Kankakee County Housing Authority v. Laural Spurlock Brief and Argument for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kankakee County Housing Authority v. Laural Spurlock Brief and Argument for Appellant, 1954. 939dfd90-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/07eb3979-c759-49e6-b23f-9ded917ab50c/kankakee-county-housing-authority-v-laural-spurlock-brief-and-argument-for-appellant. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

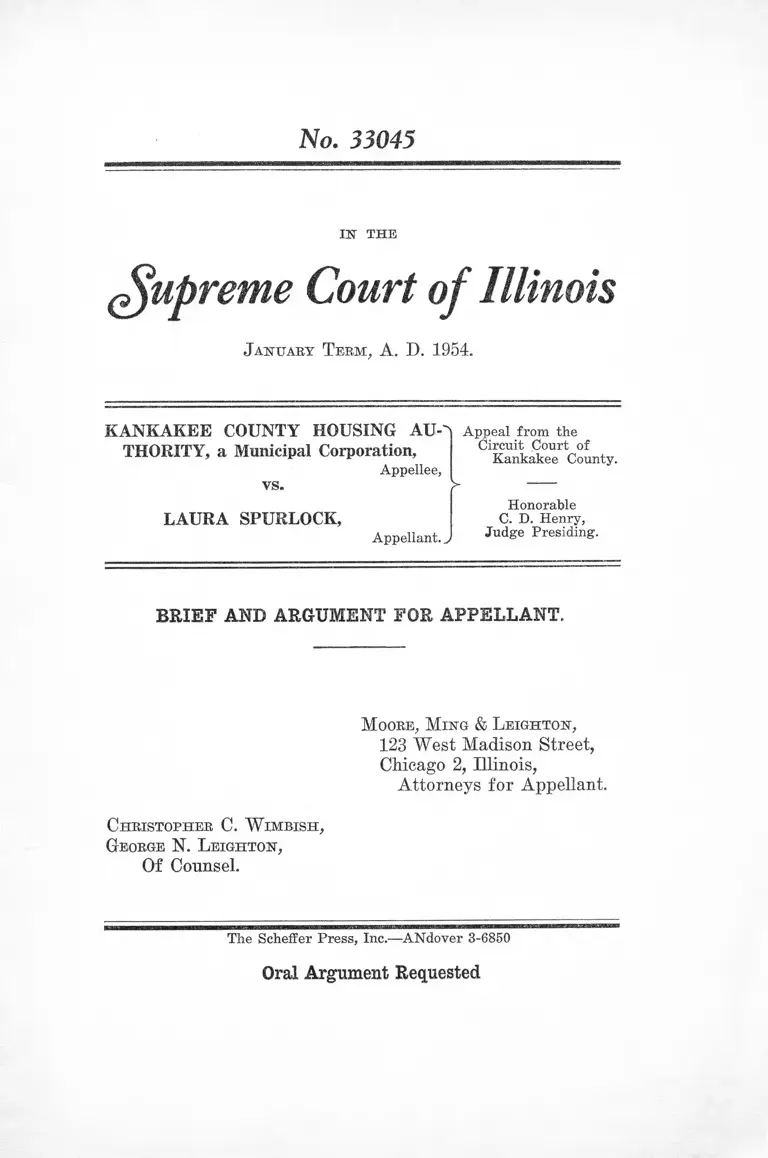

No. 33045

i n THE

Supreme Court of Illinois

J a n uary T e r m , A. D. 1954.

KANKAKEE COUNTY HOUSING AU-"j

THORITY, a Municipal Corporation,

Appellee,

Appeal from the

Circuit Court of

Kankakee County.

VS. >

LAURA SPURLOCK,

Appellant. ,,

Honorable

C. D. Henry,

Judge Presiding.

BRIEF AND ARGUMENT FOR APPELLANT.

M oore, M in g & L e ig h t o n ,

123 West Madison Street,

Chicago 2, Illinois,

Attorneys for Appellant.

C h r is t o p h e r C. W im b is h ,

G eorge N. L e ig h t o n ,

Of Counsel.

The Scheffer Press, Inc.—ANdover 3-6850

Oral Argument Requested

IN THE

S U P R E M E C O U R T OF I L L I N O I S

J a n uary T e r m ,, A. D. 1954.

KANKAKEE COUNTY H O U S I N G A Appeal from the

AUTHORITY, a Municipal Corpora- Circuit Court of

tio n , Kankakee County.

Appellee, L ------

VS. Honorable

LAURA SPURLOCK, C. D. Henry,

Appellant. _ Judge Presiding.

BRIEF AND ARGUMENT FOR APPELLANT.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.

Nature of the Action.

This is an Eminent Domain proceeding by which the

Appellee, Kankakee County Housing Authority, a Munic

ipal Corporation, invoked powers vested in it by Illinois

law, Chap. 67%, Sec. 9 and Ch. 47, Secs. 1-16, 111. Rev.

Stat. 1951.

Nature of the Pleadings.

The action was commenced by a Petition for Condemna

tion by which Appellee sought to acquire by eminent do

main land belonging to Appellant and 10 other owners

of real estate situated in Kankakee County (Abst. 1-14).

The petition to condemn contained 12 Counts and in it

petitioner alleged that by virtue of “ An Act in Relation

to Housing Authorities,” approved March 19, 1934, Chap.

67% 111. Rev. Stat. (1951) it is empowered to take for

public use the land described in the petition. Petitioner

alleged that it sought “ * * * to acquire said land herein-

after described for the purpose of constructing thereon a

housing project for public use which is a public work * * *”

(Abst. 1) The separate counts of the petition to condemn

realleged the same facts against the other parcels described.

Appellant and the other owners filed a motion captioned

“ Motion to Controvert the Petitioner’s Eight to Condemn

and to Strike and Dismiss the f’etition’ ’ (Abst. 14-32).

This motion to strike and dismiss was directed against

each count of the petition. Appellant and the owners by

their motion questioned the right of petitioner to con

demn the land in question and denied that the petitioner

had filed a petition sufficient in law in that the petitioner

had failed to set forth “ the purpose for which said prop

erty is sought to be taken or damaged” (Abst. 22). The

appellant and the owners put at issue the right of peti

tioner to condemn the land involved by alleging that the

petitioner was proceeding under supposed authority of the

laws of the State of Illinois and was seeking State judicial

action through the exercise of delegated eminent domain

powers to acquire appellant’s land in order to construct

thereon” * * * 40 housing units for a certain Ethnic Race

commonly known as “ Negroes” or colored people. Appel

lant and the land owners said that the housing project, for

which use petitioner intends to acquire the real estate

described in the petition, was not for use by the public,

but would be used by the Ethnic group commonly known

as ‘Negroes’ * * *” (Abst. 24-25).

