Defendants' Trial Memorandum

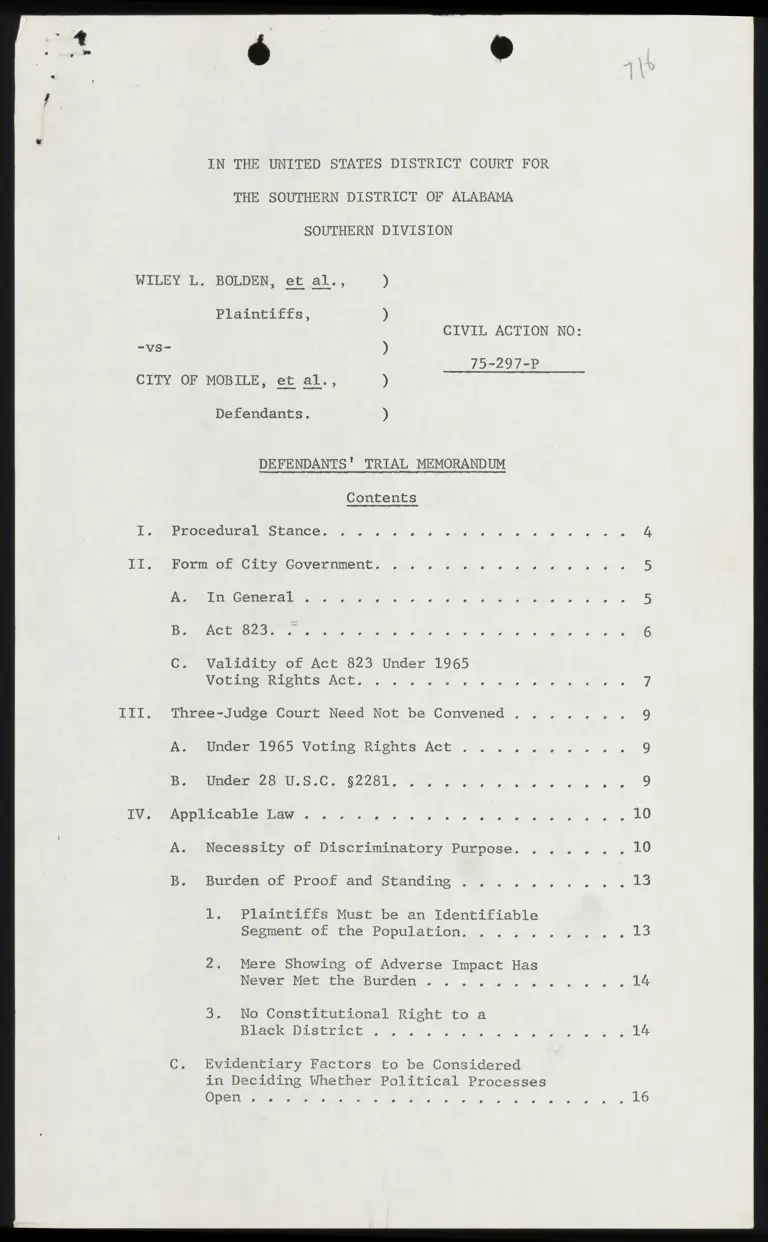

Public Court Documents

July 6, 1976

70 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Defendants' Trial Memorandum, 1976. beb86f54-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/06f6cd21-c0d9-4715-9391-34ee2d7fe9f6/defendants-trial-memorandum. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

WILE

CITY OF MOBILE, et al.,

IY.

11.

IV.

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

Y L. BOLDEWN, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

75-297-~P

CIVIL ACTION NO:

“

N

N

N

N

Defendants.

DEFENDANTS' TRIAL MEMORANDUM

Contents

Procedural Stance, . . . 0 0 Ji

Form of City Government.

A. In General «, 0. . iin se a,

B, Act 823.7%. ov Lo

C. Validity of Act 823 Under 1965

Voring RIshis ACL. . vv vie vie vss

Three-Judge Court Need Not be Convened .

A. Under 1965 Voting Rishts ACL . . vv iv

B. Under 28 U.S.C. §2281.

Applicable Law .

A. Necessity of Discriminatory Purpose. . .

B. Burden of Proof and Standing .

1. Plaintiffs Must be an Identifiable

Segment of the Population.

2. Mere Showing of Adverse Impact Has

Never Met the Burden . ... . .

3. No Constitutional Right to a

Black District

C. Evidentiary Factors to be Considered

in Deciding Whether Political Processes

Open > LJ Ed Ld Ld LJ - LJ LJ * LJ Ld Ld * * Ld Ld *

. 14

16

a

;

. I. VPrimary PactorS. . . J va vine : . 16

2. "Enhancing Pactors. . . hi. sii, eid in 7

V. Defendants! Contentions of Fact . . , vii isis" 18

A. Tdentifiasble Segment. i. '« . ivi ie vie 18

B. Discriminatory Purpose. . . . iv 4 0 a wie 19

C. Effect: The Zimmer Criteria. ., . ... . .-. 5.2%

1, Npeimaey Paeckors » . i. ov vind een

(a) No "lack of access to the process

of slating candidates’, , . , .. . Vo... 21

(b) No "unresponsiveness of legislators

to [blacks'] particularized interests'. 23

(1) Clty Services . . i. tv vie 2 una 23

(il) Boards & Commissions. . . . . . . . 26

(iii) Disparity in Employment

SEACISELCS, vw vue 0 iia ara 26

(c) No "tenuous state policy underlying

the preference for multi-member or

gtelaree districting LiL. Lu. 27

(d) No "existence of past discrimination

in general preclud[ing] the effective

participation in the electoral system'. 28

(e) Summary of "Primary" Factors. . . . . . 30

2. Enhancing” Factors « '. u,v a. 0530

(a) Large Districts. . .. ih Jd, 0.52, 30

(b) Majority Vote Requirement . . . . . . . 30

(¢) Anti-Singleshot Voting Provision. . . . 30

(d) Lack of Residence Requirement . . . . . 31

(e) Summary of "Enhancing' Factors and

VAgoregate' of ‘All Factors. . ... J. .,.32

VI. Defenses and Other Pertinent Considerations . . . 33

A. Traditional Tolerance of Various Forms

Of Local.Bovernmentk. . , i, ou Ja, Jit ipnionas 33

B. Necessity for Change in Form of City

Government if Single-~Member Districts

OrQeradi, oir hy Fie ie i i pa Bh

Cel Swing Vote. vv so ov ons set Sly, LR [BS

D. Banzhaf theory. RR TTR RB SR |

FE." Ciry~wide Perspective . . .. v.ofe 4 v4 vi vv's 36

F. Increased Polarization and Possible

"Minority Freeze-out' Under Single-

Member Plan. or. ve ere ay 0B

G. Single~Member Districting and New

Constitutional Proplems . . i. . oo + iv vin uw 38

1. Reapportionment... . . . ... . 5 uiis Joe . 38

2. CorrymanderIng., . + 4 se ois ive a. v0 wrria 39

H. Flexibility of Federal Equitable Relief . . . . 40

VII, Available Political Remedy . . , ic. "ue vivian hl

A. Legislative RemeBy. i. oi vst oie sv iniviviehy

Be AD ONAONNBII i, i ie ee aT ee aT NE AD

Appendix: City of Mobile Governance (18l4-present)

ear A RE RR ST nt 0 SE BN A BS SB 3 Ty Re RE i A i i A a eli”

I. PROCEDURAL STANCE

Plaintiffs,! as named representatives of a class com-

posed of black citizens of the City of Mobile,” brought

suit in this Court? claiming that the system of at-large

election of the three Commissioners of the City of Mobile

abridges the rights of plaintiffs and the class they rep-

resent, guaranteed to them under the First, Thirteenth,

Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution

of the United States. The plaintiffs' claims are asserted

under 42 U.S.C. §§1973 and 1983.4

> and each of the Defendants are the City of Mobile,

: 6

Commissioners of the City of Mobile, Gary A. Greenough,

Robert B. Doyle, Jr., and Lambert Mims.

Lhe remaining named plaintiffs are Wiley L. Bolden,

R. L. Hope, Janet O. LeFlore, John L. LeFlore, Charles

Maxwell, O. B. Purifoy, Raymond Scott, Sherman Smith, Ollie

Lee Taylor, Ed Williams, Sylvester Williams, and Mrs. F. C.

