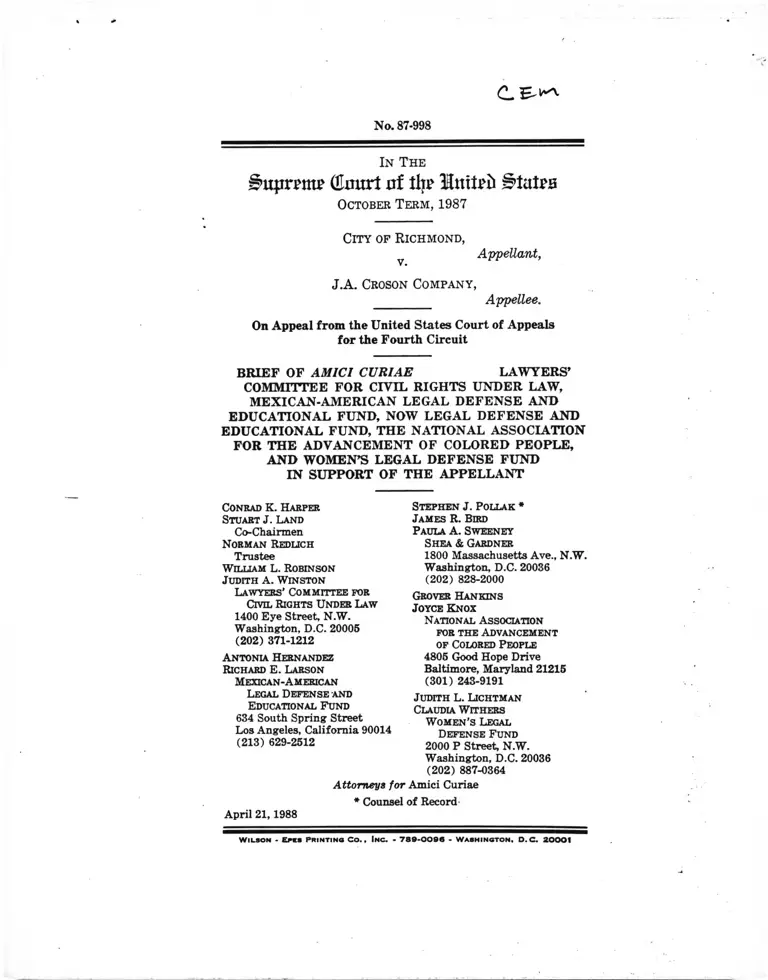

Richmond v JA Croson Company Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Appellant

Public Court Documents

April 21, 1988

26 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Richmond v JA Croson Company Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Appellant, 1988. e1e4af3d-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/09aa17de-edcf-4db6-8459-a3ab7a3e2157/richmond-v-ja-croson-company-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 87-998

I n T h e

£>upn?ttu> (Enurt of tip United States

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1987

C i t y o f R i c h m o n d ,

Appellant,

J.A. C r o s o n C o m p a n y ,

___________ Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE LAW YER S’

COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW,

M EXICAN -AM ER ICAN LEGAL DEFEN SE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, NOW LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, THE N ATIONAL ASSOCIATION

FOR TH E ADVANCEM ENT OF COLORED PEOPLE,

A N D W OM EN’S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

IN SUPPORT OF THE APPELLANT

Conrad K. Harper

Stuart J. Land

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

W illiam L. Robinson

Judith A . W inston

Lawyers ’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N .W .

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

A ntonia Hernandez

Richard E. Larson

Mexican-A mekican

Legal Defense and

Educational Fund

634 South Spring Street

Los Angeles, California 90014

(213) 629-2512

Stephen J. Pollak *

James R. Bird

Paula A . Sweeney

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Ave., N .W .

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

Grover Han kin s

Joyce Knox

National A ssociation

for the Advancement

of Colored People

4805 Good Hope Drive

Baltimore, Maryland 21215

(301) 243-9191

Judith L. Lichtman

Claudia W ithers

W omen 's Legal

Defense Fund

2000 P Street, N .W .

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 887-0364

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

April 21,1988

* Counsel of Record-

W il s o n - E>es p r in t in g C o . , In c . - 7 8 0 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h in g t o n , D .C . 2 0 0 0 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................................

INTEREST OF AMICI C U R IA E ......................................

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ...........................................

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGU

MENT .............................................................

AR GU M ENT...............................................................

I. THE CONSTITUTION DOES NOT FORBTD

STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS FROM

TAKING RACE-CONSCIOUS ACTION TO

CURE DISCRIMINATION AND ITS EF

FECTS IN INDUSTRIES WITH WHICH

THEY DO BUSINESS .............................

A. State and Local Governments, Like Con

gress, May Constitutionally Undertake A f

firmative Action to Cure the Effects of Past

Discrimination Whether or Not They Have

Participated in Such Discrimination

B. State and Local Governments Participate

in Discrimination When They Award Con

tracts to a Construction Industry Charac

terized by Discrimination ..................................

II. THE FOURTH CIRCUIT IMPROPERLY

HELD THAT RICHMOND HAD NO FIRM

BASIS FOR BELIEVING REMEDIAL AC

TION W AS REQUIRED .........................................

A. The District Court’s Finding that the City

Had Adequate Support for Believing that

Its Public Contracting Awards Were Per

petuating Effects of Discrimination Should

Be Sustained......................................

B. The Council Had a Reasonable Basis to Be

lieve that the City Itself Had Discrimi

nated ................................

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS— Continued

Page

III. THE RICHMOND PLAN IS NARROWLY

TAILORED TO ACHIEVE ITS REMEDIAL

GOAL OF ENDING RACIAL EXCLUSION IN

PUBLIC CONTRACTING........................................ 24

A. The City Council Considered Alternatives. 25

B. The Set-Aside Program Is Limited in Dura

tion ................................................................... 26

C. The Council Selected a Reasonable Figure

for the Set-Aside Percentage.................................. 26

D. The Richmond Plan Provides for an Ade

quate Waiver .......................................... 27

E. The Burden on Non-Minorities Is Consistent

with Fundamental Fairness................................... 28

CONCLUSION.......................................................................... 30

m

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases; Page

Anderson v. Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564 (1985). 18

Assoc. Gen. Contr. of Cal. v. City & County of

San Francisco, 818 F.2d 922 (9th Cir. 1987) 12

Board of Directors of Rotary International v.

Rotary Club of Duarte, 107 S. Ct. 1940 (1987). 14

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, Virginia,

345 F.2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965), vacated on pro-

cedural grounds, 382 U:S. 103 (1965) .......... ...... 3

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, Virginia,

462 F.2d 1058 (4th Cir. 1972), aff’d, 412 U s ’

92 (1973) ........................................... ‘ 24

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority 365

U.S. 715 (1961) .......................... ' 15

Carson v. American Brands, Inc., 606 F.2d 420

(4th Cir. 1979), rev’d, 450 U.S. 79 (1981)........ 3

City of Richmond v. United States, 422 U S 858

(1975) ................................................................... '........ 24

City of Rome v. United States, 446 U S 156

(1980) ............................................................................... 14

Constructors Assoc, of Western Pa. v. Kreps, 441

F. Supp. 936 (W.D. Pa. 1977), aff’d, 573 F.2d

811 (1978) .................................................................... 26

Denton v. International Broth, of Boilermakers,

650 F. Supp. 1151 (D. Mass. 1986)................. ....’ 22

Ethridge v. Rhodes, 268 F. Supp. 83 (S.D Ohio

w 1967) ................................................................................ 14-15

Evans v. Laurel Links, Inc., 261 F. Supp 474

(1966) .................................................. 3

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co. 424 U S

747 (1 97 6 )............................................. ....................' ; 24

Fullilove v. Kreps, 584 F.2d 600 (2d Cir. 1978),

aff’d sub nom. Fidlilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S.'