Appellant, and the other owners, alleged in the motion

that the use to which petitioner was going to put the land

described in the petition was not a public use, because it

was to erect, establish and maintain a race segregated

housing project contrary to the public policy of the State

of Illinois and in direct violation of the laws of the State

of Illinois. Appellant then cited Chapter 38, Sec. 128(k),

111. Rev. Stat. (1951) and alleged that the use to which

appellant’s land would be put after condemnation by the

petitioner would be a direct violation of said statute. Ap

pellant in the motion then cited Article II, Sec. 2 of the

Constitution of the State of Illinois and cited, in haec verba,

Title 8, U.S.C.A., Sec. 41, Sec. 42 and Sec. 43, and Appel

lant further cited and relied upon the 14th Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States and put at issue

in said motion the constitutional validity of the acts of peti

tioner in the condemnation proceeding in attempting to

acquire land upon which would be constructed in the State

of Illinois a race segregated housing project (Abst. 24-25).

The motion to dismiss further alleged that in connection

with, and as a part of, the 40-unit public housing project

for Negroes to be built upon the land of appellant, and

the other 10 owners, the petitioner had acquired vacant

land upon which petitioner would construct 80 housing units

for white persons.

Appellant and the other 10 owners further alleged in

their motion that petitioner had submitted to the Public

Housing Administration of the Federal Government con

tract on application for an annual contribution under

which petitioner would attain allocation of federal funds

with which to build and maintain the race segregated pub

lic housing projects as announced and planned by peti

tioner, putting at issue the constitutional right of the

petitioner to invoke the judicial power of the State of

Illinois in accomplishing these agreements and purposes.

The Appellant and the other land owners asserted that

the acts and conduct of the petitioner as described and al

leged in the motion to dismiss were violative of the rights

of Appellant and the other land owners protected and

guaranteed by the due process clause of the 14th Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States and of the

— 3 —

— 4 —

federal statutes set forth in the motion, and were in viola

tion of the protection afforded to Appellant and the other

land owners by Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution

of the State of Illinois and in violation of the privileges

granted and the protection guaranteed by Chapter 38,

Section 128(k), 111. Rev. Stat. (1951).

Leading Facts.

The Court set the motion to dismiss for hearing. Evi

dence was introduced showing that the Appellee was or

ganized as a housing authority under the provisions of

Chapter 67%, 111. Rev. Stat. (1945). It conducted housing

surveys in Kankakee, Illinois, and determined that the

community needed a public housing project. The decision,

however, included the determination that the public hous

ing project was to consist of two separate installations:

one, consisting of 40 units, was to be occupied by Negroes

(Abst. 35, 36, 39) on land owned by Appellant, a Negro,

and the 10 other Negro owners of parcels in Hardebeck’s

Subdivision, Kankakee County (Abst. 34; See Ex. 216A-

216B in Petitioner’s Exhibit 10 and Defendant’s Exhibits

1 and 2, Abst. 39-43); the other, consisting of 80 units, was

to be occupied by white persons ( Abst. 34; See Ex. 216A

& 216B in Petitioner’s Exhibit 10 and Defendant’s Ex

hibits 1 and 2, Abst. 39-43). The project to be occupied

by white persons was to be constructed on vacant land

(Abst. 39-43). The project to be occupied by Negroes

was to be constructed on land subject of the condemna

tion petition (Abst. 39-43).

In the course of its proceedings and deliberations Ap

pellee administratively determined to exercise its delegated

powers of eminent domain as to the Appellant’s land and

the land belonging to the other 10 Negro owners of land

in Kankakee County and in Hardebeck’s Subdivision,

Thereafter Appellee made applications for an annual con

tributions contract under which it would receive federal

funds. The applications were made to the Chicago Office

of the Public Housing Administration under provisions of

Title III, 42 U.S.C., Sec. 14101 a) (Abst. 39-43). Approval

of the Chicago Field Office, Public Housing Administration,

was given on July 10, 1952. In its application to the fed

eral agency two separate files were “ tendered” contain

ing separate data for the white and non-white projects

(Abst. 39-43).

The motion to dismiss the petition to condemn Appel

lant’s land for use in constructing the project for Negroes

(Abst. 14-32) was then filed on the grounds already stated.

On May 22, 1953 the Court denied the motion to dismiss

stating that “ * * * the court having considered the evi

dence produced and the law applicable thereto, it is ordered

by the court that the motion to dismiss be and the same

is hereby denied and all objections overruled * * *” (Abst.

46).

The Court then ruled that a jury trial will be had on

Appellant’s parcel only, Count I of the petition to condemn

(Abst. 47). After the jury was selected, but before any

evidence was heard, Appellant filed a motion to discharge

the jury for the reason that it had come to her attention

that Negroes were excluded from the jury panel (Abst.

47-51). This motion was heard (Abst. 52). Testimony of

the following witnesses were introduced in evidence to sup

port the allegations of the motion:

Appellant testified that during the 28 years of residence

in Kankakee County she had never seen or heard of a

Negro serving on the jury (Abst. 52). Hlizabeth Luckey

testified that she had lived in Kankakee, Illinois since 1902

and during that time she learned that one Negro had been

— 5 —

— 6 —

called on the grand jury and two on the petit jury (Abst.

54). Rev. John T. Frazier testified that he had lived in

Kankakee, Illinois since January, 1950 and had been in

the County Court at least 12 times a year and in the Cir

cuit Court at least 6 times a year and he had never seen

a Negro on the jury (Abst. 54-55).

Orville Warren, Clerk of the County Court testified and

was shown defendants’ Exhibits 1 and 2 of June 30, 1953

purporting to be correspondence between him and the

Honorable Corneal Davis, a State Representative. The

letters, dated March 1, 1953 and April 30, 1953, concerned

a petition to the County Commissioners of Kankakee

County “ * * * protesting the fact that no Negroes are in

cluded in the jury call and requesting that they be asked

to serve on an equal basis with all persons in the County

of Kankakee * * *” (Abst. 55-56). Orville Warren ad

mitted having received the letter and the petition (Abst.

56) . These two letters were offered in evidence (Abst.

56-57) by Appellant. The court denied admission of the

letters, giving as its reason the fact that the jury panel

had been made in September of the previous year (Abst.

57) . The witness, Warren, then testified that in the six

years he had been Clerk of the County Court two Negroes

had served on the jury. This question was then asked the

witness: “ Q. Now, Mr. Warren in these juries that you

saw, these various panels that you personally saw, did

you see any members of the Negro race on these panels?

A. Well I don’t know, I don’t remember specifically.”

(Abst. 58-59)

Frank Burns testified that he had lived in Kankakee

County 63 years and had been a member of the bar in

Kankakee County since 1902 (Abst. 60). That there were

approximately 5000 Negroes in Kankakee County (Abst.

