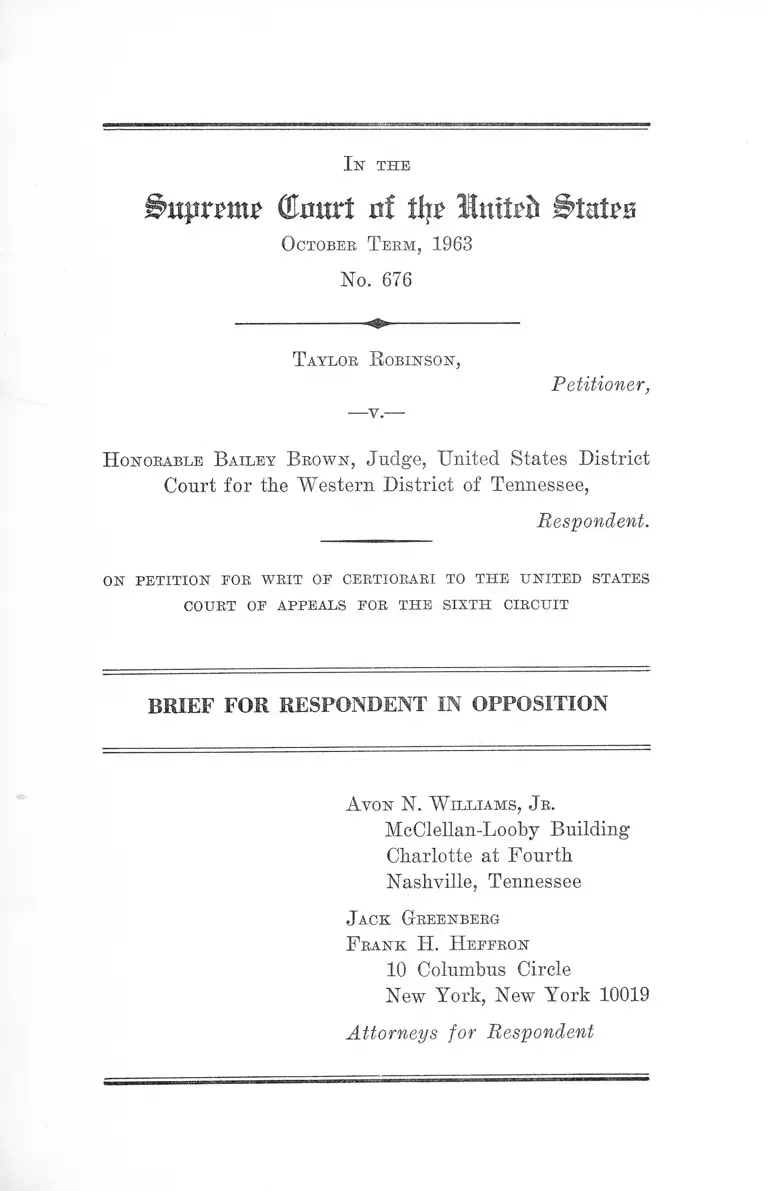

Robinson v Brown Brief for Respondent in Opposition

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1963

14 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Robinson v Brown Brief for Respondent in Opposition, 1963. bb8b54b7-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/06d0d791-566b-459c-bccf-19d469af3765/robinson-v-brown-brief-for-respondent-in-opposition. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Bupxmx Glmirt o f % Mnxttb States

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1963

No. 676

I n th e

T a y l o r R o b i n s o n ,

-v -

Petitioner,

H o n o r a b l e B a i l e y B r o w n , Judge, United States District

Court for the Western District of Tennessee,

Respondent.

