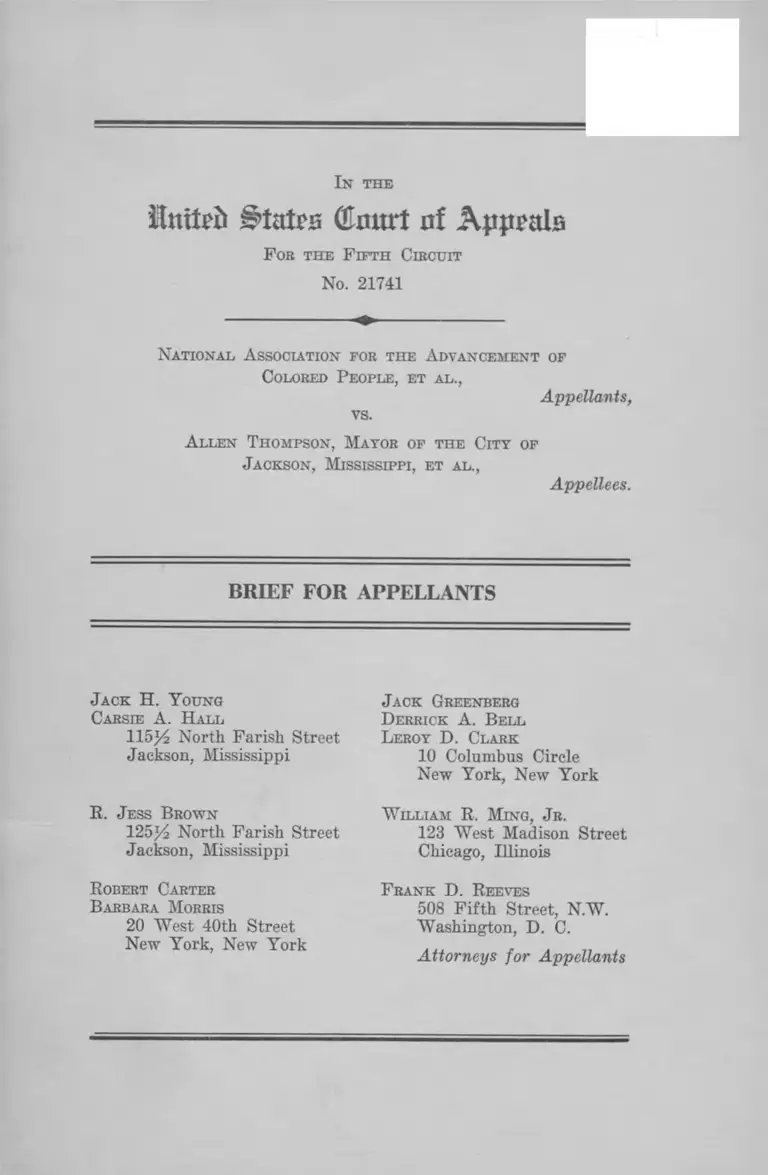

NAACP v. Thompson Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 9, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Thompson Brief for Appellants, 1964. 2534111c-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/07141a53-bfac-43a3-b1ea-5fde4657054e/naacp-v-thompson-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Umttb Btati's (Emtrt nf Appeals

F ob the F ifth Circuit

No. 21741

National A ssociation fob the A dvancement of

Colored People, et al.,

vs.

Appellants,

A llen Thompson, Mayor of the City of

Jackson, Mississippi, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Jack H. Y oung

Carsie A . Hall

115J4 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

R. Jess Brown

125J4 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

Robert Carter

Barbara Morris

20 West 40th Street

New York, New York

Jack Greenberg

D errick A . Bell

Leroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

W illiam R. Ming, Jr.

123 West Madison Street

Chicago, Illinois

Frank D. Reeves

508 Fifth Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C.

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement of the C ase........................................................... 1

A. The Case in Summary..................................... . 1

B. Racial Climate in Jackson .................................. 2

C. Appellants’ Self-Help E fforts................................. 3

1. Bi-racial Committee Proposal....................... 3

2. Mass Meetings.................................................. 4

3. Selective Buying Campaign .......................... 5

4. Voter Registration Attempts ....................... 6

D. Public Protests ...................................................... 6

1. Picketing................................. ....... .......... ...... 7

2. Testing Public Accommodations................... 8

3. Public Meetings .............................................. 9

4. Protest Marches ...... 10

5. Public Parks and Libraries .......................... 13

E. Jackson’s Response ................................................ 14

1. Preparations for Arrests .............................. 14

2. Arrests and Prosecutions.............................. 14

3. Harassment ...................................................... 16

4. State Court Injunction ...................... 17

F. Denial of NAACP Registration ......................... 17

PAGE

11

PAGE

G. Summary of the Litigation................................. 19

1. Suit Is F iled ...................................................... 19

2. Preliminary Injunction Is Denied ................. 21

3. First Appeal...................................................... 21

4. The Trial .......................................................... 22

5. The Excluded Proof ...................................... 24

6. The Trial Court’s R uling.............................. 30

Specifications of Error ...................................................... 32

A rgum ent :

I. The State’s Interference With Appellants’

Protests Were Unlawful Efforts to Enforce

Segregation, Violate Freedom of Associa

tion, and Suppress Rights to Effective Ex

pression Guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment .... ............. .................................... 33

II. Appellees’ Refusal to Register Appellant Cor

poration Not Only Is Arbitrary, Capricious

and an Unconstitutional Attempt to Exclude

NAACP From the State of Mississippi, But

Also Abridges Rights to Freedom of Ex

pression and Association, All in Violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment .......................... 42

III. Appellants Are Entitled to Obtain and the

Federal Courts Are Authorized to Grant All

the Relief Sought in the Complaint ........... 48

Co n c l u s io n ___ 52

1U

T able of Cases

page

American Optometric Ass’n v. Ritliolz, 101 F. 2d 883

(7th Cir. 1939) ................................................................. 50

Anderson v. City of Albany, — — F. Supp. (M. D.

Ga., Aug. 19, 1964) ........................................................ 48

Apex Hosiery v. Leader, 310 U. S. 469 .......................... 41

Bailey v. Patterson, 199 F. Supp. 595 (S. D. Miss.

1961) 49,50

Bailey v. Patterson, 368 U. S. 346; 369 U. S. 31; 323

F. 2d 201 (5th Cir. 1963) ..........................................6, 33, 49

Baines v. City of Danville,------ F. 2 d -------- (4th Cir.,

Aug. 10, 1964) ............................................................... 49, 50

Bank of United States v. Deveaux, 9 U. S. (5 Cranch.)

37 ....................................................................................... 42

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516................................ 39, 48

Brown v. Board of Education, 341 U. S. 483 ................... o l

Brown v. Staple Cotton Coop. Assoc., 132 Misc. 859,

96 So. 849 ......................................................................... 41

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 .................................. 37

Burns Baking Co. v. Bryan, 264 U. S. 504 ..................... 43

Butler Bros. Shoe Co. v. U. S. Rubber Co., 156 Fed. 1

(8th Cir. 1907) ............................................................... 42

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 290 .......................... 34, 37

City of Jackson v. Salter, Hinds County Chancery

Court ......................................................................... 40,17, 23

Clark v. Thompson, 206 F. Supp. 539 (S. D. Miss.

1962), aff’d 313 F. 2d 637 (5th Cir. 1963) ...................6,13

Congress of Racial Equality v. Clemmons, 323 h . 2d 54

(5th Cir. 1963) ............................................................... 49

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ............................................ 37

Cooper v. Hutchinson, 184 F. 2d 119 (3rd Cir. 1950) .... 49

IV

CORE v. Douglas, 318 F. 2d 95 (5th Cir. 1963) ...........38, 49

Crutcher v. Kentucky, 141 U. S. 47 ................................ 42

Dallas General Drivers v. Wamix, Inc., 295 S. W. 2d

873 (1956) ....................................................................... 42

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S. D. Ala. 1949) ..... 51

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 ................................ 36, 41

Denton v. City of Carrollton, Ga., 235 F. 2d 481 (5th

Cir. 1956) ......................................................................... 49

Donald v. Philadelphia & Reading Coal & Iron Co., 241

U. S. 329 ........................................................................... 43

Douglas v. City of Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157 ...........49, 50, 51

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 .........34, 35, 37, 38

Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

328 F. 2d 408 (5th Cir. 1964) ........................................ 33

Ex parte Lyons, 81 P. 2d 190 (1938) .............................. 40

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44 .......................... 35

Freeman v. Hewit, 329 U. S. 249 ...................................... 42

PAGE

Gano v. Delmas, 140 Miss. 323, 105 So. 353 ..................... 41

Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigation Committee,

372 U. S. 539 ................................................................. 36, 48

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U. S. 339 ............................. 37

Griffin v. Prince Edward School Board, 377 IT. S. 218

(1964) ............................................................................... 47

Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe R.R. Co. v. Ellis, 165

U. S. 150........................................................................... 43

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F. Supp.

