge No. 107 v. Irvis, 407 U.S. 103 40

Monroe V. Board of Commissioners, 301 U.S. 450.. 40, 47,

48, 40

Muir V. Louisville Parle Theatrical Ass’n, 347 U.S.

071 ............................................................................... 40

Pasadena Bd. of Kduc. V. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424 40, 45, 40

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 580 F.2d 300 17

Perez V. Laredo Junior College, 700 F.2d 731 10

Pullman-Standard v. Swiut, 450 U.S. 273................. 17, 20

Raney v. Bd. of Kduc., 801 U.S. 443 ........................ 40

Robinson v. Lorillard Cory., 444 F.2d 701, cert.

dismissed, 401 U.S. 1000 ......................................... 30

Salz V. ITT Financial Cory., 019 F.2d 738 10

Segar V. Smith, 738 F.2d 1240, celt, denied, No.

84-1200 (May 20, 1085) .................................... 25,84

Syeneer V. Kugle.r, 401 U.S. 1027.......................... - ^0

St. Marie v. Eastern R.R. Assn , 050 F.2d 305 25, 27

Swann v. Bd. of Kduc.. 102 U.S. I ..... 40, 41, 42, 45, 40, 47

Texas Department of Community Affairs V. Bur

dina, 450 U.S. 218 ............................... 22,25,20,27

Trout v. Lehman, 702 F.2d 1001, rov'd, 405 U.S.

1050 ................. 25

United Air Lines, Inc. v. Keans, 431 U.S. 558 .10, 12, I I,

15, 10, 17, 18, 10

VI

Cascn—Continued: ' B8°

United Stairs Postal Service Hoard of Governors

V. Athens, Kid U.S. 711 .................... ..................... Z8’ 8jl

Valentino V. H.S. Postal Service, 674 F.2d 56.......

Washinfllon v. Davis, 426 U.S. 22!) ..... - ................. 40

Wilkins v. Vniversitfi of Houston, 651 F.2d *188. .. 25

Constitution, plain tea and rcRulalion:

U.S. Count. Amend. X IV ............................................4> 38, 40

Civil UIrIiIh Actor 1564,42 U.S.C. IdRI el serf.:

Tit. VI, 5 lidI. 12 U.S.C. 2dddd .................. Z, 4

Tit. VII, 42 U.S.C. 2000c et seq.:

§ 708, 42 U.S.C. 2000C-2 ............................... 4

§ 703(a ) (1 ) , 42 U.S.C. 20d0c-2(n)(i) .... 2

§703(li), 42 U.S.C. 2000c-2(1i) 17

|?<|unl Pay Act, 2!) U.S.C. 206 ..................................... z8

42 U.S.C. 1081 :

7 C .F.lt. 15.3(b) (0) (i) .....................

Miscellaneous:

Flnkclnlein, Regression Models in Administrative

Proceedings, R6 llarv. L. Ilev. 1442 (1073)....... 28

Flnlier Multiple Regression in Legal Proceedings,

80 Colnm. I , ltcv. 702 (1080) ......................... 23,24,26

j ilt l l f r g i t p r r iH r ( f ln u r t n f l l ip I t i iU r i ) S l u l r n

O otoheii T e r m , 1985

No. 85-93 11

V. R. llAZEMOUE, ET Al,., p e t i t i o n mis

• 11

V.

WlliMAM C. FRIDAY, ET, Ale

No. 85-428

U n it e k S t a t e s o f A m e iu c a , bt a e ., p e t it io n e iir

v.

W ie e ia m C. F r iday , e t a l .

ON W RIT O F C E R T IO R A R I TO T I IE U N IT E D S T A T E S

CO U R T o r A P P E A L S POR T H E FO U R TH C IR C U IT

IIUIFiF FUll T ill? FI?m?IIAI, PETITIONERS

OPINIONS IIEI<OW

The opinion of llte court of appeals (Pci. App. 346a-

481a)' in reported at 751 F.2d 662. Tlie opinions of the

I "Pet. App." re fern to I he separately I round appendix filed with

the petition in No. S5-D3. In (proting materials fruni this appendix,

we have corrected typographical errors in the IIIIiir ; those correc

tions are inilicaled by brackets. "Rupp. Pet. App.” refers to the

supplementary appendix hound with Ilia petition in No. 85-428.

"J.A.” refers to Ihc separately hound appendix filed with this br ief.

"(!.A. App." refers to the JO-volumc court of appeals appendix,

10 copies of which have been lodged willi this Court. "('.A. H r.’

refers to the Itricf for the United Stales filed in tire court of ap

peals, 10 copies of which have also been lodged with this Court.

( 1 )

z

district court (I 'd . 3n-207», are on-

reirortcd.

.MIUIRDICTION

The judgment or Hie court or appeals ISupp. Ret. App.

ln-3a) was entered .... December 10 ,1984 WJ "

denied on April 15, 1985 (l’cl. App. 482a-483a). On

July 5 ]J)85, Hie Chief Justice extended the Covet n-

tncnl's time for filiitf' a petition for a writ of certiovan

to and Including September 12, 1985. 1 lie petition

No 85-93 was tiled on July 15, 1985, and the pel lion

in No. 85-428 was filed on September 12, 1985 l oth

petitions were granted on November 12, 1985 (J.A. iS i-

182). The jurisdiction or this Court is invoked under 28

U.S.C. 1254(1).

STATUTES INVOLVED

The relevant portions of Section 001 of ri ill« VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1904, 42 U.S.C. 2000d and Section

703(a)(1) or Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1904,

42 U.S.C. 2000o-2(a) (1), are reproduced at pages 3-4 o

the petition in No. 85-93.

STATEMENT

1 The North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service

(the Service) provides services to state residents involv

ing the dissemination or "useful and practical informa

tion on subjects relating to agriculture and home eco

nomics," c.fl-, through educational programs for fmnjcj-

and sponsoring 4-11 and extension homemaker clubs (le t.

App. 7a, 12a 20a). It is funded jointly by the United

States Department of Agriculture, the Slate of Nor '

Carolina, and the various counties in the Mate Met.

Ann. 7a-8a). The Service employs agricultural extension

agents, professional employees at the county level, o

which there are three ranks: full agent, associate agent,

2 T J L . I ''I'.... >■■*. Are- I7»i.

perform "essentially Hie same types of tasks, but tin

full agents have more responsibility and are expected to

maintain bielier performance levels than associate

I

I

agents, the intermediate position, or assistant agents, the

entry level position {ihitl. I .'i 1 1 ' „

Until August 1905, the Service Was1 divided into a

while branch * * * and a Negro branch * r * composed

entirely of black personnel and scrvlinjfl only black farm

ers, homemakers and youth” (Tel, App,, 27a). Although

black and while county agents had,,j^lcntical responsi

bilities and job descriptions (I’et. App. 29a), “ |l|he

salaries or black agents in the segregated system were

lower than the salaries of their while counterparts”

(Ret. App. 30a). The two branches'of the Service were

merged on August 1, 1905 (Ret. App. 30a, 359a), and a

single minimum entry level salary was adopted for all

agents hired alter the merger.*

Shortly heroic the merger, the position of county ex

tension chairman was created by making the white

county agents responsible for coordinating the cntiie ex

tension program in their respective counties (O.A. App.

1001-1002, 1783). In November 1972, the Service intro

duced a system of announcing job vacancies and accept

ing applications for county chairman positions (Ret. App.

24a-25a, 75a).' Applicants who possess I he minimum

quidifications for county chairman are interviewed by

Service ollicials, who then make a recommendation to the

board of county commissioners (Ret. App. 25a-25a, 7<>a-

2 |u ||,fa |„ | , .r we will use the term "iigcnls" to refer rollerlivcly

to nmploypcs in fill llirec rniiks.

a Newly III m l ngcntfi wllli inlvnnred df'grcc*, prior rrlovnnt cx-

iierience, or particularly ueeile.1 skills nre paid mere lluoi tl.c mini

m i , R , n - I i spent's snliiry slsu rellcets a conlriliullmi by

,.,.iiiilv in whirl, he is employed, lira nmouiit varying from euunly

p, eouuly Pay Increases nwanle.l by the comity or the stale may

he In the fern, of an e-i'nal stun I" earl, employee or as a percentage

„f the salary. I'll,ally, I he stale ami some counties provide To,

merit pay illn esses and inn eases to olfset inlhillon U’el. App.

