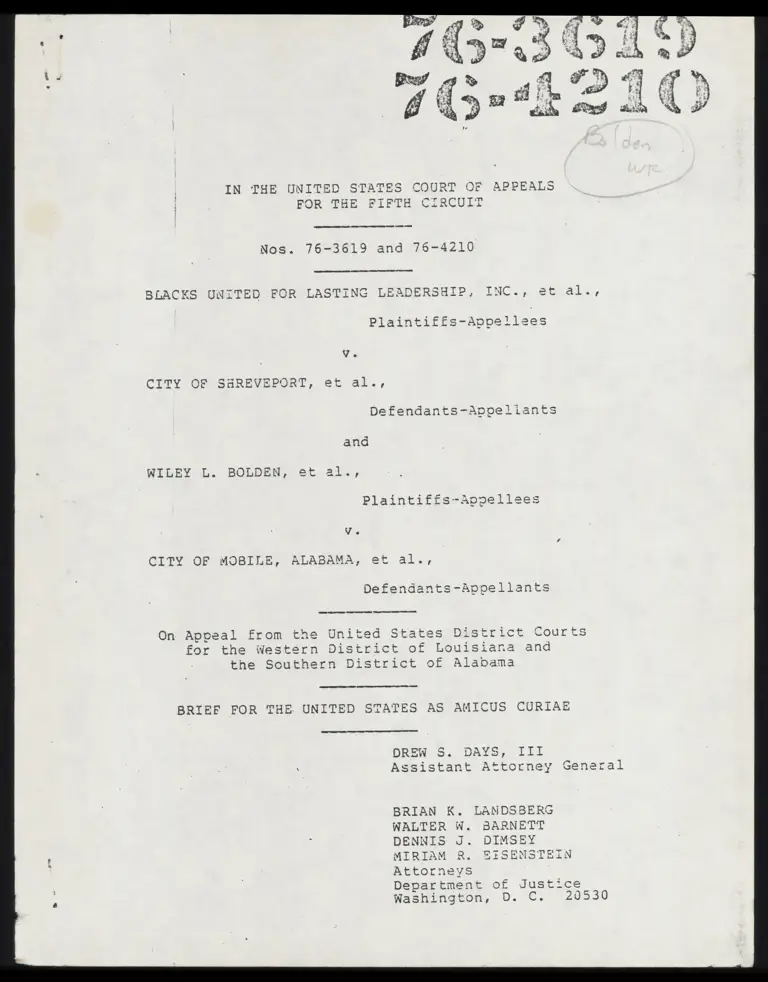

Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

June 6, 1977

77 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1977. 5ad41eac-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/09b56578-7d55-40b4-a0fc-ac8ed8cf847e/brief-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE PIFTHR CIRCUIT

Nos. 76-3619 and 76-4210

BLACKS UNITED FOR LASTING LEADERSHIP, INC., 2t al.,

0 Plaintiffs-Appellze

Defendants-Appeliants

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et 2l.,

H))

Plaintiffs~Appellee

on

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al.,

pellants oO

0]

Hh

M®

pl

0:

fu

3 ct

in

|

To

TU

On Appeal from the United States District Courts

for the Western District of Louisiana and

the Scuthern District of Alabama

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

EW S. DAYS, I11

sistant Attorney General

BRIAN K. LANDSBERG

WALTER W. BARNETT

DENNIS J. DIMSEY

MIRIAM R. EISENSTEIN

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D. C. 20330

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Ld

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ¥en EE

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES al eR RO oP 2

STATEMENT ,ccceccecccscscscsccscsssscsscssesccsscscscsoocscscscsce 3

v. BULL. V. CITY OF SHRRVEPORT .esvesisnsvns 3

A. Procedural HiStOIY ceceeccccecccccccoccse 3

Be FACES ceeecvvsrsssrsresssiasssssvnesenss 4:

C. Opinion of the District Court ...ccce.e.. 8

11. BOLDEN V. CITY OF MOBILE .cvvsenvrsnseeceses 1}

A. Procedural History ead on 11

Bei PBOLE ens ensesdesseesrsssssvesnssnnvenss “14

Cc. Opinion of the District Court ..cceceees 27

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT vse swe thn 29

ARGUMENT see cnotsionsarsssinssonsensmsnsnssrsiteenenas 35

I. THE DISTRICT COURTS CORRECTLY HELD

THAT THE AT-LARGE SCHEMES FOR ELECTING

CITY COMMISSIONERS IN SHREVEPORT AND

MOBILE IMPERMISSIBLY DILUTE BLACK VOTING

STRENGTH IN THOSE CITIES ccccccccccccnscccnne 35

A. The courts below correctly

applied the principles of White

Ve Regester © © © © 9? © 0 9% © © © OO O° OOOO O° OO OOS Oe 35

B. The Mobile court correctly found

blacks were excluded from the

political process SN 0998009080069 86099 0 41

Pd

e

| ants

| PRGE

II. PROOF OF INITIAL RACIALLY DISCRIM-

: INATORY INTENT IS NOT AN ESSENTIAL

ELEMENT IN CASES CHALLENGING AT-LARGE

VOTING PLANS AS DILUTING MINORITY VOTING

STRENGTH vive vr vrtarnins sn sot ss osevrvoeey vanes 45

A. The test under the Fourteenth

‘Amendment is whether a scheme,

designedly or otherwise, minimizes

or cancels out the voting strength

Of 2a racial Minority cevvessescocesvssnes 45

B. The Fifteenth Amendment does

not require proof of official

racial intent in cases challenging

at-large voting plans ..cecccccccncccccns 54

C. If proof of racially discriminatory

intent is needed, it should be

inferred from the facts of the

Shreveport and Mobile cases cceecccccesns 56

III. THE DISTRICT COURTS' ORDERS WERE COM-

PELLED BY THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF EACH

CASE, AND WITHIN THE COURTS' REMEDIAL

"POWERS tt ccececcccecsesetcscscccncesccscccsnsccnce 61

CONCLUSION © © © © © © © © © 0 9 0 OO © © © OO 9 OO OO OO TO OO OOOO SO OOO OO 68

rg

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES | : PAGE

(

Allen v. City of Mobile, 331 F. Supp.

1134 (5.D. Ala. 1971), aff'd, 466

F.28 122 "(5th Cir. 1972), Cert. ;

denied, 412 U.8. 909 (1973) vasvsesvsnrenvons : 24

Anderson v. Martin, :

B15 VeSe IY {19648) cvurvnssnisvssssnsssssnses 43

Atlantis Development Corp. Vv.

United States, 379 F.2d 818

(5th Cir. 1967) ® @ @ © oo © © © © © @ © 9° © © O° 0 OO © OO 0 O° OO 37

Blacks United for Lasting Leadership

Vv. City of Shreveport, Loulsiana,

71 F.R.D. 623 ‘w.D. La. 1976) ® © © © © © © © ® © © © © 8 0 passim

Bolden v. City of Mobile, Alabama,

823 FeSUDD. 38% (S.Ds AlAs 19/0) sievasvssnvies passim

Bradas v. Rapides Parish Police Jury,

508 F.2d 1109 (5th Cir. 1975) © ee 000000000000. 46

Brown v. Board of Education,

345 U.Se 294 11955) cowvcviessn Cohesive an deien ns | 64

Burns v. Richardson,

388 U.Se 3 {1900) wevvesesssnssssossavsosess _ 45

Chapman v. Meier, :

420 U.S. 1 (1975) © © ¢ 0° 0 9° @ O° OO O00 O00 ee 00 eo 45, 51, 56

Connor v. Johnson,

102 U.S. 690 (1971) ® © © ® © © ®@ © 0 © O OO O° OO OOO OO 0 00 36, 51, 62

Cal v. Boren,

U.S. 190 (1976) ® © © @ © 9 © © © © © © © 0 © © O&O © 0 © © O° O° 0 0 51

Dandridge v. Williams, : :

SY] U.S+i 871 A1940Y evn eeve es 6 nvninoieinise enn 50, 54

Dunn v. Blumstein,

505 U.S. 330 (1972) ® ®@ @ ® © @ © © © © © © & © © © @ OO OO 0 © © 0 0 0 5 51

East Carroll School Bd. v. Marshall,

424 u.s. 636 (1970) ee eo 00 ® ® e090 ® 00 ee 0°00 00 00 0 0 36,37,47

. 51

iii

CASES : PAGE

Ferguson v. Winn Parish Police Jury,

EZ F.28 537 (SED CIC. 1976) -evevsevoses

a5

Fortson v. Dorsey, ; .

379 U.5. 433 (1965) ie i Jee ne EE

45, 57

Gomillion v. Lightfoot,

364 U.S. 339 (1960) eo ee 8 8 © @ © @@ © © © 0 © OO © O° 0° 20 50, 52, GO,

pi 63-et seq.

