English v. Town of Huntington Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. English v. Town of Huntington Brief for Appellants, 1971. c47760d5-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/080084e6-3239-4c87-9b27-028c78c82867/english-v-town-of-huntington-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

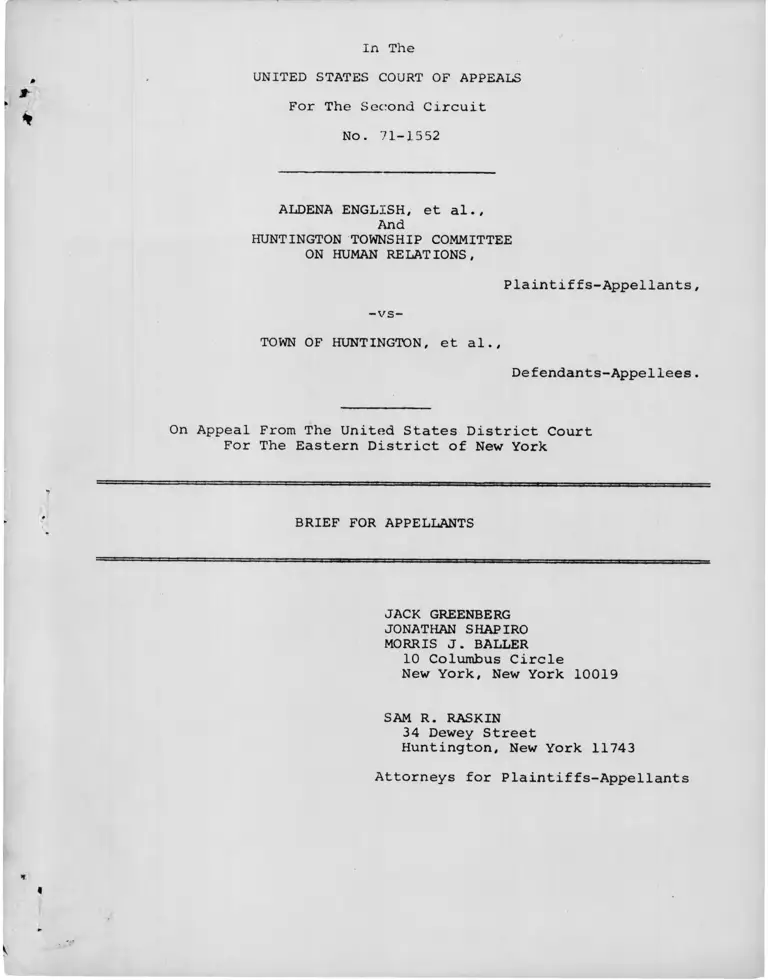

In The

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For The Second Circuit

No. 71-1552

ALDENA ENGLISH, et al.,

And

HUNTINGTON TOWNSHIP COMMITTEE

ON HUMAN RELATIONS,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

-vs-

TOWN OF HUNTINGTON, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District of New York

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

MORRIS J. BALLER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

SAM R. RASKIN

34 Dewey Street

Huntington, New York 11743

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

* «

j,

I N D E X

Preliminary Statement ................................ i

Issues Presented for Review .......................... 1

Page

Statement of the Case ................................ 3

Statement of Facts ................................... 6

Argument ..................................... 13

I . The Displacement From Their Homes of

Black and Puerto Rican Residents

of Huntington As A Result of Code

Enforcement Violates The Equal

Protection Clause of The Fourteenth

Amendment When The Displacees Are

Unable To Relocate Within The Com

munity Largely Because of Their Race ...... 13

II.

s

The Displacement of Persons From Their

Homes By Code Enforcement In The Absence

of Any Relocation Housing Constitutes

An Arbitrary Exercise of The Police Power

Which Violates The Rights of The Dis

placees, Protected By The Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Not To Be Deprived of the Only Housing That

is Available To Them In The Community

in Which They Live ........................ 26

III. The Code Enforcement Proceedings Should

Be Enjoined Because The Displacement of

The Tenants From Huntington Is a Direct

Consequence of the Town's Failure to

Adequately Relocate the Displacees From

the Urban Renewal Area in Violation of

42 U.S .C. § 1455 (c)........................ 32

IV. The District Court Erred In Denying Injunctive

Relief On The Ground That The Prospective

Displacees Are Not Members Of The Class

Which Plaintiffs Represent ................ 39

Conclusion

Table of Cases

Adkins v. Children's Hospital, 261 U.S. 525

(1923) .................................. • 31

1 1

Page

Arrington v. City of Fairfield, 414 F.2d 687(5th Cir. 1969) .......................... 17, 24

Buchanai v. Warley, 345 U.S. 60 (1917) ........ 28

Build of Buffalo, Inc. v. Sedita, F.2d

(2d Cir. No. 34886, April 13, 1971) ...... 41

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365

U.S. 715 (1961) .......................... 15

Carr v. Conoco Plastics, Inc., 423 F.2d 57

(5th Cir. 1970) .......................... 41

Clark v. Romney, 321 F. Supp. 458 (S.D. N.Y.(1970) ................................... 38

Clearfield Trust Co. v. United States, 318 U.S. 363 (1943) .................... ....... 36

Edwards v. California, 314 U.S. 160 (1941) .... 29

Fitzgerald v. Pan American World Airways, 229

F. 2d 499 (2d Cir. 1956) .................. 36

Garrett v. City of Hamtramck, F. Supp. ,

(CCH Pov. L. Rep. f 9994 (E.D. Mich No.

32004, March 7, 1969) .................... 19, 35

Goldblatt v. Town of Hempstead, 369 U.S. 590(1962) ................................26, 27, 28, 29

Gomex v. Florida State Employment Service, 417

F.2d 569 (5th Cir. 1969) .................. 37

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960)....14, 24, 29

Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, 437 F.2d 1286 (5th Cir.

1971) ..................................... 15, 14

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 389 (1969) ....... 16

J. I. Case Co. v. Borak, 377 U.S. 426 (1964) ... 36

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 F.2d

1122 (5th Cir. 1969) ...................... 41

*

ill

Kennedy Parks Homes Ass'n v. City of

Lackawanna, 436 F.2d 108 (2d Cir, 1970), cert, denied, 28 L.Ed.2d 546 (April 6,1971) ........................14,15,17,19,20,22,24,28

Lockner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905) .......... 31

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) .............. 14

Norwalk CORE v. David Katz & Sons, Inc., 410

F. 2d 532 (2d Cir. 1969) ....................... 38

Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency,

395 F . 2 d 920 (2d Cir. 1968)......... 15,17,23,29,35,40

Palmer v. Thompson, ___ U.S. ___, 39 L.W. 4759(June 14, 1971) ............................... 14, 20

Powelton Civic Home Owners Ass'n v. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 284 F. Supp.

809 (E.D. Pa. 1968) ........................... 35

Reitmeister v. Reitmeister, 162 F.2d 791 (2d Cir.

1947) 36

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) ........... 16, 28

Shannon v. Department of Housing and Urban

Development, 436 F.2d 809 (3rd Cir. 1970) .....35, 36

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969)...... 22,24,29,31

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ............ 28

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) .............. 14

Southern Alameda Spanish Speaking Organization v.