649 (E. D. La. 1961) ...................................................... 51

Hanover Fire Insurance Co. v. Harding, 272 IT. S. 494 .. 43

Harrison v. St. Louis & San Francisco Ry. Co., 232

U. S. 319........................................................................... 43

Henry v. Rock Hill, 376 U. S. 776 ...................................... 35

V

Herndon v. Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Ry. Co.,

PAGE

218 U. S. 135................................................................... 43

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 342 .................................... 34

Hughes v. Superior Court, 339 U. S. 460 .....................39, 40

In the Matter of Application of Brown & Richards v.

Rayfield, 8 Race Rel. Law Rep. 425 (1963) ............... 21

Jackson v. Price, 140 Miss. 249, 105 So. 538 ................... 41

Jamison v. Alliance Ins. Co. of Philadelphia, 87 F. 2d

253 (7th Cir. 1939) ......................................................... 50

Kelly v. Page, 335 F. 2d 114 (5th Cir. 1964) ...............38, 48

Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 U. S. 77 .......................................... 36

Liggett v. Baldridge, 278 U. S. 105 .............................. 43, 47

Lineberger v. Colonial Ice Co., 17 S. E. 2d 502 (1941) .... 42

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 257 .............................. 37

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 414.................................... 34

Meredith v. Fair, 298 F. 2d 696 (5th Cir. 1962) ............. 33

Morrison v. Davis, 252 F. 2d 102 (5th Cir. 1958) ........... 50

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 .........34, 36, 38, 39, 47, 48

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 ............34, 37, 38, 39, 41, 48

New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Co., 303 U. S.

552 ............................................................................. 37,39,41

New State Ice Co. v. Liebman, 285 U. S. 262 ................... 44

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73 ........................................... 37

People ex rel. Hekanson v. Palmer, 367 111. 513,11 N. E.

2d 931 (1937) ................................................................... 43

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244................... 37

Pullman Co. v. Kansas ex rel. Coleman, 216 U. S. 56 .... 43

VI

Ready Mix Concrete and Concrete Products Company

v. Perry, 239 Miss. 329, 125 So. 2d 241 ................... 41

Rice v. Asheville Ice Co., 169 S. E. 707 (1933) ................. 41

Rosman v. United Strickling Kosher Butchers, 298

N. Y. S. 243 (1937) ......................................................... 40

Ross v. Texas, 341 U. S. 918............................................ 37

Roth v. United States, 354 U. S. 476 ................................ 36

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147...................................... 36

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U. S. 232 .... 44

Sellers v. Johnson, 163 F. 2d 877 (8th Cir. 1957) ......... 37

Shepard v. Florida, 341 U. S. 5 0 ...................................... 37

Simonetti Bros. Produce Co. v. Fox Brewing Co., 240

Ala. 91, 197 So. 38 (1940) .............................................. 42

Smith v. Allright, 321 U. S. 649 ...................................... 37

Smith v. Apple, 264 U. S. 275 .......................................... 50

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147 .................................. 36, 41

Southern Railway v. Greene, 216 U. S. 400 ...................42, 43

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513 .................................... 36

State ex rel. Knox v. Edward Hines Lumber Company,

150 Miss. 1, 115 So. 598 .................................................. 41

Stromberg v. Carlson, 283 U. S. 359 .............................. 34

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ................................ 35

Terral v. Burke Construction Co., 257 U. S. 529 ............. 43

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516.................................... 34, 36

Thomas v. State, 160 So. 2d 657 (1964) .......................... 50

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 86 .......................... 34, 37, 39

United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U. S. 144 .. 36

United States v. City of Jackson, 318 F. 2d 1 (5th Cir.

1963) .................................................................................6,33

United States v. Duke, 332 F. 2d 759, 765 (5th Cir.

1964)

PAGE

51

vu

United States v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. 353 (E. D.

La.) .... 51

United States v. Mississippi, 229 F. Supp. 925 (S. D.

Miss. 1964) ..................................................................... 34

United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961) ..49, 50

Wells Fargo & Co. v. Taylor, 254 U. S. 175................... 50

Western Union Telegraph Co. v. Kansas ex rel. Cole

man, 216 U. S. 1 ............................................................. 43

Williams v. Standard Oil Co., 278 U. S. 235 ................... 43

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 .............................. 36, 41

Othek A uthorities

89 U. Pa. L. Rev. 453, 454 (1941) .................................... 42

S tatutes

28 U. S. C. §1343(3) ............................................................ 19

28 U. S. C. §2283 ............................................................ 49, 50

42 U. S. C. §1983 ............................................................ 19, 49

Rule 43(c), F. R. C. P ........................................................26, 29

Fla. Stat. Ann. 542.01 et seq............................................. 41

Ga. Code Ann. Sec. 20-504 ................................................ 41

La. Rev. Stats. 51:121-126 ................................................ 41

Mississippi Business Corporation Act, P. B. #1712,

regular session 1962, Section 2-105.............................. 44

Sec. 1088, Mississippi Code of 1942, Ann.......................32, 41

Sec. 2056(7), Mississippi Code of 1942, Ann................... 31

PAGE

V l l l

Sec. 4065.3, Mississippi Code of 1942, Ann............. 31, 34, 51

Sec. 5310.1, Mississippi Code of 1942, Ann....... 44, 45, 46, 47

Sec. 5319, Mississippi Code of 1942, Ann....................... 44

Sec. 5339, Mississippi Code of 1942, Ann........................ 45

Sec. 5340, Mississippi Code of 1942, Ann........................ 45

Sec. 5341, Mississippi Code of 1942, Ann........................ 45

PAGE

I n th e

luttefc States dflurl of Appeals

F ob th e F ifth C ircuit

No. 21741

N ational A ssociation for the A dvancement of

Colored P eople, et al.,

Appellants,

—v s-

A llen T hom pson , M ayor of th e City of

J ackson , M ississippi, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

A. The Case in Summary

This appeal presents for review the decision of the dis

trict court for the Southern District of Mississippi denying

all relief sought by appellants who filed suit in June 1963

seeking injunctions against officials of the City of Jackson

and the State of Mississippi, who had inter alia, failed to act

upon the corporate appellant’s request for registration re

quired by State law, and, through policies of arrest, harass

ment, and intimidation, suppressed virtually all public

protest against racial segregation and discrimination.

Appellants, seeking relief in forms that will maintain and

safeguard their constitutionally protected right to effec

tively express their opposition to Mississippi’s racial poli

cies, have compiled a lengthy documentation of precisely

what happens to proponents of racial equality in Missis

sippi’s racially-closed society, and have offered proof that

2

the governmental segregation policies which this Court has

judicially noticed in other situations, operate here to deny

fundamental rights of free speech and association, and re

dress in the State’s courts for such deprivations.

B. Racial Climate in Jackson

As of Spring 1963, Jackson, Mississippi was a racially

segregated city. The Negro communuity had long endured

the inequities of enforced segregation, discrimination, po

lice brutality and the denial of the right to vote (R. 503-04).

There was increased frustration over the inability even to

express their discontent about racial segregation (R. 748-

778). Earlier efforts to desegregate the public library

(P.R. 1164),1 the City Zoo (P.R. 547-49, 599), the City

buses (P.R. 660), the Greyhound bus terminal (R. 863-65),

and the public swimming pools (R. 691) had resulted in

harassment and arrests.

Jackson’s Mayor, Allen Thompson, readily admitted he

knew of no hotel, tavern, motel, or restaurant in the City

of Jackson accommodating both whites and Negroes (R.

