Harrison v. NAACP Statement of Jurisdiction

Public Court Documents

June 23, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harrison v. NAACP Statement of Jurisdiction, 1958. 2f904c83-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/08da68e8-71a4-45b4-85d5-9b396d3f6c17/harrison-v-naacp-statement-of-jurisdiction. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

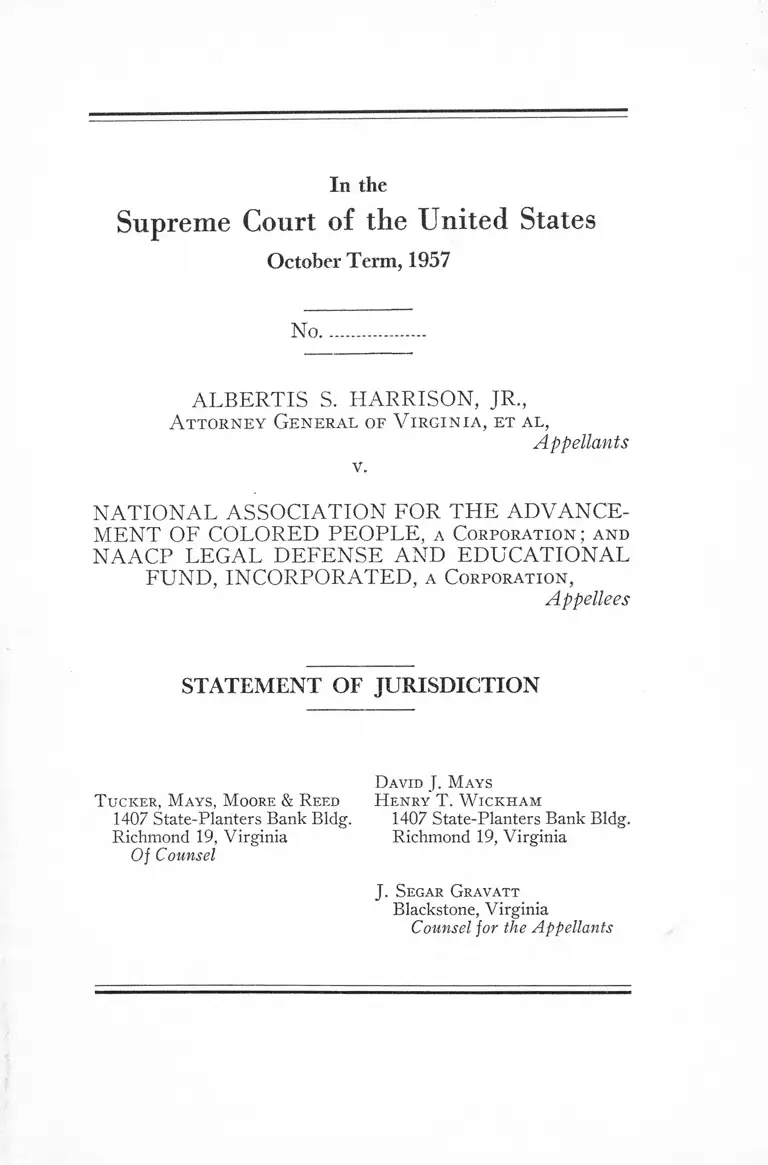

In the

Suprem e Court of the U nited States

October Term, 1957

No.

ALBERTIS S. HARRISON, JR.,

A tto r n ey G e n e r a l of V ir g in ia , et a l ,

Appellants

v.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCE

MENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, a C o r po r a t io n ; and

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INCORPORATED, a C o rpo ratio n ,

Appellees

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

T u c k er , M ays , M oore & R eed

1407 State-Planters Bank Bldg

Richmond 19, Virginia

Of Counsel

J . S egar G ravatt

Blackstone, Virginia

Counsel for the Appellants

D avid J . M ays

H en r y T . W ic k h a m

1407 State-Planters Bank Bldg.

Richmond 19, Virginia

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

O p in io n of Court B e l o w ............... ........................ - .................................. 1

T h e J u r isd ic tio n of t h e C o u r t ...................... ...................................—. 1

T h e Q u estio n s P r e s e n t e d ..... ................................................................... 3

S ta te m e n t of t h e C ase ................... ...................................... ........... — 3

T h e Q u estio n s P r esen ted A re S u b s t a n t ia l .................................. 12

A p pe n d ix :

I. Opinion of the Three-Judge District Court.............App. 1

II. The Statutes Involved....................... App. 95

III. Judgment of the Court Below................................. ...App. 106

IV. The Alabama Statute .................................. App. 107

V. The North Carolina Statute ............ App. 109

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp. 563 ............................................. 14, 16

Burroughs v. United States, 290 U. S. 534 ................ ......... .......... 19

Communist Party v. Subversive Activities Control Board, 223

F. 2d 531................ ....... ......... ............................... ......... ............ 18

Douglas v. Jeanette, 319 U. S. 157................................................... 13

Electric Bond & S. Co. v. S. E. C., 303 U. S. 419 ............. ............. 19

Government & C. E. O. C., C. I. O. v. Windsor, 353 U. S. 364

14, 15, 16, 18

Lassiter v. Taylor, 153 F. Supp. 295 ........................-..................... 16

Lewis Publishing Company v. Morgan, 229 U. S. 288 ................. 19

McCloskey v. Tobin, 252 U. S. 107...........................-..... -............. 21

National Ass’n. for Advancement of Colored People v. Patty,

159 U. S. 503 ....................... -.................... -....................... ----- 1, 20

National Union of Marine Cooks v. Arnold, 348 U. S. 3 7 ........... 21

Palmetto Fire Insurance Co. v. Conn, 272 U. S. 295 ......—............ 2

People of State of New York ex rel. Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278

U. S. 63 ............................................-....... ................................... 20

Re Isserman, 345 U. S. 286 ..........................-................................. 21

St. John v. Wisconsin Employment Relations Board, 340 U. S. 411 2

Page

Sonzinsky v. United States, 300 U. S. 506 ...................... -........ — 19

Spielman Motor Sales Co. v. Dodge, 295 U. S. 8 9 ............... ......... 13

Stefanelli v. Minard, 342 U. S. 117...........................-...................... 13

Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U. S. 197...... ....................... ................ 13

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 ....... ............................... -.......... 20

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U. S. 7 5 ........................... 12

United States v. Harriss, 347 U. S. 612..................................... 17, 18

Viereck v. United States, 318 U. S. 236 ..................-..................... 18

Watson v. Buck, 313 U. S. 387 ................................. -...................... 12

Other Authorities

Acts of the General Assembly of Virginia,

Extra Session, 1956:

Chapter 31 ................................................. 2, 3, 9, 11, 16, 17, 20

Chapter 32 ............ ................. — ........... 2, 3, 10, 11, 16, 17, 20

Chapter 35 .......................... .............................. 3, 11, 16, 20, 21

Page

Code of Virginia, 1956 Additional Supplement:

Section 18-349.9........................................................... 3

Section 18-349.17........................................................................... 3

Section 18-349.25............................................................. ............ . 3

United States Code:

Title 2:

Section 241 ............................................................................... 19

Section 261 .............................. 18

Title 26:

Section 1132............................................................................. 19

Title 28:

Section 1253 .... 2

Section 1331 ............................................................................. 2

Section 1332 ................ 2

Section 1343(3) ..................................................- ................ 2

Section 2281 ............................................................................. 2

Section 2284............................................................................. 2

Title 50:

Section 786 ................................................................................ 18

In the

Supreme Court of the U nited States

October Term, 1957

No.