59). During that period of time he had never seen a

Negro on the jury (Abst. 59).

At the close of this evidence the court denied Appellant’s

motion to discharge the jury because Negroes were ex

cluded from the jury panel (Abst. 61). The court then

ordered that Appellant’s parcel of real estate be submitted

to a jury for trial (Abst. 61). The jury brought in its

verdict (Abst. 61) and the trial court entered judgment on

the verdict (Abst. 64). Appellant then filed her notice of

appeal, presented and filed the report of Proceedings and

perfected review in this Court (Abst. 62).

Decisions and Rulings.

1. The trial court denied the motion to controvert the

right to condemn and to strike and dismiss the petition

by its order of May 22, 1953 as follows:

“ * * * Now on this day this case having been under

advisement relevant to objections, motion, etc. and

the court having considered the evidence produced and

the law applicable thereto, it is ordered by the court

that the motion to dismiss be and the same is hereby

denied and all objections overruled * * (Abst. 46)

2. The trial court denied Appellant’s motion to dis

charge the jury because Negroes were excluded from the

jury panel (Abst. 47, 61).

The trial court denied admission in evidence of Appel

lant’s Exhibits 1 and 2 of 6/30/53 (Abst. 56-57).

The trial court denied Appellant’s motion for a new

trial (Abst. 64).

The trial court entered judgment in favor of Appellee

(Abst. 64).

Errors Relied Upon for Reversal,

1. The trial court erred in denying the motion to con

trovert petitioner’s right to condemn and to strike and

dismiss the petition.

2. The trial court erred in ruling that the petition to

condemn was sufficient in law.

-3. The trial court erred in sustaining the petition to

condemn appellant’s land after proof that the purpose for

which said land would be used was unlawful. The trial

court erred in denying the motion to dismiss and in pro

ceeding with the condemnation after all the evidence in

troduced showed that Appellee had abused the state dele

gated sovereign power of eminent domain and was in

voking state judicial action in a manner that deprived

Appellant of the rights secured by state and federal laws

and protected by state and federal constitutions.

4. The trial court erred in overruling the objections

of Appellant that the state court proceedings were state

action evoked by petitioner to effectuate a purpose that

deprived Appellant of rights protected by Article II,

Section 2 of the Constitution of the State of Illinois, and

secured and protected by the 14th Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

5. The trial court erred in inflicting upon Appellant

state court action, thus enabling petitioner to effectuate a

purpose violative of the State of Illinois and deprivation

of rights secured to Appellant by Article II, Section 2 of

the Constitution of the State of Illinois and the 14th

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

— 8 —

— 9 —

6. The trial court erred in granting relief to petitioner

in the condemnation proceeding thus invoking state action

that denied Appellant the equal protection of the laws as

secured and protected by the 14th Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

7. The trial court erred in denying Appellant’s motion

to discharge the jury because Negroes were excluded from

the jury panel, thus denying to Appellant due process of

law and the equal protection of the laws, as secured by

the 14th Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

8. The trial court erred in denying admission in evi

dence of Appellant’s Exhibits 1 and 2 of 6/30/53.

9. The trial court erred in overruling the motion for

a new trial and entering judgment in favor of Appellee.

— 10 —

PROPOSITIONS OF LAW AND AUTHORITIES.

I .

State delegated eminent domain powers do not authoirze

appellee to take appellant’s land by condemnation for

the construction of a race-segregated public housing

project, because the operation, maintenance and use of

public property, on the basis of race distinctions, will

violate Illinois laws.

Gillette v. Aurora By. Co., 228 111. 261.

Harvey v. Aurora <$> Geneva Ry. Co., 174 111. 295.

Bell v. Mattoon Water Works Co., 245 111. 544.

Bierbaum v. Smith, 317 111. 147.

Pickett v. Kuchan, 323 111. 138.

White v. Pasfield, 212 111. App. 73.

Baylies v. Curry, 128 111. 287.

Chicago <& N. W. Ry. Co. v. Williams, 55 111. 185.

Chase v. Stephenson, 71 111. 383.

People ex rel. Longress v. Board of Education of

the City of Quincy, 101 111. 308.

People ex rel. Bibb v. City of Alton, 193 111. 309.

Peck v. Cooper, 112 111. 192.

Dean v. Chicago <& N. W. Ry. Co., 183 111. App. 317.

Denny v. Dorr, 333 111. App. 581.

People ex rel. Touhy v. City of Chicago, et al., 394

111. 471.

II.

Even if the use of eminent domain powers by appellee to

acquire appellant’s land for a race-segregated public

housing project is authorized by Illinois law, the exer

cise of such power, and the judgment of the trial court

are State actions which deprived appellant of her prop

erty without due process of law and denied appellant

equal protection of the laws, in violation of rights se

cured to appellant by the 14th Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States.

Department of Public Works & Buildings v. Kirk-

endall,...... Ill......... , 112 N. E. 2d 611.

— 11 —

Department of Public Works & Buildings v. Chi

cago Title $ Trust Company, et al., 408 111. 41.

Chicago, B. <& Q. B. Co. v. City of Chicago, 116

U. S. 226, 17 S. Ct. 581.

Gillette v. Aurora By. Co., 228 111. 261.

Board of Education v. City of Chicago, 402 111. 291.

Missouri Pacific By. Co. v. State of Nebraska, 164

U. S. 403, 17 S. Ct. 130:

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 68 8. Ct. 836.

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 38 S. Ct. 16.

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668, 47 S. Ct. 471.

Bichmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704, 50 S. Ct. 407.

III.

Exclusion of members of the negro race from the jury

panel, as shown in this case, was a denial of equal pro

tection of the laws in violation of appellant’s rights under

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution.

Brown v. Allen, 344 II. S. 443, 73 S. Ct. 397.

Avery v. State of Georgia, 345 U. S. 559, 73 S. Ct.

891.

— 12 —

ARGUMENT,

I .

State delegated eminent domain powers do not authorize

appellee to take appellant’s land by condemnation for

the construction of a race-segregated public housing

project, because the operation, maintenance and use of

public property, on the basis of race distinctions, will

violate Illinois laws.

Illinois law of Eminent Domain rests on two funda

mental constitutional conditions: First, that the nse to

which private property is to be devoted shall be a public

one; the second, that just compensation shall be made to

the owner for the property taken. Gillette v. Aurora Ry-

Co., 228 111. 261, 275. In this case, no question is raised

concerning the constitutional requirement of just compen

sation. The controversy revolves around the use which

Appellee, Kankakee County Housing Authority, intends

for the land taken from Appellant by these condemnation

proceedings.

