Rust v Sullivan Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

July 27, 1990

36 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rust v Sullivan Brief Amicus Curiae, 1990. 775b6d67-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/073c81d4-26c1-4d8e-997a-3ab45c0f9471/rust-v-sullivan-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

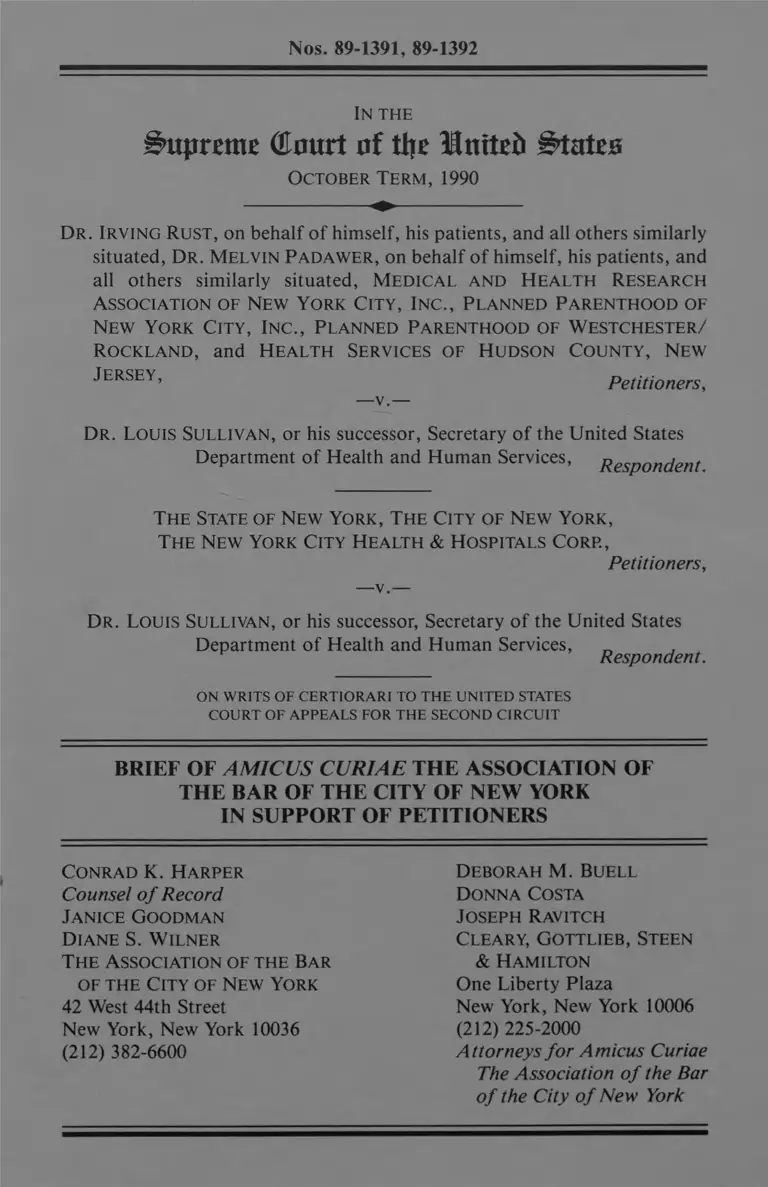

Nos. 89-1391, 89-1392

In the

Supreme Court uf tire United States

October Term, 1990

Dr . Irving Rust, on behalf of himself, his patients, and all others similarly

situated, Dr. Melvin Padawer, on behalf of himself, his patients, and

all others similarly situated, Medical and Health Research

Association of New York City, Inc., Planned Parenthood of

New York City, Inc., Planned Parenthood of Westchester/

Rockland, and Health Services of Hudson County, New

Jersey,

—v.—

Petitioners,

Dr . Louis Sullivan, or his successor, Secretary of the United States

Department of Health and Human Services, Respondent

The State of New York, The City of New York,

The New York City Health & Hospitals Corp.,

Petitioners,

Dr . Louis Sullivan, or his successor, Secretary of the United States

Department of Health and Human Services, Respondent.