Wilson. Plaintiffs Johnson and Turner voluntarily dismissed

their claims, and Scott and Williams have moved to do so.

Plaintiff John LeFlore died during the pendency of this

cause, but his death was not suggested upon the record.

2 he complaint alleged a class claim under Rule 23(b) (2)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The action was cer-

tified as a class action by order dated January 19, 1976.

3The jurisdiction of this Court was invoked under 28

U.S.C. §§1331-1343,

ba claim originally asserted under 42 U.S.C. §1985(3)

was dismissed for failure to state a claim upon which relief

can be granted.

5

The City of Mobile is sued only under 42 U.S.C. §1973.

Claims against it based upon 42 U.S.C. §1983 and 1985(3)

were dismissed by order of the Court on November 18, 1975.

6

The three Commissioners are each sued in their indi-

vidual and official capacities. C. WRIGHT, LAW OF FEDERAL

COURTS §48 (1970).

Plaintiffs seek a declaratory judgment that the at-

large election of City Commissioners violates the Consti-

tution of the United States, and seek also an injunction

against any city election under the present plan. Plain-

tiffs also seek to have defendants enjoined "from failing

to adopt" a single-member city government plan.’

IT, FORM OF CITY GOVERNMENT

A. In General. The City of Mobile, over its history

(at least since prior to the statehood of Alabama) has had,

in its city government, at least some feature or form of

at-large election. A chart tracing in brief the governance

of the City since 1814 is attached hereto as "Appendix A"

for the convenience of the Court.

Since 1911, the City has been governed by a com-

mission form of government established by the Legislature

of the State of Alabama. Ala. Acts No. 281 (1911) (pre-

sently codified principally as ALA.CODE tit. 37, §89, et.seq.)

Under the commission form of government as it obtains in

Mobile, three commissioners are elected to numbered posi-

tions. Each come dionas engages in specific administrative

tasks involving certain city departments under his control.

One commissioner also serves as the Mayor, a largely cere-

monial post. All commissioners are elected at-large by the

entire City; that is mandated by the provisions of ALA.CODE

tit. 37, §89. While the at-large requirement is part of a

Defendants moved to strike this claim for relief upon

the ground that they had no power to adopt a single-member

plan, since only the state legislature has that power. The

motion was denied at that stage of this case.

. statute general in nature and not by its terms limited to

Mobile, this is not, as will be discussed infra, a Three-

Judge Court case.

B. Act 823. In the course of the trial, referecice

may be made to Act 823 of the 1965 Alabama Legislature, a

general act of local application® enacted solely for the

benefit of Mobile. As will be discussed infra, a question

has been raised outside this Eom; respecting the validity

of this statute under the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which

need not be decided in this case.

If Act 823 is valid, each commissioner is elected

to a post which has assigned to it by that statute certain

specific administrative duties. The mayoralty is rotated

among the three commissioners in a statutorily~-ordained

fashion. The City of Mobile has been operating under Act

823 since 1965,% and remains of the view that it is valid

8 he meaning of this term is explained in Adams,

Legislation by Census: The Alabama Experience, 21 ALA. 1.

REV. 401(1969). The Three-Judge Court implications of that

practice are discussed, infra.

The administrative and mayoral-rotation features of

Act 823 were by no means new to the Mobile Commission gov-~

ernment in 1965, but had come and gone from time to time in

; earlier decades of the twentieth century. In 1939, Act 289

was introduced by Mr. Langan and passed, providing for elec-

tion of the Mayor for that specific office, and also provid-

ing a specific apportionment of the tasks of administration

among the two associate commissioners. It was declared un-

constitutional the next year for repugnancy to legislative

requirements (procedural in nature) under the Alabama Consti-~

tution. State v. Baumhauer, 239 Ala. 476, 195 So. 869(1940).

Almost immediately thereafter the same basic provision was

re-enacted in the general codification of 1940. ALA. CODE

tit. 37, §95(1940). One associate commissioner was assigned

the fire, police, health, and sewer departments, while the

other was assigned parks, docks, streets, public buildings,

and the city airport. The majority of the Board of Commissioners

assigned to each associate commissioner one set of tasks. In

1945, this procedure was abandoned. Ala. Acts No. 295(1945).

. without the approval of the Justice Department under the

Voting Rights Act of 1965.

If Act 823 is covered by the Voting Rights Act

and is therefore invalid until made the subject of a declara-

tory judgment action in the District of Columbia, then the

same commissioners are still elected to the same numbered

posts under Act 281 as amended, and one of their number still

serves as Mayor. ALA.CODE tit. 37, §§94-95. The difference

would be that the majority of the commissioners would se-

lect the largely ceremonial mayor (rather than by a set

rotation), and the majority of the commissioners would appor-

tion among themselves the various administrative tasks

(rather than under a SEatutony apportionment of tasks).

The commissioners would still be elected to numbered posts.

Id. at §94.

Whether or not Act 823 is valid, the commissioners

are elected at-large. ALA.CODE tit. 37, §96. 1It is of course

the at-large feature of the plan which is under constitu-

tional attack in this case; not the method of apportioning

the administrative tasks or the method of rotating the

largely ceremonial mayoralty among the commissioners.

C. Validity of Act 823 Under 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Act 823 presents a problem of the coverage of §5 of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, but that is a problem which need

not be decided in this case. The validity of that statute

has not been called into question in this case by plain-

tiffs, either under the pleadings or pretrial order, despite

the specific invitation of defendants in the course of

proceedings in the Justice Pepavtment. 1° If the validity of

Act 823 is called into question in this case, and if it is

also necessary to decide that issue, it will of course be

necessary to convene the special statutorily-mandated Three-

Judge District Court to decide that issue. _Allen v. Bd. of

Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 563(1969).

Even if the validity of Act 823 should be called

into question in this case, though, it will not be necessary

to decide the issue. Since plaintiffs cannot successfully

prove a discriminatory purpose in the enactment of the 1911

statute, as required under a very recent Supreme Court case

~ (discussed infra), and since plaintiffs cannot even prove

a discriminatory effect under the Fifth Circuit Standards

100k 823 was enacted shortly after passage of the 1965

Voting Rights Act, and was not at the time submitted to the

Department of Justice. On May 14, 1975, the City of Mobile

submitted to the Justice Department five statutes of the 1971

Regular Session of the Alabama Legislature for approval under

§5 of the Voting Rights Act. On July 14, 1975, the Justice

Department wrote the City to ask that Act 823, which had been

minimally amended by one of the 1971 enactments, be submitted

for approval under §5. On December 30, 1975, the City sub-

mitted Act 823 "without prejudice to the right of the City

to continue to insist upon its position that Act 823 is not

within the scope of the Civil Rights Act of 1965". On March

2, 1976, the Department of Justice interposed objection to

portions of Act 823, upon the rationale that since the City

was contending in this litigation that Act 823 made the impo-

sition by this Court of single-member districting inappro-

priate, Act 823 was invalid since it ''rigidifies use of the

at-large system''. On March 5, 1976, counsel for the City

wrote the Department of Justice reiterating the City's

position that Act 823 was without the coverage of §5, and

specifically by copy inviting plaintiffs in this action "to

bring an appropriate legal action to determine the matter,

if they are disposed to contend that it is unenforceable'.

Neither plaintiffs herein nor the Department of Justice have

done so; nor has the City instituted a declaratory judgment

action under §5 in the United States District Court for the

District of Columbia. There is, of course, a serious ques-

tion as to whether or not Act 823 is covered by §5 of the

1965 Voting Rights Act. See generally Beer v. United States,

U.S, +47 L.24.2d 629(1976).

prevailing prior to the new Supreme Court 'purpose' test,

plaintiffs cannot prove their case. Since the issues raised

by the pleadings and pretrial order are all single-judge

issues upon which the case can be decided without reference

to any three-judge issue (validity vel non of Act 823), the

Court can proceed to a decision on the merits of this case

without a Three-Judge Court's decision on the validity of

Act 823. MTM v. Baxley, 420 U.S. 799, 806-07(1975) (concur~-

ring opinion); Hagans v. LaVine, 415 U.S. 528(1974).

III. THREE~JUDGE COURT NEED NOT BE CONVENED

No party in this case has suggested that a Three-Judge

Cours be convened, nor has the Court raised the issue sua

sponte. However, because of the complexity of the issue,

a paragraph on that problem may be appropriate.