The Appellee in its petition for condemnation (Abst. 1-

14) alleged that “* * # by virtue of ‘An Act in Relation

to Housing Authorities’ * * * it is empowered to take for

public use (sic) condemnation proceedings, without the

consent of the owners, the land * * described in the

petition and belonging to Appellant. The statute upon

which Appellee depends for its authority to condemn Ap

pellant’s land is Chapter 67%, 111. Rev. Stat. 1951. Ref

erence to that statute shows that Section 8 confers upon

Appellee, a housing authority, powers to investigate hous

ing needs in the area of its operation and to cooperate with

the regional or State planning agency within its area of

— 13 -

operation. That section empowers Appellee to operate

projects and to construct, reconstruct, improve, alter or

repair projects and act as agent of the Federal Govern

ment in the construction or management of a project.

Appellee is to function in accordance with the section as

an agency of the city, village or town or act as an agent

of the government relating to housing and the purposes

of the Act. Appellee has power under the Act to lease

or rent housing or other accommodations and to acquire

interest in any firm, corporation or instrumentality of

the State or Federal government. The Act makes Appellee

“ * # * a municipal corporation and shall constitute a body

both corporate and politic exercising a public and essen

tial governmental function * * *” Section 9 of the Act

authorized Appellee to acquire property, and if necessary

by exercise of Eminent Domain in accordance with the

Eminent Domain Act, Chapter 47, Secs. 1-16, 111. Rev. Stat.

1951. That section further provides that the Appellee

submit to the State housing board and obtain its approval

of plans for the development and redevelopment of ac

quired property. Appellee, as a housing authority, is

authorized to hold or use property acquired by it for uses

authorized by the Act. Section 14 of the Act provides for

approval of the State Housing Board for the projects prior

to the acquisition of title by Appellee to any real prop

erty.

The record before this Court presents little controversy

about the facts. Mr. Armen R. Blanke, Chairman of the

Kankakee County Housing Authority, though somewhat

evasive on cross-examination, finally admitted that the use

for which Appellant’s land was being taken was to build

two separate projects, one of 80 units to be occupied by

white people; the other of 40 units to be occupied by

Negroes (Abst. 35, 36, 39). In its application for federal

aid under the Act, Appellee submitted two separate de

— 14 —

velopment programs. These are defendant’s Exhibits 1

and 2 introduced in evidence on May 6, 1953 (Abst. 39-43).

Defendant’s Exhibit 1 reveals that Appellee proposes to

construct on the land being taken from Appellant the

project for Negro occupancy. Throughout this Exhibit

are interspersed references to race and race distinction

uses to which the 40 unit project would be put. The con

clusion is inescapable that Appellee has administratively

determined that Appellant’s land is to be used for the

construction of a project devoted to race segregation.

This conclusion is supported by defendant’s Exhibit 2,

introduced in evidence on May 6, 1953 showing that Appel

lee proposes to use vacant land for the construction of the

80-unit project for occupancy by white persons who will

be segregated from the Negroes housed in the 40 unit

project (Abst. 42).

Appellant’s motion to dismiss the petition put in issue

the validity of the condemnation proceeding by which

Appellant’s land was being subjected to Eminent Domain

proceedings for a race segregatory and race discrimina

tory use. Our Eminent Domain laws have evolved certain

clear-cut principles which we submit are controlling in this

ease. First, Appellee when it “ * * * seeks to exercise the

power it must be able to point to a statute conferring it

in express terms # * *” Gillette v. Aurora By. Co., 228

111. 261, at 275. This Court has had occasion to say

“ * * * The taking of private property against the will of

the owner is in derogation of the property rights of the

citizen, and the authority must not only be conferred by

statute in express language, but the use for which the

property is taken must be clearly within the object desig

nated by the statute. The statute must be strictly con

strued in favor of the property owner and doubts must

be solved adversely to the claim of right to exercise the

power. Unless both, the letter and the spirit of the statute

confer the power it cannot be exercised, and if the words

of the grant are doubtful they are to be taken most strongly

against the grantee * # *” Gillette v, Aurora By. Co., 228

111. 261, at 275. Harvey v. Aurora <& Geneva By. Co., 174

111. 295, at 305.

Abuse of the right of Eminent Domain will be prevented

by a court upon proper showing. Bell v. Mattoon Water

Works Co., 245 111. 544, at 547. While it is true “ * * *The

question under what conditions the power of eminent do

main may be exercised is purely legislative, but it is for

the court to decide, as a preliminary question, when called

upon, whether the statutory conditions authorizing the

exercise of such power exist, and if such statutory condi

tions are not found to exist in the specific case, to dis

miss the petition for condemnation * * *” Bierbaum v.

Smith, 317 111. 147, at 149.

Nothing beyond the allegations of the petition was pre

sented by Appellee to sustain its claim;—that it had the

right to exercise Eminent Domain and acquire Appellant’s

land (Abst. 1-2). Nothing in the statute authorizing

Appellee to exercise the powers of Eminent Domain ex

pressly or impliedly grants to Appellee the power to take

Appellant’s land for a race segregated housing project.

We submit, therefore, that the absence of express or im

plied powers to take Appellant’s land for a race segre

gated public housing project is fatal to the condemnation

proceeding in this case. This issue was precisely raised

by Appellant in the motion to dismiss (Abst. 14). The

evidence in this record and the legal basis for the conten

tion sustain the position of Appellant.

There is a clear reason why the statute creating Appel

lee does not authorize it to acquire land and property to be

— 15 —

16 —

used on the basis of race distinctions. That reason is found

in the statutes of this State that expressly prohibit race

segregation and race discrimination in all the relationships

upon which legislative action has been taken. Our re

search has led us to 14 different and distinct statutory

provisions of this State, all expressly condemning, and

specifically prohibiting race segregation and race discrim

ination. We list them in this order:

1. Chapter 14, Section 9, 111. Eev. Stat. 1951, creating

a division for enforcement of Civil Eights.

2. Chapter 29, Sections 24a-24g, prohibiting race segre

gation and race discrimination in employment under public

contracts.

3. Chapter 43, Section 133, prohibiting race segregation

and race discrimination in taverns.

4. Chapter 23, Section 46, prohibiting race segregation

and race discrimination in public assistance.

5. Chapter 32, Section 510(9) prohibiting race segre

gation and race discrimination in employment by housing

corporations.

6. Chapter 48%, Section 36(3) prohibiting race segre

gation and race discrimination in private engineering

schools.

7. Chapter 38, Sections 125-128n, prohibiting race seg

regation and race discriminations in inns, restaurants, eat

ing houses, hotels, soda fountains, saloons, barber shops,

bath rooms, theaters, skating rinks, concerts, cafes, bicycle

rinks, elevators, ice cream, parlors or rooms, railroads,

omnibuses, stages, streetcars, boats, funeral hearses and

public conveyances on land and water, and all other places

of public accommodation and amusement.

