Jackson v. Marvell School District Petition for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

October 16, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. Marvell School District Petition for Rehearing, 1969. af2e2df2-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/090d92e5-9b68-42b3-8292-5b1cdcb335a6/jackson-v-marvell-school-district-petition-for-rehearing. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

-P C

N

BuTXGaqa'H xoq sa3UOTq.xq.ad

-squaxxoddv xoq sAauxoqqv

109TL s u s u g^x v 'jjuqa auxa

qaaxqs u x bW %6Z£

*HT J CIHYMOH 3DH0H0

OZZL SGSUGqav ŷ ooH e x w a

eexqs xtquaaqaxqi, qsaM 0Z8T

AHHaaNaicm *o anna

H3>IrIVM *M nhop

6I00T >t̂ OA m-SN 'qaoA aasn exoaxo snqumxoD oi

NIMHDVHO T NVWHOM DxiaaNaano >iov.e

oNiavanaa noa MOiiiiad

uotstatq uiaissa 'sesue^iv qo qoxxqsxa uxaqsaH sui, aoj

qxnoo qoxxqsxci seqaqs paqxun eqj. uioxa s[uaddv

• saaxiedd^f

" X u q s ‘ZZ °CN iO IH C L S ia dOOHOS TT3AHVW

* SA

'squGXIsddv "XU qa 'NOSHDVr SHHNiaO

pue

'saaxiaddv

" X U qa '^ 2 *0N &0IHISICI rI00HDS TI3AHYW

•SA

■'squuxX'Uddy

" x u qa axosMoar srrava

L6L6T * ON 9 9W.6T *0N

iinoaio iLinoia 3Hi noa

savaddv/ ao annoo sa.i.vis aaj.iNn 3HJ. ni

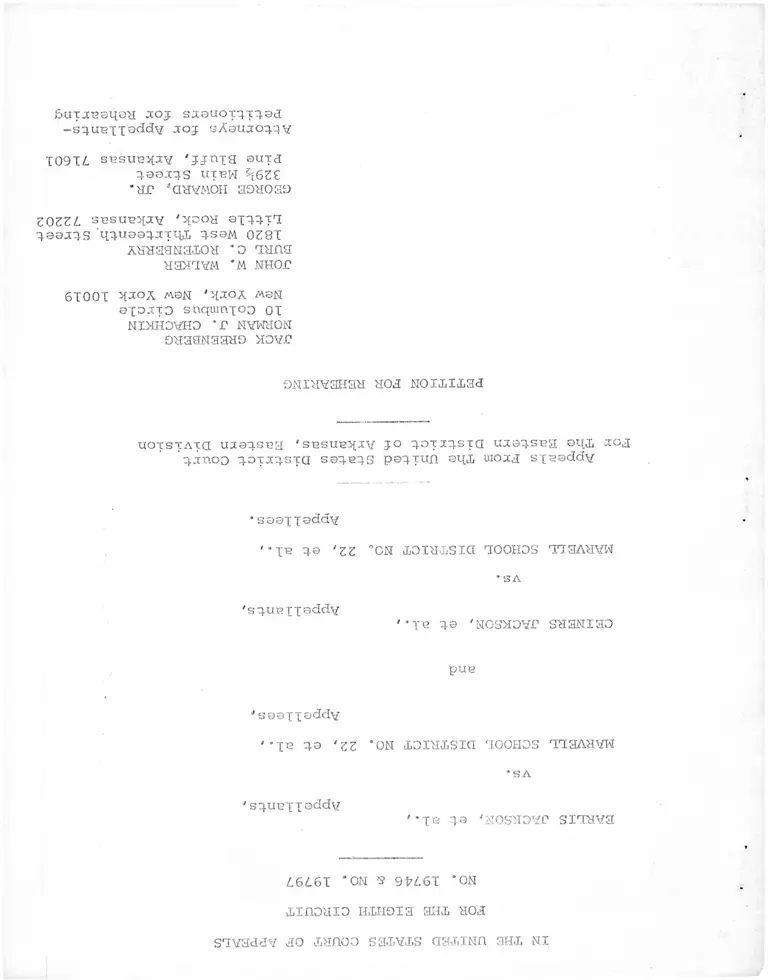

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 19746 & NO. 19797

EARLIS JACKSON, et al., Appellants,

vs.

