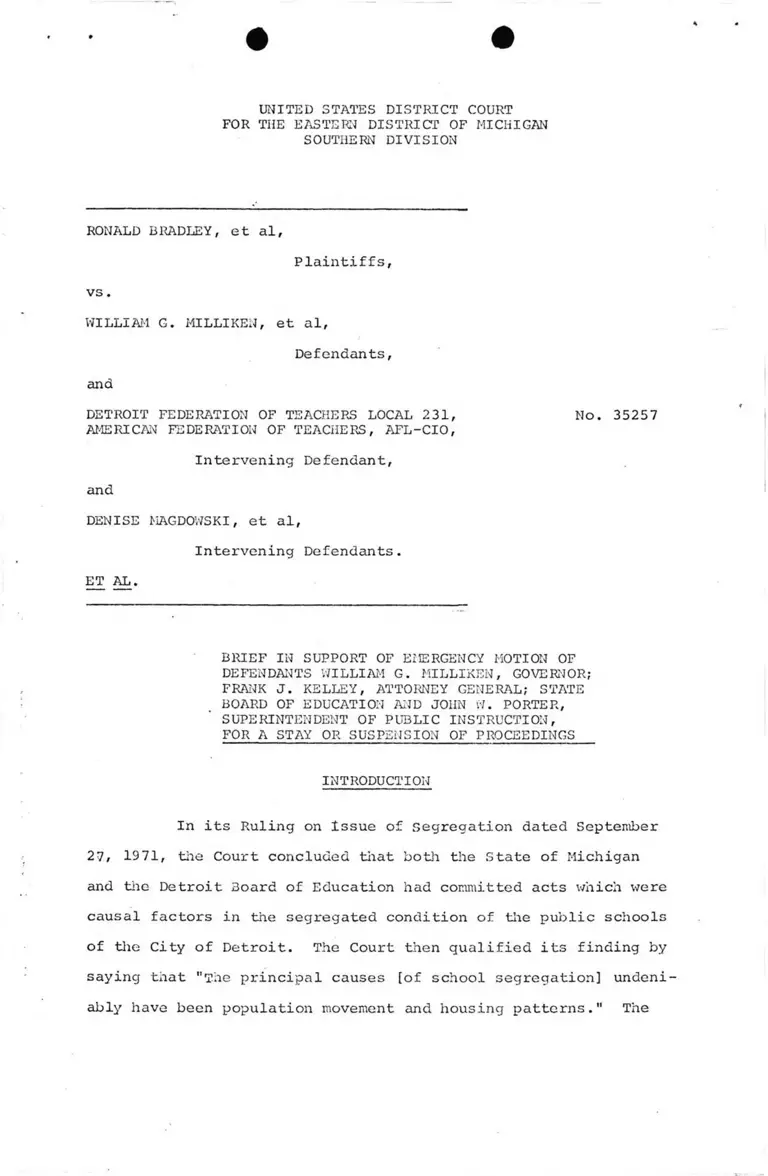

Brief in Support of Emergency Motion of Defendents For a Stay or Suspension of Proceedings

Public Court Documents

June 19, 1972

16 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Brief in Support of Emergency Motion of Defendents For a Stay or Suspension of Proceedings, 1972. 22f2ab43-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/06955deb-9f6f-4955-8564-d73d461bdfc3/brief-in-support-of-emergency-motion-of-defendents-for-a-stay-or-suspension-of-proceedings. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.

Plaintiffs,

vs.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al,

Defendants,

and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS LOCAL 231, No. 35257

AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Intervening Defendant,

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al,

Intervening Defendants.

ET AL.

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF EMERGENCY MOTION OF

DEFENDANTS WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, GOVERNOR;

FRANK J. KELLEY, ATTORNEY GENERAL; STATE

BOARD OF EDUCATION AND JOHN W. PORTER,

' SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION,

FOR A STAY OR SUSPENSION OF PROCEEDINGS

INTRODUCTION

In its Ruling on Issue of segregation dated September

27, 1971, the Court concluded that both the State of Michigan

and the Detroit Board of Education had committed acts which were

causal factors in the segregated condition of the public schools

of the City of Detroit. The Court then qualified its finding by

saying that "The principal causes [of school segregation] undeni

ably have been population movement and housing patterns. The

Court then requalified this conclusion by adding, "but state

and local governmental actions, including school board actions,

have played a substantial role in promoting segregation."