17 —

8. Chapter 38, Section 128k, prohibiting denial or re

fusal to any person on account of race, color or religion

equal enjoyment of public property.

9. Chapter 38, Section 471 prohibiting anti-race ex

hibitions.

10. Chapter 32, Section 503a, prohibiting race segre

gation and race discrimination in world-fair concessions.

11. Chapter 105, Section 168.1, prohibiting race segre

gation and race discrimination in state parks.

12. Chapter 122 Sections 6-37, 18-14, prohibiting race

segregation and race discrimination in public schools.

13. Chapter 127, Section 214, establishing a Human

Relations Commission.

14. Chapter 127, Section 60, prohibiting race segre

gation and race discrimination in private schools.

These enumerated statutes have been construed by this

court on numerous occasions. They have been held to be

constitutional and valid. Pickett v. Kuchan, 323 111. 138.

Our courts of review have sustained the right of recovery

for violation of the protections conferred and guaranteed

by these statutes. White v. Pas field, 212 111. App. 73;

Baylies v. Curry, 128 111. 287; Chicago d N.W. By. Co. v.

Williams, 55 111. 185; Chase v. Stevenson, 71 111. 383; People

ex rel. Congress v. Board of Education of the City of

Quincy, 101 111. 308; People ex rel. Bibb v. City of Alton,

193 111. 309; Peck v. Cooper, 112 111. 192; Dean v. Chicago &

N.W. By. Co., 183 111. App. 317; Denny v. Dorr, 333 111. App.

581.

The vice of Appellee’s position need not be exposed only

by reference to the race discriminatory use to which Appel

lee will put the land condemned. For the purpose of the in

18

slant ease we consider Appellant’s contention legally un

assailable when wTe point out that as a matter of law the use

for which Appellant’s property is being condemned is not a

public use. It is easily observed that the property will not

be used for the public but rather for a class within a class;

that is, Negro persons who will qualify for low rent housing

in the public housing project for colored occupancy as

planned by Appellee. Thus, not only is the public in gen

eral excluded from the use intended for Appellant’s prop

erty, but even within the class restricted there is the fur

ther limitation that only those Negroes who qualify for low

rent housing will be allowed to use the public housing

project being constructed for Negro occupancy.

These facts being indisputable, they necessarily repre

sent the question whether the use to which Appellant’s

land will be put by Appellee is a public use as required by

our Constitution. This court said in People ex rel. Touhy

v. City of Chicago, et al, 394 111. 471 at 483-484: “ * * * In

Bartee Tie Co. v. Jackson, 281 111. 452, in discussing this

question, we said that to constitute a public use the use

must concern the public as distinguished from an in

dividual or a particular number of individuals. Public

use requires that all persons must have an equal right to

the use and that it must be in common upon the same terms,

however few the number who avail themselves of i t ; that

it shall be open to all people to the extent that its capacity

may admit of such use. Such use cannot be confined to

privileged persons and must be for all men or a class of

men, and not for a special few * * * ”

This doctrine is decisive of the question raised by

Appellant. We respectfully submit that Appellee has no

eminent domain powers to condemn Appellant’s land for

a race segregated housing project. The authority to take

private property for a race segregated public housing

— 19 —

project cannot be implied because it will be a wide depar

ture from well established public policy of this State.

Clearly, the use to which Appellant’s land is to be put by

Appellee is not a public one. It is a use to be limited to a

class of low income earners, within a class determined by

race. There is no authority in Illinois Eminent Domain

Law for such taking of Appellant’s land.

II.

Even if the use of eminent domain powers by appellee to

acquire appellant’s land for a race-segregated public

housing project is authorized by Illinois law, the exer

cise of such power, and the judgment of the trial court

are state action which deprived appellant of her prop

erty without due process of law and denied appellant

equal protection of the laws, in violation of rights se

cured to appellant by the 14th Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States.

In filing the petition to condemn Appellant’s land (Abst.

1-14) Appellee exercised a delegated right of the sovereign

State of Illinois. Department of Public Works d Build

ings v. Kirkendall, ...... Ill......... , 112 N. E. 2d 611; De

partment of Public Works d Buildings v. Chicago Title

d Trust Company, et al., 408 111. 41. Actions of the Ap

pellee and the rulings and judgment of the trial court are

State acts within the meaning of the 14th Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States. “ * * * it must be

observed that the prohibitions of the (14th) amendment

refer to all the instrumentalities of the state,—to its

legislative, executive, and judicial authorities,—and there

fore whoever, by virtue of public position under a state

government, deprives another of any right protected by

that amendment against deprivation by the state, ‘violates

the constitutional inhibition; and as he acts in the name

and for the state, and is clothed with the state’s power,

— 20

his act is that of the state’ * * *” Chicago, B. £ Q. R. Co.

v. City of Chicago, 166 U. S. 226, at 234, 17 S. Ct. 581, at

583. In overruling Appellant’s motion to dismiss and

entering judgment against Appellant, the trial court ruled

adversely to all the federal and state constitutional rights

asserted. Chicago, B. d Q. R. Co. v. City of Chicago, 166

TJ. S. 226, 17 S. Ct. 581.

The principal ground of constitutional protection ad

vanced by Appellant in the trial court was that the Kan

kakee County Housing Authority, Appellee, was exercis

ing state power granted to it by Ch. 67%, 111. Rev. Stat.

1951, and in so doing it was proceeding with condemna

tion against Appellant and others, for the purpose of

taking her land on which to build a public housing project

for Negroes (Abst. 17-25). Appellant further asserted that

the acts of Appellee under color of state law were arbi

trary, capricious and discriminatory in that the acts of

Appellee were based on decisions to proceed against her,

a Negro, and to condemn her land on which to build a

public housing project for Negroes. At the same time,

however, Appellee had purchased vacant land on which

to build a public housing project for white persons Abst.

21-22). Thus, Appellant asserted two serious federal con

stitutional objections to the condemnation proceeding:

first, that the taking of Appellant’s land was not for a

public purpose; second, that the state action was directed

against her solely because of race distinctions. We turn

now to the first constitutional objection.

The right of eminent domain is inherent in the sov

ereign; but its exercise is subject to two constitutional

conditions which we have already pointed to : first, the

taking of private property under eminent domain powers

must be for a public purpose; second, just compensation

must be paid for the land taken. Gillette v. Aurora Ry.

21

Co., 228 111. 261, 275. We make no assault upon the award

as contravening the constitutional requirement of just

compensation—not because we deem it in conformance

with the constitutional condition, but because we consider

the infirmities of these proceedings such that the question

need not be reached.

