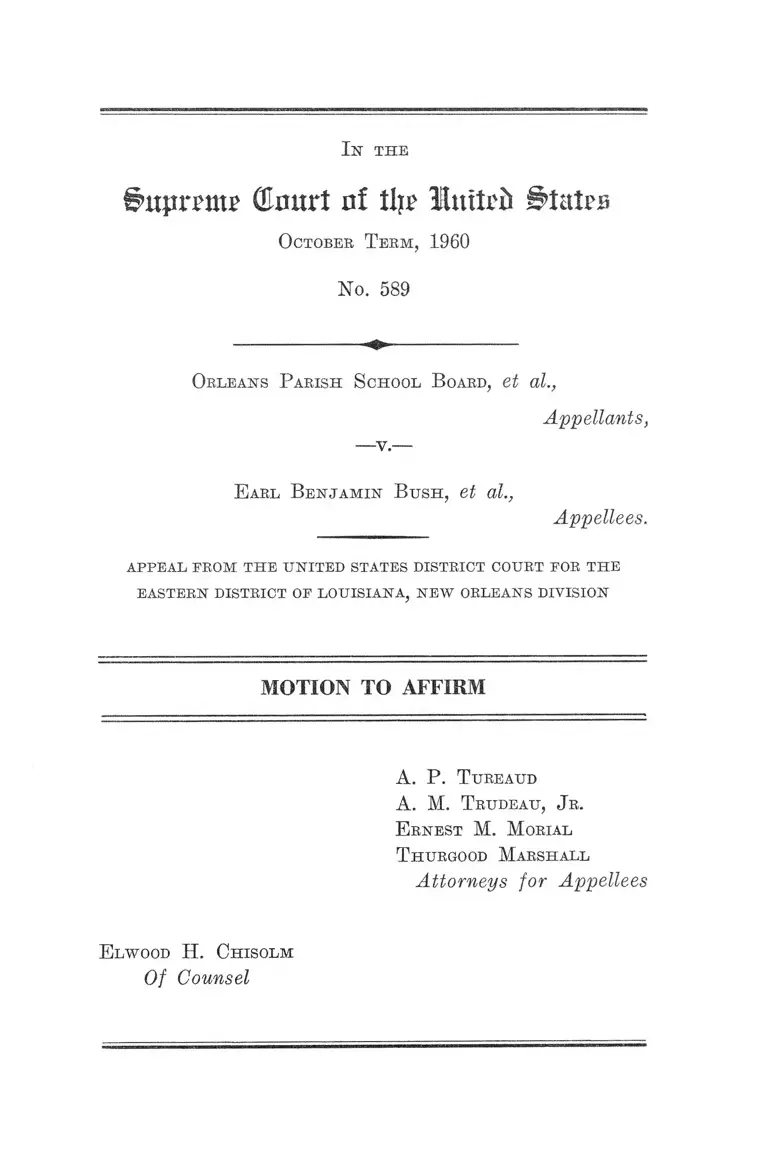

Orleans Parish School Board v Bush Motion to Affirm

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Orleans Parish School Board v Bush Motion to Affirm, 1960. 45a6fb16-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/09901635-4acc-4f32-bb9b-3b30cf148006/orleans-parish-school-board-v-bush-motion-to-affirm. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

iatpriw (ta rt nf tljr Huitrii i>tatrB

O ctober T erm, 1960

No. 589

1st th e

Orleans Parish S chool B oard, et al.,

Appellants,

— v .-

E arl Benjam in B hsh , et al.,

Appellees.

a p p e a l p r o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t p o r t h e

EASTERN DISTRICT OP LOUISIANA, NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

MOTION TO AFFIRM

A. P. T ureaud

A. M. T rudeau, Jr.

E rnest M. M orial

T hurgood M arshall

Attorneys for Appellees

E lwood H. Chisolm

Of Counsel

I n the

(Hxmxt of flj? Unltxb

O ctober T eem , 1960

No. 589

Orleans P aeish S chool B oaed, et al.,

Appellants,

E ael B e n ja m in B u sh , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FBOM THE UNITED STATES DISTBICT COURT FOE THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA, NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

MOTION TO AFFIRM

Appellees move to affirm the judgment below on the

ground that it is manifest that the questions on which the

decision of the cause depends are so unsubstantial as not to

need further argument.

Questions Presented

For the purposes of this motion, appellees adopt the

questions presented by appellants at pages 3-4 of their

Jurisdictional Statement.

Statement o f the Case

The complete history of this protracted litigation, in

cluding a full statement of the proceedings giving rise to

2

this appeal, is set out in the opinion of the court below.

See Appellants’ Jurisdictional Statement, Appendix A

(pp. 17 et seq.).

