McCleskey v. Kemp Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and Brief Amici Curiae in Support of the Petition for Certiorari

Public Court Documents

June 28, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McCleskey v. Kemp Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and Brief Amici Curiae in Support of the Petition for Certiorari, 1985. dd42366c-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/09bd267c-7b9e-4970-a09f-41177957ea3c/mccleskey-v-kemp-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amici-curiae-and-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-the-petition-for-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

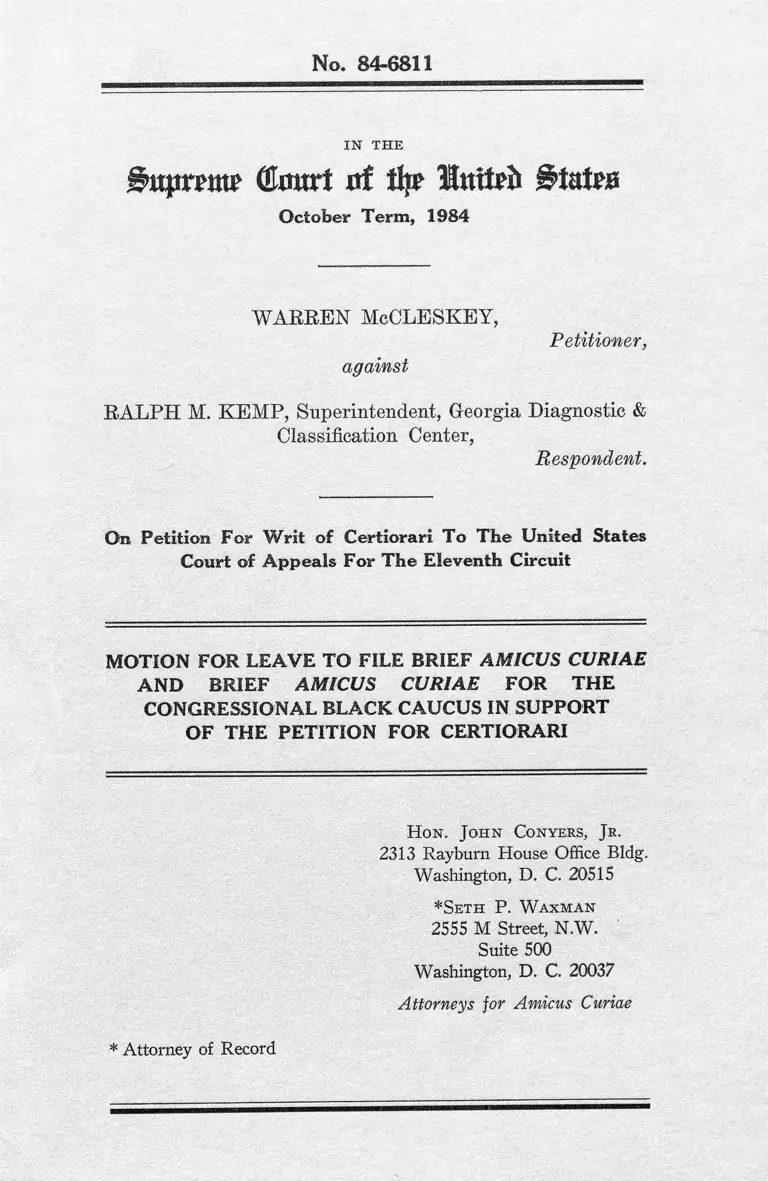

No, 84-6811

IN THE

fflm nrt xxt % M ntteb S ta te #

October Term, 1984

WARREN McCLESKEY,

against

Petitioner,

RALPH M. KEMP, Superintendent, Georgia Diagnostic &

Classification Center,

Respondent.

On Petition For Writ of Certiorari To The United States

Court of Appeals For The Eleventh Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

AND BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE FOR THE

CONGRESSIONAL BLACK CAUCUS IN SUPPORT

OF THE PETITION FOR CERTIORARI

Hon. John Conyers, Jr.

