Coleman v. Carr Reality Order and Plaintiffs' Opposition to Motion by Defendant for Summary Judgment

Public Court Documents

August 4, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Coleman v. Carr Reality Order and Plaintiffs' Opposition to Motion by Defendant for Summary Judgment, 1978. 4a1e29ed-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0758a2e7-1ab2-4460-9a4f-dc1286b9bb45/coleman-v-carr-reality-order-and-plaintiffs-opposition-to-motion-by-defendant-for-summary-judgment. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

r r

r

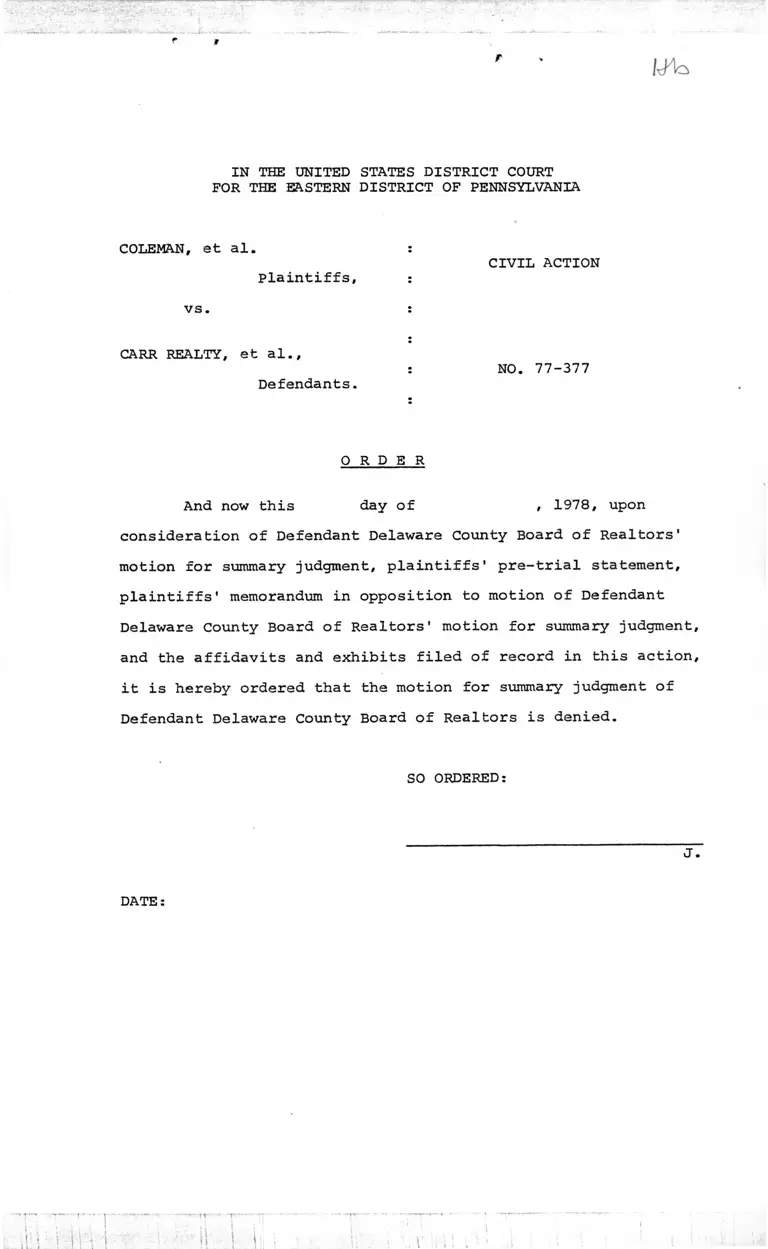

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA

COLEMAN, et al.

Plaintiffs,

vs.

CARR REALTY, et al.,

Defendants.

CIVIL ACTION

NO. 77-377

O R D E R

And now this day of , 1978, upon

consideration of Defendant Delaware County Board of Realtors'

motion for summary judgment, plaintiffs' pre-trial statement,

plaintiffs' memorandum in opposition to motion of Defendant

Delaware County Board of Realtors' motion for summary judgment,

and the affidavits and exhibits filed of record in this action,

it is hereby ordered that the motion for summary judgment of

Defendant Delaware County Board of Realtors is denied.

SO ORDERED:

J.

DATE:

r

t

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA

ELVIN COLEMAN, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

CARR REALTY, et al.,

Defendants.

CIVIL ACTION

NO. 77-377

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned certifies that on this date he served

attached Plintiffs' Memorandum in Opposition to Motion of

Defendant Delaware County Board of Realtors for Summary

Judgment by mailing true and correct copies thereof to the

defendants at the following addresses:

Barbara W. Mather, Esq.

Pepper, Hamilton & Scheetz

2001 Fidelity Bldg.

123 South Broad Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19109

Stephen S. Smith, Esq.

Baile, Thompson, Shea,

Craine & Smith

306 S. 69th Street

Upper Darby, Pa. 19082

Lionel A. Waxman, Esq.

23 E. Front Street

Media, Pennsylvania 19063

Max W. Gibbs, Esq.

Sand, Gibbs, Marcu & Smilk

6910 Ludlow Street

Upper Darby, Pa. 19082

DATED: August 4, 1978

Robert W. Costigan, Esq.

Costigan, Garber & Rubin

600 Penn Square Bldg.

Philadelphia, Pa. 19107

James S. Kilpatrick, Esq.

Haws & Burke

15 Rittenhouse Place

Ardmore, Pennsylvania 19003

Gilbert Newman, Esq.

Shralow & Newman

Third Floor

510 walnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19106

William D. North, Esq.

Kirkland & Ellis

200 East Randloph Street

Chicago, 111. 60601

BETH J. LIEF

Attorney for Plaintiffs

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA

ELVIN COLEMAN, et. al., :

Plaintiffs, :

CIVIL ACTION

V. No. 77-377

CARR REALTY, et. al.,

Defendants. :

PLAINTIFFS' OPPOSITION TO MOTION

BY DEFENDANT DELAWARE COUNTY BOARD

OF REALTORS FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

I. INTRODUCTION

In February, 1977 a black homeowner, a black

homeseeker, and an interracial fair housing council,

filed suit against six^named realtors and defendant

Delaware County Board of Realtors, challenging defen

dants ' policy and practice of racial discrimination

in housing against blacks in Eastern Delaware County.

In this action, plaintiffs seek damages, and

declaratory and injunctive relief to uproot defendants'

custom, policy and practice of racial discrimination

in the sale and rental of housing; and to remedy not

only the principal effect of such discrimination, which

is to exclude blacks from white neighborhoods, but also

the accompanying effects, which are, where possible, to

1/ One of the defendants Carr Realtors entered into a

Consent Decree with plaintiffs an June 12, 1978. During

the course of discovery, Plaintiffs learned that two of

the named defendants, Bruce-Hudson, Inc. and Dubson-Hudson

Realtors, are in fact part of the same corporation. See

Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement, II A 1-4, 10,pp . 6-7.

r

limit the opportunity of blacks to purchase homes to

a few black pockets and, generally, to discourage and

2/refuse to deal with black homeseekers. The action is

brought to enforce rights guaranteed by the Thirteenth

Amendment; 42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1982, and 1985, and the

3/Fair Housing Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. §§3601 et. seq.

Named plaintiffs are Elvin Coleman, a black

4/ 5/homeowner, Janice Jackson, a black homeseeker, and

an interracial fair housing organization, the Lansdowne-

Upper Darby Area Fair Housing Council, Inc.

The Lansdowne-Upper Darby Area Fair Housing

Council is a non-profit membership corporation organized

under the Pennsylvania Non-Profit Corporation Law. Its

membership includes black and white residents of Eastern

Delaware County, including the individuals who conducted

the audits of the named defendant realtors, Janice

Jackson, Elvin Coleman and Margaret Collins. The Council

exists, inter alia, to help black and white persons

purchase homes in Eastern Delaware County with full

freedom of choice and without regard to their race or the

6 /racial composition of nieghborhoods.— Members of the

Lansdowne-Upper Darby Area Fair Housing Council, Inc.

have since the inception of the Council's predecessor

2/ Complaint,5 5I, 61 at pp. 1, 18-20.

3/ Id.. 52 at p . 2.

4/ Plaintiffs Pre-Trial Statement, II at p. 1.

5/ Id., 12 at p. 1.

6/ Id., 13 at pp. 1-2.