448 (1980) .................................................................... passim

Grant v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 635 F.2d 1007

(2d Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 452 U.S. 940

(1981) ............................................................................. 22

/ . A. Croson Co. v. City of Richmond, 779 F.2d

181 (4th Cir. 1985), vacated and remanded,

106 S.Ct. 3327 (1986), on remand, 822 F 2d

1355 <!987) ..................................................................PaSSim

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Johnson v. Transp. Agency, Santa Clara Cty.,

Cal., 107 S. Ct. 1442 (1987) ...................................passim

Local 28 of Sheet Metal Workers V. E.E.O.C., 478

U.S. 421, 106 S. Ct. 3019 (1986)........................... 5

Local Number 93 v. City of Cleveland, 478 U.S.

501, 106 S. Ct. 3063 (1986)..................................... 5

Local Union No. 85, Etc. V. City of Hartford,

625 F.2d 416 (2d Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 453

U.S. 913 (1981) ............................................................ 22

Michigan Road Builders Ass’n, Inc. V. Milliken,

834 F.2d 583 (6th Cir. 1987) ................................... 12

National Black Police Ass’n, Inc. v. Velde, 712

F.2d 569 (D.C. Cir. 1983) cert, denied, 446 U.S.

963 (1984) .................................................................... 15

Ohio Contractors Ass’n v. Keip, 713 F.2d 167 (6th

Cir. 1983) ....................................................................... 18

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 634 F.2d 744

(4th Cir. 1980), vacated, 456 U.S. 63 (1982) .... 3

Percy v. Brennan, 384 F. Supp. 800 (S.D. N.Y.

1977) ................................................................................ 15

Pullman-Standard V. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982).. 18,24

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Incorporated, 279 F.

Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968) ......................................... 3

Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609

(1984) ................ 14

Schmidt v. Oakland Unified School Dist., 662 F.2d

550 (9th Cir. 1981), vacated and rev’d, 457

U.S. 594 (1982) ....................................................13,20,27

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301

(1966)............................................................................... 14

South Fla. Chap. v. Metropolitan Dade County,

Fla., 723 F.2d 846 (11th Cir.), cert, denied, 469

U.S. 871 (1984) .....’...................................................... 20,27

Southwest Washington Chapt., Nat’l Elec. Contr.

Assn. v. Pierce Cty., 667 P.2d 1092 (Wash.

1 98 2)................................................................................. 18, 27

Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193 (1979)........passim

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) .. 19-20

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U S

144 (1 9 7 7 ).................................................................... ' 6

v

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

United States v. Paradise, 107 S. Ct. 1053 (1987)..passim

University of California Regents v. Balcke, 438

U.S. 265 (1978)............................................................ passim

Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education, 476 U.S.

267 (1986) .................................................................... passim

Constitutions, statutes, and regulations :

U.S. Const, amend. X I V ................................................... passim

Public Works Employment Act of 1977, Pub. L.

No. 95-28, § 103(f) (2 ), 91 Stat. 116, 117 (codi

fied at 42 U.S.C. § 6705(f) (2) (1982)) ...... 2

F.R. Civ. P. 52(a) .................... is

45 Fed. Reg. 65976 et seq. (Oct. 3, 1 98 0).................... 21, 27

Virginia Public Procurement Act, § 11-48, Va.

Code Ann. § 11-48 (1984) ................. 5

Human Rights, Richmond, Va., Code § 17.2

(1975) ............................................................................. 5

Minority Business Utilization Plan, § 27.10-20, art.

VIII-A, Richmond, Va., Ordinance 83.69-59

(April 11, 1983) ................................. ...passim

Miscellaneous:

Schnapper, Affirmative Action and the Legisla

tive History of the Fourteenth Amendment,

71 Va. L. Rev. 753 (1985) 13

In T h e

&u|ir?m? dmtri uf % Muitrii &fatra

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1987

No. 87-998

C it y o f R i c h m o n d ,

v Appellant,

J.A. C r o so n C o m p a n y ,

_________ Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE LAW YERS’

COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW,

MEXICAN-AM ERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, NOW LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION

FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE,

AND WOMEN’S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

IN SUPPORT OF THE APPELLANT

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE1

The five amici curiae who submit this brief2 * have of

ten appeared in this Court, both as amici and on behalf

of minorities and women, in civil rights cases involving

discrimination in voting, education, employment and

housing. They have a direct interest in supporting the

principle that, consistent with the Equal Protection

Clause, state and local governments may establish reme-

1 Pursuant to Rule 36.2, written consents of the parties to the

submission of this brief have been filed with the Clerk of the Court.

0 A description of each amicus organization is set forth in Ap

pendix No. 1.

2

dial programs to eradicate discrimination and the contin

uing effects of prior discrimination. The experience of

the amici in a broad range of discrimination and affirma

tive action litigation may enable amici to illuminate for

the Court some of the issues presented by this case.

STATEM ENT OF THE CASE

This case involves the constitutionality of the Minority

Business Utilization Plan adopted by the City of Rich

mond.3 We generally adopt the statement of the case pro

vided by Richmond in its brief. What follows represents

an amplified description of the City Council proceedings

leading to adoption of the plan.

In 1977, the Congress adopted a Minority Business En

terprise ( “ MBE” ) set-aside plan as part of the Public

Works Employment Act of 1977. 42 U.S.C. § 6705(f) (2)

(1982). This statute required state and local government

applicants for federal public works funds to guarantee

that 10% of the funds would be expended through MBEs.

Shortly thereafter, this Court upheld against constitu

tional challenge Congress’ choice of the MBE plan “ to

ensure that (minority firms] were not denied equal op

portunity to participate in federal grants to state and

local governments . . . .” Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S.

448,478 (1980) (plurality).

Following the national lead, the Richmond City Coun

cil undertook an examination of the exclusion of minori

ties from participation in its own public contracting.

Council members had been concerned about minority par

ticipation in public contracting for some time. Votes on

a remedial set-aside at two meetings were postponed al

lowing further research apd analysis. J.A. 25-27.

During the postponements, council members, city ad

ministrators and the city attorney worked on the matter

3 Minority Business Utilization Plan, § 27.10-20, art. VIII-A ,

Richmond, Va., Ordinance 83.69-59 (April 11, 1983) (hereinafter

“ordinance” or "plan” ). Reproduced in Supplemental Appendices to

the Jurisdictional Statement. J.S. Supp. App. 233-58.

3

over “ a number of sessions.” J.A. 26-27. Their work in

cluded review of city construction contracts for the pre

vious five-year period and analysis of Fullilove and other

decisions passing on the legality of set-aside programs of

various configurations. J.A. 14-16, 24-27, 43. On A pril.

11, 1983, after hearing and public debate, the Council

adopted the Minority Business Utilization Plan.4 *

The City Council’s purpose in enacting the ordinance

was explicitly “ remedial . . . for the purpose or [sicl

promoting wider participation by minority business en

terprises in the construction of public projects, either as

general contractors or subcontractors.” 6 Councilman

Henry Marsh, a sponsor of the ordinance, stated, in urg

ing adoption of the set-aside plan, that the Richmond

construction industry was characterized by racial dis

crimination and “ exclusion on the basis of race” and that

the need for remedial action was “ not open to question.”

J.A. *2U.fl These views were echoed by the City Manager,

Manuel Deese. J.A. 42. Statistics presented to the Coun

4 Richmond was not alone in this approach. Since Fullilove, at

least 32 states and 160 local governments have adopted minority

set-aside requirements as part of their public contracting programs.

See Motion for Leave To File Brief of the National League of Cities,

et al., in Richmond v. Croson Co., No. 87-998, dated January 16,

1988, at p. 2.

6 Quoting the text of the ordinance as reproduced in an appendix

to the opinion of the District Court. J.S. Supp. App. 248.

fl In formulating and supporting the plan, Mr. Marsh drew on 22

years of experience in Richmond as a practicing attorney, Mayor

and member of the City Council. He had accumulated detailed

knowledge of the extent and effects of racial discrimination by pri

vate and public entities in Richmond as lead counsel for plaintiffs

in numerous lawsuits, including: Patterson v. American Tobacco

Co., 634 F.2d 744 (4th Cir. 1980), vacated, 456 U.S. 63 (1982)

(employment); Carson V. American Brands, Inc., 606 F.2d 420 (4th

Cir. 1979), rev’d, 450 U.S. 79 (1981) (employment); Quarles v. Philip

Morris, Inc., 279 F.Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968) (employment);

Evans v. Laurel Links, Inc., 261 F.Supp. 474 (E.D. Va. 1966)

(public facilities) ; Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, Virginia,

345 F.2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965), vacated on procedural grounds, 382

U.S. 103 (1965) (education).