JOita 115a, :il!0a-3li2a).

1 llrfme II,at lime, manly 'I,airmen were selected jomlly h.v

the Service ami the hoard of eonaly commissioners ronrerned from

a list or possible candidates prepared by the Service U'-A. App. It..',

,|ar> -ISM; Pel. App. loin).

1

77a). The county generally accepts the recommendation

(C.A. App. 171), hut "all appointments are worked out

jointly between the Extension Service and the commis

sioners and no oflicial action can he taken unilateinlly by

either parly with respect to Idling a vacancy” d ’et. App.

77a). . . . . .1

Prior to 15)05, the Service had established separate all-

white and all-black I II and extension homemaker clubs,

and many clubs presently have only members of a single

race (J.A. 100; C.A. App. 1807), although the number of

integrated Clubs increased nearly three-fold between

1972 and 1980 (C.A. App. 1807, 180, 1M0). After

1905, the Service requested a formal assurance from

each club that it would not discriminate on the basis or

race, color, or national origin (OX 115, at 3). lhe

Service has also published in the media its policy that

all voluntary clubs be organised without regard to race,

instructed its agents to encourage formation of new

clubs on that basis (Pel. App. 181a), and integrated all

other aspects of I be'l-II program.

2. a. This suit was initialed in November 1971 by

more than 50 black employees of the Service, alleging,

inter alia, intentional racial discrimination in employ

ment and services in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution, 12 U.S.C. 1981, and Section 601

of Title VI or the Civil Rights Act of 1904, 12 U.S.C.

2000d (Pet. App. On-la). After Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1901 became applicable to the stales in

1972 the complaint was amended to include claims under

Section 700 of that Act, 12 U.S.C. 200Uc-2, and the

United States intervened in the action. The complaint in

Intervention, as amended, also alleged racial discrimina-.

tion against black employees and recipients of services

In violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, Title VI, and

Title V I I (Pet. App. 5a, 35a). . . . .

Plaintiffs asserted intentional racial discrimination in

various Incidents or employment, including salaries, job

assignments and promotions, and in the selection of

county chairmen, as well as in the continued support of

5

. I tl\Y

single-race l-II and extension homemaker clubs (Pel.

App. 19a-5ta). The employment-related claims included

individual claims of discriminatory,..treatment as well

as allegations of intentional patterns >and practices of

discrimination (Pet. App. 19a-51a,' 227a-3,19a).

b. The case was tried to the court1 for It) weeks start

ing in December 1981 (Pet. App.' 4a),."'During discovery,

the defendants had asserted that .four, factors were de

terminative or salary: education,.tenure, job title and job

performance (GX 159, at 90, 9(5 (Oct! 1(5, 1981, Deposi

tion of Dr. Paul Dew, Assistant DilecW of County Op

erations)). At trial, Die evidence introduced by the

United Slates included multiple regression analyses

comparing the salaries of black and while county agents

in 1971, 1975 and 1981. Certain of these regressions used

four independent variables—race, education, (enure, and

job title—and showed a statistically significant racial

effect for 1971 (C.A. App. 1(501, 102-103) and 1975 (C.A.

App. 1589, 11(5), and a smaller racial effect, without sta

tistical significance, for 1981 (C.A. App. 1578)."

The district court indicated that, based on this evidence,

plaintiffs would prevail unless defendants produced statis

tical evidence demonstrating that the addition of other

variables would reduce or eliminate the racial effect."

Accordingly, defendants also introduced multiple regres

sion analyses, for 1975 and 1981. Certain of these re

gressions used the same variables ns plaintiffs' regres

sions, but excluded county chairmen from the data base,

and these analyses produced results similar to plain-

r. These instills were cm rnhoi iited by oilier evidence, includliiR

mi exhibit, l.nsnil on .? Mini my I »T,\ payroll data for 23 counties,

Unit shuweil 2!l blnck employees ear nine Ess Ilian whiles in lhe panic

enmity with eoinpnrnble or lower positions mill llie same 01 less

(enure anil education (C.A. App. 1503-1567).

« The court lolit respondents’ counsel (C.A. App. 525) :

11 |f miller the law nil those things should Imve been cranked

in there, and if after crmtkiiiR them in you pet a different

result. Ihen von win. If they ain’t Rot any business in there

or ir you've cranked Ihciii in and It sllll doesn't show it, then

lliey win.

G

tlfTa’ (C.A. App. 1710 (analyses), 1711-1712, 1001-16921.

In addition, defendants presented regressions that added

qua,tile rank, a measure of job performance, as an in

dependent variable.’ Doing so for 15181 produced statisti

cally insignificant racial disparities, but doing bo for

15)75 increas'd tbe racial effect, and Ibis result was statis

tically signilicant (O.A. App. 1710 (analysis G), 1713-

1714)). t . „ . .

Plaintiffs also introduced evidence showing lliat al

though the si/,c or the d-ll club system has varied consid

erably over the years, there have been more than 1,000

all-widte clubs each year since 15)72 (C.A. App. 2237; GX

11), and more than 850 single-race chibs in communities

identified by defendants as "ethnically mixed” (C.A. App.

1807) The extension homemaker clubs also remain

largely single-race clubs (J.A. 103-113; C.A. App. 1800-

1807; Tr. 941-942, 1524-1525, 235)0, 2449-2450)."

t Qunrlllu rnnU is usnl In determining merit salary Increases

(see note i)2, infra). I lie government did not use tills variable In

Its regression analyses because Die quarlllc system wns Itself under

allrnk In lids suit ns racially discriminatory (sec l ’et. App. 891a-

400a).

i ' f he govern men l also introduced statistical and oilier evidence

relating to the selection of county chairmen. The first black chair

man was not selected until March 1971, after 151 while chairmen

had been selected (J.A. 127; CX 75). Hclween November 1972

when the first vacancy announcement appeared (sec note 4, unpin)

and October 1981, 72 (93.5%) of the 77 county chairmen selected

were while and 5 <5.5%) were black (J.A. 114-124; C.A. App.

919-920). No black was selected for any of llic 31 positions filled

between November 1972 and July 1, 1975, although 12 (10.3%)

of the 115 applicants for those positions were black. Several blacks

testified tha t they bad not sought chairmanships because they be

lleved It would be futile to do so (I’et. App. 93a). Of the 5 blacks

among the candidates selected for the 15 positions filled between

July 1975 and October 1981, 3 were selected for vacancies for which

only blacks were in competition, and the sole while applicant with

which the other 2 competed was a female; no black bari ever been

selected In compelIIion with a white male applicant (J.A. l H ' - J

C.A. App. HMKt, MMM»; <JX 172, nt mc ^.A. *'

nt lOn-lln).

• . i

"• ill }•«* ll I

I • . I I I M

i i i . •*|i: i i

7 A|"

c TIip district court, rejected all dhims of the private

plaintiffs and the United States. With respect to the

salaries of county-level employees!, th6 court held that no

pattern or practice of racially discriminatory treatment

bad been shown (l’ol. App. 150a).„T|ie court noted hat

« |i | t is undisputed” that before Aha merger of its black

and while branches in 15)05, the Service paid black agents

loss than while ones, and recognised that, although "steps

were taken to begin |lhe| elimination” Of this disparity

before tbe Service was covered by Title Vlf in 15)72,

"the government has offered evidence lending to show

that as of January 15)73, the s:|la()es of numerous black

agents throughout the system were less than those or

white agents in the same counties who were in comparable

or lower positions and who bad comparable or less tenure

* * * |and 1 defendants’ own exhibit [showed | some sal

ary disparities between blacks and whites as late as Oc

tober, 15)74” (Pet. App. 120a-121a). The district court

nevertheless found that "while on its face libel evidence

unquestionably establishes salary disparities, when viewed

in the light of defendants’ explanatory evidence it fails to

prove discrimination” (I’et. App. 122a-123a)Focusing

on certain regressions that controlled only Tor tenure and

education (I’et. App. 131a), rather than on those also

ineluding job title and job performance as independent

variables, (lie court described the regression analyses as

v p r f .u o analyzing tlm statistical data, tbe court explained Its

nppruneb In Ibe rr.,iiirenicnls of the Civil Rights Act of 195 1 <1 cl.

