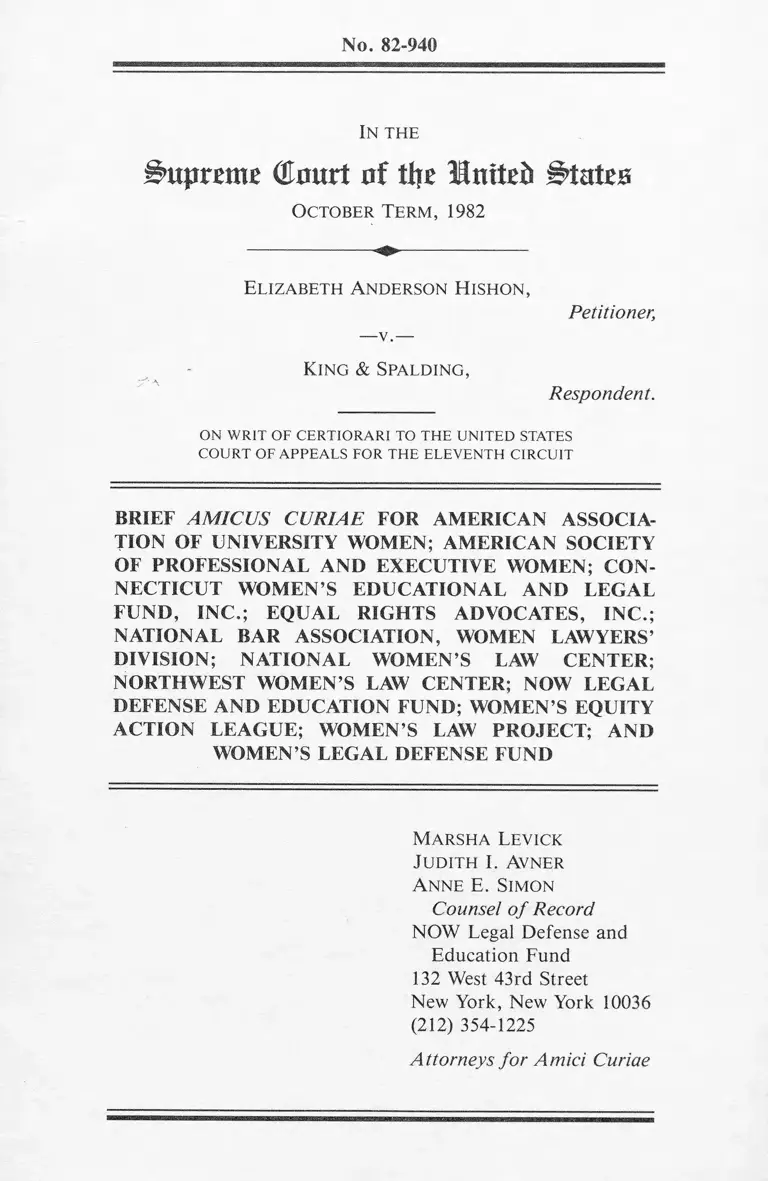

Hishon v. King & Spalding Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hishon v. King & Spalding Brief Amicus Curiae, 1982. edf1fc42-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/08aa5901-ede7-43b7-8212-6dc956132f13/hishon-v-king-spalding-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

No. 82-940

In the

Supreme (Enurt of tire United States

October Term , 1982

Elizabeth Anderson H ishon,

Petitioner,

King & Spalding,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF AM IC U S CU RIAE FOR AMERICAN ASSOCIA

TION OF UNIVERSITY WOMEN; AMERICAN SOCIETY

OF PROFESSIONAL AND EXECUTIVE WOMEN; CON

NECTICUT WOMEN’S EDUCATIONAL AND LEGAL

FUND, INC.; EQUAL RIGHTS ADVOCATES, INC.;

NATIONAL BAR ASSOCIATION, WOMEN LAWYERS’

DIVISION; NATIONAL WOMEN’S LAW CENTER;

NORTHWEST WOMEN’S LAW CENTER; NOW LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND; WOMEN’S EQUITY

ACTION LEAGUE; WOMEN’S LAW PROJECT; AND

WOMEN’S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

Marsha Levick

Judith I. Avner

Anne E. Simon

Counsel o f Record

NOW Legal Defense and

Education Fund

132 West 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

(212) 354-1225

Attorneys fo r Am ici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Authorities..............

Interest of Amici Curiae.........

Statement of the Case.............

Summary of Argument...............

Argument

I. THE DECISION BELOW WOULD UNDER

MINE THE SUBSTANTIAL PROGRESS

WOMEN HAVE MADE TOWARDS ACHIEV

ING EQUALITY OF EMPLOYMENT OP

PORTUNITY IN THE LEGAL PRO

FESSION......................

II. THE LOWER COURT'S VIEW THAT

THE PARTNERSHIP FORM MANDATES

EXEMPTION OF SOME PARTNERSHIP

DECISIONS FROM TITLE VII IS

ERRONEOUS....................

A. The Eleventh Circuit's

Decision is Based on an

Idealized and Inaccurate

View of "Partnerships"•••

B. The Eleventh Circuit Er

roneously Construed Title

VII by Focusing on Formal

Differences and Ignoring

Functional Similarities

Between Corporate and Part

nership Forms of Organization

in Professional Services

Businesses ................

iii

1

2

3

Page

19

20

28

x

Page

III. DECISIONS ON ADMISSION TO PART

NERSHIP ARE EMPLOYMENT DECISIONS

SUBJECT TO SCRUTINY UNDER TITLE

VII........................... 36

A. The Termination of Employment

as the Result of an "Up or

Out" Policy is an Employment

Decision Under Title VII. 36

B. Progression from Associate

to Partner is Clearly an

Expectation of Employment

as an Associate. 40

C. Partnership Decisions are

Not Protected by the Free

dom of Association....... 45

IV. TITLE VII’S APPLICATION TO PART

NERSHIPS AFFECTS MANY IMPORTANT

SECTORS OF THE ECONOMY, NOT

SIMPLY LAW FIRMS.... 54

CONCLUSION................ 64

APPENDIX

- ii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422

U.S. 405 (1975) ........... 5,44

Beilis v. United States, 417 U.S.

85 (1974)....................... 54

Blank v. Sullivan & Cromwell. 418

F. Supp. 1 (S.D.N.Y. 1975)....... 15

Bradwell v, Illinois, 83 U.S. (16

Wall) 1308 (1873)............... 6

Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1

71*976)........................... 51

Citizens Against Rent Control/

Coalition for Fair Housing v.

City of Berkeley, 454 U.S.

290 (1981)...................... 47

CSC v. Nat'1 Assoc, of Letter

Carriers, 413 U.S. 548 (1973)-.. 5,51

First Bank & Trust Co. v. Zagoria,

51 U.S.L.W. 2529 (Ga. Feb. 23,

1983)............................ 33

Gilmore v. Kansas City Terminal

Railway Co., 509 F.2d 48"(8th

Cir. 1975JT..................... 44

Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc, v.

United States, 379 U.S. 241

(1964)........................... 49,50

iii -

Hishon v . King & Spalding, 678 F.

2d~T02T'"(11th Clr7l9S?)....... in passim

In re Primus, 436 U.S. 412 (1978). 52

Page

Kohn v. Royal1, Koegel & Wells,

59 F.R.I., 515, tS.D.N.Y. 1973)

appeal dism., 496 F.2d 1094

(2nd Cir. 1974) .................. 14

Kunda v. Muhlenberg College, 621

F . 2d 532 (3d Cir. “1980)........ 38

Lieberman v. Gant, 630 F.2d 60

(2d Cir. I980T . ................ 38

Lucido v. Cravath, Swaine & Moore,

425 F. Supp. 123 (S.D.N.Y.

1977)......................... .4,37,45,62

NAACP v. Alabama ex rel Patterson,

357 U.S. 449 (1958)............ 48

NLRB v. Yeshiva University, 444

U.S. 672 (T9^oyT7TT 77.'. ......... 39

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455

CI9 73) .7772 . .777.............. 5,47,48,49

Ohralik v. Ohio State Bar Ass'n,

436 U.S. 447 (1978)~.... 53

iv

Page

Payne v. Travenol Labs, 673 F.

798 (5th"Cir. 1982), cert,

den., 74 L.Ed. 2d 605 (1983J--- 44

Pinckney v. County of Northhampton,

512 F. Supp. 989 (E.D. Pa. 1981),

aff'd., 681 F .2d 808 (3rd Cir.

