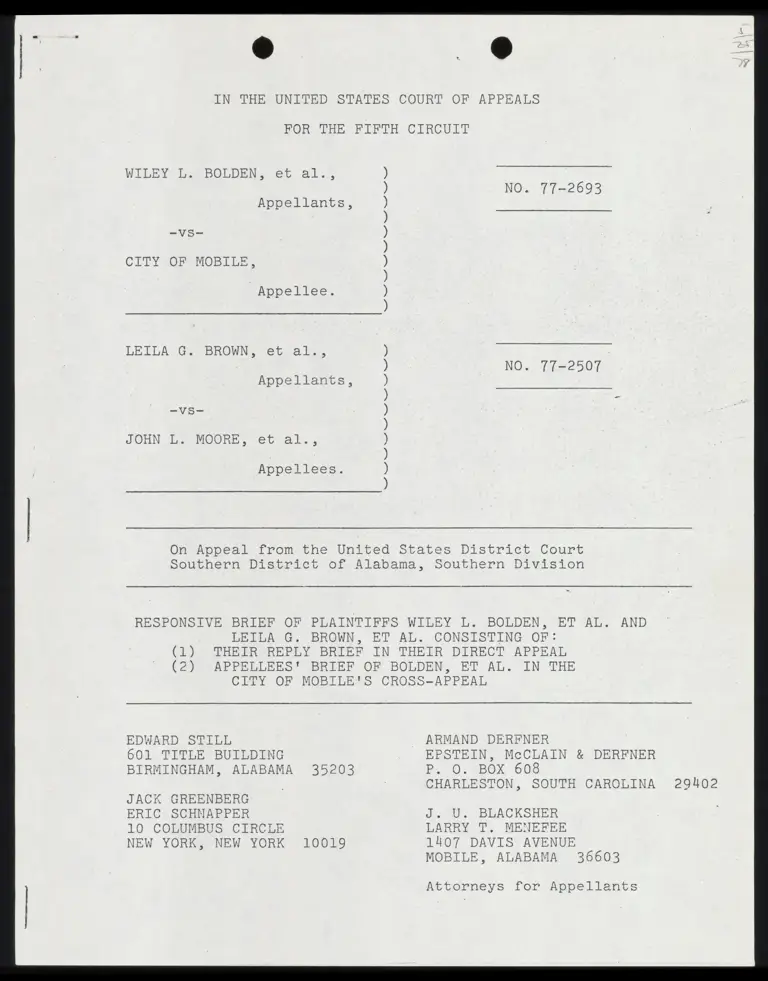

Responsive Brief of Plaintiffs Bolden and Brown

Public Court Documents

May 25, 1978

11 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Responsive Brief of Plaintiffs Bolden and Brown, 1978. 301116eb-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/083cb8ce-3b79-4244-b490-40f17ca22875/responsive-brief-of-plaintiffs-bolden-and-brown. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

WILEY L.~BOLDEN, et al.,

)

) NO. 77-2693

Appellants, )

)

-VS— )

)

CITY OF MOBILE, )

)

Appellee. )

)

1.EILA GCG. - BROWN, et.-al.,

NO. 77-2507

Appellants,

JOHN L. MOORE, et al.,

Appellees.

S

r

N

o

S

e

N

n

N

N

N

F

a

S

N

N

A

5

On Appeal from the United States District Court

Southern District of Alabama, Southern Division

RESPONSIVE BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS WILEY L. BOLDEN, ET AL. AND

LEILA G. BROWN, ET AL. CONSISTING OF:

1) THEIR REPLY BRIEF IN THEIR DIRECT APPEAL

2) “APPELLEES! BRIEF OF BOLDEN, ET Al. IN THE

CITY OF MOBILE'S CROSS-APPEAL

(

(

EDWARD STILL ~~ ARMAND DERFNER

601 TITLE BUILDING EPSTEIN, McCLAIN & DERFNER

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA 35203 P. 0. BOY 608

CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA 29.402

JACK GREENBERG

ERIC SCHNAPPER J. U. BLACKSHER

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE LARRY T. MENEFEE

NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 1407 DAVIS AVENUE

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36603

Attorneys for Appellants

| :

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

)

) NO. 77-2693

Appellants, ) ; 4

)

-VS- )

)

CITY OF MOBILE, )

)

Appellee. )

) mp

LEILA BG. BROWN, ef al., i

NO. 77-2507

Appellants,

JOHN L. MOORE, et al.,

Appellees.