ON P E T IT IO N FOR W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E U N IT E D STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR T H E S IX T H CIRCU IT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT IN OPPOSITION

A v o n N. W i l l i a m s , Jr,

McCIellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

F r a n k H . H e f f r o n

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondent

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion B elow ...................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 1

Question Presented.............................................. ------ ------ 1

Statutes Involved....... ........... -............................................ 2

Statement ....................................-...... -................................. 2

A rgum ent ................................................................. -................... 4

The Petition Should Be Denied Because The De

cision Below—Holding That Petitioner Has No

Constitutional Right To A Trial By Jury In A

Purely Equitable Suit—Presents No Conflict With

The Decisions Of This Court And Is Clearly Cor

rect .................................................................................. 4

Conclusion..............................................-.................................... 10

A uthorities Cited

Cases:

Baltimore & C. Line v. Redman, 295 U. S. 654 ....... ....... 4

Beacon Theatres v. Westover, 359 U. S. 500 ....... .—5, 6, 7, 8

Beaunit Mills, Inc, v. Eday Fabric Sales Corp., 124 F.

2d 563 (2d Cir. 1942) ...................................................... 8-9

Brenda K. Monroe, et al. v. Board of Commissioners of

the City of Jackson, Tennessee, et al., Civil Action

No. 1327.................................................. -........................3, 5, 7

Dairy Queen v. Wood, 369 U. S. 469 ....-......................... 5, 6

Dimick v. Schiedt, 293 U. S. 474........................................ 4

11

PAGE

Inland Steel Products Co. v. MPH Manufacturing

Corp., 25 F. R. D. 238 (N. D. 111. 1959) ....................... 9

Shubin v. United States District Court, 313 F. 2d

250 (9th Cir. 1963), cert, denied 373 U. S. 936 ........... 8

Simler v. Conner, 372 U. S. 221 .............................. 5, 6, 7, 8

State Farm Mutual Automobile Ins. Co. v. Mossey, 195

F. 2d 56 (7th Cir. 1952), cert, denied 344 U. S. 869 .... 9

Thermo-Stitch, Inc. v. Chemi-Cord Processing Corp.,

294 F. 2d 486 (5th Cir. 1961) ........................................... 5,7

United States v. Louisiana, 339 U. S. 669 ....................... 5

Statute:

42 United States Code §1983 ............................................ 1, 9

Other Authorities:

Borchard, Declaratory Judgments (2d ed. 1941) ....... 8

5 Moore, Federal Practice, §38.11(7) (2d ed. 1951) .... 4

5 Moore, Federal Practice, §38.16 (2d ed. 1951) ........... 5

5 Moore, Federal Practice, §38.29 (2d ed. 1951)............. 8

I n th e

Olmtrt nf % linxith f l a i r s

October Teem, 1963

No. 676

Taylor E obinson,

Petitioner,

H onorable Bailey Brown, Judge, United States District

Court for the Western District of Tennessee,

Respondent.

ON P E T IT IO N FOR W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E U N IT E D STATES

COURT OF A PPEALS FOR T H E S IX T H C IR C U IT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT IN OPPOSITION

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is reported at 320

F. 2d 503.

Jurisdiction

The jurisdictional requisites are adequately set forth

in the Petition.

Question Presented

In a suit brought under 42 U. S. C. §1983 to desegregate

a public school system, in which an injunction and a declara

tion of rights is sought, is a defendant-school board mem

ber constitutionally guaranteed a trial by jury?

2

Statutes Involved

The pertinent statutes are set forth in the Petition.

Statement

This cause stems from a class action instituted in the

United States District Court for the Western District of

Tennessee, Eastern Division, on January 8, 1963, to de

segregate the public schools of the City of Jackson and

Madison County, Tennessee. The complaint named as de

fendants the Board of Commissioners of the City of Jack-

son and its individual members and the County Board of

Education of Madison County and its individual members,

one of whom is petitioner.

The complaint prayed for injunctive relief against the

racially segregated system of public schools.

The prayer for relief also included the following two

paragraphs:

The Court adjudge, decree and declare the rights and

legal relations of the parties to the subject matter here

in controversy in order that such declaration shall have

the force and effect of a final judgment or decree.