ALBERTIS S. HARRISON, JR.,

A tto rney Ge n er a l of V ir g in ia , et a l ,

Appellants

v.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCE

MENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, a Co r po r a t io n ; and

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INCORPORATED, a C o rpo ratio n ,

Appellees

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

I .

OPINION OF THE COURT BELOW

The opinion of the three-judge United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Divi

sion, is reported at 159 F. Supp. 503 (1958) as National

Ass’n. for Advancement of Colored People v. Patty and

is found, together with the dissenting opinion, as Appendix

I to this statement.

II.

THE JURISDICTION OF THE COURT

1. The cases below were brought by the appellees to

secure a declaratory judgment and an injunction restraining

2

the appellants from enforcing five state statutes. A three-

judge court was convened pursuant to 28 U. S. C. Sections

2281 and 2284 and jurisdiction was invoked under 28 U.

S. C. Sections 1331, 1332 and 1343(3). This appeal is

taken from the judgment of the three-judge court declar

ing three state statutes to be unconstitutional and enjoining

their enforcement against the appellees. The statute pur

suant to which this appeal is brought is 28 U. S. C. Sec

tion 1253.

2. The date and time of entry of the judgment sought

to be reviewed by this appeal is April 30, 1958. The notice

of appeal was filed in the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division, on

May 22, 1958.

3. Section 1253 of Title 28, U. S. C. confers on this

Court jurisdiction of this appeal and reads as follows:

“Except as otherwise provided by law, any party

may appeal to the Supreme Court from an order grant

ing or denying, after notice and hearing, an interlocu

tory or permanent injunction in any civil action, suit

or proceeding required by any Act of Congress to be

heard and determined by a district court of three

judges.” (June 25, 1948, c. 646, 62 Stat. 926.)

4. The following cases sustain the jurisdiction of this

Court:

(a) St. John v. Wisconsin Employment Relations Board,

340 U. S. 411, 414 (1951); and

(b) Palmetto Fire Insurance Co. v. Conn, 272 U. S. 295,

305 (1920).

5. The validity of three state statutes is involved. Chap

ters 31 and 32, pp. 29-33, Acts of the General Assembly of

3

Virginia, Extra Session, 1956 (respectively codified as Sec

tions 18-349.9 et seq. and 18-349.17 et seq. of the Code of

Virginia, 1956 Additional Supplement, pp. 32-36) are reg

istration statutes. Chapter 35, pp. 36-37, Acts of the Gen

eral Assembly of Virginia, Extra Session, 1956 (codified

as Section 18-349.25 et seq. of the Code of Virginia, 1956

Additional Supplement, pp. 36-37) relates to the crime of

barratry. Due to the length of these statutes they are not

here set out verbatim. Their text is set forth as Appendix

II to this statement.

III.

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Did the three-judge district court err in refusing to

dismiss the complaints pertaining to Chapters 31, 32 and

35, Acts of the General Assembly of Virginia, Extra Ses

sion, 1956, on the grounds, or any one of them, set forth

in the defendants’ motions to dismiss?

2. Did the three-judge district court err in enjoining the

enforcement of Chapters 31, 32 and 35, Acts of the General

Assembly of Virginia, Extra Session, 1956, against the

plaintiffs on the ground that the said statutes deny them

rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States?

IV.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

As previously mentioned, these cases were heard before

a statutory three-judge court on the complaints of the appel

lees seeking declaratory judgments and permanent injunc

tions against enforcement and operation of certain statutes

enacted by the General Assembly of Virginia.

4

The facts material to the consideration of the questions

presented are as follows:

The National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People, hereinafter referred to as the NAACP, is a

membership corporation organized under the laws of the

State of New York. The principal object of the NAACP

is to advance the interests of colored people. It is financially

supported by contributions from local branches which are

issued charters. These branches are grouped into an asso

ciation called the Virginia State Conference of NAACP

Branches, and for all practical purposes, the branches and

the State Conference are constituent parts of the NAACP.

Oliver W. Hill and Spottswood W. Robinson, III, Rich

mond attorneys, are members of the Legal Committee of

the NAACP as well as being members of the Legal Com

mittee of the Virginia State Conference. Hill is also

chairman of the last-mentioned committee and Virginia

Counsel for the NAACP and its Virginia Registered Agent.

In addition, Robinson is the Southeast Regional Counsel

for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, a

New York membership corporation, hereinafter referred

to as the Legal Defense Fund.

The Activities of the Legal Defense Fund

One of the main purposes of the Legal Defense Fund is

to render legal aid gratuitously to such Negroes as may

appear to be worthy and who are suffering legal injustice by

reason of race and are unable to employ counsel on account

of poverty. Thurgood Marshall is Director and Counsel

of the Legal Defense Fund and has under his direction a

legal research staff of six full-time lawyers who reside in

New York City. In addition, the Legal Defense Fund has

lawyers in several sections of the country on a retainer basis

5

and approximately 100 volunteer lawyers throughout the

country who come in to assist whenever needed. The Legal

Defense Fund also has at its disposal social scientists, teach

ers of government, anthropologists and sociologists.

The income of the Legal Defense Fund is derived mainly

from contributions solicited by letter and telegram from

New York City. It is approved by the State of New' York

to operate as a legal aid society because of the provisions of

the barratry statute in effect in New York State.

Costs, expenses and investigations of legal cases on behalf

of Negroes are borne by the Legal Defense Fund and it

will pay attorneys’ fees and bear the costs of a suit by a

private litigant to recover damages for violation of civil

rights, especially if the principle involved in the particular

lawsuit has not been established.

While it was conceded the Legal Defense Fund should

represent only those people who cannot afford to pay for

litigation, it was stated that no investigations are made to

determine the financial conditions of the parties who may

request and receive assistance, and the record in this case

clearly indicates that many Negroes who are receiving the

assistance of the Legal Defense Fund are not in poverty.

The Activities of the NAACP

Speaking of the legal activity of the NAACP, Roy Wil

kins, Executive Secretary thereof, testified:

“Well, under legal activity we have sought to assist in

securing the constitutional rights of citizens which

may have been impaired or infringed upon or denied.

We have offered assistance in the securing of such

rights. Where there has been apparently a denial of

those rights, we have offered assistance to go to court

and establish under the Constitution or under the fed

6

eral laws or according to the federal processes, to seek

the restoration of those rights to an aggrieved party.”

(Tr.,pp. 70-71)

Wilkins further testified that in assisting plaintiffs “we

would either offer them a lawyer to handle their case or to

help to handle their case and pay that lawyer ourselves, or

we would advise them, if they had their own lawyer, would

advise them or assist in the costs of the case” (Tr., p. 82).

No money ever passes directly to the plaintiff or litigant.

The NAACP does not ask a person if he wishes to

challenge a law. However, it does say publicly that it be

lieves that a certain law is invalid and should be challenged

in the courts. Negroes are urged to challenge such laws

and if one steps forward, the NAACP agrees to assist.

Although it is not in the regular course of business, pre

pared papers have been submitted at NAACP meetings

authorizing someone to act in bringing lawsuits and the

people in attendance have been urged to sign.

Robert L. Carter, General Counsel for the NAACP, is

paid to handle legal affairs for the corporation. Representa

tion of the various Virginia plaintiffs falls within his duties.

The NAACP offers “legal advice and assistance and coun

sel, and Mr. Carter is one of the commodities” (Tr., p. 125).

Thurgood Marshall was Special Counsel for the NAACP

prior to 1957 and it was his job “to advise with lawyers and

the people in regard to their legal rights and to render what

ever legal assistance could be rendered” (Tr., p. 308).

The State Conference has a legal staff composed of thir

teen members and in every instance except two, Negro

plaintiffs in civil right cases have been represented by mem

bers of such staff in cases in which assistance is given. All

prospective plaintiffs are referred to the Chairman of the

Legal Staff, Oliver W. Hill, and counsel for such plaintiffs

7

makes his appearance when Hill has recommended that they

have “a legitimate situation that the NAACP should be

interested in” (Tr., p. 39).