-2-

groups in 1956, sought to and aided black persons and

interracial couples in the exercise of and enjoyment of

their right to integrated neighborhoods. As a major part

of such efforts, the Council over the years has conducted

and continues to conduct audits or tests of realtors who

are members of defendant Delaware County Board of Realtors

to determine the existence of racially discriminatory prac

tices. Where such audits or tests evidence racial discrimi

nation, the Council seeks to eradicate such discrimination

through the filing of complaints, primarily in administra

tive forums. Members of the Council purchased and continue

to live in racially segregated communities as a result of

defendants' policies and practices. As a result of these

policies and practices, members of the Council have been

denied their right to have housing available to them without

regard to race; have been deprived of the social benefits

of living in an integrated community; have been frustrated

in their goals of open and integrated housing; and have been

frustrated in their right to enforce and to aid in the

Venforcement of the right to equal opportunity in housing.

Named plaintiffs sue on their own behalf and on

behalf of a proposed class consisting of all (i) black

homeseekers who are currently seeking or who have sought

homes in Eastern Delaware County; (ii) black homeseekers

7/ Id., 13, 17, 18, VI C 1, VI C 11, at pp. 2-3, 49,

51, see affidavit of Carie Eisard, attached as Exhibit A

to this Memorandum.

- 3 -

who desire or have desired to purchase homes in Eastern

Delaware County but have been deterred from seeking such

homes; and (iii) current and prospective residents of

Eastern Delaware County who are injured as a result of

the "policies and practices complained of herin." (Com

plaint, 53a at p .2 )

There is substantial segregated housing in Eastern

Delaware County, an area of approximately twenty-five

square miles which lies immediately adjacent to metro-

8 /politan Philadelphia- Eastern Delaware County has

transportation facilities and roads which provide easy

access to downtown Philadelphia, has a wide variety of

housing for sale in different price ranges, and a sub

stantial number in the range suitable for families of

9/ . .moderate means. Despite the desirability of Eastern

Delaware County arising from the number of moderately

price homes, its schools and shopping and proximity to

Philadelphia, Eastern Delaware County is— with the

exception of a few, known and defined black areas— an

exclusive enclave for white persons.

The named defendant realtors foster and maintain

this pattern of segregation and exclusion by engaging

"in a custom, pattern and policy of willfully and

wantonly excluding blacks from white communities in

Eastern Delaware County . . . and the companion customs

8/ Id., 14 at p .2; Complaint, 514 at p. 6.

9/ Pre-Trial Statement, 15 at p. 2; Complaint 515 at p. 6.

-4-

patterns and policies of limiting black homeseekers

to virtually all-black areas, discouraging and refusing

to deal with blacks, and directing white homeseekers

10/away from black neighborhoods.

The methods by which defendant realtors pursue

their discriminatory patterns and policies include, but

are not limited to:

"a; refusing to show and/or discouraging

black or interracial homeseekers from

purchasing houses in white neighbor

hoods ;

"b. refusing to show and/or to offer to

show as many houses to black or

interracial homeseekers as to white

prospective homeseekers regardless

of the actual availability of houses

for sale in the price range and area

requested;

"c. aggressively pursuing white homeseekers

to maximize the possibility of their

purchasing houses in the white communi

ties specified above while making little

or no effort to similarly encourage

black homeseekers;

"d. directing blacks to houses in predominantly

black neighborhoods;

"e. refusing to show and/or discouraging whites

from purchasing houses in predominantly black

neighborhoods."ii/

Evidence as to the discriminatory methods of the

defendant realtors is overwhelming.

The individual experiences of discrimination suffered

by named plaintiffs, Elvin Coleman and Janice Jackson are

detailed in the complaint at 55 24-55 at pp. 9-16 and in

Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement at IIIA at pp. 28-32 and

IIB, IIIB, IVB and VB at pp. 7-8, 17-19, 33 and 39-40.

10/ Complaint, f20 at p. 7.

11/ Id., 523 at pp.8-9.

- 5 -

In addition, members of the Lansdowne-Upper Darby Area

Fair Housing Council, Inc., as part of their effort to

aid in the enforcement and enjoyment of fair housing laws,

tested the named realtor defendants in April and May, 1976.

Their role involved posing as prospective homeowners in

visits to defendant realtors. Couples of different races

expressed similar preference as to size, price range and

general location of houses in which they would be interested.

The Council members who participated in the tests were

instructed to and did immediately after their experiences

with defendant realtors record the facts as to those

12/experiences. in virtually every instance, defendant real

tors and their sales agents discriminated against black

persons and interracial couples, by one or more of the

13/five methods listed above, and/or by direct racial slurs.

Both the complaint and Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial

Statement also detail the discriminatory role of defendant

Delaware County Board of Realtors.

While plaintiffs will not repeat all facts as to

the Board which are set forth in their Pre-Trial Statement,

a brief summary of the facts supporting their claim is

appropriate.

12/ Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement, 17-8 at pp. 2-3.

13/ See Id., as to defendants Bruce Hudson, Inc. and

Dubson-Hudson Realtors, IIC, pp8-13; as to defendant Spano

Real Estate Company, IIIC, pp. 19-24; as to defendant Wm. C.

Taylor, Inc., successor to Wm. C. Taylor, Real Estate-Insurance,

IVC. pp. 33-36; and as to defendant Arthur J. Wagner, VD.pp. 41-44.

- 6 -

Defendant Delaware County Board of Realtors

(hereinafter referred to as "Board") is a Pennsylvania

coproration, whose members include over two hundred

individuals and organizations engaged in the real estate

business, including the named defendant realtors, princi

pals of those realtors, and real estate salespersons. The

Board's principal place of business is 10 East Spraul Road,

Springfield, Pennsylvania.

Defendant Board is an important arm of the real

estate industry in Eastern Delaware County.Membership

in its rank is considered a part of being in the business

_ , 13/of real estate. Each of the named defendant realtors

are not only members of defendant Board, but each of the

principals of the named defendant realtors are and have

14/

been on various committees of the Board. D. Louis Grady,

principal of defendant Spano Real Estate Company had held

every office at the Board, including that of President in

15/

1977, although Spano Real Estate has had a continuous

16/

history of discriminatory real estate practices.

From the 1950's on, defendant Board has actively

17/ 18/

opposed and attempted to frustrate passage and enforcement

of fair housing laws. The By-Laws of the Board provides for

suspension, expelsion on other disciplinary action for infrac

tion of standards of practice or unethical conduct, including

13/ E.g. deposition of Majorie Megraw, p. 6 ; Carl Ruchr,

p. 13; Betty McGinnis, pp.5-6.

14/ Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement, VI A at pp. 47-48.

15/ Id.. at VI A. 2 at p. 47.

16/ Id. at III A. 7-8, B-C, pp. 16-23.

17/ Id. at VI B. at p. 49.

18/ Id. at VI C-D at pp. 49-54.

- 7 -

racially discriminatory actions, while disciplinary

action is taken with great regularly against Board members

20/in areas of commission disputes and cooperative sales';—

the Board purposely avoids even the pretense of applying

its by-laws to realtors and salespersons who discriminate

21/against blacks even where it had personal knowledge that

discrimination has occurred or that a member has been

22/found guilty of violating the fair housing laws. Consistent

with its determination to thwart the goals of the fair

housing laws, the Board has continuously refused to

participate in efforts to achieve and foster open, integrated

23

1 9 /

housingrr to overcome its discriminatory image by encouraging

24/black homeseekers to purchase in Eastern Delaware Countyr

and to allow fair housing realtors access to its Multiple

. 25/Listing Service.

Despite the efforts of the Board, cited above, to

insulate its members from discipline for discriminatory

conduct and to frustrate the goals of the fair housing

laws, members of the Boards including some of the named

defendant realtors, had been cited in administrative and

judicial forums for engaging in racial discrimination

19/ By-Laws, Delaware County Board of Realtors, Article

XVI, Section 4; Article VI, Section 6 ; National Association

of Realtors Code of Ethics, Article 10, See Id. at VI D 1-3

at p. 53.

20/ See Minutes Professional Standards Committee, Delaware

County Board of Realtors.

21/ Plaintiffs’ Pre-Trial Statement, VI D 4-7, at pp. 53-54.

22/ Id.

23/ Id., VI E at pp. 55-56.

24/ Id.

25/ Id., VI F-G, at pp. 57-61.

- 8 -

violative of the state and federal fair housing laws.

2 6 /

The basis of many of these complaints was evidence

gathered from testing member realtors. The Board there

fore set out through a series of actions to have all

27/

such testing stop and/or become ineffective. The means

of doing this included not only direct pressure on the

Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission, but also on

28/

state and federal legislators and the United States

29/

Department of Justice. The Board thus acted, and

conspired with and on behalf of its members to end the

most effective way of uncovering its discriminatory

30/

•practices. Where testing had already led to a finding

of probable cause against one of its members and a

amend defendant, Bruce Hudson, the Board and its members

agreed to pressure for and succeeded in attaining a

cessation of all further investigation by the Pennsyl

vania Human Relations Commission and, indeed, in having

31/

two cases actually dropped.