2313 Rayburn House Office Bldg.

Washington, D. C. 20515

*Seth P. W axman

2555 M Street, N.W. '

Suite 500

Washington, D. C. 20037

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

* Attorney of Record

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities .............. ii

Motion For Leave To File

Brief Amicus Curiae .......... iv

Summary of Argument ............... 1

Argument

Neither The Eighth Amendment

Nor The Equal Protection Clause

Of The Fourteenth Amendment

Allow Courts Or Juries Sys

tematically To Punish Black

Defendants, Or Those Whose

Victims Are White, More

Severely For Similar Crimes

Than White Defendants, Or

Those Victims Are Blacks .... 3

Conclusion .................. ...... 10

l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559

(1953) ....................... 7

Briscoe v. LaHue, 460 U.S. 325

(1983) ....................... 6

Carter v. Texas, 177 U.S. 442

(1900) ....................... 6

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482

(1977) ....................... 9

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238

(1972) 6

General Building Contractors

Ass'n, Inc. v. Pennsylvania,

458 U.S. 375 ( 1982) 5

Hazelwood School District v.

United States, 433 U.S. 299

(1977) 9

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1

(1967) ....................... 6

McCleskey v. Kemp, 753 F.2d 877

(11th Cir. 1985)(en

banc) ................... vi, vii ,5,8

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587

(1935) ....................... 6

Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545

(1979) 7

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S.

303 ( 1 880) .......................... 6

Page

- ii -

Page

Texas Dep't of Community Affairs

v. Burdine, 450 U.S. 248

( 1981 ) 9

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346

( 1970) .............. 7

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S.

356 ( 1886) ................... 6

Zant v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862

(1983) ....................... viii

- iii -

No. 84-6811

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1984

WARREN McCLESKEY,

Petitioner,

- against -

RALPH M. KEMP, Superintendent,

Georgia Diagnostic & Classification

Center,

Respondent.

On Petition For Writ of Certiorari

To The United States Court of Appeals

For The Eleventh Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO

FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

The Congressional Black Caucus

respectfully moves this Court, pursuant to

IV

Rule 36.1 of its Rules, for leave to file

the attached brief amicus curiae in

support of Warren McCleskey's petition for

certiorari in this case. The consent of

the petitioner has been obtained. Counsel

for respondent, however, has declined our

request for consent, necessitating this

motion.

The Congressional Black Caucus ("the

Caucus") is composed of all 20 black

members of the United States House of

Representatives. The primary function of

the Caucus is to implement and preserve

the constitutional guarantee of equal

justice under the law for all Americans,

particularly black Americans.

v

The Caucus requests leave to file a

brief amicus curiae to make plain the

troubling constitutional implications it

finds in the opinion of the Court of

Appeals, and the consequent importance to

black citizens of the issues raised by the

McCleskey v. Kemp case.

Warren McCleskey has presented

substantial evidence that racial discrimi

nation is at work in the capital punish

ment statutes of the State of Georgia. His

claims, based primarily on the comprehen

sive studies of Professor David Baldus,

are well-documented, and the State's

contrary evidence appears insubstantial

and unpersuasive.

We come before this Court, however,

not to debate the merits of McCleskey's

evidence, for the Court of Appeals itself

did not decide against McCleskey by

dismissing his factual case. Instead, it

vi

explicitly accepted, for purposes of the

appeal, the validity of the Baldus study,

and assumed that McCleskey v. Kemp, 753

F.2d 877, 886 (11th Cir. 1985)(en banc)

"proves what it claims to prove." Id.

Even so, the Court of Appeals reasoned

that petitioner has stated no claim under

the Eighth or Fourteenth Amendments.

It is this extraordinary constitu

tional ruling that prompts our interven

tion as amicus curiae. Even while

acknowledging substantial disparities by

race in Georgia's death sentencing rates

— • approaching twenty percentage points in

the midrange of homicide cases — and an

overall average racial disparity exceeding

six percentage points, the Court of

Appeals holds that Eighth and Fourteenth

Amendments are unaffected.

If this troubling opinion goes unre

viewed, fundamental constitutional issues

V l l

long ago settled in this nation will once

again be open to serious question. It is

cause enough for grave concern if the

pattern of executions now being carried

out in this country is infected by racial

discrimination. Yet if a federal court

may announce that such discrimination

makes no legal difference, if it holds

that such a pattern affronts no constitu

tional principles, the time has come, the

Caucus believes, for this Court to be

heard.

As the ultimate guardian of our

constitutional values, this Court cannot

afford to overlook a pronouncement, by a

majority of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit sitting

en banc, that appears to condone some

measure of racial discrimination in

capital sentencing. This Court has noted

that "Georgia may not attach the 'aggra-

- viii -

vating' label to factors that are consti

tutionally impermissible or totally

irrelevant to the sentencing process, such

as ... race." Zant v. Stephens (II) 462

U.S. 862 , 885 ( 1983). Yet the McCleskey

opinion threatens to give _de facto

sanction to just such a practice. The

Caucus, one of whose principal aims is to

ensure that equal justice under law

remains a reality for all citizens,

respectfully requests leave to file this

brief amicus amicus to address these

important issues.