The State Conference assists in cases involving discrim

ination and the Executive Board formulates certain policies

to be applied in determining whether assistance will be given.

Hill then applies these policies and when he decides that the

case is a proper one, it is taken “automatically” with the

concurrence of the President (Tr., p. 47).

Members of the Legal Staff of the State Conference may

attend meetings held by the branches in their capacity as

counsel for the Conference and either the particular branch

or the State Conference pay the traveling expenses incurred.

Oliver W. Hill testified that he is not compensated as

chairman of the Legal Staff. It is his duty to advise Negroes

who come to him voluntarily “or directly from some local

branch, or after having been directed there by Mr. Banks”

whether or not he will recommend to the State Conference

that their case will be accepted (Tr., p. 131).

After a case is accepted, Hill selects the lawyer. He refers

the case to a member of the Legal Staff residing in the par

ticular area from which the complaining party came. For

the Richmond area, “one of us would frequently handle the

situation” (Tr., p. 133).*

A bill for the legal services is submitted to Hill who

approves it with the concurrence of the President of the

State Conference. Hill further stated that no investigation

is made as to the ability of the plaintiffs to pay the cost of

litigation. He feels that irrespective of wealth, a person has

* It should be pointed out that Hill as well as Spottswood W. Robin

son, III, also a member of the Legal Staff of the State Conference, both

being residents of Richmond, not only represented all the plaintiffs as

counsel of record in the Prince Edward, Arlington, Charlottesville,

Newport News and Norfolk school segregation cases, but took active

and leading parts in the trial of said cases.

8

the right “to get cooperative action in these cases” (Tr.,

p. 156).

Economic Reprisals

The appellees, in an attempt to substantiate allegations

set forth in their complaints concerning harassment, abuse

and economic reprisals against their members and contribu

tors, examined eight witnesses in the court below. It is a

fair summary to state that several of these witnesses told

only of social reprisals, while the eighth testified that she was

a cleaning woman doing day work and that one of her em

ployers dismissed her after her name appeared in the news

paper as being one of the plaintiffs in the Charlottesville

school segregation case. However, there was no evidence

that she was a member or contributor to the NAACP or

the Legal Defense Fund. Furthermore, it was stipulated

by counsel that she had been fully employed by white em

ployers since the discharge aforementioned.

The Necessity for Chapters 31 and 35

While a number of Negro plaintiffs in the Prince Edward

County school segregation case admitted signing a paper

which actually authorized the bringing of that lawsuit, they

also testified:

1. They did not know that they were plaintiffs in the

case until the year 1957, though it was initially brought

in 1951.

2. When they signed the so-called authorization papers

they thought only that they would obtain a better or new

school for their children.

3. They have never had any communications from the

attorneys allegedly representing them concerning the said

lawsuit.

9

Another witness who is a plaintiff in the Charlottesville

school segregation case stated that he had had no conver

sation or written correspondence with the attorneys who

brought that suit, all of his contacts being with the NAACP.

Still another, who is also a plaintiff in the Charlottesville

case testified that he signed an authorization paper at a meet

ing of the NAACP at which time no lawyers were present.

Another witness on behalf of the appellants testified that

the solicitation of personal injury claims is widespread in

Virginia, as well as in the rest of the country; that the divi

sion of fees is also widespread as well as offering of financial

enducements to solicit business; and that running and cap

ping is indulged in by unethical attorneys and laymen in

their employ. This witness was an Eastern Representative

of the Claims Research Bureau of the Law Department of

the American Railroads and stated that the information

required by Chapter 31 would help alleviate the conditions

described by him.

The Necessity for Chapter 32

Dr. Francis V. Simkins, professor of American History

at Longwood College, Farrnville, Virginia, testified that he

has made a special study of Southern history. As to the

history of secret societies, he stated that the Union League,

formed in 1862 to promote patriotism in the North, spread

to the South where it became an organization of Negroes

and carpetbaggers. Its membership list was secret and

under that cloak of secrecy its members committed acts of

violence.

The Ku Klux Klan was the most important secret society

in the South. It was notorious for the crimes it committed.

The Klan has had the tendency to reappear periodically and

it exists today because of racial tensions. Statutes requiring

10

the disclosure of membership lists help curb the harmful

activities of such organizations.

John Patterson, the Attorney General of Alabama, re

counted instances of racial disturbances and violence occur

ring in the State of Alabama, including the so-called “Mont

gomery bus boycott situation,” instances in Birmingham,

the Town of Maplesville, Marion and Tuskegee. General

Patterson then pointed out that such a registration law as

Chapter 32 “would help the authorities to enforce the law,

catch the offenders, and possibly help us identify organiza

tions that are working in certain areas so that we could take

preventive measures to prevent the things from happening

before they do” (Tr., pp. 570-571).

The Superintendent of the Virginia State Police and

four county sheriffs testified that Chapter 32 would be of

help in law enforcement. The sheriffs generally stated that

an order to integrate the public schools would cause more

racial tension, possibly bloodshed, and would raise difficult

law enforcement problems. Secret organizations would

antagonize the situation and in their opinion, the provi

sions of Chapter 32 would aid in crime detection, the pre

vention of violence and would be helpful in selecting addi

tional deputies who may be needed in time of racial

disturbances.

Sheriff C. F. Coates, on cross-examination, further testi

fied that a colored man had just complained to him that the

NAACP placed pressure on him to join the local Branch.

The testimony is as follows:

“A colored man in my community came to me, on

yesterday, and told me that the NAACP had put pres

sure on him to try to make him join the NAACP. He

refused to join. They instructed him that he had to

join and he had to vote like they said to vote, and if

11

there was any bloodshed in that community from inte

gration of the school that the NAACP was going to

be in the middle of it. He refused to join it. The head

of this organization, so he said, on account of him

refusing to join their organization, had sent a bunch

of thugs around to his place to tear it up.” (Tr., pp.

458-459)

The Motives of the Legislature

Harrison Mann, a member of the House of Delegates

from Arlington County, testified that he was the chief

patron of Chapters 31, 32 and 35 and was responsible for

the drafting of Chapters 32 and 35 prior to the special

session of the General Assembly held in 1956.

Mann’s reasons that prompted him to strive for the enact

ment of the statutes in question were:

1. The Autherine Lucy incident in Alabama and the

violence ensuing therefrom.

2. John Kasper was beginning his operations in Wash

ington, right across the Potomac River.

3. Existing racial tension in Virginia.

4. The Prince Edward plaintiffs ignorance of the fact

that they had brought a lawsuit.

5. The actions of the NAACP in Texas in soliciting and

paying litigants.

6. Charges of certain Arlington lawyers that the NA

ACP was engaged in practicing law.

7. Certain white organizations were commencing suits

in Maryland, Kentucky, Louisiana and elsewhere.

8. The organization of the Defenders in Virginia and

the recurrence of the Ku Klux Klan in Florida.

12

V.

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED ARE

SUBSTANTIAL

The three-judge court below, by judgment entered April

30, 1958, a copy of which is found as Appendix III to this

statement, decided questions of such substantial nature as

to require plenary consideration by this Court, with briefs

on the merits and oral argument, for their resolution for

the following reasons:

A.

The Complaints Filed in the Court Below Do Not State

Cases or Controversies Within the Meaning of Either

Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution of the United

States, or Section 2201 of Title 28, U. S. Code.

It must be emphasized that the appellees requested the

court below to enjoin the enforcement of criminal statutes

of the Commonwealth of Virginia, though there has been

no threat of prosecution. A general threat by officials to

enforce laws which they are charged to administer is not a

sufficient case or controversy over which this Court should

exercise its equity jurisdiction. United Public Workers v.

Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75 , 88 (1947) and Watson v. Buck

313 U. S. 387, 400, 401 (1941).

B.

Under the Circumstances Presented by These Cases the

Court Below Should Not Have Restrained the Enforce

ment of Criminal Statutes of the Commonwealth of

Virginia.

In the absence of danger of great, immediate and irrep

13

arable injury, a federal court, in the exercise of its equity

jurisdiction, will not interfere with a state in the execution

of her criminal statutes. Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. S.

157, 163-64 (1943) and Spielman Motor Sales Co. v. Dodge,

295 U. S. 89, 95 (1935).

In other words, even assuming for sake of argument that

there had been a threat of prosecution, the circumstances

of these cases did not justify the interference of a court of

equity. At worst, the only palpable and legal injury present

was the possibility of a fine—a consequence hardly demand

ing interference of any court of equity. Spielman Motor

Sales Co. v. Dodge, supra, at p. 96. Compare, Terrace v.

Thompson, 263 U. S. 197 (1923), where the plaintiff would

have had to risk confiscation of his real property in order to

test the validity of a state statute in a criminal prosecution.

To conclude, it is appropriate to quote the following

language from Stefanelli v. Minard, 342 U. S. 117, 120

which dealt with the discretion of federal courts in enjoining

state criminal proceedings:

“* * * Here the considerations governing that dis

cretion touch perhaps the most sensitive source of

friction between States and Nations, namely, the active

intrusion of the federal courts in the administration of

the criminal law for the prosecution of crimes solely

within the power of the States.”

C .

The Court Below Should Not Have Enjoined the Enforce

ment of State Statutes Which Have Not Been Authori

tatively Construed by the State Courts.

The doctrine of equitable abstention is involved here and

it is only necessary to examine the majority and minority

14

opinions of the court below to conclude that a substantial

question is raised by this appeal.

Without analysis, the majority cited five decisions of this

Court and relied strongly upon a dissenting opinion of the

late Chief Tudge Parker in Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp.

563 (D. C. E. D. S. C., 1957) in holding:

“The policy laid down by the Supreme Court does

not require a stay of proceedings in the federal courts

in cases of this sort if the state statutes at issue are

free of doubt or ambiguity. * * *” (159 F. Supp. 503,

533)

Notwithstanding its conclusion, the majority opinion

seemed to recognize that recent decisions of this Court raised

doubts as to the proper application of the doctrine of equita

ble abstention. It was stated at p. 523:

“Neither are we given any clear formula to follow

under the decisions of the Supreme Court. The more

recent decisions of the highest court suggest that stat

utory three-judge courts should be hesitant in exer

cising jurisdiction in the absence of state court action,

or at least a reasonable opportunity to secure same.

* * 3fs”

Nothing can be added to the exhaustive dissenting opinion

of the court below. The decisions relied upon by the majority

were analysed and found not to be controlling. Further, the

dissenting opinion points to and examines many decisions of

this Court, including the recent case of Government & C.

E. O. C., CIO v. Windsor, 353 U. S. 364 (1957), and finds:

“The majority adopts that portion of the dissenting

opinion in Bryan v. Austin, and proclaims as a policy

of judicial interpretation that a stay of proceedings in

15

the Federal Courts is not required in cases in which

the state statutes at issue are free of doubt or ambiguity.

It is respectfully submitted that the pronouncement of

such a doctrine is not warranted by the authorities cited.

It is true that in some few cases the Supreme Court has

not required such prior interpretation but this fact falls

far short of establishing a rule of procedure under

which proceedings in a Federal Court in a case such as

this should be stayed only where the statute involved is

so ill-defined that its constitutionality is doubtful until

it is construed judicially. (159 F. Supp. 503, 543)

* * *

“* * * The majority have elected to base their deci

sion upon authority for which the most that can be

said is that it is of a negative character and upon a

‘prophecy of foreshadowing “trends”.’ This method

of judicial interpretation based upon prophecy was

commented upon and rejected by the Supreme Court

in Spector.” (atp. 548)

The factual background, as well as the language of this

Court in the Windsor case, supra, clearly indicates that the

question presented merits the full consideration of the Court.

There, the plaintiff sought an injunction restraining the en

forcement of a state statute restricting the rights of certain

public employees of a state to join or participate in labor

organizations. The statutory three-judge court held that

the doctrine of equitable abstention applied since the state

courts had not rendered a definitive construction of the

statute. 116 F. Supp. 354 (N. D. Ala., 1953) affm’d. with

out opinion, 347 U. S. 901 (1954). The plaintiff then

applied to a state court for relief, contending only that the

union was not subject to the terms of the statute. Consti

tutional questions were not raised. The Supreme Court of

Alabama affirmed the decision of the lower court, agreeing

that the union was subject to the terms of the statute, and

the plaintiff returned to the federal forum where it was held:

16

“* * * it is clear to us that the Alabama courts

have not construed the Solomon Bill in such a manner

as to render it unconstitutional, and, of course, we

cannot assume that the State courts will ever so con

strue said statute. * * *” (146 F. Supp. 214, 216

(1956))

This Court vacated the judgment of the district court and

said:

“* * * The bare adjudication by the Alabama Su

preme Court that the union is subject to this Act does

not suffice, since that court was not asked to interpret

the statute in light of the constitutional objections

presented to the District Court. If appellants’ freedom-

of-expression and equal-protection arguments had been

presented to the state court, it might have construed

the statute in a different manner. * * *” (353 U. S.,

supra, at p. 366)

The Alabama statute before the Court in the Windsor

case, supra, is set forth in full as Appendix IV to this state

ment. When this statute is considered and compared with

Chapters 31, 32 and 35 of the Acts of the General Assembly

of Virginia, Extra Session, 1956, it is plain that the majority

below erred in refusing to apply the doctrine of abstention.

The Virginia statutes are not “free of doubt or ambiguity,”

as the majority implies, under the decision of the Windsor

case.*

As suggested in the dissenting opinion, an issue of vital

importance is involved, namely, the proper balance between

* Compare also the North Carolina statute, set forth as Appendix

V to this statement, which was under consideration in Lassiter v.

Taylor, 152 F. Supp. 295 (E. D. N. C., 1957). There, the doctrine

of equitable abstention was applied under the authority of the Windsor

case. It is interesting to note that the late Chief Judge Parker, who

wrote the dissent in Bryan v. Austin, supra, was a member of the three-

judge court.

17

state and federal courts. Under such circumstances, this

Court should review the decision of the court below and

clarify the doctrine of equitable abstention and its applica

tion by the lower federal courts.

D.

The Constitutionality of Chapters 31, 32 and 35, Acts of

the General Assembly of Virginia, Extra Session, 1956

Chapters 31 and 32 require the registration of certain

persons, firms, associations and corporations with the State

Corporation Commission, while Chapter 35 relates to the

improper practice of law by defining the crime of barratry.

Chapter 31 applies to those engaged in the solicitation of

funds for the purpose of financing or maintaining litigation

to which they are not parties or in which they have no pecuni

ary rights or liabilities. Chapter 32 applies not only to those

engaged in the activities described in Chapter 31, but is also

directed to advocates of racial integration or segregation and

is designed to relieve interracial tension and to prevent the

violation of the anti-lynching laws of the state. It also re

quires registration before promoting or opposing the pas

sage of legislation on behalf of any race.

The majority of the court below held that Chapters 31

and 32 violated freedom of speech, and relied strongly on

United States v. Harriss, 347 U. S. 612 (1954). In so doing,

it was made abundantly clear that the doctrine of equitable

abstention should have been applied, even when accepting

as correct the principles stated by the majority on this point.