26/ Id. VI C 1 at p. 49.

27/ Id. VI C at pp. 49-52.

28/ Id. VI C 10 at p. 50.

29/ Id. VI C 19 at p. 52.

30/ Id. VI C at pp. 49-52.

31/ Id. VI C 11-16.

-9-

II. STATUS OF THIS ACTION

Presently pending before this Court is Plaintiffs'

Motion for Determination of Class and various motions of

32/

defendants to dismiss and/or for summary judgment. At the

time of oral argument on these motions, this Court ruled that

the determination on all motions be stayed pending completion

of discovery by all parties in conformance with the order

of this Court. Pursuant to this Court's order, plaintiffs

33/-

filed a detailed Pre-Trial Statement by July 3, 1978.

Defendants were not required to submit a counter Pre-Trial

Statement and were given the opportunity to file Supplemental

Memorandum in support of their motions by July 21, 1978.

In light of the detailed facts set forth in Sections

I, II, III, III A, IV, V of Plaintiffs Pre-Trial Statement

and defendant realtors' failure to supplement their various

motions or in any way to contest the facts set forth therein,

plaintiffs contend that all motions to dismiss and/or for

summary judgment by said realtor defendants must be denied.

In addition, plaintiffs rely on their previously submitted

34/

memoranda in opposition to defendant realtors' motions.

32/ Motions to Dismiss by defendants Bruce Hudson, Dubson-

Hudson, Taylor and Wagner; Motions for Summary Judgment by

defendants Bruce Hudson, Dubson-Hudson, Spano. Taylor and

Wagner. In addition, plaintiffs have pending a Motion to

Compel and for sanctions against Wm. C. Taylor.

33/ Plaintiffs do not contend that they had less than

ample time to complete discovery. Plaintiffs therefore

decline to respond to the gratuitous and irrelevant "history"

of discovery as set forth in the July 21, 1978 Supplemental

Memorandum in Support of Delaware County Coard of Realtors'

Motion for Summary Judgment.

34/ See July 21, 1978 Supplemental Memorandum in Support of

Delaware County Board of Realtors' Motion for Summary Judgment

[hereinafter referred to as Board Memorandum], page 6 .

- 10 -

,i;, I: I l / I '1 !

Plaintiffs1 present memorandum therefore is addressed only

to claims against defendant Board and the conspiracy claim

against all defendants, including defendant Board.

III. DEFENDANT DELAWARE BOARD OF REALTORS

CONTINUES TO IGNORE AND FAILS TO MEET

THE LEGAL STANDARDS GOVERNING DISPOSITION

OF MOTIONS FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT IN CIVIL

____________RIGHTS CASES________________

A. The Legal Standards

As the Supreme Court stated in Adickes v. Kress & Co.,

398 U.S. 144, 157, 161 (1970), "[a]s the moving party,

[defendant Board of Realtors] had the burden of showing

the absence of a genuine issue, as to any material fact";

and "[t]he party moving for Summary Judgment has the burden

to show that he is entitled to judgment under established

principle and if he does not discharge that burden, then

he is not entitled to judgment."

That burden is a particularly great one in a civil

rights case such as the instant action. Where controversies

over constitutional rights are at stake, a court must

rigorously insure against granting summary judgment when any

doubt exists concerning disputed material facts, see Perry

v. Sinderman, 408 U.S. 593, 598 (1972); Boulware v. Bottaglia,

344 F.Supp. 889, 892-893 (D.Del. 1972) aff'd, 478 F.2d 1398

(3d. Cir 1973) (per curiam).

As in complex antitrust litigation, in this complex

civil rights action, "[S]ummary procedure should be used

sparingly . . .where motive and intent play leading roles.

Thus, "It is especially in civil rights disputes that we

ought to be chary of disposing of the case on pre-trial motions."

- 1 1 -

Sisters of Prov. of St. Mary of the Woods v. City of Evanston,

335 F.Supp. 396 (N.D. 111. 1971) and in housing discrimination

cases, like the instant action "[s]ummary judgment is rarely,

if ever, appropriate." Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority,

265 F.Supp. 582, 584 (N.D. 111. 1967); United States v. Mitchell.

327 F.Supp. 476, 483 (N.D. Ga. 1971).

In siim, as Justice, then Judge, Stevens stated in a

case involving a claim of housing discrimination:

"Our task when reviewing a summary

Judgment is, of course, quite different

from the review of a judgment entered

after a ful trial. We must view the

evidence, and the inferences which may

be drawn therefrom, most favorably to

the party against whom the summary judg

ment was entered. Moreover, when the

ultimate factual issue may turn on an

appraisal of the defendants' motivation,

it is especially important not to fore

close cross-examination and the adversary

testing of the evidence 'in front of the

trier of fact who can observe the demeanor

of the witness." Wang v. Lake Maxinhall

Estate, Inc., 531 F.2d 832, 835 (7th Cir.

1976).

B. Defendant Board Of Realtors Fails

To Meet Its Burden On A Motion

For Summary Judgment_____________

Defendant Board ignores the principles cited above

or attempts to dismiss them by a citing at page 8 of its

memorandum a few instances in which summary judgment has

been granted. The mere fact that Rule 56 motions succeeded

35/

in whole or in part in those cases is of absolutely no aid

35/ The Court of Appeals in O'Malley v. Brierly, 477 F.2d

785 (3d. Cir. 1973) reversed the grant of summary judgment

in part of the case and remanded the issue to the district

Court. Moreover, with the exception of the decision in

Wheatley Heights Neighborhood Coalition v.Jenna Resales Co.,

Prentice Hall Equal Opportunity in Housing Reporter 1113,757

(E.D.N.Y. 1976), none of the cases cited by defendant either

involve claims of housing discrimination or are remotely ana

logous to the instant action. As will be demonstrated infra,

the majority of plaintiffs claims against the Board are totally

unlike the issues in Wheatley and, in any event, the facts and

legal bases proffered of plaintiffs in that case are unlike

those present in the instant action.

- 12 -

. C< . ■ : ■ i ._____ Z__ \i Vl I

to the Board's present motion for, of course, the facts in

each case and the claims they support must be individually

analayzed pursuant to the standards set forth in III A,

supra.

distort the allegations of the complaint and mischaracterizes

the facts as set forth in Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement,

The Board fails to acknowledge that it , along with the de

fendant realtors, is responsible for pervasive patterns

and policies of classwide housing discrimination in Eastern

Delaware County. The Board's memoranda focuses on "the

experiences of the two individual plaintiffs"; it completely

ignores the facts in Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement which

establish a systematic pattern of housing discrimination

Coleman and Ms. Jackson with the defendant realtors, all

active members of the Board, document the consequences of the

Board's facilitating discrimination in real estate, and pro

tecting and insulating its members from enforcement of the

right to equal opportunity in housing.

allegation as set forth in Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement.

(Indeed, if it were to contest a material fact directly,

the Board would automatically strike a fatal blow to its motion.)

However, defendant in fact does dispute material portions of

plaintiffs' allegations, but couches that dispute in broad,

unsupported statements, in answer to facts which

36/ Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement, e.g.II C, III C,

IV C, V C and D.

As in its earlier memoranda, the Board continues to

as well as experiences of Mr.

The Board does not directly dispute a single

establish that the Board used negotiation opportunities

with the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission in order

to have cases against its members discontinued, and to have

testing of its members cease or become ineffective, defendant

boldly stated that such negotiations constituted "good faith

efforts to institute an affirmative action program." (Board

Memorandum, p. 25). While plaintiffs' specific claims are

discussed in detail. Point IV infra, it is important to note

thet in this and other statements throughout its brief, the

Board ignores the rule that it "has the burden to show he

is entitled to judgment under established principle. . ."

Adickes v. Kress & Co., supra; and that the inferences which

may be drawn from the evidence must be viewed" most favor-

bly to the party against whom summary judgment [is sought."

Wang v. Lake Maxinhall Estate, Inc., supra.

Furthermore, for the major part of its argument, pages 18-37,

the Board fails to cite a single case brought pursuant to the

fair housing laws, yet without authority, makes wholesale

statements that sections of Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement

are "frivolous" and "meritless." For example, point VI B of

Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement states that the Board actively

opposed passage not only of the Pennsylvania Fair Housing Law

but also the federal civil rights housing bill. in response,

the Board contends that these facts "are patently frivolous . . .