Since the State of Michigan is not a party to this

suit, the references to the State of Michigan and state govern

mental actions, if they have any bearing, must have been

references to the Governor, the Attorney General, State Board

of Education and the Superintendent of Public Instruction,

the named defendant state officers.

In its Ruling the Court outlined the principals

essential to a finding of de jure segregation, as follows:

1. The State through its officers and agencies, and

usually the school administration, must have taken some action

or actions with-a purpose of segregation.

2. This action or these actions must have created or

aggravated segregation in the schools in question.

3. A current condition of segregation exists.

In the Ruling there is no finding that either the

Governor or the Attorney General had committed any act that was

a contributing factor in the alleged segregated condition of

the Detroit Public Schools. Although in its Ruling the Court

cited Const. 1963, Article I, Section 2 and Article VIII, Sec

tion 2, neither of these constitutional provisions imposes any

duties upon the Governor or the Attorney General with regard to

either housing or education.

Neither the Superintendent of Public Instruction nor

the State Board of Education have any duties under the constitu

tion or laws of tire State of Michigan with regard to housing.

-2-

O n e evidentiary finding against the State Board of Education

was that it issued a joint policy statement with the Michigan

Civil Rights Commission under date of April 23, 1966. In this

statement, the State Board of Education pledged itself to prevent

and to eliminate segregation of children and staff on account of

race or color "in programs administered, supervised or controlled"

by it. There is no finding that any program administered, super

vised or controlled by the State Board of Education was segregated

on account of race or color. The sole finding of the Court with

regard to the joint policy statement is the language "[L]ocal

school boards must consider the factor of racial balance along with

other educational considerations in making decisions about selec

tion of new school sites, expansion of present facilities...Each

of these situations presents an opportunity for integration."

Clearly, the statement itself is not discriminatory. It is no

more than a recommendation to local boards of education that they

"consider" the factor of racial balance. It is impossible to

see that the making of such a statement could be a causal factor

in the segregated condition alleged to exist in the Detroit

schools.

The other finding against the State Board of Education

is the statement found in the Board's "School Plant Planning

Handbook." It recommends "[c]are in site location... if a serious

transportation problem exists or if housing patterns in an area

would result in a school largely segregated on racial, ethnic or

socio-economic lines." The statement itself is not claimed to

be discriminatory. The power of site selection is vested in

boards of education of local school districts. This statement

is no more than a recommendation to local boards of education

to use care in site selection. It is impossible to see how such

-3-

a recommendation could be a causal factor in the alleged segrega

tion within the Detroit public schools.

The Court's Ruling on Desegregation Ẑ rea and Order for Develop

ment of Plan of Desegregation is predicated upon its Ruling that

"illegal segregation exists in the public schools of the City of

Detroit as a result of a course of conduct on the part of the State

of Michigan and the Detroit Board of Education." The findings

recited above are the sole basis for the Court’s razing 53 school

districts established under the laws of the State of Michigan and for

changing the schools, the teachers, the programs and, in fact, the

entire educational system for 1/3 of the public pupils in the State

of Michigan.