City of Union City, 424 F.2d 291 (9th Cir. 1970) ...15, 40

Taussig v. Wellington, Inc., 313 F.2d 472 (3rdCir. 1963) 36

T. B. Harms Company v. Eliscu, 399 F.2d 823 (2d

Cir. 1964) 36

Tunstall v . Brotherhood of Locomotive F. & E.,

323 U.S. 210 (1944) 36

Western Addition Community Organization v. Weaver,

294 F.Supp. 433 (N.D. Cal. 1968) 35

Page

XV

Page

Whirl v. Kern, 407 F.2d 787 (5th Cir. 1969)..... 14

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 3 56 (1886) ........ 14

Statutes

Uniform Relocation Assistance and Land Acquisition Policies Act of 1970, Public Law 91-646, 91st Cong.S. 1, 84 Stat. 1894 ............................. 29

Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure Rule 8 (a).... 6

United States Census of Housing and Population,1970 ............................................ 7

United States Code Congr. Service, 81st Cong.,1st Sess., pp. 1555-1561 (1949) .................. 35

United States Code:

12 U.S.C. § 1701(h)(i)(d) (Cum. Supp. 1971)___ 2242 U.S.C. § 1423 .............................. 21

42 U.S.C. § 1451(c) 29

42 U.S.C. § 1455 (Cum. Supp. 1971)___2,29,34,35,37

Urban Renewal Handbook,RHA 7100.1 ............... 29

In The

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For The Second Circuit

No. 71-1552

ALDENA ENGLISH, et al.,And

HUNTINGTON TOWNSHIP COMMITTEE

ON HUMAN RELATIONS,

Plaintiff s-Appe Hants

-vs-

TOWN OF HUNTINGTON, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District of New York

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Preliminary Statement

This is an appeal from an order denying a motion for a pre

liminary injunction entered on May 13, 1971 by the Honorable

Anthony J. Travia, United States District Judge for the Eastern

District of New York. The order is unreported and is reproduced

at page 245a of the Appendix.

Issues Presented For Review

1. Whether the displacement from their homes of low income

black and Puerto Rican residents by a municipality as a result

of the enforcement of a municipal zoning ordinance should be

enjoined as a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amemdment when the displacees will be forced to

leave the community largely because of racial discrimination

in the private housing market?

2. Whether code enforcement proceedings which displace

persons from their homes when no relocation housing is available

violate the rights of displacees, protected by the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, not to be deprived of the

only housing available to them in the community in which they

live?

3. Whether the code enforcement proceedings should also be

enjoined because the displacement is a direct consequence of

Town's failure to adequately relocate the displacees from the

urban renewal area in violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1455(c)?

4. Whether the district court erred in holding that the low

income black and Puerto Rican tenants of the houses against which

the Town of Huntington is proceeding with code enforcement actions

are not members of the class which plaintiffs represent?

-2-

Statement of the Case

On February 7, 1969, plaintiffs-appellants (the

"plaintiffs") filed this action in the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of New York

seeking injunctive and declaratory relief against var

ious officials of the Town of Huntington, New York

(the "local defendants") and against the Secretary and

Regional Administrator of the United States Department

of Housing and Urban Development (the "federal defendants").

It was brought as a class action on behalf of all of the

"black and Puerto Rican residents of the Town who are being

and have been deprived of their rights to equal housing op

portunities" (A. 3a). Plaintiffs seek generally to require

the local defendants to take affirmative steps to remedy

the discriminatory effects upon the low-income minority

group residents of Huntington of the housing policies of

1/the Town, and to enjoin both the local and federal defendants

from continuing to take action which had created and was

1/ The prayer for relief includes a request that the local

defendants be directed to construct additional units of

low-rent housing in Huntington and that the Town's zon

ing ordinance be declared unconstitutional to the extent

that it bars the construction of multiple dwelling houses

or inexpensive single family houses (A. 16a).

-3-

exacerbating the hardships imposed upon nonwhites.

Specifically, plaintiffs sought to enjoin the dis

placement without adequate relocation of members of their

class from the site of an urban renewal project financed

by the federal defendants and to require the construction

in the urban renewal area of a number of dwelling units

available to low-income minority groups that was at least

equal to the number of units destroyed by the project

(A. 10a, 16a). They also sought to enjoin any code en

forcement actions by the Town which would result in the dis

placement of members of plaintiffs' class from their homes

unless adequate relocation housing was provided in Huntington

(A. 12a-13a) .

On July 2, 1970, the district court denied motions to

dismiss filed by both the local and the federal defendants.

The court held that it had subject matter and personal jur

isdiction with respect to all defendants, that the complaint

sufficiently stated claims for relief, and that the suit was

properly maintainable as a class action (A. 45a-63a)

On November 20, 1970, plaintiffs moved for a preliminary

2/ See 42 U.S.C. § 1455 (Cum. Supp. 1971). Subsequent to

the filing of this action, the local defendants amended

the urban renewal plan in such a way as to double the

number of apartments that would be available to low-

income tenants in the urban renewal project area. Al

though construction of these apartments was scheduled to begin in the Spring of 1970, no work has yet begun

(Local Defendants' Answer to Interrogatory No. 15, p.10, dated October 6, 1969).

-4-

injunction to enjoin local defendants from commencing code

enforcement proceedings in state court against a number of

homes in a ghetto area of the town (A. 63a). Plaintiffs

contended that these proceedings would result in the dis

placement from their homes of many low-income black and

Puerto Rican residents who, because of the unavailability

of any relocation housing in Huntington, would be forced out

of the community (A. 67a). At a hearing held on November

24th, the local defendants acknowledged that they intended to

commence suits to enjoin violations of the Town's zoning or

dinance caused by overcrowding in four single-family houses

in a section of Huntington known as Greenlawn (A. 120a, 124a,

182a). They admitted that their action would result in the

eviction from their homes of seventeen families; they did not

dispute plaintiffs' showing that all of these persons were

low-income black or Puerto Rican residents who would be com

pletely unable to relocate in Huntington (A. 119a-126a); and

they disclaimed any responsibility for assisting these fami

lies to relocate within the town (A. 86a).

The district court denied plaintiffs' motion from the

1/

bench on April 23, 1971. The court did not make any findings

3/ it apparently concluded that only displacees from the urban

renewal area could properly be considered members of plain

tiffs ' class on whose behalf plaintiffs were entitled to

challenge the Town's action (A. 216a-217a, 232a). Conse

quently, solely upon the basis of the Town's representation that none of the tenants of the four houses had previously

resided in the urban renewal areas, it summarily denied

plaintiffs motion (A. 236a). The local defendants had agreed

not to commence the code enforcement actions during the period from November 24, 1970 to April 23, 1971. At the November

-5-

of fact nor did it issue any opinion explaining its ruling.

In the colloquy with counsel during the hearing, however,

the court indicated that it believed that only persons who

had been displaced from the urban renewal area and relocated

in the first instance by the Town in one of the overcrowded

houses against which the Town was proceeding would be en

titled to relief (A. 2l5a-218a).

An order denying the motion was entered on May 13, 1971

(A. 245a) and plaintiffs filed their notice of appeal on May

18th (A. 246a) . On May 21st, the district court denied a

motion, pursuant to Rule 8 (a) of the Federal Rules of Appellate

Procedure,for an injunction pending appeal (A. 247a). By no

tice of motion dated June 4, 1971, plaintiffs sought an in

junction pending appeal and an expedited appeal in this Court.