[and] totally irrelevant." (Memorandum, p. 18.) However, federal

courts in fair housing and other civil rights cases disagree

with defendant and have given weight to the fact that a defendants's

image was discriminatory and the defendant did nothing to change

that image.

- 1 4 -

Unites States v. R^al Estate Development Corp., 347 F.Supp.

776, 782 (N.D. Miss. 1972); accord, United States v. Medical

Society of South Carolina, 298 F.Supp. 145 (D.S.C. 1969).

The Board's failure to portray the facts accurately

or to contest them with supportable documents; or to cite

cases brought under the federal fair housing statutes, 42

U.S.C. §§1981, 1982 and 3601 et. seq.. which support its

motion for summary judgment makes it clear that it has not

carried its burden under Rule 56. Nor, as the remainder of

plaintiffs1 memoranda demonstrates, can the Board overcome

that burden, for the facts set forth in Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial

Statement establish that the Board has violated plaintiffs'

rights under 42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1982 and 1985, and the Title

VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. §§3601 et. seq.

IV. DEFENDANT DELAWARE COUNTY BOARD OF REALTORS

CONSPIRED AND ACTED TO STOP TESTING OF ITS

MEMBER REALTORS AND INTERFERE WITH ENFORCEMENT

OF THE RIGHT TO FAIR HOUSING IN VIOLATION OF

TITLE VIII OF. THE ,FAIR HOUSING ACT___________

A. The FactsSet Forth In Plaintiffs' Pre-

Trial Statement Establish Actions By

Defendant Board To Stop Testing Of Its

Members, And To Frustrate The Effectiveness-

Of Testing In Order To Insulate And Protect

Its Members From Investigation Of Discrimi

natory Practices And Enforcement Of the Fair

Housing Laws________________________________

The facts set forth in section VI C. of Plaintiffs'

-15-

liHi \ ■ \ i ; : 1 \ } \

Pre-Trial Statement are evidence, inter alia, that:

" 32/(1) The Board knew that testing had

revealed the discriminatory practices

of its member realtors toward blacks;

(2) the Board knew that this evidence

from testing had led to the filing of

complaints in the Pennsylvania Human

Relations Commissions,

(3) the Board knew that many such complaints

had resulted in findings of probable

cause, cease and desist orders or consent

decrees;

(4) the Board wanted to stop testing of its

members in order to insulate and protect

them from investigation of discriminatory

practices and enforcement of the fair

housing laws;

(5) the Board knew that the Pennsylvania

Human Relations Commission wanted the

Boarg to sign a Memorandum of Understand-

ing;=«f Relating to the Fair Housing Laws;

(6) the Board agreed to and did use the

Commission's desire to sign a Memorandum

of Understanding to pressure the

Commission to cease testing of its members;

(7) the Board further discussed putting

pressure on the Commission to cease

testing by contacting state and federal

legislators;

(8) residents of Eastern Delaware County, who

were and are members of plaintiff Lansdowne-

Upper Darby Area Fair Housing Council had

filed complaints against Board members at

the Commission;

37/ "Testing" or "Auditing" in housing is a practice to determine

whether a realtor or apartment owner in engaging in discrimina

tory treatment in violation of the Fair Housing Law. The

description of testing by the Court in United States v. Youritan

Construction Co., 370 F.Supp. 643, 647, aff ‘d . 509 F.2d 623

(9th Cir.1975) provides a general understanding of testing:

[T]esters' . . .visited various of defendants' buildings

to inquire about the availability of apartments for rent

[or houses for sale]. The testers' method was to have

a black applicant and a white applicant, usually of the

same age and sex [and similar characteristics] inquiry

of [the availability of] an apartment [or house]. . . "

38/ a copy of the Memorandum of Understanding is found at

Board's Appendix, Exhibit 6 .

-16-

(9) the Board pressured and succeeded in

having the Commission drop pending

cases, based on testing by both the

Commission and members of plaintiffs

council against defendant W. Bruce

Hudson as a condition to his signing

the Memorandum of Understanding;

(10) After the Memorandum was signed,

testing of Board members by the

Commission ceased, and the cases

against defendant W. Bruce Hudson

became inactive or was closed,

without public hearing, or any order;

39/

(11) the Board unanimously agreed to work

together to achieve an end to all testing.

B. Testing For Racial Discrimination In

Housing Is A Protected Activity Under

Title VIII Of The Civil Rights Act Of

1968; Actions To Interfere With That

Right Are Prohibited By 42 U.S.C. $3617.

Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C.

§3601 provides:

"It is the policy of the United States

to provide, within constitutional limi

tations, for fair housing throughout

the United States."

To achieve this policy, the provisions Title VIII prohibit

a comprehensive range of discriminatory practices. See 42

U.S.C. §§3604-3606. To assure that persons could enforce

the rights established by Title VIII, Congress also provided:

"It shall be unlawful to coerce, intimidate,

threaten or interfere with any person in

-the exercise or enjoyment of, or on account

of his having aided or encouraged any other

person in the exercise or enjoyment of, any

right granted or protected by section 3603,

3604, 3605, or 3606 of this title. This

section may be enforced by appropriate civil

action." 42 U.S.C. §3617.

39/ The above list of facts is based on facts contained

in Section VI C of Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement. For

the Convenience of the Court, this section is annexed as

Exhibit B.

-17-

The actions taken by the Board, to have testing of its

members cease, and to frustrate and render ineffective

testing of its realtor members by interfering with

Plaintiffs * rights to exercise and aid in the exercise and

enjoyment of rights under 42 U.S.C. §§ 3603-6, violated

§3617.

Testing has been specifically held to be a legally

protected activity under §3617. Northside Realty Associates.

Inc., v. Chapman, et. al.,411 F.Supp. 1195 (N.D. Ga 1976).

Northside Realty Associates arose under the following

relevant facts: The United States filed a motion for

civil contempt against Northside alleging that the

defendants had violated the terms of a permanent injunction

enjoining violations of the Fair Housing Act. To establish

the grounds for comtempt, the United States submitted the

affidavits of testers who had participated in auditing

Northside for compliance with the Fair Housing Act. Through

discovery in the contempt action, Northside learned of the

testing activity and brought suit against the testers,

seeking damages for interference with economic relations,

trespass,and other grounds. The testers alleged that

their activities were expressly protected by the Fair Housing

Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. §§3601 et. seq; and that the suit

against them violated the right conferred by §3617 to

exercise and aid others in the exercise and enjoyment of the

right to equal housing opportunity. The district Court

held that, just as similar language in §1973 i(b) of the

Voting Rights Act creates a legal right for persons aiding

any person to vote to be free from intimidation, threats

-18-

foror coercion, so, too, §3617 creates a legal right

testers to be free from coercion, intimidation or in

terference in their activity. 411 F.Supp. at 1198.

Likewise, obstacles to testing were found to be

contrary to the Fair Housing Act in United States v.

Wisconsin, 395 F.Supp. 732 (W.D. Wise. 1975). In hold

invalid a State statute which barred testing, the district

court found:

4 0 /

"Section 101.22(4m) makes it

difficult if not impossible for persons

seeking housing without discrimination

based on race, color, religion or

national origin to determine whether

unlawful discrimination has been prac

ticed against them and chills the

exercise of the right to equal housing

opportunity. . . [and] the statute must

be viewed as an obstacle to the accom

plishment of the principal objective of

Congress in passing the Fair Housing Act,

that is, to provide fair housing through

out the United States." Id. at 733,734.

The basis for the holdings in Northside Realty, supra,

and United States v. Wisconsin, supra, has been consistently

recognized by federal courts.

Despite the broad protection afforded black homeseekers

by Title VIII and 42 U.S.C. §§1981 and 1982, acts of racial

discrimination are often difficult to prove,

housing today is often disguised or subt

since racism in

Testing of real

tors for evidence of housing discrimination, such as that

40/ Rachel v. Georgia, 384 U.S. 780 (1966)? Thompson v. Brown,

434 F.2d 1092 (5th Cir. 1970); Whatley v. City of Vidalia,

399 F .2d 521 (5th Cir. 1968).

41/ United States Commission on Civil Rights, Understanding

Fair Housing 15 (1973).

- 1 9 -

—T

conducted by plaintiff Lansdowne-Upper Darby Area Fair

Housing Council is key to proving, and thereby eliminating

discriminatory conduct in a world where defendants are

unlikely to admit racial motivation for their actions or

differential treatment between black and white homeseekers.