App. I2 ln-I22n) :

, Uq| .,q It bml been fmiml in tbe area of education Ibal. there is

„„ nui'li tiling ns instnnl inlegrallnn. It was soon found In Ibe

Held nf business and industry tlmt tbere is no such tiling as

Instant |e | . |ua lity in employment. Without risking serin,is

disruption nf a business by prnblfb|lllvely cosily budgetary

nllcpillions and n possible practice of wholesale reverse d s-

crlmlnalion it was soon recognized (though not always by tbe

coiirl.nl lliat Ibe adjustments mandated by tbe law simply could

md; bo made overnight.

Tl„,s the "explanatory evidence” Ibe court viewed as justifying

(he salary disparities established by tbe government npparenlly

included ibe hisloricnt fact of discrimination.

8

flawed, primarily because the raw dal,a on wliich they

were based included the salaries of higher-paid county

chairmen, most of whom were white, as well as county

agents (Pet. App. t:iC.a-138a), and because tliey failed

to account for "several unmeasured factors, notably job

performance” (Pel. App. Mia).'" In sum, the court "con

clude! d | ‘ that (he plaintiffs had probably made out a

prima facie case with respect to defendants promotion

and salary practices * * * |bull the defendant

articulnlledl plausible reasons for its actions * * * which

the court found convincing” (Pel. App. 1!>()a).

As to the claim that the Service permitted segregated

4-11 clubs and extension homemaker clubs to bo main

tained in North Carolina, recognizing and providing serv

ices to such clubs, the district court found that tlicie aic

many clubs to which members of both races belong” (Pel.

App. KiGa). and that “ | i | f any individual lias become a

member of a club composed only of members of his oi

lier own race, it has been an entirely voluntary act (1 ct.

App. 172a). The court found no evidence of any denial of

membership or discrimination in services on the basis of

' •T h e court rolled on n lint of variation provided by defendants

(Pet. App. l!l!tn-l!Mn):

(1) Performance of agents measured against (lie ngenls'

plan of work;

(2) The variation in salaries created by aeronn the board

stale raises with the different percentage of alate contribu

tions In each county;

(2) The across Ibo board Increases in spent nnlnrles by

some counties and not in others;

(d) Tin* merit raises provided by Ibe slate;

(fi) The merit raises provided Tor by the counties in which

Extension Service personnel have no input;

(0) The merit raises provided by the counties with limited

or full participation in Ibe merit recommendation by Intension

Service personnel;

(7) The range in merit salary increases provided by Ibe

counties (0 | ! " l I2',’!> in Itiftl);

(fl) Prior and relevant experience; and

*' Variations in salary due to market demands both at

U,tm of hire and later for agents with skills in short supply or

m ine ernrrienre

i 1... ■ .1 .

■ I- 1 * toI.ml |

: ,1 lie .,■! '

' ’ . I I I I I ' lie

I i • ii h I • I ii

' I I ' ......

race, ami concluded that the lawi dues pat require that

these clubs be integrated (Pel. App. i !G5a-185a). I lie

court ruled that the evidence did not demonstrate any

discriminatory intent on the Services part in loleialing

the single-race clubs (Pet. App. 17Ha-182a), and Hint (lie

Service accordingly did not violate Ut# lAtV in coni liming

In provide services to slid) clubs (lfet. Ajtjp. 184a-185a)."

3. a. The court of appeals aflivnicpl (Pel. App. 34(5a-

125a), Judge Pliillips dissenting in pprt (Pet. App. 425a-

481a). The panel majority adopted ,1!)?, t)islriel court’s

lliiflings that under policies in effect when the Service

maintained two separate racially1 segregated branches,

black employees were paid less Iliad wllllc employees per

forming (lie same job because of their race, and Unit even

after (lie Service became subject to Title VII in I!17J,

"fs|onie pre-existing salary disparities continued to linger

on” (Pol, App. 3fi0a). However, Hie court staled suc

cinctly (Pet. App. 380a) :

The plaintiffs claim that the pre-Act discrimina

tory difference in salaries should have been allirma-

lively eliminated bill has not. We do not think (his

is the law.

n Tim (Unh id; court also held llmt the plaintiffs failed to estab-

Holi n pi inui facie rase or racial discrimination in Ibe select ion of

county chairmen, ami Hint “ in any event llie defendants have

elfecHvely rebutted plaintiffs’ case try showing the inaccuracy ami

insignificance of plnintiira’ proof” (Pet. App. 100a). I lie court

found that only 77 county chairman positions hnd lieen filled since

Hie institution of slnlewlde vacancy aiinnunccnicnls in 1072, Hie

year Title Vi I was made applicable to public employers, and Unit

Mocks bad applied for only IK or those positions (PH. App. 7Ka.

R5a-SI>al. Hnnsiiloring those IK positions (and thus including posi

tions for wldcli only blacks applied but excluding posilim.s for

which only whiles applied) Hie court found the selection rale for

Mocks occeplahle (Pel. App. 7!'a-K0a, R(in>, and held Uml Hie

Service’s selection procedures for county chairman have, since 1!>(2,

Item applied In a noiuliscriminatory manner (Pet. App. KKIa-IOla).

The court reieded plainlilfs’ claim that lilacks Imd Iscu deterred

from applvimr for chairmanships (Pel. App. IWn), and also rejected

all Individual claims or discrimination In promotions to counly

chairman (PH. App. 227a-3lfn).

10

The panel majority relied for its view on United Air

Lines, Inc. v. Leans, -IHI IJ.S. 053 (1077), and Hazelwood

School District v. United States, 433 IJ.S. 200 (1077), as

well as several court of appeals decisions that followed

Evans in rejecting lime-barred claims despite the con

tinuing c(Teels of (lie alleged discriminatory acts on sen

iority rights (IVI. App. 38(>a-3H2a). This view of Title

V ll’s requirement led (he panel to fault all of the regres

sion analyses of (lie salaries of current county employees

_recent hires as well as prc-Acl hi res—because the fig-.

ures analyzed "relied (lie elTect of prc-Act discrimina

tion” (Pet. App. 380a). For this reason, as well as be

cause "both experts omitted from their respeclivc anal-

ys|els variables which ought lo he reasonably viewed as

determinants of salary,” (he analyses were deemed "un

acceptable as evidence of discrimination (Pel. App.

301a).

With respect lo (lie selection of county chairmen, plain

tiffs challenged on appeal the district court’s analysis of

selection rales, arguing that the court erred in excluding

vacancies for which only whiles applied, while including

vacancies for which only blacks applied (Pet. App. 41 la-

412a). The court of appeals majority found it unneces

sary to consider these objections, because it concluded that

•The employment decisions made by the Intension Scrvieo

with respect lo I ho selection of County Chairmen were

made when the Service either recommended or did not

recommend an applicant for an existing vacancy lo the

County Commissioners” (Pet. App. 405a-40(5a). It there

fore examined (he dal a as (o I he Service’s recommenda

tions, rather than the selection statistics relied on by

plaintiffs and (lie district court, and found no discrimina

tion (Pet. App. 4180-4230).'=

is The court's initial analysis (IVI. App. 4i:in-l l4a), includes nil

positions for which Muck cnndldnlos applied, whether or not while

cnudhlntcs also competed, lint excludes positions for which only

while cnndidnles applied. The court’s more extended nnnlysls (id.

