Florida v. Board of Control Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of the State of Florida

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1951

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Florida v. Board of Control Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of the State of Florida, 1951. 6de37a03-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0706a542-5880-48bd-848f-74ae75de8a06/florida-v-board-of-control-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-the-state-of-florida. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

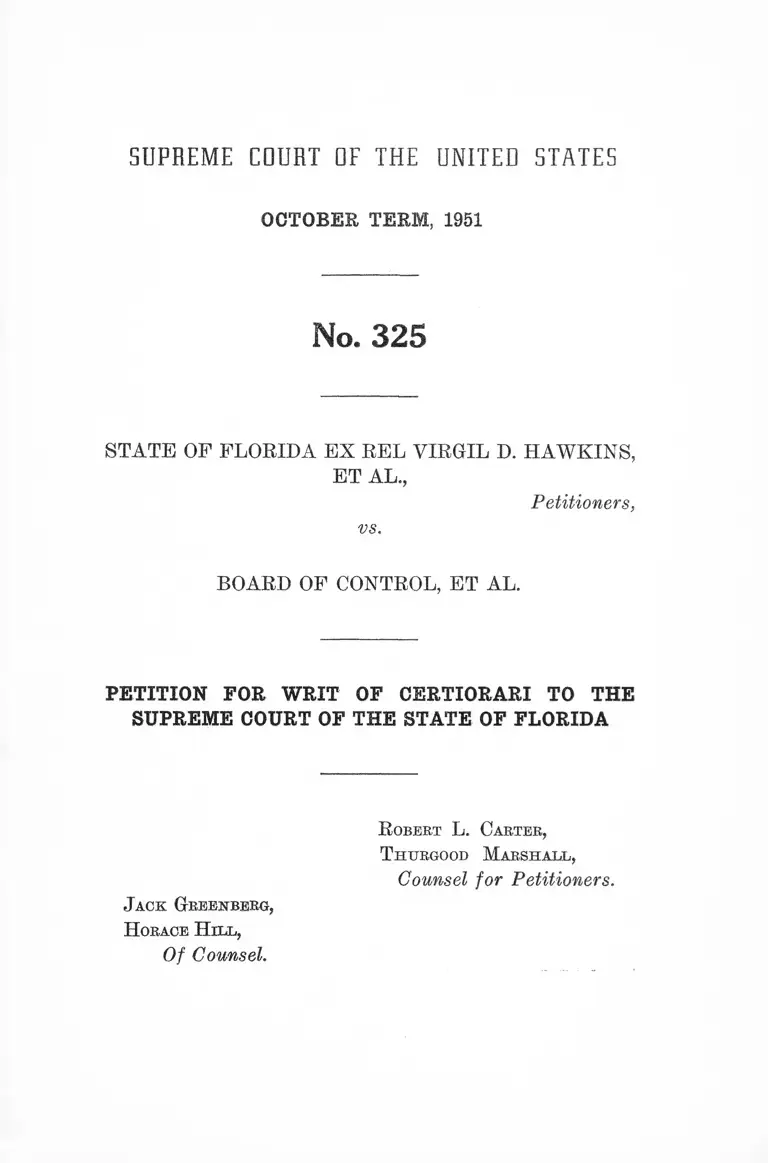

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1951

No. 325

STATE OF FLORIDA EX REL VIRGIL D. HAWKINS,

ET AL.,

vs.

Petitioners,

BOARD OF CONTROL, ET AL.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood M arshall,

Counsel for Petitioners.

J ack Greekberg,

H orace H il l ,

Of Counsel.

OCTOBER TERM, 1951

SUPREME EOURT DF THE UNITED STATES

No. 325

STATE OF FLORIDA EX EEL VIRGIL D. HAWKINS,

ET AL.,

Petitioners,

vs.

BOARD OF CONTROL, ET AL.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA

To the Honorable, the Chief J%istice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the

United States:

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgments of the Supreme Court of Florida, entered in

the above-entitled cases on June 15, 1951.

Opinions Below

Opinions of the Supreme Court of Florida were entered

on August 1, 1950, and on June 15, 1951. The August 1,

2

1950 and June 15, 1951 opinions in Stale ex rel Hawkins v.

Board of Control are reported in 47 So. 2d 608, (R. 25) 1

and in 53 So. 2d 116, respectively (R. 40); in State ex rel

Boyd v. Board of Control, 47 So. 2d 619, and 53 So. 2d 120,

respectively; in State ex rel Lewis v. Board of Control, 47

So. 2d 617, and 53 So. 2d 119; in State ex rel Finley v.