4

cil showed that, from 1978 to 1983, when Richmond had

a minority population of 50%, two-thirds of 1% of the

$124 million of public construction contracts let had been

awarded to minorities. J.A. 12, 18, 41, 43.

Seven persons testified before the City Council on the

set-aside plan, including representatives of various asso

ciations of contractors opposing the proposal. J.A. 17-40.

None of those witnesses disputed either the fact of past

racial discrimination in the Richmond construction indus

try or its continuing effects. Nor did any witnesses dis

pute the remedial purpose of the set-aside plan. Rather,

these witnesses expressed concern over the lack of local

minority subcontractors, the possibility that sham minor

ity businesses would be awarded subcontracts, the poten

tial that the plan would lead to increased construction

costs, and the plan’s possible anti-competitive effects.

J.A. 20, 28, 31-36, 38-39.

Aware that this Court had approved a set-aside plan,

the authors of the Richmond plan carefully modeled it

after the federal one approved in Fullilove. J.A. 14-16,

24-27. The Council included a waiver and limited the

plan’s duration. J.A. 12, 14-15. The city attorney ex

plained:

“ The reason for that and the suggestion that a date

be put in, was that the federal cases that approved

this sort of set-up have said that it’s remedial legis

lation, and the purpose is to remedy past discrimi

nation. And hopefully, in some period of time, this

program will cause that to happen. Five years was

deemed to be a period of time with which that would

happen in all likelihood. It can be judged at that

time and either continued— it may expire before

that. It’s an ordinance that can be amended by

Council at any time. That was deemed to be a fair

date to evaluate the effects of the program rather

than leave it open-ended.” J.A. 14-15.

The Council considered the efficacy of the set-aside as

a remedy for the present effects of past discrimination.

An ordinance prohibiting race discrimination in the

5

award of city contracts had been on the books since

1975,7 yet the facts showed that minorities had nonethe

less been essentially excluded from public contracts from

1978 through 1983. In contrast, Council was advised that

the city’s community development block grant program

had utilized a set-aside requirement and achieved partici

pation by minorities exceeding the goals of that plan.

J.A. 41; see also J.A. 12-13, 16.

The Council was also aware that other cities, including

Oakland, Cleveland, Toledo, and Boston, had adopted

minority set-aside programs similar to the plan before

it. J.A. 16, 18-19. In addition, the Legislature of the

State of Virginia in 1982 had authorized public bodies to

establish programs to facilitate minority participation.8

The State also had established a Department of Minority

Public Enterprise.9

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case calls upon the Court to consider once again

the vexing issue of race-conscious remedies for the pres

ent effects of discrimination.10 These remedies have been

considered necessary to avoid perpetuating the effects of

past discrimination.11 Yet, the Court has recognized that

I Human Rights, Richmond, Va. Code § 17.2 (1975), attached

hereto as Appendix No. 2.

8 Virginia Public Procurement Act, § 11-48, Va. Code Ann. § 11.48

(1984).

* Id.

10 See, e.g., United States V. Paradise, 107 S.Ct. 1053 (1987);

Johnson v. Transp. Agency, Santa Clara Cty., Cal., 107 S.Ct. 1442

(1987); Local Number 93 v. City of Cleveland, 478 U.S. 501, 106

S.Ct. 3063 (1986); Local 28 of Sheet Metal Workers v. E.E.O.C.,

478 U.S. 421, 106 S.Ct. 3019 (1986); Wygant v. Jackson Board of

Education, 476 U.S. 267 (1986); Fullilove, supra; Steelworkers v.

Weber, 443 U.S. 193 (1979); University of California Regents v.

Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978).

II E.g., Wygant, 476 U.S. at 280-82 (plurality).

such remedies, focusing as they do on race, are them

selves problematic.1*

Perhaps because of the clash of these competing values,

the affirmative action cases that have come before the

Court have generally been resolved by combinations of

concurring opinions applying differing constitutional

tests. Although the requirements of these tests differ,

they reflect the common objective of achieving an appro

priate balance between substantial but competing rights.

Three types of such requirements are significant to the

resolution of this case: (1) limitations on the kinds of

discrimination a government may take affirmative action

to remedy, (2) requirements for supporting evidence that

the requisite discriminatory effects exist, and (3) require

ments that the remedy be “ narrowly tailored” to achieve

its purpose.

The uncertainty created by the absence of a single ap

proach in affirmative action cases was minimized in Fulli-

love, where six members of the Court approved the chal

lenged minority set-aside. While the concurring Justices

employed differing requirements, each opinion exhibited a

sensitivity to the particular context and avoided cate

gorical rules that would skew the balance of important

interests involved.

The remedial program challenged here, like numerous

similar state and local programs, was adopted, and ap

proved by the District Court, in compliance with the most

restrictive standard articulated by the Justices concurring

in Fullilove, the strict scrutiny applied by Justice Powell.

We show below that the Fourth Circuit reversed the

District Court on the basis-of principles derived from the

plurality opinion in Wygant v. Jackson Board of Educa

tion, 476 U.S. 267 (1986). Wygant, however, dealt with

governmental action dissimilar in purpose, operation and 12

6

12 E g-, United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144

172-75 (1977) (Brennan, J., concurring in part).

i

impact on non-minorities. The Fourth Circuit opinion

effectively abandons the balance struck in Fullilove and

should be reversed.

1. The Court of Appeals held that the City could

adopt a set-aside plan only to remedy its own past dis

crimination. This categorical limitation, not imposed in

Fullilove, adds no significant protection against abuse

yet would prohibit a uniquely effective remedy for iden

tified discrimination in the City’s construction industry.

This Court should reject it.' In any event, the City of

Richmond should.be permitted to adopt the plan to avoid

perpetuating the effects of that discrimination in its pub

lic contracting.

2. The Court of Appeals’ restrictive review of the evi

dence supporting Richmond’s plan disregarded this

Court’s precedents and usurped the fact-finding function

of the District Court. The District Court properly found

that the evidence supported Richmond’s action. If this

Court should change the applicable law and then conclude

that the District Court findings are inadequate, the case

should be remanded for further fact-finding by the Dis

trict Court.

3. The Court of Appeals employed an analysis incon

sistent with this Court’s precedents in holding that Rich

mond’s plan was not “ narrowly tailored.” Richmond’s

plan meets the tailoring requirements identified in this

Court’s cases.

The limits imposed by the Fourth Circuit have no sound

analytical foundation, contradict the persuasive and au

thoritative holding joined by six Justices in Fullilove,

and would upset the structure of remedial action by state

and local governments that has been erected on the foun

dation of Fullilove over almost a decade.

8

ARGUMENT

I. THE CONSTITUTION DOES NOT FORBID STATE

AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS FROM TAKING

RACE-CONSCIOUS ACTION TO CURE DISCRIMI

NATION AND ITS EFFECTS IN INDUSTRIES

WITH WHICH TH EY DO BUSINESS.

The Court of Appeals held Richmond’s set-aside plan

unconstitutional because the Council lacked “ a firm basis

for believing that such action was required based on prior

discrimination by the locality itself.” 822 F.2d at 1360.

That Court believed that the plurality in Wygant required

“ prior discrimination by the government unit involved”

before an affirmative action plan could be upheld. Id. at

1358, quoting 476 U.S. at 274 (plurality) (emphasis

added by Fourth Circuit). But Wygant imposed no such

requirement. Furthermore, if such a requirement were

appropriate, it is satisfied when state and local govern

ments award contracts to a construction industry they

know is characterized by discrimination.

A. State and Local Governments, Like Congress, May

Constitutionally Undertake Affirmative Action to

Cure the Effects of Past Discrimination Whether or

Not They Have Participated in Such Discrimination.