Appellee’s petition to condemn (Abst. 1-14) alleged only

that # # Petitioner seeks to acquire said land herein

after described for the purpose of constructing thereon

a housing project for public use and which is a public

work * * *” (Abst. 2). Appellant had the right to con

test petitioner’s right to condemn, and she did so by

motion to dismiss; and having done so, the burden was

on Appellee to maintain its right by proper proof. Board

of Education v. City of Chicago, 402 111. 291. “ * # * If the

land owner traverses the allegations of the petition neces

sary to confer jurisdiction, the court must determine their

truth or falsity. The necessity will therefore exist for the

petitioner to introduce such evidence as will, prima facie,

at least, prove the traversed or disputed allegations of the

petition * * *” Board of Education v. City of Chicago,

402 111. 291, at 299.

Evidence introduced by Appellee itself showed that Ap

pellant’s land was being taken for the construction of a

public housing project for Negro occupancy (Abst. 33-39).

The testimony of the only witness for Appellee proved

that one of the factors considered by Appellee -was the

concentration of Negro residences in the area where Ap

pellant’s land was situated (Abst. 35). Appellee’s pur

pose was to preserve the racial residential segregation

pattern by the device of building the Negro housing

project on Appellant’s land (Abst. 36). Evidence then

introduced by Appellant removes all conjecture as to the

purpose to which Appellant’s land will be put. Three ex-

22 —

Mbits (Abst. 33-34; 39-43) clearly show the race segregatory

objectives of Appellee. They also show the discrimination

exercised by Appellee in proceeding against Appellant

solely because she was a Negro who owned land in an

area into which Appellee decided to restrict Appellant and

others of the Negro race (Abst, 35-36). The conclusion is

inescapable that the purpose for which Appellant’s land

was to be taken was not a public purpose.

It was not a public purpose because the use was to be

restricted to a racial segment of the people. In Illinois,

the public, as a political and social concept includes every

body. To exclude everybody and devote property to a

use limited to a racial segment—Negroes—, is to exclude

the public, as we understand that word. In this sovereign

State we can glance retrospectively into its history and

with gratification say that racial dichotomies and racial

classifications have never been accepted as a basis for

grant or denial of public privileges. Yet, this is precisely

the result for which Appellee sought Appellant’s land.

The condemnation proceeding to take Appellant’s land

for a use not public, denies Appellant due process. In

Missouri Pacific Ry. Co. v. State of Nebraska, 164 U. S.

403, at 412, 17 S. Ct. 130, at 133, for example, a railroad

company by mandamus, was directed within a stated time,

to surrender a portion of its right of way for an elevator

to be used by a group of farmers and others who had

alleged they lacked elevator services which had been fur

nished to others. The Supreme Court of the United States

speaking by Mr. Justice G-ray, said: “ * * * The taking

by a state of private property of one person or corpora

tion, without the owner’s consent, for the private use of

another, is not due process of law, and is a violation of

the fourteenth article of amendment of the constitution of

the United States * # *” In Chicago, B. & Q. R. Co. v.

23 —

City of Chicago, 166 U. S. 226, at 241,17 S. Ct. 581, at 586,

Mr. Justice Harlan speaking for the Court and citing

Cooley’s Edition of Story on Constitutional Limitations,

said:

“ * * * ‘Due process of law requires—First, the leg

islative act authorizing the appropriation, pointing

out how it may be made and how the compensation

shall be assessed; and, second, that the parties or of

ficers proceeding to make the appropriation shall

keep within the authority conferred, and observe every

regulation which the act makes for the protection or

in the interest of the property owner, except as he

may see fit voluntarily to waive them * * *”

Taking Appellant’s land for what is in effect private

use is not the only vice attendant upon the condemnation

here involved. What the evidence indisputably shows is

this:

Appellee, an agency of the State of Illinois (Abst. 1)

made an administrative determination that Appellant’s

land, and the land of other Negro owners not here on ap

peal, would be condemned because it was desirable to

build a public housing project for Negroes in the area

where Appellant’s land was situated and already occu

pied by Negroes (Abst. 35-36). As part of this deter

mination, Appellee decided that it will construct an

80 unit housing project for white persons on vacant land

(Abst. 39-43). Defendant’s Exhibit 2 (Abst. 39-43) con

tains an exhibit numbered 216B. This exhibit is an aerial

photograph showing the vast expanse of the vacant land

on which Appellee will construct the 80 unit project for

White persons (Abst. 43). Thus, it will easily be seen

that the only reason why Appellee elected to proceed with

condemnation against Appellant is because of the racial

characteristics of Appellant and the other land o'wners

involved (Abst. 35-36). The aerial photograph of the vacant

- 24 -

land is paralleled by an aerial photograph in Defendant’s

Exhibit 1 (Abst. 39-43) showing Appellant’s occupied land.

These photographs speak silently but eloquently of the

inherent discrimination and unfairness resting beneath

Appellee’s administrative determinations.

We are constrained to say respectfully to this Honorable

Court that race discriminations take many and sometimes

subtle forms. The case at bar presents race discrimina

tion in a form not easily detected. Under the guise of

building a public housing project for 40 Negro families,

Appellee is imposing discriminatory state action against

Appellant. The public policy of this State when applied

by this Honorable Court, we think will furnish adequate

statutory and constitutional grounds for a reversal; but

transcending State constitutional protections is the broad

sweep of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

As a predicate for demonstrating the applicability of

protection under the 14th Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, we refer to the record before the

Court. Pointing again to Defendant’s Exhibits 1 and

2 (Abst. 39-43) we call attention to the fact that Ap

pellee instituted these condemnation proceedings in order

to perform its part of an “ Annual Contributions Con

tract” (Abst. 39-43), 42 U. S. C. A. Sec. 1410, with the

Public Housing Administration, a federal agency. Under

the provisions of Ch. 67%, 111. Rev. Stat. 1951, and 42

U. S. C. A. Secs. 1401-1430, Appellee, as a State agency

was under the duty to enter into contracts with the federal

agency and with the City of Kankakee dealing with the

construction, maintenance and operation of the racially

segregated public housing projects. Attention is called

again to Defendant’s Exhibit 1 (Abst. 39) which con

tains a letter of transmittal from the Director of the

— 25

Chicago Field Office, Public Housing Administration ask

ing Appellee to proceed with condemnation of Appellant’s

land in accordance with the then approved annual con

tributions contract with the federal agency (Abst. 39).