Graves v. Barnes,

343 F. Supp. /04 (W.D.. Tex. 1972),

aff'd sub nom White v. Regester,

412 U.8. 755 (1973) cemecsvesosnvsncnssnss.. 42, 43, 57, 58

Howard v. Adams County Board

of Supervisors, 4353 F 1 455

(5th Cit.¥, cert. denied, 405

U.S. 928 (1972) svesves Te sews ens eens 46

.Jaffke v. Dunham,

352 U.S. 280 (1957) © © © 0 0 © 0 © 0 @ 8 8° eo 0 0 00 00 54

Kendrick v. Walder, |

527 F.2d 44 (7th Cir. 1973) ececececcenccs 29, 65

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors

of Hinds County, Mississippi,

No. 75-2212 15th vir., qecided ;

May 31, 1977) cececenccceccenscccccnccnae 37, 39, 43, 49,

59, 60

Lucas. v. Colorado General Assembly, :

377 U.S, 713 (1Y08) sevsenssensns eesssans 64

McGill v. Gadsden County Commission,

535 F.2d 277 (5th Cir. 1970) eeecececccee 37

Moore v. Leflore County Board >

of Election Com'rs, 502 r.Zd

021 (5th Cir. 1974) vie vie vin sine se Hee. 40, 46

Nevett v. Sides, |

533 F.2d 13601 (5th Cir. 1975) vivitie a6 4h ee : 37

Nevett v. Sides, | ial

appeal pending, No. 76-2951 (5th Cir.) +. cil

iv

CASES : PAGE

Paige v. Gray, :

B38 F.2d 1108 (5th Cire 1978) evesviarnennina 2, 37, 49-50,

; 66-67

Panior v. Iberville Parish School Bd.

536 F.2d 101 (5th Cir. 19706) ® © © @ ° & o. ® © © & ¢ ‘45

. Perry v. City of Opelousas,

515 F.20 B39 (OFN Cire 1975) suv nvrvsnenne 40

Reynolds v. Sims, :

377 U.S 533 (1964) TNE ET Re SR SR Sr to We TR Re 53

Robinson v. Commissioners Court,

Anderson County, oU0b F.<0 014 :

(5th Cir. 1974) ® © © © ® ® © © © © © © © © © © © © O&O © © © 0 O° O° 46

Sims v. Amos, 336 F. Supp. :

924 (M.D. Ala. 1972) ® © @ © © © © © © © @ ®@ & 0 OO © O° 0 0 23

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 402 UeS. 1 (1971) venus coeds 65

Turner v. McKeithen, : |

§90 P.2d7191 (5th Cir. 1973) veceveenmanasi 40

United Jewish Organizations of

Williamsburgn, Inc. v. Carey,

YY UsS.lieW. 422% {U.S. Mar. 1, 1977) wuss’ 42, 48, 55

United States v. City of Shreveport,

7210 F. Supp. 36 (w.D. La. 1962),

affirmed, 315 F.28 928 (5:h Cir. 1968) . a 7

United States ex rel. Barbour v.

District Dir. of 1. &% N.S., :

491 F.2d 573 {5th Cir. 1974) ® © ® ® © @ © © * © © 0° 54

Vandenades v. United States,

523 F.2d 1220 {oth CIT. 1975) ® @ © © © © o @ 0 0° 37

Village of Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Development

Corp., 45 U.8.L.W. 4073 (U.S.

JAN 11, 1977) sneer sessmavsossssnnsroneinse 32, 33, 35,

: 47, 49, 54,

56, 57, 59, 53

CASES | PAGE

Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d

619 (5th Cir. 1975), cert.

granted, judgment vacated and

remanded, 425 U.S. 947 (18976) cevevvesconsiesed, 28, 37,

40, 46, 47

Wallace v. House,

538 F.2d 1133 (5th Cir. 1976) © ® oa e000 0 00 0 00 oe 37

Washington v. Davis,

426 J.S. 229 (1976) © ® © © 0 00 @ @ 0 000 000 ee O00 00 28, 32, 33,

35, 47, 49,

50, 54, 56,

59, 63

Whitcomb v. Chavis,

303 T.5." 124 T1771) cnenese PEIN NEI NC ra passim

White v. Regester, :

12 U.80 155 1973) avant svnsnsesnisnanenssess passim

Wright v. Rockefeller,

370 DSc 527(1964Y vue vvese sasisns se vaeiesreeey 48,:49, 52

Wright v. Rockefeller,

211 P., Supp. 460°

{S.D. N.Y. 1962) ® © & & © oo oo ®@ @ © © &@ © © © @ © © © © © & © © © 0 49

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, . ;

T15 U.S. 358 (1586) uc evsnivevs te ein ein eie sen 52

Zimmer v. McKeithen,

485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973),

affirmed sub. nom East Carroll

School Bd. v. Marshall, 424 4.8.

636 (19706) eee ceo eee FEE ar CO OI MRE GPE passim

UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION

First MmenIGMmenlt .eeceess esses sssrsrssnes Cheese 11

Fifth Amendment SI ON PE NM TNE CE Pi td 54

Thirteenth Amendment Gees cvsersvsonsrsneoniovns 11

Fourteenth Amendment ® © @ © © © © © © @ © © O° © © © O © °° 0° °° O° 0 passim

Fifteenth AMeNAMENE vd vos casnsrssssensvasesves passim

vi

STATUTES

28

42

- 42

42

u.s.cC.

U.S.C.

¢.5.C,

u.s.c.

u.s.cC.

2201

1971

1973

19737

eo @ oe &@ © © © 0°

® © © 0 © 0 @ © @ @ oO 0

© © ® © 6 © © 0 © @ © 0 ¢ Oo 0

® eee @ © 0° © 0° OO 0 0 0

0.8.C. 1073340) eesvinvrssrrsnserssons 3

¥.8.C. 11983 4,

© ® © © © © © © © ® ®@ © © © 9 OO 6 0 ee 0 0 0 00

42 U.S.C. 1985(3) ceecececcccacccccccccac

-

STATE STATUTES

Ala. Act.281 (1911) @e © © © @ © © © © ® © © © O° © © @ 0 O° 0 0

Ala. Act 823 (1965)

la. R.S, 18:358 ... “rune 5

La. Act 302 (1910)

FEDERAL RULES OF CIVIL PROCEDURE

Rule 52(a) 30, 41

© ® © 9 © 8 8 © © 9 © 0 OO 0 8 OT OOS OOO 00 ee 000

RULE ZU DI IY rants eines r cows vnnvassdicnevie 12

MISCELLANEOUS

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of

Population Characteristics, Final

Report PC (1) - B2, Alabama,

Table 24 18

vii

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

¥

Nos. 76-3619 and 76-4210

BLACKS UNITED FOR LASTING LEADERSHIP, INC., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees

Ve

CITY OF SHREVEPORT, et al.,

Defendants—Appellants

and

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

Plaintiffs—-Appellees

Ve

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al.,

Defendants—-Appellants

7

On Appeal from the United States District Courts

for the Western District of Louisiana and

the Southern District of Alabama

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the district courts correctly ruled that the

at-large systems for electing the city commissioners of Shreve-

port, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama, unconstitutionally dilute

black voting strength.

- .

2. Whether the district courts erred in failing to

require proof that the at-large voting YAS in question

were adopted with racially discriminatory purpose or motive.

3. Whether the courts' remedial orders, which effectively

preclude the use of strict commission governments in Shreveport

and Mobile, were within the scope of their equitable powers.

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES

Congress has placed upon the Attorney General important

responsibilities for protecting the voting rights of United

~ States citizens. The Attorney General is authorized by 42 U.S.C.

1971 and 1973j to institute actions to prevent the denial of

the right to vote on grounds of race or color. Although

these actions were instituted by private parties, resolution

of the issues presented will directly Affect ule authority

of the Attorney General to protect the voting rights

of Americans citizens. See, e.g., Paige v. Gray, 538 F.2d

1108 (5th Cir. 1976).

- 3 -

In addition, Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C. 1973c¢c, requires the submission

of changes in voting laws of covered jurisdictions for the

purpose of obtaining clearance of such changes from either

the United States District Court for the District of

Columbia or the Attorney General. The Attorney General

is authorized by Section 12(d) of that Act, 42 U.S.C.

1973j(d), to institute an action to prevent a change from

being implemented unless it has been cleared pursuant to

Section 5. In 1976, the Attorney General interposed an

objection to Mobile's change from at-large elections for

three undifferentiated city commission “places” to at-large

elections for three ‘functional commissioners.

STATEMENT : ;

I. B.U.L.L. Vv. CITY OF SHREVEPORT

A. Procedural History

This action was commenced in March 1974 by black

individuals and organizations in Shreveport, Louisiana.