The vital role that "testing" evidence plays in enforcement

of the right of blacks to equal opportunity housing has been

widely recognized and appreciated by the federal courts:

"The Fair Housing Act of 1968 was intended

to make unlawful simpleminded as well as

sophisticated and subtle modes of discrim

ination. It is the rare case today where

the defendant either admits his illegal

conduct or where he sufficiently publicizes

it so as to make testers unnecessary. For

this reason, evidence gathered by a tester

may, in many cases, be the only competent

evidence available to prove that the defen

dant has engaged in unlawful conduct." Zuch

v. Hussey 394 F.Supp. 1028, 1051 (E.D. Mich.

1975), aff'd. 547 F.2d 1168 (6th Cir. 1977).

The Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit has asserted that

"[i]t would be difficult indeed to prove discrimination in housing

without this means of gathering evidence." Hamilton v. Miller,

477 F.2d 908, 910-1 n.l (10th Cir. 1973). In a case where

a white woman served as a "tester" after a black man sus

pected that he was denied an apartment because of racial

discrimination, the Eight Circuit declared, "The use of

checkers in this situation is well established and has been

recognized as necessary under similar circumstances,"

Wharton v. Knefel, 562 F.2d 550, 554 (8th Cir. 1977).

Thus, "[ejvidence of the experiences of white and

black 'testers* or 'checkers' has been uniformly admitted

into evidence to show the existence of a discriminatory policy."

United States v. Youritan Constr. Co., supra, 370 F. Supp.

at 650; Wharton v., Knefel, 562 F.2d at 554;

- 20 -

Smith v. Anchor Building Corp., 536, F .2d 231, 234 (8th

Cir. 1976); Hamilton v. Miller, 477 F.2d at 909; Johnson

v. Jerry Pals Real Estate, 485, F.2d 528, 530 (7th Cir.

1973); Zuch v. Hussey, 394 F.Supp. at 1051; Williamson

v . Hampton Management Co., 339 F.Supp. 1146, 1148 (N.D.

111. 1972); Brown v. Balias, 331 F.Supp. 1033, 1035

(N.D. Tex. 1971); Bush v. Kaim, 297 F.Supp. 151, 155-6

(N.D. Ohio 1969); Harris v. Jones, 296 F.Supp. 1082,

1083 (D. Mass 1969); Newbern v. Lake Lorelei, 308 F.Supp.

407, 415 (S.D. Ohio 1968); see also Hughes v. Dyer, 378

F.Supp. 1305, 1308 (W.D. Mo. 1974).

Most recently, the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

regarded testing as so crucial to enforcement of the fair

housing laws that it held testers have standing to challenge

racially discriminatory behavior. Meyers v. Pennypack Woods

Home Association, 559 F.2d 894, 898 (3d. Cir.1977). The

Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in similarly holding

that testers have standing under the fair housing laws stated

"What the testers did was to generate

evidence suggesting the perfectly permissible

interference that the defendants have been

engaging, as the complaints allege, in the

practice of racial steering with all of the

buyer prospects who come through their doors.

Racial steering, by its nature, is a subtle

form of discrimination that is difficult if

not impossible to prove otherwise than by

comparing the areas to which homeseekers of

different races are directed." Village of

BeUwood v. Gladstone Realtors. 569 F.2d 1013,

1016 (7th Cir. 1978, cert, granted. ____U.S.

______(1978) .

C. Defendant Board's Argument As To

Plaintiffs' Claim Is Without Merit;

At The Least, Triable Issues Of Fact

Are Raised Which Preclude Summary Judgment

Defendant Board seeks to obfuscate its illegal conduct

by ignoring the facts set forth in plaintiffs' Pre-Trial

- 21 -

I '

r

claim is based on the execution of the Memorandum of

Understanding itself. (July 21, 1978 Memorandum in Support

of Boards Motion for Summary. Judgment, p. 25.) That is,

set forth in Plaintiffs’ Pre-Trial Statement establish,

defendant Board unlawfully sought and seeks to interfere

with the right of plaintiffs to foster fair housing and

eradicate discrimination through testing and use of testing

to obtain relief at the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission.

It is true that most of the Board's actions took place in

the context of negotiation and discussion of the Memorandum

of Understanding, but it is those actions and not the Memorandum

itself, which violates Title VIII of the Fair Housing Laws.

The Board admits, "There is no question but that Board

members disliked the testing that was occurring in Delaware

County." Indeed, defendant further acknowledges that the reason

the Board members disliked testing was:

". . . a lot of members were confused

about what the law really was in the

sale of housing; and. . . because of

the misunderstanding that existed, not

only by professionals but by owners as

well, . . . the human relations people

were very often coming into offices and

testing." (Deposition of James J. Pace.

Chairman of the Board's Equal Opportunity

Committee, page 59, cited in the Board's

Memorandum at page 28.)

42/ It is worth note that Defendant Board conveniently refers

to Plaintiffs' Answer to the Board's Interrogatories and ignores

Plaintiffs' Detailed Pre-Trial Statement (July 21, 1978

Memorandum in Support of Board's Motion for Summary Judgment,

p. 25) .

43/ Thus, the explicit wording of the Memorandum of Understand

ing set forth at pages 26-27 of defendants' Memorandum is

basically irrelevant.

quite simply, as the facts

- 2 2 -

Ten years after the passage of Title VIII and the decision

of the Supreme Court in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.. 392

U.S. 409 (1968), discriminatory conduct can hardly be

shielded by claims of "confusion". See Gore v . Turner,

563 F.2d 159, 164 (5th Cir. 1977). There is nothing

difficult to understand about a law which says that all

persons must be treated equally regardless of the color

of their skin.

The Board's general affirmation of good faith or denial

of discrimination cannot serve to rebut evidence of illegal

conduct, Alexander v. Louisiana. 405 U.S. 625, 632 (1972);

Turner v . Fouche, 396 U.S. 346, 361 (1970); Sims v. Georgia.

389 U.S. 404, 407 (1967); Williams v. Matthews, 499 F.2d

819, 827 (8th Cir. 1974). The Board never denies that

it conspired to and sought to interfere with testing and the

effectiveness of testing. Board Memorandum, p. 27.

However, to the extent that its assertions of good faith are

raised, genuine issues of fact exist which preclude a

grant of summary judgment.

Evidence listed in Plaintiffs1 Pre-Trial Statement

contradict the Board's assertion that the Pennsylvania

Human Relations Commission "steadfastly refused to enter

into any agreement to end testing and communicated that

refusal to the Board." (Board Memorandum, p.27 ). For

one thing, in January, 1975, the Board was told that

testing by the Commission had been temporarily cancelled.

(See Minutes January 21, 1975, Board of Directors, Delaware

County Board of Realtors, p.4. listed in Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial

Statement as Document 11, p. 63, attached as Exhibit C.)

- 2 3 -

Secondly, the activities of the Board after March 4, 1975

demonstrates that the Board did not consider the continuance

of testing as a fait accompli, for it continued to exert

pressure on the Commission. (See February 13, 1976 letter

of James J. Pace to Vincent Rossi, listed in Plaintiffs'

Pre-Trial Statement as Document 18, p. 64, attached as

Exhibit D. Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement VI C 10, p. 50.)

Thirdly, there are no facts that show Board members did not

see the negotiations involving the Memorandum as a protec

tive device. Indeed, the facts in Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial

Statement show the exact opposite. See e.g., VI C 12, p. 51

and Letter of James Pace, attached as Exhibit D. Finally,

the fact that Pace may receive reports of what Board members

believe to be testing proves nothing: those reports do

not claim the Commission is testing nor are they necessarily

accurate.

The Board does not deny it pressured the Commission

to drop cases against Bruce Hudson. Indeed, in the face of

Plaintiffs.' Pre-Trial Statement, VI C 11, 12, 13, 14, pp. 51-

52, it would be hard put to do so. The fact the Commission

acceded to the Board's pressure can in no way insulate the

interference with testing. Plaintiffs' claims are

not a "collateral attack" on the Commission; the cases cited

by the Board at page 31 of its Memorandum have absolutely

nothing to do with violations of 42 U.S.C. §3617. In

O'Burn v. Shapp, 70 F.R.D. 549 (E.D. Pa. 1976), plaintiffs'

non-minority police officers, sought to challenge a hiring

and promotion plan for minorities by the Pennsylvania State

Police, which was embodied in a consent decree. The Court

- 2 4 -

in O'Burn held that an independent suit was improper

because plaintiffs had the opportunity to contest the

decree in the original lawsuit. Similarly, in Black and

White Children of Pontiac School System v. School District

of Pontiac, 464 F.2d 1030 (6th Cir. 1972), the Court held;

"The proper avenue for relief [for] unanticipated problems

which had developed in the carrying out of the Court1s

order was an application to intervene and a motion for

additional relief in the principal case." Those cases in

no way deal with a claim of unlawful pressure to defeat

civil rights legislation. In any event, there is no

"consent decree" at issue in this case. Section 3617

prohibits interference with testing; plaintiffs' facts

demonstrate the Board took action to interfere with and

frustrate the testing and purpose of testing by plaintiff

Council. See affidavit of Carie Isard, attached as

44/

Exhibit A.