This Court issued an injunction pending appeal on June 16th

and scheduled argument on the merits for the week of July

12th (A. 266a) .

Statement of Facts

The Town of Huntington is located in Suffolk County,

New York, and comprises roughly the northwest quarter of

that county in area. According to the 1970 census, its

present population is 200,588, of which 194,540, or 97%, is

3/ (Cont'd)

24th hearing, the court had requested that the defendants

provide certain information and suggested that they delay their action until he had ruled (A. 192a-196a). Although

this information was to be provided within several days,

the defendants did not file their affidavit containing it until April 13, 1971 (A. 199a).

-6-

white and 6,048, or 3%, is nonwhite. During the last

decade, Huntington has undergone a rapid, if not phenon-

menal, population explosion. The growth of the metropol

itan area suburbs, improved transportation and the location

of industry and jobs all have contributed to ar. almost 60%

increase over the 1960 population of 126,221. At the same

time the nonwhite population increased at even a greater

rate so that at present it represents a 110% increase over

the 1960 population of 2875.

Against the background of this dramatic population

growth and widespread racial discrimination in the private

housing markets, the policies of the local defendants have

resulted in the development of racial ghettos in the town

where much of Huntington's nonwhite population is forced

to live in overcrowded, detriorating housing units. Siice

this is the only housing readily available to nonwhites,

their displacement from their homes is tantamount to dis

placement from Huntington altogether.

There can be no question that racial discrimination in

Huntington has severely limited the housing that is open to

blacks and Puerto Ricans. The district court noted the

existence of such widespread discrimination (A. 50a) and

the Town Housing Authority, one of the local defendants, has

4/ These figures are based on the first count of the 1970

United States Census of Housing and Population.

-7-

recognized that racial discrimination is in large part

responsible for the creation of ghettos in Huntington

(A. 77a). The full effect of this discrimination on the

housing opportunities of minority group residents is shown

by the census figures. According to the special 1967 cen

sus, 81.1% of all nonwhites in Huntington lived in six out

of the total of twenty-seven census tracts. And between

1960 and 1967, the nonwhite population outside of these

six tracts increased by only seven persons (A. 251a).

In light of the special difficulties which nonwhites

face in obtaining housing, it is evident that any govern

mental action which limits or reduces the total housing

supply will bear most harshly upon them. Yet, since 1960

the Town has demolished through code enforcement and urban

renewal approximately 700 dwelling units that were among

the most accessible to nonwhites (A. 103a). The largest

single factor in these demolitions was the Huntington

Station Urban Renewal Project which displaced over 240

households, approximately 75% of which were black and Puerto

Rican (A. 103a).

The Town has done almost nothing, furthermore, to re

place the housing that it has destroyed. In 1967 it con

structed a total of only forty units of public housing, a

number that was even insufficient to accommodate the eighty-

seven households displaced by urban renewal who were eligible

for public housing (A. 102a,103a). On the contrary, the

Town's policies have provided a substantial obstacle to the

-8-

provision, by the public or private sector, of new housing

that would benefit low—income minority group residents. It

has refused to approve a proposal by the Housing Authority

for the immediate construction of at least one hundred fed-

erally-financed public housing units (A. 67a-68a). It has

also continued since 1960 a moratorium on the construction

of multiple dwelling homes, despite the recommendation in

1964 by its own planning consultants that it amend its zon

ing laws so as to permit the construction of at least 3000

additional apartments by 1980. As a result, 16,424 of the

privately built housing units since 1960 have been single

6/family homes and 189 have been two family homes. The rapid

use of vacant land in this way will soon make it impossible,

under present zoning restrictions, to construct enough housing

to eliminate the shortage (A. 74a).

The actions of the Town in reducing the housing supply

available to the rapidly expanding black and Puerto Rican

population in a housing market pervaded by racial discrimina

tion and in preventing its replacement has had the inevitable

effect of creating racial ghettos of overcrowded, substandard

housing (A. 68a-69a, 98a, 102a, 251a). As early as 1960,

in the three census tracts containing the largest nonwhite

5/ The Housing Authority requested approval for the construct

ion of sixty units of public housing as early as 1967 (A.

105a). A program reservation of funds of these units made

by HUD was cancelled in 1969 because of the unwillingness

of the Town to enter into the necessary cooperation agreement (A. 74a).

6/ The average price of a single family home is over $30,000. (A. 73a).

-9-

population, there were almost four times as many dilapi

dated and deteriorating housing units as in the town as

a whole (A. 251a-252a). The staff of the Nassau-Suffolk

Regional Planning Commission recently estimated that one

thousand publicly-assisted housing units would be nec

essary just to relocate households living in overcrowded

homes in Huntington (A. 85a). The Housing Authority has

itself recognized the need for the construction of 1400

low-income housing units (A. 67a, 85a). And a subcommittee

of the Citizens Advisory Committee to the urban renewal

project has called for the construction of low-income

housing for people who must be displaced in order to elim

inate illegal apartments (A. 92a). The results of these

conditions were documented by plaintiffs who found that at

least forty of the black and Puerto Rican households dis

placed by the urban renewal project were relocated into

1/illegal, overcrowded apartments (A. 104a).

The Town has done almost nothing to alleviate the

overcrowded conditions and to arrest the deterioration of

the housing supply in these neighborhoods. As conditions

have grown steadily worse over the past several years, the

Town has explicitly refrained from any systematic code en

forcement on the ground that relocation housing would only

be available after the apartments in urban renewal projects

7/ See Exhibit A to Plaintiffs1 Answers to Interrogatories, dated October 2, 1969. At least six of these households

were relocated into overcrowded dwellings in the Greenlawn

section at Huntington (A. 98a).

-10-

(construction of which has not yet begun) had been com-

8/pleted. Otherwise, the local defendants have completely

ignored or rejected the proposals that might begin to provide

a solution. They are opposed to the construction of any more

low-rent housing and have even ruled out a code enforcement

program with federal financial assistance on the ground that

federal requirements for the provision of relocation housing

would force the Town "to go into public housing beyond [its]

power to pay" (A. 95a).

Whether the code enforcement proceedings which the local

defendants now plan to commence is part of a purposeful scheme

i/to reduce Huntington's nonwhite population is not clear.

8/ The Housing Authority has pointed out that even if all of the 250 cooperative apartments planned in the urban renewal

area were made available for low-income tenants it would

not come close to solving the problem of overcrowded, sub

standard housing. In fact, only 50 apartments will be

available to low-income families (A. 73a). In light of

the number of households that were displaced from the urban

renewal area and forced to move into illegal, overcrowded

apartments, however, it is clear that systematic code enforce

ment at that time would have held up the urban renewal

project. In addition, if the Town had displaced households

through code enforcement without providing relocation housing, it would have been ineligible for recertification

of its Workable Program for Community Improvement, a con

dition for the receipt of most HUD assistance (See RHA

§ 7100.1). Indeed, on April 22, 1970 HUD refused to recertify

the Town's Workable Program on the ground, inter alia, that

the "application failed to show what is being done or what

is proposed to augment the housing supply to provide new

units for displacees, especially those of low or moderate

income." (Federal Defendants' Answer to Interrogatories

Nos. 18 and 21, dated September 30, 1970).

9/ Although the local defendants have admitted only to plans to

commence actions against four houses, they appear to con

template systematic enforcement in the future (A. 86a).