For example, Clause (1) of Section 2 of Chapter 32, con

cerning the promoting or opposing the passage of legislation,

was construed in such a broad manner as to be considered in

conflict with the Harriss case, supra. It, of course, cannot

be assumed that a state court would construe the clause in

18

question in the same manner if the constitutional issues

raised in the court below were presented in such forum.

Government & C. E. O. C., C. I. O. v. Windsor, supra.

It should also be pointed out that the majority of the

court below held that the terms of Clause (3) of Section 2

of Chapter 32 are too vague and indefinite to satisfy con

stitutional requirements. Again, may it be said that the

state courts would not limit the terms of Clause (3) so as to

satisfy constitutional requirements?

Statutes requiring registration of persons and organiza

tions, who engage in certain activities, or of members of

certain organizations are not new to the jurisprudence of the

United States. Statutes requiring certain persons or or

ganizations to list their sources of income and their expendi

tures with particularity are no rarity. Such statutes are

found in the United States Code as well as upon the statute

books of the States. The statutes have been contested in

court and have been upheld. Further, regulation of persons

who solicit funds from the public, by requiring a reasonable

identification and accounting therefor, has not been consid

ered an imposition upon such solicitors.

The federal lobbying act, 2 U. S. C. Section 261 et seq.,

was upheld by this Court in the Harriss case, supra, and

no doubts as to the constitutionality of the statute requiring

the registration of foreign propagandists or agents of for

eign principals has been expressed. Viereck v. United States,

318 U. S.236 (1943).

50 U. S. C. Section 786 et seq. requires registration and

annual reports of certain Communist organizations. The

registration provisions of this statute were upheld in Com

munist Party v. Subversive Activities Control Board. 223

F. 2d 531 (D. C., 1954), reversed on procedural grounds

in 351 U. S. 115 (1956).

19

The Federal Corrupt Practices Act, 2 U. S. C. Section

241, et seq., provides that the treasurer of a political com

mittee shall file a statement with the name and address of

each person contributing $100.00 in a calendar year and the

name and address of each person to whom an expenditure of

over $100.00 is made. The statute was upheld in Burroughs

v. United States, 290 U. S. 534 (1934).

Another registration act was that contained in the In

ternal Revenue Code of 1939, 26 U. S. C. Section 1132 et

seq., which required registration by “every person possessing

a firearm” with the local district collector. The information

required was the number or other identification of the

firearm, the name and address of the possessor, the place

where the firearm is normally kept, and the place of business

or employment of the possessor. The registration provisions

of this statute were upheld in Sonsinsky v. United States,

300 U. S. 506 (1937).

In the case of Lewis Publishing Company v. Morgan,

229 U. S. 288 (1913), the Federal statute requiring users

of the mails for newspapers or other publications to furnish

each year a sworn statement of the names and post office

addresses of the editor, the publisher, the business manager

and the owners or stockholders, if the publication was a

corporation, and the bondholder, mortgagees and other

security holders was upheld.

In the case of Electric Bond & S. Co. v. S. E. C., 303

U. S. 419 (1938), the Public Utility Holding Company

Act of 1935, prohibiting use of the mails upon the failure

to file a registration statement containing certain required

information, was upheld.

Mention of registration statutes above, which have been

upheld by this Court, clearly indicates that a substantial

question is involved in this appeal.

20

Appellants urge that the principles enunciated in Thomas

v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 (1945), have been ignored by the

court below. Further, the majority has improperly con

strued People of State of New York ex rel. Bryant v.

Zimmerman, 278 U. S. 63 (1928). The majority apparently

distinguishes the Zimmerman case on two grounds. First,

it is implied that the Ku Klux Klan is an evil organization,

while the appellee organizations are exceptionally fine or

ganizations which have never caused, and will not cause in

the future, such tension or strife as to warrant the exercise

of the police power of a state. The second ground upon

which the majority places great reliance is legislative pur

pose. Since it was the purpose of the Legislature, accord

ing to the majority, to destroy the appellees, Chapters 31

and 32 cannot be upheld. On this point, the court below has

violated all rules of statutory construction, since it has been

stated that the registration statutes are free from doubt

and ambiguity. Yet, the motives and intentions of the Gen

eral Assembly of Virginia are used to strike down such

legislation.

As pointed out, Chapter 35 creates the statutory offense

of barratry. It conforms to the common law crime with two

exceptions, namely, the barrator must be shown to have

participated in payment of the expenses of the litigation,

but need not be shown to have stirred up litigation on more

than one occasion. The dissenting opinion states that the

“statutory definition of ‘instigating’ is somewhat ambiguous

and will require a judicial interpretation.” 159 F. Supp. at

p. 549. The appellants agree, and once again it is shown

that the majority of the court below should have applied the

doctrine of equitable abstention. May it be said with finality

that a state court would find that the activities of the appel

lees amounted to “stirring up litigation” within the meaning

21

of Chapter 35 if the federal constitutional questions raised

in the court below were properly presented to it?

The majority of the court below concluded that Chapter

35 violated the rights of the appellees guaranteed by the

equal protection clause as well as the due process clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment. No authority is cited for the

conclusion that an arbitrary classification is established by

virtue of the exemption of legal aid societies serving all

needy persons in all types of litigation and the appellees

failed to show that anyone comparably situated has been

treated differently from them. National Union of Marine

Cooks v. Arnold, 348 U. S. 37 (1954).

Moreover, the majority concluded that Chapter 35 vio

lated the due process clause since it was designed to put the

appellees out of business. The fact that an individual,

association, or corporation may be put out of business by

a particular statute is no reason for its invalidity. Re Isser-

man, 345 U. S. 286 (1953).

In concluding, it is to be noted that the majority of the

court below failed to follow the decision in McCloskey v.

Tobin, 252 U. S. 107 (1920), wherein a Texas statute, de

fining with much detail the offense of barratry, was upheld

by this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

T u c k er , M ays, M oore & R eed

1407 State-Planters Bank Bldg.

Richmond 19, Virginia

Of Counsel

D avid J . M ays

H en ry T . W ic k h a m

1407 State-Planters Bank Bldg,

Richmond 19, Virginia

J. S egar G ravatt

Blackstone, Virginia

Counsel for the Appellants

Dated June 23, 1958

22

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the aforegoing statement

of jurisdiction have been served by depositing the same in

a United States mail box, with first class postage prepaid,

to the following counsel of record:

Robert L. Carter

20 West 40th Street

New York 18, New York

Thurgood Marshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Spottswood W. Robinson, III

623 North Third Street

Richmond, Virginia

Oliver W. Hill

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond, Virginia

on this .... . day of June, 1958.

H e n r y T. W ic k h a m

A P P E N D I X

APPENDIX I

Opinions of the Court Below

Before S oper , Circuit Judge, H u t c h e s o n , Chief Judge,

and H o f f m a n , District Judge.

S o per , Circuit Judge.

These companion suits were brought by the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People and

the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

corporations of the State of New York, against the Attorney

General of the Commonwealth of Virginia and the Com

monwealth Attorneys for the City of Richmond, the City of

Newport News, the City of Norfolk, Arlington County and

Prince Edward County, Virginia, to secure a declaratory

judgment and an injunction restraining and enjoining the

defendants from enforcing or executing Chapters 31, 32, 33,

35 and 361 of the Acts of Assembly of the Commonwealth,

all of which were passed at the Extra Session convened be

tween August 27, 1956, and September 29, 1956, and were

approved by the Governor of the Commonwealth on Septem

ber 29,1956.

The suits are based on the allegation that the statutes are

unconstitutional and void, in that they deny to the plaintiffs

rights accorded to them by the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.