At 4IBn-42ln) includes "spplicuul How data” for nil positions filled

during the years 1008-1 PHI. In (lie Inller analysis, the court’s

references lo '’applicants" or "applications" during the period 11(08-V1 "

1,

■■ -li |».ll H I

11 "*'*(*' ' •" '•>

Finally, the panel majority hehUtwMJjp cn,"'t

“correctly denied (lie plaintiiTs’ clai^ .re.speeL to the

alleged allirmativc duly to require, integrated nicmbcr-

ship” in 4-11 clubs and extensionhppiqipaker elnlis be

cause, absent any proof of discrimination, "Ihe mere ex

istence of all while and all black .Pa* ' |c|lubs in some

racially mixed communities” does' Ml" Violate the law

(Pet. App. 424a n.128).

b. Judge Phillips dissented frclln' thP 'majority's dis

missal of the salary claims (Pet. ^iij).,,425a, 433a-4(i!la),n

noting that it was undisputed that prior to the 11X55

merger “Ihe salaries of black professionals were inten

tionally and quite openly simply Set ldwet* than those of

while colleagues in the same cmplpynl6lit positions’ (Pet.

App. 437a), and that these salary (liflerenlials continued

"well past l!M58 (the earliest limitatioii date applicable

to the salary claim)” (Pet. App,,438a-43!>a)." The

regression analyses of belli plaintiffs’ find defendants’ ex

ports were, moreover, in his view, "wholly consistent in

showing a substantial, across-the-board race-based dis

parity (Pet. App. 410a-450a). Because these analyses

“employfed| the most obvious alternative variables of

tenure, education, and job position” (I’ct. App. 4l!la),

Judge Phillips found no authority for rejecting such

analyses “for failure to include a number of oilier in

dependent variables merely hypothesized by defendants”

(Pet. App. 448a).

UI7I, when there were no vacancy announcement ami application

procedures, evidently refers lo the list of possible candidates pre

pared by Service ollleials, from which they later made recommendii-

llons lo the counties (see note I, supra); the’ court's references lo

white or black “approvals” refers lo the recommendations made by

the Service to the counties (see chart preceding I’et. App. 120a).

n | | (, „|!m dissented from Ihe majority’s rejection of the I II and

extension homemaker club claims (Pet. App. 425a, 400a-48la).

h As .fudge Phillips recognized the complaint, tiled in Novem

ber 1071, included claims based on the Constitution and Title VI;

the la tter lias been applicable lo ihe states since 11)01. A lliree-year

limitation period applies lo I hose claims. Cox V. Stanton, 520 l'\2d

47, 40 5(1 ( lib Clr. 1075).

1 2

In sum, Judge Phillips concluded Hint “the only ra-

lionnl assessment In ho made of the evidence in lids rec

ord” is Hint “Ihe general pattern of pre-J9(»5 overt dis

crimination in salary continued in substantial, if giudtt-

nlly diminishing, degree until at least 197(1 and perhaps

beyond,” and that responsible Service officials knew that

such a race-based pattern continued and failed to coricct

it (I’et. App. 455a-l5l»a). In bis view, the majority’s

failure to award relief on such a record resulted from

"misapprehensions of controlling legal principle’ (le t.

App. 45(ia), including the "relevant time frame within

which the existence of a pattern or practice of salary dis

crimination was to bo assessed” (Pet. App. 457a).,r’ ^

4. Rehearing on banc was denied by an equally divided

court, without opinion, on April 15, 1 !)F?5, and the panel,

Judge Phillips again dissenting, also declined to rehear

the case (Pel. App. 4<S2a-483a).

SUMMARY OF AltUllMICNT

Hiring and promotion decisions are discrete acts, which,

if taken before (he effective date of Title VII or outside

of the applicable statute of limitations, cannot be the

subject of a successful Title VII suit, even if the con

sequences of those actions continue to affect the employee

until the time of suit. Hut Title VII does require the

correction of unequal salaries that are the continuation

of racially-based pay differentials originating prc-Act or

in the time-barred period. This continuing salary dis

crimination is akin to intentionally discriminatory sen-

ority systems, which, regardless of the dale of their incep

tion, afford no justification for race-based disparate treat

ment.

I’liillips ilis.'ii'ieml with llic pmicl majority's l end I up of

Evans ami tliizchrimil an Mppliinblc to plaintitro’ (Hilary claims

(|<ct. App. 4l!!2n-1(>7a I . Those cases, he explained, do not permit

an employer to "continue practices now violative [of Title VIII

dimply because at one lime lliey were not” (Pel. App. 405a). In

his view, tin* Evans /JozWieood principle "simply has no loRienl

application” in cases involving "pay and oilier ‘condition of employ

ment’ claims, as opposed to hiring and other work-force composition

claims” (Pet. App. 400a).

13

11 .i >

.i We i t .

With regard to the statistical evidence, the court of

appeals articulated the correct rulis—that in a disparate

treatment ease challenging salary’,,(Ji^graices, plaintiff’s

statistical analysis must include i"variables which ought

to be reasonably viewed as determinants'of salary” (Pet.

App. 3t)la)—but improperly npplhkl that1 ride. The par

ties’ multiple regression analysed) lo^tillier with the other

evidence introduced, proved that! (hgre Was racial dis

crimination in salaries. None of the .variables omitted

from petitioners’ analyses undorniines 'that conclusion.

As a corollary to the “reasonableness” Standard for statis

tical proof, we urge (hat district coWls bo encouraged to

make formal determinations at the ea^'ligsl possible stage

'•rif if 1,r ii, (i Mini f llxk I'lelm-a in Vm itlplllilfwl

lical analyses offered at trial. \n •’,

Although private petitioners ask1 this Court, to consider

whether Title VII permits an employer to delegato its

hiring decisions to a third parly that invariably acts in

a discriminatory manner (85-93 Pet. 49-55), Ibis case

presents no such issue. It is clear that the Service was

jointly responsible with the county commissioners for the

selection of county chairmen; even the court of appeals

recognized this (Pet. App. 403a). The court’s reliance

on statistics relating to the recommendations made by re

spondents, rather than the final selection statistics, was

accordingly inappropriate.

Finally, the court of appeals correctly found that re

spondents had satisfied their affirmative duty to desegre

gate the 4-11 and homemaker extension clubs by main

taining and publicizing a policy of entirely open admis

sions to such clubs. Although some single-race clubs re

main, neither the Constitution nor Title VI requires any

particular degree of racial balance, and maintenance of

the traditional option of individuals to join any club that

they choose does not suggest that respondents are per

petuating their prior segregative practices.

M

ARGUMENT

f. IILACK STATE EMPLOYEES ESTABLISH A

CLAIM UNDER TITLI5 VII MY IDENTIFYING

CURRENT SALARY DISPARITIES BETWEEN

THEM SELVES AND WHITE EMPLOYEES HOLD

ING THE SAME JOIIS AND HEMONSTIIATINO

THAT SUCH IMSPAIUTIES RESULT FROM A

STATE POLICY IIEFORE 1905 OF PAYING

IILACKS LOWER SALARIES THAN WHITES.

The court of appeals acknowledged that, before the

merger in Ihe Service maintained two separate ra-

cially-segregaled hranches and paid black employees less

than white employees because of their race; that, after

the merger, these race-based disparities were not im

mediately eliminated; and that these disparities continued

after this suit was tiled and after Title VII became ap

plicable It* tlie Service in March 1072 (Pet. App. 35!)a-

3(50a, 385)a-35>Oa). As a result, since the effective date

of the Act, black employees hired before 15)05, because of

their race, have received and continue to receive lower

salaries than while employees who have been performing

the same job for Ihe same length of lime. The court of

appeals incorrectly decided that 'Title VII provides no

remedy to these black employees (Pel. App. 38fta-382a,

3!)Da-100a).

Thq court oT appeals relied in large part on this Court’s

decisions in United Air Dines, Inc. v. Evans, 431 U.S.

553 (15)77), and Hazelwood. School District V. United

States, 433 U.S. 20!) (1077), interpreting those decisions

as absolving an employer of any responsibility for af

firmatively eliminating the continuing effects of prc-Acl

salary discrimination provided il has adopted a race-

neutral policy in establishing salaries for posl-Act hires.

The appellate court’s reliance is misplaced, however, as

this Court’s decisions in Evans and Hazelwood are read

ily distinguishable from the case at bar.