Dated: June 28, 1985

Respectfully submitted,

HON. JOHN CONYERS, JR.

2313 Rayburn House Office Bldg.

Washington, D.C. 20515

*SETH P. WAXMAN

2555 M Street, N.W.

Suite 500

Washington, D.C. 20037

ATTORNEYS FOR AMICUS CURIAE

B y __________ ________________ _

*Attorney of Record

- IX

No. 84-6811

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1984

WARREN McCLESKEY,

Petitioner,

- against -

RALPH M. KEMP, Superintendent,

Georgia Diagnostic & Classification

Center,

Respondent.

On Petition For Writ of Certiorari

To The United States Court of Appeals

For The Eleventh Circuit

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE

BLACK LEGISLATIVE CAUCUS

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Court of Appeals, for purpose of

Warren McCleskey's appeal, has accepted

the validity of his statistical evidence

2

demonstrating (i) that black defendants,

or those whose victims are white, are

substantially more likely to receive death

sentences in the State of Georgia than are

white defendants, or those whose victims

are black; and (ii) that these record

disparities are not explained by any of

over 230 other legitimate sentencing

factors. Despite this overwhelming proof

that race plays a part Georgia's capital

sentencing system, the Court of Appeals

had held that neither the Eighth nor the

Fourteenth Amendments are implicated,

apparently because it finds the magnitude

of the racial influence to be relatively

minor. Viewed as a statement of legal

principle, this opinion by the Court of

Appeals is astonishing; it turns its back

on a consistent, hundred-year history of

interpretation of the Equal Protection

Clause. Viewed as a statement of fact,

the opinion is equally deficient. It

3

misunderstands the true magnitude and

importance of the statistical results

reported in the Baldus studies. Under any

analysis, the opinion deserves review by

this Court.

ARGUMENT

NEITHER THE EIGHTH AMENDMENT NOR THE

EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE OF THE FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENT ALLOW COURTS OR JURIES

SYSTEMATICALLY TO PUNISH BLACK DEFEN

DANTS, OR THOSE WHOSE VICTIMS ARE

WHITE, MORE SEVERELY FOR SIMILAR CRIMES

THAN WHITE DEFENDANTS, OR THOSE WHOSE

VICTIMS ARE BLACK

The Baldus studies examine the dis

position by Georgia's criminal justice

system of a wide range of homicides

committed over a seven-year period from

1973 through 1979. Baldus and his

colleagues collected data from official

state files on over 500 items of informa

tion for each case, providing a comprehen

sive picture of the crimes, the defen

4

dants, the victims, and the strength of

the State's evidence. After employing a

variety of accepted social scientific

methods to analyze his data -- each of

which the Court of Appeals assumed to be

valid for purposes of McCleskey's appeal

— Baldus reported that "systematic and

substantial disparities exist in the

penalties imposed upon homicide defendants

in the State of Georgia based upon the

race of the homicide victim," (Fed. Hab.

Tr. 726-27) (Professor Baldus), and to a

slightly lesser extent, "upon the race of

the defendant." (Id.) Baldus found no

"legitimate factors not controlled for in

[his] analyses which could plausibly

explain the persistence of these racial

disparities," (Id. 728).

In short, the Baldus studies conclude

that race continues to play a real,

systematic role in determining who will

receive life sentences and who will be

5

executed in the State of Georgia. By

assuming the truth of those conclusions,

the Court of Appeals has sharply focused

the underlying constitutional issue on

this appeal: does proven racial discrimi

nation in capital sentencing violate the

Eighth or Fourteenth Amendments. The

astonishing answer of the Court of Appeals

is that it does not.

The Court does take issue with the

Baldus studies on the exact magnitude of

the racial effect — whether it is nearer

six percentage points or twenty points.

See McCleskey v. Kemp, 753 F. 2d 877,

896-98 (11th Cir. 1985)(en banc). That

question, however, seems plainly beside

the point. The Black Caucus has long

understood that unequal enforcement of

criminal statutes based upon racial

considerations violates the Fourteenth

Amendment. Such distinctions, whatever

their magnitude, have "no legitimate

6

overriding purpose independent of invidi

ous racial discrimination ... [justifying]

the classification," Loving v. Virginia,

388 U.S. 1, 11 (1967); Yick Wo v. Hopkins,

118 U.S. 356 (1886); cf. Furman v. Geor

gia, 408 U.S. 238, 389 n.12 (Burger, C.J.,

dissenting).