The Court enter a judgment or decree declaring

that the custom, policy, practice or usage of defendants

in maintaining and/or operating compulsory racially

segregated public school systems in and for the City

of Jackson and the County of Madison, State of Ten

nessee, and in excluding plaintiffs and other persons

similarly situated, from the Jackson Senior High

School and Alexander Elementary School, or any other

public schools, institutions or facilities maintained and/

or operated by defendants, City Board of Education

and County Board of Education, solely because of race

3

or color, pursuant to the above quoted portions of

Article 11, Section 12 of the Constitution of Tennessee,

Sections 49-3701, 49-3702 and 49-3703 of the Tennessee

Code Annotated, 1955, and any other law, custom,

policy, practice and usage, violates the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States,

and is therefore unconstitutional and void.

Petitioner answered, demanding, inter alia, trial by jury

(see Petition 41a-42a). On June 1, 1963, the District Judge,

respondent herein, entered an order striking petitioner’s de

mand for jury trial because “ all issues in the case are

equitable” (Petition, p. 5a). Thereupon petitioner, on June

10, 1963, petitioned the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit for a writ of mandamus requiring

respondent to vacate and expunge from the record its order

of June 1,1963.

On June 19, 1963, respondent granted plaintiffs’ motion

for summary judgment in the case, styled Brenda K. Mon

roe, et al. v. Board of Commissioners of the City of Jack-

son, Tennessee, et al., Civil Action No. 1327. The two

Boards of Education were required to file complete plans

for desegregation of the public school system.

On July 31, 1963, the Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit dismissed petitioner’s petition, agreeing with re

spondent that the case involved only equitable issues (see

Petition, p. 8a).

On September 19, 1963, the Court of Appeals denied

petitioner’s application for a stay.

4

A R G U M E N T

The Petition Should Be Denied Because the Decision

Below— Holding That Petitioner Has No Constitutional

Right to a Trial by Jury in a Purely Equitable Suit—

Presents No Conflict With the Decisions of This Court

and Is Clearly Correct.

The Seventh Amendment to the United States Consti

tution directs that

In suits at common law, where the value in controversy

shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury

shall be preserved . . .

The common law referred to is the common law of England

of 1791.1 Thus, the Seventh Amendment, preserving the

right to trial by jury in actions at law, planted deep in

American law the distinction between legal and equitable

causes of action. As new rights of action developed, courts

characterized them as legal or equitable by analogy to their

historical counterparts to decide whether they created

rights to a jury trial.2 The distinction survived the merger

of the federal courts of law and equity in 1938; the common

law forms of action have continued to serve as guideposts

in determining what issues in a civil action are historically

legal and therefore triable to a jury, and what issues are

historically equitable and triable by the court.

Thus, today the conventional test for determining

whether a party has a constitutional right to trial by jury

1 Dimick v. Schiedt, 293 U. S. 474, 476; Baltimore & C. Line v.

Redman, 295 U. S. 654, 657.

2 5 Moore, Federal Practice, §38.11(7).

5

continues to be whether he was entitled to have the issue

tried by a jury at common law.3

So much is recognized by petitioner.4 Petitioner falls

into error, however, in suggesting that legal issues were

presented by the case of Brenda K. Monroe, et al. v. Board

of Commissioners of the City of Jackson, Tennessee, et al.

That case presented no legal— as distinct from equitable—

issues. It was a typical school desegregation case. The

prayer of the complaint was only for equitable relief, i.e.,

an injunction.5 No money damages were prayed for. The

defendants’ answers made no legal issues.

Plainly stated, petitioner was not constitutionally guar

anteed a jury trial in the Monroe case, because Monroe was

strictly a suit for an injunction and presented no legal

issues.

Therefore, the cases relied upon by petitioner are com

pletely inapposite.6 Those cases involved legal issues (e.g.,

breach of contract, damages for infringement of trademark,

treble damages under the anti-trust laws) with claims for

money damages, issues traditionally triable to a jury and

therefore constitutionally guaranteed a jury trial. The

teaching of those cases is simply that a court may not, in a

3 See e.g., United States v. Louisiana, 339 U. S. 699. 5 Moore,

Federal Practice, §38.16 (2d ed. 1951).

