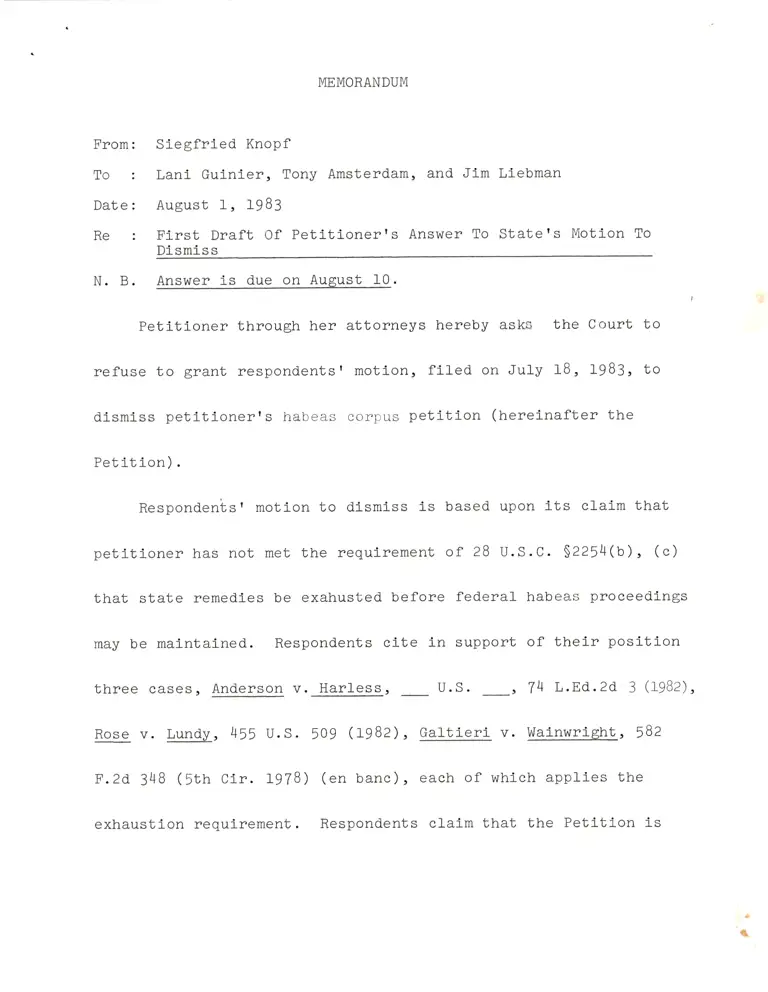

Memorandum from Knopf to Guinier, Amsterdam, and Liebman

Working File

August 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Memorandum from Knopf to Guinier, Amsterdam, and Liebman, 1983. 2f693b1e-ee92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/082680b2-23ac-4a6f-ba62-fc970f5d42c6/memorandum-from-knopf-to-guinier-amsterdam-and-liebman. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

From

To

Date

Re

N.B

MEMORANDUM

Siegfrled Knopf

Lanl Gulnler, Tony Amsterdam, and Jlm Llebman

August 1, 1983

Flrst Draft Of Petitionerts Answer To Statets Motion To

Dlsmiss

Answer is due on August 10.

Petitloner through her attorneys hereby asks the Court to

refuse to grant respondentsr motlon, f11ed on July 18,1983, to

dlsmiss petltlonerrs habeas corpus petitlon (herelnafter the

Petition).

Respondents I motion to dismiss ls based upon its claim that

petltioner has not met the requlrement of 28 U.S.C. $2254(b), (c)

that state remedles be exahusted before federal habeas proceedings

may be malntained. Respondents clte in support of their position

three cases, Anderson v. Harless,

-

U.S.