-11-

What is clear, however, is that the impending proceedings will

result in displacing at least seventeen black and Puerto

Rican families from their homes and forcing them to leave

Huntington. These families will be separated from their jobs,

their children's education will be interrupted and they will

be forced to seek a new home in a different community at a

time when housing everywhere for low-income nonwhites faces

its most critical shortage.

-12-

ARGUMENT

I

The Displacement From Their Homes

of Black and Puerto Rican Residents

of Huntington As A Result of Code

Enforcement Violates the Equal Pro

tection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment When The Displacees Are

Unable To Relocate Within The Com

munity Largely Because of Their Race.

The facts in the present record are largely undisputed.

Defendants have not denied that their policies have had

the effect of reducing the supply of housing available

to minority group residents nor have they denied that

the impact of their actions has especially disadvantaged

the black and Puerto Rican residents of Huntington whose

housing market is greatly limited by racial discrimination.

Indeed, defendants do not deny the existence of overcrowded

and deteriorating housing conditions in nonwhite neighbor

hoods or the inability of a nonwhite displacee to relocate

within Huntington. Instead, the local defendants baldly

assert that the Town's interest in eliminating illegal apart-

justifies actions which have the effect of driving its

nonwhite residents out of Huntington. We submit that this

action violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment because the Town's interest is not sufficiently

compelling to justify the discriminatory impact of the code

enforcement proceedings.

It is well established when governmental action is chal

lenged as being violative of equal protection that the focus

-13-

of judicial inquiry is the actual effect, rather than the

purpose or motivation, of the action. Palmer v. Thompson,

___U.S. ____, 39 L. W. 4759, 4761 (June 14, 1971);

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339, 341 (1960) ; Smith

v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128, 132 (1940) ; Yick Wo v. Hopkins.

118 U.S. 356 (1886). "[I]n a civil rights suit alleging

racial discrimination in contravention of the Fourteenth

Amendment, actual intent or motive need not be directly

proved." Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, 437 F.2d 1286, 1291 (5th

Cir. 1971) (petition for rehearing en banc granted). The

absence of an invidious discriminatory design is essentially

irrelevant, for the unjustified, unequal treatment of non

whites is clearly within the prohibition of the civil rights

act which "makes a man responsible for the natural conse

quences of his actions." Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961)

see Kennedy Park Homes Ass'n v. City of Lackawanna, 436 F.2d

108, 114 (2d Cir. 1970) cert. denied, 28 L.ed.2d 546 (April

6, 1971) ; Whirl v. Kern, 407 F.2d 787 (5th Cir. 1969) . As

the Supreme Court said in Monore v. Pape, supra:

"It is abundantly clear that one reason

the legislation was passed was to afford

a federal right in federal courts because,

by reason of prejudice, passion, neglect,

intolerance, or otherwise, state laws

might not be enforced and the claims of

citizens to the enjoyment of rights, priv

ileges and immunities guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment might be denied by

the state agencies" (emphasis added) (365

U.S . at 180) .

Racial discrimination is constitutionally prohibited regard

less of whether it results from

-14-

deliberate hostility or from mere indifference, since

"it is of no consolation to an individual denied the

equal protection of the laws that it was done in good

faith." Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority. 365 U.S.

715, 725 (1961).

Thus, as this Court has stated:

'"Equal protection of the laws' means

more than merely the absence of governmental action designed to discriminate;

• . .'we now firmly recognize that the

arbitrary quality of thoughtlessness can be as disastrous and unfair to pri

vate rights and the public interest as the perversity of a wilful scheme'."

(Norwalk CORE v . Norwalk Redevelopment

Agency, 395 F.2d 920, 931 (2d Cir. 1968)).

Accord, Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, supra; Southern Alameda

Spanish Speaking Organization (SASSO) v. City of Union

City, 424 F.2d 291 (9th Cir. 1970). Only recently, more

over, this Court has reaffirmed its view that a specific

purpose to discriminate on the basis of race need not be

proved in order to establish a violation of equal pro

tection. in Kennedy Park Homes Ass'n v. City of Lackawanna.

436 F.2d 108 (2d Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 28 L.Ed.2d 546

(April 6, 1971), retired Justice Clark, sitting by designa

tion, spoke for the Court in condemning a municipality's

refusal to allow the construction of a black housing project

in an all-white neighborhood based on its contention that

the sanitary sewers were inadequate to handle the increased

burden. He said:

-15-

"Even were we to accept City's allegation that any discrimination here resulted

from thoughtlessness rather than a purposeful scheme, the City may not escape

responsibility for placing its black

citizens under a severe disadvantage which it cannot justify" (436 F.2d at 114).

The threshold question in the present case then is

whether the action of the Town of Huntington sought to be

enjoined will cause special hardships for its black and

Puerto Rican residents with which they would not be faced

if not for their race. In making such a determination,

the factual inquiry is necessarily broad. Not only is the

immediate objective of the government relevant, but the

"historical context" and the "ultimate effect" of the

action must be considered as well. Reitman v. Mu1key, 387

U.S. 369, 373 (1967), and the reality of the impact of

state action can only be assessed in the factual context

in which it takes place. Hunter v. Erickson. 393 U.S. 389,

391 (1969) .

The record in this case establishes that the immediate

effect of the code enforcement proceedings brought by the

local defendants will be to drive seventeen black and Puerto

Rican families out of Huntington. It also establishes that

such displacement is directly related to the existence of

racial discrimination in the private housing market which

severely limits the availability of relocation housing

in the town. In this way, the local defendants are acting

"so as to compound the problem of racial discrimination in

the [Huntington] housing market, with the inevitable and

-16-

intended result that some Negroes and Puerto Ricans would

be forced to leave the city altogether." Norwalk CORE v.

Norwalk Redevelopment Agency, supra, 395 F.2d at 926.

When confronted with a closely similar situation in

Norwalk CORE, this Court said:

"It is no secret that in the present state

of our society discrimination in the housing market means that a change for the

worse is generally more likely for members

of minority races than for other displacees.

This means that in many cases the relocation standard will be easier to meet for

white than for non-white displacees. But

the fact that the discrimination is not in

herent in the administration of the program, but is, in the words of the District Court,

'accidental to the plan,1 surely does not

excuse the planners from making sure that

there is available relocation housing for all displacees" (395 F.2d at 931).

Similarly, in Kennedy Park Homes Ass'n. supra, the

Court held that the deprivation of the ability of black

residents of a city to live in the same areas as whites

which may have unintentionally resulted from the combina

tion of private racial discrimination in housing and the

City's attenpt to deal with a sewer problem constituted a

violation of equal protection. And in Arrington v. City

of Fairfield, 414 F.2d 687 (5th Cir. 1969), the Fifth

Circuit reversed the dismissal of a complaint alleging

that the commercial redevelopment of a blighted residential

area in which the municipality was participating would re

sult in forcing a large number of poor black residents of

the area to leave the city because of the unavailability

-17-

The Court con-of any other place for them to relocate,

eluded:

" [P]laintiffs may be able to show that

the City will knowingly actively precipitate

the dislocation of persons who, because of a

city-wide practice of residential discrimination will have no place to go. Exclusion

by physical displacement is no less object

ionable than such exclusion by rezoning.