Board of Control, 47 So. 2d 620 and 53 So. 2d 119; in State

ex rel Maxey v. Board of Control, in 47 So. 2d 618, and 53

So. 2d 119.

Jurisdiction

Tlie Supreme Court of Florida on June 15, 1951, denied

petitioners’ motions for peremptory writs of mandamus and

for further relief as provided in its orders of August 1,

1950 (R. 40). Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1257(3). At each and

every stage of these proceedings, in the motions for

alternative writs of mandamus, in the alternative writs

themselves, in the motions for peremptory writs of man

damus filed on January 19, 1950 (R. 24), and in the motions

for peremptory writs of mandamus and for further relief

filed on May 16, 1951 (R. 39), petitioners grounded their

claims in the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Throughout these proceedings, petitioners have raised,

relied upon and preserved the federal questions which

are brought before this Court in this petition.

Questions Presented

1. Can the State refuse to admit petitioners to the Uni

versity of Florida solely because of race and color for the

1 All record citations are to the record in the Hawkins ease since the

printing of the other records was not completed at the time this petition

was sent to the printers. The only difference in the cases are the names

of petitioners.

3

pursuit of graduate education and training in law without

violating petitioners’ rights to the equal protection of the

laws as guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.

2. On the basis of a resolution of the Board of Control

ordering the establishment at the Florida A & M College

for Negroes of the courses which petitioners seek to pursue

and which provides for petitioners’ admission to the Uni

versity of Florida on a segregated basis in the event the

courses desired are not available at Florida A & M College

at the time petitioners seek to enroll therein, especially

where the answers filed conclusively show that the courses

ordered established at Florida A & M College were not in

fact in actual operation, can the State of Florida avoid its

constitutional obligation of immediately admitting peti

tioners to the University of Florida.

Statement

The cases of State ex rel Hawkins, State ex rel Lewis,

State ex rel Boyd, State ex rel Finley and State ex rel

Maxey v. Board of Control were brought in the court below

as separate and independent causes. All five cases involve

the same questions and were disposed of in the same manner

in the court below. One petition covering all five cases,

therefore, is being filed in this Court.

On April 4, 1949, petitioners made due and timely appli

cation for admission to the University of Florida, a public

institution maintained and operated by the State for the

higher education of its citizenry. Virgil Hawkins and Wil

liam T. Lewis applied for admission to the School of Law;

Rose Boyd for admission to the School of Pharmacy; Oliver

Maxey for courses leading to a graduate degree in Chemical

Engineering; and Benjamin Finley for courses leading to a

graduate degree in agriculture. As of the time of their

4

respective applications, and as of now, petitioners were and

are fully qualified in every legal respect for admission to

the University of Florida. Moreover, they would have been

admitted without question but for the fact that they are

Negroes.

Their applications were referred to the Board of Control,

respondents here, which governs and controls the entire

university system of the State of Florida. On May 13, 1949,

petitioners met with the Board of Control. At this meeting

they were advised that the only state institution in Florida

where the courses of study they desired could be pursued

was at the University of Florida, but that in view of the

laws of the state they could not be admitted to the Uni

versity of Florida since it was maintained exclusively for

white persons. The Board offered to pay petitioners’ tui

tions to institutions of their choice outside the state (R.

16-17).

Whereupon, petitioners instituted the instant action by

filing petitions for alternative writs of mandamus in the

Supreme Court of Florida (R. 1). These petitions were

granted on June 10, 1949 (R. 4). Respondents’ motions to

quash were denied on December 8, 1949 (R. 9), and on

January 7, 1950 the respondents filed their answers (R. 9).

Respondents admitted that petitioners were refused ad

mission to the University of Florida solely because they are

Negroes. It was admitted that at the time of petitioners’

applications that the University of Florida was the only

state institution offering courses in law, graduate agricul

ture, pharmacy and chemical engineering. The answers

further alleged that authorization had been given by the

Board of Control, in the.form of a resolution dated Decem

ber 21, 1949 for Florida A & M College for Negroes to

provide the courses of study which petitioners sought to

pursue (R. 21). The Board resolution recited that if the

courses desired were not available at Florida A & M College,

5

when petitioners made application for admission thereto,

and in the event the offer of out-of-state aid to petitioners

should be held not to satisfy the state’s constitutional obli

gations, petitioners would be admitted temporarily to the

University of Florida on a segregated basis until such time

as courses in question became available at Florida A & M

College (R. 22).