-,

74 L.Ed.2d 3 (1982),

Rose v. Lundy, 455 u.S. 509 (r98z), Galtieri v. Walnwrlght, 582

1'

F.2d 348 (5tn Cir. l-97B) (en banc), each of whlch applies the

exhaustlon requirement. Respondents claim that the Petition is

a

a rrmlxed petitionrr containing both

claims, and that, therefore, under

exhausted and unexhausted

Rose and Galtlerl it must be

dlsmlssed. In support, respondents c1alm, at

3 of their moti-on to di.smlss, that certain of

the bottom of page

the grounds in

petltionerr s habeas corpus petition rrhave never been presented

in the state courts of Alabamarrr and that other of the grounds

rrcontain claims

presented in the

the substance of which has [slc] never been fairly

state courts. rt

Petitioner decllnes to respond to the allegatlons that

certain of the claims in the Petltlon have not been previously

presented to the Alabama courts in a manner sufflclent to satlsfy

the exhaustion requlrement. Petiti.oner does so without admltting

these allegatlons or commentlng on them in any way. Petitioner

does so because she has satlsfled the exhaustion requlrements

sinee, applylng 28

of available State

U.S.C. S2254(b), r'there is either an absence

corrective process or the exlstence of clrcum-

stances rendering such process lneffective to protect [frer] rlghts.tt

It is, therefore, inapposite for the purposes of applylng the

-2-

exhaustion requlrements to the case at hand whether the clai-ms

in the Petltion have prevlously been pre-sented ln the Alabama

courts.

There are two procedures provlded under Alabama law for

obtalning post-conviction re11ef, the wrlt of error coram nobls,

and the writ of habeas corpus.

Alabamars common Iaw wrlt of error coram nobls i-s avai-l-able

only for challenges based on rran error of fact, one not appearing

on the face of the record and unknown to the court or the party

affected, and which, i-f known j-n tlme, would have prevented the

judgment challenged, and serves as a motion for a new trlal on

the ground of newly dlscovered evldence.rl Seibert v. State, 343

So.2d 7BB, 790 (afa. L977). The wrlt must be based on facts which

could not have been known at the tlme of trlaI. See, e.9., Ex parte

El]ison, 410 so.2d. 130 (A1a. 1982) While constltuti-onal challenges

have been allowed in the limited area of claims of ineffective

336 (AIa. 1978),assistance of counsel, Ex parte Summers, 366 So.2d

it i-s well establlshed that coram nobls rfdoes not 1le to enable

-3-

defendant to

279 AIa. 311,

question the merits of the case.rf Butler v. State,

184 so.2d Bzl Q966) ; see also Ex parte Vaughn,

395 So.2d 95 (A1a. 1979); Thomas v. State, 150 So.2d 383 (Ala.

1963); Edwards v. State, 150 So.2d 7l-l- (Ala. 1963); Ex parte

Banks, 178 So.2d 98 (ata. App. 1965)t Ex parte EII1s, t59 So.2d.

86Z (A1a. App. 1964). From the foregolng lt is clear that none

of the claims ln the Petltlon could have been consldered under

the Alabama wrlt of error coram nobis.

The Alabama wrlt of habeas corpus AIa. Code 515-21-1 et seq.

(1975), lssues only if the convlction attacked is void becuse it 1s

apparent on the face of the proceedings that the trlal court lacked

jurisdictlon to pronounce judgment Lee v. Lee, 160 So.2d 490

(ata. 1964); Edwards v. State, 150 So.2d 709 (A1a. 1963). Petltions

of the varj-ous constitutional rights grantedwhieh a11ege deprivatlon

to the accused

186 (A1a. crim.

physical abuse

734 (AIa.App.

are dismissed. See, e.9., Fields v. State, 40T So.2d

App. 1981) (Aueeing coerced. guilty p1ea, and other

in prrison); Shuttlesworth v.while

tg62) ,

Stater l5O So.2d

(AIa. 1963)cert. denied, 151 So.2d 783

(alleglng unconstltutionallty of

-4-

the penalizing statute); Ex parte

Thomas, 118 So.2d 738 (AIa . t960 ) , cert . denled sub nom, Thomas

v. Burford, 363 U.S. Bzz (1961) (a11eg1ng inter a1la denlal of

right to confrontation).

due to

tt rEven an allegation that a prlsonerrs

fallure to observe that fundamental fair-rri-ncarceration i-s

ness essential to every concept of justlcertwill not be sufflcierrtrt rr

rl

to obtaln the writ unl-ess the record shows the absence of jurls-

dlction by the convictlng court. Flelds v. State, 1+07 So . 2d 186 ,

187 (Ala. Crim. App.1981) (quoting, Postconvlction Remedles 1n

Alabama, 28 A1a. L. Rev. 6tT 623 (f978),(inner cltation omitted).