ON w r it s o f c e r t io r a r i t o t h e u n it e d states

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF AM ICUS CURIAE THE ASSOCIATION OF

THE BAR OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

Conrad K. Harper

Counsel o f Record

Janice Goodman

Diane S. Wilner

The Association of the Bar

of the City of New York

42 West 44th Street

New York, New York 10036

(212) 382-6600

Deborah M. Buell

Donna Costa

Joseph Ravitch

Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen

& Hamilton

One Liberty Plaza

New York, New York 10006

(212) 225-2000

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

The Association o f the Bar

o f the City o f New York

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................ iii

INTEREST OF AMICUS.................... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT................... 5

ARGUMENT

THE REGULATIONS VIOLATE THE

FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHTS OF

HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS............ 6

A. The Censorship Prescribed By

The Regulations Violates The

First Amendment's Prohibition

Against Content-Based Speech

Restrictions..................... 6

1. The Regulations Violate

The First Amendment By

Prohibiting Discussion Of

Abortion..................... 6

2. The Regulations Violate

The First Amendment By

Requiring Title X Providers

To Communicate An Anti-

Abortion Message To Their

Clients...................... 9

i

3. The Speech Prohibited By

The Regulations Warrants

Particularly Strong

Protection Because It

Involves Communications

Between Health Care

Professionals And Their

Clients..................... 16

B. By Restricting Communications

Between Health Care

Professionals And Their Clients,

The Regulations Represent An

Unprecedented And Unauthorized

Intrusion Of Federal Power Into

The Health Care Field.......... 21

CONCLUSION........................... 28

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Akron v. Akron Center for

Reproductive Health Inc..

462 U.S. 416 (1983)..... 19, n.12,

Bigelow v. Virginia. 421 U.S. 809

(1975).............................

Cobbs v. Grant. 8 Cal.3d 229,

502 P .2d 1, 104 Cal. Rptr 505

(1972)........................... 24

Consolidated Edison Co. v. Public

Service Comm'n. 447 U.S. 530

(1980).......................... 6,

Cornelius v. NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund Inc.. 473 U.S.

530 (1980).........................

FCC v. League of Women Voters.

468 U.S. 364 (1984)................

Hammonds v. Aetna Cas. and

Sur. Co.. 243 F. Supp. 793

(N.D. Ohio 1965)................. 18

Harris v. McRae. 448 U.S. 297

(1980).........................12-13

Hickman v. Tavlor. 329 U.S. 495

(1947)............................18

Maher v. Roe. 448 U.S. 297

(1977)........................ 12-13

iii

Pages

20-21

___7

n. 14

11-12

. . . 11

10-11

n. 11

, n. 9

n. 11

, n. 9

Massachusetts v. Secretary of

Health and Human Services. 899

F. 2d 53 (1st Cir. 1990)........... 9 n.7

New York v. Sullivan. 889 F.2d

401 (2d Cir. 1989)......... 8 n.6, 9 n.7

Perry v. Sindermann. 408 U.S. 593

(1972) ................................ 15

Planned Parenthood of Chicago

Area v. Kempiners. 568 F. Supp.

1490 (N.D. 111. 1983)............. 7 n.5

Planned Parenthood of Cent.

Missouri v. Danforth. 428 U.S. 52

(1976)................................. 21

Police Dep't of Chicago v, Moslev.

408 U.S. 92 (1972)..................... 6

Roe v. Wade. 410 U.S. 113

(1973) .......................... . n. 12

Sherbert v. Verner. 374 U.S. 398

(1963)................................ .

Thornburgh v. American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

476 U.S. 747 (1986)................ 20-21

United States v. Larionoff. 431 U.S.

864 (1977).............................22

Webster v. Reproductive Health

Services. 109 S. Ct. 3040

(1989)........................ 12-13 , n. 9

Whalen v. Roe. 429 U.S. 589 (1977)_____20

IV

Woolev v. Mavnard. 430 U.S. 705

(1977)......................... 13-14

YWCA of Princeton v. Kualer. 342

F. Supp. 1048 (D.N.J. 1972),

aff'd. 493 F .2d 1402 (3d Cir.),

cert, denied 415 U.S. 989 (1974)...7 n.5

Statutes and Regulations

Criminal Justice Act, 18 U.S.C.