A. Under 1965 Voting Rights Act. As has been pre-

viously discussed, it is not necessary to convene a Three-

Judge Court under the special provisions of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965, since this case can be decided upon the

basis of single-judge issues.

B. Under 28 U.S.C. §2281. A Three-~Judge Court need

not be convened in this case under the provisions of 28

U.S.C. §2281, the general Three-Judge Court statute.

Plaintiffs seek, in effect, an injunction against

the enforcement of parts of ALA.CODE tit. 37, §89, et.seq.,

the present codification of Act 281 of the 1911 Alabama

Legislature, as amended. Specifically, the at-large feature

is contained in ALA.CODE tit. 37, §96. Mobile has been gov-

erned by the provisions of Act 281 (as amended) since 1911.

“10

Hartwell v. Pillans, 225 Ala. 685, 686, 145 So. 148(1949).

While Act 281 purports to be a general act, Baumhauer v.

State, 240 Ala. 10, 12, 198 So. 272(1940), it is impossible

to tell what cities other than Mobile, if any, have elected

to be governed by the statute. There are indications that

Act 281 (or at least parts of it) constitute a general law

of local application. Cf. State v. Baumhauer, 239 Ala. 476,

196 So. 869(1940). While the statute purports to be general

in nature, no Three-Judge Court need be convened because

(1) an injunction is sought only against local officials, and

(2) the statute is of local impact, solely (or at least prin-

cipally) in Mobile. Bd. of Regents v. New Left Education

Project, 404 U.S. 541, 544(1972); Moody v. Flowers, 387 U.S.

97(1967). This case is much more fundamentally "local" than

Holt Civic Club v, City of Tuscaloosa, 525 F.2d4.:653 (5th Cir.

1975), where plaintiffs were a class of all "Alabama resi-

dents" who lived in police jurisdictions surrounding cities,

where the statute was genuinely state-wide in application,

and where local officials were sued only because they were

the only officials who could enforce the statute in the

various Alabama cities.

IV. APPLICABLE LAW

A. Necessity of Discriminatory Purpose. The United

States Supreme Court quite recently decided Washington wv.

Davis, U.S. s 04 U.8.L..W., 4789 {U.8S. June 7, 1976),

making clear that before a court can declare a statute un-

constitutional by reason of its being ''racially discrimina-

tory', the statute must first be proved to have a ''racially

discriminatory purpose'l, U.S. aL , 44 U.8.L.W, at

5

4792 (emphasis added). Washington v. Davis thus clarified

an issue which a number of cases--including multi-member dis-

tricting cases--had left as ''somewhat less than a seamless

web". Beer v. United States, U.S. s 47 L.Ed.24

269, 643 n.4(1976) (dissent) . Lt While Washington technically

involved equal protection analysis only, 12 the Court made

quite clear that it was announcing a broad principle of

constitutional law, including the Fifteenth Amendment as

well. Writing that "[tlhe rule is the same in other con-

texts", Washington specifically reaffirmed Wright v. Rocke-

feller, 376 U.S. 52(1964), a case requiring proof of

discriminatory purpose where voting districts were alleged

to have been racially gerrymandered in contravention of the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendment rights of black plain-

Ci€fa, U.S. at s O4 U.8.L.W. at 4792,

Mine holdings of several courts were unclear on the

necessity of showing of discriminatory purpose. The Supreme

Court in Chavis v. Whitcomb, 403 U.S. 124, 149(1971), seemed

to require proof of discriminatory purpose (''purposeful’,

""designed'"). See Graves v. Barnes, 378 F.Supp. 640, 665

(W.D. Tex.1974) (dissent), opinion on remand of White v.

Regester, 412 U.S. 755(1973). The Fifth Circuit in 1974

wrote that "[i]t is unclear whether dilution of a group's

voting power is unconstitutional only if deliberate..."

Reese v. Dallas County, Ala., 505 F.2d 879, 886(5th Cir.1974),

rev'd other grounds, 421 U.S. 744(1975). But the Fifth Cir-

cuit earlier had seemed to say that effect had greater rele-

vance than did purpose. Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297,

1304 n.16(5th Cir.1973) (en banc), aff'd. sub.nom. East

Carroll Parish School Bd, v. Marshall, Uu.s. , (March

8, 1976) (where the Supreme Court stated that its affirmance

was "without approval of the constitutional views expressed

by the Court of Appeals').

120he case involved the operation of the police department

of the District of Columbia, which is not a ''state' bound by

He strictures of the Fourteenth Amendment. However, as the

ashington Court noted, it was held shortly after Brown v.

5 of Educ. "that the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amend-

ment contains an equal protection component prohibiting the

United States from invidiously discriminating between indi-

viduals or groups. Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497(1954)".

U.S. at , 44 U,8.L.W, at 4792,

rr.

12

That the rule of Washington v. Davis obtains in a multi-

member district voting dilution case has also quite recently

been recognized in the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Alabama, in Rev. Charles H. Nevett v.

Lawrence G. Sides, et al., C.A. 73-P-529-S (Order of June 11,

1976). While that case will be discussed in more detail

infra’? it is informative here that after Judge Pointer made

specific factual findings for the defendant City, he also

added that "It may be noted that there has been no evidence

that the claimed 'dilution' was the result of any invidious

discriminatory purpose. Cf. Washington v. Davis..." Id.

Therefore, the Alabama statute attacked by plaintiffs

in the instant case is not due to be held unconstitutional

unless its enactment was motivated by a racially discrimina-

tory purpose. 1?

Whatever may pave been the dicta, or even the holdings,

of Fifth Circuit and lower court cases that pre-~date

Washington, it is now certain that evidence of discriminatory

13priefly, that case involved a suit quite similar to

this one, involving multi-member districting in the City of

Fairfield. After the District Court found for the plaintiff

in an unreported decision, the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit reversed for more specific factual find-

ings on the factors outlined in Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d

1297(5th Cir.1973). Nevett v. Sides, F.2d (5th Cir.

June 8, 1976). On remand, the District Court found for the

City the day after receipt of the mandate. Nevett v. Sides,

F.Supp. (N.D. Ala. June 11, 1976). Copies of the

decision of the Fifth Circuit and of the District Court on

remand are attached hereto for the convenience of the Court.

Ye fact that the city government statute is said to

violate 42 U.S.C. §1973(c), as well as the Constitution it~

self, does not change the result. That statute tracks the

language of the Fifteenth Amendment and is ''constitutional

in nature". Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d 619, 634 n.17 (5th

Cir.1975), vacated on other grounds, B.S. > 47

L..Ed.2d4 2956(1976).

® 1s »

effect is relevant and admissible only for whatever light,

if any, it may cast upon purpose-~-the decisive issue.

B. Burden of Proof and Standing. The plaintiffs, of

course, have the burden of proof:

The plaintiff's burden is to produce evi-

dence to support findings that the poli-

tical processes leading to nomination and

election were not equally open to parti-

cipation by the group in question--that

its members had less opportunity than did

other residents in the district to parti-

cipate in the political processes and to

elect legislators of their choice.

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 766(1973).

1. Plaintiffs Must be an Identifiable Segment of

the Population. As an initial matter, plaintiffs have the

burden of proving that they constitute under the present

facts an identifiable class for Fourteenth Amendment purposes.

While dilution cases such as this are most commonly brought

by blacks, membership in the Negro race is not talismanic;

nor is the doctrine reserved exclusively for blacks. The

Supreme Court in one recent case held that blacks as such

did not constitute an identifiable class; under the circum-~

stances of that case blacks were held to be not dissimilar

from non-black Bemocrats. for example:

[Tlhe interest of the ghetto residents

in certain issues did not measurably

differ from that of other voters.

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 155(1972) (claim of dilu-

tion '"'seems a mere euphemism for defeat at the polls", Ié.

at 153).

The Supreme Court has long suggested that the dilu-

tion doctrine extends to political as well as racial elements

of the population id and has suggested strongly that blacks

15Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73, 88(1966); Fortson v.

Dorsey, 379 U.8. 733, 739(19653).

a — A AS TIS S ER SU as OF TT ATI EE med Bt eis

1k

need not necessarily fare better in a dilution case under

the Constitution than, for example, "union oriented workers,

the university community, or religious or ethnic groups

occupying identifiable areas of our heterogeneous cities and

urban areas". Whitcomb v, Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 156(1971)..