Moreover, the Court's rulings upon de jure segregation because

of actions of the Detroit School District are not only inconsistent

but equally unsound. The high praise that this Court heaped upon the

defendant Detroit for integrating its faculty and administrators has

been swept away by the Order of June 14, 1972 requiring racial balance

of at least 10% of black faculty in every school within the 53 school

districts, in direct disregard of Swann v Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 402 US 1 (1971). Assuming arguendo that the Court is

correct in its rulings as to actions of the Detroit School District,

at best, a remedy requiring correction within the school district is

all that is presently judicially mandated under Keyes v School District

No, 1, Denver, Colorado, 445 F2d 990 (CA 10, 1971), cert granted 404

US 1036 (Jan. 17, 1972). This is especially true in light of the recent

reversal of Bradley v School Board of City of Richmond, Virginia,

__ F.2d___ (CA4, June 5, 1972), Case No. 72-1058 to 72-1060 and 72-1150,

so heavily relied upon by this Court in its Ruling on Propriety of

Considering a Metropolitan Remedy to Accomplish Desegregation of the

Public Schools of the City of Detroit of March 24, 1972, but con

spicuously absent from the Court's Ruling and Order of June 14, 1972.

-4-

I.

THIS COURT SHOULD, IN THE EXERCISE

OF ITS SOUND DISCRETION, GRANT STATE

DEFENDANTS' MOTION FOR STAY OR .

SUSPENSION OF THIS COURT'S ORDER

OF JUNE 14, .19 72.___________________

The authority for this Court's granting a stay of its

mandatory injunctive order of June 14, 1972, pending appeal is

contained in FR CivP62(c). This Court also has the authority under

28 USC 2101(f) to grant a stay pending the disposition of the

state defendants' petition for a writ of certiorari. In each

instance the grant or denial of a stay is reposed in the sound

discretion of the court. The state defendants, for the reasons

set forth below, respectfully urge this Court in the exercise of

its sound discretion, to grant their motion for a stay or suspen

sion of the order entered herein on June 14, 1972.

In determining whether a stay should be granted, courts

consider several factors. These factors include the probability

of reversal on appeal, whether the denial of a stay will result

in irreparable injury to the party seeking same, whether the grant

ing of a stay will substantially harm the interests of the other

parties, and finally whether a stay is in the public interest.

Long v Robinson, 432 F 2d 977 (CA 4, 1970); Belcher v Birmingham

Trust National Bank, 395 F 2d 685 (CA 5, 1968).

In Bradley v School Board of City of Richmond, Virginia,

___ F 2 d ___ (Case Nos 72-1058 to 72-1060 and 72-1150, June 5,

1972) the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit reversed a

decision of the trial court granting a remedy substantially

similar to that contained in this Court's order of June 14, 1972.

In that case the court directed a metropolitan remedy only after

a trial involving the adjoining school districts which resulted

-5-

in a finding of de_ jure segregation as to such school districts.

Here, as stated by the Court in its opinion of June 14, 1972,

there has been no conclusion concerning either the establishment

of the boundaries of the affected school districts .or the conduct

of the 52 suburban school districts with respect to acts of de

jure segregation. In addition this Court, after expressly finding

no de jure segregation as to faculty and staff in the Detroit

public schools, has ordered that 10% of the faculty and staff

in each school be black. Thus contrary to the explicite language

of Swann v Charlotte-Hecklenburg Board of Education, 402 US 1,

16,24 (1971), reh den 403 US 912 (1971), this Court, in the

absence of any finding of a constitutional violation as to

faculty and staff has decreed an impermissible fixed racial

balance for each school within the 53 school districts.

In view of the foregoing it is urged that this Court's

order of June 14, 1972, extends beyond any existing federal

appellate precedent in, school desegregation cases. Thus

clearly there exists a substantial probability that this Court

will be reversed on appeal.

Turning to the question of irreparable injury it is

manifest that the implementation of this Court's desegregation

decree in the Fall, 1972 term without full and final appellate

review and the probability of reversal on appeal will result in

irreparable injury to the state defendants and the people of the

State of Michigan. The Court's order contemplates, as an

irreducible minimum, K-6 implementation by the Fall, 1972

term along with faculty and staff desegregation. This will

subject students, parents, teachers and administrators to the

trauma of reassignment with the distinct probability of further

reassignment as a result of reversal on appeal.

6-

The Order of June 14, 1972 from which Stay is

respectfully requested commands your defendants to pay the costs

of the panel and to provide funds to insure that local officials

cooperate fully. Further, they are mandated to "take immediate .

action," among others, to establish in-service training of faculty

and staff, and to employ black counselors.