§ 3 006A (1985)...................17 n. 10

42 C.F.R. § 59..................2 n.3, 8

9, n. 7

10 n. 8

53 Fed. Reg. 2 (1988).......... 2 n.3, 8

9, 10 n.8

N.Y. Pub. Health Law § 2805

(McKinney 1985 & Supp. 1988).... 24 n.14

Public Health Service

Act, 42 U.S.C. § 300

(1982 & Supp. 1986)........ 2 n.3, 9 n.7

24 n .13

Pub. L. No. 91-572, reprinted in

1970 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin.

News (84 stat. 1504) 1748......... 22-23

Legislative Materials

S.2108, 91st Cong., 2d Sess.,

reprinted in 116 Cong. Rec.

24093-94 (July 14, 1970)............. 23

v

Other Authorities

American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists, Standards for

Obstetric-Gvnecoloqical Services

(6th ed. 1985)....................24 n. 15

American Medical Association,

Principles of Medical Ethics

(1986)............................ 24 n. 15

Congressman J. Dingell, Letter

to Otis Bowen (Oct. 14, 1987)....26 n.16

Constitution of the Association

of the Bar of the City of New

York.............................. l, n. 2

New York State Bar Association,

Lawyer's Code of Professional

Responsibility.................... 25 n.15

vi

INTEREST OF AMICUS1

The Association of the Bar of

the City of New York (the "Association")

is an organization of over 18,000

lawyers. While most members practice in

the New York City metropolitan area, the

Association has members in nearly every

state and in forty countries. Two

important purposes of the Association, as

set forth in its Constitution, are

"promoting reforms in the law" and

"facilitating and improving the

administration of justice."2 The

Association accordingly has devoted

itself to supporting and defending

reforms in the law in cases of

1 Letters of consent to the filing of

this brief are being filed with the

Clerk of the Court pursuant to Rule

37.3 of the Rules of this Court.

Constitution of the Association of

the Bar of the City of New York,

Art. II.

1

substantial public importance before the

courts.

The Association is committed to

the right of freedom of expression and

believes that the challenged

regulations3 abridge the free speech

rights of both health care professionals

and their clients. The Association views

a restriction of this nature, promulgated

in this manner, as an alarming precedent

for professionals who provide any form of

counsel, as well as for the general

public. Indeed, many lawyers, because

they are employed by government-funded

The challenged regulations, 42 C.F.R.

§ 59, 53 Fed. Reg. 2,922 et seq.

(1988) (hereinafter the

"Regulations"), were adopted by the

Secretary of the United States

Department of Health and Human

Services (hereinafter the "Secretary")

pursuant to Title X of the Public

Health Service Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 300

et sea. (1982 & Supp. 1986)

(hereinafter "Title X").

2

entities, may fear the imposition of

analogous restraints on their freedom

fully to advise their clients as required

by state law and ethical obligations.

The Association is equally

committed to the principle of individual

liberty, including the constitutional

right of women to make reproductive

decisions, in consultation with their

physicians, free from governmental

coercion. The Association believes that,

by imposing content-based restrictions on

health care professionals' advice to

their clients, the Regulations

effectively deprive women of information

necessary to exercise their

constitutional right of reproductive

choice.

These issues are of great

significance to the Association. The

Association, through its Committees on

3

Civil Rights and Medicine and Law,4

therefore urges that the order of the

Court of Appeals of the Second Circuit

upholding the Regulations be reversed.

Conrad K. Harper, President of the

Association of the Bar of the City

of New York; Janice Goodman, Chair

of the Committee on Civil Rights;

Diane S. Wilner, Chair of the

Committee on Medicine and Law.

4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

By censoring the information

that Title X providers may give to their

clients, the Regulations impermissibly

violate the First Amendment rights of

health care professionals by placing

content-based restrictions on

professional/client communications,

thereby interfering with the confidential

relationship between health care

professionals and their clients. By

employing its administrative rule-making

power to promulgate the Regulations in

contravention of both the intent of

Congress and the First Amendment rights

of professionals, the Secretary has

exceeded the scope and purpose of Title X

and has illegally intruded upon the

health care field.

5

ARGUMENT

THE REGULATIONS VIOLATE THE

FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHTS OF

HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS

A. The Censorship Prescribed By The

Regulations Violates The First

Amendment's Prohibition Against

Content-Based Speech Restrictions

1. The Regulations Violate The

First Amendment By Prohibiting

Discussion Of Abortion________

The First Amendment expressly

forbids the government from restricting

expression because of "its message, its

ideas, its subject matter, or its

content." Police Dep't of Chicago v.