On January 19, 1950, petitioners filed motions for per

emptory writs of mandamus notwithstanding respondents’

answers. The court held these petitions to be in the nature

of demurrers in that they admitted the truth of respondents’

allegations of fact. The court held that for the purpose of

decision on petitioners’ motions for peremptory writs of

mandamus notwithstanding respondents’ answers, the

allegation by the Board of Control that as of December 21,

1949, it had ordered the establishment of Schools of Law,

Pharmacy, Graduate Agriculture and Chemical Engineer

ing at Florida A & M College and had ordered reactivation

of the necessary effort to secure equipment and personnel

and offered to temporarily admit petitioners to the Uni

versity of Florida, on a segregated basis, until such time as

these schools were actually in operation at the Negro Col

lege sufficiently satisfied the state’s constitutional obligation

to furnish equal educational opportunities (R. 32-38). The

court refused, however, to enter a final order and retained

jurisdiction of the cases in order to permit either peti

tioners or respondents to come before the court at some

later date to seek whatever further relief might then be

warranted (R. 38).

Petitioners reapplied to the University of Florida for the

courses desired on August 7, 1950. On May 16, 1951, not

having been admitted to or enrolled in any institution for

the courses desired, petitioners filed motions for peremp

tory writs of mandamus and for further relief in accord

6

ance with the court’s opinion of August 1, 1950. On June

15, 1951, these motions were denied (R. 40). Whereupon,

petitioners bring the causes here.

Specification of Error

1. The court erred in refusing- to grant petitioners’

motions for peremptory writs of mandamus filed on Jan

uary 19, 1950 when respondents’ answers clearly showed

that courses petitioners desired were available only at the

University of Florida.

2. The court erred in refusing to grant petitioners’

original motions for peremptory writs of mandamus not

withstanding respondents’ answers where the December 21,

1949, resolution, on which respondents rely, clearly showed

that no courses in law, chemical engineering, graduate agri

culture and pharmacy were actually available or in opera

tion at Florida A & M College for Negroes.

3. The court erred in refusing to issue a decree ordering

petitioners immediate admission to the University of

Florida subject only to the same rules and regulations

which are applicable to all other persons.

4. The court erred in refusing to grant petitioners ’ subse

quent motions for peremptory writs of mandamus and for

further relief filed in May 1951 in view of the fact that

between the date of its opinion on August 1, 1950 and the

date of the filing of petitioners’ motions on May 16, 1951,

petitioners had not been provided with educational oppor

tunities of any nature while the courses they were qualified

to pursue were being offered white students at the Univer

sity of Florida.

Reasons for Allowance of the Writ

1. The December 21, 1949 resolution of the Board of

Control, which the Florida Supreme Court held to afford

7

petitioners equal protection of the laws, reads in part as

follows:

. . there is hereby established, at the Florida Agri

cultural and Mechanical College for Negroes, schools

of law, mechanical engineering, agriculture at graduate

level and pharmacy at graduate level; and qualifica

tions for admission to said courses shall be the same as

those required for admission to said courses at other

State institutions of higher learning in the State of

Florida; . . .

“ . . . efforts to acquire the necessary personnel,

facilities, and equipment for such courses be re

activated and diligently prosecuted, with the view of

installing said personnel, facilities, and equipment for

such courses at the Florida Agricultural and Mechani

cal College for Negroes, at Tallahassee, Florida, at the

earliest date possible, thereby to more fully comply

with the constitution and laws of the State of Florida;

and that, in the meantime, and while diligent prepara

tion is being made to physically set up said schools and

courses at the “ Florida Agricultural and Mechanical

College for Negroes, at Tallahassee, Florida, further

effort to be made to arrange with said applicants for

out-of-state scholarships or other arrangements agree

able to them, equal to their reasonable individual needs

and affording them full and complete opportunity to

obtain the education for which they have applied,

where obtainable, at institutions other than Florida

state operated institutions of learning for white stu

dents, and under circumstances and surroundings fully

as good as may be offered at any State operated insti

tution of higher learning in the State of Florida;