The Board finally cites anti-trust cases for the

proposition that their negotiations are privileged. The

Board's reliance is misplaced; each of those cases bases

its holding on the legislative history of the anti-trust

laws. E.g. Eastern Railway Presidents Conference v. Noerr

Motor Freight, Inc., 365 U.S. 127, 137 (1961) .

The Board concludes its argument with the unsupported

statement that it did not lobby for preferential treatment

with the Commission. (Board Memorandum, p. 32.) The simple

response is that Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement, VI C

44/ Linda R.S. v. Richard D , 410 U.S. 614 (1973), cited at

page 31 of the Board's Memorandum is, as the Board itself

states, irrelevant, since no claim is made against the

Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission.

- 2 5 -

H ' ‘ - T '7T—

disputes that and this denial consequently raises an issue

of fact that precludes summary judgment. More importantly,

the Minutes of the Board and the letter of James Pace to

the Commission on their face completely undercut the

45/

veracity of the Board's statement.

In sum, the facts in Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement

establish a concerted effort on the part of the Board to

interfere with testing and to frustrate the effectiveness

of the plaintiffs' right to aid in the enjoyment of equal

housing opportunity, in violation of 42 U.S.C. §3617. The

Board submits no evidence which does or could refute the

facts contained in Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement and

offers no civil rights or housing discrimination case law

contrary to plaintiffs' claim.

V. PLAINTIFFS HAVE PRESENTED FACTS WHICH

ESTABLISH A CONSPIRACY TO INSULATE MEMBERS

FROM COMPLAINTS OF HOUSING DISCRIMINATION

AND TO INTERFERE WITH TESTING IN VIOLATION

OF 42 U.S.C. §1985(3) .____________________

In response to this Court's order, Plaintiffs filed a

detailed Pre-Trial Statement which at VI clearly sets forth

46/

specific details constituting a violation of 42 U.S.C. §1985(3).

45/ The Board cannot rely on the affidavit of Raymond Cartwright.

At his deposition, he admitted that paragraphs 6a and 6b of

his affidavit were not based on personal knowledge. (Deposition,

pp. 60-61.)

46/ As stated in Plaintiffs' prior Brief In Opposition to

Defendants' Motion to Dismiss Complaint Under 42 U.S.C. §1985

For Failure to State a Claim Filed By Defendant Delaware County

Board of Realtors, the complaint easily meets the pleading

elements as set forth in Griffin v. Breckenridge. 403 U.S. 88

(1971). In any event, there is no doubt that the facts in

Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement meet those requirements and,

to the extent the Court may find the complaint per se deficient

the proper course at this juncture is to allow plaintiffs leave

to amend their complaint to conform to the evidence. Foman v,

Davis, 371 U.S. 178 (1962).

-26-

l

r i

j i *

The facts set forth in VI C, attached hereto as

Exhibit B clearly set forth a conspiratorial agreement

between the Board and named defendant realtors to cease

testing and to seek protection against complaints of

housing discrimination.

Section VI A of Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement

establishes the active involvement of the principals

of the defendant realtors in the Board. Section VI C

of Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement (annexed as Exhibit

B) not only establishes a violation of Title VIII (see

part IV of this memorandum, supra), but also establishes

a conspiracy between the Board and member realtors -

including the named defendant realtors - to violate

Title VIII by interfering with those who sought to

enforce the fair housing laws.

The relevant criteria to determine whether the facts

allege a conspiracy under §1985(3) are: (I) a conspiracy;

(2) for the purpose of depriving, either directly or

indirectly, any person or class of persons of the equal

protection of the laws, or of equal privileges and immuni

ties under the laws; (3) an act by any member of the

conspiracy in furtherance of the object of the conspiracy;

whereby (4) plainfiffs were deprived of having and exercising

any right or privilege of a citizen of the United States.

Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88,.102-103 (1971).

A. Conspiracy

The facts in VI C establish that the Board and its members,

including specifically D. Louis Grady (Spano Real Estate Co.)

and Bruce Hudson met and conspired:

1. The Equal Opportunity Committee of the

Board acted on behalf of the Board (VI C 3, 6 p. 49-50)

- 2 7 -

2. D. Louis Grady and Bruce Hudson

were members of the Equal Opportunity Committee.

(VI C 3)

3. The Equal Opportunity Committee

and Board wanted to stop testing because its mem

bers were being named as respondents and defendants

as a result of testing (VI C 1)

4. The Equal Opportunity Committee,

the Board and defendant realtors conspired to

use various means to stop testing. (VI C 10, 11, 19)

5. The Board conspired with Bruce Hudson

to pressure to have the cases against Hudson, which

had brought as a result of plaintiffs' testing, dis

continued without public hearing or consent decree.

(VI C 11)

The number of the defendant realtors on the Board, and on

the Equal Opportunity Committee, and the fact that the Equal

Opportunity Committee was acting on behalf of the Board, as

well as the express and implied agreements to work to stop

testing and have cases against Bruce Hudson dropped, clearly

establish a "conspiracy". In Adickes v. Kress, supra, a

white Mississippi "Freedom School" teacher with a group of

her black students alleged, inter alia, she was refused

service at a lunch counter and arrested as a result of a

conspiracy between Kress and the Hattiesburg, Mississippi police

Summary judgment was granted on the contention of Kress that

the teacher had no knowledge of any communication or agreement

between Kress employees and a policeman in the store, and

-28-

t

was relying on circumstantial evidence to support

the conspiracy allegation. The Supreme Court reversed.

"[WJ e conclude that respondent failed

to fulfill its initial burden of demon

strating what is a critical element in

this aspect of the case-that there was

no policeman in the store. If a police

man were present, we think it would be

open to a jury, in light of the sequences

that followed, to infer from the circum

stances that the policeman and a Kress

employee had a 'meeting of the minds'

and thus reached an understanding that

petitioner should be refused service.

Because '[o]n summary judgment the

inferences to be drawn fran the underlying

facts contained in [the moving party's]

materials must be viewed in the light most

favorable to the. party opposing the motion, '

United States v. Diebold, Inc., 369 U.S.

654, 655, 8 L. Ed. 2d 176, 177, 82 S Ct. 993

(1962), we think respondent's failure to show

there was no policeman in the store requires

reversal." 398 U.S. at 158-159.

The Board fails to allege that defendant realtors were

not present during the meetings of the Equal Opportunity

Committee and/or the Board of Directors. Under the

reasoning and holding of Adickes v. Kress, it is therefore

impossible to conclude at this time there was no "meeting

47/

of the minds."

B. Deprivation, Either Directly Or

Indirectly, Any Person Or Class .

Of Persons of Protected Rights

As point IV B of this memorandum, supra, demonstrates,

testing is a protected right under Title VIII, 42 U.S.C.

47 /_J A written agreement or even explicit agreement is

unnecessary to support a claim of conspiracy under §1985(3).

As the Court stated in Santiago v. city of Philadelphia.

435 F.Supp. 136, 155 (E.D. Penn. 1977): "Conspiracy in this

context [§1985 (3.)] means that the co-conspirators must have

agreed, at_ least tacitly, to commit acts which will deprive

plaintiff of equal protection of the law." (Emphasis added.)

- 2 9 -

§§3603-6 and any activities to interfere with testing

violates 42 U.S.C. §3617. The actions of the Board

described in Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement VI C (see

point IV A of this memorandum) did not occur in a

vacuum; the Board agreed--2 conspired - to work together

to have all testing cease, to minimize testing to the

greatest extent possible and to frustrate the purpose

of testing by having cases dropped which had been

brought as a result of testing. A violation of the

fair housing laws is plainly a deprivation of "equal

protection of the laws or of equal privileges." e . g,,

Progress Development Coro, v. Mitchell. 386 F.2d 222,

234 (7th Cir. 1961) (§1985(3) conspiracy by village

officials and others to prevent racially integrated

development) 7 Clark v. Universal Builders. Inc.. 409

F.Supp. 1274, 1278-79 (N.D. 111. 1976) (§1985(3)

conspiracy alleged by black homeseekers against builders

and realtors; "all of the elements necessary for an

action under 42 U.S.C. §1985(3) are present"); Planning

For People Coalition v. County of Dupage. Prentice-Hall

Equal Opportunity in Housing Rptr. 513,753 (N.D. ill.