In order to invoke the benefit of the dilution doctrine,

blacks must prove more similarity than mere blackness. As

one post~-Chavis commentator wrote,

After all, if Republicans could have

elected someone more sympathetic to

their views in the absence of a multi-

member district, are they not suffering

the same harm blacks suffer...? Certain-

ly in the case of de facto racial submer-

gence, where racial intent is not shown,

blacks are not suffering because they

are black.

Carpeneti, Legislative Apportionment: Multi-member Districts

and Fair Representation, 120 U,.PA.L.REV. 666, 698(1972).

2. Mere Showing of Adverse Impact Has Never Met

the Burden. Even prior to the decision of the Supreme Court

in Washington v. Davis, a plaintiff could not meet his bur-

den by showing a mere adverse impact, but had to prove more:

The critical question under Chavis and

Regester is not whether the challenged

political system has a demonstrably

adverse effect on the political fortunes

of a particular group, but whether the

effect is invidiously discriminatory,

that is, fundamentally unfair.

Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d 619, 630 (5th Cir.1975), vacated

& remanded on other grounds, u.8s. , 4721.54.24

296(1976) (per curiam) (emphasis added).

3. No Constitutional Right to a Black District.

Plaintiffs have no constitutional right to a politically

safe black district. The Fifth Circuit has recently reiter-

ated that the Supreme Court's pronouncements reject such a

"ouaranteed district" concept:

-15

Chavis and Regester hold explicitly that

no racial or political group has a con-

stitutional right to be represented in

the legislature in proportion to its num-

bers, so it follows that no such group is

constitutionally entitled to an apportion-

ment structure designed to maximize its

political advantages...Neither does any

voter or group of voters have a constitu-

tional right to be included within an

electoral district that is especially

favorable to the interest of one's own

group, or to be excluded from a district

that is dominated by some other group.

Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d 619, 630 (5th Cir.1975), vacated

& remanded on other grounds, U.8. . 47 1..84.24

296(1976). Accord, Vollin v. Kimbel, 519 F.2d 790, 791

(4th Cir.1975) (''black voters are not constitutionally enti-

tled to insist that their strength as a voting bloc be pre=-

served"), cert.den., U.S. (1976); Cherry v. County

of New Hanover, 489 F.2d 273, 274 (4th Cir.1973) (blacks

"do not have a constitutional right to elect members of their

race to public office'). The Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit in the Fairfield case, in reversing the holding of

the District Court, recently sphineized that blacks are not

to be guaranteed a politically-safe district of their own:

The trial court's findings may be read

as indicating that elections must be

somehow so arranged-~-at any rate where

there is racial bloc voting-~that black

voters elect at least some candidates

of their choice regardless of their

percentage turnout. This is not what

the Constitution requires.

Nevett v. Sides, F.2d FR {Sth Cir, June 8, 1976).

Plaintiffs in order to prevail have always had to

show, as Wallace v. House indicates, that the system is

"fundamentally unfair'. 515 F.2d at 630. Now, after

Washington v. Davis, they must show (1) that the system is

«16«

"fundamentally unfair", and (2) that it was intended to be so.

C. Evidentiary Factors to be Considered in Deciding

Whether Political Process Open. Cases decided prior to

Washington developed a number of evidentiary criteria to be

considered upon the principal issued raised by White--wheth-

er "the political processes leading to nomination and

election" are "equally open'. White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

766. These criteria (being pre-Washington) relate to effect

only, and have been wariously stated from time to time and

from case to case, and even from Court to Court.

As formulated in Zimmer, these indicia of discrim-

inatory effect comprise "a panoply of factors'. Proof of

"an aggregate of these factors' may suffice to prove effect,

485 F.2d at 1305; the factors do not include intent, since

Zimmer preceded Washington. These factors were in Zimmer

divided further into what may be termed 'primary'" and

"enhancing' factors. Id.

1. "Primary'' Factors. The following factors from

Zimmer were held in that case to be indicia of dilution of

the votes of blacks (Id. at 1305):

(a) "Lack of access to the process of slating

candidates;

(b) "Unresponsiveness of legislators to their

16Ccommentators analyzing the Fifth Circuit's en banc de-

cision in Zimmer v. McKeithen have suggested that a civil

rights plaintiff may more easily prevail under the Zimmer

criteria than under the Supreme Court cases which Zimmer pur-

ported to follow. See, e.g., Note, 87 HARV.L.REV. 1851, 1858

(1974) ; Note, 26 ALA.L.REV, 163, 170(1973) . Support is lent

to this by che pointed remark of the Supreme Court in Zimmer

that it was affirmed "without approval of the Constitutional

views expressed by the Court of Appeals'. East Carroll Parish

School Bd. wv. Marshall, U.8. (March 8, 1976), aff’ =.

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) (en banc).

i Tp

[blacks'] particularized interests';

(c) "A tenuous state policy underlying the

preference for multi-member or at-large districting'';

(d) "The existence of past discrimination in

general precludes the effective participation in the election

system'.

2. "Enhancing' Factors. Zimmer also says that

proof of dilution made out by a showing of the above-enumer-

ated factors may be "enhanced by" (Id. at 1305) the following

factors:

(a) "The existence of large districts'';

(b) "Majority vote requirements'';

(¢) "Anti-singleshot voting";

(d) "The lack of provision for at-large can-

didates running from particular geographical subdistricts'.

Because these factors have been explicitly followed

17

in later (but pre-Washington) Fifth Circuit decisions, they

probably ought, out of an abundance of caution, to be the

basis here of factual findings on effect, notwithstanding any

differences between Zimmer and Supreme Court precedent. 8

17Nevett v. Sides, F.24, {5th Cir. June 8, 1976);

Perry v. City of Opelousas, 515 F.2d 639 (5th Cir.1975);

Wallace v, House, 515 F.24 619 (5th Cir.1975); Turner v.

IcKeithen, 490 F.2d 191(5th Cir.1973). Nevett was decided

the day after Washington, but contains no mention of it.

“See note 16 supra. The Three-Judge District Court on

the remand of White v. Regester formulated the factors in-

volved in a different and slightly less Procrustean fashion

than appeared in Zimmer and its progeny. See Graves v. Barnes,

378 F.Supp. 640, 643 (W.D. Tex.1974), on remand of White wv.

Regester, 412 U.S. 755(1973).

<15~

Therefore, the findings of fact we will propose to the Court,

in order to insure a complete record, will address the dic-

tates and factors stated in both Washington v. Davis (intent)

and Zimmer v. McKeithen (indicia of effect), keeping in mind

that "unless [the Zimmer] criteria in the aggregate point to

dilution..., then plaintiffs have not met their burden, and

their cause must fail''. Nevett v. Sides, F.2d

Sera ———

(5th Cir. 1976).

V. DEFENDANTS' CONTENTIONS OF FACT

A. Identifiable Segment. The evidence which will be

adduced in this case will indicate that blacks in Mobile

have interests and needs which, as in the Chavis case, '[do]

not measurably differ from that of other voters". 403 U.S.

19 there would be a factual basis at 155. That being so,

for a finding that blacks do not in fact, except for their

blackness and a common racial history, constitute an "'iden-

tifiable segment'. While defendants do not ask that this

Court make such a finding on the standing issue, it will be

useful in considering the merits of this case to remember

the fact (and it is a fact) that the needs of blacks on most

issues do not appreciably differ from those of whites.

Bror example, the testimony of Dr. James E. Voyles, an

expert for defendants, indicates that black/white political

scisms of the 1960's were an aberrant product of the civil

rights struggle during that period, and that black/white

scismatic voting trends have been significantly (if not yet

entirely) reduced. Similarly, the answers of the named

plaintiffs to interrogatories indicate many examples of

identity of black/white views, thus reducing the number of

issues upon which the blacks have '"particularized needs".

See, e.g2., Answers of Plaintiffs to Defendants' Interroga-

tories 67-114.

“~10~

B. Discriminatory Purpose. Under Washington wv. Davis,

plaintiffs must prove that the statute involved was enacted

or instituted to further a discriminatory purpose. The

statute under attack here was enacted in 1911,

Since blacks in 1911 constituted a political cipher

both in Mobile and state-wide, having been overtly eliminated

from the electorate shortly after the adoption of the Ala-

bama Constitution of 1901,%° any contention that the adop-

tion of Act 281 was racially motivated is unsupportable.