This Court has recognized that both Congress and

state governments have a substantial interest in remedy

ing the continuing effects of discrimination.13 14 * The Court,

13 E.g., Bakke, 438 U.S. at 307 (Powell, J.) ("The State certainly

has a legitimate and substantial interest in ameliorating, or elimi

nating where feasible, the disabling effects of identified discrimina

tion” ) ; id. at 3G9 (Brennan, White, Marshall, Blackmun, JJ.) ("a

state government may adopt race-conscious programs if the purpose

of such programs is to remove the disparate racial impact its

actions might otherwise have and if there is reason to believe that

the disparate impact is itself the product of past discrimination,

whether its own or that of society at large” ) ; Fullilove, 448 U.S. at

473 (plurality) (objective of ensuring that grantees electing to

participate in Federal program “would not employ procurement

practices that Congress had decided might result in perpetuation

of the effects of prior discrimination which had impaired or fore

y

however, has not reached agreement on the kinds of dis

crimination that justify use of race-conscious remedies.

Among the Justices approving such remedies, Justice

Powell has applied the most restrictive test. In his opin

ions in Bakke and Fullilove, Justice Powell wrote that

race-conscious remedies that aid some persons “ at the

expense of other innocent individuals” can be justified

only to cure the effects of “ identified discrimination” as

opposed to “ ‘societal discrimination,’ an amorphous con

cept of injury that may be ageless in its reach into the

past” ; and that such remedies must be based on “ judi

cial, legislative, or administrative findings of constitu

tional or statutory violations.” University of California

Regents v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 307 (1978); see Fulli

love, 448 U.S. at 497-98 (Powell, J., concurring) .'4

Notably absent from Justice Powell’s formulation was

any requirement that the “ identified discrimination”

found by the authoritative body be attributable to the

governmental unit adopting the remedy. Indeed, in Fulli

love, Justice Powell found his “ strict scrutiny” require

ments satisfied by congressional findings of actions by

private parties and governmental units other than Con

gress— actions that would, “ depending upon the identity

of the discriminating party, violate Title VI of the Civil

closed access by minority businesses to public contracting oppor

tunities” is within congressional power); id. at 497 (Powell, J.)

(citing Bakke, 438 U.S. at 3 0 7 ); Paradise, 107 S.Ct. at 10G4

(plurality) ( “ It is now well established that government bodies,

including courts, may constitutionally employ racial classifications

essential to remedy unlawful treatment of racial or ethnic groups

subject to discrimination, [citations omitted].” ).

14 Justices Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun and Chief

Justice Burger all recognized that race-conscious remedies require

some heightened scrutiny. Bakke, 438 U.S. at 358-62 (Brennan,

White, Marshall, Blackmun, J J .) ; Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 480 (Burger,

C. J .) ; id. at 519 (Marshall, J .). These Justices took the position

in those opinions, however, that the concerns requiring heightened

scrutiny could be adequately taken into account without the special

limitations imposed by Justice Powell.

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d et seq., or 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981, or the Fourteenth Amendment.” 448 U.S. at 506.

Justice Stewart complained in dissent that “ there is no

evidence that Congress has in the past engaged in racial

discrimination in its disbursement of federal contracting

funds.” Id. at 528.

In Wygant, Justice Powell applied his test to a collec

tive bargaining agreement between a school board and a

teachers’ union that required, in the event of layoffs, that

more senior non-minority employees be laid off before

minority employees. The purpose of this provision was

to preserve the attainments of an affirmative action hir

ing program. The lower courts, effectively by-passing the

issue whether the school board had itself discriminated,

upheld the lay-off provision on the basis of a need for

minority “ role-models” on the faculty to remedy the ef

fects of “ societal discrimination.” 476 U.S. at 274. The

number of desired role-models was keyed to the percent

age of minority students. Id. In rejecting the “ role-model”

justification, Justice Powell stated:

“ This Court never has held that societal discrimi

nation alone is sufficient to justify a racial classifi

cation. Rather, the Court has insisted upon some

showing of prior discrimination by the governmental

unit involved before allowing limited use of racial

classifications in order to remedy such discrimina

tion.” Id.

The Fourth Circuit interpreted this language to add

to the standard announced by Justice Powell in Balcke

and applied in Fullilove a requirement that the “ iden

tified discrimination” be discrimination by the govern

mental unit undertaking the affirmative action. 822 F.2d

at 1358. But neither Justice Powell, nor Justice O’Connor,

who stated the new requirement less ambiguously,15

15 Wygant, 476 U.S. at 288 (defining “societal discrimination” as

discrimination not traceable to [the governmental unit’s] own

actions” ).

acknowledged any intention to change the standard or

made any attempt to distinguish Fullilove or to articu

late what useful purpose was served by the additional

limitation.

We believe the most likely explanation for the language

in Wygant relied on by the Court of Appeals lies in the

particular facts of that case. Discrimination by the school

board itself was the most obvious, if not the only, “ iden

tifiable” discrimination in the materials before the Court.

The Court simply did not have before it the situation that

was presented in Fullilove and is presented by this case—

identifiable discrimination by a party other than the gov

ernmental unit adopting the remedy.10 The requirement

of findings of “ identified discrimination,” without the

further limitation to discrimination by the governmental

unit undertaking the plan, adequately satisfies Justice

Powell’s concern that the “ role model theory” and com

parison of the percentages of minority faculty and stu

dents were insufficient predicates for the race-conscious

action.11

The language suggesting this new aspect of Justice

Powell’s test was neither adopted by a majority of the

Court in Wygant, nor necessary to the result under any

of the opinions in that case.* 17 18 * * Nevertheless, as the opin

18 Justice O’Connor’s discussion of Wygant in Johnson, 107 S.Ct.

at 1462, contrasts “ societal discrimination” with “ past and present

discrimination by the employer" (emphasis added). Since prime

contracting firms are employers, Justice O’Connor’s test in Johnson

could be satisfied under the facts here without discrimination by

the City.

17 According to Justice Powell, the "role model theory” has "no

logical stopping point” and would allow the Board to discriminate

“ long past the point required by any legitimate remedial purposes.”

He also believed it could be used to “escape the obligation to rem

edy” relevant statistical imbalances indicative of discrimination.

476 U.S. at 275-76.

18 Because of the status of the record and the proceedings

below, all three opinions supporting the result rested not on the

absence of a finding that the School Board had itself discriminated,

but on the inappropriate nature of the remedy. 476 U.S. at 278

12

ion below illustrates, the Wygant dicta has had an im

pact on the courts of appeal.1®

Neither the Fourth Circuit nor any other court over

turning a set-aside plan on the basis of the Wygant dicta

has explained how limiting States and localities to curing

their own identified discrimination, as opposed to identi

fied discrimination by others, would improve the balance

between the competing interests involved. This Court

should now reject that restriction.

The Fourth Circuit suggests that the limitation serves

some purpose in preserving the “ line between remedial

measures and political transfers,” 822 F.2d at 1360, but

does not explain what, if any, additional protection the

new limitation adds to the requirement that the discrimi

nation to be cured be “ identified.” The Court s justifica

tion ignores identified discrimination by others and as

sumes that the only alternative to discrimination by the

locality itself is unidentified “ societal discrimination.”

The Fourth Circuit’s attempt to distinguish Fullilove

on the basis of “ the special competence of Congress,” 822

F.2d at 1360, turns the structure of the Constitution on

its head. While Congress must find an affirmative basis

for its authority in the Constitution,20 the Constitution

leaves States free to exercise all powers subject to ex

pressed limitations. Although Congress needed special

authorization to pass legislation enforcing the equal pro

tection guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment, the

(plurality); id. at 293-94 (O’Connor, J., concurring in part and in

judgm ent); id. at 294-95 (White, J., concurring in judgment).

i# See, e.g., Michigan Road Bkilders A ss’n, Inc. v. Milliken, 834

F.2d 583, 589-90 (6th Cir. 1987); Assoc. Gen. Contr. of Cal. V. City

& County of S.F., 813 F.2d 922, 929-30 (9th Cir. 1987).

20 This special need to explain the basis of federal authority

accounted for extended discussion in Fullilove. 448 U.S. 473-80

(plurality); id. at 499-502 (Powell, J.).