The complaint, which named as defendants various city and

state officials, charged that the at-large system for the

election of Shreveport's city commissioners impermissibly

* . -4-

diluted black voting strength in violation of the Four teenth

and Fifteenth Amendments. PL2intizes wought GeslAratory and

injunctive relief pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 2201 and 42 U.S.C.

1983, including an order requiring the defendants to submit

a oi dbs plan apportioning Shreveport into five single-

member districts.

Three days of evidentiary hearing were held in May

1974. The hearing was postponed pending resolution of

the question whether a three-judge court was required

to hear the case. In September 1974 the court ruled that a

court of three judges was unnecessary. Two more days of

evidentiary hearing were held in April 1975, On July 16,

1976, the court issued an opinion in which it declared

Shreveport's election scheme unconstitutional. Judgment

was entered July 27, 1976. Defendants appealed.

On December 27, 1976, Blainsitte-aApgelises filed a

motion to dismiss the appeal on the grounds of mootness

and the non-appealability of the district court's order.

This motion was denied by this Court on February 14, 1977.

That same day, the Court ordered the case consolidated with

1/

Bolden v. City of Mobile, Alabama.”

B. Facts

The facts are set forth in detail in the district court's

opinion (pp. 6-16), in appellants' brief (pp. 8-12), and in

appellees' brief (pp. 7-13). Essentially, the evidence showed

1l/ The United States learned only recently that the court had

ordered Nevett v. Sides, No. 76-2951, to be argued in conjunction

with B.U.L.L. and Bolden. Because we did not have sufficient

time to prepare a brief for the Nevett case, this brief

addresses only the B.U.L.L. and Bolden cases.

“5

that Shreveport has functioned under a commission form of govern-

ment since 1910. In 1950 Shreveport adopted a city charter that

continued the basic commission government under which it had been

operating. The charter provides for five commissioners, each of

whom is elected at-large. Each commissioner, including the mayor,

heads one or more of the city's departments. In addition, the

commissioners act as the city's legislators. Most of the

conaleeionsrs! working hours are spent on executive sitters |

Primary elections in Shreveport are governed by Louisiana's

"majority primary law" {La. R. S. 18:358)., Candidates must

run for a designated commissionership, and there is no

residency requirement (other than city residency). There is

no official candidate slating process in TI Poten-

tial candidates usually consult with city leaders before

4/

deciding whether to run.

5/

6/

Although blacks constitute 34% of Shreveport's population, .

Voting in Shreveport is polarized along racial lines.

no black has ever been elected a commissioner. Only one

4

black has run for a commissionership; blacks have been

discouraged from running for office by the inevitability

2/ T.1 59. {T.1 refers to the transcript of proceedings

Tor May 2, 3, and 30, 1975; 7.11 refers to the transcript

for proceedings for April 21 and 22, 1975.)

3 2.1123, 58, 119.

4/ T.I 40, 68, 216.

5 7.1130, 212; T.11 8-11, 157-158, 169-170.

8/ T.11 32.

- 6 =

8/

of defeat. In only a few instances "have blacks been

able to affect the outcome of an election by tipping the

9/

balance in favor of one of two white candidates. However,

the support of black voters is sought by candidates for

10/

the office of city commissioner.

11/

Housing in Shreveport is racially segregated.” 0il-

base streets in black neighborhoods are permitted to lapse

12/

into disrepair; drainage in black areas is poor. Police

protection and garbage collection in the black community

13/

are unsatisfactory. The city has failed to provide

. 14/

adequate low-cost housing for blacks.

8/ T.1-2), 150-131,

9/ P.1 6l.

xo/ T.1.37, 215,.227; 7,11 100-101, ‘120, 201.

11/ Deposition of Professor Karl E. Tauber.

12/ T.I 11-12, 80, 92, 100-101, 104-106, 176. However, the

city recently allocated $500,000 for the improvement of

drainage in black neighborhoods. T.I 66, 94, 220; T.II

325, 215,

13/ T.1 49, 64, 115-116, 142, 149, 169-170, 179, 183,

203-205; T.II 112.

14/ T.I 162-163, 193-196.

Hk, Ti

The city's record in minority employment is poor, and

only recently have blacks been appointed to official

committees under the city commit 85.9 per cent of

all nynek lotiv employees earn less than $6000 a year,

while only 18.7 per cent of all white city employees earn

less than that amount. 82.7 per cent of all black city

employees are classified as “service maintenance,” the

city's lowest job classification; only 13.7 per cent of all

white employees are. so tasetbist in

Blacks in Shreveport have been the victims of official

racial discrimination in the voting Srocess. 1H addition,

under state statutes and local ordinances, they Have

been required to attend segregated schools and to. use

segregated public accommodations, recreational facilities,

: 18/

conveyances, restrooms, and water fountains. .

i5/ 7.1 65, 112-113, 115, 134, 153-154, 225: 2.11 35-40.

Yeé/ 7. 11 40.

17/ T.1I 73-74; answers to interrogatories of J. Stanley Pottinger,

Assistant Attorney General, Civil Rights Division, United States

Department of Justice.

18/ See, e.g. United States v. City of Shreveport, 210

F. Supp. 36 (W.D. La, 1967), affirmed, 316 F.2d 925

(5th Cir. 1963) (City of Shreveport and its commission

council permanently enjoined from operating racially

segregated rest rooms and dining facilities in the Shreveport

- Municipal Airport).

- 5

C. Opinion of the District Court

The district court found for the plaintiffs. The court

peld that "the commission-council form of municipal government

in Shreveport, requiring thé at-large election of all commissioners,

within the framework of facts and circumstances peculiar to this

city, Her AEN impermissibly to dilute the minority voting strength

of black electors" (Blacks United for Lasting Leadership, Inc..,

{*"B.U.L.L.") v. City of Shreveport, Louisiana, 71 P.R.D. 623,

627 (W.D. La. 1976)).

The court relied principally upon the Supreme Court's

decision in White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973). The

court also cited -- as "giv[ing] us insight into the con-

trolling principles of law by which we ... are guided”

(id. at 633) -- two recent cases decided by this Circuit:

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (1973) (en banc), affirmed

on other grounds sub nom. East Carroll Parish School Bd. v.

Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976), and Wallace v. House, 515 F.248

619 (1975), cert. granted, judgment vacated and remanded, 425

U.S. 947 AT These cases identified a number of factors

to be considered in determining whether an at-large or

multi-member district voting scheme impermissibly dilutes

minority voting strength in violation of the Equal Protection

Clause. The district court considered each of the

‘relevant factors. Its findings as to these factors are

summarized as follows:

19/ The court stated, "[OJur decision today does not stand

or fall upon the constitutional orinciples axpressed in

Zimmer, but rather upon those announced in White v. Regester,

D.

supra, and authorities there cited.” B.U.L.L., supra, 71 PF.

at 633-634, n.l17.

“GQ w

1. Lack of Opehness of the selitical Process. No

black has ever been elected to the city office in Shzevepdrt.

Only one black has ever run for a Shreveport commissionership.

“[B] lack persons plainly have been discouraged from seeking

office by [the] inevitability of defeat" (id. at 628; foot-

note omitted). The support of black voters is actively

sought by candidates in city elections, and black voters

sometimes have been able "to tip the balance in favor of

either of two white candidates” (id. at 635). The court,

however, did not consider this “the sort of meaningful

access to political processses intended by the Fourteenth

Amendment as interpreted in White [v. Regester]" (ibid.)

2. History of Racial Discrimination. The court

found that "official racial discrimination ... long

[has] affected all aspects of the lives of Shreveport's

black citizens" (ibid.). “Housing in the city remains

almost totally segregated[;] residual effects of past

discrimination linger in public employment[;] [b]lack

voter registration percentages remain lower than proportionate

white registration" (ibid.; footnote omitted).

3. State Policy Underlying Use of At-Large Voting.

Blacks were disenfranchised in 1910 when at-large voting

for city commissioners was instituted in Shreveport.

The court therefore perceived no "tenuous policy" underlying

= “10 —

| 20/

the use of at-large voting (ibid.).

- 4, Responsiveness to the Black Community. The court .

found that “in the past, local officials clearly neglected

their responsibilities to the needs of black persons in

the community. Recreational facilities were completely

segregated and those in black neighborhoods inevitably

were inferior. Blacks were not appointed to committees

and boards of local importance, and the record of black

employment by the city was, and still is shameful. Finally.

governmental services and facilities generally were

disproportionately poor in the black neighborhoods" (id.

at 635-636). |

The court perceived “at least some sincere efforts

to achieve racial fairness in dispensing public benefits”

(id. at 636). Nonetheless, the court ruled, “the record,

in clarion tones, bespeaks many still lingering failures

remaining to be rectified" (ibid.).

5. Enhancing Factors. The court found that “[t]lhe

majority primary law, 'place' requirements, [the] absence

of residency requirements, and racially polarized voting

all have sracerbated the past almost total foreclosure

of blacks from truly effective exercise of the ballot" (ibid.).