1976) ( §1985(3) conspiracy to exclude blacks by county

and developers ) .

C. An Act By Any Member Of The Conspiracy

In Furtherance Of The Object Of The

Conspiracy____ __________ ______

Paragraph III c 12-13 of Plaintiffs Pre-Trial Statement

constitute acts in furtherance of the conspiracy:

12. On February 13, 1976, James Pace,

as Chairman of defendants' Equal Opportunity Committee,

wrote to Vincent Rossi, Housing Specialist, Pennsylvania

- 3 0 -

Human Relations Commission to secure information

as to how the signing of the Memorandum of Under

standing will affect "matters that are now pending

with the Human Relations Commission such as the

Hudson matter to present testing procedures and

protection against actions from the Justice

Department."

13. Sometime between February 13, 1976

and April 14, 1976, James Pace, as Chairman of

the Equal Opportunity Commission had a discussion

with Mr. Rossi to seek the discontinuance of the

cases against defendant Hudson."

These paragraphs set forth specific dates and events,

supported by documents, during which a member of the Board,

acting on behalf of the Board and defendant realtors, acted

to further the object of stopping testing and having

cases against Bruce Hudson dropped. Plaintiffs have thus

met the third requirement of §1985(3), "that one of them

performed an overt act in furtherance of that conspiracy"

Hisch v. Eastern Pa. Psychiatric Institute, 434 F.Supp.

963, 979 (E.D. Pa 1977).

D. Plaintiffs Were Deprived Of Their Rights

As discussed earlier at Part IV of this Memorandum,

interference with the right to test and the effectiveness

of testing deprived the members of plaintiff Lansdowne-Upper

Darby Area Fair Housing Council, Inc. of their rights under

42 U.S.C. §3617.

Plaintiffs establish far more than only that defendant

realtors have acted in similar ways. In sum, plaintiffs

have presented facts which establish a conspiracy to violate

plaintiffs' rights under 42 U.S.C. §3617 in violation of

§1985(3).

- 3 1 -

VI. DEFENDANT BOARD MISSTATES THE LEGAL

OBLIGATION OF REALTOR ASSOCIATIONS

AND MULTIPLE LISTING SERVICES UNDER

THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT_______________

The facts in Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement at VI

B, C, D, F 9 evidence a deliberate refusal to take any

action, consistent with its own by-laws and codes, against

members whom it has actual knowledge have discriminated

against blacks; an agreement and series of actions, instead,

to insulate its members from enforcement of fair housing

laws and thereby facilitate their illegal conduct; and

a refusal to instruct its members in the non-discriminatory

use of the services it provides.

Such conduct does not escape judicial scrutiny by the

Board's general contention that the Board has no affirmative

statutory obligation to police and enforce compliance with

the fair housing laws.

To begin with, the Board's own by-laws and code of ethics

belie its suggestion (Board Memorandum, p.4) that it does not

have authority to discipline its members for racially

discriminatory housing practices. The By-Laws of defendant

Delaware County Board of Realtors Article XVI, Section 4

provides:

"Any member may be suspended, expelled or

subjected to other disciplinary action for any in

fraction of the By-Laws or of duly promulgated rules,

regulations and standards of practice and business

conduct or for unethical conduct or for failure at

any time to meet and maintain all qualifications for

membership established by these By-Laws or by the

Director."

The By-Laws of defendant Delaware County Board of Realtors,

Article VI, Section 6 provides:

"Salesmen members shall maintain the same

high standards of ethical conduct in the real estate

business as is required of Active members."

-32-

• : i t 5 1 I \ b it i

Article 10 of the National Association of Realtors Code

of Ethics provides:

"The REALTOR shall not deny equal pro

fessional services to any person for reasons of

race, creed, sex or country of national origin."

In addition, the Board has a comprehensive set of rules and

regulations governing membership in and use of its Multiple

Listing Service, violation of which subjects a participating

48/realtor to disciplinary review.

In the face of these rules, the evidence demonstrates

the Board not only fails to discipline its members for actions

the Board knows are discriminatory, but, indeed, takes

affirmative sets to protect such members. The Board is

liable for this conduct under the fair housing laws.

The Civil Rights Act which form the predicate for

plaintiffs' claim, 42 U.S.C. §§1981 and 1982, and Title VIII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et. seq. ,

individually and together constitute a broad-based prohibition

of. segregation and discrimination in housing practices. As

the Supreme Court stated in Jones v. Alfred Mayer, 392 U.S.

409, 424, (1968):

"[Section 1982] plainly meant to secure

that right [to purchase and lease property

equally without regard to race] against

interference from any source whatever,

whether governmental or private. " (Emphasis added.)

In the words of Senator Trumball, sponsor of what became

§1982, that act "would affirmatively secure for all men,

whatever their race or color. . .the right to acquire

property. . .the right to enforce rights in the Courts, to

make contracts and to inherit and dispose of property."

Id., 392 U.S. at 432. (Emphasis added.)

48/ Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement, VI F 3.

-33-

: i ■ i M t

For persons to enjoy their guaranteed civil rights, they

also have to have the right to be free from actions which

facilitate or aid the violation of such rights. An argument

similar to the Boards', that aid to or facilitation of dis

criminatory conduct is not forbidden as long as the party did

not itself discriminate, was rejected by the Supreme Court in

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973). Plaintiffs in Norwood

challenged the receipt by private, segregated schools of text

books from the State. The State argued plaintiffs lacked a

cause of action because the State itself was not discriminating

and was merely providing educational tools to students, not

school. The Supreme Court agreed with plaintiffs that the

State's behavior violated their rights and stated:

"[I]t is also axiomatic that a State

may not induce, encourage or promote

private persons to accomplish what

it is constitutionally forbidden to

accomplish," citing Lee v. Macon

County Board of Education, 267 F.

Supp. 458, 475-476 (M.D. Ala. 1967)

Id., 413 U.S. at 465.

Accord, Bishop v, Starkville Academy, 442 F. Supp. 1176

(N.D. Miss. 1977) (3 Judge Ct.).

The facts in Plaintffs' Pre-Trial Statement VI D 4-6

establish:

"4. The Pennsylvania Real Estate

Commission determined by order dated

July 22, 1970 that Vincent Spano,

doing business at Spano Real Estate

Co., violated the Real Estate Brokers

License Act by purposely discrimina

ting on the basis of race and revoked

defendant Spano's real estate license.

"5. After the adjudication by the

Commission, defendant Delaware County

Board of Realtors took no disciplinary

action against either Vincent Spano,

Spano Real Estate Co., or D. Louis

Grady, Spano's designated broker."

34

"6. A special Spano committee of defendant

Board was formed but was immediately dis

banded when the revocation of Spano's

license was reversed in the Commonwealth

Court of Pennsylvania, although the basis

of the reversal was not that Spano was

innocent of the charges but that pro

visions for revocation could not be

retroactively applied."

A reasonable inference to be drawn from these facts is that

the purpose of the "special Spano committee" was to aid

Spano in fighting enforcement of the fair housing laws; in

light of the immediate disbandment of the committee after

Spano's technical victory, no other inference is reasonable.

In addition, although the Board frequently disciplines

members for disputes over commissions and the like, not

a single member has been disciplined for discriminatory

behavior, although the Board had actual knowledge of the

12/violations. The actions taken by the Board to protect

Bruce Hudson from a Commission hearing is a stark example

of the Board's aid to discriminating members. In general^

the Board's persistent condonation of its members'discrimi

natory behavior facilitates the perpetuation of such conduct;

absent discipline and enforcement of its own rules by this

important arm of the real estate industry in Eastern Delaware

County, members are given the "green light" by the Board

to continue their illegal ways.

That the Board's condonation may not be the "precise"

cause of racial discrimination by its members is irrelevant.

4t9/ Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement, VI D 7-8 at p. 54

VI C 11-14 at pp. 51-52.

-35-

l

■jrTirn m r.̂ ; - --. >**>; ••

"If the defendant is a private individual or a group of

private individuals seeking to protect private rights,

the courts cannot be overly solicitous when the effect is

to perpetuate segregated housing." Metropolitan Housihg

Development Corp. v. Village of Arlington Heights. 558

F.2d 1283, 1293 (1977); see Smith v. Anchor Building Corp..

supra. As the Supreme Court stated in Norwood v. Harrison.

supra. 413 U.S. at 465-466:

" . . . the Constitution does not permit. . .

aid [to] discrimination even when there is

no precise causal relationship between

state financial aid to a private school

and the continued well-being of that

school. . . if that aid has a significant

tendency to facilitate, reinforce and support

private discrimination." 2̂-/

Plaintiffs need not show that the Board intended to

facilitate or support discrimination. A showing of

discriminatory effect is sufficient to make out a case of

prima facie discrimination. E,g., Metropolitan Housing

Development Corp. v. Village of Arlington Heights, supra;.