Jurisdiction is invoked under the civil rights statutes,

42 U. S. C. §§ 1981 and 1983 and 28 U. S. C. § 1343, under

which the district courts have jurisdiction of actions brought

to redress the deprivation under color of state law of any

right, privilege or immunity secured by the Constitution 1

1 These Acts have been respectively codified in the Code of Virginia

at §§ 18-349.9 et seq., 18-349.17 et seq., 54-74, 78, 79, 18-349.25 et seq.,

and 18-349.31 et seq.

App. 2

or statutes of the United States providing for equal rights

of all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States.

Jurisdiction is also invoked under 28 U. S. C. §§1331 and

1332 wherein jurisdiction is conferred upon the federal

courts in all civil actions where the matter in controversy

exceeds the sum of $3,000 exclusive of interest and costs

and arises under the Constitution and law of the United

States or between citizens of different states. Accordingly,

the present three-judge district court was set up under 28

U. S. C. §2281 and evidence was taken upon which the

following findings of facts are based.

The National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People is a non-profit membership organization which

was established in 1909 and incorporated under the laws of

the State of New York in 1911. It is licensed to do business

as a foreign corporation in the State of Virginia. The pur

poses of the corporation are set out in the statement of its

charter:

“That the principal objects for which the corpora

tion is formed are voluntarily to promote equality of

rights and eradicate caste or race prejudice among the

citizens of the United States; to advance the interests

of colored citizens; to secure for them impartial suf

frage; and to increase their opportunities for securing

justice in the courts, education for their children, em

ployment according to their ability, and complete equal

ity before the law.

“To ascertain and publish all facts bearing upon

these subjects and to take any lawful action thereon;

together with any and all things which may lawfully

be done by a membership corporation organized under

the laws of the State of New York for the further

advancement of these objects.”

App. 3

The activities of the Association cover forty-four states,

the District of Columbia and the Territory of Alaska. It is

the most important Negro rights organization in the country

(see 6 Western Res. L. Rev. 101, 102; 58 Yale L. J. 574,

581), having approximately 1,000 uincorporated branches.

A branch consists of a group of persons in a local commu

nity who enroll the minimum number of members and upon

formal application to the main body are granted a charter.

In Virginia, there are eighty-nine active branches. A person

becomes a member of a branch upon payment of dues which

amount, at a minimum, to $2 per year and may be more at

the option of the member, up to the sum of $500 for life

membership. The regular dues of $2 per year are divided

into two parts, one-half being sent to the national office in

New York and one-half retained by the local branch.

In a number of states, including Virginia, the branches

are voluntarily grouped into an unincorporated State Con

ference, the expenses of which are paid jointly by the na

tional organization and the local branches, each contributing

10-cents out of its share of each member’s dues. In Virginia,

the branches contribute a greater sum for the support of

their State Conference.

The principal source of income of the Association and its

branches in the several states consists of the membership

fees which are solicited in local membership drives. Other

income is derived from special fund raising campaigns and

individual contributions. In the first eight months of the

year the greater number of annual membership drives are

conducted. During that period in 1957 the Association

enrolled 13,595 members in Virginia. This represents a

sharp reversal of the rising trend in membership figures in

the same eight-month period in the preceding three years,

which showed 13,583 members in 1954, 16,130 in 1955 and

19,436 in 1956. The income of the Association from its

App. 4

Virginia branches during the first eight months of 1957

was $37,470.60 as compared with $43,612.75 for the same

period in 1956. The total amount received by the Associ

ation from Virginia was $38,469.59 in the first eight months

of 1957 as compared with $44,138.71 for the same period in

1956. The total income of the Association from the country

as a whole for the year 1956 was $598,612.84 and

$425,608.13 for the first eight months of 1957.

At the top of the organizational structure of the national

body is the annual convention, which consists of delegates

representing the 1,000 branches in the several states. It has

the power to establish policies and programs for the ensuing

year which are binding upon the Board of Directors and

upon the branches of the Association. Each year the con

vention chooses sixteen members of a Board of forty-eight

Directors, each of whom serves for a term of three years.

The Board of Directors meets eleven times a year to carry

out the policies laid down by the convention. Under the

Board an administrative staff is set up, headed by an execu

tive secretary who, representing the Board, presides over the

functioning of the local branches and State Conferences

throughout the country under the authority of the constitu

tion and by-laws of the national body.

The Virginia State Conference takes the lead of the As

sociation’s activities in the state under the administration of

a full time salaried executive secretary, by whom the activi

ties of the branches in the state are co-ordinated and local

membership and fund raising campaigns are supervised.

The State Conference also holds annual conventions attended

by delegates from the branches, who elect officers and mem

bers of the Board of Directors of the Conference. Through

its representatives the State Conference appears before the

General Assembly of Virginia and State Commissions in

support of or in opposition to measures which in its view

App. 5

advance or retard the status of the Negro in Virginia. It

encourages Negroes to comply with the statutes of the state

so as to qualify themselves to vote, and it conducts educa

tional programs to acquaint the people of the state with the

facts regarding racial segregation and discrimination, and

to inform Negroes as to their legal rights and to encourage

the assertion of those rights when they are denied. In car

rying out this program, the public is informed of the policies

and objectives of the Association through public meetings,

speeches, press releases, newsletters and other media.

One of the most important activities of the State Confer

ence, perhaps its most important activity, is the contribution

it makes to the prosecution of law suits brought by Negroes

to secure their constitutional rights. It has been found,

through years of experience, that litigation is the most effec

tive means to this end when Negroes are subjected to racial

discrimination either by private persons or by public au

thority. Accordingly, the Virginia State Conference main

tains a legal committee or legal staff composed of thirteen

colored lawyers located in seven communities scattered over

the greater part of the state. The members of the legal staff

are elected at the annual convention of the State Conference

and they in turn elect a chairman. Ordinarily the legal staff

is called into action upon a complaint made to one or more

members of the staff by aggrieved parties, but sometimes a

grievance is brought directly to the attention of the Execu

tive Secretary of the Conference, and if in his judgment the

case presents a genuine grievance involving discrimination

on account of race or color, which falls within the scope of

the work of the Association, he refers the parties to the

Chairman of the legal staff. If the Chairman approves the

complaint, he recommends favorable action to the President

of the State Conference and if he concurs, the Conference

obligates itself to defray in whole or in part the costs and

App. 6

expenses of the litigation. With rare exceptions the attor

neys selected by the complainant to bring the suit have been

members of the legal staff. When a law suit has been com

pleted the attorney is compensated by the Conference for

out-of-pocket expenditures, including travel and steno

graphic services, and is also paid per diem compensation

for the time spent in his professional capacity. No money

ever passes directly to the plaintiff or litigant. The attorneys

appear in the course of the litigation for and on behalf of

the individual litigants, who in every instance authorize the

institution of the suit.

In brief, the Association, in various forms, publicizes its

policies against discrimination and informs the public that

it will offer aid for the prosecution of a legitimate complaint

involving improper discrimination. Thus it is generally

known that the State Conference will furnish money for

litigation if the proper need arises, but the Association does

not take the initiative and does not act until some individual

comes to it asking for help.

Sometimes a complainant seeks damages for violation of

his rights, as in cases involving the treatment accorded

Negroes in public conveyances. In such a case, the Associ

ation ordinarily does not furnish aid if the complainant is

financially able to prosecute his claim. In the most fruitful

field of litigation in respect to public education, the rights of

large numbers of colored people in the community are in

volved and a class suit is brought; and the Association pays

the expenses even if one or more of the complainants is

possessed of financial resources. In most of these cases the

expenses of the suit are so great that it could not be prose

cuted without outside aid. The fees paid the lawyers are

modest in size and less than they would ordinarily earn for

the time consumed.