States needed no such special authority. Bnlcke, 438 U.S.

at 368 & n.44 (Brennan, White, Marshall, Blackmun,

JJ.).21

The District Court here held that Richmond’s action

was authorized under state law, J.S. Supp. App. 141-55,

and the Fourth Circuit affirmed, 779 F.2d at 181, 184-186

(1985). Although the Fourth Circuit’s opinion was va

cated by this Court and remanded in light of Wygant,

the fact that the Court of Appeals reached the federal

constitutional issue in its remand opinion indicates that

its position on the state law issues has not changed.22

In sum, the Constitution permits Richmond to exercise

the power delegated to it by the State to enact a minority

set-aside plan as a remedy for past discrimination by

others without a threshold showing of its own participa

tion in that discrimination.

B. State and Local Governments Participate in Dis

crimination When They Award Contracts to a Con

struction Industry Characterized by Discrimination.

Assuming arguendo that the Fourteenth Amendment

limits a city’s authority to remedying discrimination in

which the city itself has participated, the Richmond plan

should nevertheless be approved. A local government be

comes a participant in discrimination when it awards

contracts to companies in an industry characterized by

discrimination.

Richmond has a special interest in curing, at least in

the context of public contracting, the effects of past dis

21 See Schnapper, Affirmative Action and the Legislative History

of the Fourteenth Amendment, 71 Va. L. Rev. 753 (1985).

22 See Schmidt V. Oakland Unified School Dist., 457 U.S. 594

(1982), vacating and reversing 662 F.2d 550 (9th Cir. 1981) (lower

court improperly failed to consider authority of locality under state

law prior to reaching federal constitutional question).

14

crimination by those in the construction industry. In the

absence of such curative action, Richmond s facially

neutral” awards of public contracts inevitably perpetuate

the effects of past discrimination. This Court in Fulli-

love recognized the importance of eliminating such state

involvement. Chief Justice Burger stated: “ [Congres

sional authority extends beyond the prohibition of pur

poseful discrimination to encompass state action that has

discriminatory impact perpetuating the. effects of past

discrimination. South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S.

301 (1966); cf. City of Rome [v. United States, 446 U.S.

156, 176-77 (1980)].” 448 U.S. at 477 (plurality). He

emphasized that “ traditional procurement practices, when

applied to minority businesses, could perpetuate the ef

fects of prior discrimination,” and approved a minority

set-aside program “ to ensure that those businesses were

not denied equal opportunity to participate in federal

grants to state and local governments, which is one as

pect of the equal protection of the laws.” Id. at 478.

Subsequent cases have recognized the States’ interest

in ensuring public access to commercial opportunities—

including those in the private sector— free from the

taint of discrimination. Roberts v. United States Jaycees,

468 U.S. 609 (1984) ; Board of Directors of Rotary In

ternational v. Rotary Club of Duarte, 107 S.Ct. 1940

(1987). States have an even greater interest in assur

ing nondiscriminatory access to commercial opportunities

they themselves provide.

A governmental entity that participates in “ business

as usual” by awarding public contracts with knowledge

of discrimination in the industry performing them vio

lates the Fourteenth Amendment. The entity under such

circumstances is a “ joint participant in a pattern of

racially discriminatory conduct. . . .” Ethridge v. Rhodes,

268 F. Supp. 83, 87 (S.D. Ohio 1967). There the court

granted an injunction against a state construction proj

ect because minorities “ will not be able to get jobs.” Id.

Although it was the union that refused to refer blacks,

the court rejected the state’s defense that there was no

state action:

“ [W]hen a state has become a joint participant in

a pattern of racially discriminatory conduct by plac

ing itself in a position of interdependence with pri

vate individuals acting in such a manner— that is,

the proposed contractors acting under contract with

unions that bar Negroes— this constitutes a type of

‘state action’ proscribed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Burton V. Wilmington Parking Authority,

[365 U.S. 715 (1961)]. Thus, . . . where a state

through its elected and appointed officials, under

takes to perform essential governmental functions—

herein, the construction of facilities for public edu

cation— with the aid of private persons, it cannot

avoid the responsibilities imposed on it by the Four

teenth Amendment by merely ignoring or failing to

perform them.” Id.

Other courts have accepted the “ state action” theory ar

ticulated in Ethridge. Nat. Black Police Ass’n, Inc. v.

Velde, 712 F.2d 569, 580-83 (D.C. Cir. 1983) (federal

agency had constitutional duty to terminate funds to local

agencies known to be engaging in discrimination) ; Percy

v. Brennan, 384 F. Supp. 800, 811-12, (S.D.N.Y. 1977)

(government acquiescence in racially discriminatory prac

tices by construction industry is a statutory and constitu

tional violation).

Limiting the power of States and localities to remedy

the effects of past discrimination to those situations

where the entity has itself discriminated does not meas

urably advance the goals of equal protection. This Court

should recognize that, at the very least, governments are

not barred from attempting to free their own public con

tract awards from the taint of discrimination, whether

their own or that of the industry that bids on the

contracts.

16

II. THE FOURTH CIRCUIT IMPROPERLY HELD

TH AT RICHMOND HAD NO FIRM BASIS FOR

BELIEVING REMEDIAL ACTION W AS REQUIRED.

We have considered the kinds of discrimination that

can justify a set-aside plan. We now examine the sup

port for a conclusion that discrimination of the requisite

nature existed here.

The District Judge determined after review of the ap

plicable law and the evidence before him that

“ the evidence before the City Council when it en

acted the ordinance supports the conclusion that par

ticipation of minority businesses in the Richmond

area construction industry in general, and the City’s

construction contracting in particular continues to

be adversely affected by past discrimination.” J.S.

Supp. App. 163-64.

Although the District Court unambiguously found dis

crimination in the construction industry, id. at 163, its

findings are less explicit with respect to. intentional dis

crimination by the City itself (aside from the City’s

perpetuation of discrimination by others through its pub

lic contracting). At the time of its decision, Wygant had

not been decided and more precision on this issue was

unnecessary.

The Fourth Circuit on remand held the plan uncon

stitutional because the record failed to satisfy the re

quirement, derived from the Wygant dicta, for evidence

that the plan was adopted to cure the City’s own dis

crimination. Rather than remanding to allow the District

Court to consider the case under this new standard, the

majority resolved the factual issues under that standard

itself, without briefing by the parties. 822 F.2d at 1358-

60. In contrast, the dissent concluded that “ the Richmond

Council had a firm basis for believing it had engaged in

past discrimination in awarding public contracts.” Id.

at 1364.

This Court’s determination of the kinds of discrimi

nation that can justify a set-aside plan will frame the

relevant evidentiary issues. If this Court holds that

Richmond was permitted to adopt a set-aside remedy to

avoid perpetuating through award of public contracts the

effects of past discrimination in the construction indus

try, then the District Court’s finding quoted above should

be adequate to support that purpose. That finding should

be affirmed unless clearly erroneous. Alternatively, if this

Court should require that the City itself discriminated,

the Court would have to determine whether the District

Court made an adequate finding on that issue. If so, that

finding should be upheld unless clearly erroneous. If not,

the case should be remanded to the District Court for

reconsideration in light of the standard announced by the

Court.

Regardless of how this Court resolves the issues in

Part I, the Fourth Circuit’s treatment of the evidentiary

issues was erroneous. The Court of Appeals violated three

principles derived from this Court’s prior cases that

should govern consideration of the evidentiary issues in

this case: (1) to preserve the incentive for voluntary

remedial action by a party in jeopardy of suits from op

posing sides, contemporaneous self-incriminatory findings

will not be required;23 (2) legislative action does not re

quire record support of the formality necessary to sustain

judicial or administrative action;24 * and (3) the district

23 The adverse impact on incentives for voluntary action “cannot

. . . be justified by reference to the incremental value a contem

poraneous findings requirement would have as an evidentiary safe

guard” . Wygant, 476 U.S. at 289-91 (O’Connor, J., concurring).

See Bakke, 438 U.S. at 364 (Brennan, White, Marshall, Blackmun,

J J .) ; Johnson, 107 S.Ct. at 1450-51. Accordingly, the Court has

required at most a “ firm basis for concluding that remedial action

was appropriate.” Wygant, 476 U.S. at 292-93 (O ’Connor, J .) ; id.

at 277 (plurality).

24 Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 478 (plurality): id. at 502 (Powell, J.).