Moslev. 408 U.S. 92, 95 (1972) (city

ordinance prohibiting non-peaceful

picketing found unconstitutional). See

Consolidated Edison Co. v. Public Service

Comm'n. 447 U.S. 530 (1980) (content-

based regulation of speech is violative

of the First Amendment). The

dissemination of information about

6

abortion in particular is a protected

form of speech. Bigelow v. Virginia. 421

U.S. 809 (1975) (advertisement of

abortion services is a form of expression

protected by the First Amendment).5

It is not disputed that, under

the Regulations, Title X providers are

forbidden to speak about abortion. Even

if a client asks for factual information

about abortion, the professional may not

provide such information or refer her to

any source of abortion-related

See also YWCA of Princeton v. Kugler.

342 F. Supp. 1048 (D.N.J. 1972)

(statute forbidding a physician from

prescribing or advising a woman to

terminate her pregnancy chills First

Amendment freedoms), aff'd. 493 F.2d

1402 (3d Cir.), cert, denied. 415 U.S.

989 (1974); Planned Parenthood of

Chicago Area v. Kempiners. 568 F.

Supp. 1490, 1495 (N.D. 111. 1983)

(statute denying funds to agencies

providing abortion counseling and

referral with private funds

impermissibly penalizes free speech

rights).

7

Instead the client mustinformation.6

be told only "that the project does not

consider abortion an appropriate method

of family planning and therefore does not

counsel or refer for abortion." 42

C.F.R. § 59.8(b)(5), 53 Fed. Reg. at

2,945. Thus, the Secretary has expressly

censored all discussion of abortion by

health care professionals receiving Title

X funds. Such a prohibition, on its

face, violates the First Amendment right

The Regulations' ban of the word

"abortion" from the Title X provider's

office arguably has the absurd effect

of preventing health care

professionals who receive Title X

funds from providing their clients

with a local telephone reference

directory. New York v. Sullivan. 889

F .2d 401, 415 (2d Cir. 1990)

(Cardamone, J., concurring); id. at

416-17 (Kearse, J., dissenting in

part).

8

of free speech of these health care

professionals.7

2. The Regulations Violate The

First Amendment By Requiring

Title X Providers To

Communicate An Anti-Abortion

Message To Their Clients

The Regulations not only

prohibit health care professionals from

counseling women about abortion and

providing abortion referrals when

requested, 42 C.F.R. § 59.8(b)(5), 53

Fed. Reg. at 2,945, but compel anti

Furthermore, it is not the case, as

the court below implies, New York v.

Sullivan. 889 F.2d at 412, that the

Regulations apply only to the use of

federal funds. No Title X project is

completely funded by federal monies.

42 C.F.R. § 59.11(c). Title X

providers are required to receive

nonfederal funds equal to at least 10%

of the amount provided through Title

X. 42 U.S.C. § 300a-4. In fact,

federal funds account for only 50% of

the monies received by Title X

projects. Massachusetts v. Secretary

of Health and Human Services. 899 F.2d

53, 59 (1st Cir. 1990). Thus, the

Regulations restrict speech paid for

by private as well as public monies.

9

Thus, in additionabortion referrals.8

to violating the First Amendment's

prohibition against content-based speech

restrictions, the Regulations violate

this prohibition by impermissibly

regulating speech on the basis of an

anti-abortion viewpoint.

Constitutional principles

dictate that the allocation of public

funds may not be motivated by the desire

to suppress "unacceptable" lawful ideas

while subsidizing "acceptable" ones. FCC

v. League of Women Voters. 468 U.S. 364,

The Regulations direct that health

care professionals provide pregnant

women with information regarding

prenatal medical care necessary to

protect the health of the "mother" and

"unborn child," even when the woman

has announced her intention to obtain

an abortion, 42 C.F.R. § 59.8(a)(2),

53 Fed. Reg. at 2945, and require that

all pregnant women be provided with a

list of providers of prenatal care who

do not perform abortions. Id. at

§ 59.8(a)(3), 53 Fed. Reg. at 2938.

10

383-84 (1984). Through Title X, the

government funds the discussion of

pregnancy and reproductive health between

health care professionals and poor women.

Having opened this forum for discussion,

the government must maintain strict

viewpoint neutrality and ensure that the

information given therein is

nondiscriminatory. Cornelius v. NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund. Inc..