20/ There is no “strong state policy," Zimmer v. McKeithen,

supra, 485 F.2d at 1305, underlying the use of the commission

orm of government in Louisiana. State law permits, but

does not require, the use of this type of government. See

Act 302 of 1910.

- 11 -

On the basis of these findings, the court held

that the relevant portions of tie city charter "operate

impermissibly to dilute the. voting power of the city's

black electors in violation of the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment” (id. at 636).

The court did not order specific changes in the city

charter. Rather, it required the defendants to submit

within one year proposed revisions to the charter

“to bring it into compliance with the constitutional

principles [it had] articulated" (id. at 637). =

1X. BOLDEN v, CITY OF MOBILE

A. Procedural History

This action was commenced on June 9, 1975, by black

voting-age citizens of Mobile, Alabana, against the City of

Mobile and the three incunBent city conn ssioners in their

individual and official capacitor Shpt elation alleged that

the system of electing the city commission at-large, to numbered

places, discriminated against the black voter minor ity, and

diluted their vote, thus violating plaintiffs' rights under the

First, Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, and

21/ The court did not require that the Mayor be elected

from a single-member district. It stated, id. at 636, that

»{o]f course, as Chief Executive Officer of the City,

‘necessarily the Mayor must be elected by voters in an

at-large election city-wide."

22/ R 1. Appellants in Bolden have elected to proceed with a

deferred appendix. Citations here to the record will be

made by the designation “R _;" "Tr. " will signify citations

to the trial transcript. Exhibits will be identified as "Pls.

Ex. mal and “"Defs. EX. RANG by number and, where relevant, page.

TE a

-12 - ;

23/

42 U.S.C. 1973, 1983, and 1985(3). ‘They prayed the court for

a declaratory judgment and an order enjoining further

elections under any plan other than one implementing single-

24/

member districts. After the court denied the defendants’

motion to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction and failure to state

25/

a claim, and motion to strike plaintiffs' prayer for in-

26/ :

junctive relief, the defendants filed an Answer denying

27/

all material allegations of Complaint, including plaintiffs’

class allegations. On January 19, 1976, the district court

certified the plaintiff class, pursuant go mule 23(b)(2),

Fed. R. cio Bl, as "all black persons who are now citizens of

the City of Mobile." 2% |

After extensive discovery, trial was held in July. 1978,

At the completion of trial, prior to entering findings, the

23/ R 1-3. The district court subsequently dismissed plaintiffs’

T1983 claims against the City defendant, and the 1985(3) (conspiracy)

claim against all the defendants, R 171-172.

24/ R 3. | et

25/ R 19-20 (Motion to Dismiss).

26/ R 21-22; Motions denied, R 170-173, November 18, 1975.

27/ R 184-189 (December 3, 1975).

28/ R 333.

A

-l3~

district court asked the defendants fo submit alternative single-

member district mayor-council plans ih case the court should

: 29/

decide in favor of the plaintiffs.” The. plaintiffs submitted

a nine single-member district plan but "the defendants chose

| | 30/

not to avail themselves of this opportunity." Thercfore, the

court requested and received recommendations from the parties

for three persons to constitute a committee to draft and recommend

3Y/

to the court a complete mayor-council plan. - On October 6, 1976,

the court appointed the three-man committee and asked them to

: ; 32/

complete their recommendation by December 1, 1976. On October

: 33

22, 1976, the district court entered judgment for the ovlaintiffs,”

ordering that the August 1977 city elections be conducted and

council members elected from nine single-member districts pur-

suant to a detailed plan yet to be adopted. Defendants filed a

| 34/ :

notice of appeal on November 19, 1976. = On March 9, 1977, the

district court entered its remedial order spelling out the plan

35/

for a new form of government and elections. Because there was

doubt as to the finality of the court's October 22, 1976, judg-

36/

ment, defendants filed a second Notice of Appeal, March 18, 1977+

29/ Pr. 1415 (July 21, 1976). Plaintiffs had already submitted

plans pursuant to the pre-trial order (id., 1414-1415). N

30/ Bolden v. City of Mobile, Alabama, 423 F. Supp. 384, 404

(S. D. Ala. 1970).

31

/: Ibid.

543-544 (Langan, Outlaw, Buskey).

604-606.

R

R

34/ B® 613,

R 622-627.

R 681. Appellees' brief (footnote continued on next page)

- 14 -

Me oY,

B. Facts

In Alabama, the form of government olch city must

(or may) adopt is prescribed by state law. Between 1844 and

1911, Mobile most often functioned under a "hybr id" system of

at-large coutiol Inentand aldermen elected from multi-member

Sistrintinl The three person commission-type municipal government

was adopted in 1911 by Ala. Act. No. 281 (1911)(at p. 330).

The system requires each commissioner-candidate to run for a

numbered post and win a majority in a non-partisan election

(without first winning a primary). There are no residency re-

quirements other than residency in the City of sopiiel

While elections to the city commission have always been

at-large to numbered posts, it was only in 1965 that specific

40/

functions were assigned to each post by statute. After this

(footnote continued from previous page) informs us that on

April 7, 1977, the district court granted the Commissioners’

application for a stay pending appeal, and that a motion to

dissolve that stay is pending in this Court, brief, pp. 6-7.)

37/ The facts are spelled out in the district court's opinion,

423 F. Supp. at 386-394, and in the appellees' brief at pp. 7-24.

38/ See, generally, appendix A to appellants’ brief, outlining

the history of Mobile city government.

39/ 423 F. Supp. at 386-387.

40/ 423 F. Supp. at 386.

-15 ~-

action was commenced, the City of Mobile submitted Act 823 of

(

Alabama (1965), instituting functional posts, to the Attorney

: 41/

General pursuant to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

On March 2, 1976, the Attorney General (per Assistant Attorney

General Pottinger) interposed an objection to the change on the

42/

ground that it tends to lock in the use of at-large elections.

ee«[Ilncorporating as it does the

numbered post and majority vote features,

and in view of history of racial discri-

mination and evidence of bloc voting in

Mobile, we are unable to conclude... that

section 2 of Act No. 823 will not have the

effect of denying or abridging the right

to vote on account of race or color. 43/

The objection letter explicitly noted that the move to functional

RE, would make it impossible for the city to change to single-

member district voting, as it would be inappropriate to give

one segment of the city exclusive right to elect, €.g9., the

commissioner of sotice. vo suit has been brought in the

District Court for the District of Columbia +0 challenge this

objection.

It is undisputed that the commission form Bs eanent was

adopted in what the court labeled a "race proof" context because

the 1901 Alabama Constitution had already disfranchised blacks.

41/ R 472-477.

"42/ R 478-481.

43/ R 479.

44/ Ibid.

45/ 423 PF. Supp. at 397.

“16 ~

Plaintiffs' historical expert, Dr. McLaurin, however noted

that: (1) the reformers who brought about the commission form

of government to end "corruption" identified corruption with the

black vote; (2) they were aware that at-large elections would

diminish the impact of any potential future black vote; and,

(3) blacks, in any event, were excluded from the decision to

46/

adopt ehts form of city government.

The city has had the option to discard the commission

form of government by referendum but, under state law, the

available alternatives have been a return to the pre-1911

system or adoption of the so-called "weak" mayor-council

system. ¥ Referenda to change the form of government in

Mobile rejected those options in 1963 and 1973.2

As a practical matter, the power to pass or veto bills

modifying the form of city government resides in the city's

delegation to the State Legislature. Mobile has three senators,

any one of whom can veto proposed local legislation under

the existing courtesy rule. A majority of Mobile's

46/ Tr. 21-25, 38. The district court made an explicit finding

as to the second of these points, 423 PF. Supp. at 397: "A

legislature in 1911 ... should reasonably have expected that

the blacks would not stay disfranchised. It is reasonable to

hold that the present dilution of black Mobilians is a natural

and foreseeable consequence of the at large election system

imposed in 1911."

47/ See, generally, 423 F. Supp. at 404; Edington dep. (Pls.

Ex. 98), pp. 41-43, 68. :

48/ vr. 335, 734, 737: Ple. Ex. 98, p. 41,

- 17 =-

eleven-menmber House delegation can prevent a local biil

from reaching the floor for debate.

After this suit was filed, a bill was introduced to the

State Senate to make a strong mayor-council Soeted an option

the City of Mobile could adopt by referendum. It would provide

for an at-large-elected mayor, seven council members from

sinalemenbet Alek tots; and two council members at-large.

The pill has been held up by the "veto" of a single state

senator. At a meeting of civil leaders, a white Moble

leader expressed the view that this bill threatened

“majority" rule. 2Y Similar bills have been intro-

duced calling for single-member district elections for

county commission and county school board. Black state

49/ 423 F. Supp. at 397.