MARVELL SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 22, et al.,

Appellees,

and

CEINERS JACKSON, et al.. Appellants,

vs.

MARVELL SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 22, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeals From The united States District Court

For The Eastern District of Arkansas, Eastern Division

PETITION FOR REHEARING

Appellants respectfully pray that this Court set this

matter down for rehearing in order to reconsider the Court s

denial of any award of attorneys' fees in its October 2 opinion.

We invite the Court's careful consideration of the matter,

apart from the merits of the case, which have been determined.

I

The question whether attorneys' fees should be awarded to

the prevailing party may reach an appellate court in several

different postures: in an appeal from the denial of such an

award by the district court (which may be joined with other

issues, as where the district court ruled against the appellant

on the merits, or raised alone, as where the appellant prevailed

below); in an appeal by the unsuccessful district court litigant

against whom attorneys' fees were taxed; finally, as a request by

a party to a pending appeal (grounded upon the equity jurisdiction

of the court or upon the provisions of the Federal Rules of

Appellate procedure) that the reviewing court itself render an

award of counsel fees incident to its disposition of the appeal.

Several courses are available to the appellate court. As

to a claim for counsel fees in the district court, it can itself

make an award of fees covering this aspect of the litigation.

See Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14, 23 (8th Cir. 1965). It may

require the district court to make an award on remand; it can

suggest that the district court's discretion be favorably exer

cised; it can leave the matter entirely to the discretion of the

district court. As to requests for counsel fees on the appeal

itself, they may be either granted or denied without comment or

with some explanation of the court's action. In any event, the

court's inherent authority to make the award goes beyond the

limited case of frivolous appeals covered by Rule 38 of the

Federal Rules of Appellate procedure.

-2-

Although en banc hearing of a case ought provide an opportunity

for the full court to express its views definitively, the matter

of attorneys' fees is disposed of in one short sentence in this

Court's October 2 opinion. We suggest the appropriateness of

reconsideration in this instance for two reasons. First, summary

disposition of the application for counsel fees was probably

occasioned by the overriding importance of issues going to the

merits — illustrated by the immediate issuance of this Court's

mandate and the granting of midyear relief. Indeed, discussion

of the merits occupied the entire oral argument, at which neither

party argued the counsel fees point.

Second, and more crucial, summary denial in the October 2

opinion of the application for.an award of counsel fees for

services in both the district court and the Court of Appeals is

tantamount to judicial endorsement of this school district's

utter disregard for law. This was an appeal by plaintiffs in a

school desegregation action, who had objected unsuccessfully to

continuation of the free choice procedure of pupil assignment.

Thus as to the orders appealed from, there was no occasion for

the district court to render an award of counsel fees in favor

of plaintiffs, who had not prevailed on the merits. But this

Court's summary rejection of the claim, rather than at least

remanding to the district court on this issue, amounts to holding

that in the circumstances of this case, it would have been an

abuse of discretion for the district court to have awarded counsel

fees to plaintiffs had that court ruled in their favor. We

cannot believe the Court intended that result.

-3-

II

We start with the proposition — often submerged in the

concentration upon the mechanics of school district assignment

methods in the last few years — that these suits are brought

to vindicate rights guaranteed by- the oldest and most cherished

law of this nation, the Constitution of the united States.

They are brought to make government itself — the guarantor

and enforcer of the law — respect the law. This Court recog

nized the illogic of the situation three years ago in Clark v.

Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 369 F.2d 661, 671 (8th Cir. 1966)

when it referred to "unwilling victims of illegal discrimination

[who must] bear the constant and crushing expense of enforcing

their constitutionally accorded rights."

This Court, no less than the district courts do, bears a

responsibility to see that the mandates of the Constitution of

the United states are enforced and obeyed. The history of

school desegregation cases in this circuit indicates that these

Constitutional mandates are not being obeyed. Time after time,

school district upon school district has returned to this Court

to be told yet again to shoulder its responsibility to end

discrimination: Little Rock, El Dorado, Dollarway and now Marvell.