Where there is state involvement, the fact that the decision to discriminate may be

made by private individuals rather than a

public official is not decisive" (414 F.2d at

Thus, a municipality is accountable under the Fourteenth

Amendment and § 1983 when its otherwise neutral action has

a racially discriminatory impact because of its failure to

consider the discriminatory context m which it was operat

ing.

The responsibility of the local defendants for the dis

criminatory displacement of members of plaintiffs1 class is

based upon far more than their failure to compensate for

racial discrimination in the private housing market in con

nection with the code enforcement proceedings at issue here.

1 0/

For, as documented above, the defendants have consistently

acted in the past in such a way as to create the conditions

which have deprived the nonwhite residents of Huntington of

adequate housing. Indeed, the overcrowded illegal apartments,

.10/ See pp. 7-11, supra.

-18-

occupied by low-income blacks and Puerto Ricans which

the Town now seeks to eliminate are directly attributable

to the Town's flagrant disregard of the interests of these

minority group residents in its housing policies. In its

"historical context"/ the Town which has forced much of

its nonwhite population into several ghetto areas where

overcrowding had increased and housing conditions have

deteriorated, now seeks to eliminate the overcrowding at

the expense of the already disadvantaged blacks and Puerto

Ricans. The actions of the Town of Huntington, therefore,

have paralleled those of the City of Lackawanna which this

Court concluded represent "state action amounting to spe

cific authorization and continous encouragement of racial

discrimination, if not almost complete racial segregation."

Kennedy Park Homes Ass'n v. City of Lackawanna, supra, 436

F.2d at 114.

The ultimate impact of the Town's action will be devasta

ting. While it apparently plans to systematically eliminate

illegal apartments through code enforcement, it has no plans

to provide any housing in the town for the families who will

be displaced. In light of the extent of overcrowding in

areas of high minority group concentration, it is evident

that the large numbers of blacks and Puerto Ricans will

inevitably be forced out of Huntington. The code enforce

ment actions in the present case, like the urban renewal

program in Garrett v. City of Ilamtramck, ___ F.Supp. ___,

(CCH Pov.L.Rep. 5 9994 (E.D. Mich. No. 32004, March 7, 1969)),

-19-

"if allowed to continue without some guarantee that low-

cost housing will be made available, will result in the

very 'Negro removal' of which plaintiffs complain" (Slip.

11/

op. p • 7) .

Once having established that the Town’s action sub

jects black and Puerto Rican residents to a disproportion

ate burden because of their race, there remains only to

consider whether that action can be justified by a showing

that it serves a compelling state interest. In light of

the fact that the central purpose of the Fourteenth Amend

ment was to being about racial equality under the law,

Palmer v. Thompson, supra, 39 L.W. at 4759, any govern

mental action which subjects a racial minority to special

hardships "bears a heavy burden of justification. . .and will

be upheld only if it is necessary and not merely rationally

related to the accomplishment of a permissible state policy."

Where such racial discrimination is shown, moreover, the

officials "must show a compelling governmental interest in

order to overcome a finding of unconstitutionality„"

Kennedy Park Homes Ass'n v. City of Lackawanna, supra, 436

F.2d at 114.

The Town seeks to justify its actions solely on the

basis of its interest in eliminating the spread of blight

in housing. While this is unquestionably a legitimate

governmental objective, it need not be accomplished at the

11/ in this case, the district court enjoined an urban renewal

project on the ground that it failed to provide a suffi

cient number of low-cost dwelling units to provide for the

-20-

cost of driving nonwhite residents out of Huntington.

Alternative means are readily available to the local de

fendants whereby they can eliminate illegal apartments

and at the same time provide decent housing in the own

for families that are displaced. At a minimum, they can

make efforts to relocate the families by assisting them

to find and rent housing that is available on the private

market. Where apartments are refused because of racial

discrimination, the Town Attorney is authorized to initiate

12/proceedings before the State Division of Human Rights. The

Town can also provide housing for low-income residents

relatively quickly through the federally financed leased

13/housing program. The Housing Authority would be authorxzed

to lease existing vacant dwellings on the private market and

rent them to low-income families at approximately 20% of

their income. Of course, the ultimate solution lies only

in the expansion of the existing housing supply available to

11/ (Cont'd)

relocation of households who would be displaced in the

future as a result of the city's plans to demolish sev

eral black neighborhoods. The land in the urban re

newal area was realistically the only place in the city

where relocation housing for future displacement could be constructed.

12/ See Local Defendants' Answers to Interrogatories Nos. 52, 53, 54, dated October 6, 1969.

13/ See 42 U.S.C. § 1423.

-21-

low and middle income blacks and Puerto Ricans. The con

struction of additional units of public housing, increasing

the numbers of apartments in the urban renewal project with

14/respect to which rent supplement payment can be made, and

the encouragement of private building of low and middle-

income multiple dwellings is a necessary beginning to a hous

ing program which will make decent housing available to

Huntington's racial minorities.

Thus, there clearly exist means by which the Town can

prevent the enforcement of its zoning code from disadvan

taging its nonwhite residents. And the Supreme Court has

held that where "less drastic means are available" to fur-

there a legitimate governmental policy, it is unreasonable

to accomplish the objective at the expense of fundamental

interests. Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618, 637 (1969).

So long as it makes a concurrent effort to rehouse the fam

ilies who are displaced as a result of code enforcement the

interests of both the Town and the displacees can be ade

quately served.

In Kennedy Park Homes Ass'n. supra, this Court held

that the city could not justify its refusal to permit the

construction of a housing project sponsored by its black resi

dents in an all-white neighborhood on the ground that the

14/ See U.S.C. § 1701 (h) (i) (d) (Cum. Supp. 1971). Tie Town

could provide rent supplements with respect to 40%, or

104, of the 260 cooperatives which are planned in the

urban renewal area. Present plans call for rent supplements for only 20%, or 52, of the apartments (A. 73a).

-22-

sewer system was xnadequate. Instead, the city was ordered

to permit the construction of the project and to take all

necessary steps to improve the sewers. 436 F.2d at 114.

In Norwalk CORE, supra, this Court held that the city's

interest in the execution of an urban renewal project could

not justify the special difficulties faced by blacks and

Puerto Rican displacees in finding relocation housing within

the city. in such a situation, the plaintiffs would be en

titled to enjoin further displacement. 395 F.2d at 925-26.

By the same token, the Town of Huntington's interest in

eliminating illegal apartments cannot justify forcing non

white residents to leave the town. Accordingly, the local

defendants should be enjoined from such displacement until

adequate relocation housing is made available.

The Town s adamant refusal to make any effort to provide

housing, even with substantial federal assistance, for its

residents who will be displaced by code enforcement indicates

that the only real interest at stake here is the Town's abil

ity to continue to ignore the welfare of its low-income non

white citizens. It is immaterial whether the Town is pursuing

15/ The local defendants have refused to enter into a coop

eration agreement which would have enabled the Housing

Authority to construct at least 60 units of public hous- lng (A. 105a), and they have rejected the possibility

of utilizing a federally-assisted code enforcement pro- gram which would provide funds for relocation assistance (A. 86a). See 42 U.S.C. § 1468 (Cum. Supp. 1971).

-23-

such a course because it intends to eliminate its low-

income black and Puerto Rican population, see e.g.

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, supra; Arrington v. City of

Fairfield, supra, or because it is simply unwilling to

spend the money to provide additional housing (A. 95a).