266-67). Negroes who had spent their lives in Jackson

had never been allowed to use the restroom facilities on

or around Capitol Street (Jackson’s main shopping area)

(R. 48), nor were they able to obtain jobs other than as

maids or busboys (R. 481). Indeed, Negro citizens of Jack-

son were surrounded by “ discrimination in all phases of

everyday life” (R. 509), and were denied basic human dig

nity in all business, official or social transactions; they were

not addressed as Mr., Mrs., Miss, but rather “boy” , “ uncle”,

or by their first names (R. 509).

The prevailing racial policies and customs not only op

pressed Negroes against whom they were directed, they

also effectively stifled any incipient dissent within the white

community. White citizens at odds with the orthodox view

accommodated either by choosing occupations which mini

mized social pressures for conformity or by leaving Mis

sissippi altogether (P.R. 1277). Departure from the racial

1 P.R.— refers to statements based upon proffered testimony or

exhibits which the trial court excluded.

3

norm is undertaken only with considerable social, occu

pational and even physical risk (P.R. 1313-14).2

In Jackson, the orthodox view on race is consistently pre

scribed in editorials and columns (R. 1210-11) in the two

major Jackson papers—the Jackson Daily News and the

Clarion-Ledger (P.R. 1208). The Negro position is never

published (R. 522, 1208), even though protest meetings are

regularly covered by white reporters (R. 541-42, 1404).

Moreover, there is only limited access to radio and TV

by Negroes or those who wish to speak on their behalf (R.

956).3

C. Appellants’ Self-Help Efforts

1. Bi-racial Committee Proposal

The civil rights proponents, including appellants, did

not initially attempt to convey their views by public pro

tests. The Jackson NAACP approached the Mayor on a

conciliatory basis by a letter expressing its desire “ to meet

with city officials and community leaders to make good faith

attempts to settle grievances and assure full citizenship

rights for all Americans” (R. 204). The Mayor did not

reply. Subsequently, a telegram from Medgar Evers re

quested formation of a “ representative bi-racial committee

to begin negotiations as in other progressive cities” (R.

206). The Mayor explained that any response would have

been contrary to policy in dealing with the racial situation

(R. 215). These requests, together with events occurring in

other cities, convinced him that “ they were going to force

people to do as they wanted to do whether it was legal or

whether it was illegal” (R. 202-3). He elaborated further at

the trial:

2 As a result of the selective patronage campaign, one or two

of the stores on Capitol Street indicated willingness to serve Ne

groes on a non-segregated basis but hesitated for fear of community

reprisals (R. 460).

3 A small four page weekly newspaper supports their position,

but it is not distributed in any substantial numbers to the white

community (R. 523), while a larger weekly newspaper, seemingly

aimed at the Negro community, has long been discredited as sup

ported by and reflecting the views of segregation groups (R.

1650-51).

4

The NAACP insisted that the commissioners and I

appoint a bi-racial committee, and they would have

taken over the whole city, this would only have been

the first of their demands . . . in any bi-racial com

mittee that I have ever seen, the radical element takes

over and assumes all the authority (R. 1730).

Those who negotiated with the Mayor over the formation

of the committee had also approached local businessmen

over the proposal. The businessmen indicated that there

was an “ agreement” among the various organizations to

let the Mayor and the Commissioners handle it (R. 516-17).

2. Mass Meetings

In need of a forum for expression of their sentiments,

frequent mass meetings are held to encourage the Negro

community to support a drive for desegregation (R. 50).

Members of the press are present at meetings (R. 1404,

1433), and there are always some white spectators (R. 1432-

33). A plainclothes Jackson police officer attended many

meetings and was recognized by appellants (R. 1453-54).

The main topic at the mass meetings is racial segregation

and how it can be eradicated (R. 1467). Civil rights ad

vocates speak at these meetings, and generally encourage

persons attending to register to vote (R. 1467-68), support

selective buying campaigns, and take other action to secure

racial equality. Although the speeches are quite militant

and on occasion contain spirited language (R. 1409), speak

ers at these well attended meetings (R. 1411, 1415, 1416,

1456) condemn violence as a method for attainment of

goals. Continually emphasized is that the battle is a non

violent one.

At the meetings, the unsuccessful efforts to negotiate

racial problems were reported (R. 1411), and, after votes of

approval by the audience, plans were made for various

peaceful demonstrations in opposition to racial segregation.

Volunteer participants in protest activities were instructed

in non-violent methods of protest (R. 380-85; 1030; 1059;

1153-54).

5

3. Selective Buying Campaign

A selective buying campaign (sometimes referred to as a

“ boycott” ) designed to bring the Negroes’ grievances to

the attention of Jackson merchants (R. 490) was begun as

another effort to confront the City with its racial practices.

Negroes were asked not to patronize businesses where

they were not hired or where they were treated differently

from white patrons (R. 429). Voluntary support for a

campaign was solicited by telephone and door-to-door can

vassing (R. 429-30).4

The purpose of the campaign was to secure equal treat

ment for Negroes, not to put anyone out of business (R.

431). When reports were received that a store was pre

pared to treat Negroes equally and to up-grade them in

jobs, selective buying was terminated at that store and the

people previously engaged in selective buying were advised

of the changed policy through mass meetings and leaflets

(R. 460).

Efforts were made to picket the Capitol Street business

area, urging shoppers to withhold patronage from stores

having policies of racial discrimination, but pickets were

promptly arrested. An interracial group of six college

students attempting to picket a Woolworth’s store on Capi

tol Street early one morning in December 1962 by walking

close to the curb, was immediately arrested by 20 to 30 city

policemen and charged with parading without a permit and

obstructing the sidewalk although there were no pedes

trians, and police and store personnel were the only wit

nesses to their activities (R. 954-56; 858-63).

4 In an open letter pledging continuation of the campaign with

more handbills and picketing, Jackson’s businessmen were advised:

“ This is not a fight of race against race— but let us tell you that

it is a fight between humanitarian democracy on the one hand and,

on the other, a strangling racism which even many of you must

sometimes wish were gone entirely from the Mississippi scene’

(D ’s Exh. 10, R. 1126).

While critical of appellants’ selective buying campaign, Mayor

Thompson called publicly for a “boycott” of a nationally-known

television program after its stars cancelled a scheduled appear

ance in Jackson because of the City’s segregation policies (P i’s

Exh. 28, R. 1737-38).

6

Roy Wilkins, NAACP Executive Secretary, Medgar

Evers, and a Negro woman were arrested while attempting

to picket on Capitol Street and charged with violation of

the State’s restraint of trade statute, a felony (R. 1353).

4. Voter Registration Attempts

Large numbers of Negroes attempted to register to vote

during the summer of 1963. At the height of the registra

tion campaign, the registrar’s office closed, allegedly be

cause of a dearth of help (P.R. 424). Offers by Negroes to

provide the necessary secretarial assistance were rejected

(P.R. 427). A Negro girl canvassing houses with voter

registration material was quickly arrested (R. 880-81).

D. Public Protests

Toward the end of May, 1963, it appeared that efforts by

civil rights groups to obtain any serious consideration of

their problems by Jackson’s city officials was doomed to

failure (R. 510-17). Moreover, despite two years of inten

sive litigation,5 all public facilities were maintained on a

completely segregated basis, the selective buying campaign,

with few exceptions, had failed to achieve its goals (R.

460), and perhaps most frustrating of all, appellee Mayor

Allen Thompson had not only flatly rejected pleas for a

bi-racial committee (Pi’s Exh. 27(7), R. 516, 1729), but

continued broad publication of the view that “ separation

of the races in Jackson has been extremely successful. The

people believe in it” (P i’s Exh. 27(6), R. 1715). Appellants

determined that they must inform the public that Jackson

Negroes were dissatisfied with the maintenance of segrega

tion (R. 802,1113-14,1129-30).

5 Bailey v. Patterson, 199 F. Supp. 595 (S. D. Miss. 1961), 368

U. S. 346, 369 U. S. 1 (1962), 323 F. 2d 201 (5th Cir. 1963),

effort to end segregation in travel facilities in the State and

City of Jackson; United States v. City of Jackson, 206 F. Supp. 45

(S. D. Miss. 1962), 318 F. 2d 1 (5th Cir. 1963), suit to end

segregation policies in Jackson waiting rooms of common carriers;

Clark v. Thompson, 206 F. Supp. 539 (S. D. Miss. 1962), 313

F. 2d 637 (5th Cir. 1963), action to end segregation in Jackson’s

recreational facilities and libraries.