The Fifth Circuit has several times held (apparently

judicially noticing the fact) that many if not most Southern

election statutes of the late nineteenth or early twentieth

century were totally neutral racially, since blacks had been

directly and overtly disfranchised by direct means. For

example, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in

Wallace v. House held that when the at-large election system

was first passed in Louisiana in 1898, 'there could have

been no thought that the device was racially discriminatory,

because very few blacks were allowed to vote in Louisiana

during that period. 515 F.2d at 633. Judge Wisdom made

a similar observation in Taylor v. McKeithen, finding that

prior to the 1965 Voting Rights Act,

blacks could not be elected to [public

office] -~to be blunt--because there

were no black voters. It is as simple

as that. Since adoption of the Louisi-

ana Constitution of 1898 and until re-~

cently, the legislature disfranchised

blacks overtly; it was never necessary

for the legislature to resort to covert

20h [Alabama] Constitution of 1901...eliminated the

Negro voter". M. McMILLAN, CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN

ALABAMA 354 (1955).

«20 ~

disenfranchisement (sic) of blacks by

manipulating [apparently neutral elec-

toral devices].

499 F.2d 893, 896 (5th Cir. 1974) ,quoted in Wallace v. House,

515 F.2d at 633. Additionally, we expect the evidence to

show that the commission form of government was adopted in

Mobile for reasons completely unrelated to race.

This Court should make a finding in this case that

Act 281 was enacted for a non-discriminatory purpose and,

under Washington v. Davis, that finding should end the

inquiry, with judgment for defendants being mandated.

However, defendants recognize the position of this

Court in the present case. Washington v. Davis, clear. though

it is, did not expressly overrule the Zimmer case and its pro-

geny (which grew like Topsy notwithstanding apparent conflict

with White v. Regester and other pre-Washington cases?ly

and no Fifth Circuit case has yet considered to what extent

” : 22

(if at all) the Zimmer case survives Washington.

Because the Zimmer case stands unreversed to date,

‘and also since Washington leaves some room for admissibility

of evidence of effect as it might bear on purpose in an appro-

priate case, defendants recognize that the Court may want to

make factual findings upon the Zimmer criteria of discriminatory

21lgee n.16, supra.

22. : he

The Supreme Court, even before Washington, seems in its

narrowly-grounded affirmance of Zimmer to have suggested the

invalidity of the constitutional holding of Zimmer under prec-

edent prevailing even at that time. East Carroll Parish

School Bd. v. Marshall, U.S.. © (march §, 1976) (aff'd.

"without approval of the constitutional views expressed by

the Court of Appeals').

-21-

effect, for whatever residual value they may have after

Washington.

C. Effect: The Zimmer Criteria,

1. "Primarv' Factors.

(a) No "lack of access to the process of slat-

ing candidates'. Blacks in the City of Mobile have not

been deprived of access to the slating of candidates to the

City Commission; in Mobile there is no such slating. This

fact parallels the finding of Judge Pointer in the Fairfield

2 Ld > Ld Ld »

case. 3 However pernicious the operation of slating organi-

zations might be in other cities,?? they do not exist in

Mobile city elections. In fact, not only are there no non-

partisan slating organizations for the City Commission in

Mobile, the elections are non-partisan and the Democratic

and Republican parties themselves do not serve as slating

organizations fiche City Commission. All that is necessary

is for a potential candidate to qualify and to run.

A few other, more general observations concerning

231 The plaintiffs, blacks residing in the City of Fair-

field, have not demonstrated any lack of access to the process

of slating candidates for city elections; for in Fairfield

there has been no such slating'". ©Nevett v. Sides, F.

Supp. (N.D. Ala. June 11, 1976).

24 In Dallas City Council elections, a slating organiza-

tion styled the "Citizens Charter Association', or C.C.A.,

"enjoyed dominance" in city elections. Lipscomb v. Wise, 399

F.Supp. 782, 786 (N.D. Tex.1975). A similar group, called the

"Dallas Committee for Responsible Government' or DCRG operated

in elections from that county to the state legislature. White

v. Rezester, 412 1.8. 755, 766-67(1973). In other cases,

political parties or party organizations with racial solidar-

ity served the same function. E.g., Turner v. McKeithen, 490

F.2d 191, 195(5th Cir.1973) (one-party parish where black

vote solicited only after nomination). There is no such

monolithic political organization in Mobile City Commission

elections.

wm

Mobile political affairs may be in order in view of the

suggestion of the Supreme Court in White that these cases

call for an "intensely local appraisal...in the light of

past and present reality, political and otherwise. 412

U.S. at 769,

Unlike many southern polities in which nomination

by the Democratic Party is tantamount to election, that is

not necessarily so in Mobile, even in races which (unlike

the City Commission races) are conducted on partisan tickets.

There is no longer any racial impediment of whatever

nature to prohibit or hinder in any way a black (as such)

from registering to vote, voting, qualifying to seek office,

running for office, or paling elected to office. In sum,

Mobile has an intensive, active, vigorous political life,

one which, at the present time, is as open to blacks as to

whites. As the Siprene Court wrote in Chavis:

~~

The mere fact that one interest group or

another concerned with the outcome of...

elections has found itself outvoted and

without legislative seats of its own

provides no basis for invoking constitu-

tional remedies where, as here, there is

no indication that this segment of the

population is being denied access to the

political system.

£03 B.S. 15. 154-55,

To whatever degree (if any) White v. Regester differs

25 ‘ : a

from and therefore controls Zimmer, this finding alone

should compel judgment for defendants. The Supreme Court

in that case wrote, as noted above, that the burden was on

plaintiffs to prove that their segment of the population

255ee n.l6, supra.

~23-

"had less opportunity than did other residents in the

district to participate in the political processes and to

elect legislators of their choice'. 412 U.S. at 766. The

finding of openness under this single Zimmer criterion appar-

ently, under White, answers the entire question: if the

political process is open to blacks, there is no dilution.

(b) No "unresponsiveness of legislators to

[blacks'] particularized interests'. As an initial matter,

it may be noted that the evidence will reflect that on many

issues of importance to citizens in Mobile there are no

"particularized interests' of blacks.

A significant segment of the proof adduced by plain-

tiffs on the responsiveness issue is expected to be in the

form of testimony concerning isolated instances of citizen

complaints about, for example, drainage or paving in a par-

ticular area inhabited largely or entirely by blacks. As

Judge Pointer pointed out in the Fairfield case,

it should be noted that the inquiry is

directed to '"unresponsiveness', referring

to a state, condition or quality of being

unresponsive, and is not established by

isolated acts of being unresponsive.

Nevett v. Sides, F.Supp. (N,D. Ala, June 11, 1975),

Defendants expect the evidence to show that the

City of Mobile has not, in recent years, evidenced unrespon-

siveness to particularized needs of blacks.

(i) City Services. The Court will

doubtless hear a considerable quantity of testimony from

both sides regarding the nature and extent of various city

services in the black areas. This is not a case in which

the "streets and sidewalks, sewers and public recreational

facilities provided by the town for its black citizens are

Dl

clearly inferior to those which it provides for its white

citizens," Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d at 623 (emphasis added),

or one in which the City has evidenced "inexcusable neglect

of black interests'.Id. Instead, the evidence in this case

will show good faith efforts to extend public services to

both black and white. A number of serious drainage problems

exist in many sections of Mobile, including several black

areas; the City has attempted and is attempting in good

faith to remedy such problems inherent in a low-lying area

such as Mobile. The evidence will further reflect that

street paving, maintenance, and repair and cleaning and the

like--to the extent that those activities are conducted by

the City rather than by private do¥slopersss ~=ois performed

by the City of Mobile in a non-discriminatory fashion. The

evidence will further reflect that in several instances of

unpaved streets in black neighborhoods, the condition is due

to the fact that the cost of paving non-~thoroughfare streets

in Mobile is normally assessed to abutting property owners,

and that they had been unable or unwilling to be assessed

for street paving. As Judge Johnson has noted, that unwill-

ingness or inability to sustain a paving assessment does not

rise to constitutional levels:

The evidence...reflects that the reason

that a larger percentage of the white resi-

dents are residing in houses fronting paved

streets is due to the difference in the re-

spective landowners' ability and willingness

26

Not all paving of streets in the City of Mobile is per-

formed by the City with City funds. A significant amount of

street construction is performed by real estate developers

in the construction of new subdivisions. There is no allega-

tion of any improper complicity between the City and such

developers with respect to such street paving.

25.

to pay for the property improvements.