N

a

?

M

e

N

a

?

M

d

No

s?

N

o

No

ut

?

N

u

t

N

a

’

“

a

t

On Appeal from the United States District Court

Southern District of Alabama, Southern Division

RESPONSIVE BRIEF -OF PLAINTIFFS WILEY L. BOLDEN, ET AL. AND

LEILA G. BROWN, ET AL. CONSISTING OF:

(1) THEIR REPLY BRIEF IN THEIR DIRECT APPEAL

(2) APPELLEES' BRIEF OF BOLDEN, ET AL. IN THE

CITY OF MOBILE'S CROSS-APPEAL

: ¢ . L

This brief is filed by plaintiffs Bolden, et al.,

and Brown, et al., as a (1) reply brief in their consolidated

appeals, and (2) an appellees’ brief for Bolden, et al., in the

cross-appeal filed by the City of ot ve

These appeals involve landmark voting rights litiga-

tion. Especially with respect to the City case, where the relief

sought and obtained (voiding at-large elections in a "commission"

form of government) was unprecedented, the litigation has been

extraordinarily novel, complex, unpopular, and--most of all--

highly contingent.

The direct appeal involves plaintiffs! claim that the

fee awarded was inadequate because the district court--while

making favorable findings on many of the Johnson v.>Georgia High-

way Express standards, especially contingency and excellence of

results--ailed to raise the lodestar rate to reflect these favo-

rable findings.

The cross-appeal involves defendant City of Mobile's

claim that the fee awarded was excessive because the district court

failed to compute the hours or lodestar rate properly and because

the court erroneously included out-of-pocket expenses in the award,

Direct Appeal

Both Congress and this Court have recognized the impor-

tance of compensating attorneys for the risk of litigation, or

1/ | No cross-appeal was filed in Brown v, Moore (the Board

of School Commissioners case).

® >.

contingency. Congress has done so in the legislative history

of the 1976 Fee Act by explicitly citing with approval several

cases in which courts have raised hourly rates to compensate

for the risk of litigation and results athe ins by

using fees in antitrust cases as the benchmark for civil rights

fees. This Court has done so chiefly in Yolf v. Frank, 555 F.2d

1213 (5th Cir. 1977), where the same factors led to a one-third

erihaticehent of already-high hourly rates. The Teetsiative his-

tory and cases are discussed in detail in our main brief at pp.

22-26, and are not answered in the defendants' briefs,

Instead the defendants apparently rely chielly on the

testimony of their lawyer witnesses. A short look at that testi-

mony is instructive.

The defendants put on five Mobile attorneys as witnesses.

Each one said what he thought plaintiffs' attorneys' work was

worth, but the testimony given by each witness revealed the very

slender and subjective basis of his estimate. Mr, Pipes testified

that he thought the work was worth en Son he conceded that

his own rates ranged from $50-100 per hour, and he displayed no

familiarity with these particular cases. Tr. 66-76. Mr. Reed

and Mr. Engel both recommended $50-30 per hour; each one was asked

whether he had considered the contingent nature of the case in

arriving at his recommended fee, and each replied, in virtually

2/ E.g., Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 8 EPD § 94u}

(C.D. Cal. 1974); Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D.

680 (N.D, Cal. 1974).

3/ In each set of figures, the higher one is for the time

of Blacksher and Still, while the lower figure is for

the other attorneys.

. a J

identical language, thet he didn't see much contingency because

he thought it was a "foregone conclusion" from the outset that

plaintiffs would win! Tr. 85, 908, 104. As Mr. Reed put it,

"to be perfectly frank, I thought this case was a laydown."

Tr. 85. Mr. Matranga also selected the figure of $50-30 and

apparently thought there was no contingency because the fees

would be paid regardless of the outcome. Tr. O04. “Pinally, Mr.

Thornton selected the breathtaking rates of $35-20 per hour, and

capped the hearing by suggesting that contingency might be a

basis for awarding lower than prevailing rates. Tr. 112.