Condemnation of Appellant’s land, then, was not an

isolated act of Appellee; it was part of a series of inter

related agreements, covenants and undertakings which

could be carried out only with the assistance of the Cir

cuit Court of Kankakee County. It is clear, that but for

the intervention of the state court, acting as it did on

determinations of Appellee based on race, Appellant would

be free to continue her enjoyment of her property without

restraint and interference by Appellee. This interference,

“* * * supported by the full panoply of state power * * *”

is what the Supreme Court of the United States in The

Restrictive Covenant Cases said cannot be invoked without

violation of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States. We re

spectfully submit that careful study of the doctrine of

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 68 S. Ct. 836, 3 ALR

2d 441 will reveal that it determines the issues at bar.

In Shelley v. Kraemer, one of the Covenant cases, thirty

out of a total of thirty-nine owners of property in the

city of St, Louis, Missouri signed a restrictive covenant

to prevent occupancy of the affected realty to people of

the Negro or Mongolian Race. The petitioners who were

Negroes, purchased for a valuable consideration one of

the parcels of real estate covered by the covenant. There

after, in a suit brought by other signers of the covenant,

the Supreme Court of Missouri held that the White prop

erty owners were entitled to injunctive relief restraining

Shelley from occupying his property, and to a decree di

vesting title from him. On certiorari, Shelley contended

that judicial enforcement of the restrictive agreements

violated rights guaranteed him by the Fourteenth Amend

— 26 —

ment to tlie Federal Constitution and Acts of Congress

passed pursuant to the Amendment. Specifically, Shelley

urged that he had been denied equal protection of the

laws, deprived of property without due process of law,

and was denied privileges and immunities of a citizen of

the United States. Mr. Chief Justice Yinson, speaking for

the Court, said: 334 U. S. 1, at 14, 68 S. Ct. 836, at 842:

“ * * * That the action of state courts and of judicial

officers in their official capacities is to be regarded as

action of the State within the meaning of the Four

teenth Amendment, is a proposition which has long

been established by decisions of this Court. That prin

ciple was given expression in the earliest cases in

volving the construction of the terms of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Thus, in Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S.

313, 318 (1880), this Court stated: ‘It is doubtless

true that a State may act through different agencies,—

either by its legislative, its executive, or its judicial

authorities; and the prohibitions of the amendment

extend to all action of the State denying equal protec

tion of the laws, whether it be action by one of these

agencies or by another.’ In Ex parte Virginia, 100

U. S. 339, 347 (1880), the Court observed: ‘A State

acts by its legislative, its executive, or its judicial

authorities. It can act in no way.’ In the Civil Rights

Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 11, 17 (1883), this Court pointed

out that the Amendment makes void ‘State action of

every kind” which is inconsistent with the guaranties

therein contained, and extends to manifestations of

“ State authority in the shape of laws, customs, or

judicial or executive proceedings.’ Language to like

effect is employed no less than eighteen times during

the course of that opinion * * *”

“ We have no doubt that there has been state action

in these cases in the full and complete sense of the

phrase. The undisputed facts disclose that petitioners

were willing purchasers of properties upon which they

desired to establish homes. The owners of the prop

27 —

erties were willing sellers; and contracts of sale were

accordingly consummated. It is clear that but for the

active intervention of the state courts, supported by

the full panoply of state power, petitioners would have

been free to occupy the properties in question without

restraint * * *” 334 U. S. 1 at 19, 68 S. Ct. 836 at 845.

“ We hold that in granting judicial enforcement of

the restrictive agreements in these cases, the States

have denied petitioners the equal protection of the laws

and that, therefore, the action of the state courts can

not stand. We have noted that freedom from dis

crimination by the States in the enjoyment of property

rights was among the basic objectives sought to be

effectuated by the framers of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. That such discrimination has occurred in these

cases is clear. Because of the race or color of these

petitioners they have been denied rights of ownership

or occupancy enjoyed as a matter of course by other

citizens of different race or color. The Fourteenth

Amendment declares ‘that all persons, whether col

ored or white, shall stand equal before the laws of

the States, and, in regard to the colored race, for

whose protection the amendment was primarily de

signed, that no discrimination shall be made against

them by law because of their color.’ ” 334 U. S. 1, at

20-21, 68 S. Ct. 836, at 845-846.

In language which we respectfully submit expresses the

position of Appellant at bar, Mr. Chief Justice Vinson

said:

“* * * The historical context in which the Fourteenth

Amendment became a part of the Constitution should

not be forgotten. Whatever else the framers sought

to achieve, it is clear that the matter of primary con

cern was the establishment of equality in the enjoy-

men of basic civil and political rights and the preser

vation of those rights from discriminatory action on

the part of the States based on considerations of race

or color. Seventy-five years ago this Court announced

that the provisions of the Amendment are to be con

— 28

strued with this fundamental purpose in mind. Upon

full consideration, we have concluded that in these

cases the States have acted to deny petitioners the

equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment * * * ” 334 U. S. 1, at 23, 68 S. Ct.

836, at 847.

Shelley v. Kraemer and the case at bar present applicable

similarities at three important points: first, a race segre-

gatory pattern is involved in the case at bar as was sought

enforcement in Shelley; second, aid of the state through

its judicial arm was sought and effectively invoked so that

the action against Appellant was “ * * * supported by the

full panoply of state power, * * *” as it was against

Shelley; finally, the oppressive action of the State insti

tuted by Appellee against Appellant was based on deter

minations and distinctions of race and color as was the

state action against Shelley. We respectfully submit that

the broad scope of the 14th Amendment to the Federal

Constitution will not allow such oppressive State action.

Finally, concluding our argument on the constitutional

questions, we point to the fact that Appellee seeks to ac

complish by this condemnation proceeding a result which

the Supreme Court of the United States has consistently

said neither the City of Kankakee nor the State of Illinois

could achieve even by the exercise of police powers. If

Appellee were allowed to take Appellant’s land and con

tract a race segregated public housing project, it must

be assumed that it will carry out its purpose once such a

segregated project is built. Appellee then could admin

istratively enforce race segregation in its area of opera

tion. The City of Kankakee could not adopt an ordinance

and enforce race segregation within its limits. This was

the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in

Buchanan v. Worley, 245 U. S. 60, 38 S. Ct. 16, where the

City of Louisville, Kentucky adopted a municipal ordi

29 —

nance prohibiting any white or colored person from mov

ing into and occupying as a residence or place of abode

any house upon any block where a greater number of

houses are occupied by persons of the opposite race. Bu

chanan, a white man, accepted an offer from Warley, a

colored man, by which Warley was to purchase Buchanan’s

lot. Afterward, Warley, depending upon the municipal

ordinance, refused to comply with the contract. Buchanan

then filed a suit for specific performance which was denied

on the ground that Warley could not occupy the property

which Buchanan attempted to sell to him. On writ of

error from the Supreme Court of the United States, after

affirmance in the highest court of the state, it was held,

that though Buchanan was a white man, he could raise

the constitutional question concerning the validity of the

municipal ordinance under the 14th Amendment. The

“ * * * We think this attempt td prevent the alienation

of the property in question to a person of color was

not a legitimate exercise of the police power of the

state, and is in direct violation of the fundamental law

enacted in the Fourteenth Amendment of the Consti

tution preventing state interference with property

rights except by due process of law * * *” Buchanan v.