Your defendants possess no power under state law to

hire black counselors. Defendants Milliken and Kelley have no

powers whatever under state law in the area of education. Simply

put, tiie state defendants do not possess the power of the purse.it

Under Michigan .law/is reposed in the Michigan Legislature.

Const 1963, art 4, § 30:

"The assent of two-thirds of the members

elected to and serving in each house of

the legislature shall be required for the

appropriation of public money or property

for local or private purposes."

Const 1963, art 9, § 17:

"No money shall be paid out of the state treasury

except in pursuance of appropriations made by law. "

Your defendants have no authority to expend funds without legislative

approval and the legislature is not a party to this cause.

The school year 1971-72 is over. Teachers and other

teaching school staff have left for their vacations or have embarked

upon studies. Assuming that they could be reassembled and the time

limits appear to make this not only impracticable but impossible,

if these public funds are expended by your defendants and the Orders

of this Court are reversed upon appeal, they will never be recovered

to the loss and detriment of the people of this State.

-6 a-

In addition this Court's remedial injunctive order

disrupts the education programs of 53 school districts, educat

ing approximately 800,000 or 1/3 of the students in this state.

Further this Court.'s remedial order requires the rearrangement

of the financial, contractual and administrative aspects of 53

separate school districts. Consequently a reversal on appeal

will necessitate the re-establishing of such financial, adminis

trative and contractual relationships. Clearly, the process of

implementation of this Court's remedy, prior to full and final

appellate review, will only serve to engender chaos and confusion

should this Court's remedial decree be subsequently overturned

on appeal.

A remedy of the scope and magnitude decreed herein,

involving 18 school districts that are not parties to this

litigation should not be undertaken prior to appellate review

of the caiclusias and findings of de jure segregation and the

propriety.of the metropolitan remedy. To do otherwise is to

disregard the important aspects of stability and continuity in

this state's educational system.

Moreover the development and implementation of this

Court's judicially decreed remedy will necessitate the expenditure

of substantial sums of state funds. These funds may not be

recaptured even though this Court's remedial injunctive order may

subsequently be overturned on appeal.

To summarize this aspect of state defendants argument

it is simply untenable to implement this Court's remedial decree,

broader in magnitude and scope than any remedial decree ever

handed down in a school desegregation case in the absence of

prior appellate review. Here it must be emphasized that in the

-7-

Richmond case, supra, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals granted

a stay of implementation of the lower court's remedial decree

pending appeal.

It may not be argued that the granting of a stay herein

will result in substantial harm to the plaintiffs. This case

was filed less than two years ago. A substantial portion of the

intervening period was consumed by plaintiffs' attempts to secure

preliminary injunctive relief both from this Court and the United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit on two separate

occasions. Thus it cannot be said that there has been any undue

delay in the effectuation of plaintiffs' constitutional rights

in this cause.

This Court's injunctive order of June 14, 1972, already

recognizes that for certain grade levels it is simply not

practicable to implement desegregation in the Fall, 1972 term.

Thus it cannot be reasonably maintained that the grant of a

stay pending appeal will result in substantial harm to plaintiffs

herein.

There is sound precedential authority, based upon the

decisions of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit, in Davis v School District of the City of Pontiac Inc,

309 F Supp 734 (ED Mich, 1970), aff’d 443 F 2d 573 (CA 6, 1971),

order #20,477, June 3, 1970; Uorthcross v Board of Education of

City of Memphis, 312 F Supp 1150 (WD Tenn, 1970), order Misc.

1576, June 2, 1972, for the granting of a stay pending appeal.

(The orders granting stays in these two cases are attached

hereto as Appendix A and Appendix B, respectively.) In the

Davis case, supra, the court squarely concluded that denial

of a stay could result in irreparable injury to the defendants

-8-

and that the granting of a stay would not result in irreparable

injury to the plaintiffs. That case involved a remedial decree

involving one Michigan school district. This case, involving

53 separate Michigan school districts and some 800,000 pupils,

is clearly a much more compelling case for the granting of a

stay pending appeal. In contrast to Davis, supra, this case

involves, the metropolitan reassignment of teachers and new

interim and f i n a l arrangements for 53 school districts

concerning finances, hiring practices, curriculum, inservice

training of staff, and administrative and governance aspects

of school operation.