7

1. Picketing

Appellants’ concentrated public protests began on May

28, 1963, when an interracial group of seven or eight per

sons sought to picket Capitol Street (R. 657) with signs

reflecting their goals and determination: “We want equal

ity,” “We shall overcome” (R. 686). They were 10 spaces

apart and walked close to the curb (R. 658), but were ar

rested before they could cover even one block and the signs

were torn from around their necks (R. 686-87).

During each of the next few days, small groups picketing

in similar fashion were quickly arrested when they appeared

on Capitol Street at the “ Parisian” Store (R. 657-58), the

Woolworth Store (R. 480-83), H. L. Green’s (R. 658-59),

J. C. Penney’s (R. 743-44; 649-50), and Walgreen’s Drug

Store (R. 658-60, 671-73).

Efforts to vary the traditional picketing procedure in

hope of avoiding arrest proved of no avail. On June 7,1963,

five Negro parents walked single file, three or four feet

apart from the sidewalk to the City Hall steps and stood

silently where they did not block the steps (R. 630-31).

Deputy Chief of Police, Captain Ray, approached them and

asked if they wanted to see somebody in City Hall. They

did not reply “ because the signs that we were carrying told

what we were asking for and I was carrying an American

flag and the other mothers was carrying placards” (R. 631)

which read “We Want Equality.” While their heads were

bowed in silent prayer, Captain Ray asked them to move on.

When they did not move, he arrested them (R. 632-33).

On the same day, five persons, each with a small American

flag started up Capitol Street. They walked single file,

three feet apart, and well over toward the curbside of the

sidewalk, but were arrested within ten minutes for parading

without a permit (R. 726). A week later, the same charge

was placed against an eighteen year old Negro youth who

appeared alone on Capitol Street wearing a tee-shirt reflect

ing “ NAACP” (R. 940-41), and six months later in De

cember 1963, six Negro housewives attempting to picket on

Capitol Street without placards but with small American

flags and wearing pullover shirts with printed slogans:

8

“Remember Evers” , “Remember Kennedy” , “ I Want Free

dom” were quickly arrested and charged with obstructing

the sidewalk and parading without a permit (R. 759-60),

although they walked fifteen feet apart, three on each side

of the street (R. 758-62).

A group of teenagers who sought to picket the City

Jail in protest against the arrest of one of their leaders for

contributing to the delinquency of minors were themselves

arrested (R. 899), but ten Negro boys wearing NAACP

tee-shirts with Freedom signs printed on the backs were

able to remain on Capitol Street for 30 to 45 minutes with

out arrest. Their technique was to stay from 20 to 30 yards

apart on both sides of the street, and not march but stroll

up and down as if they were window shopping (R. 772-74).

Passersby stared but otherwise ignored the boys, but one

of the many police in the area gave one of them a ticket for

jay-walking (R. 774-75).

2. Testing Public Accommodations

On May 28,1963 a group of college students made various

purchases at Woolworth’s on Capitol Street and then

sought food service at the lunch counter (R. 1005, 1016).

They were refused service and surrounded by a mob of

several hundred white persons (R. 1196) who splattered

them with water, vinegar, salt, pepper, mustard, and catsup

(R. 1196, 1632). One observer, the President of Tougaloo

College, recounted:

It was a mob—it wasn’t just 200 people, it was a genu

ine mob and they were shrieking whenever somebody

would make a hit . . . hit with some mustard or catsup

or something of the kind” (R. 1196).

For a long while the Chief of Police and 20-25 policemen

remained outside the store allegedly waiting for an invita

tion from the store management to quell the disturbance

(R. 1015, 1198, 1606), although they had a clear view from

the street to the lunch counter (R. 1017) and were advised

by several persons, including a plainclothes detective, sta

tioned at the counter, that the crowd was unruly and dan

gerous (R. 1196).

9

One of the students, Memphis Norman, was attacked

from behind while sitting at the counter and badly beaten

(R. 1007, 1011). Trained in non-violence (R. 1030) he of

fered no resistance, but was arrested for breach of the

peace together with his attacker who was charged with

assault (R. 1997).6

The following day at Primos Restaurant on Capitol

Street, five Negroes were arrested when they attempted to

sit down and eat at the counter (R. 799). They were stopped

at the door by the owner (R. 799) and subsequently arrested

for trespass by Deputy Police Chief Ray, one of the many

police officers in the area (R. 804, 823).

On July 19th, three Negro youths sought to use the

facilities at the Jackson Y.M.C.A. designated for whites and

were asked to leave the building (R. 1038, 1041-42). They

left but sat on the front steps in protest and, although not

blocking the entrance, were arrested by Jackson police

when they refused to leave (R. 1042-43).

Later in the year, Negroes and interracial groups sought

to worship at white churches in Jackson (P.R. 866, 959,

994-95). These groups were generally arrested even when

a member of the church was in the group (P.R. 992, 994-95).

3. Public Meetings

On May 30th, 13 or 14 persons (R. 689) met on the post

office steps in order to make a public statement opposing

segregation (R. 802). The participants believed that by

choosing a federal building as a place for their protest they

would avoid police harassment and arrest (R. 810-11). The

meeting was to begin with a prayer service (R. 1128) and

“ then one of our members was to make a statement appeal

ing to all people of Jackson for an end to police brutality

and for a bi-racial commission. The prayer service was a

part of it, but it was only a small part of what we were

doing—to make a public protest” (R. 1128).

When the group came out of the Post Office, a large num

ber (R. 688, 804) of policemen had assembled in the area,

6 At a hearing, the charges against Norman were dismissed

(R. 1012).

10

as well as an unruly crowd of white persons who had gath

ered and jeered and cursed the group while they prayed

(R. 747, 1128). The group was arrested shortly after the

prayer was begun and charged with breach of the peace (R.

803). None of the white persons were arrested (R. 716,

824).

Deputy Chief Ray testified that the “ugly mood” of the

white crowd (R. 1540) made him aware “ that there was an

immediate danger there and I felt it necessary to take some

action and to do it quickly to avoid a riot.” He explained

his failure to arrest any of the white mob:

I did not arrest them. After I determined the cause of

the trouble, I tried to remove that cause and after the

cause was removed, it was very peaceful again (R.

1590).

4. Protest Marches

None of several other mass meetings planned to be

held at City Hall took place because participants were in

variably arrested enroute, generally for parading without

a permit (R. 980, 1052). A parade permit had been re

quested prior to a scheduled march on May 30th from the

Farish Street Baptist Church to City Hall where a protest

to the Mayor was to be made (R. 575, 833, 1077). The per

mit was refused by city officials (R. 1054).7

A group of several hundred persons, some carrying flags

(R. 1057), left the Church and began marching two by two

toward City Hall. There were approximately 100 to 200

policemen in the area (R. 833) who had formed a “ skirmish

line” across the line of march from sidewalk to sidewalk

(R. 1508). Over a loudspeaker, Deputy Police Chief Ray

asked if they had a permit to parade, and then ordered them

to disperse (R. 1511). Three hundred and twenty-two were

7 Later, at a hearing on the injunction obtained by the City,

Mayor Thompson stated he would not grant a parade permit to

appellants (P i’s Exh. 29, p. 372).

11

arrested (R. 1512), and transported, some in garbage

trucks, to a detention center set up at the City fairgrounds

early in May, 1963 preparatory to incarcerating any per

sons who might participate in public protests (R. 1514-15).

On May 31, 1963, there was another mass arrest when

a group of 80-90 students from the Negro Brinkley High

School walked twro abreast (R. 904, 978-1057) on the side of

a road toward the Jackson City Hall, intending to make a

peaceful protest against racial segregation. The following

day, a group of approximately 100 persons (R. 585) headed

for downtown Jackson (R. 589) for a similar purpose. All

were arrested (R. 594).

Not all groups arrested enroute to meetings or public

protests were large. On June 12, 1963, the morning follow

ing announcement of the ambush murder of NAACP Field

Secretary Medgar Evers, a group of 12-15 Negro ministers

attempted to walk slowly in single file from the Negro

Pearl Street AME Church to the City Hall for “prayer and

consultation” with the Mayor about the tense racial situa

tion, and to urge the Mayor to halt racial violence and form

a biracial committee (R. 1106). They were met by police

almost immediately, arrested and taken to the city jail

(R. 1107).