In either case it is clear that the policy is not so com

pelling as to justify the drastic consequences of dis

placement from the town of many black and Puerto Rican

families. See Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618, 633

(1969); Kennedy Park Homes Ass'n, supra, 436 F.2d at 114.

Finally, the claimed urgency of the impending code en

forcement proceedings is belied by the Town's neglect in

seeking to eliminate illegal apartments in the past. Indeed,

by refraining in the past from systematic code enforcement

because of the unavailability of any relocation housing the

local defendants have at least tacitly recognized that

their obligation to provide relocation for persons who will

be displaced is more important than the need to correct

16/

the violations. The lack of urgency in the enforcement of

the zoning ordinance is exemplified by the four threatened

16/ See the Town’s applications for recertification of its

Workable Program for Community Improvement, dated May 14, 1968, p. 22 and dated December 31, 1969, p. 3. They

are part of the record as plaintiffs' Exhibits C and D

to the hearing of April 23, 1971.

-24-

proceedings at issue here. Despite the discovery of

the allegedly illegal conditions in July, 1970, legal

proceedings did not become imminent until November,

1970 (A. 86a). And after the filing of plaintiffs'

motion to enjoin the displacement, the Town was respon

sible for a delay of over four months in the decision of

the motion during which time no action was taken (A. 252a).

It is plain, therefore, that no emergency exists which

requires immediate action.

Since no compelling governmental interest has been

shown, the commencement of code enforcement proceedings

by the local defendants would deny the equal protection

of the laws to low-income black and Puerto Rican residents

who, largely because of their race, would be forced to

leave Huntington as a result. Consequently, the Town

should be enjoined from the enforcement of the zoning

ordinance, the impact of which falls so unevenly upon

racial minorities, until it accompanies its action with

efforts which ameliorate and compensate for its discrimin-

tory effects.

-25-

II

The Displacement of Persons From Their Homes

By Code Enforcement In The Absence of Any Re

location Housing Constitutes An Arbitrary Exercise of The Police Power Which Violates The

Rights of the Displacees, Protected By The Due

Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.Not To Be Deprived of the Only Housing That Is

Available to Them In The Community In Which They Live.

Plaintiffs have shown above that the displacements caused

by the threatened code enforcement proceedings will have a

racially discriminatory impact upon low-income black and

Puerto Rican residents of Huntington which violates their

right to the equal protection of the laws. Such displacements

would also arbitrarily deprive them of the only housing that is

available to them in the community in which they live in viola

tion of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Fourteenth Amendment's prohibition against the depri

vation of life, liberty or property without due process of law

limits the extent to which a state can, in the exercise of its

police power, encroach upon individual interests. The standards

for determining when such constitutional limits have been ex

ceeded were stated by the Supreme Court in Goldblatt v. Town of

Hempstead. 369 U.S. 590, 594-95 (1962):

To justify the State in. . .interposing its

authority in behalf of the public, it must

appear first that the interests of the public

require such interference ; and second, that

the means are reasonably necessary for accom

plishment of the purpose, and not unduly oppressive upon individuals."

Thus, in judging the validity of the Town's action in the present

-26-

case the issue is whether the enforcement of its zoning code

is reasonable in light of the nature of the individual in

terests affected. Id. 369 U.S. at 595.

The first condideration to which we turn is whether the

interest of the public requires the enforcement of the zoning

code in Huntington. We do not question the propriety, or in

deed the necessity, of the enforcement of an ordinance directed

at the elimination of overcrowded housing units. There can be

no question that overcrowding of the kind that exists in

Huntington j_s in large part responsible for the deterioration

of the housing supply and the spread of blight. Nor is there

any question that overcrowded housing creates health and safety

hazards for its occupants. But under the circumstances of this

case, we think its enforcement without providing assistance to

the persons who will be left homeless as a result is so arbitrary

12/as to violate the Fourteenth Amendment.

In determining whether the public interest served by the

exercise of this police power justifies the encroachment on in

dividual rights, a court must consider "the availability of other

less drastic protective steps, and the loss which [plaintiffs]

will suffer from the imposition of the ordinance." Goldblatt v.

Town of Hempstead, supra, 369 U.S. at 595. We have already pointed

17/ The Town's intermittent and haphazard enforcement of its zon

ing ordinance in the past indicates that it did not consider

the public interest to require a systematic policy of code

enforcement (A. 250a-252a). We are not here faced with a

situation where the local defendants have consistently acted

to eliminate illegal apartments. Rather, the threatened proceedings represent an exception rather than the rule.

-2 7-

out that there are means readily available to the Town by

which it can eliminate overcrowded housing conditions and

minimize the hardships imposed on the families who are dis- 18/

placed. The expansion of the existing housing supply by

the construction of more public housing, an increase in the

number of apartments in the urban renewal project that will

receive rent supplements, and the elimination of multiple

dwelling zoning restrictions which make it impossible for

private enterprise to contribute to the solution of the prob

lem are all part of a less drastic and more lasting solution

to overcrowding. As a temporary solution, moreover, the Town

can provide relocation assistance to families who will be

displaced by code enforcement.

On the other hand, the enforcement of theordinance will,

m light of housing conditions in Huntington, be "unduly op

pressive upon individuals." Goldblatt v. Town of Hempstead,

supra, 369 U.S. at 595. The right not to be deprived by

public action of the only housing that is available in the com

munity in which one lives is indeed fundamental. See, e.g.,

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) ; Shelley v. Kraemer.

334 U.S. 1 (1948) ; Buchanan v. Warley, 345 U.S. 60 (1917) ;

Kennedy Park Homes v. City of Lackawanna, supra; SASSO v. City

18/ See pp. 21, 22, supra.

-2 8-

of Union City, supra; Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment

Agency, supra. It has been recognized by Congress in the

relocation requirements of the Housing Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1455,

and provides the basis for the recently enacted Uniform Re

location Assistance and Land Acquisition Policies Act of 1960.

Public Law 91-646, 91st Cong. S. 1, 84 Stat. 1894. And in its

workable program regulations the Department of Housing and

Urban Development has made the replacement of housing units

destroyed by any public action on a one-to-one basis and the

relocation of the occupants a requirement of most federal

assistance. See 42 U.S.C. § 1451(c) ; RHA 7100.01.

The ability to establish roots in a community, furthermore,

is the key to the enjoyment of other fundamental rights. Ac

cess to education for children, to employment opportunities,

to the electoral process, and to the benefits of other public

services all depend upon residence. See, e.g., Shapiro v.

Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969); Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S.

339 (1960) ; Edwards v. California, 314 U.S. 160 (1941) . The

disruption in the lives of low income blacks and Puerto Ricans

who are presently facing eviction will be especially great be

cause of the extreme difficulties they will face in relocating

anywhere.

Finally, to the factors set forth by the Supreme Court in

Goldblatt, supra, to be weighed in determining the reasonableness

of a particular exercise of a municipal police power, we add the

consideration of the municipality's responsibility for creating

-29-

the conditions which require the exercise of the power. For

where the municipality has brought about the violations of

its ordinance as a result of its own deliberate policies, it

is inequitable to permit it to eliminate the violation at the

expense of important private rights. In such a case the munic

ipality would only be penalizing individuals for its own fail

ure to act in the public interest.