50/. Tr. 726-736 (Roberts); see, also, Pls. Ex. 98, p. 30.

--18 ~

representative Cain Kennedy testified that-the question most

often raised in opposition to both wag: how many blacks

| 51/ :

might be elected.

Blacks constitute approximately 35.4% of Mobile's popalation

of over 190,000. 22/ he black percentage of the City's voting

age population is 318.2 The percentage of registered voters

who are black is even Yovor 2 sn black turnout regularly

lags behind the already low white A, ad

Extensive evidence was introduced to show the degree to

which voting in Mobile has been polarized along racial lines.

. Plaintiffs made use of the correlation analyses done by defen-

56/

dants' expert, Dr. Voyles, .in his doctoral dissertation,” and

: 51/

correlation studies by their own expert, Dr. Cort B. Schlichting.

s

51/ Kennedy dep. , Pp. 28-29, See, also, 423 F. Supp. at 397.

52/ 423 F. Supp. at 386.

53/ U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Population Charac-

teristics, Final Report PC(l)-B2, Alabama, Table 24.

54/ 423 F. Supp. at 386; 89% of the voting age white population

1s registered, but only 63.4% of the black voting age population

is registered.

S5/ Pls. Exs. 3 through 5.

56/ Pls. Ex. 9, “An Analysis of Mobile Voting Patterns,

1948-1970."

51/ Tr. 92-194 and Pls. Exs. 10-53.

-19 -

The basic scheme of these correlation analyses is as follows:

if there are two wards, one 100% black and the other 100%

white, and 100% of the vote in each goes to opposite candidates,

the correlation between race and voting would be 1.0 and race

would account for 100% of the voting behavior. No candidate

ever produces such a correlation, of course, if for no other

reason than that no ward is 100% black or white. Any correlation,

city-wide (or county-wide) over .7 is statistically Re

By an accepted mathematical formula, a "Pearson's R" (like .7)

3 59 /

accounts for 49% (R ) of the voting behavior. =~

‘ The career of Joe Langan, white, long time finance commissioner

long identified with black interests, furnished the only significant

data with respect to city commission elections, for no blacks ran

for city commission until 1973, and then, as minor candidates.

Langan ran for the commission and won in 1953 and thereafter,

every four years until he was defeated in 10892 besos ing to

Voyles' tables and analysis, Langan began as a New Deal Democrat

who won, at first, with a coalition of the white and such black

vote as arated Beginning in 1961, a polarization became

apparent between the lower and lower middle class black wards on

: 62/

the one hand and the equivalent-class white wards.

58/ See e.g., Tr. 159 (Schlichting).

S59/ Pls, Ex. 9, Ch. 1V.

60/ See Pls. Ex. 9, pp. 82-99,

61/ 1d. at pp. 82-84 and table at p. 87.

62/ 1d. at pp. 91-93; in 1961, Langan won 94.31% of the yote in

Fhe lower-black wards and 91.30% of the lower middle black; the

overall correlation was .71 for race.

- 20 ~-

; 63/

The gap widened with each successive election, so that in

1969 he won 94.39% of the vote in the lower-middle black wards

but 34.35% in the lower-middle white wards, for an overall

64/ :

correlation of .91. Campaign literature openly identified:

Langan with the so-called "bloc vote" (a code for blacks)

and with John LeFlore, well known black leader in Mobile. hg

One flier, challenging the voters: "Bloc Vote or Youz",

lists five ways in which the bloc vote is obtained, e.g...

favoring integration and open housing, and using terms of

66/

respect when addressing blacks.

At trial, there was considerable debate regarding the

role played in the 1969 Langan defeat by the unusually low

67/

black turnout. No one, however, disputed that this election

’,

represented the high water mark of racial polarization.

(o)

]

bi

o,

3 See, id., pp. 93, 99,

oN

~N

4 Id., p. 99; Pls. Ex. 53.

65/ Pls. Bx. 61, po. 48, (ad): 55 (flier); 49

{political ad); 56 (flier); 58 (flier); 59 (flier).

66/ Id., p. 56. The flier also lists black ward votes for

Langan in the past. 9

67/ Tr. 295-305 (Langan); 481-482, (Voyles).

- 21 -

Indeed, the winners in the 1969 city commission race,

68/

generally, carried no black wards, and though Langan carried

some white wards, he failed to carry any group (e.g., lower,

69/

lower-middle) of white wards.

In 1973, by contrast, blacks ran for two of the three

city commission slots. They were relatively unknown and

underfinanced, and garnered relatively few votes even in the

predominantly black wards. On the other hand, they received

70/

their only votes in the black wards. Race was not manifestly

‘a factor in 1973 as between the white candidates. Doyle had run

unopposed. Mims had prevailed without a run-off, with a Pearson's

71/ : : 72/

R of .71, and Greenough beat Bailey with a Pearson's R of .59.

The black vote, however, went more heavily to loser Bailey than

73/

winner Greenough.

68/ Tr. 460 (Voyles).

69/ Tr. 491 (Voyles).

70/ Pls. Exs. 48 and 53 (Taylor's R); Pls. Ex. 47

(Smith's R). Cooper dep., Pp. 15 (Pls. Ex. 99).

11/ Pls. Ex. 53, (Voyles' Pearson's R).

12/ Pls. Ex. 53, using Voyles' data. . Pls. Ex. 46

shows a correlation of only .51.

73/ Defs. Ex. 29; Tr. 1133-1134.

om 22 -

The city commission races of 1961 and 1965 other than

the ones trvolving Langan show only moderate correlations

between voting and race, at least by compar ison to the Langan

races. The only consistent feature is that the majority of

| 74/

the black vote went to losers.

Significant correlations between race and voting appeared,

however, in five county school board primary run-off

: : 75/

elections in 1962, 1966, 1970, 1972, and 1974. In four of these

elections, a black candidate ran against a white. In the fifth,

the 1972 race, a white woman, Koffler, who was highly identified

with desegregationist interests, was defeated by a white man

with opposing stevens The highest correlation was that in 1966,

where a black, Russell, lost to 2 White fa a contest polarized

.96 by race.

Finally, in 1972, Langan made a run for the Democratic

nomination for County Commission, and lost in a run-off in

18/

- a heavily polarized vote (.86). As in 1969, Langan's opposition

publicized in detail the candidate's popularity with the “bloc

74/ Defs. Ex. 33; Pls. Fxs. 9 and 53. Note that Voyles'

findings of high correlations by race are offset by almost

equal correlations based on income. Schlichtings' correla-

tions for Mims v. Luscher (Pls. Exs. 16 and 18) is only .6753.

15/ Pis.:Px."10, 18, 34, 36, and 52.

76/ Tr. 374-378 (Koffler).

17/ Pls. Ex. 19.

-18/. Pls. Ex. 43.

- 23 =

vote," his identification with John LeFlore's Non-partisan

72/

Voting League, and his anti-Wallace stances in the 1960s.”

Ca " 80/

There was no.black boycott in this election, though the

81/

black turnout was very low.

No black or candidate identified with blacks (other than

Langan) has ever won an at-large election in the City or Ccunty of

82/ :

Mobile™ and many witnesses, black and white, testified that they

83/

believed it would be futile for a black even to attempt to run.

Moreover, witnesses experienced in local politics indicated that

while Non-partisan Voting League (i.e., black) endorsement could

be helpful to a sandidater te conspicuous black support has

been and will continue to be a "kiss of death" to a Gantt iat

Blacks can be, and were elected to the State Legislature after

single-member districts were introduced, but even as late as

1974, black candidate Buskey lost to a white in a closely con-

tested, highly polarized State Senate race. This campaign, like ~

, B86/

others before it, featured racially oriented publicity.

79/ Pls. Ex. 61, pp. 10, 14, 16.

80/ Tr. 311.

8l/ pris. Ex. 3.

82/ State legislature elections were alsc at-large until Sims

Vv. Amos, 336 F.Supp. 924 (M.D. Ala. 1972).

83/ Pr. 209-210 {Bolden):;237, 246-7 (Buskey) ; 410 (Hope); 594

{Alexander); Pls. Ex. 98, p. 38; Tr. 566-567 (Wyatt).

84/ Tr. 213-214 (Bolden); 275 (Buskey); 567 (Wyatt); 322-323

(Langan).

85/ Tr. 141, 193 (Schlichting); 460-463 (Voyles); 227-230, 235-6,

253 (Buskey); Edington dep., pp. 8, 10, 15-17; Kennedy dep., Ppp.

8-11, 20. i 3

86/ Tr. 223-229, 236 (Buskey, re Buskey-Parloff campaign).

The district in question is evenly divided between black and

white with blacks possibly having a slight majority, Tr. 226.

- 34

It is undisputed that between the turn of the century and

1965, blacks suffered from extensive official .and unofficial

discrimination and ‘intimidation, inhibiting their rights

to vote. This history is reviewed in the district court's

opinion and need not be repeated here.