Later that same day, a group of 130 students, distressed

over the death of Evers (R. 560; 601) and the arrest of the

ministers (R. 1107) acquired small American flags and at

tempted to proceed to downtown Jackson (R. 589) on public

streets located in the Negro section of Jackson (R. 1659).

After walking a half-block (R. 553) they were stopped by

approximately 100 policemen (R. 1109) who were lined up

across Lynch Street, stopping traffic (R. 844).

Appellant Rev. King, who observed the incident, recalled:

I saw clubs going in the air. I could see people being

struck by the police. . . . You could see clubs swinging

and then suddenly the American Flag would fall (R.

1111; 1060).

He described the show of force by the police in the Negro

area after the demonstrators had been arrested and taken

away:

12

They moved down the street again, clearing the street,

people running before them, with cadence count, march

ing. Police would come to a porch where people would

be singing freedom songs, they would aim their guns

at the porch and orders would be given for people

to stop singing on the porch. . . . (R. 1112).

One hundred and fifty-six persons were arrested, includ

ing 74 juveniles (R. 1658) and charged with parading

without a permit. One demonstrator testified that she did

not recall that there was a request to disperse because:

“ When they stopped us he was telling the policemen to load

them up, bring the paddy wagons and bring the garbage

trucks” (R. 704).

On June 13, a group of approximately 80 persons who

left the Pearl Street Church (R. 895) two by two carrying

American flags (R. 895) were arrested and charged with

parading without a permit before proceeding more than a

block and a half (R. 896). On June 15, the police granted

permission for a procession to follow the funeral ceremonies

for Medgar Evers. The procession was guarded by police

and proceeded approximately 1% miles through the city

streets to a funeral home in a Negro section. As part of

the large group of participants attempted to leave the area,

they found the area blocked by police. Participants in the

funeral procession reported that onlookers in the buildings

and on the sidewalks along the street who had not been

part of the procession, threw bricks and bottles at the police

(R. 1158), but Deputy Police Chief Ray testified that it was

the processional participants who rioted and attacked his

men (R. 1536-37). Chief Ray admitted, however, that he had

left the area when the funeral procession reached the fu

neral home and returned when advised there was trouble.

He also admitted he did not know of his personal knowledge

who or how the rioting started (R. 1558).8

Appellant Rev. King testified that the procession was

orderly until police turned on a group with dogs and guns

and chased them down the street (R. 1158).

8 The description of this event which appears in the opinion of

the court below (R. 146-47) does not conform with any part of

the Record.

13

“ Q. Are you telling the Court that the people in

volved in the throwing of bricks and bottles on Farisli

Street were not parties participating in the march for

Medgar Evers’ funeral? A. I think that’s a very, very

apt description. The people who throw bottles and

bricks were not people involved in the march for the

funeral. The march had been conducted just as we

planned it, just as peacefully as we had planned it.

You had given us permission to do it. I think we

marched the five thousand people peacefully and could

have done so on any occasion that the police in Jackson

were willing to give us protection to do so” (R. 1158-59).

5. Public Parks and Libraries

Efforts were made by Negroes to use the city parks and

libraries on a nonsegregated basis. Jackson police reacted

to these efforts by harassing or arresting the participants.9

When on June 7, 1963, 21 young people attempted to use

the facilities of the traditionally white Battlefield Public

Park, they were ordered to leave (R. 827-28), followed by

police, and finally arrested for blocking the street (R. 829-

30, 1532). Deputy Chief Ray who effected the arrests, re

ported that he ordered the Negroes out of the Park because

he anticipated trouble from a group of whites who arrived

in cars and were advancing on the Negroes (R. 1882). This

white group was neither followed nor arrested (R. 1584).

A few weeks later, a large group of Negroes attempted to

use the facilities in Riverside Park. They refused to leave

on orders of a policeman, and were arrested (R. 723; 830).

Negroes seeking to use Jackson’s main library in 1963,

were not arrested as had been the case in 1961 (P.R. 1164-

65), but they were harassed by policemen who followed

them around and stood near their seats (R. 864; P.R. 1033).

9 In 1962 a suit had been filed in federal court to desegregate

Jackson’s parks and libraries. The decision by the district judge,

affirmed on appeal, declared that the plaintiffs were entitled to

use the facilities hut refused injunctive relief for plaintiffs and

the class they sought to represent. Clark v. Thompson, 206 F.

Supp. 539 (S. D. Miss. 1962), aff’d 313 F. 2d 637 (5th Cir. 1963).

14

E. Jackson’s Response

Public protests were viewed as an effort to take over

the City (Pi’s Exh. 27(10), R. 1732-33) and preparations

were made to meet this threat through a policy of “ instant

arrest” of all civil rights proponents (R. 231-32).

1. Preparations for Arrests

In late Spring 1963, the Mayor consulted with the police

chief over arrangements to augment the capacity of the

jail (R. 192), and before any demonstrations had occurred,

facilities were made available at the fairgrounds to hold

in custody large numbers of people (R. 209).

The Mayor instructed the Jackson Police Force to arrest

persons engaged in unlawful conduct. He did not define

“ unlawful conduct” (R. 228).

2. Arrests and Prosecutions

Approximately 1,000 persons were arrested (R. 1351),

50% of whom were juveniles (R. 1347), and variously

charged with parading without a permit, obstructing the

sidewalk, trespass and breach of the peace (R. 1352). From

May 31st through July, 1963, the juvenile court handled

665 children. Fifteen youths who had participated in two

or more demonstrations were referred back to the Police

Court (R. 1676). Juveniles arrested between May 13 and

June 1st were released to parents on the condition that they

not demonstrate again (R. 1677). Those arrested after

June 1st were brought to court. Cases of those for whom

it was a first offense are being held open without adjudica

tion for one year (R. 1679) which Youth Court Judge

Gurnsey admitted has the effect of barring their participa

tion in other civil rights protests during that period (R.

1684).

Appellant’s attorney Jack Young, one of only three Mis

sissippi lawyers willing to take civil rights cases (R. 1743)10

described what happened to persons arrested while pro

10 The other two attorneys R. Jess Brown and Carsie Hall are

Negroes as is Jack Young (R. 1332, 1754).

15

testing segregation. His testimony may be summarized as

follows:

Bail Bonds—Bonds for those arrested, and charged with

violation of a City Ordinance such as parading without a

permit were $100. Appeal bonds from the City to the

County Court were an additional $225 (R. 1352). Where

defendants were charged with violating State statutes, i.e.,

breach of peace or obstructing sidewalks, bail bonds were

$500, except that $1,000 bail was set for persons charged

with violating the State’s restraint of trade statute (R.

1352-53).

Defendants were required to post cash bonds, because few

persons were able or willing to post property bonds and

local bonding companies refused to furnish either appear

ance or appeal bonds (R. 1333).11 As of February 1964,

$89,900 in cash bonds had been posted for appeals from the

City to the County Court and $67,500 in appeal bonds from

the County to the Circuit Court (R. 1334-35). Bonds for

cases appealed to the Circuit Court are $1,500 each (R.

1352).

Trials—Despite the great factual similarity of cases, all

civil rights prosecutions are conducted separately. Re

quests to consolidate the “ Freedom Rider” cases for trial

were refused by the City Prosecutor, and both Circuit and

Supreme Courts of Mississippi have denied motions to con

solidate cases on appeal (R. 1336-37). Attorney Young tes

tified that all 45 persons tried in County Court as of the

trial date (R. 1355) had been convicted, except for a few

acquittals on motions for directed verdicts (R. 1341-42,

1346).

The maximum penalty is uniformly imposed after con

viction. For City Ordinance cases this is $100 fine and 30

11 Attorney Young testified that while representing the “ Freedom

Riders” in 1961, local surety companies refused to provide bonds.

He then wrote to every casualty company in the State (over 300)

asking if they would write surety bonds in civil rights cases.