473 U.S. 788, 800 (1985).

In FCC v. League of Women

Voters. 468 U.S. 364, 383-84 (1984), this

Court struck down a ban on editorializing

by publicly-funded radio stations because

the ban was "motivated by nothing more

than a desire to curtail expression of a

particular point of view on controversial

issues of general interest . . . ." Id.

(quoting Consolidated Edison Co. v.

Public Service Comm'n. 447 U.S. 530, 546

11

(1980) (Stevens, J., concurring)).

Similarly, the Court should strike down

the Secretary's attempt to prohibit

communications which a health care

professional might believe, in his or her

professional judgment, is warranted by

the client's circumstances, but which the

Secretary feels furthers an

"unacceptable" viewpoint.

The Regulations cannot be

analogized to the government's failure to

subsidize the performance of abortions.

See Webster v. Reproductive Health

Services. 109 S. Ct. 3040 (1989); Harris

v. McRae. 448 U.S. 297 (1980); Maher v.

Roe. 432 U.S. 464 (1977). Although,

according to recent decisions of this

Court, the government is free to choose

which medical services it will fund, id..

the government cannot use its funding

power to override the First Amendment

12

rights of health care professionals. The

above—cited funding cases do not sanction

any interference with the First Amendment

rights of these professionals.9 The

Regulations, however, do not merely deny

funding for certain medical care, but

also force health care professionals to

communicate one-sided, government-

prescribed information in contravention

of their rights of free speech.

"[W]here the State's interest

is to disseminate an ideology, no matter

Webster, Harris and Maher did not

address the constitutionality of a

funding scheme which regulated the

speech of health care professionals.

However, in Webster, four Justices

noted that if the statute had been

interpreted by the state to "prohibit

publicly employed health professionals

from giving specific medical advice to

pregnant women," a serious

constitutional issue would have been

raised. 109 S. Ct. at 3060 (O'Connor,

J., concurring); id. at 3068-69 n.l

(Blackmun, Brennan and Marshall, JJ.,

concurring in part and dissenting in

part).

13

how acceptable to some, such interest

cannot outweigh an individual's First

Amendment right to avoid becoming the

courier for such a message." Woolev v.

Maynard, 430 U.S. 705, 717 (1977). By-

censoring the information that Title X

providers may give to their clients, the

Regulations impermissibly compel health

care professionals — viewed by their

clients as the source of accurate,

impartial medical information — to act

as the mouthpiece for the Secretary's

disapproval of abortion.

The government created and

funded Title X programs expressly to

provide a forum for the dissemination of

family planning information. The

Regulations, however, impose a viewpoint

bias on the communications between Title

X providers and their clients by funding

only those health care professionals who

14

undertake to express views acceptable to

the government. The government "may not

deny a benefit to a person on a basis

that infringes his constitutionally

protected interests — especially, his

interest in freedom of speech." Perrv v.

Sindermann. 408 U.S. 593, 597 (1972).

See also Sherbert v. Verner. 374 U.S.

398, 405 (1962) ("conditions upon public

benefits cannot be sustained if they so

operate, whatever their purpose, as to

inhibit or deter the exercise of First

Amendment freedoms"). The Regulations

impermissibly condition the receipt of a

government benefit — the Title X funds

— on the surrender of the constitutional

right to free speech and thereby violate

the First Amendment rights of health care

professionals.

15

3. The Speech Prohibited By the

Regulations Warrants

Particularly Strong Protection

Because It Involves

Communications Between Health

Care Professionals And Their

Clients________________________

The violation of the First

Amendment's prohibition against content-

based speech restrictions is particularly

egregious in this case because the

Regulations interfere with confidential

communications between health care

professionals and their clients. The

Regulations not only abridge First

Amendment rights but substantially

interfere with the goals of the health

care profession. There is no greater

assault on the practice of sound health

care than a regulation which restricts

free and open communication of lawful

medical options between health care

professionals and their clients and

16

thereby effectively compels these

professionals to violate their own

professional standards.10

As in the attorney/client

relationship, an essential aspect of the

physician/patient relationship is the

The Regulations would be analogous

to a government regulation

prohibiting a criminal defense

lawyer who is paid with funds

appropriated by the Criminal Justice

Act, 18 U.S.C. §§ 3006A, et sea.

