Order Granting Motion for Hansen to Appear Pro Hac Vice

Public Court Documents

April 27, 1995

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Order Granting Motion for Hansen to Appear Pro Hac Vice, 1995. 8267f2f6-a746-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/071b7eba-2f59-4b6b-ac2c-889fad0a34e4/order-granting-motion-for-hansen-to-appear-pro-hac-vice. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

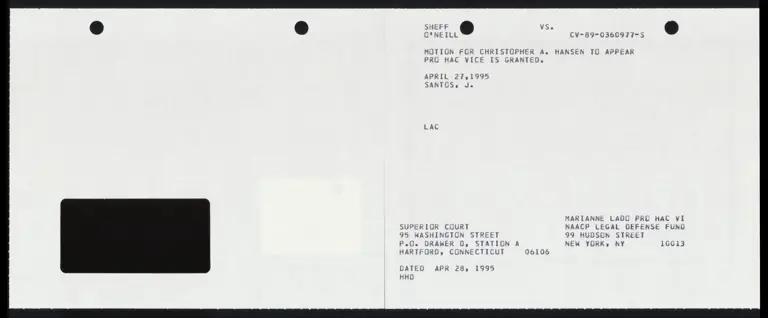

» * err @ . » O'NEILL CV-89-0360977-5

MOTION FOR CHRISTOPHER A. HANSEN TO APPEAR

PRO HAC VICE IS GRANTED.

APRIL 27,1995

LAC

| MARIANNE LADO PRO HAC VI

SUPERIOR COURT NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

95 WASHINGTON STREET 99 HUDSON STREET

P.O. DRAWER D, STATION A NEW YORK, NY 16013

HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT 06106

DATED APR 28, 1995

HHD

STATE OF conor —@ SS

U.S. POSTAGE

JUDICIAL BRANCH -rnnp-

PAID ONE OUNCE

DRAWER N, STATION A iD ae

HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT 06106 wm—— ;

HARTFORD, CONN.

NOTICE

THE JUDICIAL BRANCH IS COMMITTED TO THE EXPANDED

UTILIZATION OF ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION (ADR)

PROGRAMS TO FACILITATE THE EXPEDITIOUS AND EQUITABLE

RESOLUTION OF CASES.

FIRST CLASS MAIL

UPON AGREEMENT OF THE PARTIES, ANY CIVIL OR FAMILY

MATTER IS ELIGIBLE TO BE REFERRED TO AN ADR PROGRAM.

WHEN A CASE IS REFERRED ALL COURT PROCEEDINGS,

INCLUDING SHORT CALENDAR ASSIGNMENT AND DORMANCY

DISMISSAL, WILL BE STAYED. THE COURT WILL SET A TIME LIMIT

JA-0014 REV. 7/93

ON THE DURATION OF THE REFERRAL CONSISTENT WITH 75 \ fet

APPLICABLE RULES AND STATUTES. | NU

| SA

A RESOURCE LIST OF COURT AND PRIVATE ADR PROVIDERS IS |

AVAILABLE IN EACH JUDICIAL DISTRICT CLERK'S OFFICE. |

| TO;

|

IMPORTANT NOTICE

ON REVERSE Si Ih aa ka ihe

|