He failed to receive a single affirmative reply (R. 1340-41). Appeal

bonds totaling $194,000 have been posted in the Freedom Ride

cases (R. 1334).

days jail sentence (R. 1355). State violations are $500 fine

and four months imprisonment (R. 1355-56). Nolo conten

dere pleas have been entered for many defendants who,

for varying reasons, did not appear for trial de novo in

County Court (R. 1745-46).12

3. Harassment

In addition to arresting and prosecuting persons involved

in civil rights protests, Jackson police were charged with

beating demonstrators (R. 578, 636; 1054-55; 553, 602, 701),

or allowing them to be beaten by white mobs (R. 1015, 1198,

1606).13 Participants in the larger protests were trans

ported to the detention center at the Fairgrounds in city

garbage trucks (R. 1514-15). These trucks, appellants’ wit

nesses charged, were dirty, hot, had dirty water in them and

contained no windows and a single door (R. 576). They

contained a vacuum mechanism used to compress the gar

bage, and were clearly intended to move materials, not

people (R. 1574-75). The drivers of these trucks took long

routes to the fairgrounds, stopping and starting abruptly,

causing those inside to fall (R. 577, 718). Those trans-

portees to the fairgrounds were frequently kept in the

closed paddy wagons or garbage trucks for 35 to 40 min

utes in 90 degree heat (R. 719). Charges of inhumane

treatment were generally denied by city officials and police

(R. 1515, 1658). Indeed, testimony was offered by appel

lees attempting to show that all arrests were justified by

the conduct or activities of those taken into custody (R.

1610, 1682-83).

12 The Record indicates that while civil rights demonstrators

were arrested because their protest activity caused white persons

opposed to their views to become violent (R. 1540, 1590; 1589,

1882), only one of these persons, Benny Oliver, an ex-policeman,

was arrested and prosecuted for assaulting a demonstrator (R.

1008).

13 A parade participant during her trial for parading without

a permit testified that she had seen Jackson police officers strike

other persons involved in the march. When police officers denied

this, Judge Moore (R. 1360) had her bound over to await grand

jury action. She was indicted for perjury (R. 1354-55).

17

4. State Court Injunction

On June 6, 1963, the City requested and obtained, ex

parte, a temporary injunction against the NAACP and

various other groups and individuals engaged in civil rights

activities (Pis. Exh. 29). The injunction, issued by the

Hinds County Chancery Court, ordered those named to

cease inter alia street parades, blocking of public streets

and sidewalks, trespassing on private property, all of which

conduct was characterized as unlawful and illegal (R. IS

IS).14

F. Denial of NAACP Registration

For a number of years, corporate appellant, National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP) has been active in Mississippi (R. 476). It

sponsors several branches throughout the State and main

tains a Field Secretary’s office in Jackson.

The NAACP, organized to use lawful means to end

racial discrimination in all aspects of American life (R.

394, 419), is a non-profit membership corporation char

tered under the laws of New York, with local affiliates in

more than a thousand communities in 49 States (R. 394).

In Mississippi, NAACP works to achieve equal rights for

Negroes, by litigation of unjust laws, encouraging regis

tration and voting, desegregating public facilities includ

ing schools and ending police brutality (R. 420-21). In

this effort, NAACP has worked with other groups who

share its views (R. 436, 493, 506-07), has participated with

them in selective buying campaigns (R. 445), and in picket

ing and other public protest activities (R. 421).

Pursuant to a 1962 notice from the Secretary of State

that laws with regard to foreign non-profit corporations

had been changed by amendment of Section 5319, Missis

sippi Code of 1942, Ann., and that, effective January 1,1963,

such corporations would be required to “domesticate” by

14 After trial in January, 1964, the temporary injunction was

made permanent on May 20, 1964, and appeal therefrom is now

pending before the State Supreme Court.

18

the filing of an application and a certified designation of a

local agent for service of process, on November 27, 1962,

appellant corporation filed a certified copy of a resolution

designating its Mississippi agent, with appended accept

ance by the agent, together with an authenticated copy of

its articles of incorporation, requisite filing fees, and a

request that their organization be domesticated.

Prior to commencement of this action appellees had

neither acted upon the application nor advised appellants

of its disposition. After this action was filed, appellees

produced a letter from former Governor Barnett (in whose

stead the present Governor has been substituted) dated

June 17, 1963, denying that application, pursuant to the

authority vested in him as Governor; and a letter dated

June 19, 1963, from appellee Ladner to the President of

appellant corporation advising it of the Governor’s refusal

to approve its application for domestication. During a

hearing on appellant’s request for temporary injunctive

relief, on June 24, 1963, appellee Attorney General Patter

son, produced a letter to Governor Barnett dated January

29, 1963, setting forth the Attorney General’s opinion that

the application for domestication by appellant corporation

“ is not authorized to be approved by your office” (R. 327);

he testified that his opinion was based upon appellant cor

poration’s failure to comply with Section 5310 of the Mis

sissippi Code of 1942 as a prerequisite to domestication

and his belief that domestication of appellant corporation

would not be “ in the best interest” of the State of Missis

sippi. Finally, on July 11, 1963, the President of appellant

corporation was formally advised that the Governor had

declined to approve the application for domestication in

the State of Mississippi.

The record reflects that the conclusion of the Attorney

General that domestication of the NAACP was not “ in the

best interest of Mississippi” is based upon his experience

with the NAACP. According to him, during the period it

operated in the State, it encouraged and conducted activ

ities to acquire civil rights for Negroes and to protest

denial of civil rights to Negroes, including protest proces

19

sions and meetings, and promoted and “ stirred up” litiga

tion dealing with civil rights which, in the opinion of the

Attorney General, was uncalled for (R. 340; 344).

G. Summary of the Litigation

1. Suit Is Filed

The two-count Complaint filed June 7, 1963, invoking the

jurisdiction of the federal court under 28 U. S. C. §1343(3)

and seeking relief as authorized in 42 U. S. C. §1983 (R. 3),

alleged that more than 600 persons were arrested since

May 27th (R. 10), and except for juveniles, most had been

found guilty, given maximum sentences, required to post

bonds from $100 to $1,000, and required to take separate

appeals entailing such huge expenditures for court costs,

bail and appeal bonds that many persons will be deprived

“ . . . of any possibility of preserving and protecting through

the judicial process their [constitutional] rights. . . . ” (R.

10-11).

Appellees in Count I,18 were charged with acting under

color of state laws and customs now and for many years

“ to effectuate and maintain throughout the City of Jackson

the most rigorous and virulent form of racial segregation

now existing in the United States” (R. 5). The complaint

charges that appellees, acting in compliance with explicit

state constitutional provisions and statutes (R. 5-6), twist

and distort state laws and city ordinances to harass and

punish persons objecting to their racial policies, and “ abuse

and subvert the judicial processes of the courts of the State

to the same end” (R. 6).

Appellants alleged their sole aim is to exercise rights of

peaceful assembly, freedom of speech, and petition for re

dress of grievances and appellees know that all such activity

is constitutionally protected (R. 9). Thus, arrests for

breach of peach, restraint of trade, trespass, parading

without a permit and obstructing traffic are made “ solely 15

15 The Majmr, City Commissioners, Chief and Deputy Chiefs of

Police, Prosecuting Attorneys of the City of Jackson, the Sheriff

and County Attorney for Hinds County and the Commissioner of

the State Highway Patrol (R. 4-5).

20

for the purpose of harassing and intimidating” appellants

even though appellees know that under all these circum

stances, valid convictions cannot be obtained (R. 10).

Because appellants intend to continue their protests

against appellees’ racial policies, and appellees intend to

continue denying their right to peacefully and lawfully en

gage in activity designed to eliminate racial discrimina

tion, appellants alleged that they have “no adequate remedy

at law in the courts of the State of Mississippi. . . . ” (R.

12) .

Appellants sought injunctive and declaratory relief which

would: (1) declare the rights and legal relations of the

parties, (2) enjoin appellees’ policies of arrest and harass

ment which prevent appellants from peacefully and pub

licly protesting racial segregation through activities pro

tected by the Fourteenth Amendment, and (3) enjoin

prosecution of persons arrested but not tried or convicted

for participation in peaceful protests (R. 12-14). Follow

ing the trial, the prayer was amended to enjoin all prosecu

tions until the constitutional rights of such persons “ shall

first be declared by the Federal Courts in this or other

appropriate proceedings for relief. . . . ” (R. 133).