(1985), from counseling his client

about his Fifth Amendment right to

refuse to testify on the grounds

that his testimony may tend to

incriminate him. Certainly, for the

government to condition a grant of

funding to lawyers on the deliberate

withholding of advice concerning a

course of action which is not only

lawful, but constitutionally

protected, would not only violate

the First Amendment rights of

individual lawyers but also would

constitute a dangerous assault on

the integrity of the legal

profession as a whole. However,

this is precisely the kind of

unacceptable restriction which the

Regulations impose on health care

professionals practicing in the area

of family planning.

17

ability of the physician and patient to

speak openly and freely with one another

with the guarantee that the content of

their communications will remain

confidential.11 Under the cloak of

confidentiality, a physician must provide

appropriate counseling and seek informed

consent for treatment.

The duty of health care

professionals to their clients is no

different when the information concerns

abortion and its alternatives. Indeed,

because of the particularly important

"The candor which [the promise of

confidentiality] elicits is

necessary to the effective pursuit

of health; there can be no

reticence, no reservation, no

reluctance when patients discuss

their problems with their doctors."

Hammonds v. Aetna Cas. and Sur. Co..

243 F. Supp. 793, 801 (N.D. Ohio

1965) ; cf. Hickman v. Tavlor. 329

U.S. 495, 510 (1947) ("it is

essential that a lawyer work with a

certain degree of privacy, free from

unnecessary intrusion").

18

nature of the speech involved in

communications between health care

professionals and their female clients

involving women's exercise of their

constitutional right of reproductive

choice,12 this Court has consistently-

struck down laws that require health care

professionals to disseminate biased or

incomplete information about abortion.

See Akron v. Akron Center for

Reproductive Health Inc.. 462 U.S. 416,

444-45 (1983) ("By insisting upon

recitation of a lengthy and inflexible

list of information [the statute]

unreasonably has placed 'obstacles in the

See Roe v. Wade. 410 U.S. 113, 165

(1973) (the abortion decision is

"inherently, and primarily, a medical

decision"); Akron v. Akron Center for

Reproductive Health Inc.. 462 U.S. at

443 ("It remains primarily the

responsibility of the physician to

ensure that appropriate information is

conveyed to his patient, depending on

her particular circumstances.").

19

path of the doctor upon whom [the woman

is] entitled to rely for advice in

connection with her decision.'") (citing

Whalen v. Roe. 429 U.S. 589, 604 n.33

(1977)); Thornburgh v. American College

of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 476

U.S. 747, 762 (1986) (requirement that a

physician provide a woman with a list of

agencies offering alternatives to

abortion is "nothing less than an

outright attempt to wedge the

[government's] message discouraging

abortion into the privacy of the informed

consent dialogue between the woman and

her physician"). Like the statutes

struck down in Akron and Thornburgh. the

Regulations place an impermissible

"straitjacket" on health care

professionals and directly interfere with

the delivery of information which is

essential to the professional/client

20

relationship. Thornburgh. 476 U.S. at

762 (quoting Planned Parenthood v.

Danforth, 428 U.S. 52, 67 n.8 (1976)).

B. By Restricting Communications

Between Health Care Professionals

And Their Clients, The Regulations

Represent An Unprecedented And

Unauthorized Intrusion Of Federal

Power Into The Health Care Field

In passing Title X, Congress

did not intend either to restrict the

First Amendment rights of health care

professionals or to use appropriated

funds as a means of regulating the

medical profession. Neither the statute

nor its legislative history demonstrates

any congressional intent to interfere in

the communications between professional

and client. Notwithstanding the lack of

congressional intent and direction, the

Secretary has promulgated unprecedented

rules which, as described above, have the

direct effect of regulating the

21

physician/patient relationship in the

area of reproductive choice. The

Regulations are therefore invalid not

only because they transgress established

First Amendment freedoms, but because

they represent an unprecedented and

unauthorized intrusion of federal power

into the health care field.

Where an administrative agency

has exceeded its authority by

promulgating regulations that are

inconsistent with congressional intent

and "contrary to the manifest purposes of

Congress in enacting [the statute]," the

regulations are invalid. United States

v. Larionoff. 431 U.S. 864, 873 (1977).