Williams v. Matthews Co., supra, 499 F.2d at 826-828, cert.

denied, 419 U.S. 1021 (1974). For "[t]o insulate [an

organization of realtors] from Title VIII liability is to

retreat from the affirmative mandate of §3604(a)." Fair

Housing Council v. Eastern Bergen County Multiple Listing

Service, 422 F. Supp. 1071, 1075-1076 (D.N.J. 1976).

50 / The fact the Board is not a governmental body is

irrelevant to the application of Norwood to the instant

case. Norwood arose under 42 U.S.C. §1983 which is limited

to state actions; in contrast, 42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1982, and

3601 ejt. seg. apply to private bodies.

-36-

Defendant's reliance on Rizzo v. Goode, 423 U.S. 362

(1976) and Hollins v. Kraas. 369 F.Supp. 1355 (N.D. 111.

1973) is misplaced. The theory of liability rejected in

those cases assumed no knowledge of discriminatory behavior

and subsequent refusal to discipline pursuant to established

si/regulation. In contrast, the facts here evidence the

Board's failure to discipline in the face of knowledge

of discrimination and affirmative actions to protect

. 52/dis crimination.

The Board's condonation of the use of its Multiple

Listing Services cannot be separated from its general

condonation, facilitation and support of its members' dis

criminatory practices. Despite its knowledge of discrimi

nation on the part of its members, it refuses to insist or

ensure that the Service is used non-discriminatorly. Indeed,

the Board does not even instruct its members to do so.

Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement, VI F 9. This is not

surprising,since the person hired and paid by the Board to

5i/ Moreover, the scope of Rizzo has been seriously narrowed

by the Supreme Court's recent decision in Monell v. Dept.

of Social Services of the City of New York, 46 U.S.L.W. 4569

(June 6, 1978) which held a city liable under 42 U.S.C. §1983

for injury suffered, inter alia, as a result of policy or

customs which may fairly be said to represent official policy.

Id. at 4579.

5?/ The Board pleads:,innocence simply because its By-Laws

provide for written complaints; to allow defendants to

use such a rule to avoid responsibility in the face of actual

knowledge would fly in the face of the holdings and reasoning

in Norwood, supra. Arlington Heights, supra, and the other

cases cited immediately above. After all, nothing prevented

the Board from filing written complaints.

- 3 7 -

conduct its course on the Multiple Listing Service is

D. Louis Grady principal of Spano Real Estate Co., which

has had a continuous history of racial discrimination.

Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement, III, III A, VI D 4,

D 7, F 9.

The per se immunity claimed for the Multiple Listing

Service has been rejected on summary judgment in an

indistinguishable case. Fair Housing Council v. Eastern

Bergen County Multiple Listing Service, supra* see also

Singleton v. Gendason. 545 F.2d 1224, 1226-1228 (9th Cir.53/

1976) .

The Board's reliance on the recent decision in Wheatley

Heights Neighborhood Coalition v. Jenna Resales, supra, is

also misplaced. Unlike the present case, there was no

facts offered in Wheatley that the Board failed to instruct

participating members of the MLS to use the service in a

non-discriminatory manner; nor were there facts showing

that the entity which solely controlled the MLS, in this

case the Board, had fostered, facilitated and supported

discrimination by its members. The reluctance of the

Court in Wheatley to apply the theory of respondent superior

to an MLS (but not a Board of Realtors) is of no aid to

53/ Linmark Associates v. Township of Willingboro. 97

S.Ct. 1614 (1977) and New York Times Co, v. Sullivan,

376 U.S. 254 (1964) have no application here; no one

seeks suppression of any First Amendment right of the

Board or the Multiple Listing Service, nor can the Board

license discrimination, Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Human

Relations Commission. 413 U.S. 376 (1973)

- 3 8 -

defendant since plaintiffs here do not rest their claim

of that theory of liability but rather on the theory,

discussed supra, that the affirmative mandate of the fair

housing laws prohibit practices and actions which aid,

encourage or foster racial discrimination in housing.

The Board weakly attempts to dismiss portions of

Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement^ As stated previously,

it is indeed relevant that the Board actively fought

passage of laws prohibiting race discrimination in

housing. Also relevant is the consistent refusal to

and attempt to frustrate community efforts to foster

fair housing. See Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement

VI E. Courts have given wait to a defendant's discrimi

natory image and its failure to correct that image.

U.S. Real Estate Development Corp., supra, U.S. Medical

Society of South Carolina, supra.

Finally, the Board's attempt to use VI D 8 of

Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement to show that its members

engage in non-d is criminatory sales i.s absurd. For one

thing, such a statement hardly follows the principle

that inferences are to be drawn in a light most favorable

to the party against whom summary judgment is sought.

More importantly, the paragraph, is evidence that the

Board blackballs the unusual member who might sell a

black family a home in a white neighborhood.

In sum, plaintiffs facts constitute evidence of

violations of the fair housing laws.

-39-

VII. MATERIAL ISSUES OF FACT EXIST AS TO

WHETHER THE BOARD DISCRIMINATES IN

ITS. MEMBERSHIP AGAINST FAIR HOUSING

REALTORS _______________________

Part VI of Plaintiffs' Pre-Trial Statement and its

supporting documents present facts which give rise to

an inference that the Board denied membership and

participation in its Multiple Listing Service to Suburban

Fair Housing, Inc. and Margaret Collins because she was a

54/

fair housing realtor.

The Board's argument that there is no material issue

of fact as to the rejection of Ms. Collins' application

must fail. The theory in her suit against the Board,

Suburban Fair Housing, Inc, v. Delaware County Board of

Realtors was restraint of trade; the issue of discrimination

was never raised in the proceeding. That the Board

discriminatorily excluded Suburban Fair Housing, Inc.

and Ms. Collins is ultimately a legal conclusion rather

than a factual matter, so the Board's reliance is misplaced/

Moreover, the Board confuses the legal theory of the prior

lawsuit for the factual question of the Board's purpose

or motive for the exclusion; it is often the case that

54/ The fact that Ms.. Collins is white does not weaken

this claim. See, e,g., McDonald v. Sante Fe Trail Trans

portation Cp., 427 U.S. 273 (1976); Trafficante v. Metro

politan Life Ins. Co.. 409 U.S. 205 (1972).

-40-

i : r.r

every factual nuance is neither considered norrejected in

a particular legal theory. Of course, restraint of trade

and discrimination are not mutually exclusive. See, e.g..

Bratcher v. Akron Area Board of Realtors, 381 F.2d 723

(6th Cir. 1967) ("[AJppelants undertake to apply the anti

trust laws to an alleged conspiracy by a board of realtors

and others, which conspiracy allegedly prevents Negroes from

owning or renting property in white neighborhoods".)

The Board does not dispute that Suburban Fair Housing,

Inc.,was a realty corporation dedicated to ensuring that

black persons have a full and equal opportunity to

purchase homes of their choice, whatever the racial

composition of the neighborhood. At page 23 of its Memo

randum, the Board contests the fact that the rejection of

Ms. Collins for participation in the Multiple Listing

Service had a substantive debilitating effect on her

business. What the Board ignores, however, is that the

office of summary judgment is not to try issues of facts

but to determine whether any exists.

The self-serving statements by members of the Board

which deny that the rejection of Suburban Fair Housing,

Inc., had nothing to do with its announced and

publicized policy of fair housing cannot aid the Board.

Alexander v. Louisiana, supra; Turner v. Fouche. supra;

Sims v. Georgia, supra? Williams v. Matthews, supra.

- 4 1 -

9

Ms. Collins applied to defendant Board only after

winning her case against the Main Line Board of Realtors.

As a result of her suit against the Main Line Board, that

organization was ordered either to admit her as a member or

admit her as a member in its Multiple Listing Service. The

Main Line Board chose the latter route; had it admitted her

to full membership, the Delaware County Board could not

even pretend that her rejection was legitimate. However,

the plain import of the decision in Ms. Collins' case against

the Main Line Board was that she was entitled to full partici

pation in the Multiple Listing Service. Indeed, she informed

defendant Board that she was seeking admission either to the

Board or, in the alternative, to the Board's Multiple Listing

Service. The adament refusal of the Board in light of this

sequence of events clearly raises an inference that its

motives were predicated on other than on innocent motive.

In addition, plaintiffs maintain that the Board's rules,

insofar as they operate to preclude fair housing realtors

access to its Multiple Listing Service, runs afoul of the

fair housing laws. As stated earlier, actions which have a