But this would be precisely the effect of the Town's dis

placement of families from overcrowded houses without provid

ing relocation. In reducing the housing supply available to

low and middle income families and preventing its replenishment,

the Town has directly caused the overcrowding and is respon

sible for the unavailability of any relocation in Huntington

for the potential displacees. Indeed, the Town was only able

to carry out the demolition phase of the urban renewal project

by actually relocating many families into illegal apartments

, • • 12/of the kind it now seeks to eliminate. Thus, the Town shifted

the burden for the "progress" achieved by urban renewal

(which at present is measured only be vacant land and the net

reduction of over 200 critically needed housing units) onto the

displaced families who were inadequately located. It now plans

again to place the burden for eliminating the consequences of

its past policies upon those least able to bear it.

We submit, therefore, that the Town's interest in enforcing

its zoning ordinance cannot be justified in light of the extent

------------- -SO-

lO/ See pp. 32-33, infra.

of the individual injuries that will result and in light of

the far less drastic alternatives that are available to ac

complish the same goal. We do not by this argument seek to

revive long discredited notions of substantive due process.

See, e.g., Adkins v. Children's Hospital, 261 U.S. 525 (1923);

Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905). Rather, where the

right of a family not to be deprived of the only housing that

is available to it in the community in which it lives is at

stake, we think that the Town must make a more compelling show

ing to justify its action than it has in the present case. See

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969). The Town may not es

cape its own responsibility for its housing problem by sacri

ficing the fundamental interests of its residents but should in

stead, be required to utilize available alternatives to achieve

a more durable solution.

-31-

Ill

The Code Enforcement Proceedings Should

Be Enjoined Because The Displacement of The Tenants From Huntington Is a Direct

Consequence of the Town's Failure to

Adequately Relocate the Displacees From the Urban Renewal Area in Violation of

42 U.S.C. 5 1455(c).

The local defendants have not disputed plaintiffs'

showing that many black and Puerto Rican households that

were displaced as a result of the urban renewal project

were relocated into overcrowded, substandard dwellings in

ghetto areas of Huntington (A. 97a-98a). Plaintiffs have

shown that there were fifty-six families who were dis

placed from the urban renewal area that the Town did not

even carry on its relocation workload and, therefore, did

not assist (A. 167a, 191a, 207a-210a). At least sixty-six

of the displaced households, moreover, actually relocated

into dwellings which did not comply with federal standards

20/

(A. 68a, 104a). Of these, forty were illegal apartments

in overcrowded houses (A. 104a). The experience of the

five black and Puerto Rican plaintiffs is typical of the

21/inadequacy of the relocation housing provided by the Town.

Of the four families who moved into illegal apartments,

20/ See Exhibit A to Plaintiffs' Answers to Interrogatories, dated October 2, 1969.

2_1/ See Transcript of depositions of plaintiffs English,

Cofield, Whatley, Chambers and Elias, dated July 24,

1969 and filed May 10, 1971.

-32-

three were forced to separate because the space was in

sufficient (Tr. pp. 52-53, 100-101, 201-202). One family

returned to Puerto Rico because they could not find any

housing at all (Tr. p. 100).

The overall effect of the displacements from the

urban renewal area is clear. At a time when the local

defendants described the vacancy rate in Huntington as

22/

"nominal" and "miniscule," they were in the process of

displacing over 240 low and middle income households from

the urban renewal project area. Yet, despite such large

scale displacements into a housing market with essentially

no vacancies, the Town has provided only forty units of

new housing. And the construction of the proposed 260

middle income cooperative apartments (of which 50 will

receive rent supplements) in the project area has not

even begun.

There can be no doubt that the local defendants vio

lated their obligations under 42 U.S.C. § 1455(c)(1) to

insure that:

22/ Workable Program for Community Improvement, dated

December 31, 1967, pp. 10, 16 (Exhibit B to April 23, 1971 hearing).

-33-

"There shall be a feasible method for the

temporary relocation of individuals and

families displaced from the urban renewal

area, and there are or are being provided

in the urban renewal area or in other

areas not generally less desirable. . .decent, safe and sanitary dwellings equal

in number to the number of and available to such displaced individuals and fami

lies. . . "

The Town was required under § 1455(c)(2), moreover, to

provide assurance that decent, safe and sanitary dwellings

were available to every household that was displaced. But

not only did the defendants fail to provide adequate re

location by placing households in overcrowded substandard

dwellings, but to this date the urban renewal project has

resulted in a net reduction of over 200 units in the hous

ing supply available to low and middle income households.

The connection between these violations of § 1455(c)

and the fact that the families who will be displaced as a

result of the threatened code enforcement actions will be

forced to move out of Huntington is direct. For these fam

ilies will be displaced from the town because of the absence

of any relocation housing,and the absence of vacancies is

in large part attributable to the reduction in the housing

supply caused by urban renewal. Thus, if the local de

fendants are permitted to proceed with the planned code en

forcement, the displacees will suffer the consequences of

the Town's previous violation of § 1455(c), and the Town's

actions will result in precisely the injury that this section

-34-

was designed to prevent --a change for the worse for

households affected by urban renewal. See Norwalk CORE,

supraf 395 F.2d at 931; Western Addition Community

Organization v. Weaver, 294 F.Supp. 433 (N.D. Cal. 1968) ;

Garrett v. City of Hamtramck, supra.

The effect of this violation of federal law is in no

way diminished by the fact that no urban renewal displacee

is presently threatened with displacement. Since the ten

ants who stand to be displaced as a result of code enforce

ment will be injured as a consequence of the violation of

§ 1455(c), they clearly have standing to challenge the

Town's action. Shannon v. Department of Housing and Urban

Development, 436 F.2a 809 (3rd Cir. 1970) ; Powelton Civic

Home Owners Ass'n v . Department of Housing and Urban

Development, 284 F. Supp. 809 (E.D. Pa. 1968). The purpose

of § 1455(c) was not only to insure relocation for the actual

displacees of the urban renewal area, but to protect as well

the rest of the community from the blighting influences of

large reductions in the housing supply. See U.S. Code Congr.

Service, 81st Cong., 1st Sess.,pp. 1555-1561 (1949).

Nor should the fact that plaintiffs are seeking to enjoin

only the local defendants from inflicting the consequences

of the previous violation of their obligations under 1455(c)

upon the members of their class rather than to enjoin the

execution of the urban renewal project in the course of which

-3 5-

the violations took place make a difference. The Town's

obligation to provide adequate relocation is derived

from the capital grant contract which it entered into

with the federal defendants and its acceptance of funds

was conditioned upon its compliance with § 1455(c). Its

obligation is one which plaintiffs have standing to raise/

Shannon v. HUD, supra, and which must be determined as

a matter of federal law. Clearfield Trust Co. v. United

States, 318 U.S. 363 (1943).

We submit that the obligations imposed on the Town

by federal law and by the acceptance of federal funds must

be enforceable against the Town by persons directly affected

by their violation. This right of action on behalf of

members of plaintiffs' class, although nowhere specifically

authorized in the Housing Act, should be implied from its

language and purpose. Implied private remedies in the form

of civil actions based on federal regulatory statutes have

received recognition in a variety of statutory settings.

See, e.g., Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive F. & E.,

323 U.S. 210 (1944) (duty of fair representation under the

Railway Labor Act), and J. I. Case Co. v. Borak, 377 U.S.