4 Petition for Writ of Certiorari, p. 15: “ [I] f there were no

legal issues involved, then there was no basis for issuance of

mandamus.”

5 The complaint sought a temporary restraining order, pre

liminary injunction and permanent injunction enjoining the de

fendants from refusing to admit the Negro plaintiffs to public

schools on the basis of race and directing the defendants to re

organize the school system on a nonraeial basis. See Petition, p. 33a.

6 Beacon Theatres v. Westover, 359 U. S. 500; Dairy Queen y.

Wood, 369 U. S. 469; Simler v. Conner, 372 U. S. 221; Thermo-

Stitch, Inc. v. Chemi-Cord Processing Corp., 294 F. 2d 486 (5th

Cir. 1961).

6

case where both legal and equitable issues are involved, dis

pose of the equitable issues in such a manner as to deprive

the parties of their right to a trial by jury on the legal is

sues.

What distinguishes Beacon Theatres from the instant

case is that there legal issues were blended into the case

by the counterclaim.7 As Dairy Queen v. Wood, 369 U. S.

469, 472 recognized, the holding in Beacon Theatres was

applicable only to a case “where both legal and equitable

issues are presented in a single case.”

Dairy Queen v. Wood, 369 U. S. 469, is similarly distin

guishable. The Court said: “ [T]he sole question which we

must decide is whether the action now pending before the

District Court contains legal issues” (369 U. S. at 473). The

Court answered that question in the affirmative. “ [W ]e

think it plain that [the] claim for a money judgment is a

claim wholly legal in its nature” (369 U. S. at 477).

Likewise, in Simler v. Conner, 372 U. S. 221, the Court

said, “ On the question whether, as a matter of federal law,

the instant action is legal or equitable, we conclude that it

is ‘legal’ in character. . . . The case was in its basic

character a suit to determine and adjudicate the amount

of fees owing to a lawyer by a client under a contingent

7 In Beacon Theatres v. Westover, 359 U. S. 500, Beacon, a mo

tion picture exhibitor, notified Pox, the plaintiff, that certain Pox

exclusive “first run” contracts with movie distributors violated the

Sherman Act and threatened to sue for treble damages. Pox sought

a declaratory judgment that its contracts were lawful and prayed

for an injunction pending final resolution of the litigation to

prevent Beacon from bringing an antitrust suit against Pox or its

distributors. Beacon answered with a counterclaim for treble dam

ages, demanding a jury trial on the factual issues. The district

court viewed the issues raised by the complaint as essentially equi

table and ordered a separate trial of these issues before the court

without a jury. The Supreme Court held that the district judge

abused his discretion in ordering trial of the equitable claim first,

and ordered that the case be submitted to the jury.

7

fee contract, a traditionally ‘legal’ action . . . ” (372 U. 8.

at 223).

Thermo-Stitch, Inc. v. Chemi-Cord Processing Corp., 294

F. 2d 486 (5th Cir. 1961) also involved an action with mixed

legal and equitable issues. The Court said:

The mere presence of an equitable cause furnishes no

justification for depriving a party to a legal action of

his right to jury trial (294 F. 2d at 490-91) (emphasis

supplied).

Petitioner does not deny that all the cases relied upon

involve legal issues. Bather, petitioner seeks to fabricate

a legal issue out of plaintiffs’ prayer for a declaration of

rights with respect to the equitable issues.8 But the inclu

sion of a claim for declaration of rights as to equitable

issues does not, by some mysterious process of judicial

alchemy, transmute those issues into legal issues.

The very cases relied upon by petitioner make that clear.