In addition, the city government of Mobile has been unresponsive

to the interests of blacks. Desegregation of such public facilities

as public transportation, the golf course, and the airport, have

all been achieved by federal court ot8eis 2 sintunt in, it required

a federal suit to end Pacial discrimination by the police depart-

parti a City had segregated fire departments until the late

1960's, and at the time of trial, of 439 firemen, 27 were b1ack="

The City's EEO-4 reports to the federal Sevdpnneni sho that

blacks represent about 26% of the City's work force, but they

are heavily concentrated in the lowest service and maintenance job

categories.

87/ 423 Pp. Supp. at 387, 393.

88/ 1d. at 389.

89/ 1bid. {Allen v. City of Mobile, 331 PF. Supp. 1134 (Ss. D.

Ala. I971), B2cTq., 408 F.2d 122 (oth Cix. 1972), cert. denied,

412 U.S. 909 (1973)).

90/ Tr. 1403-1405 (Edwards).

91/ As analyzed in Pls. Ex. 73.

- 25 -

Blacks have minimal representation on the many boards

and committees appointed by the Commission to help run the |

city, amounting to about 10% of the total membership at the

time of WORE a on many of these boards requires

a certain technical expertise or skill. Yet, Commissioner Mims,

on Cross examination, said that the commission limits the field

from which such appointments are made even when not required by

statute to do so. Moreover, in most instances, he was able to offer

no explanation for the absence of blacks from boards, and denied

believing there were no blacks qualified to sete ln, one in-

stance, that of the now-defunct citizens advisory committee

on the Donald Street Freeway, Mims testified that the large black

representation was probabably due to federal regulations regarding

board membership in federally assisted highway oregon

In 1973, the local NAACP complained to the United States

Department of Treasury that federal revenue sharing

92/ Pls. Ex. 64.

93 Tr. 942-997.

94/ Tr. 948-949 and Pls. Ex. 103.

- 26 ~ :

lh

; 95/

funds were being allocated in a discriminatory fashion.

The Office of Revenue Sharing (ORS) made an investigation, and

reached the conclusion that there were a number of inequities in

the allocation of revenue sharing funds, particularly in park im-

provements, paving, resurfacing, drainage, and swimming pools.

After. considerable negotiation, ORS was satisfied that Mobile

had rectified the inequities, or at least had made commitments

to doing 0.”

In the spring of 1976, two major racial incidents

occurred. | One was a “mock lynching” of a black burglary

suspect carried out by a group of policemen; the second

was an outbreak of cross-burnings. The speed with which the

city rdacted to the first of these was a matter of debate

ria Police Commissioner Doyle advised that while

he deplored such activities, he felt he had no obligation

to say so publicly. 2%/ Public Works Commissioner Mims

testified that he, too, deplored cross-burnings, thought people

could do what they pleased on their own property, and would not

95/ Pls. EX. 111 *“D."

96/ Pls. Ex. 111 "X" (January 1974 letter).

97/ Tr. 7155-761, 794-805 (Doyle). The district court concluded,

423 F. Supp. at 392, that the city's reaction was “timid and

slow.”

98/ Tr. 767-768, 804-806.

. i JT

oppose an ordinance to probibit burning anything, crosses or

199/ of

trash, on public property. The district court concluded, 423

(

F. Supp. at 392:

The lack of reassurances by the city commission

to the black citizens and to the concerned white

citizens about the alleged "mock" lynching and

and cross burnings indicates the pervasiveness

of the fear of white backlash at the polls and

evidences a failure by elected officials to take

positive, vigorous, affirmative action in matters

which are of such vital concern to the black people.

C. Opinion of the District Court

On October 21, 1976, the district court entered detailed

findings of fact and conclusions of law, now reported at 423 F.

Supp. 384. Following the lines of factual and legal analysis

prescribed by White v. Regester, supra, and this Court's opin-

jon in Zimmer v. McKeithen, supra, the court found:

1. The history of racial discrimination in Alabama

generally, and Mobile, specifically, combined with polarization

of the vote along racial lines and the at-large structure of

city elections have left blacks with no reasonable expentaLion

of electing blacks or persons identified with plack interests

to the city commission, and have discouraged qualified black

candidates from entering city commission races, 423 F. Supp.

at 389, 393, 39%;

2. The Mobile City Commission has been and continues to

be unresponsive to the needs of black citizens. This has

manifested itself in the city's resistance to desgregation of

public employment and public facilities, reluctance to ap-

point blacks to the City's governing committees, and making

99/ Tr. 1021-1022.

- 28

only a “sluggish and timid response" (id. at 392) with respect

to cross-burnings, police brutality, and other issues of par-

ticular concern to the black community, id. at 389-392, 400;

3. The potential for dilution of the black vote is enhanced

by the size of the city as a multi-member district, lack of a

residency requirement (other than city residency), and the majority

vote requirement for each place on the city commission, id. at

401-402;

4, State law has evidenced no strong preference for

commission government, id. at 393, 400-401.

On the basis of these findings, the district court

concluded that, id. at 402,

«..[Tlhe electoral structure, the multi-

member at-large election of Mobile City

Commissioners, results in an unconsti-

tutional dilution of black voting strength.

It is “fundamentally unfair," Wallace [v.

House], 515 F.2d [619,] at 630 [vacated

on other grounds, 425 U.S. 947 (1976)]

and invidiously discriminatory.

The court also held, as a matter of law, that the Supreme Court's

decision in Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), had not

overruled, superseded, or modified the standards for proving unlaw-

ful dilution set forth in White, supra, Zimmer, supra, or Whitcomb

v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971), and that initial discriminatory

purpose is not an essential element in dilution. See, generally,

423 F. Supp. at 394-399. Alternatively, the court found racial

motivation in the perpetuation of the at-large commission system

to have been adequately demonstrated, id. at 391.

- 29 -

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

i :

100/

These cases resent. for the first time in this Circuit

the question of the validity of the use of the commission

form of municipal government in circumstances where other

at-large systems of representation would unconstitutionally

dilute the black vote. The violation here is not the fusion

of legislative and executive functions, but the maintenance

of a system which deprives blacks of an equal chance for

legislative representation on the commission. The rationale

of the decisions below does not foreclose cities such as

Mobile and Shreveport from maintaining some of the attributes of

a commission system of government, so long as blacks are

not effectively frozen oul of the legislative body. Since

no such system has been proposed by the defendants here, these

are not appropriate cases in which to explore the possibility

of adapting commission government so as to eliminate dilution.

It is, however, important to leave open that possibility, to

be considered in other cases, in the remedy proceedings in the

Shreveport case, or in evaluating any future Mobile plan. The

remedy must be directed at eliminating unlawful dilution,

not at eliminating commission government.

100/ The Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit has held

that a state's interest in maintaining the commission form

of government does not justify otherwise unconstitutional

dilution of the black vote. Kendrick v. Walder, 527 F.2d

44 (Ith Cir. 1975).

-30-

II

In our view, the decisions of the courts below should be

affirmed. Both courts properly interpreted the principles of

White v. Regester, supra, and correctly applied those principles

to the facts before them.

: The district Sours found: that blacks lacked effective

access to Shreveport's and Mobile's political processes;

that blacks in both cities suffered from the effects of

extensive official racial discrimination; that officials

in both cities were unresponsive to the interests of blacks

in employment and other areas; and that the cities' majority-

vote requirements, “place” requirements, rand the lack of |

residency requirements (other than city residency) had

the effect of minimizing black voting ESOT. These findings

are supported by substantial evidence and are not clearly

erroneous. Therefore they may not be set aside on appeal.

Rule 52{x), FP. Re. Civ. Pu.

The findings of the district courts are sufficient

to establish violations of the Equal Protection Clause of the

Four teenth Amendment, as interpreted by the Supreme Court in

White v. Regester, and of the Fifteenth Amendment. The facts

of these cases are closely analogous to the facts of White

Vv. Regester, in which the Court held unconstitutional multi-

member district plans for Dallas and Bexar Counties, Texas,

and are different from the facts of Whitcomb v. Chavis, supra,

| m3 Lm

in wich the Court upheld the use of a multi-member district

for Marion County, Indiana. Moreover, the facts of the

instant cases are similar to those of several other cases

in which this Court has held that at-large or multi-member

district voting schemes unconstitutionally dilute minority

voting strength. The district courts did not base their de-

elsions on the mistaken notion that racial minorities have a

right to proportional representation. Rather, the constitutional

violation lies in maintaining a form of representation which

perpetuates the effects of past official racial discrimination

and which maximizes the adverse impact of private racial bias.