This difference in the paving of streets

and the establishment of sewerage and

water lines does not constitute racially

discriminatory inequality. The equal pro-

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States

was not designed to compel uniformity in

the face of difference.

Hadnott v. City of Prattville, 309 F.Supp. 967, 970 (M.D.

Ala, 1970).

To the extent {if at all) that a difference in

quality of city services exists, it is in part attributable

to vandalism of public property which, the evidence will

show, is significantly worse in black areas of town. To

the extent that vandalism in black sections causes a differ-

ence in the quality of services, the difference is not a

constitutional deprivation. Beal v. Lindsey, 468 F.2d 287,

290-01 (2d Cir.1972).

It is also worth noting that, to the extent there

is any inequity in the respective quality of city services

in black and white areas, plaintiffs have a direct pin-

point remedy in a suit for equalization under Hawkins v.

Town of Shaw, Miss., 437 F.2d 1286(5th Cir.1971), aff'd

on rehearing en banc, 461 F.2d 1171(5th Cir.1972), at

least to the extent that any difference in service levels

was purposeful. Washington v. Davis, U.S. , 4b

Smtr?

U.S.L.W. 4789, 4793 n.12 (U.S. June 7, 1976). To the extent

that any such inequity may be of significance to Mobile's

black citizens, the remedy might more appropriately be the

limited one of equalization rather than the severe one of

changing the entire form of the city government. Whitcomb

v, Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 160(1971); Note, 87 HARV.I.REV,

. ol »

1851, 1859 n.50(1974).

(ii) Boards and Commissions. Plaintiffs

will probably introduce evidence reflecting that blacks are

not represented on the City's various boards and commissions

in proportion to their percentage of the population. Defend-

ants concede that to be so, and there is no dispute over that

fact.

The discretionary appointments to city boards and

commissions are, as a matter of comity, either entirely

beyond federal judicial review, or very nearly so. Mayor

of Philadelphia v. Educational Equality League, 415 U.S.

605, 614-15(1974) (suit to insure bi-racial array of city

appointees); James v. Wallace, F.2d (3th Cir.

June 21, 1976) (suit to compel Governor of Alabama to appoint

more blacks). That being so, back-door judicial relief in

the form of a finding of lack of responsiveness based on

appointments seems particularly inappropriate. There are,

in any event, several black board members, and an increase

in their number cannot be instantaneous under any form of

government. The Commissioners are ''powerless to appoint

blacks to boards and commissions until the appearance of

vacancies". Yelverton v. Driggers, 370 F.Supp. 612, 619

(M.D. Ala. 1974). Additionally, the overwhelming majority

of these boards are simply irrelevant to the ''particularized

needs of blacks.

(iii) Disparity in Employment Statistics.

The city employment statistics expected to be introduced

will indicate a disparity between the percentages of white

and black employed on the one hand, and their respective

2

percentages in the population on the other.

The City of Mobile is limited in its ability to

employ those whom it might otherwise choose; strictures are

placed upon its hiring freedom by the fact that the Mobile

County Personnel Board (which is not a department of the

City) presents employment lists to the City from which

hiring is effected.

To the extent that there might have been impropri-

eties in hiring, plaintiffs have and have had a direct remedy

in this Court, in the form of lawsuits directly aimed at

remedying those violations rather than at a change in the

form of government.

Additionally, the Supreme Court has recently noted

in Washington that mere disproportionate hiring by the city,

without more, does not indicate a Constitutional violation.

U.S, at , 44 U.8.1L.W, at 479%. ‘that being so, it

mt p——

seems inappropriate to find a constitutional violation by

a back~door approach which instead holds the form of govern-

ment unconstitutional upon the theory that there is a dis-

parity in employment which is, in itself, constitutional.

A holding changing the form of government ought not to be

based upon such gossamer, backward logic.

In sum, there has been no significant, general

"lack of responsiveness'' of the city government in Mobile in

recent years to the particularized needs of blacks.

(¢) No "tenuous state policy underlying the

27 oe! : ‘

See Allen v. City of Mobile, Civ. No. 5409-69-P(S.D.

Ala.) ; Anderson v. Mobile County Commission et al., Civ. No.

7383-72-0(8. 0. 41=.7.

«28

preference for multi-member or at-large districting'.

There is no clearcut state policy either for or against

multi-member districting in the State of Alabama, considered

as a whole; hence, the "ambivalent state policy in this re-

gard must be considered as a neutral factor in our consid-

eration’. Yelverton v. Driggers, 370 F.Supp. at 619.

Just as in Yelverton, however, it is appropriate

to look at the state policy, as expressed by the state Yag~

islature, with specific reference to Mobile.

A summary of each form of government obtaining

in the City of Mobile since prior to Alabama statehood is

attached as Appendix A. As that Appendix suggests, the gov-

ernment of the City of Mobile throughout its history for

more than a century and a half has contained, at least in

part, some multi-member feature. For sixty-five years the

City Commission form of government with at-large elections

has been in effect in Mobile.

Therefore, whatever the policy of Alabama has been

with respect to other municipalities in the state, its mani-

fest policy as to the City of Mobile has been, for a sig-

nificantly long period, multi-member districting.

(d) No "existence of past discrimination in

general precludes the effective participation in the election

1" system. The City of Mobile in this litigation candidly ad-

mits at the outset that in the past, there were significant

28 \10ng the lines of the "intensely local appraisal"

suggested in White, it may be noted that Mobile has long been

considered a political island outside the mainstream of Ala-

bama politics. That fact makes particularly appropriate the

consideration of the policy of the City itself regarding

these districts, in addition to that of the State as a whole.

~29.

levels of official discrimination by the City. There is,

of course, no doubt about that as Mobile's history in this

regard is similar to that of Southern cities generally.

The question, however, is not whether there was

discrimination in the City's history [admittedly there was],

but whether that discrimination today ''precludes the effec-

tive participation in the election system''. Accord, Bradas

v. Rapides Parish Police Jury, 508 F.2d 1109, 1112(5th Cir.1975).

The history of discrimination does not presently

preclude effective participation in the political system.

Every phase of the processes of registration, voting, qual-

ification, and running for a position on the City Commission

is just as open to blacks as to whites. Past discrimination

does not ''preclude effective participation' in Mobile City

political affairs, nor in, for example, legislative races

where blacks have been elected. As in the Fairfield case,

the plaintiffs cannot prove ''that past discrimination pre-

cludes the effective participation by blacks in the election

system'". Nevett v. Sides, F.Supp. SUN. Du Ala,

June 11, 1976). To the extent that blacks do not register,

vote, or run for office to the same degree as whites, it is

: a product of their own choice in the matter.

Virtually every Southern city or county (and many

Northern ones) has a sad history of racial discrimination;

Mobile is not unusual in that respect. The concern is with

present facts; in this case we should avoid if possible a

result controlled by "legal standards...heavily weighted in

favor of past events'. Yelverton v. Driggers, 370 F.Supp.

at 619.

~30~

(e) Summary of ''Primary' Factors. It is there-

fore seen that, for whatever value the Zimmer criteria may

be after Washington, none of the four "primary" criteria of

Zimmer are present in this case.

Even under Zimmer, these negative findings

should mandate judgment for defendants. However, to complete

the record, the Court may wish to make findings herein on the

"enhancing'' factors.

2. '"Enhancing'' Factors.

(a) Large Districts. The multi-member dis-

trict in this case constitutes the City of Mobile as a whole.

As Judge Pointer ruled in the Fairfield case, "the election

district must be considered 'large', at least in a relative

sense. The district is as large as it can be'. Nevett wv.

Sides, F.Supp. (N.D. Ala. June 11, 1976). The

same is obviously true in Mobile.

However, the district in Chavis which passed

constitutional muster was much larger than Mobile, contain-

ing 300,000 voters in 1964. 403 U.S. at 133, n.11l. The

two at-large counties in White v. Regester were also much

larger, containing populations of 1,300,000 and 800,000.

Graves v. Barnes, 343 F.Supp. 704, 720(W.D. Tex.1972), aff'd

in part & reversed in part sub.nom. White v. Regester, 412

U.S. 755(1973). While Mobile is not 'large'" in comparison

to those districts, it is probably large enough to be con-~

sidered "large" within the meaning of this enhancing factor.

(b) Majority Vote Requirement. Under Act 281,

a majority vote is required for election.