Beacon Theatres teaches that a declaratory judgment ac

tion is a neuter remedy, neither legal or equitable, and that

a prospective defendant, in an effort to anticipate an action

for which a jury would have been proper, may not employ

the device of a declaratory judgment action to destroy the

other party’s right to jury trial. There Mr. Justice Black

said:

8 The pleadings in the Monroe case (see Petition, p. 33a) make

clear that the declaratory relief sought was merely an adjunct to

the equitable relief of injunction. The principal remedy, and the

only real remedy in the case, was an injunction prohibiting the

exclusion of qualified Negro children from public schools and re

quiring the reorganization of the school systems on a nonracial

basis.

8

[The Declaratory Judgment Act], while allowing pro

spective defendants to sue to establish their nonlia

bility, specifically preserves the right to jury trial for

both parties. It follows that if Beacon would have been

entitled to a jury trial in a treble damage suit against

Fox, it cannot be deprived of that right merely because

Fox took advantage of the availability of declaratory

relief to sue Beacon first. 359 U. S. at 504.

Mr. Justice Stewart emphasized the corollary of the

above proposition, viz., that if the basic issues in an action

for declaratory relief are of a kind traditionally cognizable

in equity, then the issues are properly triable by the court.9

That the basic nature of the issues presented—whether

legal or equitable—controls the question of the right to

jury trial, and not the fact that the action is cast in the form

of a declaratory judgment action, was reemphasized by the

per curiam opinion in Simler v. Conner, 372 U. S. 221.

There the Court said:

The fact that the action is in form a declaratory judg

ment case should not obscure the essentially legal

nature of the action. The questions involved are tradi

tional common law issues (372 U. S. at 223) (emphasis

supplied).

In short, in this suit for an injunction the issues are

purely equitable. These issues become no less equitable by

being cast also in the mold of a declaration of rights.10

To hold otherwise would be to exalt form over substance.

9 359 U. S. at 515.

10 See Shubin v. United States District Court, 313 F. 2d 250

(9th Cir. 1963), cert, denied 373 U. S. 936; 5 Moore, Federal

Practice, §38.29 (2d ed. 1951); Borchard, Declaratory Judg

ments, pp. 238-239, 399-404 (2d ed. 1941) ; Beaunit Mills, Inc. v.

9

Since petitioner is unable to identify any legal issues in

the present suit, he points to legal issues which could arise

if plaintiffs sought damages in this or a later suit. Such

a claim here is at best premature.11 To grant it would be

to destroy the constitutional principle that there is no right

to jury trial in a purely equitable action, since a hypo

thetical legal issue arising in the future can always be

postulated.

Therefore, petitioner’s claim that he has a present right

to a jury trial because hypothetical issues may arise in

the future must fail.

Edwy Fabric Sales Corp., 124 F. 2d 563 (2d Cir. 1942) ; Inland

Steel Products Co. v. MPH Manufacturing Corp., 25 F. R. D. 238

(N. D. 111. 1959) ; State Farm. Mutual Automobile Ins. Co. v. Mos-

sey, 195 F. 2d 56 (7th Cir. 1952), cert, denied 344 U. S. 869.

11 More probably, the claim is totally unfounded. If the Dis

trict Court granted precisely the declaration requested in the

complaint, namely the declaration that the maintenance of school

segregation is unconstitutional, it would afford no basis for a later

finding that petitioner, as an individual, had subjected the plain

tiffs to the deprivation of their constitutional rights in violation

of 42 U. S. C. §1983.

Petitioner seems to agree (Petition, p. 15) :

As was pointed out to the Court of Appeals, it might well be

that the two Boards, as legal entities, had violated plaintiffs’

civil rights. However, this would not mean that each indi

vidual member of each Board had done so. Certainly, any

member less than a majority might be completely innocent of

a Board action taken by the majority. As was pointed out

in the District Court, there is not one shred of evidence, not

one admission, not one witness’ testimony, which would estab

lish that applicant, Taylor Robinson, has been guilty of any

of the acts complained of.

10

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the petition for writ of

certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

A von N. W illiams, Je.

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Jack Greenberg

F rank H. H eeeron

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondent

■

38