Because the conclusions of the district courts represent "a

blend of history and an intensely local appraisal of the de-

sign and impact" of the at-large plans in question, they are

’s

entitled to special deference frcm this Court. White, supra,

412 U.S. at 769-7740.

111

The district courts were correct in not requiring

plaintiffs to demonstrate that the voting plans in

question were adopted with an intent or purpose to

discriminate against blacks. The test is whether

“designedly or otherwise" an at-large or multi-member

plan operates to minimize or cancel out minority

=32-

|

voting strength. In .neither White v. Regester nor Whitcomb v.

Chavis aid tne cupreme Court say that the Equal Protection

rs-wce Of the Fourteenth Amendment resuires proof of official

racial intent in cases such as these. Neither Washington v.

Davis, supra, nor Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development. Corp., 45 U0.S.L.W. 4073 (U.S. Jan. 11, 1977),

dealt with at-large or multi-member district plans. Neither

case made any reference to White v. Regester, Whitcomb v.

Chavis, or any lower court decision dealing with such

voting plans. In these circumstances, Washington v. Davis

and Arlington Heights cannot properly be interpreted as

overruling or modifying the White and Whitcomb criteria.

. In several decisions rendered after Washington v. Davis

and Arlington Heights, this Court has ruled that the,

White standards, as interpreted and applied by the Court

in Zimmer v. McKeithen, supra, still govern in this

Circuit,

| Even if the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment does require proof of racial intent in the enactment

of an at-large or multi-member district plan, the Fifteenth

Amendment does not. Washington v. Davis and Arlington Heights

. apply only to violations of the Equal Protection Clause, and

the Supreme Court has never held that proof of racial effect

“33

ir

is insufficient to establish a Fifteenth Amendment violation.

That proof of official racial purpose is not required under

the Fifteenth Amendment is supported by Congress's determination,

in enacting Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, that it can

implement the Fifteenth Amendment by proscribing laws which have

the effect of ony lng or abridging the right to vote on account

of race, regardless of the purpose or sotive behind such laws.

Even if proof of racial purpose is required by both

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, such purpose may

be inferred from the facts of both the instant cases. Direct

evidence of racial purpose is not required; rather, racial

purpose may be shown by circumstantial evicence. forsover , such

purpose need not be present in the enactment of the voting

plan under review. Findings of cur posstul maintenance of the

discriminatory scheme - such as those made in both the instant

cases - are sufficient to establish the‘requisite discriminatory

purpose. When plaintiffs establish - as they did in the instant

cases - the White v. Regester factors of past discrimination,

racially polarized voting, and the present unresponsiveness

of elected officials, they have made a sufficient showing

of invidious racial purpose under the criteria of Washington

v. Davis and Arlington Heights, supra. An at-large voting

‘plan, itself racially neutral, is unconstitutional if it

carries forward intentional and purposeful discriminatory denial

of access to the political process.

asa

IV

~ The orders of the district SOUL LY 2s to relief

were! vell within the courts' broad remedial powers.

The structure of the cities' governments is not inmone

from federal judicial review and must give way to the re-

quirements of -the Constitution. In Mobile, the district

court was forced to design an interim plan after the defend-

ants failed to respond to the opportunity to submit their

own proposals. In Shreveport, the precise contours of. the

remedy have not yet been established. The cities' attacks

upon the relief granted by the courts below, essentially

pleas that no relief at all should have been granted, are

without merit.

- 35 =

ARGUMENT

I

THE DISTRICT COURTS CORRECTLY HELD THAT THE AT-LARGE

SCHEMES FOR ELECTING CITY COMMISSIONERS IN SHREVEPORT

AND MOBILE IMPERMISSIBLY DILUTE BLACK VOTING STRENGTH

IN THOSE CITIES

A. The courts below correctly applied the principles

of White v. Regester. 32

White v. Regester teaches that at-large or multi-member

district voting plans are not per se unconstitutional. Such

plans, however, may violate the Constitution, if they "are

being used invidiously to cancel out or minimize the voting

strength of racial groups,” 412 U.S. at 765. "The plaintiffs’

burden is to produce evidence to support findings that the politi-

cal processes leading to nomination and election were not equally

open to participation Be the group. in question ~-- that its members

had less opportunity than did other residents in the district to

participate in the political processes and to elect legislators

of their choice." White v. Regester, supra, 412 U.S. at 766,

citing Whitcomb v. Chavis, supra, 403 U.S. at 149-150.

To determine whether an at-large or multi-member

district voting plan unconstitutionally dilutes minority

voting strength, a court must consider a number of factors.

Compare White v. Regester with Whitcomb v. Chavis. This

Circuit, en banc, discussed these factors in Zimmer v.

McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (1973), affirmed on othér grounds

sub nom. East Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424

“36-

: 101/

U.8. 636 (1976). The Court stated:

The Supreme Court has identified a panoply

of factors, any number of which may contribute to

the existence of dilution. Clearly, it is not

enough to prove a mere disparity between the

number of minority residents and the number of

minority representatives. Where it is apparent

that a minority is afforded the opportunity to

participate in the slating of candidates to

"represent its area, that the representatives

slated and elected provide representation respon-

sive to minority's needs, and that the use of a multi-

member districting scheme is rooted in a strong state

policy divorced from the maintenance of racial

discrimination, Whitcomb v. Chavis, suora, would

require a holding of no dilution. Whitcomb would

not be controlling, however, where

the state policy favoring multi-member

or at-large districting schemes is rooted

in racial discrimination. Conversely,

where a minority can demonstrate a lack of

access to the process of slating candidates,

the unresponsiveness of legislators to their

particularized interests, a tenuous state

policy underlying the preference for multi-

member or at-large districting, or that the

existence of past discrimination in general

precludes the effective participation in

the election system, a strong case is made. - ,

Such proof is enhanced by a showing of

the existence of large districts, majority

vote requirements, anti-single shot voting

provisions and the lack of provision for .at-

101/ The district court in the East Carroll litigation adopted

a reapportionment plan calling for the at-large election

of members of both the police jury and the school board of

East Carroll Parish, Louisiana. In Zimmer, this Court

reversed, finding clearly erroneous the district court's

ruling that at-large elections would not dilute black

voting strength in the parish. The Supreme Court affirmed,

“but without approval of the constitutional views exvressed

by [this Court] ," 424 U.S. at 638. The Supreme Court ruled

that the district court had erred under Connor v. Johnson,

402 U.S. 690 (1971), in endorsing a multi-member plan.

Connor requires federal district courts to give preference

to single-member districts when devising reapportionment

plans to replace invalid state legislation. Since the

Supreme Court did not reach the constitutional issue, its

affirmance in East Carroll indicates neither approval

nor disapproval of the constitutional views expressed by

this Court in Zimmer.

| 57

ir

large candidates running from particular -

geographical subdistricts. The fact of

dilution is established upon proof of the

existence of an aggregate of these factors.

The Supreme Court's recent pronouncement in

White v. Regester, supra, demonstrates, however,

“that all theses factors need not be proved in

order to obtain relief. (485 F.24 at 1305;

footnotes omitted.)

This Court reiterated these principles in Wallace Vv.

102/

House, supra, 515 F.2d at 623. See also Kirksey

v. Supervisors of Hinds County, Mississippi, No. 75-2212,

(5th Cir., decided May 31, 1977) (en banc). In our view,

"this language is a correct explanation of the principles

of White v. Regester and Whitcomb v. Chavis.

102/ In Wallace, the district court held that the at-large

scheme for the election of the five aldermen in Ferriday,

Louisiana, unconstitutionally diluted black voting power.

. It ordered the implementation of a plan calling for the

election of the aldermen from single-member districts.

This Court reversed, holding that the lower court should

have ordered the implementation of a plan proposed by the

city providing for the at-large election of one of the

five aldermen. The Supreme Court vacated this Court's

judgment and remanded the case "for further consideration

in light of East Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall ..."

(see note 101, supra). Thus in Wallace the Supreme Court

took issue with the form of relief sanctioned by this

Court, not with the constitutional principles it had

articulated. See Wallace v. House, 538 P.24 1138 (5th Cir.

1976). In cases decided after the Supreme Court's actions

in East Carroll and Wallace, this Court has held that the

constitutional principles of Zimmer still apply in this

Circuit. See Paige v. Gray, supra, 538. P.24 at 1110-1111 n. 4;

McGill v. Gadsden County Commission, 535 F.2d 277, 280 (1976);

Nevett v. Sides, »33 F.<a 1361, 1364 (1976). ‘This panel, there-

fore, is bound by the en banc decision in Zimmer. Cf. Vandenades

v. United States, 523 F.2d 1720, 1223 {3th Cir. 1975); Atlantis

Develooment corp. v. United States, 379 F.24 818, 828 (5th Cir.

1967).

«33.»