In Evans, a female Might attendant forced to resign

when she married in 10(18, and rehired in 1072 after the

"no marriage” policy for female Might attendants was

i i t * 111 * 111 i

15 • l.. * . .1 i.

discontinued, challenged United’s refusal to credit her

prior service towards her seniorjjy. , looting the absence

of any allegation that prior service..is,credited to rehired

male employees under United’s, seniority system, this

Court acknowledged that the denial of pre-1072 seniority

"does indeed have a continuing Irtijtitct on 111',vans’| pay

and fringe benefits” (131 U.S. at 558), but rejected her

claim that United was guilty 6f a cdiitliiuing violation of

Title VII, staling (id. at 558, 5 (* 0 )1

• • - I • 11 • I. M I

|T1 he seniority system gives present effect to past

act of discrimination | the, forced resignation]. Hut

United was entitled to treat lliut past act as lawful

after respondent failed to file a charge of discrimi

nation within the f statu lory limitations period |. A

discriminatory act which is not made the basis for a

timely charge is the legal equivalent of a discrimina

tory act which occurred before the statute was

passed. It may constitute relevant background evi

dence in a proceeding in which the status of a cur

rent practice is at issue, but separately considered,

it is merely an unfortunate event in history which

has no present legal consequences.

« « • • •

'The statute does not foreclose attacks on Ihe current

operation of seniority systems which are subject to

challenge as discriminatory. But such a challenge to

a neutral system may not be predicated on the mere

fact that a past event which has no present legal

significance has affected the calculation of seniority

credit, even if the past event might at one time have

justified a valid claim agninst the employer.

The Court's decision in Evans thus turned on the fact

that United’s past act of discrimination—forcing Evans

In resign because she was a married female—was a sin

gle, discrete act taken at a lime outside of the applicable

statutory limitations period, and as such was not action

able under Title VII. 'The Court acknowledged, as the

court of appeals assumed here, that the Evans rule is

equally applicable when the discriminatory act was taken

before the effective dale of 'Title VII.

f

16

To similar effect is the Court’s decision in Hazelwood.

There this Court vacated a court of appeals judgment,

based on statistical disparities between the rncial compo

sition of Hazelwood’s leaching staff and that of the quali

fied public school teacher population in the relevant labor

market, that the school district had engaged in a pattern

and practice of hiring discrimination in violation of

Title VII. Although (his Court agreed that the court of

appeals correctly rejected the district courts statistical

analysis, it held that the statistical disparities on which

the appellate court relied were not dispositive ('133 U.S.

at 309-310 (footnote omitted)):

The Court id' Appeals totally disregarded the pos

sibility that this prima facie statistical proof in the

record might at the tidal level he rebutted by statis

tics dealing with Hazelwood’s hiring after it became

subject to Title VII. Racial discrimination by public

employers was not made illegal under Title VII un

til March ‘21, 1972. A public employer who from

that dale forward made all its employment decisions

in a wholly noiidiscriminalory way would not vio

late Title VII even if it had formerly maintained an

all-white work force by purposefully excluding Ne

groes. For this reason, the Court cautioned in the

Teamsters opinion \ International llrollicrhood of

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) 1

that once a prima facie case lias been established by

statistical workforce disparities, the employer must

be given *ui opportunity to show llutl the chinned

discriminatory pattern is a product of prc-Act hid

ing rather Ilian unlawful posl-Acl discrimination.’

431 U.S., at 360.

Thus, Hazelwood indicates that Title VII is not vio

lated by disparities in the racial composition of an em

ployer’s staff which are the present effects of discrimina

tory hiring decisions, all of which ocelli icd befoie the

effective dale of Title VII.

FJvans and Hazelwood thus establish that prc-Act or

lime-barred hiring and termination decisions cannot form

the basis of a claim under Title VII, even when those de

cisions have continuing current effects due, for example,

to I ho operation of a bona fide seniority system."' Simi

larly, prc-Act or time-barred qironiotiom decisions cannot

be challenged under Title V illon ilhe theory that the

claimant who should have1 I’e c e i • itlie- promotion now

continues in a lesser job at a> salaryi level below that

which he would have obtained' hndlhot not been the victim

of the pre-Act or lime-barred'-discrimination.” Hiring

and promotion decisions arc 'diset'ete1 acts, taken once and

for all at a single moment in Unite.< Evans and Hazelwood

teach that if that moment occurred prior to the effective

Section 70.1(h) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2 (h), validates

only "Itona lute” seniority systems. If nn employee ran show Hint

tiie seniority system was adopted with n discriminatory intent.

Section 70:t(h) affords llie employer no protection. 1‘idlmnn-

Standard v. Sivinl, 450 U.S. 27.1, 270-277 (1082). This Court has

emphasized Hint Section 70.1(h) “makes no distinction between

seniority systems adopted before its effective date and those adopted

after Its effective dale.” American Tobacco Co. v. l'oiternon, 450

U.S. 01, 70 (1082).

11 There appears to lie a mnllict among the circuits as to whether

nn employee can avoid a statute of limitations defense by establish

ing lie was denied promotion pursuant to a continuing practice

of discriminatory promotion denials, or whether lie must tile within

the statutory period after lie is himself dented promotion even where

such a practice Is alleged. Compare, e.g., Aclia V. Ilcnmc, 570 I'.2d

57, 05 (2d Cir. 1078) (continuously maintained promotion policy may

be subject of complaint until statutory time “after I lie fast occur

rence of an instance of that policy,” citing cases), and I'allernon

v. American Tobacco Co., 580 F.2d 800, 804 (41h Clr. 1078) iheann

is Inapplicable where a discriminatory promotion system is main

tained; the discrimination continues from day to day and a

specific violation occurs whenever a promotion is made), with, e.g.,

Human V. Town of Mount Vernon, 012 F.2d 074, 077-078 (5lh Cir.

1080) (suit must he filed within statutory lime after employee

should have perceived discrimination wns occurring). However, we

are unaware of any case In which u court has permitted an employee

to rely on the current effect of a discriminatory promotion policy

that was terminated In a lime-hnrred period. Such a complaint,

we submit, would clearly lie untenable under Feans. Moreover, we

have serious doubts about the validity of any theory that would

permit an employee who does not sue In n representative capacity

to recover when the denial of promotion that affected him is

wholly prc-Act or time-barred, even If the discriminatory policy

continues so as lo affeel other employees.

18

dale of llie Acl or beyond Hie reach of Hie statute of limi-

lations, llie discriminatory decision eamiol be the subject

of n Title VII anil, even though the consequences of that

decision may well continue to Hie present. Indeed, it

could scarcely be otherwise unless the Act is, as a prac

tical matter, to have retroactive application, and relief

for past illegalities is to be available into the indefinite

future. For heller or worse, unlawful discriminatory hir

ing, promotion and termination decisions must either be

timely complained of or be taken to iiave fixed a person s

situation once and for all—unless, of course, fresb illegal

ities nrc subsequently committed.

No such practical and conceptual difficulties attend the

correction of unequal salaries that are the continuation

of prc-Act, admittedly racially-based pay differentials.

One claim in the case at bar is that the Service has con

tinued to pay certain black employees less than while em

ployees holding the same job for the same length of time,

simply because of their race. Until now, the courts of

appeals—including the Fourth Circuit—have consistently

held that such discrimination in compensation is a con

tinuing violation of Title VII, and as such is actionable,

notwithstanding Kvans and Hazelwood, even when the

pay differentials originated before the elective dale of

the Act or outside of the statutory limitations period.

Thus, for example, the Fourth Circuit slated in Jenkins

V. Home Insurance Co., (!35 F.2d 310, 312 (1080) (per

curiam ):

Unlike Keans, (lie Company’s alleged discrimina

tory violation occurred in a series of separate hut

related acts throughout the course of Jenkins’ em

ployment. I'Ivory two weeks, Jenkins was paid for

the prior working period * * * an amount less than

was paid her male counterparts for the same work

covering the same period. Thus, the Company’s al

leged discrimination was manifested in a continuing

violation which ceased only at the end of Jenkins

employment.