(c) Anti-Singleshot Voting Provisions. There

“31

. is in Act 281 no "anti-singleshot'" voting provision; neither

is there one in its current codification [ALA.CODE tit. 37,

§89 et.seq.] or in Act 823. ? In a sense, as Judge Pointer

held in the Fairfield dase, the numbered-position provision

of Act 823 {[ov, iE Act 823 is invalid, tit. 37, §94] may

have to some extent the same result. At least in part, then,

the practical result of an anti-singleshot provision obtains

in Mobile.

(d) Lack of Residence Requirement. Act 281

does not contain any provision requiring that any commis-

sioner reside in any portion of town. If Act 823 is valid,

a residence requirement would be at a minimum anomalous and

probably even unconstitutional, as it would require that the

Commissioner in command of each particular function (for

29An "anti-singleshot' provision obtained in all city

elections in Alabama from 1951 to 1961:

A ballot commonly known or referred to as

"a single shot'" shall not be counted in

any municipal election. When two or more

candidates are to be elected to the same

office, the voter must express his choice

for as many candidates as there are places

to be filled, and if he fails to do so, his

ballot, so far as that particular office is

concerned shall not be counted and recorded.

ALA.CODE tit. 37, §33(1), repealed September 15, 1961.

Judge Pointer held that:

(3)There is no anti-single shot voting pro-

vision since candidates run for numbered

positions. The numbered position approach

does have some of the same consequences how-

ever as an anti-single shot, multi-member

race; because a cohesive minority is unable

to concentrate its votes on a single candidate.

The numbered position approach does, however,

eliminate the problem caused when a minority

group 1s unable to field enough candidates

in anti~single shot, multi-member races.

Nevett v. Sides, _ F.Supp. at C{R.D. Ala. June 11, 1974),

Sh s—————

-32-

example, Public Safety) reside in and be elected from one

particular side of town, accountable only to one third of

the population notwithstanding jurisdiction over the entire

City.

If Act 823 is not valid, on the other hand,

similar problems could likely ensue. In that event, the

majority of the Commissioners could apparently assign what-

ever tasks it wanted to the third commissioner, ALA.CODE tit.

37, §§95-96, or even perhaps no administrative functions,

leaving the district which he represents effectively unrep~

resented in the administrative affairs of the City. There

are no apparent, explicit state law limits upon such a

practice contained in the optional commission form of gov~

ernment statute. ALA.CODE tit. 37, §89 et.seq.

In sum, it appears that the enhancing factor

dealing with residence requirements is intended to be con~

sidered in cases involving city councilmen or the like

with identical duties, and is irrelevant to cases which,

like this, involve the city commission form of government.

If this factor should be deemed relevant, however, there

is none.

(e) Summary of Findings on "Enhancing Factors,"

and "Agcregate' of All Factors. There are in this case no

"primary" factors present, but each relevant "enhancing"

factor is present, for whatever value the Zimmer factors

may have after Washington.

Even prior to Washington, under Zimmer criteria

alone, defendants would be entitled to judgment in this case.

Since none of the "primary' factors are present, plaintiffs

“33

: cannot be said to have proved an "aggregate'' of the Zimmer

factors, and their claim must therefore fail on that ground

alone, even under cases formulated prior to Washington v.

Davis.

But there are also other considerations which,

for purposes of completeness of the record, merit consideration.

VI. DEFENSES AND OTHER PERTINENT CONSIDERATIONS

A. Traditional Constitutional Tolerance of Various

Forms of Local Government. It may be appropriate to note

that as a matter of constitutional law, the more "local" a

government, the greater the leeway which has been given to

it in constitutional/political cases. See, e.g., Abate v.

Mundt, 403 U.S. 182, 185(1971). The Supreme Court has been

particularly alert to avoid inflexible federal limitations

upon the form of local government:

Viable local governments may need many

innovations, numerous combinations of

old and new devices, great flexibility

in municipal arrangements to meet chang-

ing urban conditions. We see nothing in

the constitution to prevent experimentation.

Sallors v, Bd, of Educ;, 387 U.S. 105, 110~-11(1967). The

city commission form of government was itself an experiment,

the evidence reflects; doubtless every form of local govern-

ment was once in some degree experimental. To the extent

that it is possible, cities should be allowed some measure

of freedom in their attempts to solve or mitigate govern-

mental problems. The Constitution should be flexible enough

to allow that experimentation:

Frequent intervention by the Courts in

state and local electoral schemes would

3 -

seem to run counter to the Supreme

Court's...concern for innovation

and experimentation at the local level.

Note, 87 HARV.L.REV, 1851, 1860(1974).

The second, third and fifth defenses raised by defend-

ants reflect this policy of comity and federalism; oT as in

Mayor of Philadelphia, "[tlhere are...delicate issues of

federal~state relationships underlying this case'. 415 U.S.

at 615. The federalism problem is made most acute by the

fact that, if this Court were to impose single-member dis-

tricts, in all probability the Court would have to order

that the very form of government be changed, from a commis-

sion form to another and different form, such as mayor/council.

B. Necessity for Change in Form of City Government if

Single-Member Districts Ordered. As enacted in 1911, as

already noted, the Commissioners of the City of Mobile appor-

tioned among themselves the duties of City government. In

1965, Act 823 was passed, providing that Commissioners be

elected to specific posts for specific jobs.

As previously discussed, since plaintiffs have not pre-

vailed under either Zimmer alone or Zimmer as modified by

Washington, it is not necessary that a Three-Judge District

Court be convened to consider the validity of Act 823.

Whether or not Act 823 is valid under §5, the Procrustean

imposition of single~-member districting, as already noted,

would bring on absurd and unconstitutional results caused

3lrechnically, these federal/state relations cases do

not involved the''political question' doctrine, because that

doctrine concerns relations between co-ordinate branches of

the federal government. Jackson, The Political Question Doc-

trine: Where Does It Stand After Powell v. McCormack, O'Brien

v. Brown, and Gilligan v. Morgan? 44 U,COL.L.REV. 477,508-510 Twa

(1973),

“35

by the fact that city commissioners, unlike aldermen or

councilmen, each perform different administrative functions.

In order to avoid such an anomaly attendant on the imposition

of single-member districting upon the commission form of gov-

ernment, the Court would have to change the form of the City

government. The problem is fraught with difficulty, and

would clearly militate against the imposition of single-

member districting as a remedy even assuming that plaintiffs

had prevailed on the merits.

C. "Swing Vote". Testimony in this case will show

that blacks in Mobile not infrequently comprise a "swing"

vote able to decide close elections to a degree significantly

beyond their percentage in the population. While the actual

effect is local in nature, it is a phenomenon which is not

uncommon in multi-member district situations. E.g.,Lipscomb

v. Wise, 399 F.Supp. 732, 793(N.D. Tex. 1975) (multi-member

election permitted Mexican/Americans ''as a group to operate

in a 'swing-vote' manner and give them opportunity they

might not otherwisehave had"). As one legal CommenEatoY

has written:

A group of voters that influences many

legislators in a small way is not in-

herently less desirable than a group

that has a large impact on one legisla-

tor. Indeed, when other voters in a

district in which the blacks constitute

a minority are in a state of political

equilibrium, it may be that the black

group will wield political clout dis-

proportionately large for its numbers.

Carpeneti, Legislative Apportionment: Multi-Member Districts

and Fair Representation, 120 U.PA.L.REV, 666,692-93(1972).

The swing vote factor is entitled to evidentiary weight in

support of multi-member districting.

«35~

D. Banzhaf Theory. Defendants also expect to offer

proof upon the statistical propriety of the Banzhaf theory,

explained fully in Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 145 n.

23(1971) ; Banzhaf, One Man, ? Votes: Mathematical Analysis

of Voting Power and Effective Representation, 36 GEO. WASH.

L.REV. 808(1968); Banzhaf, Multi-member Electoral Districts--

Do They Violate the '"One Man, One Vote'' Principle, 75 YALE

L.J. 1309(1966). The thrust of the theory is that if votin

power is defined as the chance that a voter will be able to

cast a decisive vote, then individual voters in multi-member

districts have more voting power than do individual voters

in single-member districts. The theory is purely a statis-

tical one, necessarily severed from the hard facts of poli-

tical life, and is separate and distinct from the issue

respecting the black vote as a swing vote, supra, which is

factually based upon the Mobile political experience. The

Supreme Court in Chavis declined to base its decision on the

Banzhaf theory, noting that it was ''theoretical', 403 U.S.

at 145, but did not deny that the theory was entitled to

some (if not decisive) evidentiary weight. The theory is

entitled to be accorded some evidentiary weight in favor of

the retention of multi-member districting in the City of

Mobile.