However, under Alabama law a clalm that the lndictment failed

each of the material elementsto a11ege that

of the offense

because such an

petltioner vlolated

charged 1s a clalm cognlzable 1n habeas corpus,

indlctment ls deemed vo1d. See, e.9., Barbee v.

State , 4l-T So.2d 611 (ata. Crlm.App.1982)

possible approaches to dealing wlth the limitedIf propose three

post-convlctlon revlew avallable for our indlctment clalms. Flrst,

in light of the argument below that parolees are excluded per se

from Alabama habeas, and since the State has not argued that the

r

indlctment c1aims are reviewable on State habeas, to not mention it--

1. e. , omit the paragraph above. Second, as paragraph 2l clearly

falls within the class of claims that are revlewable under Barbee,

to admit lt and show how the claim ln paragraph 2l has already

been exhausted. Third, to admit that paragraphs 19 and 21 may be

reviewed, and to rely on the parolee exclusion described below to

keep the petltlon exhausted.

not been rrfairly presentedt' ln

It ls clear that paragraph 19 has

the Alabama courts. But I belleve

there mlght be lmportant reasons for maklng this tradmissionrr wlth

regard to paragraph 19. An indictment whlch falls to a11ege prop-

erly the elements of the offense ls.vold under Alabama 1aw, and

is regarded as a claim which cannot be waived. See, e .gl. ,

cert. denied,Andrews v. State, 344 So.2d 533 (A1a. Crim. App.,

344 So.2d 538 (A1a. 1977). We face considerable Wainqlgh't v.

Sykes problems on the paragraph 19 clalm for both petitlons, and

the above argument could be quite useful in argulng that under

l

Alabama law there is slmply no procedural default.posslble with

regard to the paragraph lg cLaim. Thus, some of the reasons for

-6-

maklng this ttadmlssiontr are: 1) to ensure that we are consistent

in our characteri-zatlon of paragraph 19; 2) to attempt to get

the State to accept our characterizatlon of paragraph 19 before

the Sykes flght beglns; 3) torrcondltionttthe Court for our even-

tual argument on paragraph 19 vls a vls the issue of default. There

is no case on all fours wlth the issue of whether paragraph l-9

fits under the void lndictment rule 1n Alabama. However, I belleve

that a plauslble argument can be made that failure to a11ege 1n

the indlctment any of the elements of the various statutes charged

agai-nst petitloner in the instructlons, and the faet that those

statutes were 1n effect made elements of the $lZ-e3-f prohlbition

against tt any klnd of lIIegal . votingrrr constltutes rra defect

[1n the lndictment] assoclated with an essentlal element of the

offense." Andrews, .qlrp1.a,, at 534-535 (failure to allege the identity

of victlm in charge of assault rendered lndlctment void). l

[Alternatlve #2)

Therefore the clalm set forth ln paragraph 21 would be entltled

to review under Alabama habeas corpus, &S 1t charges that the

-T-

lndictment rrfailed to a11ege accurately each of the elements of

$17-23-1.'r But this claim has been rrfalrly presentedrrt Picard

v. Connor, 404 U.S. 270, 275 (1971), to the Alabama courts.

was raj-sed at petitionerts trla1, and at every step of the direct

appeal of the

under 28 U.S.

judgment against her, and as such 1t has been exhausted

C. $2254(b), (c); no state post-convlction review

i-s neces sary . See , e . B. r Brown v. All-en, 344 U.S. 4\7,447-448

(f953); Cronnon v. Alabama, 557 F.2d 472, \ll (5tn Cir. L977),

u.s. 974 (1979).cert. deniedr 440

In peti-tionerts plea the indictment Was attacked on numerous

grounds, lncluding, ln plea number 2, that rrthe indi-ctment fails

to state an offense under the laws of the State of Alabafl&rttand,

in plea number 3, that the lndictment rffails to reasonably apprise [sicJ

to defendrrr lnthe defendant of what 1t is she is

viol-ation of the Due Process Clause

cal1ed upon

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

At least once during her triaI, petitionerrs counsel renewed all

of the objectlons ralsed in her p1ea. Tr. 220-- WlIder.