Rather than “confinfing] its vision to the facts and evidence ad

duced by particular parties,” a legislative body has the “broader

mission to investigate and consider all facts and opinions that may

be relevant to the resolution of an issue." Id. at 502-03. The “ in

formation . . . expertise [and] experience” of legislators are an

18

court plays the dominant role in finding facts.25

A. The District Court’s Finding that the City Had

Adequate Support for Believing that Its Public

Contracting Awards Were Perpetuating Effects of

Discrimination Should Be Sustained.

If this Court holds that the Constitution permits Rich

mond to take affirmative action either to cure the effects

of discrimination in the construction industry or to pre

vent the perpetuation of those effects through award by

the City of public contracts, it will then have before it a

clear finding by the District Court, supra, p. 16, that the

City Council had sufficient support for either purpose.

That finding is not “ clearly erroneous” ; indeed, it is

clearly correct.

1. The Council had before it a striking statistical dis

parity: from 1978 to 1983, less than 1% of city con

struction contracts, a figure approaching “ the inexorable

“appropriate source.” Id. at 503. See Ohio Contractors Ass'n v.

Keip, 713 F.2d 167, 171 (6th Cir. 1983) (legislators deemed to be

aware of prior judicial findings, executive investigations and prior

legislative work regarding discrimination); Southwest Washing

ton Chap., Nat’l Elec. Contr. Assn. v. Pierce Cnty., 667 P.2d 1092,

1100 and n.2 (Wash. 1983) (recognizing that the work of local

legislative bodies occurs at meetings and conferences but that local

bodies “cannot be expected to undertake the expense of detailed

recordkeeping comparable to Congress” ).

25 A district court’s determination whether or not discrimination

occurred is a finding of fact subject to F. R. Civ. P. 52(a), and

must be affirmed unless “clearly erroneous” or based on an incor

rect legal standard. Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273, 289

(1982). When the district court either fails to make necessary

findings or makes findings that are infirm because of an error of

law, a remand is “proper unless the record permits only one resolu

tion of the factual issue.” Id. at 291-92. A determination whether

a legislative body had a sufficient basis for believing discrimination

justifying affirmative action had occurred differs from a court’s

determination that discrimination occurred. But the district court’s

role is essentially the same— weighing the evidence according to

appropriate legal standards— and the same institutional considera

tions apply. See Anderson V. Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564, 574-75

(1985).

zero,” 28 were awarded to minority contractors in a city

with a 50% minority population. The Fourth Circuit re

jected this statistical evidence, characterizing the dispar

ity as “ spurious” : “ [t]he appropriate comparison is be

tween the number of minority contracts and the number

of minority contractors . . . .” 822 F.2d at 1359 (em

phasis in original).

Wygant, upon which the Fourth Circuit relied heavily,

is readily distinguishable. There, this Court rejected the

statistical relationship between minority teachers and

minority students as a basis for a plan protecting minor

ities from lay-offs. As this Court recognized, that statis

tical relationship was not relevant to whether there had

been discrimination against minority teachers. 476 U.S.

at 274-76.* 27

By contrast, a comparison of the percentage of public

contracts awarded to minorities with the percentage of

minorities in the general population is relevant to a

determination whether discrimination has occurred. Com

parisons to groups narrower than the general population

may as a general rule be preferable as evidence of dis

crimination. Nevertheless, where racial discrimination at

the “ entry level” has thwarted the development of minor

ity businesses or prevented minorities from acquiring

skills, this Court has approved the use of general popula

tion statistics as a proxy for the number of minorities

that would be present in the more narrowly defined pop

ulation but for the effects of present and past discrimi

nation. See Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324,

e8 Johnson, 107 S.Ct. at 1465 (O’Connor, J .), citing Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324, 342, n.23 (1977).

27 Papers before this Court in Wygant indicated that in 1972,

the percentage of minority students, 16% , was dramatically higher

than the percentage of minorities in the general community popula

tion, about 4% . Minority teachers in 1972 represented 8% of the

faculty and thus exceeded the minority representation in the com

munity. Brief of amicus Anti-Defamation League in Wygant, pp

i, 12-13.

20

339-40 & n. 20 (1977); Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S.

193, 198-99 (1979); id. at 215 (Blackmun, J., concur

ring) • Johnson v. Transp. Agency, Santa Clara Cty., Cal,

107 S. Ct. 1442, 1450 (1987), id. at 1462-1463 (O’Connor,

J., concurring) ; United States v. Paradise, 107 S. Ct.

1053, 1065 & n. 19 (plurality). Thus, in Fullilove itself,

this Court accepted Congress’ comparison of the percent

age of contracts awarded minority contractors, 1%, with

the percentage of minorities in the general population, 15-

18%, as “ evidence of a long history of marked disparity

in the percentage of public contracts awarded to minority

business enterprises.” 448 U.S. at 478 (plurality).

This Court has accordingly avoided the “gross anom

aly” pointed out by the dissent below— “ a proof scheme

requiring a comparison of the percentage of contracts

awarded with this small qualified pool of minority con

tractors would ensure the continuation of a systematic

fait accompli, perpetuating a qualified minority contrac

tor pool [that reflects discriminatory barriers to entry 1.”

822 F.2d at 1365 & n .ll. See Johnson, 107 S.Ct. at 1462

(O’Connor, J .).28

Similar concerns have led the Office of Federal Con

tracts Compliance Programs ( “ OFCCP” ) of the U.S. De

partment of Labor, the agency charged with assuring

non-discrimination by federal contractors, to use the per

centage of minorities in the general population as the

basis for setting affirmative action employment goals to

be met by federal construction contractors. 45 Fed. Reg.

65976 et seq. (Oct. 3, 1980). Various contractors ob

28 Other communities have used comparisons with the minority

population in assessing the need for remedial set-asides. See, e.g.,

South Fla. Chap. v. Metropolitan Dade County, Fla., 723 F.2d 846,

855 (11th Cir. 1984) (citing disparity between percentage of black

county contractors (1 % ) and the county’s general black population

( 1 7 % ) ) ; Schmidt v. Oakland Unified School Dist., 662 F.2d at 559

(“statistical disparity between the sizeable minority population of

the community and the meager extent” of minority participation in

public contracts).

jected to establishment of goals on an industry-wide

basis reflecting general population statistics, and made

arguments similar to those accepted by the Fourth

Circuit:

“ Contractors contended that the minority goals

should be by individual trade/craft rather than a

single goal for all crafts because to do otherwise

ignores the unavailability of minority construction

workers, both skilled and unskilled, and makes it

virtually impossible for contractors to meet the goal.”

Id. at 65983.

The OFCCP rejected this argument, relying on Weber:

“ the single goal concept is predicated upon the prop

osition that had it not been for the long-standing

exclusion of minorities from the skilled construction

crafts, minorities would be represented in those

crafts at least to the extent of their representation

in the total labor force in a given geographical area.

(See United States Workers of America v. Weber,

443 U.S. 193).” Id.

2. The District Court, as did the Council, weighed as

well other evidence indicating discrimination in the con

struction industry. The Court of Appeals characterized

that other evidence as “ meager,” consisting of “ some con-

clusory and highly general statements.” 822 F.2d at

1358. This characterization exemplifies the kind of

overly-technical factfinding requirements condemned by

this Court in Fullilove. 448 U.S. at 478-80 (plurality);

id. at 502-03 (Powell, J .).29

As described in detail in the Statement, supra, pp. 2-5,

the Council’s framing and adoption of the set-aside plan

a® See also Wygant, 476 U.S. at 289-91 (O’Connor, J). It is re

vealing to compare Judge Wilkinson’s majority opinion on remand

with his dissent, which is more explicit about requiring “detailed

factual findings.” E.g., 779 F.2d at 204. While the later opinion

acknowledges the principles noted at pp. 17-18, supra, 822 F.2d at

1359, its approach to the record belies its words.

22

were informed by the hearing proceedings30 and by the

studies of Council members and city administrators and

their wealth of experience with the extent and effects of

prior segregation and discrimination in Richmond. This

experience and evidence either were not considered or

were rejected by the Fourth Circuit as “nearly weight

less.” 822 F.2d at 1359.