T982)............................ 44

Railway Mail Ass'n v. Corsi, 326

U.S. 88 (1945)................. 50

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160

(1976).................. .48,49,50

Sweeney v. Bd. of Trustees of Keene

State College, 569 F.2d 169 (1st

Cir.), vacated and remanded on

other grounds, 439 U.S. 24 (1978),

605~F.2d 106 (1st Cir. 1979)____ 44

United States Department of

Agriculture v. Moreno, 413 U.S.

528 (1973)...................... 47

U.S. Postal Service Bd. of

Governors v. Aikens, 51 U .S .L .W .

4354 (TIT'S. Apr. 4, 1983)......... 44

Village of Belle Terre v. Boraas,

“ 416 U.S. 1"TT974)............- • • 46

Widinar v. Vincent, 454 U.S. 263

( M U . ___7777................. 47

v

Books, Newspapers, Periodicals

& Studies

American Women’s Society of

Certified Public Accountants,

A 1981 Statistical Profile of

the Woman Certified Public

Accountant "(1981)..............

Blum, Professional Incorporation:

Social Change Created by the

Tax Act, 14 Taxes~51 (1982)...

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S.

Dept, of Labor, Employment and

Earnings--Household Data Annual

Averages (Jan. 1983)...........

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S.

Dept, of Labor, The Female-Male

Earning Gap: A Review of Employment

and Earnings Issues (Sept. 1982). 57

C. Epstein, Women in Law (1981)...in passim

Flaherty, Women and Minorities: The

Gains, National Law Journal, Dec.

20, 1982.......................... 14,16

Glancy, Women in Law: The Dependable

Ones, 21 Harv. L.S. Bull. No. 5

(June 1970)...................... 12,16

Greer, Women in Architecture A

Progress (T ) Report and a

Statistical Profile, AIA Journal,

Jan7 1982, at 40................. 57,61

Hochberger, Women in Law--How Far

Have They Come? Mew York Law

Journal, Mar. 21, 1977.......... 13

58,60

29,30

8

Page

vi

Page

P. Hoffman, Lions in the Street

( 1973) ............................................................... 23, 36, 37,40

Internal Revenue Service, Dept,

of Treasury, Statistics of

Income-1978 Partnership Returns

(1982).................. 55

Internal Revenue Service, Dept. of

Treasury, Statistics of Income-

1979 Partnership Returns (1982).. 55

Internal Revenue Service, Dept, of

Treasury, Statistics of Income-

1980 Partnership Returns 71982)..54,55,56

Ms. CPA, Forbes, Aug. 17, 1981,

at 8.............................. 58,59

National Laxtf Journal, Apr. 25,

1983, at 9, Col. 1 ................ 25

National Law Journal, Cct. 6,

1980.............................. 21

Nelson, Practice and Privilege:

Social Change and the Structure

of Large Law Firms, 1981 Amer.

Bar Fdn. Research J. 97......... 24,36,41

Orren, A Look Inside Those Big

Firms, 59 A.B.A.J. 778“TT973)___ 27

Raggi, An Independent Right to

Freedom of Association, 12 Harv.

C.R.-C.L.L. Rev. 1 (1977)........ 46

Vll

Rank, More Women Moving into Public

Accounting, But Few to the~Top~

New York Times, Dec. 17, 1977,

at B18, Col. 1 .................. 58

Smigel, The Wall Street Lawyer

(1963) ...................... . .24,36,40,42

Society of Women Engineers, A Profile

of the Women Engineer (1982)7.77 60

M. Stevens, The Big Eight

(1981)..... ...... 77. . .---- 22,26,27,43,59

J. Stewart, The Partners (1983)... 23,37,43

Tribe, American Constitutional Law

(1978)7 ..... 7777777777777777777 46

wayne, The Year of the Accountant,

New York Times, Jan. 3, 1982,

at D1, Col. 1 ................... 22

Wood, The Desirability of Professional

Corporations after the Economic -

Recovery Tax Act, 60“Taxes“261“

098717777777777................ 30

Young & Herbert, Political Association

under the Burger Court: Fading

Protection, 15 U. Cal. Davis L.

Rev. “53 (T981).................. 46

viii

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. §2000e et seq........... in passim

Ga. Code J14-7-5(a) (1982)....... 33

Ga. Code §14-7-7 (1982).......... 32

H. Rep. No. 760, 97th Cong.,

2d Sess. 621 (1982)............. 31

H. Rep. No. 760, 97th Cong.,

2d Sess . 634 (1982)............. 34,35

N.Y. Bus. Corp. Law §1507

(McKinney Supp. 1982)........... 33

N.Y. Bus. Corp. Law §1511

(McKinney Supp. 1982)........... 33

N.Y. Bus. Corp. Law §1505(a)

(McKinney Supp. 1982)........... 32

1982 U.S. Tax Week 1973 .......... 31,32

S. Rep. No. 494, 97th Cong.,

2d Sess. 314 (1982)............. 30

26 U.S.C.A. §331(a) (West Supp.

1983)............................ 34

26 U.S.C.A. §1001 (West 1982).... 34

118 Cong. Rec. 3802 (1972)....... 17,18

Codes & Statutes Page

- ix -

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

This brief amicus curiae in support of

petitioner is submitted on behalf of the

American Association of University Women;

American Society of Professional and Execu

tive Women; Connecticut Women's Educational

and Legal Fund, Inc.; Equal Rights Advocates,

Inc.; National Bar Association, Women's Law

yers Division; National WTomen' s Law Center;

Northwest Women's Law Center; NOW Legal De

fense and Education Fund; Women's Equity

Action League; Women's Law Project; and

Women's Legal Defense Fund.- These organi

zations are dedicated to the principle of

equal treatment under the law and to the

elimination of sex and race discrimination

/V/V j

in e m p l o y m e n t ' Amici believe that this

case is of great importance for the full ef

fectuation of Title VII's mandate to elimi

nate employment discrimination.

rcy —■ ■ 1

~Letters from counsel for the narties,

consenting to the filing of this brief,

are being filed with the Clerk.

k'k /— 'Statements describing each organization

appear in the Appendix to this brief.

1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioner, Elizabeth Anderson Hishon,

an honors graduate of Columbia University

School of Law, was employed in 1972 as an

associate by King & Spalding, an Atlanta

law firm of more than 50 partners, more

than 50 associates and more than 50 non

attorney support staff personnel. She was

only the second woman lawyer to be employed

by the firm. Among the factors that influ

enced her decision to accept employment at

King & Spalding were representations that

she would be considered for partnership af

ter satisfactory completion of five or six

years of employment. After she did not re

ceive a promotion to partnership, Ms. Hishon

was discharged in 1979 pursuant to the

firms's "up or out" policy. She brought

suit under Title VII, claiming discrimina

tion on the basis of sex.

The District Court for the Northern

2

District of Georgia, after refusing to grant

discovery on the merits, dismissed Ms. Hish-

on's complaint under Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)

(1), holding that, as a matter of law, Title

VII did not govern decisions to promote an

associate in a law firm to partnership. 24

FEP Cases 1303 (N.D.Ga. 1981). On appeal,

the Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Cir

cuit affirmed, over the vigorous dissent

of Circuit Judge Tjoflat. 658 F,2d 1022

(11th Cir. 1982).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The ruling of the courts below, exempt

ing decisions involving promotion to law

firm partnerships from scrutiny under Title

VII, should be reversed by this Court. In

the face of more than a century of overt

discrimination against women in law, the

decision, if sustained, would reverse the

very real and substantial progress women

have made towards achieving equality of em

ployment opportunity in the legal profession.

3

The decision should be reversed because

it is based on an inaccurate and idealized

view of partnerships as purely voluntary

organizations distinct from other corporate

forms of business organization. In fact,

partnerships in the legal profession, as

well as many other professions, are commonly

large, complex business organizations, and

are functionally very similar to the corpo

rate form of professional business organiza

tion .

Contrary to the ruling below, the fail

ure to promote petitioner to partner, re

sulting in her termination due to King and

Spalding's "up-or-out" policy, was an employ

ment decision cognizable under Title VII.

Lucido v. Cravath Swaine & Moore, 425 F.

Supp. 123, 127 (S.D.N.Y. 1977) and is there

fore a "term, condition, or privilege" 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a)(1981) of employment as

an associate. Title VII's broad mandate to

eliminate employment discrimination clearly

_ 4 -

extends to promotional opportunities.

Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) .

Moreover, the Eleventh Circuit erred in

its analysis of the interests at stake in

this case. This Court has expressly held

that discriminatory acts are not justifiable

in the name of free association, Norwood v,

Harrison, 413 U.S. 455, 470 (1973), and that

governmental policies intended to further

compelling governmental interests, such as

those embodied in Title VII, may justify re

strictions on associational interests.

CSC v. Nat'1 Assoc, of Letter Carriers,

413 U.S. 548 (1973) .

Finally, the widespread use of the

partnership form of business organization by

numerous professions and industries through

out our economy would extend the effect of

the lower court's ruling far beyond simply

law firms.

5

I. THE DECISION BELOW WOULD UNDERMINE THE

SUBSTANTIAL PROGRESS WOMEN HAVE MADE

TOWARDS ACHIEVING EQUALITY OF EMPLOY

MENT OPPORTUNITY IN THE LEGAL PROFESSION,

It has been over one hundred years

since Mr. Justice Bradley upheld the right

of Illinois to deny Myra Bradwell admis

sion to the practice of law, characteriz

ing her exclusion as an "adaptation" neces

sary to preserve and protect women's proper

role in society:

It is true that many women are

unmarried and not affected by

any of the duties, complications,

and incapacities arising out of

the married state, but these

are exceptions to the general

rule. The paramount destiny and

mission of woman are to fulfill

the noble and benign offices of

wife and mother. This is the

law of the Creator. And the

rules of civil society must be

adapted to the general consti

tution of things, and cannot be

based upon exceptional cases.

Bradwell v. Illinois, 83 U.S. (16 Wall)

130, 141-42 (1873).

-6-

The case of Myra Bradwell is, today,

an unfortunate and embarrassing relic of

judicial history. No state would presently

deny a woman the right to nractice law

solely because of her sex. But while women

have indeed made substantial progress to

wards achieving equality in the legal pro

fession, the entrenched biases of more than

a century of overt discrimination against

them continue to impede their full inte

gration and participation at the highest

and most prestigious levels of the profes

sion, specifically, elevation to partner

ship in large law firms.

It is, of course, the legality under

Title VII of discriminatory practices en

gaged in by law firms to limit women's op

portunities for promotion to partner which

is at issue in this case. As the last

major barrier to true equality in their

employment, its importance cannot be over

stated. The ruling below, which would deny

-7-

women, as well as male members of minority

groups, the right to invoke the protections

of Title VII at this critically important

stage of their careers, is a devastating

step backwards, and should be overturned

by this Court.

The importance of this ruling is under

scored by acknowledging that it is only

since the passage of Title VII nearly twenty

years ago that women have emerged as a sig

nificant demographic group both within the

law schools and within the profession.

Between 1910 and 1970, women represented

less than 4% of this nation's lawyers; in

1982, women comprised approximately 157. of

all lawyers. Bureau of Labor Statistics,

U.S. Dept, of Labor, Employment and Earn

ings - -Household Data Annual Averages,

Table 23, p. 158 (January 1983). The sta

tistics on law school enrollments are even

more striking: in 1963, women accounted for

only 3.87o of all law students; by 1980, the

-8-

percentage of women enrolled in this nation’s

law schools had risen to 33.5%. C. Epstein.

Women in Law 53 (1981).

The reason for the dramatic growth in

the participation of women in the law during

the last twenty years, following so many

years of stagnation, is directly traceable

to the elimination of a host of discrimi

natory practices engaged in by law schools

and employers throughout much of the previ

ous period. For example, while most of

the "elite" law schools had abandoned their

exclusionary admission practices by the

turn of the century (Michigan, 1870; Yale,

1886; Cornell, 1887; New York University,

1891; Stanford, 1895). Epstein, supra,

at 50, exclusionary policies continued

in some instances until as recently

as 1972.— ̂ And even when these exclusion-

— ^Washington and Lee finally began admit

ting women in 1972. Notre Dame opened its

doors to women in 1969, Harvard in 1950,

and Columbia in 1928. Epstein, supra,

at 50.

9-

ary practices were formally eradicated,

women encountered in their place informal

quotas limiting their enrollment, and more

rigorous admission criteria likewise making

it more difficult for them to gain accen-

2 /tance,— Epstein, supra p. 9 , at 51.

Of course, eliminating the barriers to

their admission to law school did not im

mediately remove other obstacles to their

advancement in the legal profession. For

example, many of the initial women graduates

found themselves steered towards only par-

~2~7— ~ — ----------------— 'While admissions officers routinely de

nied that qualified women were barred by

any such quota system, alleging instead

that it was women's apparent lack of in

terest in the law which accounted for their

small enrollment, many law school faculty

members have since acknowledged that

quotas on women had in fact existed until

the 1960's.. Epstein, supra p. 9 , at 52.

The likely existence of quotas and stricter

admissions criteria is also indicated in a

study published by the Harvard Law Record

in 1965. The study notelI~EHat" aTthougFT'the

proportion of women students had remained

at 3-47o since 1950, the number of applica

tions had "skyrocketed." In 1951, 19 of

the 36 women applicants were admitted; in

1965, only 22 of the 139 women applicants

were accepted. Id. at 53.

-10-

ticular kinds of legal work. A 1958 U.S.

government publication advised women law

yers to concentrate on "real estate and

domestic relations work, women's and juve

nile legal problems, probate work and patent

law," undoubtedly a reflection of women's most

realistic job opportunities. Epstein, supra

p. 9 , at 81. That law firms were expressly

not interested in hiring women prior to the

passage of Title VII was further evidenced

in a survey undertaken by the Harvard Law

Record in 1963, for the purpose of ascer

taining what law firms looked for in candi

dates for employment. The Record asked 430

private law firms across the country which

traits they valued most highly in evaluat

ing new recruits, as well as those they

deemed undesirable. While firms predict

ably placed a high value on scholarship and

initiative, Epstein, supra p. 9 , at 83,

the traits deemed undesirable, other than

a poor academic record, included sex (women),

-11-

race (Blacks), and religion (Jews). Id.

Women were apparently considered undesir

able by firms of all sizes in all parts of

the country and in fact, while Jews, Blacks,

and women were all consistently rated nega

tively, women drew the most negative rating

1 /of the three. Id,— '

With the emergence of legal services

and public interest law firms, jobs with

these agencies also proved predictably more

available to graduating women lawyers than

big corporations or large law firms, pri

marily because of their lower salaries and

—'̂In a 1970 survey of women and men graduates

from Harvard Law School, it was found that while

women were likely to be awarded more employ

ment interviews than their male colleagues,

men received more job offers--a finding

which the researcher concluded indicated

that women's employment choices were more

circumscribed than men's, Glancy, Women

in Law: The Dependable Ones, 21 Harv. L.S,

BuTTTTJo . 5, '2T7”^~(June 1970). In fact,

the researcher found that a much higher

percentage of men (727o) than women (527>)

went to work for law firms immediately fol

lowing graduation, which was again viewed

as a reluctance on the part of law firms to

hire women attorneys. Id. at 26.

-12-

less attractive working conditions.Hochberger,

Women in Law--How Far Rave They Come?, New

York Law Journal, March 21, 1977, p. 1. A

survey conducted by the National Association

of Law Placement in 1975 found that, whereas

only 5.5% of that year's graduating class

went to public interest or legal services

jobs, 12% of the women graduates took these

positions. Id.

Women did not really begin to gain ac

cess to the large law firms until the 1970's.

At the beginning of the last decade, there

were no more than forty women attorneys em

ployed in New York's largest law firms; by

1980, their numbers had swelled to more than

six hundred. Epstein, supra p. 9 , at 175.

A look at the hiring patterns in large lav/

firms throughout the country during this

same period reveals a similar growth in the

percentage of women associates, to over 21%

-13-

by 1980 , — Id.

The striking gains of the 1970's were

due in large part to the initiation of law

suits against some of New York's largest

and most prestigious law firms for blatantly

discriminatory recruitment and hiring prac-

5 /tices,— Two of these cases advanced to

the trial stage, Kohn v. Royall, Koegel &

Wells (now Rogers & Wells), 59 F.R.D. 515

(S.D.N.Y. 1973), appeal dism,,496 F„2d 1094

— ' k survey conducted by the National Law

Journal in 1982 of the 151 largest law

firms showed that women comprised about 17%

of the lawyers in these firms. Flaherty,

Women and Minorities: The Gains, Kat'l

Law Journal!") Dec. 20, T982") at T.