Before the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals petltloner again

It

-uF

made vari-ous obj ections to the indlctment. She charged in the

brlef filed on her behalf in the Al-abama Court of Crlminal Appeals

that she was denied due process as guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment by the fail-ure of the indictment to advlse her of what

she was call-ed on to defend. See Respondentsf

Exhlblt t'Brr at 25-29. The brlef charged that "[t]he indictment

simply followed the language of the statute,rrbut that't[t]he leg-

lslature failed in the statutes at issue to set forth the el-ements of the

crime. rr Id at 26. It was then argued, clting lnter ali-a,

Russell v. United States, 369 u.s. 7\9 0962) (mlsclted in the

brief as rrhrssell v. Staterr), that fthe lndictment must contain

the elements of the offense lntended to be charged and sufflciently

apprlse the defendant of what he must be prepared to meet.rt Id.

Given the premise of her argument, that the indlctment traced the

not state each of thelanguage of the statute whlch itself dld

elements of the offense, petltloner made out a clear objectlon

to the indlctment

that each element of

i.e., that lt dld not conform to the requlrement

the offense be charged.

-9-

Subsequently, the

brlef specified that it is the rralternative charger or

or fraudently voterrr whlch fa11s to state an

elements of the offense

the Court rejected that

dld

offense.i11ega11y

Id. at 29. Since $f7-e3-l proscribes "any kind of iI1ega1 or

part of thefraudulent votingrr the brief thus pinpoints that

charge where tracki-ng the language of the statute resul-ts 1n

an indictment which fall-s to a11ege each element of offense.

Also slnce Russell tles a number of rul-es for the indlctment,

includlng the requirement that each element of the offense be

accurately charged, to the Slxth Amendmentrs Notice Clause,

369 U.S. at 760-761, and to "baslc prlnclples of fundamental

fairness." Id. at 765-766, 1t is clear that petltionerrs argument

was hi-nged on the same basic constltutional rights rel1ed on in

the Petltlon.

The Court of Crlminal Appeals dealt wlth all of petltlonerrs

objectlons to the indictment 1n part II of lts opinion. The Court

recognlzed that petltioner argued that the lndlctment rrfailed to

charge an offense ,tt 4Of So.2d at 160. But, having deflned the

at 159-160,

the others

earlier ln the oplnion, fd.

objection along wlth all of

-10-

petitioner had levied agalnst thelndlctment, Id. at 160-161.

Petltioner, 1n her brlef requesting a rehearlng before the

Alabama Court of Crlminal Appeals, Respondent I s Exhibit ltErr aE

5-6, and 1n her brlef 1n support of her Petition for Wrlt of

Certlorarl in the Alabama Supreme Court, Respondent I s Exhibit rrFrr

at 31-33, ostensibly restated the arguments agalnst the lndlctment

made in her initial brief to the Court of Crimina1 Appeals.

The claim presented in paragraph 2l is the rrsubstantlal equlva-

lentrttPlcard v. Connor, supra at 278, of the clalm petltloner

presented to the State courts. Both claims rely for 1ega1 support

of the Fourteenth Amendment. Both clalms

charge an

one whlch

against petitloner

element of the offense, and that the omltted

on the Due Process Clause

assert that the lndictment fa11ed to

element ls

is not explicitly stated 1n

assertlon that the statute

the statute. fn both cla1ms, the

falIed to set forth each of the elements

of the crlme

ttany kind of

is focused on that part of the statute whlch proscribes

111egal or fraudulent votlngrrt and 1t 1s then alleged

i-n each claim that the State dld not cure that failure in its

-11-

thdictment against petltloner. In order to satlsfy the

exhaustlon requlrement it 1s not necessary that the claim

raised 1n the State courtsItspell out each syllablerrof the

federal claim. Lambert v. Wainwrlght, 573 F.2d 277, 282 (5tfr Cir'

7975). The Alabama State courts have prevlously been given a falr

and adequate opportunity to pass upon the trsubstantlal equivaleotr"

id., of the c1a1m put forth ln paragraph 2l-.