Most notably, there is no indication that any of the

defendants' attorney witnesses ever adequately considered the

impact of contingency or the risk of litigation in setting a fair

fee. Indeed, there is no indication in the record that any of

the defendants! witnesses actually does any appreciable amount of

work that is not fee-guaranteed. And while many of the defendants’

witnesses have had extensive experience in defending against civil

rights claims (for guaranteed fees or on regular retainers), there

is nothing in any of thelr testimony to indicate that any of them

has ever represented a civil rights claimant. In short, these

witnesses represent an entirely different spectrum of the legal

world, and their testimony as to an appropriate fee bears no re-

lationship to the problem addressed by Congress and this Court:

how to set Tees which will attract counsel to enforce the federal

civil rights laws.

We agree that the purpose of court-awarded attorneys

fees is not to make lawyers rich but is to provide fees healthy

enough to attract and fairly compensate first-rate counsel. Will

the fees awarded here do that job? In these two cases, plain--

tiffs' counsel spent more than 1,500 hours from mid-1975 to late

1976. Neither case is yet over. At this time, plaintiffs have

won a far-reaching judgment in the City case, which has been af-

firmed by this Court but which is virtually certain to be taken

to the Supreme Court; plaintiffs have also won the Board of School

Commissioners case, which is still pending on appeal in this

Court. Litigation on the merits will almost certainly last into

1979, which means that if plaintiffs ultimately win; the attorneys

will be pald in 1969 or 1980. If plaintiffs lose, the attorneys

will get nothing, except for negligible overhead contritubions

made by two organizations. In other words, for the privilege of

waiting three or four years to see if they would be paid at all

for devoting (collectively) nearly a year's worth of lawyers!

time, plaintiffs' attorneys are to be paid (if successful) the

same rate (and a far lower total) than they would have received,

day in-day out, for representing the defendants. We simply do

not believe that civil rights cases will make their own way, as

Congress intended, under these circumstances.

Cross-Appeal

The City of Mobile also cross-—appeals, on three grounds:

1. The district court erred in failing to de-

duct time that the cross-appellant claims

was duplicative.

2. The district court erred in failing to reduce

the hourly rate below that received by counsel

miCE AE

for the City of Mobile,

3. The district court erred in awarding out-

of-pocket expenses which do not fall in the

category of traditionally taxable costs.

The answers to these three claims are simple:

is There was no error in the court's factual computa-

tion of time expended.

The district court's time computations are findings of

fact, which cannot be overturned without a showing of clear error.

Far from making such a showing, defendants concede that "the City

did not challenge before the district court the accuracy of the

time records submitted by Plaintiffs’ attorneys." Mobile brief,

pp. 15-16. Nonetheless, Mobile now claims that many of plaintiffs?

attorneys' hours were wasted and that others were spent on non-legea

work.

The proper forum for defendants' claims was in the dis-—

trict court. Although defendants had the full opportunity to

support their claims in the district court, they presented no evi-

dence nor cross-examination to substantiate the claims. Having

failed to persuade the district court that plaintiffs’ attorneys!

hours should be reduced, the defendants' invitation to this Court

to roam again through the records must be rejected.

2. The district court was correct in finding that the

rate paid to Mobile's own attorneys was a fair lodestar rate.

While plaintiffs have claimed in their direct appeal

that the lodestar rate should have been increased by the district

court because of contingency and other factors, we do not claim

error in the district court's factual finding of the lodestar rate.

* 5

The City of Mobile, on the other hand, does dispute the district

court's establishment of the lodestar rate at $50 per hour--the

rate paid by the City to its own attorneys. As plaintiffs under-

stand Mobile's argument, the City claims that the district court

erred in finding that the rate paid to the City's attorneys iss

the customary rate in the area for work of this type. Plaintiffs

are at a loss to understand how a party (especially a governmental

body) can pay its attorney at a certain rate and simultaneously

5/

claim that the prevailing local rate 1 actually a lower figure.

A rational person should be entitled to think that the rate paid

by one party to its lawyer is at least good enough evidence of the

prevailing rate to support a factual finding to that effect. Com—

pare Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 66 F.R.D.

483 (W.D.N.C. 1974). As we have noted in our direct appeal, the

use of equal hourly rates still gave the City's attorneys a fee

for losing which was half again as much as the plaintiffs were

hy The City also quarreled with the rate pald to plaintiffs’

younger attorneys, notwithstanding that the City itself

was paying $50 per hour to its law firms youngest attorneys. In

any event, courts have consistently recognized that an attorney's

skill and efficiency are not necessarily measured by his years.