In Davis, supra, the court concluded that the grant

of a stay was in the public interest. Consequently the conclu

sion is compelled that the grant of a stay in this cause is even

more so in the public interest of the people of the State of

Michigan. The affected students, parents, teachers and adminis

trators, stripped of their ability to know what school they will

attend or work in come fall and as to teachers and administrators

now bereft of their contractual rights, necessitate the granting

of a stay herein.

In addition one recognized function of a stay pending

appeal is to preserve the status quo. Pettway v American Cast

Iron Pipe Co, 411 F 2d 998 (CA 5, 1969), reh den 415 F 2d 1376

(CA 5, 1969). This cause, involving the most sweeping decree

to date handed down in a school desegregation case, is certainly

the perfect illustration of a case in which a stay should be

granted preserving the status quo pending appeal. The trauma

of reassignment, subject to probability of further reassignment

in tiie event this Court's order is overturned on appeal, mani

festly warrants the granting of a stay. This Court's order of

-9-

June 14, 1972, with its provision for a 9 member panel to work

out the mechanics of interim and final plans and its provision

for recommendations by the Superintendent of Public Instruction

as to interim and final arrangements covering the whole range

of school district operations, vividly illustrates the many and

complex problems inherent in this Court's remedial decree.

State defendants respectfully submit that such a massive under

taking should not commence prior to the prompt appellate review

that the state defendants have consistently sought in this cause.

One additional ground for the granting of a stay is the

pendency of a case in the United States Supreme Court which, when

decided, will settle many of the questions involved in the case

in which a stay is granted. Blue Gem Dresses v Fashion Originators

Guild of America, 116 F 2d 142 (CA 2, 1940). Currently pending

in the United States Supreme Court is Keyes v School District No.

1/ Denver, Colorado, 445 F 2d 990 (CA 10, 1971), cert granted 404

US 1036 (Jan 17, 1972) . Further, undoubtedly the decision of the

Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond, supra, is also cer

tain to be reviewed by the United States Supreme Court. The

resolution of -those cases by the United States Supreme Court

will undoubtedly settle many, if not all, of the questions involved

in tne instant cause.

In this regard, it should be stressed that there is

-10-

presently pending in the United States Supreme Court petition

for writ of certiorari entitled Milliken, et al v Bradley, et al,

October Term, 1971, No. 71-1463, in which request is made of

the nation's highest court to take this case and review the

basic decisions of the District Court that the Detroit school

district is a de jure segregated school because of actions of your

defendants and that a metropolitan remedy is appropriate where the

district court did not even consider and makes no finding that

neighboring school districts are de jure segregated or the

boundaries of such 52 school districts were established to create

or maintain de jure segregation. The Clerk of the United States

Supreme Court has advised your defendants that their petition for

certiorari will be submitted to the Court for its action during

the pres exit term.

Thus, a stay order should issue because of the possibility

the United States Supreme Court will grant your defendants'

petition for a writ of certioari, given the urgent and unique

nature of this case. The Court has the authority to grant such

an order under 28 USC 2101(f). This is most important because the

granting of a writ of certioari is an automatic stay of the lower

court order. Click v Ballentine Produce, Inc?, 397 F2d 590, 594 (CA 8,

1968); United States v Eisner, 323 F2d 38, 42 (CA 6, 1963), reversed

on other grounds, 329 F2d 410 (CA 6, 1964).

-10a-

SUMMARY

The State of Michigan is not a party to this action.