426 (1964) (stockholder’s action under Securities Exchange

23/Act) ._____ In each case, the implied remedy has been considered

23/ See also, T. B. Harms Company v. Eliscu, 399 F.2d 823

(2d Cir. 1964) (action under copyright laws); Fitzgerald

v. Pan American World Airways, 229 F.2d 499 (2d Cir. 1956)

(action under Civil Aeronautics Act); Reitmeister v.

Reitmeister, 162 F.2d 691 (2d Cir. 1947) (action under

Federal Communications Act); Taussiq v. Wellington, Inc., 313 F.2d 472 (3rd Cir. 1963) .

-36-

necessary to effectuate the statutory purpose.

In Gomez v. Florida State Employment Service, 417

F.2d 569 (5th Cir. 1969), the court found an implied

right of action on behalf of migrant workers under an

obscure 1933 federal regulatory statute. There, as in

the case at bar, the defendant was a state agency functioning

under a federal regulatory scheme and receiving federal

grants in aid. The court held that the act's provisions

"conferred an interest" on the workers, and that the im

plied remedy of a private right of action was "imperatively"

called for in order to carry out the statutory purpose.

417 F .2d at 576. The court rejected the contention that

remedies to secure compliance with the statute could be

limited to federal administrative enforcement, stating:

"It is unthinkable that Congress, obviously

concerned with people, would have left the

Secretary with only the sanction of cutting

off funds to the state. Moreover, the

private civil remedy is a method of policy

enforcement long honored explicitly in

statutes and by implication with the help of

courts. Congress more and more commits to

individuals, acting as private Attorneys

General, the effectuation of public rights

through relief to individuals." (417 F.2d at

576)

The same reasoning impels recognition of the claim

under § 1455(c) here. That section is clearly intended

to confer an interest on all members of the class whose hous

ing opportunities are so vulnerable to the consequences of

-37-

Huntington's unlawful urban renewal actions. And these

persons are personally affected representatives of the

public interest, expressed in the Act's legislative his

tory, of preventing the spread of blight through the urban

renewal relocation requirement. To hold otherwise would

deprive the intended beneficiaries of federal projects of

a remedy for the violations of federal laws once the pro

ject is completed or once the federal funds have been used,

and thereby undermine the purpose of the Housing Act. While

an injunction against federal and local authorities from

carrying out an urban renewal project in violation of fed

eral law may be appropriate before the damage sought to be

enjoined has been done, see, e.g., Clark v. Romney, 321

F. Supp. 458 (S.D. N.Y. 1970), it is unrealistic to expect

that the persons affected will always be able to seek legal

redress at just the right moment. As in the present case,

24/their only remedy may be to seek redress for a past violation.

24/ In Norwalk CORE v. David Katz & Sons, Inc., 410 F.2d 532

(2d Cir. 1969), this Court was faced with the similar is

sue of whether a displacee from an urban renewal project

could enforce the federal relocation standards of § 1455(c)

against a private sponsor of the project. In this case, a

family sought to enjoin its eviction from a private housing

project on the grounds that the rent charged was higher than

permissible under federal standards. Because this Court

found that the rent charged was proper and the family had

been adequately relocated, however, it did not “pass upon

the question whether any or all of the private defendants have an obligation to assist in relocation of tenants in

a Project area" 410 F.2d at 535.

-38-

IV

The District Court Erred in Denying Injunctive

Relief On The Ground That The Prospective Dis- Placees Are Not Members Of The Class which Plaintiffs Represent

Although it is our position that the district court

erred in refusing to grant a preliminary injunction on the

basis of the record before it, it is clear that the denial

of plaintiffs' motion was based on the court's opinion that

the prospective displacees were not members of the class which

plaintiffs represent rather than on the merits of their claim.

The court did not appear to question plaintiffs' showing

as to the discriminatory effect of the Town's proposed action

upon those families who would be displaced from their homes

as a result. Rather, it was concerned only with whether

they had previously been displaced from the urban renewal

area (A. 143a-145a, 235a-236a). When it accepted the Town's

representation that none of the occupants of the four houses

that were the targets of code enforcement proceedings had

been displaced by urban renewal, it denied plaintiffs' motion

summarily. Thus, it held that plaintiffs were only entitled

to challenge the action of the Town on behalf of persons

previously displaced by the urban renewal project (A. 236a).

The court clearly erred in this ruling. The complaint

expressly defines the class on whose behalf plaintiffs sued

as "all the black and Puerto Rican residents of the Town

-39-

who are being and have been deprived of their rights to

equal housing opportunities by the actions of defendants"

(A. 3a). These actions are not limited to the execution of

the urban renewal project but include code enforcement,

restrictive zoning and opposition to public housing (A. 10a-16a).

Only the First Claim for Relief of the complaint is

specifically concerned with households displaced from the

urban renewal area (A. 4a-10a). Indeed, the Second Claim for

Relief seeks to enjoin the very conduct at issue here (A.

10a-13a).

As in Norwalk CORE, supra, plaintiffs have challenged

certain policies of a municipality because of their discriminatory

effect upon low income blacks and Puerto Ricans. Whereas in

Norwalk CORE the plaintiffs focused their attack on the

urban renewal project, plaintiffs here challenge a wider

range of public action. in each case, however, the allegations

that low—income blacks and Puerto Ricans are being deprived

of adequate housing raise questions that are common to the

entire class. Norwalk CORE, supra, 395 F.2d at 937.

The Court of appeals for the Ninth Circuit recently

recognized the propriety of a class action which, like the

present case, broadly challenged a municipality's housing

policies on behalf of low-income minority group residents.

Southern Alameda Spanish Speaking Organization v, City of

Union City, 424 F.2d 291, 295-96 (9th Cir. 1970). And in

-40-

ordering the city to "take steps necessary and reasonably

feasible under the law to accommodate within a reasonable

time the needs of low-income residents" on remand, the district

court granted relief with respect to the class that is very

similar to what plaintiffs seek here. Slip op. p. 21

2 5/(N.D. Cal. No. 51590, July 31, 1970).

Since all of the requirements of Rule 23 have been met

by the allegations of the complaint as well as by the proof,

difficult to understand the rationale upon which the

district court determined that the class which plaintiffs

represent was limited to the displacees from the urban

renewal area. in its July 2, 1970 memorandum opinion it

appeared to hold that the suit was maintainable generally as

a class action (A. 10a—11a), and no explanation for the

limitation was given during the hearing on plaintiffs' motion.

Such a limitation is tantamount to a dismissal of the major

part of the complaint and is clearly error. See Bui 1d nf

Buffalo, Inc, v. Sedita, ___ F.2d ___ (2d Cir. No. 34886,

April 13, 1971).

2_5/ The scope of the class in this case is similar to that in

employment discrimination cases where courts have recognized

the propriety of class actions which constitute an across the

board challenge to the discriminatory policies of an employer.

See Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 F.2d 1122 (5th Cir.

1969); Carr v. Conoco Plastics. Inc.. 423 F.2d 57 (5th Cir.

-41-

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment below

should be reversed and the case remanded to the district

court with directions to grant injunctive relief as prayed

for by plaintiffs. In the alternative, the case should be

remanded to the district court to make findings of fact

and conclusions of law on the merits of plaintiffs' claim.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack ''Greenberg

Jonathan Shapiro

Morris J. Bailer

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Sam R. Raskin

34 Dewey Street

Huntington, New York 11743

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appe1lants

2-