The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

App. 7

Inc., the plaintiff in the second suit, also takes a prominent

part in support of litigation on behalf of Negro citizens. It

is a membership corporation which was incorporated under

the law of the State of New York in 1940. Like the Asso

ciation, the Fund is registered with the Virginia Corporation

Commission as a foreign corporation doing business in the

state. It was formed, as its name implies, to assist Negroes

to secure their constitutional rights by the prosecution of

law suits of the sort that have just been described. The

charter declares that its purposes are to render legal aid

gratuitously to Negroes suffering “legal injustice” by reason

of race or color who are unable on account of poverty to

employ and engage legal aid on their own behalf. Other

purposes are to secure educational facilities for Negroes

who are denied the same by reason of their race and color

and to conduct research and to compile and publish infor

mation on this subject and generally on the status of the

Negro in American life. The charter forbids the corpora

tion to attempt to influence legislation by propaganda or

otherwise and requires it to operate without pecuniary bene

fit to its members. The charter was approved by a New

York court after service upon and without objection from

the local bar association so that it obtained the right under

the law of New York to operate as a legal aid society.

The Fund is governed by a Board of Directors which,

under its charter, consists of not less than five and not more

than fifty members. Its work is directed by the usual execu

tive officers. It operates from an office in New York City

and has no subordinate units. It employs a full-time staff

of six resident attorneys and three research attorneys sta

tioned in New York City, and it keeps four lawyers on

annual retainers in Richmond, Dallas, Los Angeles and

Washington. It also engages local attorneys for investiga

App. 8

tion and research in particular cases. It has on call one

hundred lawyers throughout the country and a large number

of social scientists who operate on a voluntary basis and

work without pay or upon the payment of expenses only.

By virtue of its efforts to secure equal rights and oppor

tunities for colored citizens in the United States, the Fund

has become regarded as an instrument through which col

ored citizens of the United States may act in their efforts

to combat unconstitutional restrictions based upon race and

color.

In order to give information as to the nature of the work

of the Fund, members of the legal staff engage in public

speaking and lectures in colleges and universities through

out the country on a variety of subjects connected with the

legal rights of colored citizens and the race problem in gen

eral. But in conformity with the charter of the Fund, the

officers and employees of the corporation do not attempt to

influence legislation, by propaganda or otherwise.

It is apparent that so far as litigation is concerned the

purposes of the Association and of the Fund are identical,

and they in fact co-operate in this activity. They are, how

ever, separate corporate bodies with separate offices. At one

time some of the executive officers were in the employ of

both corporations but at the present no person serves as an

officer or employee, although many persons are members

of both bodies. The Fund was formed as a separate organi

zation because it was thought that it should have no part in

attempting to influence legislation and the complete separa

tion has been promoted by rulings of the Treasury Depart

ment, which disallow tax deductions for contributions to

organizations engaged in political activity. Deductions for

contributions to the Fund are allowed.

The revenues of the Fund are derived solely from con

App. 9

tributions received in response to letters sent out four times

a year throughout the country by the Committee of One

Hundred and, to some extent, from solicitations at small

luncheons or dinners. There are no membership dues. The

Committee of One Hundred was organized in 1941 by Dr.

Neilsen, former president of Smith College, and consists

predominantly of educators and lawyers who have joined

together for the purpose of raising the money necessary to

keep the organization going. Most of the money comes in

the form of $5 and $10 contributions. Substantial sums are

received from charitable foundations, of which the largest

was $15,000 and the aggregate was $50,000 in 1956. For

the four or five years prior to 1957 the income showed a

steady increase. The income for 1956 was $351,283.32.

For the first eight months of 1955, 1956 and 1957 the in

come was $152,000, $246,000 and $180,000, respectively.

The receipts from Virginia were $1,469.50 in 1954;

$6,256.19 in 1955, a portion of which was a refund from

prior litigation; $1,859.20 in 1956, and $424 for the first

eight months in 1957.

The total disbursements of the Fund for the year 1956

were $268,279.03. The total expenses for Virginia during

the past four years consisted principally of the sum of

$6 ,0 0 0 , which was the annual retainer of the regional

counsel.

The Fund supplements the work of the legal staff of the

Virginia State Conference by contributing the services of

the regional counsel and, more particularly, by furnishing

results of the research of scientists, lawyers and law pro

fessors in various parts of the country. The Fund also

contributes the very large expenditures which are needed

for the prosecution of important cases that go from the

federal courts in Virginia and other states to the Supreme

App. 10

Court of the United States in which the fundamental rules

governing racial problems are laid down. In this class of

case the expenses amount to a sum between $50,000 and

$100,000, and in the celebrated case of Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 6 8 6 , 98 L. Ed. 873, the

expenses amounted to a sum in excess of $200,000. The

expenses of cases tried in the lower courts, including an

appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Circuit, amount to

approximately $5,000.

The Fund has made only a superficial investigation into

the financial competency of complainants to whom it has

rendered aid in Virginia. For the most part the cases have

been class actions brought for the benefit of all the colored

citizens in a community with children in the local public

schools and the regional counsel of the Fund has entered the

cases at the request of members of the legal staff of the

State Conference. It has been obvious in such instances that

the burden of the litigation was too great for the individual

litigants to bear, and the lawyers for the Fund have not

regarded their participation as a violation of the charter

provision authorizing the Fund to aid indigent litigants even

if it was shown that some of the complainants in a case had

legal title to homes of substantial value.2

STATUTES IN SUIT

The five statutes against which the pending suits are

directed, that is Chapters 31, 32, 33, 35 and 36 of the Acts

2Testimony as to the activities of the Association and of the Fund

was given in large part by Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the

Association; Thurgood Marshall, director counsel of the Fund; W.

Lester Banks, executive secretary of the Virginia State Conference;

Oliver W. Hill, chairman of the legal staff of the Virginia State Con

ference ; Spottswood W. Robinson III, southeast regional counsel for

the Fund.

App. 11

of the General Assembly of Virginia, passed at its Extra

Session in 1956, were enacted for the express purpose of

impeding the integration of the races in the public schools

of the state which the plaintiff corporations are seeking to

promote. The cardinal provisions of these statutes are set

forth generally in the following summary.

Chapters 31 and 32 are registration statutes. They re

quire the registration with the State Corporation Commis

sion of Virginia of any person or corporation who engages

in the solicitation of funds to be used in the prosecution of

suits in which it has no pecuniary right or liability, or in

suits on behalf of any race or color, or who engages as one

of its principal activities in promoting or opposing the pas

sage of legislation by the General Assembly on behalf of

any race or color, or in the advocacy of racial integration

or segregation, or whose activities tend to cause racial con

flicts or violence. Penalties for failure to register in viola

tion of the statutes are provided.

Chapters 33, 35 and 36 relate to the procedure for sus

pension and revocation of licenses of attorneys at law, to the

crime of barratry and to the inducement and instigation of

legal proceedings. It is made unlawful for any person or

corporation: to act as an agent for another who employs

a lawyer in a proceeding in which the principal is not a party

and has no pecuniary right or liability; or to accept employ

ment as an attorney from any person known to have violated

this provision; or to instigate the institution of a law suit

by paying all or part of the expenses of litigation, unless the

instigator has a personal interest or pecuniary right or lia

bility therein; or to give or receive anything of value as an

inducement for the prosecution of a suit, in any state or

federal court or before any board or administrative agency

within the state, against the Commonwealth, its depart

App. 12

ments, subdivisions, officers and employees; or to advise,

counsel, or otherwise instigate the prosecution of such a

suit against the Commonwealth, etc., unless the instigator

has some interest in the subject or is related to or in a posi

tion of trust toward the plaintiff. Penalties for the violation

of these statutes are provided.