Accord, Kim v. Coppin Slate ('allege, (5(52 F.2d 1055, 1001

(4th Cir. 1081) (“This court * * * has consistently dis-

I till . Will* l

19 , y lint o.

tinguished Keans when the (li^ i^ ijia lo ry employment

practice lias continuously affected . lj|c,.£|imphiining em

ployee and is continuing.” ) ; HalLjl.^(ulgx, Inc., 000 l1.2d

307, 308 (0th Cir. 1082) CTTJhei(discrimination was

continuing in nature. Hall suffq^ftl q,.denial of equal

pay with each check she rccoivejlf”^ V. ITT Finan

cial Corp., 010 F.2d 738, 743 ( g t y , ^ ^080) ("The prac

tice of paying discrinunatorily, upgquaj pay occurs not

only when an employer sets pay Jpvpls, ,\>ut as long as tho

discriminatory differential contin(^.”jl( j, [jarlcll v. Hcrlilz

School of Languages of America,t . 008 F.2d 1003,

1004 (Olh Cir.), cert, denied, 4(54 y.$f j)15 (1083) (“The

policy of paying lower wages lo,,ftma|q employees on each

payday constitutes a ‘continuing violation.’ ” ). Cf. I'erez

V. Laredo Junior College, 700 F.2d 731 (5th Cir. 1083)

(applying Title VII principles in suit under Sections 1081

and 1083).

Viewing discrimination in compensation as a continu

ing violation of Title VII, the courts of appeals after

Keans have held that pre-Act, intentional discrimination

cannot be used to justify llie post-Act payment of lower

salaries to minority employees than to other similarly

situated employees. In Lamplicre V. Ilrown University,

085 F.2d 743, 747 (1st Cir. 1082), for example, the First

Circuit ruled that a female faculty member’s “allegations

that she received a discriminatorily low wage after 1072

| when Title VII became applicable to educational institu

tions | as a result of pre-1072 discrimination” were ac

tionable, staling: “ |A | decision to hire an individual at

a discriminatorily low salary can, upon payment of each

subsequent pay check, continue to violate the employee’s

rights.” Cf. Ilcrry v. Hoard of Supervisors of Louisiana

Slate University, l i b F.2d 071, 080 (5th Cir. 1083). .

These court of appeals decisions refiect the proper con

struction oT Title VII, and correctly distinguish challenges

to salary discrimination originating before the Acl or out

side of the limitations period, but continuing after the

effective date of the Act, from cases such as Keans and

Hazelwood involving challenges to the post-Act effects of

J

20

discrete prc-Act decisions sucli as hiring and termination.

The continuing salary discrimination involved here is

akin to the continued use of an intentionally discrimina

tory seniority system, which this Court has held is unlaw

ful under Title; VII even if the seniority system was

adopted before the Act became effective. See I’ulliuan-

Stauilurd v. Swinl, inti U.S. 273, 270-277 (1082); Ameri

can Tobacco Co. v. Tall arson, 400 U.S. 03, 70 (1082).'"

Just as an intentionally discriminatory prc-Act seniority

system affords no justification for current employment

practices that have a race-based effect, so loo an inten

tionally discriminatory prc-Act salary system atfords no

justification for current salary practices that have a race-

based effect. To the extent that the court of appeals’

**“ of post-Act salary disparities as merely the

"lingering effect” of pre-Acl overt discrimination (I’et.

App. 300a) represents a willingness to tolerate such prac

tices, its decision cannot he allowed to stand.”

** Seo nolp ll>, nn/oo. Tills Court addressed llie <|ucsl!on of

continuing prc-Act salary disparities in the context of a suit under

tile Ri|unl Pay Act, 2!l II.S.C. 20(1; Coruiuij (ilonn IPorA*s v. Hrounon,

417 li.fi. I8R ( 11171). 1 list decision is not strictly In point hero,

however, as a violation of the Hipial Pay Act is established simply

by showing the payment of lower wages lo women than to men

performing llie. same work; the dale when the disparity originated,

nnd the reasons underlying the disparity, arc largely Irrelevant.

In contrast, the plaintiff in a discriminatory treatment case under

rillo VII must establish not only the disparity in wages, hut also

the employer’s inlcnl to discriminate. See Intornulioiml llrothcr-

hnod of Teamsters v. lluitrd Stolon, PI I tl.S. a t 3.75 n.lB. Thus,

a current disparity in salaries, without more, cannot he the basis

for this Title VII claim of discriminatory treatment. Instead,

It Is necessary to examine the basis for that disparity to determine

whether (here has been actionable intentional discrimination subject

lo a timely challenge. Here, although the Service’s decision lo pay

black employees less than whites for llie same work was taken

before Title V'll heroine applicable to public employers, there Is no

dispute that the Service's compensation scheme remained intention

ally discriminatory. See pages 7, It, sspn i ; Pel. App. 43!)n-440n;

Jf,A . i2n -t:to .

” Further fact finding will he necessary lo establish the recovery

due any individual employee. As both courts below emphnslzcd, the

I i

i

• in i .■ ii

21

V I I lilt

• 11 Hit’

I nil .0 1 ;

II. THE ItEDItESSION ANAEyt-fES.SHOWED IIACIAL

IMSCIII 111 I NATION, ANLMIESPONDENT.S Dill NOT

IIEl''IITI5 THAT SHOWING ...... •

.. i.i- i t "■

Tin; court, of itppnals clearly >yqt||d, have erred if it bad

held, as private petitioners assert .in their Questions Pre

sented, "that statistics may nob 'bd treated its probative

evidence of discrimination unless' tl)d'£Uilistical analysis

considers every conceivable npji-rAcjuil (variable” (85-83

Pet. i). However, the court /bftlQW.idid not impose this

onerous "every conceivable variable”, burden on petition

ers in this case. Halher the appellate' tout t articulated

the correct rule, that a plaintifTVMhtislical analyses in a

disparate treatment case m ust1 ihcliule "variables which

ought lo be reasonably viewed as determinants of salary"

(Pet. App. 31)la). We nevertheless agree with private

petitioners that the result reached by the court below

cannot be sustained because of a variety of errors of fact

and law.

It should be noted til the outset that reversal of the

court below on the first Question Presented automatically

requires reversal of (lie court of appeals’ analysis of the

statistical proof. One of the bases for the court’s rejec

tion of petitioners’ regression analysis in this case was

that “the analysis contained salary figures which reflect

the effect of pre-Acl discrimination” (Pet. App. 383a).

Hccause the result we urge on the first Question Pre

sented affirms the correctness of considering the effects

of the pre-Acl, salary discrimination in this case, the hold

ing of the court below cannot stand. At a minimum, the

case should tie remanded for consideration of whether,

when the effect of the pre-Act discrimination on salary

effects of Hie original discriminatory snlnry practices m o part of n

complex matrix of pro- ami poat-Act salary decisions, including

merit raises, cost of living increases, and county to •county varia

tions in salary increases ( I ’et. App. lOOn-llOa, !I(i0a-:t02a). The

extent to which these decisions carry forward the effects of 'the'

original discriminatory practices, nnd the extent to which any such

decision Is actionable in this suit by any employee, must lie resolved

flrsl by tile district court.

13113124

22

ia considered, llie petitioners’ statistics demonslrnle dis

parate treatment in fixing salaries.

Hut oilier factual and legal errors in Hie court of ap

peals’ analysis of the statistical proof in lliis case lcquiio

entry of judgment for tlie petitioners on (lie issue of

salary discrimination. Itefore discussing lliesc ciiois,

however, we outline the general standards for analyzing

the legal sufficiency or a plaintiff's regression analysis in

a disparate treatment pay disparity case. ”

A. In Order To list aid isli A I’llinn Facie Cnsc Of

Salary I Useriniiu:iI ion, A Regression Analysis Most

Control For Factors That Normally Atfccl Salary

Because this is a disparate treatment case, ” | pi roof of

discriminatory motive is critical” to a claim of class-

wide discrimination in fixing salaries. International

Brotherhood of Teantxle.ru v. United States, dill U.S. at

1135-330 n.15. But a plaintiff is not required to prove

discriminatory motive directly. A plaintiff establishes a

primn facie case ol intentional racial disci iinination un

der Title VII if be "eliminates the most common nondis-

criminatory reasons” for the challenged act. t exas De

partment of Community Affairs v. Iturdine, 450 U.S.