Count two adopts all the allegations of count one and

further alleges that the Governor, Attorney General and

Secretary of State of Mississippi have failed to communi

cate with appellant NAACP concerning its application for

registration as a foreign corporation qualified to do busi

ness despite compliance by the NAACP with all legal pre

requisites for so qualifying (R. 15-16). NAACP objectives

to eliminate racial segregation and discrimination are de

scribed as is its organization in Mississippi (R. 17). Appel

lees’ efforts to disenfranchise Mississippi Negroes and to

deprive them of constitutional rights are set forth, and

appellants review their peaceful and lawful efforts to se

cure the elimination of racial discrimination (R. 18-19).

Injunctive relief was sought to: (1) require appellees to

register NAACP as duly qualified to do business in Missis

sippi, (2) bar further court action aimed at hindering

NAACP or its members from pursuing their lawful objec

tives in the State, (3) halt further prosecution of both

21

NAACP officers for restraint of trade, and of the injunction

against NAACP and others obtained in a state court with

out hearing or notice on June 6, 1963 (R. 20-21).

2. Preliminary Injunction Is Denied

Appellants’ effort to obtain a temporary restraining

order and preliminary injunction, motion for which was

filed with the Complaint (R. 23-26), was frustrated by the

district court’s order of June 11,1963, taking the case under

advisement for later decision18 (R. 57-59).

3. First Appeal

Appellants appealed from this order (R. 59), and sought

injunctive relief from this Court pending appeal. On July

24, 1963, the appeal was dismissed for lack of jurisdiction,

this Court concluding that the order was not appealable,

and that the trial court had not abused its discretion16 17 18 19

(R. 62).

Upon remand, the trial court overruled appellants’ mo

tion for a further hearing (R. 91-95), and denied appel

lants’ request for a preliminary injunction (R. 129) as to

both Counts I 18 and II.19 Answers filed by appellees gen

16 The trial court, reviewing affidavits and briefs from both sides

and limited testimony received on June 8th (It. 170-285), post

poned decision because it viewed the case as extremely complicated,

and there is no crisis requiring immediate action since appellants

control their course of action. The court added its opinion that the

state court injunction obtained by appellees (R. 43-45) was not

void (R. 58-59). The injunction is still in effect.

17 See related case: In the Matter of Application of Brown &

Richards v. Ray field, 8 Race Rel. Law Rep. 425 (1963).

18 Chief Judge Cox found the proof did not show by a pre

ponderance of the evidence that appellants had any right to, or

need for, an injunction (R. 122-123); that their claim to an

injunction is “ full of doubt in this case” ; and that the presump

tion is that the arrests were proper in each instance and bore no

relation whatsoever to a policy of segregation (R. 124).

19 The preliminary injunction sought in Count II of the Com

plaint was denied by Judge Mize following a hearing (R. 318-69),

concluding that no emergency exists and a “matter of this impor

tance should be determined after a full hearing upon the merits”

(R. 126-27).

22

erally denied the pertinent allegations of the Complaint

(R. 76-90). Appellees in Count II pleaded affirmatively

that the action was barred by the Eleventh Amendment and

that “ the State of Mississippi has a right to exclude

foreign corporations from operating within its bound

aries, . . . ” (R. 81-82).

4. The Trial

Trial was held during five days in February 1964, dur

ing which appellants offered 50 witnesses and 29 exhibits

to support the contentions in their pleadings.

Mayor Thompson, called to identify his published state

ments critical of civil rights protests against the mainte

nance of a segregated society in Jackson (R. 1280-82) was

uncertain as to the accuracy of the statements claiming the

quotes were taken out of context (R. 1282-90). The trial

court admitted the statements as admissions (P i’s. Exh.

27, R. 1290) and subsequently Mayor Thompson (R. 1711-

43) reviewed them with explanations that generally ac

corded with the printed views:

“ The civil disobedience demonstrations of the past two

days were planned for the purpose of creating strife,”

—that is my belief—“ arousing passions and disrupting

business.”— This is my belief (R. 1722).

“ They can demonstrate, march, picket and riot from now

on, but they cannot win like this, it won’t get them more

money, more schools, or better jobs” (R. 1724).

“When Kennedy is out of office, and the NAACP has

milked innocent Negroes of their money and moved on,

local Negroes are going to have to look to the white

people who have helped them all the time” (R. 1725).

“ The Mayor labeled the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People the ‘NAACP which

covers all agitator groups to me. They are what all

intimidators represent to me.’ ” That is right (R. 1734-

35).

23

The court below opined that the Mayor’s opinions were

his own and did not reflect City policy because he does not

write ordinances alone but with the City Commissioners

(R. 1717); during his testimony in City of Jackson v. Salter,

Mayor Thompson evidenced an expressed intention to

officially carry out duties in resistance to recognition of

Negro rights:

“ Q. What is the policy of the City of Jackson with

respect to segregation of the races? A. I have said

that a thousand times in the last two or three years.

The policy is in certain instances, certainly. My belief

is that separation of the races is best for the white

and for colored. That I believe has been changed in

final Federal Court decisions, but as long as I ’m alive

I ’m going to be diligent in an effort to change them back

to what they were before people tried to influence per

son’s lives by laws and civil rights measures, and the

policy that we’ve adopted, I have set out very clearly,

the policy about a church the policy about a business”

(Pi’s. Exh. 29, pp. 453-54).

Commissioner D. L. Luckey advocates a similar racial

policy for the City. Proof of this was established through

appellants’ witness Rev. Harold Koons, pastor of the

Trinity Lutheran Church (R. 1198-99). Without permitting

appellants to explain the nature of Rev. Koons’s testimony,

the court sustained objection to it (R. 1200), necessitating a

proffer that during the summer of 1963, efforts were made

to have Negroes admitted to Rev. Koons’s church, that

some persons favored and others opposed this position and

during this period, Commissioner Luckey, a member of the

church, wrote a letter on City stationery addressed to

each member of the congregation stating that admission

of Negroes would create a disturbance, and if they sought

admission, they would be arrested and charged with breach

of the peace in accordance with the approach followed for

a numbers of years by the City of Jackson. The Com

missioner closed by appealing to members to save the

church by voting against mixing20 (R. 1201-02).

20 Appellants were also forced to proffer the fact that Rev.

Koons had resigned from the church because of the hostility on

24

5. The Excluded Proof

In addition to Rev. Ivoons’s testimony, the trial court ex

cluded large segments of appellants’ proof notwithstanding

counsel’s frequent and strenous arguments that the offered

testimony was relevant to the allegations and prayer for

relief set out in the Complaint.

Despite allegations that appellees for many years have

arrested all persons seeking to publicly protest racial seg

regation (R. 5), testimony regarding arrests of Negroes

who sought in 1961 to use the library (R. 1164), the zoo

(R. 547-49, 599) and city buses (R. 660) was excluded;

similar incidents occurring during the same year at an

interstate bus terminal (R. 971-73), a public swimming pool

(R. 691) and the Southern Governor’s Conference (R. 883-

85) were admitted.

Witnesses testified a major reason for public protests

was the inability of civil rights proponents to air their

views through usual news media which, themselves, favor

racial segregation (R. 522, 956-64). All such testimony

was uniformly excluded21 (R. 1207-11,1217,1244-46).

the part of the majority of the congregation toward his position

on the admission of Negroes to the church (R. 1203). On inquiry

from the court, Rev. Koons acknowledged that he had resigned

because of the difference of opinion with his congregation on the

racial question (R. 1203-04).

21 News stories, articles, editorials, and columns from the two

Jackson dailies, the Clarion-Ledger and the Daily News offered

as exhibits to appellants’ case uniformly supported continuance

of racial segregation and vehemently denounced those who espoused

the civil rights position (P i’s. Prof. Exlis. 7-27), i.e.,

The Clarion-Ledger strongly supported Governor Barnett in

his effort to bar James Meredith from the University of Mississippi

(P i’s. Prof. Exh. 24-1) and was highly critical of the United

States Government’s action at Oxford (P i’s. Prof. Exh. 24-3).