Cape Cod Food Products, Inc. v. National Cranberry Association,

119 P. Supp. 242 (D. Mass. 1954); Wallace v. House, 377 PF. Supp.

1192, 1208 (W.D. La. 197%).

5/ Mobile apparently wishes to lock the district court

rigidly into a finding that the prevailing rate for

cases like this "is" $40 per hour. In fact, the district court

made a rather loose finding that the prevailing rate "hovers near"

that rate. This language surely reflects the court's recognition

that rates paid by public bodies varied somewhat rather than being

uniform. Indeed, of the public bodies in these three companion

cases, only one (Board of School Commissioners) paid its attorney

. $40 per hour; the other two (City of Mobile and County Commissioners)

both paid their attorneys $50 per hour. Appellants! main brief,

vp. 9: Tr. "783, 96,113.

awarded. Reducing plaintiffs' rate to $40 per hour, as Mobile

urges, would give them a fee barely one-half that of defendants,

and would go that much further toward breaking Congress' promise

of attracting competent counsel to civil rights cases,

3. The fee statutes authorize payment of out-of-pocket

expenses.

The City of Mobile argues that the district court was

unauthorized to award out-of-pocket expenses because they are not

attorneys' fees and because there is no explicit statutory language

providing for such payments. This argument ignores the purpose of

the fee statutes, the legislative history, and the tradition de-

veloped in countless cases.

The purpose of the statute was to remove the burden of

litigation from civil wvights plaintiffs; in order to do so, Yeiti-

zens must have the opportunity to recover what it costs them to

windicate these rights in court.Y 8S REP. NO. 1011, 94th Cong. 24

Sess. ,.at 2 (1976). Moreover, Rep. Drinan, the House floor manager,

said specifically that the phrase attorneys! fee includes "all in-

cidental and necessary expenses incurred in furnishing effective

and competent representation. 122 CONG. REC. H12160 (daily ed.

Oct. 1,:3976).

Finally, this Court and other courts, including the

Supreme Court, have traditionally viewed out-of-pocket expenses

as part of attorneys' fees and have awarded them where attorneys"

fees were authorized. Fairley v. Patterson, 493 7.24 598, 607

{(5chiCir. 1974); Bradley v.. School Board, 53 P.R.D. 28 (£.D. Va.

1971), aff'd, 416 U.S. 697 (1974); Sims v. Amos, 340 PF. Supp.

;

. ®

691 (M.D. Ala. 1972), aff'd, 409-U.8, Qu? £1972); Davis v. County

of los Angeles, 8 E.P.D, 9 9hid (C.D, Cal. 1974); Stanford Daily

v. Zurchey, 64 P.R.D., 680 (N.D. Cal. 1974), aff'd, 550 P.24 464

(9th Cir. 1977), cert. granted.

CONCLUSION

Por the reasons stated herein and in our main brief,

this Court should rule against the cross-appeal, but should sus-

tain the direct appeal and remand these cases to the district

court for an upward revision of the attorneys' fee awards.

Respectfully submitted, ..-

L., aud 1S ett Lik,

ARMAND DERFNER |

Epstein, McClain & nehios

P..0, Box 608

Charleston, South Carolina 29402

(803) 577-3170

J. U, BLACKSHER

Crawford, Blacksher, Figures & Brown

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama. 36603

(205) 423-1691

EDWARD STILL

601 Title Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

(205) 322-1694

JACK GREENBERG

ERIC SCHNAPPER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

May 25, 1978.

WE

i #

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that I have mailed two copies of Responsive

Briel of Plaintiffs Wiley L. Bolden, eft al. and Leila G. Brown, -

et al., consisting of (1) their Reply Brief in their direct

appeal, and (2) their Appellees' Brief in the City of Mobile's

Cross—-Appeal, and two copies of the Record Excerpts, to

William C. Tidwell, 111, Esq., Hand, Arendall, Bedsole, Greaves

& Johnson, 300 First National Bank Bldg., Mobile, Alabama 36602,

counsel for appellees in No. 77-2693, and two copies of each to

Robert C. Campbell, 111, Esqg., Sintz, Pike, Campbell & Duke,

Plaza West Building, 800 Downtowner Blvd., Mobile, Alabama 36609,

counsel for appellees in No. 77-2507.

1 Q

May 25, 1978 ATE Wn

ARMAND DERFNER I