Here, in adopting Title X, Congress

sought, among other things, to provide

"comprehensive, voluntary planning

services to all persons in the United

States," Pub. L. No. 91-572, reprinted in

22

1970 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News

(84 Stat. 1504) 1748, so as to "guarantee

the right of the family to freely

determine the number and spacing of its

children with the dictates of its

individual conscience." Preamble to S.

2108, 91st Cong., 2nd Sess., reprinted in

Cong. Rec. 24093-94, (July 14, 1970).

The Regulation directly contravenes the

congressional purpose by converting Title

X into a platform for dictating the

government's view of family planning and

by restricting the individual's ability

to "freely determine the number and

spacing of its children."13

The statutory basis offered by the

Secretary for the Regulations is

Section 1008, which forbids funding

any program "where abortion is a

method of family planning." 42

U.S.C. § 300a-6. This section clearly

does not provide a basis for the

restrictions on the communications

between professionals and clients now

at issue.

23

The scope of a health care

professional's duty to communicate with

his or her client has historically been

determined through state law and

professional self-regulation. Whether

governed by state laws of informed

consent,14 or the obligations of

professional ethics,15 the health care

See, e.q.. N.Y. Pub. Health Law

§ 2805-d (McKinney 1985 & Supp. 1988)

(requiring health care providers to

inform patients of all risks and

benefits of a particular mode of

treatment); Cobbs v. Grant. 8 Cal.3d

229, 243, 502 P.2d 1, 10, 104 Cal.

Rptr 505, 514 (1972) (recognizing a

"duty of reasonable disclosure of the

available choices with respect to

proposed therapy").

American Medical Association,

Principles of Medical Ethics 8.07

(1986) ("The physician's obligation is

to present the medical facts

accurately to the patient."); American

College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists, Standards for

Obstetric-Gynecological Services 76-77

(6th ed. 1985) (requiring, in the

event of unwanted pregnancy, that

physician counsel patient about her

options, including the option of

24

profession has always provided whatever

information is required in order for the

patient to choose freely the appropriate

treatment. The law and custom that

protect professional/client

communications are areas where the

federal government has never sought to

intervene.

Given the history of local and

self-regulation of health care

professionals and the absence of any

indication by Congress that it intended

to break with that history, it is clear

that Congress has not affirmatively

chosen to regulate physician/patient

communications. Instead, the Secretary

abortion); cf. New York State Bar

Association, Lawyer's Code of

Professional Responsibility. EC 7-8

("A lawyer should exert his best

efforts to insure that decisions of

his client are made only after the

client has been informed of relevant

considerations.").

25

has abused his rule-making power by

intruding on the physician/patient

relationship and placing unconstitutional

content-based and viewpoint-based

restrictions on the most important form

of speech employed by the health care

profession in a manner which Congress

neither mandated nor envisioned.16

The Regulations, promulgated

under a statute designed to fund family

planning services for impoverished women,

represent an illegal, as well as unwise,

extension of bureaucratic, rule-making

power beyond its appropriate sphere.

Allowing the Secretary to promulgate

these regulations would set a remarkable

Congressman John Dingell, the sponsor

of Section 1008, now suggests that the

Secretary may have intentionally

"misinterpret[ed] the congressional

intent for Title X." Congressman J.

Dingell, Letter to Otis Bowen (Oct.

14, 1987) at 2.

26

precedent for administrative agencies to

exercise power not only to restrict

protected speech but to dictate novel and

uniform standards of care across an

entire spectrum of professional activity

which Congress has never before sought to

occupy and certainly did not intend to

invade in enacting Title X.

27

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the

Association, through its Committees on

Civil Rights and Medicine and Law, urges

this Court to reverse the decision of the

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,*

Conrad K. Harper

Counsel Of Record

Janice Goodman

Diane S. Wilner

THE ASSOCIATION OF THE BAR

OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK

42 West 44th Street

New York, New York 10036

(212) 382-6600

Deborah M. Buell

Donna Costa

Joseph Ravitch

CLEARY, GOTTLIEB, STEEN

& HAMILTON

One Liberty Plaza

New York, New York 10006

(212) 225-2000

Date: New York, New York

July 27, 1990

* Counsel wish to acknowledge the

assistance of law clerks Taina

Bien-Aime and Matthew Weil in the

preparation of this brief.

28

RECORD PRESS, INC., 157 Chambers Street, N.Y. 10007 (212) 619-4949

81005 • 52