In evaluating the Council’s action, the District Court

took judicial notice of the congressional findings of dis

crimination in the construction industry detailed by this

court in Fullilove. J.S. Supp. App. 165-166.31

3. In sum, there is more than adequate support for

the District Court’s finding that Richmond had suf

ficient evidence to believe its action was necessary to cure

the effects of discrimination in the construction industry,

and, in particular, the perpetuation of those effects in the

awarding of public contracts.

B. The Council Had a Reasonable Basis To Believe

that the City Itself Had Discriminated.

If this Court should hold that in order to justify the

set-aside plan, Richmond must demonstrate that there

was a reasonable basis for believing that the City itself

had discriminated, the existence of the requisite evidence

and finding is not so clear. Two factors explain the am

30 Opponents of the ordinance had reviewed the proposed setaside

and prepared for the Council debate in advance. Two construction

industry organizations had retained counsel from a prominent

Richmond law firm to present their case to the Council. J.A. 19.

31 Pervasive discrimination and racial exclusion in the construc

tion industry have been so well documented by courts that this

Court has found them to be a proper subject for judicial notice.

Weber, 443 U.S. at 198 & n .l (“Judicial findings of exclusion from

crafts on racial grounds are so numerous as to make such exclusion

a proper subject for judicial notice.” ). See also Grant V. Bethlehem

Steel Corp., 635 F.2d 1007 (2d Cir. 1980) ; Local Union No. 35 of

IB E W V. Hartford, 625 F.2d 416 (2d Cir. 1980); Denton v. Boiler

makers, 650 F.Supp. 1151 (D. Mass. 1986).

23

biguity of the existing record and the District Court’s

findings on the issue of the City’s own discrimination:

members of the Council were reluctant to incriminate

themselves or the City.32 and the precedents available to

the Council and the District Court did not require any

finding that the City itself had discriminated in order to

justify such a program. See, supra, pp. 8-15.

Nevertheless, the District Court’s finding that “ the

City’s construction contracting in particular continues to

be adversely affected by past discrimination,” J.S. Supp.

App. 164, could be read to mean that the City itself had

discriminated. The dissent below so concluded.31 To find

that discrimination by the City itself played no role in

the past exclusion of minority contractors from public

32 One Council member expressed fear that adoption of a remedial

program would expose the City to liability for past discrimination

(J.A. 1 5 ) :

“ CITY A TTO R N EY: No, I don’t feel that we’re exposing

ourselves to liability, but the Supreme Court, when it approved

the ten percent minority set-aside, specifically said that the

justification was that it was remedial. W e’ve reviewed the

statistics of the construction contracts, and it certainly justifies

that. We have tried to tailor this ordinance as closely to the

federal ordinance, which was— or federal statute, which was

upheld by the Supreme Court, as possible. And, yes, it is

remedial. I don’t think that’s exposing us to any liability for

prior acts.

"COUNCIL M EM BER: . . . Doesn’t the word remedial mean

to make special efforts at the moment and in the near future

to make up for prior deficiencies?

“CITY A T T O R N E Y : Yes. In the term remedial, we’re not

just implying that the City was intentionally discriminatory in

the past. What we’re saying is there are statistics about the

number of minorities that were awarded contracts in the past

which would justify the remedial aspects of the legislation.

W e’re not saying there was intentional discrimination in any

particular case. . . . And they allowed more use of broader

statistics than they do in a lot of cases. I’m not saying that

we have discriminated in any individual case in the past.”

33 "The conclusions that emerged from the Council’s debate con

cerned the City’s previous discrete discrimination in awarding con

tracts for public construction projects.” 822 F.2d at 1366.

24

contracts would require closing one’s eyes to the history

of Richmond’s pervasive purposeful discrimination that

was all too familiar to the Council members.* 34 *

Should the Court conclude that the District Court’s

findings cannot be read to support the City’s belief in

its own discrimination, the proper course would be to

remand to the District Court for appropriate findings un

der the new standard imposed by the Court. See Pull

man-Standard. v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273, 291-92 (1982).

III. THE RICHMOND PLAN IS NARROWLY TAILORED

TO ACHIEVE ITS REMEDIAL GOAL OF ENDING

RACIAL EXCLUSION IN PUBLIC CONTRACTING.

We now consider the third criterion for evaluating the

constitutionality of Richmond’s set-aside ordinance: the

requirement that the plan be “ narrowly tailored to the

achievement of [its] goal.” Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 480

(plurality). In his concurrence in Fullilove, Justice

Powell cautioned that this requirement does not restrict a

legislature to the “ least restrictive” alternative. Id. at

508. Rather, the legislature’s “ choice of a remedy should

be upheld . . . if the means selected are equitable and

reasonably necessary to the redress of identified dis

crimination.” Id. at 510. Justice Powell described the

measure of discretion accorded Congress “ to choose a

suitable remedy for the redress of racial discrimination”

as similar to judicial discretion in choice of remedies— a

balancing process left to the sound discretion of the trial

court. Id. at 508, citing Franks v. Boivman Transp. Co.,

424 U.S. 747, 794 (1976) (Powell, J. concurring in part

and dissenting in part). See also Paradise, 107 S.Ct. at

1073-74 (plurality).

This Court has generally considered the five factors,

originally identified by Justice Powell, in deciding

whether a remedy is properly tailored: “ (i) the efficacy

84 See City of Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358 (1975);

Bradley v. School Board, 462 F.2d 1058 (4th Cir. 1972); aff’d by

an equally divided Court, 412 U.S. 92 (1973) (per curiam).

of alternative remedies . . ., (ii) the planned duration

of the remedy . . (iii) “ the percentage chosen for the

set-aside . . (iv) “ the availability of waiver . . and

(v) “ the effect of the set aside upon innocent third par

ties.” Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 510-14. See Paradise, 107

S.Ct. at 1067; Johnson, supra. The Fourth Circuit mis

applied these factors in reaching its alternative holding

that Richmond’s program was not adequately tailored.

A. The City Council Considered Alternatives.

This Court in Fullilove indicated that Congress’ ex

perience with other unsuccessful remedies demonstrated

that it had adequately considered alternatives.

“ By the time Congress enacted [the set-aside] in

1977, it knew that other remedies had failed to

ameliorate the effects of racial discrimination in the

construction industry. Although the problem had

been addressed by antidiscrimination legislation, ex

ecutive action to remedy employment discrimination

in the construction industry, and federal aid to mi

nority businesses, the fact remained that minority

contractors were receiving less than 1% of federal

contracts.” 448 U.S. at 511 (Powell, J.).

Similarly, the Richmond Council had tried an anti-

discrimination provision. In place since 1975, this prohi

bition on discrimination in award of public contracts had

not affected the barriers to entry preventing minority

participation in public contracting. On the other hand,

the Council was advised that a set-aside used in the

community development block grant program had had

more favorable results. See pp. 4-5, supi'a. The record

shows that, based on their past experience, the council

members selected a remedy they believed held more prom

ise of success than other alternatives.88

88 Because the set-aside effectively requires non-minority con

tractors to work with MBEs, it is the only alternative which may

overcome “ lack of confidence in minority business ability or racial

26

B. The Set-Aside Program Is Limited in Duration.

The set-aside adopted by Richmond is a temporary

measure, expiring on June 30, 1988, five years after it

became effective. J.S. Supp. App. 247-48. The Fourth

Circuit treated the automatic expiration as something

less than automatic— “ [wlhether the Richmond plan will

be retired or renewed in 1988 is . . . nothing more than

speculation.” 822 F.2d at 1361.

The duration factor is used to guarantee that the

program in question is a temporary remedy to cure the

effects of past discrimination rather than a permanent

mechanism to maintain racial balance. In Johnson and

Weber, this Court approved affirmative action plans as

remedial and temporary in operation even though the

plans contained no specific termination dates. Johnson,

107 S.Ct. at 1456; Weber, 433 U.S. at 208-09. By con

trast, the Richmond plan is explicitly temporary. See p.

4, supra.

m

C. The Council Selected a Reasonable Figure for the

Set-Aside Percentage.

Richmond established a 30% set-aside goal based on a

50% general minority population. The Fourth Circuit

criticized the 30% goal as arbitrary. 822 F.2d at 1360.