Reasons for Granting the Motion

Appellants, the Orleans Parish School Board, four of

its five elected members and the Parish Superintendent

of Schools, formally tender five questions on this appeal.

Although the validity of “ a packet of segregation measures”

has been variously drawn in question by four of the five

questions presented, appellants nonetheless concede that

“ all of the[se] statutes and resolutions . . . are patently

unconstitutional and pose no substantial constitutional

question” (Juris. Statement, pp. 10, 11). Such concession,

appellees agree, is compelled by Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 347 U.S. 483; Id., 349 U.S. 294, 298; Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1; United States v. Louisiana, 29 U.S. L.

Week 4061 (U.S. December 12, 1960); Aaron v. McKinley,

173 P.Supp. 944 (E.D. Ark. 1959), affirmed sub nom.

Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197; James v. Almond, 170

F.Supp. 331 (E.D. Va. 1959), dismissed 359 U.S. 1006;

James v. Duclavorth, 170 F.Supp. 342 (E.D. Va. 1959),

affirmed 267 F.2d 224 (4th Cir. 1959), cert, denied 361

U.S. 835.

“However,” appellants assert, “ the denial of the District

Court of Appellants’ motion to allow it to continue the

operation of segregated schools in the Parish of Orleans,

while the State of Louisiana pursues its attempt to assert

the supremacy of its sovereignty over the Federal Courts,

does present questions which are so substantial as to re

quire plenary consideration” (Juris. Statement, p. 11).

Appellees submit that this question has already been settled

by this Court in Cooper v. Aaron, supra, and therefore, is,

3

so devoid of merit that the decision below on this aspect

of the case should also be allowed to stand without plenary

consideration. Moreover, appellees adopt the following sec

tion of the opinion below (Juris. Statement, Appendix A,

pp. 37-38); and we suggest that it fully disposes of the

argument renewed here by appellants:*

M o t io n to V a c a t e

The last matter presented for our consideration is

the School Board’s plea that we postpone the effective

date of the order compelling desegregation of first

grade classes by November 14. The Board suggests

that local conditions are so disturbed that orderly com

pliance is difficult at this time, especially in view of

its own precarious legal and financial position. All

this may be true, but the history of this litigation

leaves some doubt about the advisability of further

postponing an inevitable deadline. Indeed, the date

originally set for making a start in the direction of

desegregation has already been postponed two months

and it is far from clear that this delay improved con

ditions. But, in any event, though we be persuaded of

the School Board’s good faith, there can be no question

of delaying still longer the enjoyment of a constitu

tional right which was solemnly pronounced by the

Supreme Court of the United States more than six

years ago. As that Court itself said in rejecting a

similar plea in Cooper v. Aaron, supra, 15-16;

“ One may well sympathize with the position of the

Board in the face of the frustrating conditions

which have confronted it, but, regardless of the

Board’s good faith, the actions of the other state

agencies responsible for these conditions compel us

* See also Bush v. Orlans Parish School Board, Civ. No. 3630, E. D. La.,

December 21, 1960.

4

to reject the Board’s legal position. Had Central

High School been under the direct management of

the State itself, it could hardly be suggested that

those immediately in charge of the school should

be heard to assert their own good faith as a legal

excuse for delay in implementing the constitutional

rights of these respondents, when vindication of

those rights was rendered difficult, or impossible by

the actions of other state officials. The situation

here is in no different posture because the members

of the School Board and the Superintendent of

Schools are local officials; from the point of view of

the Fourteenth Amendment, they stand in this liti

gation as the agents of the State.

“ The constitutional rights of respondents are not

to be sacrificed or yielded to the violence and dis

order which have followed upon the actions of the

Governor and Legislature. As this Court said some

41 years ago in a unanimous opinion in a case in

volving another aspect of racial segregation: ‘It is

urged that this proposed segregation will promote

the public peace by preventing race conflicts. Desir

able as this is, and important as is the preservation

of the public peace, this aim cannot be accomplished

by laws or ordinances which deny rights created or

protected by the Federal Constitution.’ Buchanan

v. Warley, 245 H.S. 60, 81. Thus, law and order are

not here to be preserved by depriving the Negro

children of their constitutional rights. The record

before us clearly establishes that the growth of the

Board’s difficulties to a magnitude beyond its un

aided power to control is the product of state action.

Those difficulties as counsel for the Board forth

rightly conceded on the oral argument in this Court,

can also be brought under control by state action.”

5

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the questions presented by

appellants are clearly unsubstantial and this motion to

affirm should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

A. P. T ureaud

A. M. T rudeau, Jr.

E rnest M. M orial

T hurgood M arshall

Attorneys for Appellees

E lwood H. Chisolm

Of Counsel

< * & t ° 38