248, 254 (1081). The reasoning underlying this standard

was explained in Furtteo Construction Tory. V. Watci s,

438 U.S. 507, 577 (1078) (emphasis in original):

fW]e arc willing to presume 1 intentional discrimina

tion 1 largely because we know from our experience

that more often Ilian not peojde do not act in a

totally arbitrary manner, without any underlying

reasons, especially in a business setting. Thus, when

all legitimate reasons for rejecting an application

have been eliminated as possible reasons for the em

ployer’s actions, it is more likely than not the em-

2* Our discussion focuses on llie use of one typo of stalisticnt

evidence: multiple egression analyses. A party may offer other

types of statistics, such as cohort studies and multiple pool tests,

cither Instead of or .........ion to regression analyses. We do not

suggest tha t regression analyses are the only, or even the best,

statistical loots for use in disparate treatment cases.

23

.. nil y jut ml '

l-nily lu\v x

ploycr, who we generally assumeiffcts onty with some

reason’, based his decision on an.linipormissiblo con

sideration such as race. ■ ' i. i,i hit.

When plaint iffs present their proof 'in 'the form of sta

tistical analyses, these basic principled'should not change.

Statistical methods should continue'to'reflect the prem

ises that in a disparate treatmenB cKW iffrti'ntiff claims

to be the victim of intentional discrimination, and that

plaintiff bears the burden of proviHg Wih't intention.

Statistics arc just a way of proving intenlidn by indirect,

inferential means. The touchstone df"'whethcr plaintiff

lias made out a prima facie case (that'is, whethci plain

tiff has made a showing sufficient to1 permit the case to

he presented to the trier or fact) is whether bis statis

tical analysis eliminates the “most common nondisci iin-

iualory reasons” for the disparate treatment, thus leav

ing racial discrimination as the logical inference. In

order to apply these principles to statistical proof in a

disparate treatment ease, however, it is essential to

understand the probative value of the statistics. As this

Court admonished in Teamsters: ‘| S I tatistics . . . come

in infinite variety . . . . |T |heir usefulness depends on all

of the surrounding facts and circumstances.’ 431 U.S.,

at 340.” Hazelwood School District V. United States, 433

U.S. at 312.

In this case the primary statistical proof offered by

the United States on behalf of the plaintiffs consisted of

multiple regression analyses. The purpose of a multiple

regression analysis in this setting is to determine whether

the factor of race has sufficient correlation to salary

differentials lo satisfy plaintiff’s burden of proving in

tentional discrimination. In the language of statistics,

salary is referred to as the “dependent variable” in the

calculation. To make the calculation “one first specifies

the major variables | referred to as ‘independent vari

ables’! that are believed lo influence the dependent vari

able.” Fisher, Multiple degression in Legal Proceedings,

80 Colum. 1/. Itev. 702, 705 (1080). “The relationship

between the dependent variable [here, salary) and the

24

independent variable nr in te re st I here, race] is then esti

m ated by ex trac tin g Hie effect* of the o ther m ajor v an -

nbles” (id a t 70(1). “ 'I’hc resu lts of m ultiple regressions

can be read as showing the effects or each variable on

the dependent variable, holding the others constant,

Moreover, those resu lts allow one to make statem ents

about the probability th a t the effect described has merely

been observed as a resu lt of chance fluctuation 0 * •

Thus in order to show that race is likely to have in

fluenced salary, a multiple regression analysis must con

trol for other major variables that are thought to influ

ence salary. A multiple regression analysis that is so

structured can meet the plaintiff’s burden of proving a

prima facie case of disparate treatment because the sta

tistical proof eliminates the "most commoni nondiscrini-

inatory reasons" for the disparate treatment.

Conversely, if the plaintiff’s multiple regression analy

sis does not account statistically for the “most common

nondiscriminatory reasons” for differences in salary, the

statistics cannot he said to give rise to an inference of

racial discrimination and therefore do not make out a

prima facie case. This principle was recognized in the

context of hiring discrimination in Hazelwood School

District v. United Slate*, 433 U.S. at 308. The Court

held in that case that in order to show racial discrimina

tion in hiring school teachers the “proper Islatislical|

comparison was between the racial composition of Hazel-,

wood’s teaching staff and the racial composition of the

qualified public school teacher population in the relevant

labor market” lihid.; emphasis added). The Court went

on to explain Unit the statistical analysis must account

21 In mlilitiim, or course, llie multiple regression nmdysis ""ih1

Imve Hlnlistic»l reliability. “ I A | regression not only estimates tl«e

rlTecln of llie variables involved in Ilic mo.lcl but also niensunw

llie certninly or nccnracy of such eslinmtes. In mldillon. It |»rovl.l.H

' oven.ll measnres of how well the mo,lei Ills I be data ns n whole

Fisher, nupra. HO Colon,. I,. Itev. at 710. The s t a t i s t i c slgnincance

of the petitioners’ repression analyses was not questioned by the

courts below ami is not an issue in Ibis rase.

i ‘

i ♦

ti . m.ilv

25 1 .'l u v li. ,

for hiring qualiflcations in order to Wav^prob'ative value

(id. at 308 n .l3):

In Teamsters, the <cmq>arkjpn ^cl^eeu the per

centage of Negroes on I be employer^ work force and

the percentage in the general areawide population

was highly probative, because the Joli skill (here in

volved—the ability lo drive A1 tfbek^ift one that

many persons possess or can fairly readily acquire.

When special qualifications afe r^qiiNd to fill par

ticular jobs, comparisons to the, gcnerhl, population

(rather than to the smaller grpjip fit individuals who

possess the necessary qualifications), .mgy have little

probative value. '

It follows from llie Hazelwood Court'd'ft'rittlysis, and a

number of cases have so held," that in a disparate lieat-

ment case ir a plaintiff’s statistics fail to account for the

"most common nondiscriminatory reasons’ for the em

ployer’s behavior (Burdinc, 450 U.S. at 254) (that is, if

they do not account for “variables which ought to be

reasonably viewed as determinants of salary (1 oL App.

301a), the defendant may prevail merely by pointing

out that plaintiff’s proof is not sufllcient to give rise to

an inference of discrimination. In those circumstances

it should not be necessary for the employer to offer his

own statistics in rebuttal.M

22 Si>c, e . iV u lc i i l i iw v. U.S. I'nslal Service, 074 F.2,1 r.r., 70-71

( l )C Cir 1082); ICnstlaml v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 704 l' 2,l

613 024-025 ( l l t l , Cir. 1083); Wilkins V. University of Houston,

054 F.2,1 388. 401-405 (Bill Cir. 1981); cf. St. Marie v. 1C os tern

ti ll. /Is.i ' ii. 050 F.2,1 305, 400 (2d Cir. 1081).

MSome enses have Indicated IImt an employer cannot challenge

a plaintilf’H statistical evidence with,ml making a showing that the

factor llie employer clainiM all,mid have been Included in tlm plain-

tllfq analysis would in fact have eliminated the racial effect. Seyar

V. Smith, 738 F.2,1 1240, 1207-1270 (D.C. Cir. 1084), cert, denied.

No. 84-1200 (May 20, 1085); Trout v. Lehman, 702 F.2,1 1004,^1102

fl) C Cir HNW), rcv'il nil oilier grounds, 465 U.S. 1056

cf (irifjin v. Carlin, 755 F.2,1 1510, 1520-1528 (1111, (hr. 1085).

These cases rely on Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 300-302. for the relevant

pattern of proof In class disparate treatment cases. Hut be

of proof In Teamsters docs not differ signiflcanlly from that staled

20

This is not. to s:iy that the plaintilT as part of his ,

prima facie case must present a perfect statistical analy

sis which Lakes into account every conceivably relevant

variable. Dolliai d V. Itawlinson, '103 U.S. 321, 331

(15)77). Indeed, statistical theory presumes that even

after the multiple regression analysis accounts for all

the major factors thought to influence the dependent

variable, other factors remain unaccounted for, and these

factors may have a significant influence on the dependent

variable. Fisher, Hit pm, 80 Colmn. L. ltcv. at 705-700.