A U. S. Supreme Court decision protecting NAACP membership

lists in Florida was interpreted as a hindrance on efforts to curb

red subversion (P i’s. Prof. Exh. 24-5). Any departure from segre

gation, even the desire of a Mississippi state university basketball

team to play against an integrated team outside the state was

viewed with alarm (P i’s. Prof. Exh. 24-2), and an editorial proudly

affirmed: “ Mississippi is ‘still the last great citadel of segregation

in this country,’ and you can make a note of this further truth:

Mississippians are determined that it shall remain so” (P i’s. Exh.

25

Dr. Gordon Henderson, associate professor of political

science and Chairman of the Department of Political Sci

ence at Millsaps College in Jackson (R. 1317) sought to

testify that for a number of years he had made a study

of Jackson newspapers in connection with his work (R.

1318, 1321-22), that the news clippings offered by appel

lants (Pi’s. Prof. Exhs. 7, 8, 24) were “ typical” and “ repre

sentative” of racial views published in Jackson papers

(R. 1319-20), and that a contrary or critical view appears

only infrequently, and is never written by local columnists

(R. 1323).

Appellants submitted testimony in support of the Com

plaint’s allegations that the practice and policy of sup

pressing all objection to racial segregation was required

by State laws and customs and supported by the community

to the extent that appellees are able to “ . . . abuse and

subvert the judicial processes of the courts of the State”

(R. 6), thereby depriving appellants of “any possibility of

Prof. 24-6). A columnist analogized the Federal Government’s

action at Oxford to Russia’s suppression of Hungary’s freedom

fighters (P i’s. Prof. Exh. 18-2). James Meredith was referred

to as a “ Negro pawn of the NAACP” (P i’s. Exh. 19-3), and

reports of shotgun blasts into his family’s home were interpreted

as a “ convenient and effective gimmick for NAACP fund raisers”

(P i’s. Prof. Exh. 18-3).

The Daily News expounds that to follow the advice of “ leftwing

social reformers” and adopt as public policy, edicts contained in

various “race-mixing decisions” is a “blueprint for self-destruc

tion” (P i’s. Prof. Exh. 7-2); that Washington, D. C. is doomed

as a decent city because of integration (P i’s. Prof. Exh. 7 -3);

and that “ shocking evidence has been produced that Communists,

Commie-fronters, and their stooges are active in the South in

efforts to create friction and violence between the races” (P i’s. Prof.

Exh. 7-11). When A. D. Beittel, President of Tougaloo College

wrote a letter to the Editor critical of published statement by

appellee City Commissioner Tom Marshall that the Negroes of

Mississippi are satisfied, the News published the letter and added

a comment that Marshall spoke for the majority of Negroes, and

Beittel for “ those chronically disgruntled clusters of agitators

who are not satisfied” and never can be satisfied (P i’s. Prof. Exh.

7-5). While decrying the violence in NAACP field secretary

Medgar Evers’ death, the News stated “ visiting agitators here in

the past two weeks had set the stage for potential violence” (P i’s.

Prof. Exh. 7-12).

26

preserving and protecting their constitutional rights

through the state judicial process” (R. 11). They offered

the 1963 Report of the Mississippi Advisory Committee to

the United States Commission on Civil Rights (Pi’s. Prof.

Exh. 5), and called the Committee Chairman who testified:

“ The Committee was convinced after hearing the testimony

of many witnesses that it was substantially impossible for

Negroes to receive equal treatment before the law at the

present time” (R. 1174). Objection to the testimony and

Report were sustained22 (R. 1175, 1177), as were all simi

lar objections (R. 1324).

In support of appellants’ requests for broad relief, in

cluding enjoining prosecutions, evidence of the commit

ment of state officials and agencies, community leaders,

politicians and the community to racial segregation, was

excluded notwithstanding counsel’s efforts to explain its

admissibility (R. 661-62, 988-89, 1040).

The excluded proof, proffered under Rule 43(c),

F. R. C. P. included published statements favoring segrega

tion purportedly made by various governmental officials

including Governor Barnett,23 then Lt. Gov. Johnson,24 U. S.

22 In sustaining objection, the trial judge advised that based

on his long practice in Mississippi, he personally knew the Report

was untrue, an indictment of the State Judiciary (R. 1175), and

a “ loose-lipped remark by some irresponsible sources . . . reflecting

on the honesty and integrity of dedicated men who sit on the

trial benches in this state” (R. 1309). But see United States v.

Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. 353 (B. D. La. 1963), for an extensive

quote from a Civil Rights Commission Report at 359.

23 “ Gov. Ross Barnett of Mississippi said today some ‘weaklings’

and ‘moderates’ in the South may have become resigned to de

segregation but the big majority of the people are still firm

in their belief that integration is wrong.” Daily News, May 27,

1963 (P i’s. Prof. Exh. 10). See also P i’s. Prof. Exhs. 9-8, 12, 13,

14,15,16,17).

24 The “ disgraceful and unlawful actions of the agitators brings

shame and disgrace upon the Negro race.” Daily News, April 5,

1963 (P i’s. Prof. Exh. 11). And in a political ad acknowledged

by Governor Johnson’s campaign manager (R. 1236) a 1963 scala

wag was defined as: “ A white southerner who acts as a Republican

in an attempt to divide our white conservatives at a time when

the south needs to stand united against its enemies in both the

27

Senators and Congressmen from Mississippi,25 a County

Judge before whom most of the demonstration cases were

tried (R. 1341),26 and the Commissioner of the State De

partment of Welfare.27 Additionally proffered was testi

mony to show that the published views of influential leaders

in the community also support segregation. These included

the President of the Mississippi Farm Bureau,28 President

of the Mississippi Association of Methodist Ministers and

National Republican and National Democratic parties” (P i’s. Prof.

Exh. 25).

25 United States Congressman John Bell Williams, in criticizing

the spread of integration, predicted that “ the present national ad

ministration intends to enter every area of social life with a hopeful

plan to give the Negro preference over the whites” (P i’s. Exh. 9-3),

and following President Kennedy’s national televised address on the

Meredith case, five of Mississippi’s Congressmen and the State’s

two Senators issued a statement expressing their “ full and emphatic

disagreement with the position taken by the President” (P i’s. Prof.

Exh. 9-4).

26 Hinds County Judge Russell Moore criticized the Federal

Government’s action at Oxford as a ruthless campaign conducted

at bayonet point “seeking to indoctrinate our youth in race mix

ing, socialistic theories and the infallibility of the Federal Gov

ernment.” He indicated the theories are “ repugnant to them, their

families and the people of this state.” Clarion-Ledger, Oct. 10,

1962. (P i’s. Prof. Exh. 9-1.)

27 The Commissioner was reported as predicting that integration

means closing Mississippi’s public schools, adding “ The white race

possesses the brains, wealth, and the earning capacity to devise

a system of private schools to educate its children.” He said there

has been a concerted effort to hide and conceal from the American

people the differences which God ordained between the races. He

viewed as the major issue “ How much longer the white population

of Mississippi will continue to consent to be taxed and drained

of its sustenance for the benefit of a race and nation which shows

no appreciation for their sacrifices in order to destroy itself by

integration” (P i’s. Prof. Exh. 20).

28 The Daily News on Nov. 13, 1963, reported that the Farm

Bureau had given $10,000 to aid in the fight against the Civil

Rights Bill and quoted the President as warning that the bill

“ will destroy your way of life,” and will lead to a Communist

regime (P i’s. Prof. Exh. 23). The President denied the $10,000

aid but acknowledged the accuracy of the balance of the article

(R. 1233-34).

28

Laymen and other church groups,29 Editor of the White

Citizens Council newspaper,30 and the Jackson Junior

Chamber of Commerce.31

To show that statements of public officials contained in

the news clippings were typical and representative of Mis

sissippi officials, and that a critical view of opinions and

views expressed in the clippings is rarely heard (R. 1295-

96), appellants called Dr. Charles N. Fortenberry, Chair

man of the Department of Political Science at the Univer

sity of Mississippi, and co-author of the only available

book on Mississippi government which is used in a number

29 A Mississippi association composed of Methodist Ministers and

Laymen requested its legal advisory committee to move in the

courts against efforts by NAACP, CORE, and the National Coun

cil of Churches to integrate worship services (P i’s. Exh. 20-A).

Mrs. Hastings Kendall, a leader in the Women’s Society of the

Galloway Memorial Methodist Church, signed a resolution de

ploring the use of money raised by the local church by agencies

of the Methodist Church to further racial agitation— this following