Defendants Milliken, Kelley, State Board of Education and Porter

are parties to this action. Based upon a record that shows:

1. Defendant Milliken pursuant to a constitutional duty

imposed upon him by Mich Const art 4, § 33, approved

1970 PA 48. Under its provisions he appointed a

first class school district boundary commission. He

is an ex-officio member, without vote, of Defendant

State Board of Education;

2. Defendant Kelley rendered legal opinions as required

by law. MCLA 14.32; MSA 3.185;

3. Defendant State Board of Education adopted a joint

policy statement v/ith the Michigan Civil Rights

Commission encouraging voluntary consideration of

racial balance in location of school buildings and

in the area of school construction published a hand

book recommending care in site selection if housing

patterns would result in segregation on racial,

ethnic or socio-economic grounds; and

4. Defendant Porter is the Superintendent of Public

Instruction and Chairman of the State Board of

Education <■

this Court found that your defendants have taken actions with the

purpose of segregation and these actions must have created or

aggravated segregation in the Detroit Public School District.

11

Over the continuing objections of your defendants, this

Court permitted evidence to show discrimination in housing patterns.

Thus the Court refused to follow the clear, controlling law as laid

down by the United States Circuit Court for the Sixth Circuit in

Deal v Cincinnati Board cf Education (Deal I), 369 F2d 55 (CA 6,

1966), cert den 389 US 847 (1967), and restated in Deal v Cincinnati

Board of Education (Deal II), 419 F2d 1387, at 1392 (CA 6, 1969),

(1971)cert den 402 US 962/ Defendants Milliken, Kelley, State Board of

Education and Porter have no lawful authority over housing.

Moreover this Court has in its findings of fact and con

clusions of law in support of its Ruling and Order of June 14, 1972,

conceded that it has taken no proofs as to the establishment of the

boundaries of the 53 affected school districts nor on the issue

whether such school districts, other than Detroit, have committed

acts of de jure segregation. Yet the Court has imposed racial

balances as to students and faculty in these districts contrary to

Swann, supra, and the recent Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals

decision in Bradley v School District of the City of Richmond,

Virginia, supra.

Based upon such analysis, it can only be concluded that

there is, indeed, strong probability that this Court will be reversed

upon appeal.

The Order of this Court of June 14, 1972 imposes a duty

upon Defendants Milliken, Kelley, State Board of Education, and

Porter to finance and pay the costs of the panel and the local

school districts in cooperating with the panel. Further they must

provide in-service training for teachers and staff and hire black

counsellors. The order sets a fine, closely meshed schedule that

will vitally effect 160,000 children and thousands of teachers by

fall of 1972. Your defendants have no power of the purse. The

12

legislature has made appropriations for their support in discharge

of powers and duties conferred by Michigan law. Payment of expenses

and programs contemplates the expenditure of large sums of public

money that will be irretrievably lost if the decision of the Court

is reversed.

This Court has ordered minimum K-6 integration for

September, 1972 and has imposed a heavy burden upon anyone that

would delay the same. However, the Court has not made the same

requirement for high school pupils, imposing a September, 1973 date.

Under these rulings, it is respectfully submitted that the plain

tiffs will not suffer loss if the Stay is granted.

The public interest demands that the ruling of this Court

be finally reviewed before 160,000 children (K-6) of 800,000 affected

and thousands of teachers, staff and administrators are vitally

affected by change of school assignment in September of 1972. If

this Court is reversed, the trauma of changing schools for the second

time for children will be irreparable. Clearly a Stay is in the

best public interest of all the people of the State of Michigan

until a speedy, final review is secured.

RELIEF

Defendants Milliken, Kelley, State Board of Education

and Porter respectfully request this Court to grant a stay or sus

pension of its Order of June 14, 1972 pending action upon their

petition for certiorari entitled Milliken, et al v Bradley, et al,

October 1971 Term, No 71-1463 by the United States Supreme Court,

or alternatively, pending their appeal to the United States Court

13

of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit from this Court's order of

June 14, 1972.

Respectfully submitted,

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

Assistant Attorney General

Gerald F. Young

Assistant Attorney General

George L. McCargar

Assistant Attorney General

Attorneys for Defendants

Business Address:

720 Law Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

(517) 373-1162

Dated: June 19, 1972