5 /— The lawsuits were initiated by a group of

New York University and Columbia women lav;

students who were outraged by the conduct

and statements of many of the large firms'

interviewers. Comments ranged from asser

tions that women were not good litigators,

and that their participation in litigation

would have to be limited to brief-writing,

to admissions of actual bias in the firms

which relegated women to "blue sky" work

(keeping abreast of changes in state securi

ties laws), involving virtually no client

contact and which is today delegated to para

legals in most large law firms. Epstein,

suprji P - 9 , at 185.

-14-

(2nd Cir, 1974) and Blank v. Sullivan &

Cromwell, 418 F. Supp. 1 (S.D.N.Y. 1975).

In both cases, the defendant law firms

eventually agreed to offer a specific per

centage of its positions each year to female

graduates, Epstein, supra p. 9 , at 185,

as did some of the other law firms cited in

the initial complaints (and who were guar

anteed anonymity). Id.

Unfortunately, the emergence of women

in the last ten to twenty years as a sig

nificant proportion of law graduates and

associates in large lav? firms has done lit

tle to change their continuing scant repre

sentation at the partnership level of these

firms. In 1956, there existed only one

woman partner among the large New York law

firms, Epstein, supra p. 9 , at 179. In

1968, there were three. By the summer of

1980, the number of women partners had in

creased to 41; at the same time, of the

3987 partners in the 50 largest law firms in

the country, only 85 were women. Id. In a

-15-

survey conducted by the National Law Journal

in 1982 of the 151 largest law firms in the

country, women, Blacks, and Hispanics com

prised only 4.17o of the partners at those

firms. Flaherty, supra p.13, at 9.

Thirty-two of the firms surveyed had no

women partners at all; 106 had no Black

partners and 133 had no Hispanic partners.

The almost total exclusion of women

from the highest ranks of the legal pro

fession is particularly troubling at a

time when women comprise more than one-

third of all law graduates. Flaherty,

supra p.13, at 11. In the face of so much

progress by the legal profession in eradi-

^^The 1970 Survey of Harvard Law School

male and female graduates, correctly fore

cast this dismal growth in the number of

women partners. Noting that men and women

seemed to start out on an equal salary level,

but that women quickly fell behind, the re

search concluded that "most of [the women

would] never reach the high income, high

status positions many of their male counter

parts achieve." Glancy, supra p .12, at 27.

-16-

eating the effects of more than a century

of discrimination, the decision of the

Eleventh Circuit can only further inhibit

the ability of women to assume their right

ful place beside their male colleagues.

The availability of Title VII to many of

these women in the 1970's was an invaluable

tool for establishing their right to par

ticipate on a more equal footing with their

fellow graduates. As more and more of these

women become eligible for promotion to part

nership, this Court must not deny them the

right to again invoke the protections of

Title VII to ensure that such promotional

opportunities are not unjustly denied them. —

-^Congress clearly was concerned that

Title VII's coverage extend to highly pres

tigious jobs. Senator Javits, in onnosing

a 1972 amendment that would have excluded

hospital-employed physicians from Title VII

coverage said:

One of the things that those discrimi

nated against have resented the most is

that they... cannot ascend the higher

rungs in professional and other life.

Yet this amendment would... reinstate

-17-

ffootnote continued]

the possibility of discrimination on

grounds of ethnic origin, color, sex,

religion--[among] physicians or sur

geons, one of the highest rungs of the

ladder that any member of a minority

could attain--and thus lock in and

fortify the idea that being a doctor

or surgeon is just too good for mem

bers of a minority... that they have

to be subject to discrimination... and

the Federal law will not protect them.

118 Cong. Rec. 3802 (1972).

-18-

II. THE LOWER COURT'S VIEW THAT THE PART

NERSHIP FORM MANDATES EXEMPTION OF

SOME PARTNERSHIP DECISIONS FROM TITLE

VII IS ERRONEOUS.

The Eleventh Circuit's dismissal of

the complaint was based on an idealized

and inaccurate view of the nature of "part

nership" as both essentially a voluntary

association among partners and as clearly

distinct from all corporate forms of busi

ness organizations. Hishon v. King &

Spalding, 678 F.2d 1022, 1026-28 (11th Cir

1982). Contrary to the lower court's as

sumptions, partnerships are business organ

izations that vary dramatically in their

internal structures and the relationships

among partners; they also are functionally

very similar to the corporate form of pro

fessional business organization. The in

accuracy of the Eleventh Circuit's assump

tions fatally undermines its justification

for exempting decisions about promotion to

partnership from Title VII.

19

A. The Eleventh Circuit's Decision

is Based on an Idealized and

Inaccurate View of "Partnerships”

The court of appeals concluded that

the fundamental character of partnerships

required that decisions about promotion to

partnership be exempted from scrutiny un-

Q /

der Title VII,— 7 because "the form is the

substance" distinguishing such decisions

from all other kinds of employment deci

sions, even employment decisions made by

partnerships. 678 F.2d at 1028. In reach

ing this conclusion, the lower court fail-

-g~7------------------

-— 'The explicit exemptions from statutory

coverage do not include elevation to part

nership. See, e.g., 42 U.S.C. §§2000(e)

(b)(bona fide private clubs); 2000e~l,

2000-2(e)(certain religiously based employ

ment) . To the extent that many partner

ships are small, they may fall within the

generalized exemption from Title VII of

businesses with fewer than 15 employees.

42 U.S.C. §2000e(b). The qualities of in

timacy and voluntariness in partnerships

that loomed so large for the lower courts,

see 678 F.2d at 1026, 24 FEP Cases 1303,

1304-05 (N.D.Ga. 1980), have been recog

nized by Congress through this size limi

tation on Title VII coverage.

- 20

ed to recognize the substance behind the

form.

In fact, partnerships vary substan

tially in size, details of organization,

and relationships among the partners. Far

from being oases of intimacy and collegial-

ity, many partnerships are large business

es that exhibit marked differences among

partners in power, income, influence, and

formal position.

This is hardly surprising, especially

in view of the large size of many partner

ships. A 1980 survey found more than 100

law firms with 100 or more lawyers, and

45 with more than 150. National Law Jour

nal, Oct. 6, 1980, at 34-39. King &

Spalding placed number 106 on this list.

Id. Eighty-two of the firms had at least

as many partners as King & Spalding's 51,

and twenty had at least 75. Id.

The size of the "Big Eight" account-

21

ing firms— is even more striking. In

1981, these eight firms had approximately

7,000 partners in the United States. N.Y.

Times, Jan. 3, 1982, at Dl, col.l . To

gether these firms employ 150,000 people

in 2,500 offices in more than 100 nations.

Annually, they interview 160,000 students

from United States colleges and universi

ties, hire 10,000 new professional employ

ees and make more than 1,000 new partners.

Stevens, supra, at 8. Furthermore, large

size is not restricted to these eight firms.

Seidman & Seidman, the nation's tenth larg

est CPA firm, has 160 partners and $50

million in annual revenues. Id. at 160.

Within the management structure of

9 /

_

— They are: Arthur Andersen; Arthur

Young; Coopers & Lybrand; Deloitte Haskins

& Sells; Ernst & Whinney; Peat, Marwick,

Mitchell; Price Waterhouse; and Touche

Ross. They are "huge multinational busi

ness organizations, the largest profession

al firms in the world, and some of the

most influential powers on earth.” M.

Stevens, The Big Eight 2 (1981).

22

such large businesses, there is bound to

be a significant degree of differentiation

among partners. Some law firms have a

chairman or presiding partner, in charge

of making day-to-day decisions for the

firm. P. Hoffman, Lions in the Street 14, 52

(1973); J. Stewart, The Partners 112 (1983).

The degree of power exercised by only one

partner in a group of 50 or more can be

formidable.

At [one firm], for example, the

presiding partner makes the final

determination of each partner's

share of income, worked out through

individual conferences with part

ners. He determines the agenda

of the partnership's Tuesday lunch

es. He resolves conflicts among

the partners, smoothes ruffled

feathers and disciplines when

necessary.

Stewart, supra, at 242.