One of the chief aims of the Equal

Protection Clause was to eliminate of

discrimination against black defendants

and black victims of crime. See General

Building Contractors Ass'n, Inc. v.

Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. 375, 382-91 (1982);

Briscoe v. LaHue, 460 U.S. 325, 337-40

(1983). Indeed, for well over 100 years,

this Court has consistently interpreted

the Equal Protection Clause to prohibit

racial discrimination in the administra

tion of the criminal justice system. See,

e.g., Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S.

303 (1880); Carter v. Texas, 177 U.S. 442

(1900); Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559( 1 935 ) ;

( 1 9 5 3 ); Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346

( 1 970 ); Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545

(1979). While questions concerning the

necessary quantum of proof have occasion

ally proven perplexing, no federal court

until now has ever, to our knowledge,

seriously suggested that racial discrimi

nation at any level of magnitude, if

clearly proven, can be constitutionally

tolerated. Yet that is precisely the

holding of the Court of Appeals.

Moreover, even if the magnitude of

discrimination were a relevant constitu

tional consideration, Warren McCleskey's

evidence has demonstrated an extraordinary

racial effect. The increased likelihood

of a death sentence if the homicide victim

is white, for example, is .06, or six

percentage points, holding all other

factors constant. Since the average

death-sentence rate among Georgia cases is

8

only .05, the fact that a homicide victim

is white, rather than black, increases the

average likelihood of a death sentence by

120%, from .05 to .11. The suggestion of

the Court of Appeals that race affects at

most a "small percentage of the cases,"

McCleskey v. Kemp, supra, 753 F.2d at 899,

scarcely does justice to these figures.

In plainest terms, these percentages

suggest that, among every 100 homicides

cases in Georgia, 5 would receive a death

sentence if race were not a factor; in

reality, where white victims are involved,

11 out of 100 do. Six defendants are

sentenced to death with no independent

explanation other than the race of their

victims.

Furthermore, the racial disparities

are far more egregious among those cases

where death sentences are most frequently

imposed. Baldus' studies demonstrate

that, among the midrange of cases, the

9 -

race of victim has a .20, or twenty

percentage point impact in addition to

every other factor considered. Such

results simply are intolerable under our

Constitution, especially when the stakes

are life and death.

We are tempted to believe that the

Court of Appeals' opinion reflects, in

part, less a conscious decision to

tolerate racial discrimination than a

sense that the Baldus studies are not

sufficiently reliable. However, accepted

at face value as the Court announces it

has done, the Baldus studies account for

over 230 non-racial variables, and far

exceed any reasonable prima facie standard

of proof ever announced by this Court.

See generally, Texas Dept, of Community

Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. 248 (1981);

Hazelwood School District v. United

States, 433 U.S. 299 (1977); Castaneda v.

Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977).

10

The practical effect of the McCleskey

holding, therefore, will be to declare

that capital punishment may be imposed and

carried out throughout the states of the

Eleventh Circuit — Georgia, Florida, and

Alabama — even if race continues to

influence sentencing decisions in those

states. We strongly urge the Court to

grant certiorari to review the opinion of

the Court of Appeals

CONCLUSION

The petition for certiorari should be

granted.

Dated: June 28, 1985

Respectfully submitted,

HON. JOHN CONYERS, JR.

2313 Rayburn House Office Bldg.

Washington, D.C. 20515

*SETH P. WAXMAN

2555 M Street, N.W.

Suite 500

Washington, D, C. 20037

ATTORNEYS FOR AMICUS CURIAE

By: _____

*Attorney of Record

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I am a member of

the bar of this Court, and that I served

the annexed Motion for Leave to File Brief

Amicus Curiae and Brief Amicus Curiae on

the parties by placing copies in the

United States mail, first class mail,

postage prepaid, addressed as follows:

John Charles Boger, Inc.

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

Mary Beth Westmoreland, Esq.

132 State Judicial Bldg.

40 Capitol Square, S.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30334

Martin F. Richman, Esq.

Barrett, Smith, Shapiro

Simon & Armstrong

26 Broadway

New York, New York 10014

Ralph G. Steinhardt, Esq.

Patton, Boggs & Blow

2550 M Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20037

Done this 28 th day of June, 1985.

Attorney for Amicus Curiae

°<SiS°307 BAR Press, Inc., 132 Lafayette St., New York 10013 - 966-3906

(2998)