The pattern is fated to continue so long as the cost of defiance

is so small. As disheartening as it may seem, the fact is that

monetary penalties will more likely produce constitutional com

pliance-̂ than appeals to moral principle or legal-duty. This

1/ This Court has demonstrated that concepts of policy may shape

the determination whether to award or deny attorneys' fees,

as in Kemp v. Beasley, 389 F.2d 178, 191 (8th Cir. 1968), where

fees were denied "[p]ointing toward a more cooperative atmosphere

-4

Court implicitly took account of this in Clark, supra, in

referring to the "additional sanction" of awarding substantial

attorneys' fees.

The generally accepted rule is that an award of counsel

fees in district court proceedings is entirely discretionary

with the district court. Thus, this Court has on several occa

sions in school desegregation cases declined to require a larger

award than had been made by the district court. E .g., Clark v.

Board of Educ, of Little Rock, supra; Cato v. Parham, 403 F.2d

12 (8th Cir. 1968). The Court has also upheld the exercise of

the district court's discretion to withhold an award of fees.

2/Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965).—

We think it completely within the Court's power to alter

that rule in school desegregation cases. But at the least the

boundaries of the district court's discretion should be given

clearer definition. In this case, we submit that an abuse of

discretion would occur if the district court v/ere to deny

reasonable attorneys' fees to the Negro plaintiffs. It is unnec

essary to review again the long history of this litigation. The

conduct of the Marvell School district in the last year alone

and in balancing all circumstances. . . . " C f. Kemp v. Beasley,

352 F.2d 14, 23 (8th Cir. 1965): "The court would have the

power sitting as a court of equity to impose sanctions necessary

to effectuate its decrees and to punish conduct and tactics of

parties that are discreditable. . . . "

2/ The distinction between Kemp [1965 case] and this case is

critical. There, the district court had indeed exercised its

discretion. Granting partial relief to the plaintiffs, it had

denied attorneys' fees but explicitly taxed costs against the

school district. In this case no discretion may be said to have

been invoked, since plaintiffs-appellants did not prevail below

-5-

amply compels the "additional sanction" of attorneys fees.

While

[p]rior to the decisions in the trilogy

of Green cases, the Supreme Court had not

explicitly determined the constitutional

effectiveness of freedom-of-choice

desegregation plans [October 2 slip opinion

at p. 6] ,

the law was perfectly clear in February, 1969 when this school

district deliberately violated the order of the district court

to come forward with a plan other than freedom of choice:

instead of filing a plan as directed by

the court, the appellees filed a report

on February 3, 1969, in which they took

issue with the court's prior order [October

2 slip opinion at p. 5].

Is this not "obstinate, adamant, and open resistance to the

law?" Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, supra. Must

appellants' class, the "unwilling victims of illegal discrimin

ation, " pay for such resistance on the part of the officials

of the school district not only by additional delay in imple

menting their constitutional rights, but also by being forced

to bear "the constant and crushing expense" of litigation?

Appellants pray that this Court grant rehearing and award

substantial counsel fees on appeal and in the district court.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG/

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

and in such circumstances the district court could not have awarded

fees to plaintiffs under any concept of discretion. Once this Court

held the district court erred, the question of counsel fees was

infused with a new imperative.

-6

JOHN W. WALKER

BURL C. ROTENBERRY 1820 West Thirteenth Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72202

GEORGE HOWARD, JR.

329^ Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas 71601

Attorneys for Appellants-

petitioners for Rehearing

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that on the 16th day of October, 1969,

I served a copy of the foregoing petition for Rehearing herein

_ Jupon counsel for appellees, Robert V. Light, Esq., 1100 Boyle

Building, Little Rock, Arkansas 72201 and Charles B. Roscopf,

Esq., 417 Rightor Street, Helena, Arkansas 72342, by United

States mail, first class postage prepaid.

Attorney for Appellants-

Petitioners/for Rehearing

-7-