Warley, 245 U. S. 60, at 66, 38 S. Ct. 16, at 20.

The doctrine of Buchanan v. Warley has particular ap

plication here because Buchanan, a white man was held

to be in position to attack the constitutionality of a mu

nicipal ordinance aimed at the segregation of Negroes. The

court held that because Buchanan’s property rights were

adversely affected by the ordinance, he could successfully

make attacks upon its constitutionality.

Now applying that doctrine to the case at bar, we submit

that Appellant, because her property is affected adversely

by an administrative determination of Appellant, a munic

— 30 —

ipal corporation, can put in issue the constitutionality of

that administrative determination as if it were an ordi

nance adopted by the City of Kankakee. In either case,

whether it be an Ordinance of the City of Kankakee, or

an administrative rule of Appellee, under the Buchanan

case, she could successfully attack the unconstitutionality of

such state action on her property rights. Harmon v. Tyler,

273 U. S. 668, 47 S. Ct. 471; Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S.

704, 50 S. Ct. 407; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 68 S. Ct.

836.

Therefore, either on the ground that the condemnation

proceedings denied Appellant due process of law because

the taking of her land was not for a public use, or because

the action against her was State action that denied her

equal protection of the laws in violation of the 14th Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States, we submit

that the record at bar shows that the rulings and judgment

of the trial court cannot be sustained because they violate

and contravene basic constitutional guarantees.

III.

Exclusion of members of the negro race from the jury

panel, as shown in this case, was a denial of equal pro

tection of the laws in violation of appellant’s rights under

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution.

The gamut of a jury trial is not without its unpleasant

experiences. In this case Appellant, after the jury was

selected, but before any evidence was heard, made a mo

tion to discharge the jury for the reason that members of

the Negro race were excluded from the jury panel (Abst.

48-51). A hearing on this motion was granted by the trial

court (Abst. 52). At this hearing Appellant introduced

in evidence the testimony of four witnesses in addition to

her own testimony. No evidence contradicting the testi

— 31 —

mony or evidence thus presented was produced by Appel

lee.

Appellant and two other witnesses testified that it was

a well known fact in Kankakee County that Negroes could

not serve on petit juries (Abst. 52). Orville Warren the

Clerk of the County Court testified and admitted having

received a letter from a State Representative presenting

a Petition signed by Negro residents of Kankakee County

asking the County Commissioners to call Negroes to serve

on juries on an equal basis with other citizens (Abst. 56).

Two exhibits consisting of letters concerning this petition

were offered in evidence and refused by the trial court

(Abst. 56-57). One witness, an attorney, testified that he

had been a member of the Bar in Kankakee County since

1902 and he had practiced law during that time in the

county and had seen more than 300 juries, but had never

seen a Negro on the jury in the County. This witness

testified that there were approximately 5000 Negroes in

Kankakee County (Abst. 59). Appellant in her motion,

supported by affidavit, alleged that there were approx

imately 2490 Negroes in the County. None of these allega

tions, nor any of the evidence thus introduced by Appel

lant, was either contradicted or refuted. The court denied

the Motion (Abst. 60-61).

We submit that Appellant, within the time allowed by

the circumstances shown in the record, made a prima facie

showing of discrimination in the selection of the jury that

was to hear her case. In Brown v. Allen, 344 TJ. S. 443,

at 470-471, 73 S. Ct. 397, at 414, in an opinion by Mr.

Justice Reed, the Supreme Court of the United States

said:

“ * * * Discrimination against a race by barring or

limiting citizens of that race from participation in

jury service are odious to our thought and our Consti

tution, This has long been accepted as the law * * *”

32 —

* * * Such discrimination is forbidden by statute 18

U. S. C. Sec. 243, 18 U. S. C. A. Sec. 243, and bas been

treated as a denial of equal protection under tbe Four

teenth Amendment to an accused, of the race against

which the discrimination is directed * * *”

In Avery v. State of Georgia, 345 U. S. 559, 73 S. Ct.

891 the Supreme Court of the United States, in an opinion

by Mr. Chief Justice Vinson, held that where defendant

challenged the selection of the jury and charged that mem

bers of his race had been discriminated against in the

composition of the jury, and a prima facie case was made,

a burden was put on the state to overcome such prima facie

case. In the case at bar we respectfully urge this Honor

able Court to consider the evidence introduced by Appel

lant in view of the failure of Appellee to refute or contra

dict any allegation or any of that evidence. The proof made

raised a serious federal constitutional question concerning

the fairness of the trial afforded Appellant. The two ex

hibits offered in evidence by Appellant (Abst. 56) spoke

louder than the testimony that supported the allegations

made. It is very difficult to understand the reasoning of

the trial court, but it appears that the learned judge ruled

that because the jury panel was compiled in September, Ap

pellant could not complain in June that there had been ex

clusion of Negroes from the panel. It is obvious that Appel

lant and the other Negroes in the county had no part in

the forming of the jury panel whether it was constituted in

September or in June. As Mr. Justice Frankfurter said in

the Avery Case, “ * * * However that may be, * * * the

stark resulting phenomenon here was that some how or

other, * * *” no Negro got onto the panel of jurors from

which Appellant’s jury was selected. Avery v. State of

Georgia, 345 U. S. 559, at 564, 73 S. Ct. 891, at 894. The

only rational explanation for the consistent absence of

Negroes from juries in Kankakee County as testified to by

— 33

Appellant (Abst. 52), Mrs. Elizabeth Luckey (Abst. 53-54)

Rev. John T. Frazer (Abst. 55-56), Mr. Orville Warren

.(Abst. 56-59), and Mr. Frank Burns (Abst. 59) is that they

were systematically excluded. This exclusion denied Ap

pellant the guarantees afforded by the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States.

CONCLUSION.

From the foregoing Argument, supported by the author

ities cited, we respectfully submit that the rulings and the

judgment of the trial court be reversed, or in the alterna

tive, that the same be reversed with directions from this

Honorable Court, or in the further alternative, that this

Honorable Court enter such order or orders as in its judg

ment is meet and proper to grant Appellant relief in the

premises.

Respectfully submitted,

M oore, M in g & L e ig h t o n ,

Attorneys for Appellant.

C h r is t o p h e r C . W im b is h

G eorge N . L e ig h t o n

Of Counsel