With due regard for those standards, the district

courts found that blacks lacked effective access to

Shreveport's and Mobile's political processes; that

blacks had long suffered from, and continued to suffer

from, the effects of extensive official racial discrimina-

tion The courts also found that the city officials in

Shreveport were unresponsive to the interests of blacks,

particularly in the areas of housing and employment, and Ehak

in Mobile, the city commissioners had been unresponsive to

black interests in employment, appointments to boards and

desegregation of public facilities. The Bolden court further

found that the Mobile city commissioners' “sluggish and timid"

(423 F. ‘Supp. at 392) response to racial incidents in 1976

demonstrated the “low priority given to the needs of black

citizens..." (ibid.). In addition, both courts found that the

cities’ majority-vote requirements (majority primary, in

Shreveport), "place" requirements, and lack of residency

requirements for candidates for city commissioner operated to

103/ The district court in B.U.L.L. did not cite any statistics

In support of its statement that black voter registration per-

centages remain lower than registration percentages for whites,

and the record does not appear to contain such statistics.

However, proportionately lower black voter registration is less

significant in a case such as this, where blacks constitute a

minority of the population, than in a case such as Zimmer v.

McKeithen, supra, where blacks constituted a majority of the

population, but a minority of the registered voters. Where

‘blacks constitute a distinct population minority, it is unlikely,

given racial bloc voting and an at-large system, that they will

be able to play a decisive role in any election even if the

percentage of blacks who are registered voters equals the

. white percentage.

- 30

submerge black voting strength. Those findings are

sufficient, in both cases, to sSeppont the con-

clusion that the at-large schemes «in Shreveport and Mobile

were "formulated in the context of an existent intentional

denial of 53688 by minority group members to the political

process, and ... perpetuate that denial." Kirksey v.

Board of Suvervisors of Hinds County, supra, slip. op. p. 9.

The facts found by the district courts in these

cases are more closely analogous to the facts of White v.

Regester than to those of Whitcomb v. Chavis. Facts present

in both White and the instant cases include the following:

(1) a history of official racial discrimination; (2) the

unresponsiveness of elected officials to minority interests;

(3) few or no minorities elected to office; (4) a "majority

primary" law, a "place" rule, and the absence of a residency

requirement. By contrast, in Whitcomb black candidates were

- 40 -~

| 104/

regularly slated by both political parties and on several

occasions were elected (403 U.S. at 150-152 n.30). Moreover,

in Whitcomb elected officials were not shown to be unrespon-

sive to black interests (id. at 155), and there was no history

of official racial discrimination. The facts of these cases

are analogous to those of other cases in which this Court has

found that at-large or multi-member voting schemes unconstitu-

tionally dilute minority voting power. See, £.9.. Wallace Ve

House, supra, 515 F.2d at 622-624; Perry v. City of Opelousas,

515 F.24 639, 641 (5th Cir. 1975); Moore v. Leflore County

Board of Election Com'rs, 502 F.2d 621, 624, 627 (5th Cir. 1974);

Turner v. McKeithen, 490 F.2d 191, 193-197 (5th Cir. 1973):

Zimmer v. McKeithen, supra, 485 F.2d at 1304-1307.

104/ In White v. Regester, supra, the Supreme Court appeared

To base its conclusion that blacks in Dallas County,” Texas,

were denied access to the political process in part upon

the finding that blacks were effectively excluded from

participation in the Democratic Party primary selection

process for that County. 412 U.S. at 766-767. In neither

Shreveport nor Mobile is there a candidate slating process

like that in Dallas County. The absence of a candidate

slating process in the instant cases is not determinative,

however. In holding that Mexican-Americans were excluded

from the political process in Bexar County, Texas, the

Court in White v. Regester made no reference to any

candidate slating process in that county. 412 U.S. at

767-770. Exclusion from a candidate slating process is

therefore not an. essential element. It makes no difference

at which stage of the political process blacks are

excluded. The practical effect is the same, whether they

are denied effective participation in orimary or general

elections. This is particularly true in Mobile, where, as

the district court found, black support for a candidate

could have a negative impact on the candidate's chances

to be elected. 423 F. Supp. at 388, and see p. 44, infra.

- 4] -

With the possible exception of Mobile's brief, pp. 35-43

(addressed in part “B" of this section), the appellants do

nos expressly challenge the district court's factual findings

as clearly erroneous. 10% not clearly cerroneous, they may

not be set aside on appeal, Rule 52(a), Fed. R. Civ. P. The

district courts' conclusions, based upon these findings, are

entitled to deference, "representing as [they do] a blend of

history and ... intensely local appraisal/(s] of the design [s]

and impacts] of [at-large voting in Mobile and Shreveport]

in light of past and present realit[ies], political and

. otherwise.” White v. Regester, supra, 412 U.S. at 769-770.

B. The Mobile court correctly found blacks were

excluded from the political process.

Though it is undisputed that no black candidate has

ever won an at-large election in Mobile, appellants claim that

the district court's ultimate finding of exclusion from the

106/

political process is in error, Brief for Appellants, pp. 1,

105/ Shreveport's discussion of the evidence, Brief, pp. 32-45,

fails to demonstrate that any of the district court's findings are

plainly wrong. Rather, the soundness of the court's factual findings

is illustrated by the discussion at pp. 5-13 of the Shreveport

plaintiffs-appellees' brief.

106/ Since the Mobile appellants take issue with the district

court's ultimate finding, necessarily a combination of fact

and law, the "clearly erroneous" rule probably is inapplicable

here.

- a3

35-43. The basis for this claim ABpasis to be: (1) blacks

have voted in Mobile, particularly ‘since 1965; (2) most

candidates solicit the endorsement:of the Non-partisan Voting

League; and, (3) some candidates for whom some blacks vote

sometimes win. In so arguing, the Mobile appellants fail to

credit the impact of racially polarized-voting when it is

combined with at-large, numbered place elections. |

In Graves v. Barnes, 343 F. Supp. 704, 719, (W.D.

Tex. 1972), aff'd. sub nom. White v. Regester, supra, the

court said:

The underpinning of the apportionment cases is

the Fourteenth Amendment right to an effective

vote within the general constructs of what 1s

essentially a majoritarian system of representa-

tive government [citations omitted; emphasis

added].

Racially polarized voting, by itself, does not necessarily

deprive minorities of fair representation. As the Supreme

Court noted in United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh,

Inc. v. Carey, 45 U.S.L.W. 4221, 4227 (U.S. Mar. 1, 1377),

when fair and neutral single-member districts are drawn,

a racial minority may lose in any given district, but

the overall system of representation will generally reflect

fairly the approximate voting strength of majorities and

minorities. Thus, so long as whites controlled a majority of

Brooklyn's legislative districts, whites could not be heard to

complain that they were a minority in the district encompassing

Williamsburgh. Where, as in Mobile, the electoral system,

y implements and encourages racially polarized voting, and sub-

-43-

merges a racial minority in a ‘manner that renders its votes

impotent, the system is, in effect, "state action"

effectuating a racial classification. Cf. Anderson v.

Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964). Where there is a history of

racial discrimination and unresponsiveness to black interests

as well as polarized voting, a court may well make the prog-

nosis that the at-large system will perpetuate this adverse im-

pact upon the racial-minority voter. Cf. Kirksey v. Board

of Supervisors of Hinds County, Mississippi, supra.

It should be stressed that this is not a political context

in which there is occasionally an issue upon which voters

divide along racial lines, or a coincidence of black and

working class voting, e.g., Whitcomb v. Chavis, supra. The

White-Zimmer formula is pre-eminently applicable to the sit-

uation in Mobile in which race has demonstrably been, and retains

’

the potential for being, the single most divisive issue.

One indication that this is so is the failure of blacks to

be elected in any city-wide or county-wide election. As the

Graves court said, 343 F. Supp. at 732:

It is not suggested that minorities have a

constitutional right to elect candidates of

their own race, but elections in which minority

candidates have run often provide the best evi-

dence to determine whether votes are cast on

racial lines. All these factors 107/ confirm

the fact that race is still an important issue

in Bexar county and that because of it, Mexican-

Americans are frozen into permanent political

minorities destined for constant defeat at the

hands of the controlling political majorities.

The Mobile appellants' reliance upon the Langan elections

(Brief, p. 42) to show black participation in the political process

107/ The reference is to the preceding pages, 343 F. Supp. at

127-1732.

- 44 - |

is misplaced. The evidence showed, and the district court

found, that Langan's white support diminished as his

black suppor t increased. Indeed, expert testimony tended

to show that black impact on the results of elections

declined in direct proportion to their increase in regis-

tration and turnout because the heavier the black vote, the

greater the "backlash," i.e, the polarization. Nor is this

a matter of mere statistical correlation. The campaign

literature in Langan's 1969 and 1972 campaigns (see pp. 20, 22-23,

supra) demonstrated that nis opposition intended to stimulate

and encourage polarization along racial Lines.

To be sure, there are pitfalls in attempting 0 analyze

the election returns, where both racial and non-racial factors

may be present. But the Mobile appellants have not shown that the