[Alternative #3, (one paragraph only)]

Therefore, the clalms stated in paragraphs 19 and 2l of the

petition would be entltled to revlew under Alabama habeas corpus.

Each of these clalms alJ,eges that the lndictment failed to charge

certaln cruclal elements of the offense brought to bear agalnst

petltioner.

None of petitlonerrs other clalms alleges what amounts

to a vold judgment under Alabama 1aw, and thus none of those cl-alms

can be heard on State habeas corpus.

Even though (one) (two) of her cla1ms may be heard under

Alabama habeas corpus, petltloner ls completely fo#tosea from

-l-2-

uslng the post-convlction relief process in Alabama because of

her status as a parolee. In Wllliams v. State, 155 So.2d 322

(AIa. App.) cert. qq4i9g, l55 So.2d 323 (A]a. 1963), it was held

that tt[h]abeas corpus is not a state court remedy available to a

parolee

Id. at

ln Alabama, who ls not otherwlse under detentionrrf

323. Parole was designated. in Wi111ams as t'[m]ere moral

restraint as distlnguished from actual conflnement.rr Id.

(quoting Jones, J., Habeas Corpus, State and Federal, The AIa.+'

Law. Oct. 7952, p, 3841.

(AIa. Cr. App. l992)r where

v. McCurley , 4L2 So.2d 1233

in the midst of a five

was granted the wrlt.

[eut cf State

petltioner ,

year term of probation,

" Ig]enerally,

The court stated that

the writ of habeas corpus is not available to persons

not ln custody such

is prospective on1y.

as on parole or bail, oP where the sentence

may issue agalnst

of j urisdictlon. rr

aIla Williams] However, a writ

a judgment which is void on

Id. at 1234. Note that the

Iclting inter

of habeas corpus

its face for

way these two

wont

sentences are constructed the second appears to state

-13_

an exceptlon to the rule stated in the flrst. But under any

circumstances habeas 1s available only against judgment of the sort

descrlbed 1n the second sentence. Therefore, if the second were

an exception to flrst 1t would render the rule of the flrst totally

meanlngless, whlch the oplnlon does not purport to do. In W1l1iams

the Court of Appeals dld not even mentj.on the grounds for the

petitlon; all conslderation was foreclosed by the petitionerrs

parolee status. Also with dlctum arguably contrary to Wi111ams

is Palmer v. State, 52 So.271 (AIa. 1910) where the court ln deny-

ing standing to a petitloner released on ball to maintain a

habeas actlon stated that in order to bring a habeas action the

petltlonerrrmust be 1n such control or custody of the person against

whom the petitioner is directed that hls body can be produced at the

hearlng by the sald custodlan or restralner. . actual confinement

in Ja11 ls unnecessary.rr Id. at 271-272. Applylng thls language

from Palmer, a parolee is under sufflclent restralnt to brlng a

habeas acti-on. Nonetheless W1l-l-iams has never been overruled or

even critieized, but no other case can be found deallng with the

-14-

standlng of a parolee to malntaln a State post-convlctlon actlon. l

Thus parolees are exp11c1ty prevented from malntalnlng State habeas

challenges.

Wh11e no Alabama case deals wlth the standlng of a parolee to

malntaln a coram nobls actlon, there 1s no reason to belleve the

W1l11ams rule would not control. If a Judgment vold on 1ts face can-

not be challenged by a parolee, there ls no reason to suspect that

parolees would be glven access to the post-convlctlon process to

challenge the merely voldabl_e Judgments that are subJect to revlew

a parolee couldunder coram nobls. It ls merely conJectural that

malntaln a coram nobls actlon, and for that reason alone petltloner

need not attempt to pursue the wrlt of error coram nobls ln order

to exhaust State remedles under, e.8., Wllwordlng v. Swenson, 404

u.s. 249, 250 (1971).

Concluslon

Respondents? motlon to dlsmlss the cause should be denled.

-1 tr-