This criticism is unfounded.36 *

In establishing the 30% goal, Richmond applied Jus

tice Powell’s approach in Fullilove to the local circum

stances. Justice Powell approved “ [t]he choice of a 10%

set-aside [fallingl roughly halfway between the present

percentage of minority contractors and the percentage of

prejudice and misconceptions.” Constructors Assoc, of Western Pa.

V. Kreps, 441 F. Supp. 936, 953 (W .D. Pa. 1977).

39 Judge Sprouse, dissenting, said that "judging the set-aside

percentage by referring to the small proportion of existing MBEs

in the economy would perpetuate rather than alleviate past dis

crimination.” 822 F.2d at 1367.

minority group members in the Nation.” 448 U.S. at

513-14. Although the specific number of minority con

tractors in Richmond is not contained in the record, the

City Council was informed by the representatives of the

construction industry who testified on the plan that there

were few. J.A. 27, 33-36, 40, 44. The 30% figure falls

roughly halfway between the minority participation rate,

below 1%, and the minority population of b0%.ai

Buttressing the reasonableness of the percentage chosen

by the Council is the related action of the OFCCP which

set employment goals for the construction industry sub

stantially equal to the minority population percentage.

See p. 21, supra.

D. The Richmond Plan Provides for an Adequate

Waiver.

In order to assure that its plan was flexible, Richmond

incorporated a waiver provision.38 A non-minority con

tractor may obtain a waiver of the 30% subcontracting

requirement on a showing that despite best efforts there

are no minority subcontractors available or willing to

participate. The District Court, applying Fullilove found

the waiver sufficient to protect against rigid application.

J.S. Supp. App. 175-93.

•t see Southwest Washington Chap. V. Pierce Cnty., supra, 667

P.2d at 1101 (approved MBE goal “slightly less than the minority

population in Pierce County” ) ; Schmidt v. Oakland Unified School

Dist., supra, 662 F.2d at 559 (approving 25% MBE goal where city

population was 34.5% minority).

38 The standard for waiver is as follows:

“ . . . it must be shown that every feasible attempt has been

made to comply, and it must be demonstrated that sufficient,

relevant, qualified Minority Business Enterprises (which can

perform subcontracts or furnish supplies specified in the con

tract bid) are unavailable or unwilling to participate in the

contract to enable meeting the 30% MBE goal.” J.S. Supp.

App. at 68.

28

The Fourth Circuit rejected the waiver because it is

limited to “ ‘exceptional circumstances/ ” and is a matter

of “ administrative discretion” and because the prime

contractor bears the “ burden of obtaining the waiver.”

822 F.2d at 1361. The Richmond “ waiver provisions were

purposely drawn to parallel those approved in Fullilove,”

822 F.2d at 1367 (Sprouse, J., dissenting), and the

waiver approved in Fullilove was also available only

“ under exceptional circumstances.” Compare J.S. Supp.

App. 67 with 448 U.S. at 494. In Fullilove, as here, the

waiver decision was an exercise of administrative dis

cretion. Id. at 468-72. Finally, in each case the entity re

sponsible for complying with the percentage set-aside

(i.e., the State or locality in Fullilove and the contractor

here) is the entity that may seek the waiver. J.S. Supp.

App. at 189. In sum, the Fullilove standard was followed

and the contractors are given “ the opportunity to demon

strate that their best efforts” will not achieve the “ target

for minority firm participation.” 448 U.S. at 488 (plu

rality).

E. The Burden on Non-Minorities Is Consistent with

Fundamental Fairness.

Inherent in the set-aside concept is the “ ffjailure of

non-minority firms to receive certain contracts . . ., an in

cidental consequence of the program.” Id. at 484 (plu

rality). This burden is to be assessed to determine

whether “ the effect of the set-aside is limited and so

widely dispersed that its use is consistent with funda

mental fairness.” Fidlilove, Id. at 515; Wygant? 476

U.S. at 282-83. The Fourth Circuit erroneously con

cluded that the Richmond set-aside “ imposes an overbroad

competitive burden on non-minority businesses.” 822 F.2d

at 1361.

The burden imposed by the Richmond set-aside is lim

ited in scope and duration. The set-aside applies only to

subcontracts and not to prime contracts. Since it applies

to all non-minority contractors, the burden is shared by

many. Those who share this limited burden inevitably

include many who benefitted from prior discrimination.

Because these contracts represent only a fraction of con

struction projects, the set-aside affects “ only one of sev

eral opportunities.” 3“ Wygant, 476 U.S. at 283.

Finally, this set-aside, unlike the lay-offs disapproved

in Wygant, does not disturb any “ firmly rooted expecta

tion.” Johnson, 107 S. Ct. at 1455.

In sum, review of the Richmond set-aside plan in light

of the five factors articulated by this Court compels the

conclusion that the ordinance was narrowly tailored to

achieve its remedial purpose.

39 Using census data, the City in its brief to this Court has

calculated that city projects accounted for only 10% of all con

struction contracts during 1978 to 1983. The set-aside thus affects

only three percent of local contracting opportunities. Because non-

minorities can participate as a 49% owner in an MBE or can form

a 51% -49% joint venture with an MBE and still receive a set-

aside, the opportunities affected are reduced even further.

30

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, we urge the Court to

reverse the decision below of the Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit and uphold the Richmond Minority

Business Utilization Plan as constitutional.

Conrad K. Harper

Stuart J. Land

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

W illiam L. Robinson

Judith A. W inston

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W .

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

A ntonia Hernandez

Richard E. Larson

Mexican-A merican

Legal Defense and

Educational Fund

634 South Spring Street

Los Angeles, California 90014

(213) 629-2512

Attorneys for

Respectfully submitted,

Stephen J. Pollak *

James R. Bird

Paula A. Sweeney

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

Grover Hankins

Joyce Knox

National A ssociation

for the A dvancement

of Colored People

4805 Good Hope Drive

Baltimore, Maryland 21215

(301) 243-9191

Judith L. Liciitman

Claudia W ithers

W omen ’s Legal

Defense Fund

2000 P Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 887-0364

Amici Curiae

* Counsel of Record

April 21, 1988

APPENDICES

APPENDIX NO. 1

Description of Amici Organizations

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

is a nonprofit organization established in 19G3 at the

request of the President of the United States to involve

leading members of the bar throughout the country in a

national effort to insure civil rights to all Americans.

Through its national office in Washington, D.C., and its

local Lawyers’ Committees such" as the Washington, D.C.

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, the

organization has over the past 25 years enlisted the serv

ices of thousands of members of the private bar in ad

dressing the legal problems of minorities and the poor in

voting, education, employment, housing, municipal serv

ices, the administration of justice, and law enforcement.

The Mexican-American Legal Defense and Educational

Fund is a national civil rights organization founded in

1967. Its principal objective is to secure, through litiga

tion and education, the civil rights of Hispanics in the

United States.

The NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund (“ NOW

LDEF” ) is a nonprofit civil rights organization that per

forms a broad range of legal and educational services

nationally in support of women’s efforts to eliminate sex-

based discrimination and secure equal rights. NOW

LDEF was established in 1970 by leaders of the National

Organization for Women. In seeking to eliminate bar

riers that deny women economic opportunities, NOW

LDEF has participated in numerous cases to secure full

enforcement of laws prohibiting employment discrimina

tion, including cases before this Court involving chal

lenges to the use of affirmative action remedies to achieve

equal employment opportunity.

The National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People is a New York nonprofit membership cor-

2a

poration founded in 1909. The principal objective of the

NAACP is to ensure the political, educational, social and

economic equality of minority group citizens and to

achieve equality of rights and eliminate race prejudice

among the citizens of the United States. The General

Counsel’s office represents the 1800 branches in litigation

involving voting, housing, school desegregation and em

ployment discrimination.

The Women’s Legal Defense Fund ( “ WLDF” ) is a

nonprofit, tax-exempt membership organization founded

in 1971 to provide legal assistance to women who have

been discriminated against on the basis of sex. The Fund

devotes a major portion of its resources to combatting

sex discrimination in employment, through litigation of

significant employment discrimination cases, operation of

an employment discrimination counselling program, pub

lic education, and advocacy before the EEOC and other

federal agencies charged with enforcement of equal op

portunity laws. In its pursuit of equality for both women