The legislative history of these statutes to which we now

refer conclusively shows that they were passed to nullify

as far as possible the effect of the decision of the Supreme

Court in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74

S. Ct. 6 8 6 , 98 L. Ed. 873 and 349 U. S. 294. 75 S. Ct. 753,

99 L. Ed. 1083.

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF

STATUTES IN SUIT

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 6 8 6 , 98 L. Ed. 873,

after argument and reargument, denounced the segregation

of the races in public education as a violation of the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and re

quested the parties as well as the attorneys general of the

affected states to file briefs and present further argument

to assist the court in formulating its decrees.3

On May 31, 1955, the Supreme Court, after further

argument, reaffirmed its position, reversed the judgments

below and remanded the cases to the lower courts to take

such proceedings as should be necessary and proper to

admit the parties to the public school on a racially non-

discriminatory basis with all deliberate speed.

3On the same day, in Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497, 74 S. Ct. 693,

98 L. Ed. 884, the Court held that segregation in the public schools in

the District of Columbia is a denial of the due process clause of the

Fifth Amendment.

App. 13

Amongst the cases in the group considered by the Su

preme Court was Davis v. County School Board of Prince

Edward County, Virginia, 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753,

99 L. Ed. 1083, which was instituted on May 23, 1951, on

behalf of colored children of high school age in that county.

The case had been tried by a three-judge district court after

the Commonwealth of Virginia had been permitted to inter

vene. The court upheld the validity of the constitutional and

statutory enactments of the state which required the segre

gation of the races in the state schools but found that the

buildings, curricula and transportation furnished the colored

children were inferior to those furnished the white children

and ordered the defendants to remedy the defects with dili

gence and dispatch. 103 F. Supp. 337. As we have seen,

this decision was reversed by the Supreme Court on the

constitutional point and the duty to eliminate segregation

was directly presented to the State authorities.4 Their re

action is depicted in the following recital.

On August 30, 1954, the Governor of Virginia appointed

the Gray Commission on Public Education, composed of

thirty-two members of the General Assembly, and directed

it to study the effect of the segregation decisions and make

such recommendations as might be deemed proper. The

Commission submitted its final report to the Governor on

November 11, 1955. Referring to prior decisions of the

Supreme Court and to the non-judicial authority cited by

it in support of the segregation decision, the Commission

characterized the latter in the following terms:

4 On remand, after the filing of numerous motions and the rendering

of arguments thereon, the Court entered a decree enjoining racial dis

crimination in school admission but refused to set a time limit within

which the Board should begin compliance, observing the likelihood of

the schools being closed under state law. D. C., 149 F. Supp. 431. This

refusal was reversed on appeal, Allen v. County School Board of

Prince Edward County, Va., 4 Cir., 249 F. 2d 462.

App. 14

“With this decision, based upon such authority, we

are now faced. It is a matter of the gravest import, not

only to those communities where problems of race are

serious, but to every community in the land, because

this decision transcends the matter of segregation in

education, [emphasis added] It means that irrespective

of precedent, long acquiesced in, the Court can and will

change its interpretation of the Constitution at its

pleasure, disregarding the orderly processes for its

amendment set forth in Article V thereof. It means

that the most fundamental of the rights of the states

and of their citizens exist by the Court’s sufferance and

that the law of the land is whatever the Court may

determine it to be by the process of judicial legislation.”

The Commission’s general conclusion was that “separate

facilities in our public schools are in the best interest of

both races, educationally and otherwise, and that compulsory

integration should be resisted by all proper means in our

power”. To this end the Commission recommended that a

special session of the General Assembly be called to author

ize the holding of a constitutional convention in order to

amend § 141 of the Constitution of Virginia which shortly

before had been held by the Supreme Court of Appeals of

Virginia in Almond v. Day, 197 Va. 419, 89 S. E. 2d 851,

to prohibit the payment of tuition and other expenses of

students who may not desire to attend public schools. The

Commission also recommended that legislation be passed

conferring broad discretion upon the school authorities to

assign pupils in the public schools and to provide for the

expenditure of State funds in the payment of tuition grants

so as to prevent enforced integration. In response to this

recommendation, the General Assembly, on December 3,

1955, meeting in Extra Session, enacted a bill, submitting

App. 15

to the voters of the state the question whether such a con

vention should be held, and on January 9, 1956, the holding

of the convention was approved by the voters.

On February 1, 1956, the General Assembly in its regular

session adopted an “interposition resolution” by votes of

36-to-2 in the Senate and 90-to-5 in the House of Delegates.

In this resolution the following declarations were included:

“That by its decision of May 17, 1954, in the school

cases, the Supreme Court of the United States placed

upon the Constitution an interpretation, having the

effect of an amendment thereto, which interpretation

Virginia emphatically disapproves; * * *

“That with the Supreme Court’s decision aforesaid

and this resolution by the General Assembly of Vir

ginia, a question of contested power has arisen: The

court asserts, for its part, that the States did, in fact,

in 1868, prohibit unto themselves, by means of the

Fourteenth Amendment, the power to maintain racially

separate public schools, which power certain of the

States have exercised daily for more than 80 years; the

State of Virginia, for her part, asserts that she has

never surrendered such power;

“That this declaration upon the part of the Supreme

Court of the United States constitutes a deliberate,

palpable, and dangerous attempt of the court itself to

usurp the amendatory power that lies solely with not

fewer than three-fourths of the States; * * *

“That Virginia, anxiously concerned at this massive

expansion of central authority, * * * is in duty bound

to interpose against these most serious consequences,

and earnestly to challenge the usurped authority that

would inflict them upon her citizens. * * *

“And be it finally resolved, that until the question

App. 16

here asserted by the State of Virginia be settled by

clear Constitutional amendment, we pledge our firm

intention to take all appropriate measures honorably,

legally and constitutionally available to us, to resist

this illegal encroachment upon our sovereign powers,

and to urge upon our sister States, whose authority

over their own most cherished powers may next be im

periled, their prompt and deliberate efforts to check

this and further encroachment by the Supreme Court,

through judicial legislation, upon the reserved powers

of the States.” Acts 1956, pp. 1213, 1214.

The constitutional convention authorized by the voters

was held on March 7, 1956, and amended § 141 of the con

stitution of the state in accordance with the recommendation

of the Gray Commission.

On August 27, 1956, the General Assembly was convened

in Extra Session in response to the call of the Governor of

the State. He made an opening address to the assembled

lawmakers,5 in the course of which he said:

“The people of Virginia, and their elected repre

sentatives, are confronted with the gravest problems

since 1865. Beginning with the decision of the Supreme

Court of the United States on May 17, 1954, there has

been a series of events striking at the very fundamen

tals of constitutional government and creating situ

ations of the utmost concern to all our people in this

Commonwealth, and throughout the South.

“Because of the events I have just mentioned, 1 come

5 Sec. 73 of the Virginia Constitution provides: “The Governor

shall * * * recommend to (the General Assembly’s) consideration

such measures as he may deem expedient, and convene the General

Assembly * * * when, in his opinion, the interest of the State may

require.”

App. 17

before you today for the purpose of submitting rec

ommendations to continue our system of segregated

public schools * * *

“The principal bill which I submit to you at this

time defines State policy and governs public school

appropriations accordingly. The declaration reads, in

part, as follows:

“ ‘The General Assembly declares, finds and estab

lishes as a fact that the mixing of white and colored

children in any elementary or secondary public school

within any county, city or town of the Commonwealth

constitutes a clear and present danger * * * and that

no efficient system of elementary and secondary public

schools can be maintained in any county, city or town

in which white and colored are taught in any such

school located therein.’

“The bill then defines efficient systems of elementary

and secondary public schools as those systems within