More common is the executive commit

tee, usually made up of a small number of

the most senior partners. This institu

tion has been described as follows:

23

The executive committee acts

as overseer for the firm. It is

the deciding group; it settles pol

icy matters and disputes. The

main, specific task of the commit

tee is to decide on percentages

distributed to partners. Members

of the group discuss questions about

setting up pension plans or moving

their offices. Those at the summit

make the initial determination

about whether new partners are

needed. They decide, if the prob

lem becomes overt, about the opti

mum size of the firm. The execu

tive committee concerns itself

with problems of office morale;

of client satisfaction. The

committee acts as referee and

serves to ease conflict within

the firm.

E. Smigel, The Wall Street Lawyer 237 (1963)

(footnotes omitted). See also Nelson,

Practice and Privilege: Social Change and

the Structure of Large Law Firms, 1981 Amer.

Bar Fdn. Research J. 97, 120.

More rarely, but quite significantly,

partnerships have formally stratified sys

tems. One now-dissolved New York law firm,

for example, is described as having two

classes of partners: "proprietary" and

"non-proprietary." Proprietary partners

24

match the Eleventh Circuit's idea of "part

ners," who have an interest in the profits

of the firm and make crucial decisions,

such as who else will become a proprietary

partner. Non-proprietary partners, however,

strongly resemble what even the Eleventh

Circuit would agree are "employees." They

are essentially salaried, and able to share

in profits only at the discretion of the

proprietary partners. National Law Journal,

Apr. 25, 1983, at 9, col. 1.— ^

A very strong centralization of con

trol over business decisions is also evid

ent in large accounting partnerships. They

have executive committees, chairmen (or

managing partners), and vice-chairmen.

Although rare, such formal stratifica

tion is not extinct. For example, a small

number of employers recruiting at Harvard

Law School in 1982 indicated the existence

of a formal "junior partner" status in

their firms. Harvard Law School Placement

Office, Employer Directory Fall 1982 (avail

able in Harvard Law School Library).

25

These partners "establish current and long

term policies, set procedures, [and] approve

partner earnings..." Stevens, supra p.22,

at 32-33. The autonomy of the less power

ful partners is severely limited, as noted

by Stevens:

Each partner's interest in a Big

Eight firm is only a tiny fraction

of a percent. What’s more, they

can be reprimanded, shifted from

client to client, and relocated

across the fifty states, often

against their will. This is hardly

the kind of treatment 'business

owners' have to tolerate.

Id. at 32.

Large differences among partners is

further reflected in their widely varying

incomes. Even the "edited version," 678

F.2d at 1025, of King & Spalding's 1974

partnership agreement, supplied during dis

covery in the instant case, strongly sug

gests that not all active King & Spalding

partners receive equal shares of the part

nership income. See Joint Appendix (here

inafter, "Jt.App.") at 155. A decade ago,

26

a survey of law firms of twenty-five or more

lawyers reported a large disparity in earn

ings among partners. Almost half the firms

that responded indicated that their highest

paid partners earned at least four times

the income of their newest, and least well-

paid, partners. Orren, A Look Inside Those

Big Firms, 59 A.B.A.J. 778, 779 (1973).

A similar pattern exists in accounting

firms. For example, new partners at Touche

Ross earn $50,000 a year, whereas the firm's

chairman earns at least $500,000 a year.

Even at Price Waterhouse, which has the

smallest intra-partnership earning dispari

ties among the "Big Eight," partners' sala

ries range from $75,000 to $200,000.

Stevens, supra p. 22, at 31.

As the above discussion demonstrates,

many partnerships are large, complex, high

ly structured and highly stratified busi

ness organizations. Instead of looking at

the realities of the many varieties of part

27

nership structure and practice, especially

of the large professional partnerships, the

court of appeals relied on an idealized

vision of "a partnership." In so doing, it

erroneously constricted the reach of Title

VII.

B. The Eleventh Circuit Erroneously

Construed Title VII by Focusing

on Formal Differences and Ignor

ing Functional Similarities Be

tween Corporate and Partnership

Forms of Organization in Profes

sional Services Businesses

The inadequacy of the lower court's

conception of the partnership form as lim

iting Title VII's coverage is further dem

onstrated by comparing partnerships to the

analogous corporate form, the professional

corporation. These two forms of business

organization do not differ in any respects

that are significant for purposes of Title

VII analysis. However, in a professional

corporation, the principals are employees

of the corporation. Applying the Eleventh

Circuit's "clear distinction between the

28

employees of a corporation and the partners

of a law firm," 678 F.2d at 1028, would then

yield the odd result that all employment

decisions made by law firm professional

corporations would be subject to scrutiny

under Title VII, but some decisions by law

firm partnerships would not be. The func

tional similarity between partnerships and

professional corporations, however, shows

both the shallowness of the lower court’s

analysis and the dangers to Title VII if

this Court adopts that analysis.

The principal difference between part

nerships and professional corporations has

been in aspects of federal income tax treat

ment of the two forms. Certain disparities

in the tax treatment of corporations, on

the one hand, and self-employed profession

als on the other, triggered the development

of professional corporations side by side

with partnerships. See Blum, Professional

Incorporation: Social Change Created by

29

the Tax Laws, 14 Tax Notes 51 (Jan. 11

1982); Wood, The Desirability of Profession

al Corporations after the Economic Recovery

Tax Act, 60 Taxes 261 (1982). For high in

come taxpayers the difference in treatment

of pension contributions was significant.

In 1981, the maximum deductible annual con

tribution to her Keogh (or H.R.10) plan was

the lesser of 15 per cent of her net earn

ings from self-employment, or $15,000. S.

Rep.No. 494, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 314

(1982). By contrast, the maximum, deductible

contribution for a corporate plan covering

a lawyer was $45,475 for 1982. Id. at 313.

In both cases, these funds, in a qualified

pension trust, would earn investment in

come tax-free, and would be taxed to the

beneficiary only when received after re

tirement. However, this differential has

been largely eliminated by the Tax Equity

and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982, Pub.

L. 97-248 ("TEFRA"). See Conference Com

30

mittee Report, H.Rep.No. 760, 97th Cong.,

2d Sess. 621 (1982)("The Conference agree

ment generally eliminates distinctions in

the tax law between qualified pension, etc.

plans of corporations and those of self-

employed individuals....").

Aside from these tax differentials in

benefits programs, there are virtually no

significant substantive differences between

partnerships and professional corporations.

For example, a professional corporation

must adhere to corporate formalities. See

Rev. Rul. 70-101, 1970-1 C.B. 278-280,

amplified Rev. Rul. 70-455, 1970-2 C.B. 257;

Rev. Rul. 72-468, 1972-2 C.B. 647, modified

Rev. Rul. 73-556, 1973-2 C.B. 424, amplified

Rev. Rul. 74-439, 1974-2 C.B. 405, Rev. Rul.

82-212, 1982 U.S. Tax Week 1973. Profes

sional corporations are also subject to pay

roll-based taxes, such as the federal un

employment tax, on all their professional

employees, while partnerships are not so

31 -

taxed on their partners. See Tax Management

Portfolio - TEFRA at A-270 and note 55

(1983) .

In the two areas where one might expect

the traditional distinction between corpo

rate and partnership forms to be signifi

cant for Title VII purposes, it does not

exist. Because of considerations of pro

fessional ethics and licensing, partnerships

and professional corporations alike do not

have the traditional corporate attributes

of limitation of individual liability and

ability freely to transfer shares and/or

raise outside capital.

Professional corporation statutes do

not generally allow a professsional to es

cape liability for her own torts (e.g.,

malpractice), nor those committed by those

under her supervision. See, e .g ., Ga.

Code §14-7-7 (1982); N.Y. Bus. Corp. Law

§1505(a)(McKinney's Supp. 1982). Indeed,

in Georgia the professional corporation

32

form has been held not to insulate the pro

fessional employees of the corporation from

liability for the torts committed by other

professional employees. First Bank & Trust

Co. v. Zagoria, 51 U.S.L.W. 2529 (Ga. Feb.

23, 1983).

Moreover, professional corporation

statutes generally require that all stock

in professional corporations be owned by

persons licensed for, and actively engaged

in, the practice of the relevant profession.

See, e.g., Ga. Code §14-7-5(a)(1982); N.Y.

Bus. Corp. Law §§1507, 1511 (McKinney Supp.

1982). In essence, such statutory require

ments have eliminated the traditional cor

porate separation between "ownership,"

through ownership of stock that is freely

transferable, and "employment" in the cor

poration. In practice, stock in profession

al corporations is held by professional em

ployees of the corporation. This ownership

interest, however, does not make the prin

33

cipals any the less employees of the corpo

ration .