E. City-wide Perspective. Evidence to be adduced by

defendants will suggest that the City of Mobile has a legit-

imate governmental interest in having commissioners with a

city-wide, non-parochial view of city affairs. The evidence

will further suggest that such a city-wide perspective would

be in significant measure lost with the imposition of single-

“37

member districting. The city-wide perspective has been found

to be a legitimate governmental interest by both courts and

commentators, In Lipscomb v. Wise, the District Court found

a "legitimate governmental interest" in having some city

council members with a "city-wide view on those matters which

concern the city as a whole", 399 F.Supp. at 795, and suggested

correctly that [bl]udget and services certainly do not stop at

district boundaries'. Id, at n.15. One commentator has

similarly written that:

The district wide perspective and alle-

giance which result from representatives

being elected at-large, and which enhance

their ability to deal with district wide

problems, would seem more useful in a

public body with responsibility only for

the district than in a statewide legislature.

Note, 87 HARV.L.REV, 1851, 1857 (1974).

The desire of the City for a city-wide geographic per-

spective is a factor entitled to some evidentiary weight

in this case in favor of the present form of government.

F. Increased Polarization and Possible "Minority

Freeze-out'' Under Single-Member Plan. Defendants expect to

adduce testimony showing that if a single-member plan of

city government representaticn were adopted, the degree of

racial /political polarization would in all likelihood at

least stay at the same level, and perhaps increase, with the

result that the white majority in the City would likely be

able to elect a majority of the Commission. That, along with

the fact that a single '"black' Commissioner and each "white"

Commissioner would in a single~member situation probably

espouse narrow, parochial views of principal interest to

constituents of their single, racially homogeneous districts,

® ~35- ®

would cause highly visible clashes in city government which,

inevitably, would be seen as principally racial in nature.

The probable result would be a virtual freeze-out of the

single black Commissioner and his constituents. The same

problem was found by the Court in Lipscomb:

The Court is particularly concerned with

the prospect of district sectionalism

which usually occurs in an exclusive

single~-member district plan. The Court

is convinced that no matter how many

single-member districts are drawn in

Dallas, black voters in all probability

would never elect more than 25% of city

council so long as the present pattern of

voting exists. With all single~-member dis-

tricts and the present voting pattern, it

would be possible for a majority of council

to "freeze out" this 25% and for all practi-

cal purposes ignore minority interests.

399 F.Supp. at 795, n.1l6 (emphasis in original). The sig-

nificant possibility of such a minority freeze-out is en-

titled to evidentiary weight against a single-member districting

plan. pe

G. Single-Member Districting and New Constitutional

Problems. Single-member districting would import into Mobile

city government two new and different constitutional problems

which the City has so far been able to avoid: reapportion-

ment and gerrymandering.

1. Reapportionment. One very significant factor

in favor of multi-member districting is that, with the ex-

ception pro tanto presented by the Banzhaf theory, multi-

member districting without a residence requirement presents

perfect numerical apportionment. Regardless of where a

voter lives, his vote will exactly equal every other vote,

even up to the end of each decade when post-census population

shifts have malapportioned most single-member districts.

«3485

Because of the notorious unwillingness of governmental bodies

32 there is in Alabama and elsewhere to apportion themselves,

a significant chance that a United States District Court

would ultimately be called upon to reapportion the City.

The possibility or even likelihond of that decennial neces-

sity certainly should give pause when considering whether to

impose single-member districting as a constitutional require-

ment. That possibility is properly to be considered when

determining the propriety of single-member relief.

2. Gerrymandering. A multi-member district does

not and cannot present the problem of gerrymandering of in-

ternall> district lines. The imposition by this Court of

single-member districting would for the first time in many

‘decades introduce into Mobile the problem of gerrymandering.

Whether dttmarely brought into Federal Court as a constitu-

tional matter or not, see Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S.

52(1964), the problem would be a significant one. And it

is entertwined with the problem of reapportionment, since

the difficulty of political line drawing after each decennial

census inevitably suggests inaction by incumbent officeholders.

The related problems of reapportionment and gerry-

: mandering have so far not been imported into the City of

Mobile. The imposition of single~-member districting by

this Court would do so for the first time in recent history.

32 :

For the record of Alabama in that respect, see Stewart,

Reapportionment With Census Districts: The Alabama Case, 24

ALA. L.REV., 693, 694 n.56(1972). |

It is of course always possible for any city to attempt

to draw its perimeter so as to include or exclude certain per-

sons, see Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 399(19560), but a

multi-member district by definition has no internal district

lines,

fi (=

That is a factor of evidentiary weight tending against the

imposition of single-member districting.

H. Flexibility of Federal Equitable Relief. Even if

the plaintiffs were to have made out a claim for equitable

relief, that would not necessarily entitle them to a change

in the form of government, or to the imposition by this

Court of single-member districts. Chavis makes clear that

the Court, upon finding for plaintiffs in a case of this

nature, ought to attempt if possible to remedy the wrong

by action less drastic than the wholesale imposition of

single-member districting:

[I]t is not at all clear that the remedy

is a single-member district system with

its lines carefully drawn to ensure rep-

resentation to sizeable racial, ethnic,

economic or religious groups and with

its own capacity for overrepresenting

parties and interests and even for per-

mitting a minority of the voters to con-

trol the legislature and government of a

state...

Even if the District Court was correct

in finding unconstitutional discrimination

against...[plaintiffs,] it did not explain

why it was constitutionally compelled to

disestablish the entire county district and

to intrude upon state policy any more than

necessary to ensure representation of ghetto

interests. The Court entered judgment with-

out expressly putting aside on supportable

grounds the...possiblity that the Fourteenth

Amendment could be satisfied by a simple re-

quirement that some of the at-large candidates

each year must reside in the ghetto.

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 160(1971).

Certainly, even if plaintiffs prevail in the in-

stant case, relief on less-than-a wholesale scale would

accord with the precepts of equity, encompassing '[f]lexi-

bility rather than rigidity". Hecht v. Bowles, 321 U.S.

321, 329~30(1944). Judge Johnson, for example, in an

eT

analogous but pre-Washington case, upon finding for plain-

tiffs, merely ordered periodic reports to be made upon the

issues of trial (street paving, ete), upon the ground that

the City was making good-faith efforts and "the applicable

legal standards are heavily weighted in favor of the consid-

eration of past events'. Yelverton v. Driggers, 370 F.Supp.

at 619. In sum, single-member districting is not necessarily

the proper equitable remedy even if a constitutional vio-

lation exists.

VII. AVAILABLE POLITICAL REMEDY

While the availability of a political remedy for plain-

tiffs' alleged wrongs by no means mandates abstention, iL is

certainly worth consideration for whatever significance it

may have,

A. Legislative Remedy. The form of city government

presently obtaining in Mobile was, of course, passed by the

Alabama Legislature in 1911. The evidence in this case

will show that under the prevailing custom in the Legisla-

ture called "legislative courtesy', that body will enact

virtually any local government provision agreed upon by the

local delegation.

The Alabama Legislature is elected under a court-

ordered plan approved by the Supreme Court, from single-

member districts of near-perfect numerical apportionment.

Several of the members of the Mobile legislative delegation

are black and, plaintiffs would no doubt admit, represent

345ims v. Amos, 336 F.Supp. 924(M.D. Ala. 1972) (3-judge

court), aff ¢,..-409 1,8. 942(1973).

2li2 «

any 'particularized interests' of Mobile blacks in that

body. In the course of the never-ending process of munici-

pal government experimentation in Alabama and elsewhere, it

does not seem inappropriate to suggest that ''relief' from a

legislatively-imposed government may well be available to

35

plaintiffs and their class from the legislature.

B. Abandonment. There is also available to the citi-

zenry of Mobile a state procedure styled "abandonment',

pursuant to which the voters can abandon the commission form

of government and return to the aldermanic system obtaining

prior to the adoption of the commission form of government.

ALA.CODE tit. 37, §120 et.seq. That abandonment may be

initiated by signatures of only three percent of the regis-

tered voters of the City. Id. at § 120. It may be noted

that the aldermanic form of government obtaining in Mobile

prior to 1911 had a residence requirement for councilmen,

so that a return to this form of government would provide

the very relief (residence requirement) the imposition of

which the Chavis Court said should be considered as quite