If the plaintiff’s statistics include the major non-discrim-

Inatory factors thought to influence salary, and if they

show a statistically significant effect for race as a de

pendent variable, the plaintiff has made the required

prima facie showing of disparate treatment. If at that

point the defendant asserts that some additional factor

should have been accounted for in the regression, the

defendant must show that inclusion of the factor would

have explained the salary disparity (that is, that inclu

sion of the factor would, have eliminated the statistically

significant effect for race). Requiring the defendant to

offer statistical for other) proof at this stage is consist

ent with the requirements of McDonnell Douglas Carp.

v. Green, d ll U.S. 75)2, 302 ( 15)73). To dispel the

adverse inference from a prima facie showing the em

ployer must "articulate some legitimate, nondiscrimina-

lory reason for the employee’s rejection.” Ibid. Accord

Furnco, 428 U.S. at 578.

As stated above, we believe that the court of appeals

in (his case articulated the correct standard, requiring

the plaintiff’s statistics in a disparate treatment case lo

include "variables which ought to be reasonably viewed

as determinants of salary” (l’cf. App. H!)la). Ibis rule

of reason, like all general evidentiary standards, par-

in lluriliiie. Iinloctl Trunutlcrs explicitly mloimvlcdacs Hint the

employer may nllncli the plnlntiH'n nine by Rhmvinu Hint plninlill's

proof is "iiuiceiirnle or iiiHi|-iiill'':inl” ns well ns by "prnvhlf iii({I n

iioiiillMcriiiiinsloiy r\plminlion for Hie nppniciilly tllscrliiiinnloiy

result’’ (431 U . H . nl Slid-IMil & n.t(i).

A

iiculnrly those relating lo slalisfftaf j)Wbf, will neces

sarily vary in application from cadti W Owe.' Sec Hazel

wood, 433 U.S. at 312; Tcainslcrd,'A$\' V & at 310. In

many situations, common sense wfll*'Vltel*?’'obvimia an

swers. In this case, for example,’ i f WHlr'iWnablc to

expect that the length of time the''6mj)loybrJ worked for

the defendant (job tenure) would employees

salary, because some of the pay raifteB tlle"dihploycr gave

were across-the-board percentage ' Incl'feusdsh Therefore

the slalislics offered by the United SlilleA bn behalf of

the plaintiffs in this case did include jWl Tenure as a

variable in flic multiple regression analysis.

In general the “variables which ought to lie reason

ably viewed as determinants of salary” sfioUld reflect the

factors that go into the employer’s own salary decisions

In a disparate treatment case it is assumed that an

employer is not required to make hiring, promotion o.

salary decisions on a basis common lo most employers,

or on any given basis. Title VII requires only that the

basis or decision be nomliscriminatory. Ihndine, 450

U.S. at, 258-255); St. Marie v. Eastern It.R. Ass'v, 050

F.2d 305, 30!) (2d Uir. 1081). Thus, for example, \( the

defendant chooses lo give raises on the basis of job atten

dance, the plaintiffs’ regression analysis should include

job attendance as a variable.1'

In disparate treatment cases where the parties dispute

whether a particular factor or variable "ought^ to be

reasonably viewed as |a l determinantM salary (l et.

App. 3!)la), if that dispute is not resolved before trial,

one party or the other may be seriously disadvantaged

by the trial court’s ruling on that issue. If plaintiff's

regression does not account for the variable and the dis

trict court rules that its inclusion was required as part

of plaintiff’s prima facie case, plaintiff will lose unless

si In lliin hypothetical, if Ibi; plaintiff wan i«lb-»-iiur Hint job

ntlemlniico lecm.ls bail boon kepi In a illscrliniiintory fashion,

plninliir’a icgniH.qion nnnlymH need not include thin "limited vnri-

able, .10 four; .1.1 plninlHf olToro.l some proof that nllcn.lnticc reconla

wero tninleil by racial illsci iiiiiiinlioii. See note 34, infra.

1I

28

lie bus prepared back-up statistics. Conversely, if the

district court rules Hint Hie variable was not required

to be included, a defendant who bad been relying on tbe

inadequacy or plaintiffs case will lose if be bad not

prepared counter-statistics. Hut these barsli results are

not inevitable. A preliminary judicial determination of

the nondiscriminatory factors Unit arc to be subjected

to analysis will greatly aid in eliminating evidentialy

nnd burden of proof problems because it will focus Hie

court’s and the parlies’ efforts on tbe same data from

tbe outset. This approach will preclude wasted efforts

(an important consideration because of Hie exceptional

time and expense involved in preparing multiple regres

sion analyses) and post hoc reallocation of bin dens. \Ve

therefore urge, as a corrollary to tbe reasonableness

standard we have outlined, that district courts be en

couraged to make formal determinations at the earliest

possible stage of proceedings as to tbe required (for tbe

plaintiff) and permissible (for tbe defendant) data to be

Included in multiple regression analysis offered at trial.

See Finkclstein, degression Models in Administrative

Proceedings, 8(1 llarv. L. Ucv. 1442 (1973).

II. The ('m ill Of A|i|icnls Hired In Analyzing The

Hliilisliciil Proof Offered In This (’use

The allocation of proof outlined in tbe preceding sec

tion docs not place excessive burdens on plaintiffs in dis

parate treatment cases. Indeed, application of these

standards to the facts or this case compels the conclusion

that the multiple regression analyses employed on behalf

of petitioners, in conjunction with the other evidence

introduced, proved racial discrimination in salaries.'55

Although the nondiscriminatory variables on which the

courts below focused are generally ones that should be

2" We submit Unit pel it loners eslnblishcd n prlmn fnelc disc; Unit

1 tho Service did not successfully produce probative rebutting evi

dence; nnd that tin- petitioners therefore sustained llieir burden of

persuasion In accordance with thii ln l Stales fo i l 'd Service Hoard

, of Governors v. Min us, ICO U.S. 711 (I!I8H>. we now focus oil tbe

evidence ns a whole.

2!)

considered in an analysis of salary, f̂ he jipurts cited in

their examination of these factors in |t)jQ,particulai cii-

cuinslances of Ibis case. •' ' ,u"

The United .Slates’ expert prepaid multiple regres

sion analyses concerning salaries for.Iilie .years 1871, 1.175

and 1(181. Certain of these regressiAns usdrl four inde

pendent variables—race, education,1 Whyil‘6; hlld job title.

This model reflected the deposition .leijtjmqjjy, of a Service

official who staled that the most important, feelers in de

termining salaries were tenure, job title*' education de

gree and job performance (see page 5,' sliprH)'; Hie model

omitted only Hie factor of job perfoHVuihcci which was

accounted for by other evidence itj' Ihe 'pase.2'' The re

gressions showed that in 1074 the average black em

ployee earned $331 less Ilian a while employee with Ibo

same job lille, education and tenure (C.A. App. 1501,

402-403), and that in 1975 the disparity was $395 (C.A.

App. 1589, 4Hi).*21 Holli of (hose racial disparities were

statistically significant (C.A. App. 402-403, 4 Hi).-'"

The Service introduced multiple regression analyses

prepared by its expert for the years 1975 and 1981.

Using Hie same model that Hie petitioners had used, re

spondents’ expert obtained substantially the same result

for 1975, a statistically significant racial effect of $384

2,1 Sec pages !I2-!I'1, infra.

21 Contrary h> the district min i's suggestion (Pet. App. ISlin-

I;)i).,), | | , e Inclusion of county cluiirincn in the ilaln Imse iliil not

distort the results of these regressions. Job title wns included ns n

vnrlnble in the erllienl regressions, nnd therefore the snlnries of

county chairmen were only compared with those of other county

chairmen—nnd the salary claims related only to the salaries or

agents.

“ The regressions for I'.IRI showed n smaller disparity which

lacked slnlistlcal significance (C.A. App. 1I>7R). The lack of a

significant racial disparity it, 1U8I affects, at most, the relief In

which plaint Ilfs are entitled; it does nut affect the Service's tinbililn