These limitations on the traditional

attributes of corporations in the profes

sional corporation context serve to high

light the inadequacy of the lower court's

view that the uniqueness of partnerships re

quires that they be given special exemption

from Title VII.— ̂ The functional simil-

127--------------------— Moreover, by focusing on the partnership

form as the basis for its decision, the

court of appeals presented the possibility

that businesses wishing to avoid Title VII

liability for some employment decisions

could become partnerships in order to ig

nore Title VII. Although there are usually

strong economic disincentives involved in

choosing a form of business organization

for such reasons, even in part, there is

currently an opportunity for professional

corporations to convert to partnerships

without some of the usual economic conse

quences. Ordinarily "disincorporation'1 of

a successful professional corporation would

be likely to precipitate a significant tax

liability to the shareholder-employees, see

26 U.S.C.A. §331(a)(West Supp. 1983); 26

U.S.C.A. §1001 (West 1982). Recognizing

that TEFRA's elimination of pension-related

tax benefits might cause some professional

corporations to liquidate, Congress enact

ed TEFRA §247 (not codified) as "disincor

poration relief." Conference Committee

34

arities between the corporate and partner

ship forms of organization demonstrate that

the Eleventh Circuit's distinction between

corporations and partnerships is indeed

form without substance.

[footnote con't]

Report, H.Rep.No. 760, 97th Cong. 2d Sess.

634 (1982). In 1983-1984, professional

corporations will be able to liquidate with

out many of the negative tax consequences

that usually attend such a change. Thus,

there is little or no economic barrier to

changing the partnership form of business

organization in order to avoid Title VII.

In addition, it is possible that some part

nerships in non-professional fields that

might have economic reasons for wanting to

incorporate, would forego incorporation in

order to retain their partial immunity to

Title VII. The decision of the court of

appeals, which permits these perverse re

sults, would seriously undermine Title

VII's goals.

35

III. DECISIONS ON PROMOTION TO PARTNER

SHIP ARE EMPLOYMENT DECISIONS SUB

JECT TO SCRUTINY UNDER TITLE VII

A. The Termination of Employment as

the Result of an "Up or Out"

Policy is an Employment Decision

Under Title VII

As Judge Tjoflat correctly observed,

Ms. Hishon was fired from King & Spalding.

678 F.2d at 1030. Although King & Spalding

contended below that Ms. Hishon's losing

her job was merely an effect of the deci

sion not to offer her partnership, that

distinction is both artificial and false.

In the "up or out" policy adhered to by

King & Spalding, 678 F.2d at 1024, failure

to become a partner and failure to maintain

one's employment as an associate are two

sides of the same coin. "Up or out" promo

tion policies are almost universal among

large law firms. Hoffman, supra

p. 23, at 6-7; Smigel, supra p . 21, at 44,

114-16; Nelson, supra p. 24, at 122/

"Permanent associates are a dying breed."

-36-

Hoffman, supra, at 144; see also Stewart,

11/supra p . 23, at 156.— Associates either

become partners or must leave the law firm;

in short, get promoted or get fired. See

Jt. App. at 31-32 (Answer 1[9).

Discriminatory discharge is explicitly

proscribed by Title VII. 42 U.S.C. §20Q0e-

(a)(1). There is no question that, at the

time of her discharge, Ms. Hishon was an em

ployee of King & Spalding. Jt. App. at 48-

49 (affidavit of James Sibley). In the

analogous situation presented in Lucido v .

Cravath, Swaine & Moore, 425 F.Supp. 123,

127 (S.D.N.Y. 1977), the district court

held that the plaintiff had been an employee

of the defendant law firm throughout the

period of the alleged discrimination, in

cluding his failure to be made a partner

— 'Interestingly, King & Spalding had_one

permanent associate at the time Ms. Hishon

was hired. The permanent associate was al

so the only woman associate in the firm's

87-year history to that point. Jt. App. at

187.

-37-

and consequent discharge from the firm.

The Eleventh Circuit in the instant case

failed to apply the correct analysis devel

oped by the court in Lucido, and erroneous

ly affirmed the dismissal of Ms. Hishon's

claim.

Moreover, in the specialized area of

academic employment, where tenure decisions

are strikingly similar to the "up or out"

partnership decisions at issue in this case,

courts have applied Title VII in scrutiniz

ing decisions not to award tenure to faculty

members. See Lieberman v. Gant, 630 F.2d

60, 64 (2d Cir. 1980); Kunda v. Muhlenberg

College, 621 F.2d 532, 535 (3d Cir. 1980).

Like the decision to promote an associate

to partner, tenure decisions are made after

periodic evaluation of the employee's suit

ability for tenure and they confer what is

essentially a guarantee of continued employ

ment. See Lieberman v. Gant, 630 F.2d at

64. Also, as with partnership,

-38-

a tenured employee is moved into the ranks

of those people who make the important man

agerial decisions about the enterprise--

including, significantly, decisions about

who else should be awarded tenure. See

NLRB v. Yeshiva University, 444 U.S. 672

(1980). Most importantly, the failure to

be awarded tenure is also followed by loss

of academic employment in that institution.

Tenure decisions, as well as partner

ship decisions, are the result of complex

and varying processes. The complexity of

the tenure decision-making process, however,

has not led courts to hold them to be out

side the scope of Title VII. Similarly,

there is no reason to conclude in the in

stant case that because King & Spalding's

process of discharging Ms. Hishon was com

plex and protracted, it produced something

other than a discharge. Ms. Hishon's alle

gation that the discharge was in violation

of Title VII is a claim over which the fed

-39-

eral courts have jurisdiction, and the Elev

enth Circuit erroneously dismissed it.

B. Progression from Associate to

Partner is Clearly an Expecta

tion of Employment as an Associate

Large law firms, such as King & Spald

ing, generally recruit law school graduates

as associates, give the associates a certain

number of years to prove themselves, and

then either promote them to partnership or

fire them. See Jt. App. at 30-32 (Answer

1fs 8-9); Hoffman, supra p. 23, 6-7;

Smigel, supra p. 24, at 114-16; Nelson,

supra p. 24, at 122. Thus, partnership is

a critical component of an associate's

career path in the firm.

Law firms recruit law school graduates

for jobs as associates with clear reference

to the ultimate goal of partnership. It

is commonly understood by students that

successful performance as an associate is

rewarded with partnership. It is also

understood by law firms that employment of

-40-

associates is the first step in acquiring

new partners. Many law firms take the po

sition that "they hire only people of part

nership caliber." Nelson, supra p. 24 , at

126. More significant than the general

statement is the fact that many firms spe

cifically use this argument in recruiting

new associates. For example, a sampling

of information supplied by firms recruiting

at Harvard Law School in 1982 reveals that

a significant number tell students that

they only hire potentially partnership

worthy people as associates . — ̂ About a

quarter of the firms in Atlanta, half the

Houston firms, a third of the Boston firms,

a third of the Chicago firms, and a fifth

“ 'The sample of law firms considered here

includes only those submitting an individ

ual statement, in addition to the standard

ized form required by the Harvard Law School

Placement Office. Thus, the percentages

can not be generalized to apply to all firms

in each city. Nevertheless, they are sig

nificant evidence of prevalence of the

clearly marked career path from new associ

ate to partner. (Information available in

Harvard Law School Library).

-41-

of the Los Angeles firms presented them

selves as hiring people they consider capa

ble of becoming partners. The connection

between associateship and partnership that

is evident in the recruiting practices of

large law firms contradicts King & Spald

ing's contention that promotion to partner

ship is wholly different from other employ

ment decisions made by law firms.

Once an associate begins working in a

large law firm, the work, incentives, and

system of performance evaluation are geared

toward partnership as the goal. The possi

bility of becoming a partner is "the strong

est reward" in the incentive system of al

most all large law firms. Smigel, supra

p. 24 , at 259. The years of hard work and

long hours that most associates put in are

part of their jobs as associates, but are

also the key building blocks in advancement

to partnership. Associates work hard because

they know that it will help them to be

-42-

come partners. See, e .g ., Stewart, supra

p. 23 , at 86.— /

Similarly, the evaluation of associ

ates' work, in most large firms, stresses

the associate's partnership potential.