“ . . . in the event the court should hold that the fore

going provisions are insufficient to satisfy the lawful

demands of said applicants, that temporarily, and only

until completion of such acquisition of personnel, facili

ties and equipment for installation at the Florida Agri

cultural and Mechanical College for Negroes, at Talla

hassee, comparable to those in institutions of higher

learning of the State established for white students,

8

the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College for

Negroes shall arrange for supplying said courses to its

enrolled and qualified students at a Florida state oper

ated institution of higher learning, where said courses

may be given, and where the instructional personnel

and facilities of such institution in the requested

courses shall be provided and used for the education of

said applicants at such times and places, and in such

manner, as the latter institution may prescribe; and

the authorities of such last described state operated

institution of higher learning shall cooperate in making

such arrangements, to the end that there shall he avail

able to said students of the Agricultural and Mechani

cal College for Negroes, substantially equal oppor

tunity for education in said courses as may be provided

for white students under like circumstances. In pro

viding such education, the authorities of both institu

tions shall at all times observe all requirements of the

laws of the State of Florida in the matter of segrega

tion of the races, etc . . . ” (R. 22).

This resolution clearly shows that no courses in law,

graduate agriculture, pharmacy or chemical engineering

were actually being offered at Florida A & M College.

Hence, no reliance whatsoever could possibly be placed by

respondents on the state’s segregation laws, even assuming,

as did the court below, that the Plessy v. Ferguson, 163

U. S. 537, doctrine of “ separate but equal” governed the

disposition of petitioners’ claims. Petitioners were un

questionably entitled to admission to the University of

Florida, it being the only state institution actually offering

the courses they desired to pursue. Missouri ex rel Gaines

v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337; Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332

U. 8. 631. The decision of the court below that the resolu

tion of December 21, 1949 afforded petitioners equal pro

tection of the laws is in further direct conflict with the

9

Sipuel-ca.se where this Court held that Negro applicants

must be furnished educational opportunities as soon as such

facilities are made available to white persons.

2. The practice of any form of segregation based on race

and color at the professional and graduate school level of

state universities violates the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment, Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S.

629; McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637; Wilson

v. Board of Supervisors, 94 L. Ed. (Adv. Op.) 200; Mc-

Kissich v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (CCA 4th 1951), cert,

den. — U. S. —, June 4, 1951. Thus the approval by the

court below of the December 21, 1949 resolution, which at

best would permit petitioners ’ temporary admission to the

University of Florida on a segregated basis, is in direct

conflict with these cited cases.

It should be pointed out that in the Sweatt case, where

the segregated Negro law school was held not to afford

petitioner equal educational opportunities, that the law

school had been in operation for several years; that in the

Wilson case a Negro law school had been functioning at

Southern University in Louisiana for at least five years;

and that in the McKissick case the law school at the North

Carolina College for Negroes had been in continuous oper

ation since 1939. Yet all three schools were found inferior

to the law school operated at the main State university.

Here, on the other hand, there wasn’t even a semblance of a

law school or graduate school but merely a directive to

reactivate and diligently prosecute efforts to procure neces

sary equipment, personnel and facilities to get the desired

courses of study functioning.

3. The decision of the court below that petitioners must

first apply to Florida A & M College for Negroes, and the

courses they desire not be there available, before being

10

entitled to admission to the University of Florida is in

direct conflict with the decisions of this Court in Missouri

ex rel Gaines v. Canada, supra; Sweatt v. Painter, supra.

It is admitted that petitioners had made due and timely

application to the University of Florida. They were wrong

fully and illegally refused admission, whereas white persons

were accepted. Having proved their qualifications and the

respondents’ wrongful denial of their applications, peti

tioners were entitled to an affirmative and unconditional

decree ordering respondents to immediately admit them to

the University of Florida subject only to the same rules and

regulations applicable to all other persons.

4. The denial by the court below of petitioners’ motions

for peremptory writs of mandamus and for further relief

filed on May 16, 1951 in which it was recited that respond

ents had failed to provide petitioners with equal educa

tional opportunities was contrary to decisions of this Court

in which the question of equal educational opportunities

has been decided, Sipuel v. Board of Regents, supra; Sweatt

v. Painter, supra. The state has failed in its obligation to

furnish petitioners equal educational opportunities, and

petitioners were entitled to issuance of peremptory writs of

mandamus ordering their admission to the University of

Florida.

Conclusion

Since the decisions of the court below in these cases are

directly contrary to the decisions of this Court, as set forth

supra, it is respectfully submitted that this petition for

writ of certiorari should be granted and the causes reversed

and remanded without hearing, with instructions to the

court below that it issue a decree ordering that petitioners

be admitted to the University of Florida, forthwith, subject

11

only to the same rules and regulations applicable to all other

students.

J ack Greenberg,

H orace H ill ,

Of Counsel.

T huegood M arshall,

R obert L . Carter,

Counsel for Petitioners.

(7154)

5

t