Such partnership-oriented evaluations may

begin as early as two years after an associ

ate has been hired. National Law Journal,

Apr. 4, 1983 at 40, col. 1. The longer an

associate has been with the firm, the more

clearly connected to partnership the evalu

ations become. See Jt. App. at 46-47 (affi

davit of James Sibley). King & Spalding,

like many other large firms, has institu

tionalized this process, making partnership

decisions a fixed number of years after an

associate is hired. 678 F.2d at 1024. The

partnership decision itself is merely the

most definitive in the series of evaluations

1 5 /— A similar incentive pattern is found in

large accounting firms. See Stevens, supra

p. 22 , at 28-29.

-43-

of associates, each focused on the associ

ate as potential partner.

It is, therefore, clear that the oppor

tunity to progress from associate to partner

is a "term, condition, or privilege," 42

U.S.C. §2000e~2(a), of employment as an

associate. Title VII's broad mandate to

eliminate employment discrimination clearly

extends to promotional opportunities, at

both lower-level and executive and manager

ial levels. Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975).— / In the instant

case, promotion to the ranks of the firm's

— See, e .g ., Payne v Travenol Labs, 673

F. 2d 798 (5th Cir". 1982) , ~ cert. denied , 74

L.Ed.2d 605 (1983)(promotions to technical,

managerial and executive level jobs); U.S.

Postal Service Bd. of Governors v. Aikens,

51 U.S.L.W. 4354 (U.S. Apr. 4, 1983)(mana-

gerial positions); Sweeney v. Bd. of Trus

tees of Keene State College! 569 F.2d 169

(1st Cir.), vacated and remanded on other

grounds, 439 U.S. 24 (1978), 604 F.2d 106

(1st Cir. 1979)(academic promotions);

Gilmore v. Kansas City Terminal Railway Co.,

509 F.2d 48, 5T (8th Cir. 1975)"(managerial

and supervisory positions); Pinckney v .

County of Northampton, 512 F. Sunn.989

TE.D.Pa. '1981) , a ^ d , 681 F.2d 808 (3rd

Cir. 1982)(administrative positions).

-44-

management carries with it other changes in

the associate's position, such as security

of tenure. These additional factors, how

ever, which are present in many other mana

gerial or executive-type promotions, do not

alter the nature of the claim of employment

discrimination. The associate has, under

any circumstances, been part of an employ

ment system that leads either to partner

ship or to unemployment, and is therefore

entitled to the protection of Title VII.

See Lucido v. Cravath, Swaine & Moore, 425

F. Supp. at 128.

C. Partnership Decisions are not

Protected by the Freedom of

Association

The Eleventh Circuit's conclusion that

the anti-discrimination policies of Title

VII are outweighed by the King & Spalding's

partners' freedom of association misper-

ceives the nature of that freedom and re

sults in a perversion of clear Congression-

-45-

al intent to outlaw discrimination.

This Court has never recognized a right

of association independent of other consti

tutional guarantees. One commentator de

scribed freedom of association as "little

more than a shorthand phrase used by the

Court to protect traditional first amend

ment rights of speech and petition as exer

cised by individuals in groups.” Raggi,

An Independent Right to Freedom of Associ

ation , 12 Harv. C,R.-C.L. L. Rev. 1 (1977).

See also, Tribe, American Constitutional

Law, 701-703 (1978); Young & Herbert, Polit

ical Association under the Burger Court:

Fading Protection, 15 U. Cal. Davis L. Rev.

53, 54 n. 4 (1981). Although individual

justices have tried to articulate a general

notion of freedom of association independ

ently deserving constitutional protection,

see, e .g ., Justice Marshall's dissent in

Village of Belle Terre v. Boraas, 416 U.S.

1, 15-18 (1974) and Justice Douglas' con

-46-

currence in United States Department of

Agriculture v. Moreno, 413 U.S. 528, 540-

45 (1973) , this Court as a whole has tended

to recognize freedom of association as be

ing tied to some underlying First Amendment

right. See, e ,g ., Citizens Against Rent

Control/Coalition for Fair Housing v. City

of Berkeley, 454 U.S. 290 (1981)(city ordi

nance placing limits on expenditures and

contributions in campaigns on ballot meas

ures violated citizens' groups' rights of

political speech and association)- Widmar

v. Vincent, 454 U.S. 263 (1981)(if univer

sity makes facilities generally available

to registered student groups, it may not

discriminate on basis of content of speech

against groups wishing to use facilities

for religious worship and discussion).

Further, this Court has expressly and

consistently held that discriminatory acts

are not justifiable in the name of free

association. As this Court held in Norwood

-47-

v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455, 470 (1973):

Invidious private discrimination

may be characterized as a form of

exercising freedom of association

protected by the First Amendment,

but it has never been accorded

affirmative constitutional pro

tections .

And, even when recognizing a freedom

of association for the purpose of express

ing or advocating beliefs, this Court clear

ly has denied any unrestricted right to act

on those beliefs. This principle, recog

nized as early as NAACP v. Alabama ex rel.

Patterson , 357 U.S. 449, 460 (1958), was

recently reaffirmed in Runyon v. McCrary,

427 U.S. 160, 176 (1976). In Runyon,

this Court held that requiring a private

school, committed to the promotion of racial

segregation, to admit black children did

not infringe any freedom of association en

joyed by the school, the parents, or the

children. As Justice Stewart wrote, the

school's discriminatory practice could not

be rationalized as a form of freedom of

-48-

association because a legally mandated open

admissions policy would not affect the con

tent of what was taught:

[I]t may be assumed that parents

have a First Amendment right to

send their children to educational

institutions that promote the belief

that racial segregation is desirable,

and that children have an equal

right to attend such institutions.

But it does not follow that the

practice of excluding racial

minorities from such institutions

is also protected by the same

principle. As the Court stated in

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455,

"The Constitution ... places no

value on discrimination,' id., at

469, and while 1[i]nvidious private

discrimination may be character

ized as a form of exercising free

dom of association protected by

the First Amendment ... it has

never been accorded affirmative

constitutional protections ...'

427 U.S. at 176.— /

Runyon involved the same issue of law

presented in the instant case--whether

17 /— Cf. Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v.

United States, 379 U.S. 241, 258TTT7T964)

(upholding constitutionality of the public

accommodations provisions of Title II of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964):

[footnote con't on following page]

-49-

it is a violation of the First Amendment

freedom of association to apply an anti-

discrimination statute to a commercial or

ganization. This Court rejected the associ

ational claim in Runyon for precisely the

reason that it should be rejected here: no

right or ability to advocate any point of

view is infringed when a discriminatory

promotional policy is invalidated. 427 U.S

at 176-77.

This Court has held that governmental

policies intended to further a compelling

[footnote con't from preceding page]

The only questions are: (1)

whether Congress had a rational

basis for finding that racial dis

crimination by motels affected

commerce, and (2) if it had such

a basis, whether the means it

selected to eliminate that evil

are reasonable and appropriate.

If they are, appellant has no

'right' to select its guests as

it sees fit, free from govern

mental regulation.

See also Railway Mail Ass'n y. Corsi, 326

U.S. 88, 93-94 (1945)(due process does not

prohibit state from banning racial discrim

ination in union membership),

-50-

state interest, like the anti-discrimina

tion principles embodied in Title VII, may

justify restrictions on associational in

terests. CSC v. Nat'l Assoc, of Letter

Carriers, 413 U.S. 548 (1973)(restrictions

on the associational rights of federal em

ployees justified by interest in effective

government); Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1,

24-28 (1976)(limitations on the associa

tional rights of campaign contributors jus

tified by interest in avoiding actuality

and appearance of political corruption).

Acting in disregard of these principles,

the Eleventh Circuit resolved the conflict

between Title VII and rights of association

by simply eliminating Title VII from its

analysis.

Favoring the associational interst of

King & Spalding over Congressional intent

to bar discrimination in employment contorts

the nature of the associational right and

makes a mockery of Title VII. Without

-51-

question King & Spalding, in considering

whether to make Elizabeth Hishon a partner,

was making a business decision. See Jt.

App. at 45-48 (affidavit of James Sibley).

Assertions of constitutionally guaranteed

associational rights of the law firm nei

ther obfuscate the nature of the partner

ship decision nor transform it into a deci

sion warranting constitutional protection.

This Court's opinions suggest that the con

stitutional protection accorded political

speech and association is not as great when

applied to ordinary business activities.

Compare In re Primus, 436 U.S. 412 (1978)

(reversing a reprimand of an attorney who,

on behalf of the American Civil Liberties

Union, had solicited a client; distinguish

ing "traditional fee paying arrangements,"

and noting representation involved could

not be viewed as "motivated by considera

tions of pecuniary gain rather than ...

[the] goal of vindicating civil liberties,"

-52-

436 U.S. at 429-30); with Ohralik v. Ohio

State Bar Ass'n, 436 U.S. 447 (1978)(af

firming disciplinary actions against an

attorney who improperly solicited clients,

noting that a "lawyer's procurement of re

munerative employment is a subject only

marginally affected with First Amendment

c o n c e r n s 436 U.S. at 459).

Title VII prohibits sex discrimination

in employment--it does not interfere with

the exercise of discretion in the non-dis-

criminatory selection of new partners. To

hold otherwise is to adopt a view of the

right of association which transcends all

other considerations of law and the Consti

tution and which is wholly unsupported by

this Court's previous rulings on the para

meters of associational rights.

-53-

IV. TITLE VII'S APPLICATION TO PARTNER

SHIPS AFFECTS MANY IMPORTANT SECTORS

OF THE ECONOMY, HOT SIMPLY LAW FIRMS

An exception to Title VII for promo

tions in a partnership like King & Spald

ing would have an impact on industries and

professions beyond law firms. In large

part because of its malleability, partner

ship is a common form of business organi

zation in this country. As this Court has

noted, "some of the most powerful private

institutions in the nation are conducted

in the partnership form." Beilis v. United

States, 417 U.S. 85, 93 (1970). In 1980,

1,379,654 businesses including roughly 8.4

million partners filed partnership tax re

turns with the Internal Revenue Service,

Internal Revenue Service, Dept, of the

Treasury, Statistics of Income-1980 Part

nership Returns Table 1, p. 10 (1982) (here

inafter cited as Statistics of Income-1980) .

Use of the partnership configuration for a

-54-

business is growing. In 1979, 1,299,593

businesses filed partnership returns, Inter

nal Revenue Service, Dept, of the Treasury,

Statistics of Income-1979 Partnership Re

turns Table 1, p. 10 (1982) and in 1978,

1,234,157 did so. Internal Revenue Service,

Dept, of the Treasury, Statistics of Income-

1978 Partnership Returns Table 1, p. 8

(1982). These partnerships account for a

significant amount of business. In 1980,

for example, partnerships had total re

ceipts of almost $300 billion, Statistics

of Income-1980 Table 1, p. 10.

Partnerships can be found throughout

all segments of the nation's economy. For

example, in 1980, there were 8,228 partner

ships of certified public accountants con

sisting of 53,274 partners, which earned

$6.65 billion in receipts. Statistics of

-55-

Income-1980 Table 1, p. 18. In addi

tion, partnerships are widely used in the

engineering and architectural fields (6,675

partnerships) id.; farming (108,094 part

nerships), id. at 10; construction (66,590

partnerships), id. at 11; wholesale and

retail trades (200,273 partnerships), id.

at 13; insurance (7,127 partnerships), id.

at 15; personal services, including laun

dries, beauty and barber shops (25,607 part

nerships), id. at 17.

Because use of the partnership form of

business organization permeates this na

tion's many professions and industries, a

holding by this Court excluding partner

ships from scrutiny under Title VII will

— / See supra Section II for discussion of

the importance of the "Big Eight" certi

fied public accounting firms. In addition,

there were 4,783 partnerships of other ac

counting, bookkeeping and auditing services

which included 12,564 partners and

$505,000,000 total receipts. Statistics of

Income-1980 Table 1, p. 18.

-56-

effectively exempt a large number of busi

ness organizations from the proscriptions

of that Act. This is particularly disturb

ing at a time when the number of women part

ners in many of the above-mentioned fields

continues to lag so significantly behind

the increasing numbers of women entering

these fields. —

Public accounting firms, for example,

are large employers of female certified

public accountants. According to a recent

— / Between 1980 and 1981, the number of

women accountants doubled, resulting in an

increase in the number of women accountants

from 25.2% to 38.5% of the field. Bureau

of Labor Statistics, U.S. Dept, of Labor,

The Female-Male Earning Gap: A Review of

Employment and Earnings Issues Table 5, p.

8 (Sept. 1982). Over the same period, the

number of women engineers nearly tripled,

resulting in a jump from 1.67, of all engin

eers being women to 4.3%. Id. In the five

years from 1975 to 1980, the number of fe

male architects doubled, so that women now

comprise 6.7% of the field as compared with

4.3% in 1975. Greer, Women in Architecture

A Progress (?) Report and a Statistical

Profile, AIA Journal, Jan. 1982, aF 40

(hereinafter cited as Women in Architec

ture) .

-57-

survey conducted by the American Woman's

Society of Certified Public Accountants,

587o of its membership and that of the Amer

ican Society of Women Accountants were em

ployed in public accounting firms in 1981,

almost 30% of which were national firms.

American Woman's Society of Certified Pub

lic Accountants, A 1981 Statistical Profile

of the Woman Certified Public Accountant

(1981). Of these women, only 17.9% were

partners in their firms, while 34.5% were

considered non-supervisory. Id, The num

ber of women partners in the "Big Eight"

firms is even more dismal. As the New York

Times reported in 1977, the "Big Eight" firms

averaged fewer than three female partners

each. More Women Moving into Public Ac

counting, But Few to the Top, N.Y. Times,

Dec. 17, 1977, at 18. According to Forbes,

in 1981 only one of the 125 new partners at

Peat, Marwick, Mitchell was a woman, a pat

tern replicated throughout the "Big Eight."

-58-

Women accounted for three of Arthur Ander

sen's 168 new partners; three of Arthur

Young's 57 new partners; none of Price-

Waterhouse's 36 new partners; three of De-

loitte Haskins and Sells’ 64 new partners;

one of Coopers & Lybrand's 70 new partners,

two of Touche Ross' 58 new partners, and

one of Ernst & Whinney's 75 new partners.

Ms. CPA, Forbes, Aug. 17, 1981, at 8 . — 1

20/— The attitudes that women in the "Big

Eight" must fight against can be both vi

cious and entrenched, as illustrated by

Stevens, supra p. 22 , at 22.

'They really were the good old days

back when I was an active partner,'

says a retired Big Eight auditor....

'It was a gentleman's business, that's

what I liked about it. Now, it's

like the UN there.... You don't

have anything in common with your

partners... I just can't get used

to it. I mean, in my day lunchtime

was a relaxed affair. A good meal

and good conversation with men of

your own ilk. Now if you want to

tell a joke, you have to look around

the table first. One of your part

ners may be Negro, Spanish, a Jew,

or a woman. You know how sensitive

they are.'

-59-

In view of these facts, it is not surpris

ing that the limited chance for promotions

was one of the most frequent reasons given

by the women accountants in the surveys

described above for leaving their previous

position. American Woman's Society of Cer

tified Public Accountants, supra p. 58.

Similar patterns exist for women en

gineers and architects. For example, ac

cording to a 1982 survey of its membership

conducted by the Society of Women Engineers,

62.4/o of its members were employed in pri

vate industry, but roughly half had no

regular supervisory responsibility. Only

87c served as managers or general managers.

Society of Women Engineers, A Profile of

the Woman Engineer 3, Table 2 p. 4, Table 7

p. 6 (1982). A survey conducted in 1981 by

the American Institute of Architects Jour

nal found that the majority of women archi-

-60-

tects were employed in architectural firms.

Women in Architecture at 40. The survey

results strikingly indicate a significant

rise in the number of women who report be

ing subject to discrimination in their work

experience -- 56% in 1981 as compared with

40% in a similar survey conducted in 1974.

Id. Of these victims of discrimination,

577c indicated they had suffered discrimina

tion in advancement, 54% in work assign

ments and 51% in hiring. Many of the sur

vey participants responded that it was dif

ficult, if not impossible to move to mana

gerial positions in some architectural

21/firms.— In the words of one woman, "It

is extremely difficult to continue to grow

21/— Many also commented that discrimination

has detrimentally affected their sense of

self esteem and self confidence, as one

respondent said, "by having to re-prove

myself in each new situation, rather than

being accepted without questions as a com

petent professional. Women in Architecture,

at 40.

-61-

within a firm in terms of management, scope

of responsibility and salary, Most men be

come threatened when a woman gains compet

ence in their areas." Id.— ^

An exception to Title VII for promo

tions to partnership thus promises to

shield more than just law firms from prohi

bitions against discrimination and reach

~TTl— Clearly, the sluggishness with which

these fields have responded to the in

creased numbers of women has an impact be

yond those women currently eligible to be

considered as partners. Women at all le